1. Introduction

Sustainability describes the ability to maintain various systems and processes—environmentally, socially, and economically—in order to give more consideration to the environment. On the same line, there is the responsibility for the impact that the organization exerts on environment, community and society as a whole, in both business and social terms [

1]. In the quest for a sustainable environment, various professionals should develop interdisciplinary solutions for the problem raised by the jobs, communities and workforces, transformed by technological and economic forces [

2].

Thus, we can see that sustainability is a twofold concept: on one side, the environment should be preserved [

3,

4], but, on the other side, if there are actions that negatively influence it this impact should be assessed and, eventually, bypassed or corrected. An auditor’s role in this matter, as part of being a professional that can offer solutions, is to identify the problems and to express an opinion on them, in order for the companies to act more responsibly.

The sustainable approach of the companies involved in M&As is a matter that concerns both the acquirers and the targets involved. The main focus of research in the area concerns two directions. First, we have the influence of the sustainable behavior on the wealth of the shareholders involved in M&A transactions [

5,

6] and, second, we consider the impact of M&As on external shareholders’ performance [

7]. Both approaches are based on the value created as a result of M&As, which is, as a main purpose, to support the prosperity of future generations [

8]. The efficiency of corporate M&A in organizational change can be seen as a result of the acquirers’ influence in the activity of targets, considering the two main categories of stakes: the one that grants the acquirers the control of the acquired companies and the second, which doesn’t allow the transfer of corporate control, also known as minority acquisitions [

9]. Valdone et al. [

10] distinguish between three types of deals related to M&As: acquisitions, which involve an acquirer that purchases at least 50% plus one shares in the target company, minority stakes, representing stakes that are purchased but lower than 50%, and development capital, where the specific type of minority stake investment typically involves venture capitals or private equity firms investing in early-stage companies, providing new financial resources and managerial expertise with the aim of supporting their growth. The motives for the two main types of transactions are clearly stated in literature. In the first case, the participants invoke synergy, agency or hubris [

11,

12,

13]. In the second case, the motives are more varied and start from providing the acquirers with a certain degree of influence over the target’s decisions [

14], to benefiting from the target’s profitability, materialized under the form of dividends. To these, we may add sharing technology [

15], developing joined products [

16] or mitigating financial constraints [

17].

In terms of the sustainable approach and how it is shared between the two parties, scientific literature is mainly focused on acquisitions of a controlling interest [

7,

18]. Additionally, in the present day, we often meet the term green M&A, referring to transactions with the aim of acquiring energy saving and emission-reducing technologies or transforming to other low pollution and low energy industries by heavily polluting enterprises [

5,

19]. In context, some studies [

20] found a positive impact of corporate social responsibility and of environmental social governance on the wealth of the shareholders involved in green M&As, starting from the same premise, of the growth strategies that lead to a decrease in the level of pollution of some companies that activate in high-polluting industries in developed countries (UK and USA).

The idea of a socially responsible behavior has extended, over time into emerging economies, given the fact that the benefits of respecting ethical principles in business and of giving consideration to stakeholders’ opinion was proven to have a positive impact on financial performance, reflected in profit [

21], despite the bureaucracy, corruption, the risk of receivables non collecting receivables, poor infrastructure and misevaluation of investment opportunities [

22].

Romania is a functional market economy, which has developed mainly in the last 15 years, being considered by IMF [

23] and by FTSE Russell [

24] as an emerging economy. One of the symbols of the Romanian market’s economy is its stock exchange [

25], the financial market that includes 83 companies listed on the main market, 293 listed on an alternative market AeRO (Alternative Exchange in Romania), and 15 companies that are listed on SMT International, dedicated to financial instruments admitted to trading on a regulated market or an equivalent market with a regulated market in a third country (Bucharest Stock Exchange 2020-BSE). Considering the legislative elements that regulate the socially responsible conduct of the companies, the hard law in Romania consists of Directive 2013/34/EU of the European Parliament and Council as amended by Directive 2014/95/EU of the European Parliament and Council, which request a complementary nonfinancial statement containing information on environmental issues, social and labor, human rights, fight against corruption and bribery [

26].

Considering that the obligations regulated by the above-mentioned directive were implemented through various orders of the authorities involved in the supervision of the companies, the main rule that applies ensures sustainable reporting is mandatory for companies with at least 500 employees, and at the date of the last approved balance-sheet, regardless if they apply IAS/IFRS or local GAAP. The soft law includes BSE’s Corporate Governance Code, which is voluntary, but most of the Romanian listed companies decide to comply with it. Additionally, there is ISO 26,000 (on social responsibility) which, although it is optional, is requested by partners in Romanian contracts, ISO 14,000 (on environmental management) and ISO 9000 (on quality management) [

27].

