Assessment of Geomorphosites for Geotourism in the Northern Part of the “Ruta Escondida” (Quito, Ecuador)

Abstract

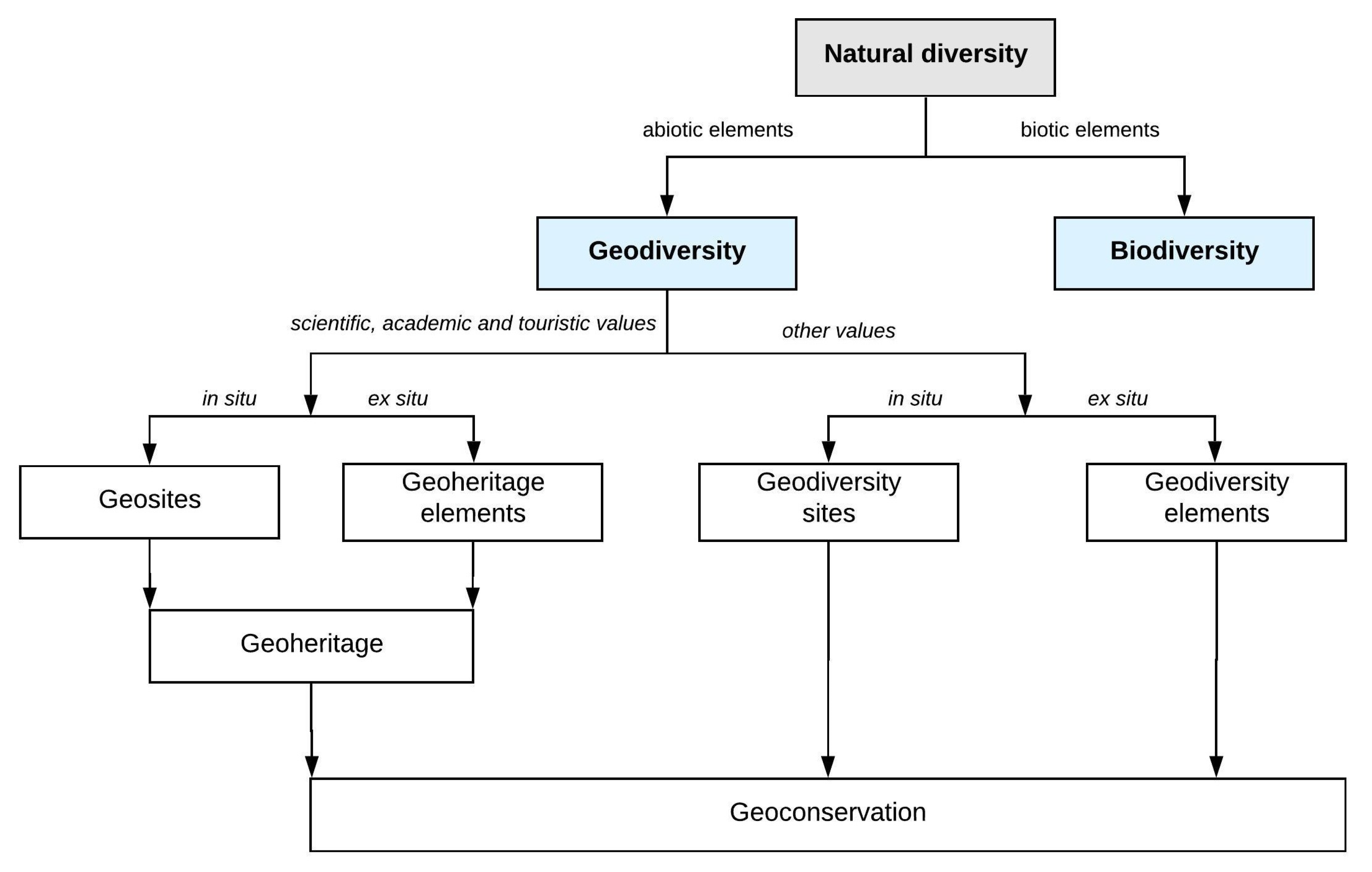

1. Introduction

