Entrepreneurship and Intrapreneurship in Social, Sustainable, and Economic Development: Opportunities and Challenges for Future Research

Abstract

1. Introduction

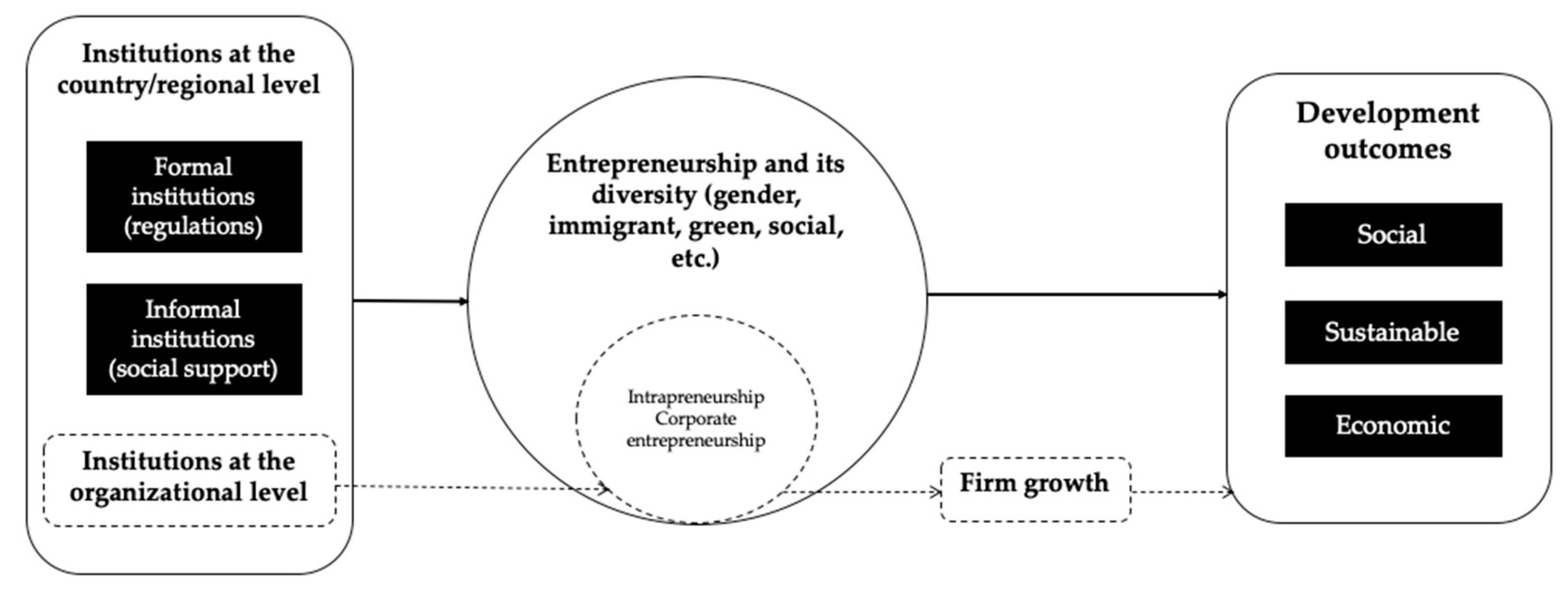

2. Institutional Context for Entrepreneurship and Intrapreneurship

3. Entrepreneurship and Intrapreneurship as Engines of Development

3.1. Social, Sustainable, and Economic Outcomes of Entrepreneurship

3.2. Instrapreneurship as a Source of Social, Sustainable, and Economic Change

4. Summary of the Papers in the Special Issue

5. Conclusions and Ways Forward

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- McMullen, J.S. Delineating the domain of development entrepreneurship: A market–based approach to facilitating inclusive economic growth. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2011, 35, 185–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aparicio, S.; Audretsch, D.; Urbano, D. Does entrepreneurship matter for inclusive growth? The role of social progress orientation. Entrep. Res. J. 2020, in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landström, H.; Harirchi, G.; Åström, F. Entrepreneurship: Exploring the knowledge base. Res. Policy 2012, 41, 1154–1181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bjørnskov, C.; Foss, N.J. Institutions, entrepreneurship, and economic growth: What do we know and what do we still need to know? Acad. Manag. Perspect. 2016, 30, 292–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acs, Z.J.; Boardman, M.C.; McNeely, C.L. The social value of productive entrepreneurship. Small Bus. Econ. 2013, 40, 785–796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, T.A.; Shepherd, D.A. Building resilience or providing sustenance: Different paths of emergent ventures in the aftermath of the Haiti earthquake. Acad. Manag. J. 2016, 59, 2069–2102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urbano, D.; Aparicio, S.; Audretsch, D. Twenty-five years of research on institutions, entrepreneurship, and economic growth: What has been learned? Small Bus. Econ. 2019, 53, 21–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Audretsch, D.B.; Kuratko, D.F.; Link, A.N. Making sense of the elusive paradigm of entrepreneurship. Small Bus. Econo. 2015, 45, 703–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noguera, M.; Alvarez, C.; Urbano, D. Socio-cultural factors and female entrepreneurship. Int. Entrep. Manag. J. 2015, 9, 183–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turró, A.; Urbano, D.; Peris-Ortiz, M. Culture and innovation: The moderating effect of cultural values on corporate entrepreneurship. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2014, 88, 360–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pacheco, D.F.; Dean, T.J.; Payne, D.S. Escaping the green prison: Entrepreneurship and the creation of opportunities for sustainable development. J. Bus. Ventur. 2010, 25, 464–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- North, D.C. Institutions, Institutional Change and Economic Performance; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Yunis, M.S.; Hashim, H.; Anderson, A.R. Enablers and Constraints of Female Entrepreneurship in Khyber Pukhtunkhawa, Pakistan: Institutional and Feminist Perspectives. Sustainability 2019, 11, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- North, D.C.; Thomas, R.P. The Rise of the Western World: A New Economic History; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1973. [Google Scholar]