Given the openness of the capital market and its complexity, the focus of our study represents the Romanian target companies that are listed on Bucharest Stock Exchange, due to their willingness to report on their sustainable behavior [

26], despite the fact that they can be considered polluters, according to the industry they are activae in, considering the NACE Rev.2 Classification.

Thus, we analyze the motives of the acquirers to pursue an investment in the target companies, based on their economic and social performance, on one side, and the level of pollution they exert on the environment on the other. In this context, the audit opinion of the professionals on their financial statements changes the opinions of their acquirers.

Following recent literature reviews on M&A, the research questions (RQ) are settled as:

RQ1. Does an investor have a sustainable strategy, based on financial and environmental information, when purchasing a certain amount of stake in the target company?

RQ2. The audit opinion plays an important role in the growth strategy of an investor, by offering an opinion on the financial statement of the target companies?

Thus, the objectives of this paper are twofold. On one side, we want to assess if the acquirers have a sustainable strategy, based on both financial and nonfinancial information, when purchasing a certain amount of stake in the target company, given the fact that the Romanian financial market is mainly characterized by minority acquisitions [

28]. In this respect, we consider the financial return of the target company, the way it recompensates its employees and the field it is active in, with the purpose of including it in a pollution-related category, according to the model of Halme and Huse [

29]. On the other side, we want to analyse if the audit opinion on the financial statements of the target company plays an important role in the growth strategy of an investor or it is not interested in investing in an audited company.

We use a database of 1491 Romanian M&As to explore the two dimensions of acquirers’ sustainable strategies, by analyzing the impact of the target’s economic, social, and environmental performance on the acquirers’ decision to invest in a certain amount of company stake. For this purpose, our paper is structured into three parts. The first part is dedicated to the analysis of the scientific literature, considering, on one side, the motives of the acquirers to invest in a target company and, on the other side, the role of corporate social responsibility (henceforth CSR) of the two companies in the decision to participate in M&A transactions. The second part includes the presentation of the data used, the models used in analysis, the population and the sample to be analyzed. The third part includes results and discussions.

2. M&As—Strategic and Environmentally Committed Decisions for Economic Growth

When deciding to participate in M&As, analyzing the financial performance in order to receive the synergy that leads to the maximization of shareholders’ wealth should be complemented with the social care and environmental commitment of the participating companies. For this reason, most companies presenting information about social and environmental protection actions use voluntary reporting systems, such as the guidelines in the Global Reporting Initiative (GRI), the GreenhouseGas (GHG) Protocol or the integrated reporting developed by the International Integrated Reporting Council, which consists of voluntary presentation of financial information, as well as environmental protection and social responsibility information in single report [

30]. The main issue of these reporting systems is the lack of standardization. The problem was partially solved by other voluntary standards (ISO) in terms of implementation, but not of sustainability reporting.

The motives for a company to involve in M&As, as either an acquirer or a target, can be classified from multiple perspectives. From an acquirer’s point of view, the target company can present firm-specific factors which include, among others, the financial constraints [

31], the technological and market relatedness between the involved companies [

32,

33], financial information [

34], or the sustainable approach [

7,

35]. From the acquirer’s point of view, the main reasons for closing a M&A are: synergy [

18,

34], agency [

36,

37] and hubris [

11,

38] when purchasing a controlling interest, or financing, contracting or governance motives, in the case of purchasing less than 50% of target company’s shares [

39].

When analyzing the importance of sustainable behavior in M&A transactions, we consider the position reflected in

Figure 1.

M&As are growth strategies, oriented towards increasing the value of a company and, implicitly, the wealth of the shareholders. From an acquirer’s point of view, the effect of sustainable behavior can be discussed through two distinct views: stakeholder value maximization view and shareholder expense view, with opposite influences on the economic growth resulted from M&A transactions [

40]. Seen in comparison, the first approach is based on the assumption that the interest in stakeholders’ needs leads to an increase in company transactions and, implicitly, in the shareholders’ wealth. Thus, we can talk about high and low CSR companies, first companies having a positive effect on the shareholders’ wealth, being more likely to contribute to the firms’ long-term profitability and efficiency [

41,

42], and the latter being the opposite example.