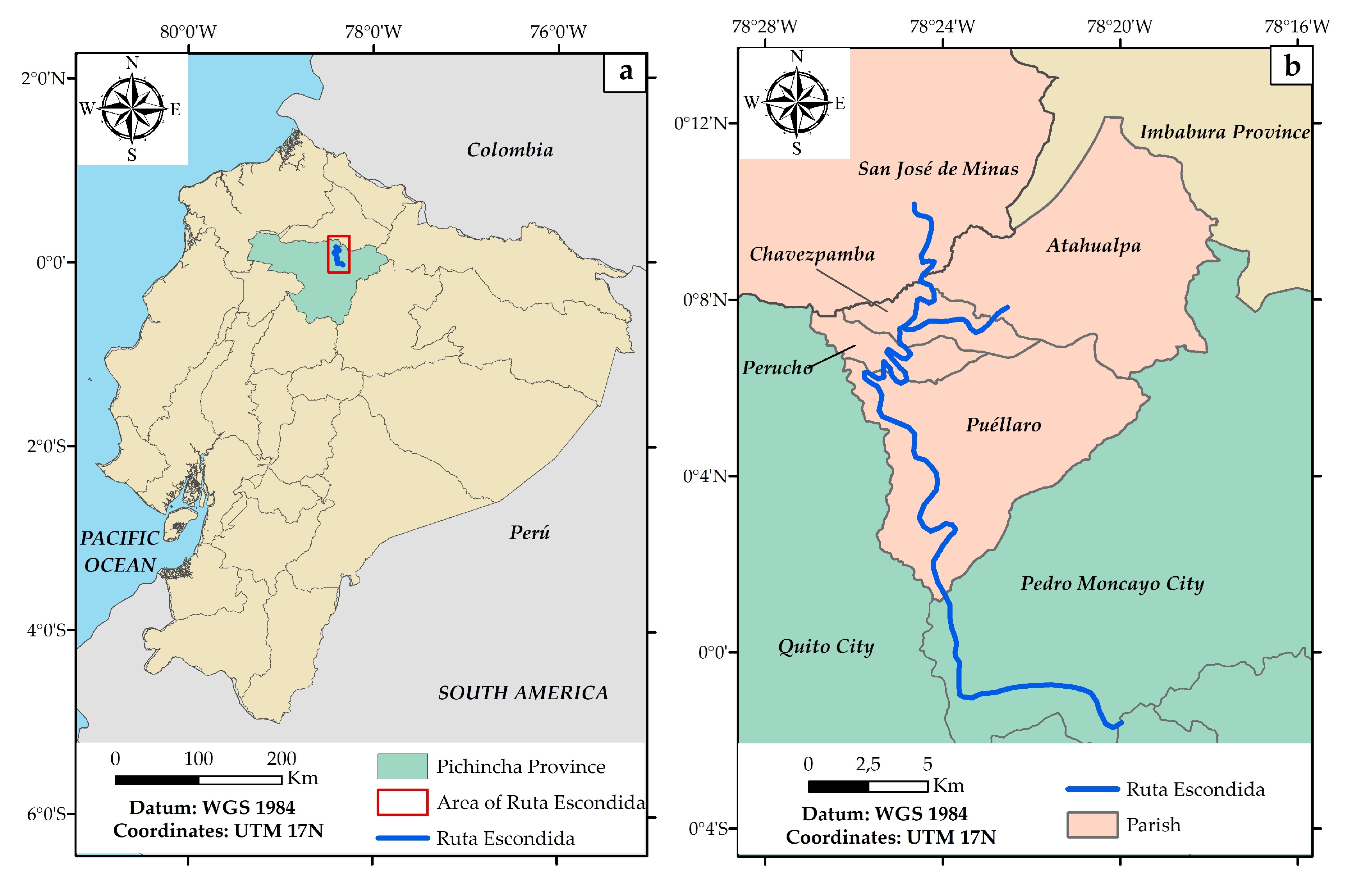

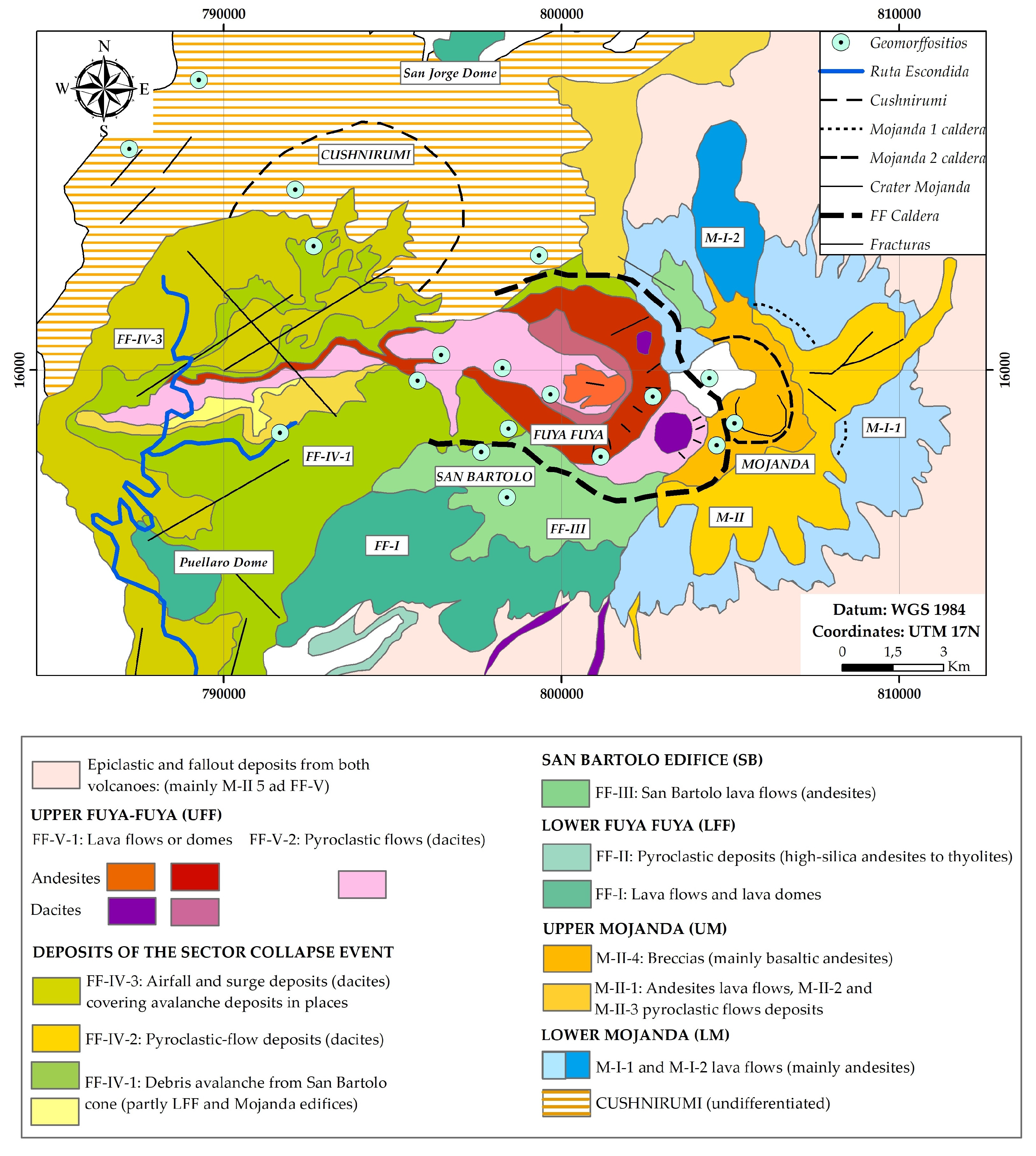

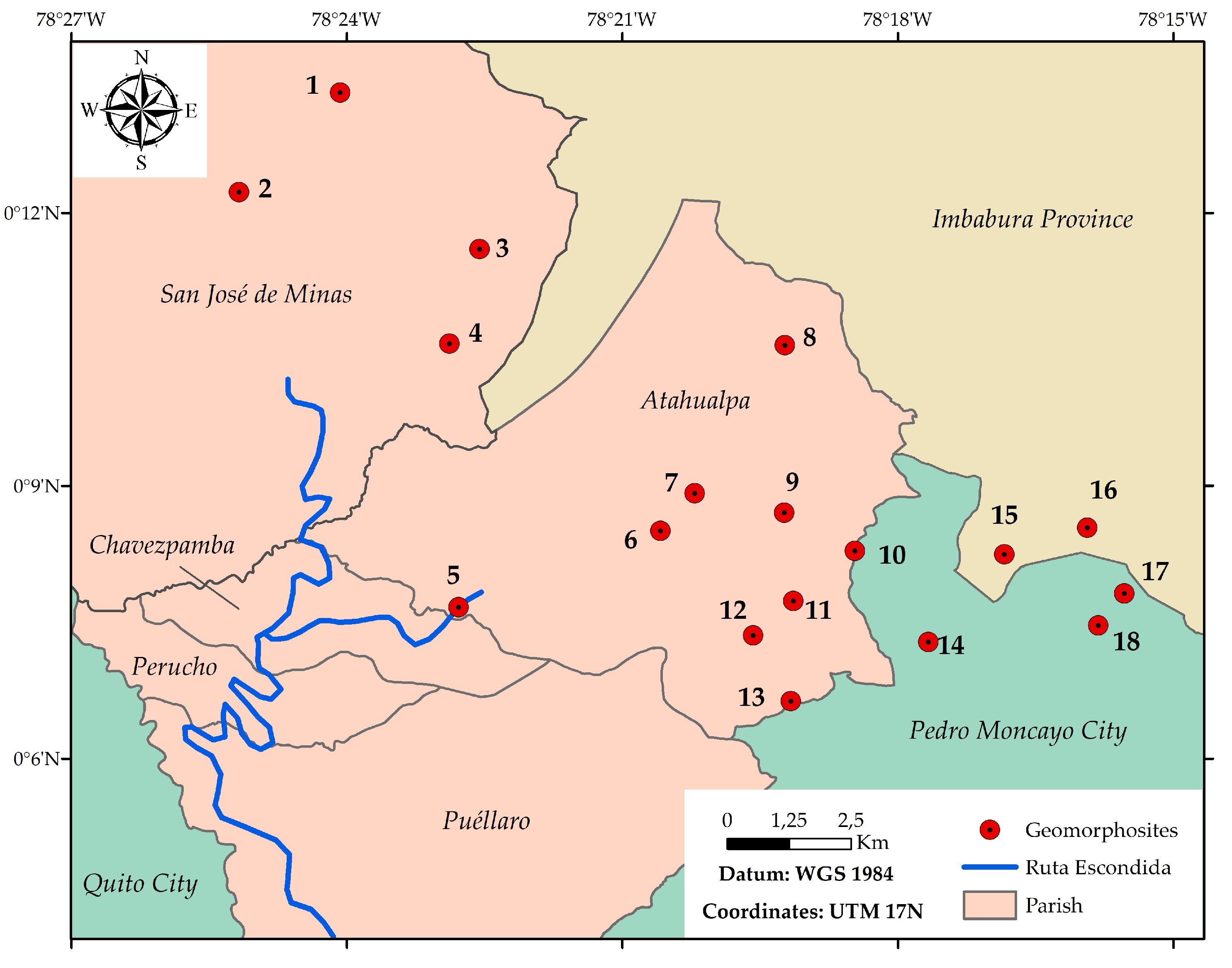