- North, D.C. Understanding the Process of Economic Change; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Williamson, O.E. The new institutional economics: Taking stock, looking ahead. J. Econ. Lit. 2000, 38, 595–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruton, G.D.; Ahlstrom, D.; Li, H.-L. Institutional theory and entrepreneurship: Where are we now and where do we need to move in the future? Entrep. Theory Pract. 2010, 34, 421–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gnyawali, D.R.; Fogel, D.S. Environments for entrepreneurship development: Key dimensions and research implications. Entrep. Theory Pract. 1994, 18, 43–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shane, S. Reflections on the 2010 AMR decade award: Delivering on the promise of entrepreneurship as a field of research. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2012, 37, 10–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmutzler, J.; Andonova, V.; Diaz-Serrano, L. How context shapes entrepreneurial self-efficacy as a driver of entrepreneurial intentions: A multilevel approach. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2019, 43, 880–920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aparicio, S.; Urbano, D.; Stenholm, P. Institutions in Attracting the Entrepreneurial Potential: A Multilevel Approach. Acad. Manag. Proc. 2019, 1, 15408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krueger, N.F., Jr.; Brazeal, D.V. Entrepreneurial potential and potential entrepreneurs. Entrep. Theory Pract. 1994, 18, 91–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thornton, P.H.; Ribeiro-Soriano, D.; Urbano, D. Socio-Cultural Factors and Entrepreneurial Activity. Int. Small Bus. J. 2011, 29, 105–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Welter, F.; Baker, T.; Audretsch, D.B.; Gartner, W.B. Everyday entrepreneurship—A call for entrepreneurship research to embrace entrepreneurial diversity. Entrepr. Theory Pract. 2017, 41, 311–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brush, C.; Edelman, L.F.; Manolova, T.; Welter, F. A gendered look at entrepreneurship ecosystems. Small Bus. Econ. 2019, 53, 393–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alwakid, W.; Aparicio, S.; Urbano, D. Cultural Antecedents of Green Entrepreneurship in Saudi Arabia: An Institutional Approach. Sustainability 2020, 12, 3673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Honig, B. Exploring the intersection of transnational, ethnic, and migration entrepreneurship. J Ethn. Migr. Stud. 2020, 46, 1974–1990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Escamilla-Fajardo, P.; Núñez-Pomar, J.M.; Ratten, V.; Crespo, J. Entrepreneurship and Innovation in Soccer: Web of Science Bibliometric Analysis. Sustainability 2020, 12, 4499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turro, A.; Noguera, M.; Urbano, D. Antecedents of entrepreneurial employee activity: Does gender play a role? Int. J. Entrep. Behav. Res. 2020, in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The New Institutionalism in Organizational Analysis; DiMaggio, P.J., Powell, W.W., Eds.; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 1991; Volume 17. [Google Scholar]