The importance of CSR consists in the long-term relationships that are constructed in a company and which should be preserved in the newly formed company (in the case of mergers) or to be transmitted to the target (in the case of acquisitions), through integration, in both implicit and explicit contracts [

43,

44]. Given the fact that explicit contracts are legally enforceable [

45], a company’s reputation, which is essential to M&A success, stands on its capacity to fulfill implicit contracts with relevant stakeholders, the most important of them being employees and customers [

40].

In line with this argument, some evidence [

46] shows that high employee satisfaction-one dimension of good social performance-improves long-term abnormal stock returns. The shareholder expense analyzes the CSR potential of the acquirer from an opposite direction, given the fact that, in this case, managers engage in socially responsible activities to help other stakeholders at the expense of shareholders [

47,

48]. Practically, any expense that is made in the name of the CSR policy of the company decreases its profits and its financial performance, thus the wealth of the shareholders. In this case, the M&A may fail if the synergy gains, reported after the transactions, do not reach the level proposed in the pre-M&A phase, in the case of acquirers with high CSR.

In the case of target companies, the future of CSR policy depends on the stake purchased by the acquirer and on the CSR policy of the involved companies. In this respect, Zeisel [

49] considers that, in the case of acquisitions of a controlling interest, CSR is very dynamic, and the target shares the socially responsible behavior of the acquirer, as a part of the integration phase. Gomes [

50] changes this perspective, asserting that an acquirer will choose a target company based on its CSR performances, while Chen et al. [

51] takes on both perspectives, namely that the acquirers’ high CSR policy leads to an increase in the value of the entity post-M&As, but a target company with a higher CSR will improve the acquirer’s firm. As a conclusion, best practices and socially responsible behavior is not something that can be imposed, but shared, being in the interest of both shareholders and stakeholders.

3. The Role of Auditing in Choosing Sustainable Target Companies: An Acquirer’s Perspective

When choosing a target company, an acquirer has two perspectives: a financial one, which can lead to potential synergies, and a nonfinancial one, which is related to the target company’s attitude towards environment, community, and people.

The role of external audit in M&As is a subject of debate in research, being mainly related to the target companies [

52,

53]. The main purpose of external audit is related to the information asymmetry between the insiders and the outsiders of a company [

54]. The external audit enhances the credibility of the disclosed financial figures provided by a company that is involved in M&As. The authors consider that the external audit reduces the information asymmetry about the target’s value, allowing a fairer price from the bidder. Additionally, the external audit can also offer a proper insight into the value of the bidding company, especially when we discuss the methods of payment chosen by the acquirer [

55,

56].

The principle is simple: the transaction is conditioned by the trust that the management of the involved companies has on the financial data provided by the two parties. If the acquiring company decides to pay the shareholders of the target company using shares, then it signals to the market that the equity securities are overvalued, requiring fewer securities to cover the transaction price. In this case, the reaction of the capital market leads to a negative value of return associated with mergers and acquisitions, causing M&A to be considered a failure. Conversely, if it decides to pay in cash or cash equivalents, then the capital market understands that the securities of the acquiring company are undervalued, requiring a larger number of such values to cover the cost of the transaction.

In this respect, Huang et al. [

57] empirically analyzed the methods of payment of shares in cross-border mergers and acquisitions and concluded that entities pay with shares the equivalent of the companies concerned in countries with high governance risk, because they do not want to pay high premiums: transactions are risky, there is a decrease in the market value of securities, their profitability decreases, and hence the rather high incidence of unfinished transactions.

The trust in the external audit in proving an unqualified opinion on the target company’s financial number is also analyzed by Xie et al. [

52], who assert that companies which are audited by Big N auditors are more probable to being acquired in a M&A transaction, especially those with high information risk (reflected in low accruals quality), due to high assurance and insurance values provided by the auditors. The assertion is also sustained by the study of Lim and Lee [

53], who found a direct relationship between the quality of the financial information provided by the target company and the success of the M&A, measured in the announcement returns recorded by the acquirers. Chang and Sun [

58] showed that a high-quality external financial statement audit also mitigates information asymmetry and, hence, reduces the impact of market-timing behavior on the company’s capital structure.

Financial reporting quality has a profound influence on decision-making, particularly for investment decisions and external auditors, through their opinions certifying the information that stands at the base of growth transactions, like M&As. On the other hand, the importance of nonfinancial information in the audit process is a less-discussed topic, despite its importance in understanding the audited company [

59]. Sierra-Garcia et al. [

60] focused on the non-financial reports by listed companies, due to the implementation of Directive 2014/95/EU [

61], and found that the highest rates of nonfinancial information corresponds to companies committed to sustainable reporting.