2. Geographical and Geological Setting

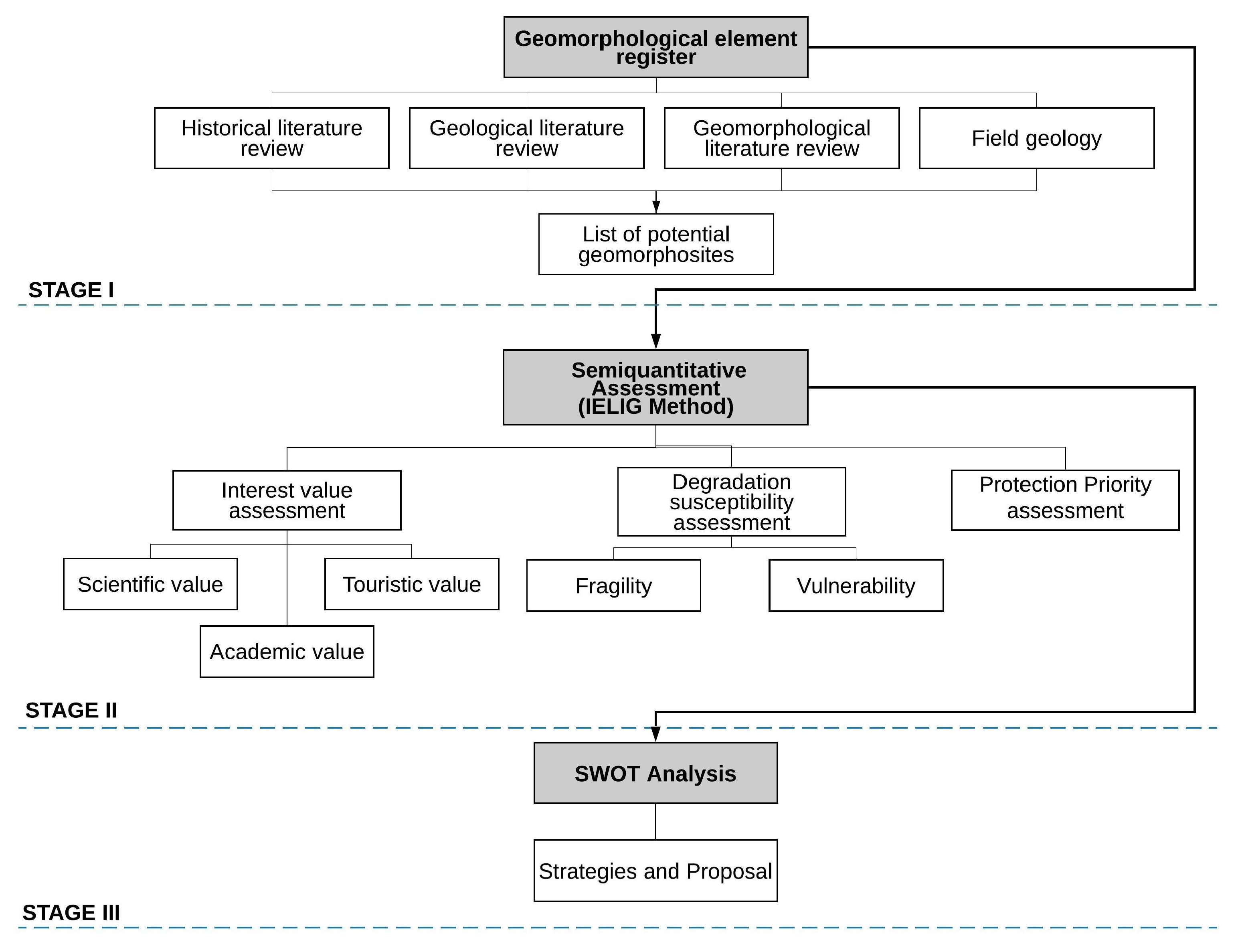

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Geomorphological Element Register