- Bjørnskov, C.; Foss, N.J. Well-being and entrepreneurship: Using establishment size to identify treatment effects and transmission mechanisms. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0226008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urbano, D.; Aparicio, S.; Audretsch, D.B. Institutions, Entrepreneurship, and Economic Performance; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Bruton, G.D.; Ketchen Jr, D.J.; Ireland, R.D. Entrepreneurship as a solution to poverty. J. Bus. Ventur. 2013, 28, 683–689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suddaby, R.; Bruton, G.D.; Walsh, J.P. What we talk about when we talk about inequality: An introduction to the Journal of Management Studies special issue. J. Manag. Stud. 2018, 55, 381–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hechavarria, D.; Bullough, A.; Brush, C.; Edelman, L. High-growth women’s entrepreneurship: Fueling social and economic development. J. Small Bus. Manag. 2019, 57, 5–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smallbone, D.; Dabic, M.; Kalantaridis, C. Migration, entrepreneurship and economic development. Entrep. Reg. Dev. 2017, 29, 567–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz-Rosa, I.; Gutiérrez-Taño, D.; García-Rodríguez, F.J. Social Entrepreneurial Intention and the Impact of COVID-19 Pandemic: A Structural Model. Sustainability 2020, 12, 6970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wigger, K.A.; Shepherd, D.A. We’re all in the Same Boat: A Collective Model of Preserving and Accessing Nature-Based Opportunities. Entrep. Theory Prac. 2020, 44, 587–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holliday, J.; Hennebry, J.; Gammage, S. Achieving the sustainable development goals: Surfacing the role for a gender analytic of migration. J. Ethn. Migr. Stud. 2019, 45, 2551–2565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, J.K.; Daneke, G.A.; Lenox, M.J. Sustainable development and entrepreneurship: Past contributions and future directions. J. Bus. Ventur. 2010, 25, 439–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krause, R.; Wu, Z.; Bruton, G.D.; Carter, S.M. The coercive isomorphism ripple effect: An investigation of nonprofit interlocks on corporate boards. Acad. Manag. J. 2019, 62, 283–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Audretsch, D.B.; Lehmann, E.E.; Menter, M.; Wirsching, K. Intrapreneurship and absorptive capacities: The dynamic effect of labor mobility. Technovation 2020, in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urbano, D.; Turro, A.; Aparicio, S. Innovation through R&D activities in the European context: Antecedents and consequences. J. Technol. Transf. 2020, 45, 1481–1504. [Google Scholar]

- De Falco, S.E.; Renzi, A. Benefit Corporations and Corporate Social Intrapreneurship. Entrep. Res. J. 2020, 10, 20200382. [Google Scholar]