As a result, although the directive only imposes that the presence of the report should be certified, the external provider informs on the organization’s performance regarding environmental and social issues and the auditor corroborates the quality of the information disclosed in sustainability reports [

62,

63].

4. Hypotheses Development

In order for a company to succeed, findings suggest that it should pay interest to the needs of its both its shareholders and other stakeholders, considering the value maximization view. The sustainable behavior consist of three dimensions: economic, social, and environmental. We consider that the approach of the acquirer, when pursuing an investment in a target company, should consider factors of interest that would cover as much of the aforementioned dimensions as possible.

In relation with shareholders, one of the most important aspects is the return, as a measure for efficiency (the effect obtained, reported to the effort which generates it). In Karr’s [

64] opinion, return on equity (henceforth ROE) is the equivalent for the success of an investment, because it reflects the profits that meet or exceeds the shareholders’ investment, while Beitel and Schiereck [

65] assess the success of an M&A by comparing ROE of both acquirers and target companies, and found that the former record higher returns for their investment.

Talking about investing, the concern for employees’ well-being is a major concern for companies involved in M&As. One of the most common ways of assessing the relationship between a company and its employees is reflected in the amount the company is willing to pay under the form of salaries and other monetary incentives, as a result of explicit and implicit contracts. Moreover, we consider it greatly important to analyze how the efficiency of operational activity is reflected in the cost of employees, given the fact that usually the larger companies are more interested in their socially sustainable behavior, as a result of applying the hard or soft law in the matter.

Based on previous assumptions, we propose first two hypotheses to be tested and validated:

Hypothesis 1 (H1): The financial return of a target company influences the investment decision of an acquirer.

Hypothesis 2 (H2): The cost of employees of a target company influences the investment decision of an acquirer.

These two hypotheses respond to the first research question (RQ1) proposed in the introduction part of the paper.

The core activities of the target companies can be differentiated, according to the interest of the acquirer into: R&D and innovation [

66,

67], pollution degree [

68], market share [

69,

70] and so on. If an acquirer has interest in the sustainable behavior policy of a target company, it may be biased in analyzing its economic activity, but also place it in a different risk category, in relation to the environment [

29]. In order for the acquirer to invest, the financial and nonfinancial data of the target company plays an important role and it should, if not really must, be certified by a professional. This way, for the acquirer to take a proper decision consistent with its strategy, the offered trust and guaranteed transparency from a certified professional can help facilitate the transaction. Faithfulness and the value relevance of information are key factors in these types of deals.

In this case, we propose the next two hypotheses:

Hypothesis 3 (H3): The level of harmful environmental impact in the industry in which a target company operates influences the investment decision of an acquirer.

This hypothesis also responds to the first research question (RQ1) proposed in the introduction part of the paper.

Hypothesis 4 (H4): The professional opinion of an auditor on the financial statements of a target company influences the investment decision of an acquirer.

This hypothesis responds to the second research question (RQ2) proposed in the introduction part of the paper.

The proposed hypotheses will be tested and validated using the statistical SPSS 25.0.

5. Research Methodology

5.1. Target Population, Analysed Sample and Data Source

To test and validate the proposed research hypotheses, the study analyzed the empirical data related to 1491 M&As with known purchased stake. For 979 M&As we were able to gather necessary financial data. To confirm the research hypotheses, the data regarding M&As were gathered from two databases, for the 2010–2018 period considering only the target companies that were listed, at the date of the transaction on the Bucharest Stock Exchange. The information regarding the deals representing M&As was collected from the Zephyr database; financial information was collected from Orbis database (return on equity, value of employees’ costs, operational profit, turnover for the target company).

5.2. Models Proposed for Analysis and Data Source

To test and validate the four hypotheses, the method used was a hierarchical linear regression (HLR) in order to analyze if the chosen independent variables (ROE—return on equity, cost of employees, size of the company) explain a statistically significant amount of variance in the purchased stake, after accounting for all other variables. We controled for the degree of pollution exerted by the target companies and the existence of an audit opinion on the financial statement of these companies.

The impact of different measures of financial performance on the purchased stake is estimated through an OLS regression.

The hierarchical regression models are presented in Equations (1)–(3):

Considering a hierarchical model, we have three models, used to validate hypothesis 3 and 4.

For the third hypothesis, we propose the model presented in Equation (2).

The model presented in Equation (3) is proposed to test and validate the fourth hypothesis.