3.2. Geomorphosite Assessment

3.3. SWOT Analysis Matrix and Proposal for Geotourism

4. Results

4.1. Geomorphological Element Register

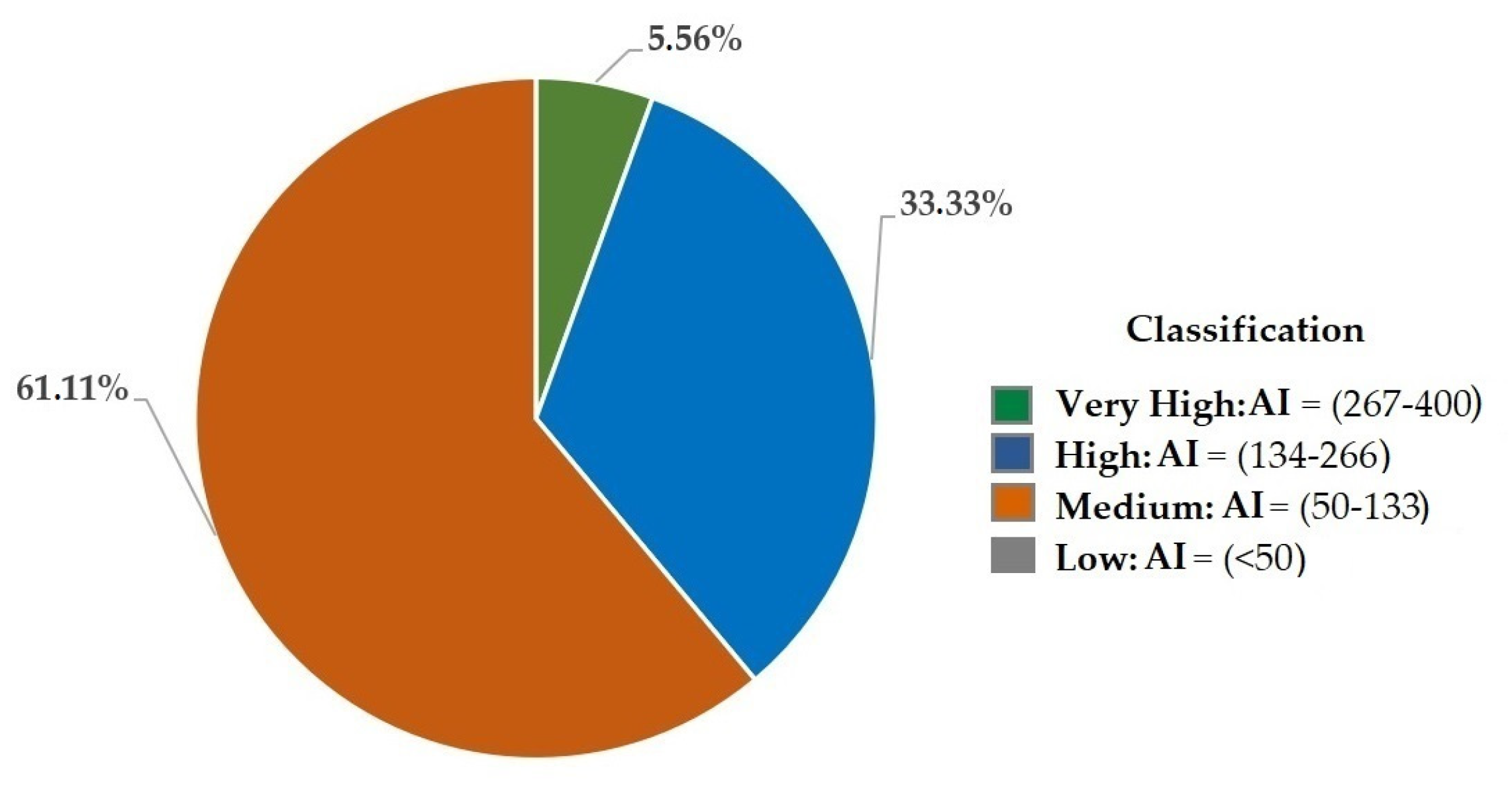

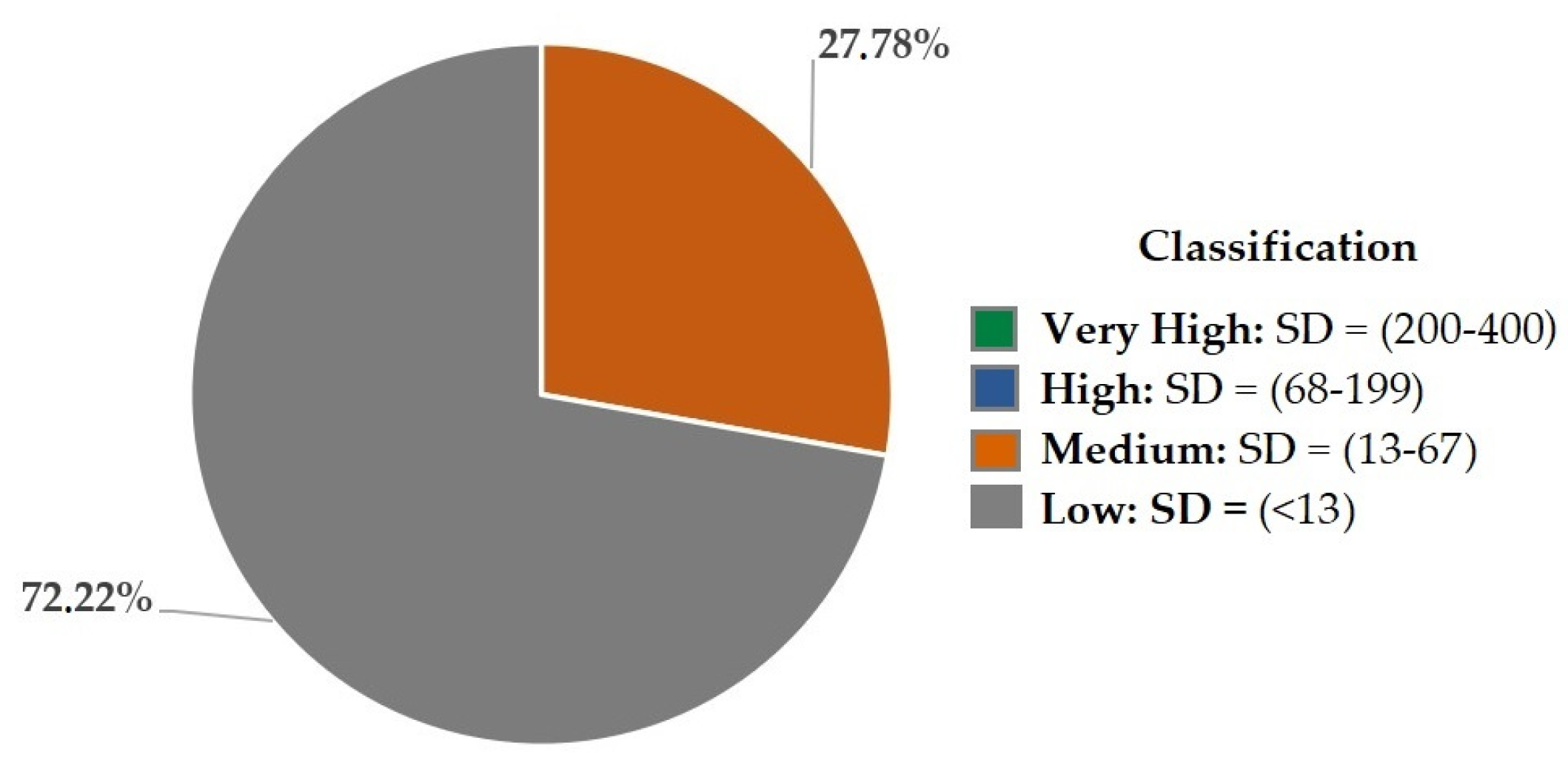

4.2. Geomorphosite Assessment

4.3. SWOT Analysis Matrix

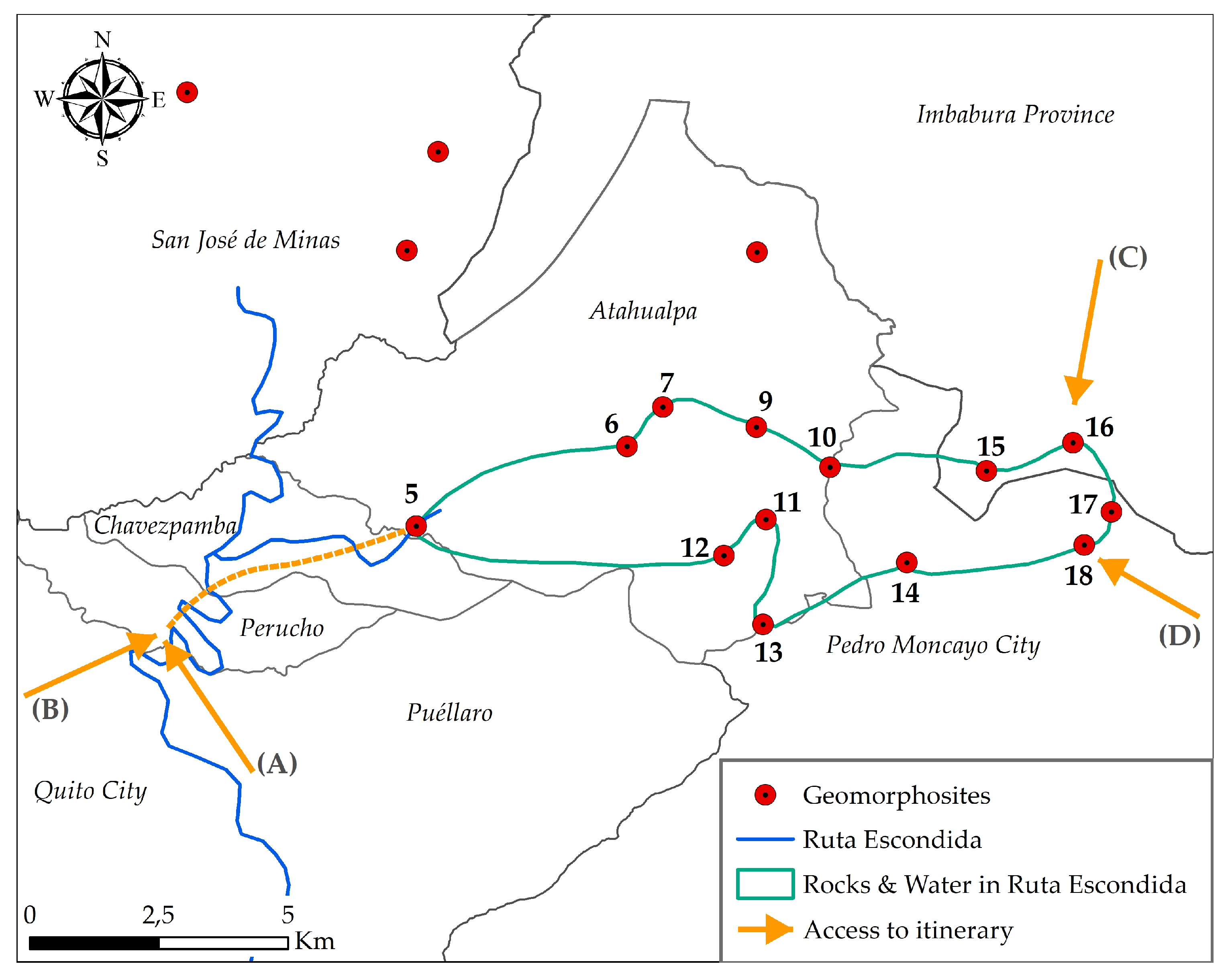

4.4. Proposed Itinerary to Visit Geomorphosites

5. Interpretation of Results and Discussion

- To promote the development of local biological, geological, archaeological and paleontological research. This initiative will allow us to recognize the scientific importance of the area at a national and international level, as well as its direct link with tourism and education.

- To promote geomorphosites as a geotourism alternative that allows the sustainable development of the area. For this, the provincial, cantonal and parochial authorities need to work with academic and business support, on the creation and adaptation of sites as tourist destinations.