- Klofsten, M.; Urbano, D.; Heaton, S. Managing intrapreneurial capabilities: An overview. Technovation 2020, in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parris, D.L.; McInnis-Bowers, C. Business not as usual: Developing socially conscious entrepreneurs and intrapreneurs. J. Manag. Edu. 2017, 41, 687–726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Honig, B.; Samuelsson, M. Business planning by intrapreneurs and entrepreneurs under environmental uncertainty and institutional pressure. Technovation 2020, in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patriotta, G.; Siegel, D. The Context of Entrepreneurship. J. Manag. Stud. 2019, 56, 1194–1196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Provasnek, A.K.; Schmid, E.; Geissler, B.; Steiner, G. Sustainable corporate entrepreneurship: Performance and strategies toward innovation. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2017, 26, 521–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-González, J.A.; Kobylinska, U.; García-Rodríguez, F.J.; Nazarko, L. Antecedents of Entrepreneurial Intention among Young People: Model and Regional Evidence. Sustainability 2019, 11, 6993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, E.; Lee, Y. College Students’ Entrepreneurial Mindset: Educational Experiences Override Gender and Major. Sustainability 2020, 12, 8272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Georgescu, M.-A.; Herman, E. The Impact of the Family Background on Students’ Entrepreneurial Intentions: An Empirical Analysis. Sustainability 2020, 12, 4775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Litsardopoulos, N.; Saridakis, G.; Hand, C. The Effects of Rural and Urban Areas on Time Allocated to Self-Employment: Differences between Men and Women. Sustainability 2020, 12, 7049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butkouskaya, V.; Llonch-Andreu, J.; Alarcón-del-Amo, M.-D.-C. Entrepreneurial Orientation (EO), Integrated Marketing Communications (IMC), and Performance in Small and Medium-Sized Enterprises (SMEs): Gender Gap and Inter-Country Context. Sustainability 2020, 12, 7159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seikkula-Leino, J.; Salomaa, M. Entrepreneurial Competencies and Organisational Change—Assessing Entrepreneurial Staff Competencies within Higher Education Institutions. Sustainability 2020, 12, 7323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pei, X.-L.; Wu, T.-J.; Guo, J.-N.; Hu, J.-Q. Relationship between Entrepreneurial Team Characteristics and Venture Performance in China: From the Aspects of Cognition and Behaviors. Sustainability 2020, 12, 377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaramillo-Moreno, B.C.; Sánchez-Cueva, I.P.; Tinizaray-Tituana, D.G.; Narváez, J.C.; Cabanilla-Vásconez, E.A.; Muñoz Torrecillas, M.J.; Cruz Rambaud, S. Diagnosis of Administrative and Financial Processes in Community-Based Tourism Enterprises in Ecuador. Sustainability 2020, 12, 7123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ertac, M.; Tanova, C. Flourishing Women through Sustainable Tourism Entrepreneurship. Sustainability 2020, 12, 5643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butkouskaya, V.; Romagosa, F.; Noguera, M. Obstacles to Sustainable Entrepreneurship amongst Tourism Students: A Gender Comparison. Sustainability 2020, 12, 1812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dobrzanski, P.; Bobowski, S. The Efficiency of R&D Expenditures in ASEAN Countries. Sustainability 2020, 12, 2686. [Google Scholar]

| Category | Activity/Outcome | Authors | Contributions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Institutions and entrepreneurship/Intrapreneurship | Entrepreneurship (Entrepreneurial intentions) | Martínez-González, Kobylinska, García-Rodríguez, and Nazarko [50] | Subjective characteristics (i.e., beliefs, social norms, and values) initiate the chain of effects that influence the action variables (i.e., motivation, self-efficacy, intention). Attitude is the nexus variable between both groups of variables in Spain and Poland. |

| Institutions and entrepreneurship/Intrapreneurship | Entrepreneurship (Entrepreneurial intentions) | Jung and Lee [51] | The results indicate that strict invariance held for either gender or educational experiences, while scalar invariance held between the engineering and non-engineering groups. While the male, engineering, and educational experience groups generally scored higher on both the latent and observed sub-scales of the CS-EMS, the results of the conditional effects of grouping variables indicate that educational experiences mattered most. |

| Institutions and entrepreneurship/Intrapreneurship | Entrepreneurship (Entrepreneurial intentions) | Georgescu and Herman [52] | Results show that students with an entrepreneurial family background, effectiveness of entrepreneurship education, and entrepreneurial personality traits reported a higher entrepreneurial intention than those without such a background. However, entrepreneurial family background negatively moderated the relationship between effectiveness of entrepreneurship education and entrepreneurial intention. |

| Institutions and entrepreneurship/Intrapreneurship | Entrepreneurship (Sport) | Escamilla-Fajardo, Núñez-Pomar, Ratten, and Crespo [28] | Through a bibliometric analysis, four clusters about sport entrepreneurship were identified: (1) football, entrepreneurship and social development, (2) football, innovation and management, (3) football, efficiency and new technology, and (4) football, injuries and innovation in rehabilitation. |

| Institutions and entrepreneurship/Intrapreneurship | Entrepreneurship (Gender) | Litsardopoulos, Saridakis, and Hand [53] | This research advanced knowledge on the existence of complex dynamics between gender and age, which affect the allocation of time to self-employment between rural and urban areas. |

| Institutions and entrepreneurship/Intrapreneurship | Intrapreneurship (Gender) | Butkouskaya, Llonch-Andreu, and Alarcón-del-Amo [54] | There is a positive relationship between entrepreneurial orientation (EO), integrated marketing communications (IMC), and performance among SMEs in Spain and Belarus. However, these connections are significantly stronger in the case of male, rather than female managers in a developed market (Spain). The EO-IMC-performance relations are more intensive when the manager is female. |