Dependent variable. The purchased stake in the target company (Stake) represents the stake purchased by the acquirer in the target company. Thus, this variable is a percentage between 0.018% (shares in jointly controlled entities) and 100% (acquisition of a controlling interest). The stakes that were purchased in Romanian acquisitions were taken from the Zephyr database, for the 2010–2018 period.

Independent variables are presented in the following paragraphs.

Return on Equity (ROE) is a performance ratio which describes the target company and it is calculated for the year before the acquisition took place. As it reflects the efficiency with which the capital of the target was used, consistent with other studies [

71,

72,

73], we considered it a reliable measure of performance for the acquired company. In some cases, the ratio could be negative, which reflects the inefficiency of the target company in using the capital. The source of the information is Orbis database, for the 2010–2018 period.

Cost of employees (Ewage) represent one of the key aspects of the people management in M&As, next to the care for the workplace, blending cultures, establishing sets of policies, practices and procedures of the two organizations, designing the new organization and its jobs, managing the loss of key personnel, and so on [

74,

75]. To underline the importance of employees for the target companies, we calculate a ratio by reporting the cost of employees to operational revenues, as suggested by Wang [

73]. Thus, we determine how much of the economic benefits, resulting from current activity, are invested in the welfare of human resources, under the form of salaries and other monetary incentives. The information was taken from the Orbis database, for 2010–2018 period.

Size of the company is measured as the natural logarithm of the turnover of the target company for the year preceding the M&A transaction (

ln(CA)) [

76,

77]. We considered this matter important because the Romanian financial market is characterized mainly by minority acquisitions and many of them refer to blue-chip companies. Thus, it matters if the acquirer purchases shares in small or large companies, because the investment, in each case, can be motivated by different objectives: to gain dividends, to use the market share of the target, to seek for solutions to financial problems or, finally, to take over the target company.

Control variables are presented below.

The study included an ordinal variable to explore if the degree of pollution, corresponding to the main activity of the target company, influences the stake purchased on Romanian market, given the sustainable nature of the transaction, as suggested by Halme and Huse [

29] and Polonsky and Zeffane [

78]. Transactions were measured based on the three-digit level of the NACE Rev.2 classification. The NACE Rev.2 codes, for the target, were taken from the Orbis database, for the 2010–2018 period.

High polluters (Hpolluters): this variable was defined as a dummy variable, where 1 represents a target company that is active in chemical (oil included), metal, paper and pulp, energy production/utilities industries and 0 represents other. Here, we included mainly the blue-chip companies on Romanian stock exchange that constitute the Bucharest Exchange Trading Index (BET Index).

Medium polluters (Mpolluters): this variable was defined as a dummy variable, where 1 represents a target company which is environmentally less harmful, consisting of manufacturing companies that represent other than the most polluting industries, and 0 represents other.

Low polluters (Lpolluters): this variable was defined as a dummy variable, where 1 represents a target company with minor environmental impacts, and 0 represents other.

Audit status is a dummy variable divided into 3 distinct variables in order to control for the influence of the audit in the stake purchase of the target company. This variable takes 3 forms: qualified audit—Audit_Q (1 for qualified and 0 for others), unqualified audit—Audit_Unq (1 for unqualified and 0 for other) and unaudited—Un_A (1 for unaudited and 0 for others). The source of information is the Orbis database for the 2010–2018 period.

Analysis of variance or ANOVA is an analysis of the statistical variation of a quantitative variable, Y, relative to one or more explanatory, categorical variables, where X and k samples are randomly extracted from k populations, and defined/classified on the basis of factor X [

79]. In our study, we considered the analysis of the means of the equity stake, and grouped the target companies by their degree of pollution, corresponding to their industry, according to the NACE Rev.2 Classification. This grouping was based on the model proposed by Halme and Huse [

29]. Thus, the hypotheses were:

H0: µHpolluters = µMpolluters = µLpolluters

H1: µi ≠ µj, ∀ i ≠ j, i = 1, …, 3 and j = 1, …, 3

We also used the post hoc tests LSD (Least Significant Difference test), to identify the differences between the k groups (in our case 3 groups, i.e. polluters, medium-polluters and low-polluters) which are significant.

6. Results

The research results aim to present the descriptive statistics for the interest variables, the results of post hoc test, and the estimates of the proposed models. The descriptive statistics for the interest variables are presented in

Table 1.

Descriptive data shows that 97.75% of the 979 transactions (or 98.5% of the 1491 transactions) with target companies listed on the BSE represent minority acquisitions. Minority acquisitions represent the acquisition of less than 50% of the shares of a target company, as suggested by Contractor et al. [

9]. The distribution for the dependent variable Stake was highly asymmetrical, with extremely high deviations from the mean. In order to smooth the series, we used the logarithmic value for this variable when estimating the regression models.

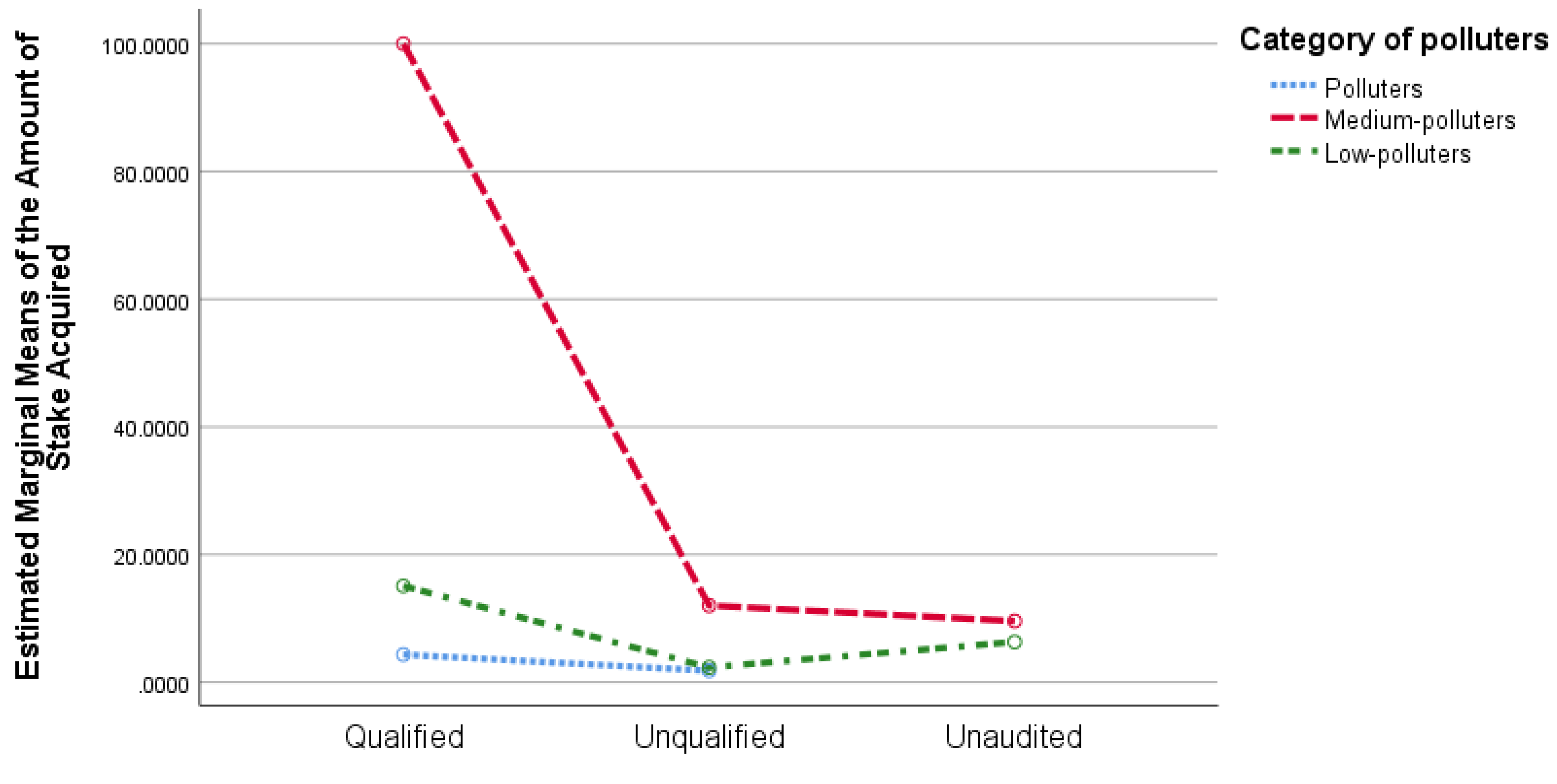

The ANOVA results, based on 1491 transactions, showed a significant difference between the means of the deal values, grouped by category of pollution of the target companies (high polluters, medium polluters, low polluters). The significance was underlined by the F-test (F (2, 1488) = 61.373) and the significance coefficient of 0.000 (p < 0.05).