| Institutions and entrepreneurship/Intrapreneurship | Intrapreneurship | Seikkula-Leino and Salomaa [55] | Entrepreneurial strategies about entrepreneurial thinking and actions at individual and organizational levels have been explored. Both supervisors and employees evaluate themselves and the organization to be entrepreneurial. Results provide insights for universities aiming to implement an entrepreneurial strategy, stressing psychological factors in the development of entrepreneurial competencies. |

| Institutions and entrepreneurship/Intrapreneurship | Intrapreneurship | Pei, Wu, Guo, and Hu [56] | Entrepreneurial team cognition characteristics and behavior characteristics affect venture performance. Additionally, partial mediating effects of entrepreneurial team behavior characteristics on the relationship between cognition characteristics and venture performance were found. |

| Entrepreneurship/Intrapreneurship and development | Social change | Jaramillo-Moreno et al. [57] | Despite having a certificate from the Ministry of Tourism (MINTUR), the Community-Based Tourism Enterprises have not implemented important administrative and financial processes such as a strategic plan, operational plan, market study, cost analysis, process manual, market plan, initial situation, results status, final status, or financial indicators. |

| Entrepreneurship/Intrapreneurship and development | Social change (Gender) | Ertac and Tanova [58] | When psychological empowerment is high, women ecotourism entrepreneurs in Northern Cyprus with a higher level of growth mindset experience a greater level of flourishing, even in an unfavorable context. |

| Institutions, entrepreneurship, and development | Social entrepreneurial orientation and social change | Ruiz-Rosa, Gutiérrez-Taño, and García-Rodríguez [37] | Findings serve to validate the explanatory model of social entrepreneurial intention from the perspective of the theory of planned behavior. Results also show that social entrepreneurial intention decreases in times of deep socioeconomic crises and high uncertainty, such as that caused by COVID-19. |

| Institutions, entrepreneurship, and development | Sustainable entrepreneurship, gender, and sustainable development | Butkouskaya, Romagosa, and Noguera [59] | Economic factors (both societal and university related), the level of innovation in society, and the students’ self-confidence are barrier for sustainable entrepreneurship amongst university students of tourism. Female students were more conscious of the possible obstacles to new business creation than male students. For example, females considered their lack of entrepreneurial education as more significant than did the males. In addition, the female students tended to need more economic and practical support than male students. |

| Institutions, entrepreneurship, and development | Green entrepreneurship and sustainable development | Alwakid, Aparicio, and Urbano [26] | Cultural characteristics such as environmental actions, environmental consciousness, and temporal orientation, increase the level of green entrepreneurial activity across cities in Saudi Arabia. This study contributes to existing knowledge about (informal) institutions, green entrepreneurship, and sustainable development |

| Entrepreneurship/Intrapreneurship and development | Economic growth | Dobrzanski and Bobowski [60] | Hong Kong and the Philippines are the most efficient regarding research and development (R&D) if efficiency is assessed through constant return to scale (CRS) approach. However, according to the variable return to scale (VRS) approach, Hong Kong, Indonesia, Singapore, and the Philippines are more efficient. The study also confirms that increased spending on innovation is resulting in non-proportional effects. |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Aparicio, S.; Turro, A.; Noguera, M. Entrepreneurship and Intrapreneurship in Social, Sustainable, and Economic Development: Opportunities and Challenges for Future Research. Sustainability 2020, 12, 8958. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12218958

Aparicio S, Turro A, Noguera M. Entrepreneurship and Intrapreneurship in Social, Sustainable, and Economic Development: Opportunities and Challenges for Future Research. Sustainability. 2020; 12(21):8958. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12218958

Chicago/Turabian StyleAparicio, Sebastian, Andreu Turro, and Maria Noguera. 2020. "Entrepreneurship and Intrapreneurship in Social, Sustainable, and Economic Development: Opportunities and Challenges for Future Research" Sustainability 12, no. 21: 8958. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12218958

APA StyleAparicio, S., Turro, A., & Noguera, M. (2020). Entrepreneurship and Intrapreneurship in Social, Sustainable, and Economic Development: Opportunities and Challenges for Future Research. Sustainability, 12(21), 8958. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12218958