According to the LSD test, presented in

Table 2, there was a significant difference between the mean purchased stake in polluting industries compared to medium polluting ones (industry), given the fact that the mean in polluters was 1.83% and in industry was 12.5%. Nonetheless, there was not a significant difference between most polluting industries and services. When using logarithmic values, the differences between means for all the groups were significant at the 1% level.

In

Table 3, we present a description of our sample, considering the category of pollution of the target companies and their audit status.

We notice that, when considering the qualified opinion in audit, most cases are in the highly polluters category (66.7%), but, in the case of unqualified opinion most target companies belong to the low pollutes (services) with 57.4%. Regardless, we must acknowledge the fact that there are no unaudited companies among the high polluting target companies, which means that the specific two digit NACE Rev.2 taken into consideration for polluters as stated by Halme and Huse [

29] must assure potential investors of their integrity and the faithfulness of their financial reporting.

The graphical representation from

Figure 2 reflects the estimated marginal means of purchased stake (absolute values).

The correlations between our numeric variables show that there was a strong negative correlation between our dependent variable (the amount of stake purchased by the acquirers), the Return on Equity of the target company (r = −0.091, sig. = 0.004), and the size of the company,

ln(CA) (r = −0.394, sig. = 0.000), and a strong and positive correlation with the cost of employees,

Ewage (r = 0.450, sig. = 0.000). To continue the study on the causality between our variables,

Table 4 displays the estimations of the parameters for the three proposed hierarchical regression models, considering the degree of pollution and the audit status of target companies as control variables.

The first model predicts how much of the variance of the dependent variable is justified by the chosen independent variables (ROE, Ewage and Size). The regression model was significant (F (3, 975) = 159.646; p < 0.001) and explained 32.9% of the variance in the dependent variable (R2 = 0.329). Related to the significance of the variables, all had a significant influence on the purchased stake, which means that the investors are interested in both the performance of the target company, considering the way it repays their investment (for ROE, sig. = 0.008) and in the welfare of the employees (for Ewage, sig. = 0.000). For ROE, the coefficient showed a negative sign, which explains the behavior of the investors in our sample of analysis. The size of the target companies confirms this.

The results show that acquirers purchase small stakes in large target companies with high return in order to collect dividends, because they consider them portfolio investments. On the Romanian M&A market, these are usually the investments in the securities of blue-chip companies that constitute the BET index, entities with good returns, a large free-float and which are subject to numerous transactions with the main purpose of generating liquidities. In this case, the acquirers are interested in how much profit a company reports, at 100 monetary units in equity, as suggested by Ahsan [

80]. When the stake increases, the takeover intentions appear, as in the case of increase-in ownership M&As, as shown by Croci and Petmezas [

81]. In the case of acquisitions of a controlling interest, the return of the target is not important, the motives of the acquirers being related to synergies, cost reductions and to increase market share, among others [

75,

82]. Additionally, they search for related or unrelated companies, depending on the strategic rationale of the M&A, surviving or expanding. On the other hand, the increase in the cost of employees has a positive influence on the purchased stake, due to the fact that the acquirers, as other studies suggest, are more interested in target companies which pay a closer eye to the well-being of their employees, as part of their social mission. The literature suggests that the acquirers’ interest in the satisfaction of their employees is later translated into a successful integration [

83,

84,

85]. The conclusions that we take from analyzing the data show two distinct behaviors of the acquirers, based on the return, the cost of employees and the size of the target companies. Data suggest that the investors will choose, in our sample of completed transactions, the most suitable strategic approach, of generating liquidities or pursuing a more expansionist strategy. The first two hypotheses are thus validated.

The second model analyzes acquirers’ decisions to invest in a specific target company belonging to a category of polluters (Hpolluters, Mpolluters, Lpolluters), considering the main activity according to the NACE Rev.2 classification. Empirical evidence suggests that, when adding the degree of pollution to the previous model as a control variable, investors are more interested in purchasing a certain amount of stake in manufacturing companies (Mpolluters), to the detriment of low polluters (service companies) (t = 5.396, sig. = 0.000), with the influence of financial information not being changed. This result is confirmed by the structure of the Romanian financial market, which consists mainly of manufacturing/industry companies. Additionally, the results suggest that the behavior of the acquirers on the Romanian M&A market is not mainly oriented towards decreasing environmental problems, but towards acquiring the target that corresponds to their investment of growth strategy, depending on the size of the purchased stake (under or over 50%). This second model adds to the significance of the variance of the dependent variable up to 45.7%. Additionally, we can notice that acquirers avoid investing in heavy polluting target companies, preferring the medium and low polluters (sig. = 0.000).

When the acquirers’ strategy takes into consideration the audit status of the target company as a control variable, the investment pattern shows a more in-depth view of the acquirers’ behavior, although it does not add much to the significance of the variance of the dependent variable (R

2 = 0.480). The results show that the behavior of the acquirers manifest two distinct patterns. On one side, they are interested in purchasing small stakes in large, audited companies, which are mainly blue-chip companies, according to the structure of the main market of the Bucharest Stock Exchange. This action discloses a profile of an acquirer interested in obtaining liquidities from investing in order to collect dividends, or from reselling securities. This is due to the fact that these target companies are improbable of being taken over or controlled, given the regulations that arise at a national and EU level. On the other side, the unaudited companies, which are listed on the AeRO market, are preferred when purchasing larger stakes and this is a key strategy of the acquirers interested in taking over target companies (sig. = 0.000, t = −6.371). The data reveal that these type of acquirers intend to expand their market share or achieve economies of scale and scope. Often, these types of transactions are made with the sole purpose of achieving synergy gains, which is consistent with the study of Rozen-Bakher [

75]. This is also consistent with prior research on the behavior of Romanian acquirers, which shows that they are more focused on horizontal and vertical M&As, compared to conglomerates [

28].

7. Conclusions

Romania is a significant investment market, for both financial and strategic investors, with buyers who try to seize the moment in a rapidly growing business environment, by either investing to increase their liquidities or to use, for strategic reasons, the value built in local businesses. In our study, the sample was mainly characterized by minority acquisitions, 97.75% of the M&A transactions representing purchases of noncontrolling stakes.

When considering the financial information that may influence the behavior of acquirers on the Romanian M&A market, when purchasing a certain amount of stake in a target company listed on BSE, we noticed two approaches. On one side, we have the financial investors, which buy small stakes in large companies, described by high values of ROE and turnover, because they want the target company’s profit to meet or exceed their investment. This is consistent with the study of Shiva and Singh [

86]. These tactical investments have a purpose of obtaining liquidities, through dividends or resales on the financial market. On the other hand, we noticed that there is a category of acquirers who are interested in purchasing the target company. For them, the return is not an information of interest, because their strategic view is related to achieving synergies [

12]. In this second case, we also noticed that the stake increases with a decrease in the size of the target company, which may suggest that the companies listed on the AeRO market (which apply local GAAP) are subject to takeover.

Additionally, our findings revealed that investors are interested in the target’s sustainable employee policy, because a secure workplace depends on the financial security of its employees. One of the most significant values, in this case, is the cost of employees (representing salaries and monetary incentives) and, more importantly, how much these expenses represent from the operational revenues of the target [

73]. In this context, the results showed that the higher the economic benefits expensed as salaries and other monetary incentives, the more attractive the target is for the acquirers.

Following the investor’s behavior regarding the strategy they apply when purchasing a certain amount of stake showed us that environmental issues do not play a significant importance when dealing with M&A transactions. The findings showed that the acquirers are more likely to purchase stakes in high and medium polluters than in service industries, considered low polluters. Moreover, 97.9% of the acquirers were not willing to invest in the 480 high polluting companies if the opinion is not unqualified, although the acquirers were searching for unaudited target companies to control. This underlines a safe investing strategy of the acquirers willing to invest on the BSE, which support their decision on the opinion of the professionals. This may be due to the fact that they are not willing to rely only on the internal control systems of the target company and required an independent professional opinion on the faithfulness of the financial information provided by the acquired company. The independent audit opinion is an unbiased one, based on the audit evidence and collected by the auditors, and is not public information, according to Romanian regulations.

One of the acknowledged limits of our study is the atypical distribution of the Romanian M&A market, mainly dominated by minority acquisitions, focusing on short-term wealth effects for the acquirers. Thus, our findings do not corroborate those provided by extensive literature, focused mainly on acquisitions of a controlling interest. The analysis of the stakes purchased in Romanian acquisitions, based on financial and nonfinancial characteristics of the target companies, completes the scarce literature on Romanian acquisitions.

Future research may consider the analysis of increase-in-ownership acquisitions and of the acquisitions of a controlling interest, in order to delimit a behavior of the acquirers, in transactions that determine the influence of the target company, especially to see if the sustainable behavior of the involved companies changes as a result of the M&A transactions.