- To strengthen the quality of services offered to the visitor, through the conditioning of the road infrastructure and facilities that ensure access to each geomorphosite. Additionally, to offer routes that allow visiting various geomorphosites with general and particular information (difficulty, distance, type of access).

- To reinforce territorial development plans through the implementation of regulation that ensure the conservation of geomorphosites.

- To determine the rate of erosion caused by the new activities (geotourism) and to propose initiatives that minimize the impact.

- To implement other tourist activities (trail travel, cycling, sale of handicrafts, typical food and culture) at the geomorphosites to broaden the touristic offer of the Ruta Escondida.

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Sharples, C. A Methodology for the Identification of Significant Landforms and Geological Sites for Geoconservation Purposes; Forestry Commission Tasmania: Burnie, Australia, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Wiedenbein, F.W. Origin and use of the term ‘geotope’ in German-speaking countries. In Geological and Landscape Conservation; O’Halloran, D., Green, C., Harley, M., Knill, J., Eds.; Geological Society: London, UK, 1994; pp. 117–120. [Google Scholar]

- Semeniuk, V. The linkage between biodiversity and geodiversity. In Pattern and Processes: Towards a Regional Approach to National Estate Assessment of Geodiversity; Eberhard, R., Ed.; Environment Australia: Canberra, Australia, 1997; pp. 51–58. [Google Scholar]

- Joyce, E. Assessing geological heritage. In Pattern and Process: Towards a Regional Approach to National Estate Assessment of Geodiversity; Eberhard, R., Ed.; Environment Australia: Canberra, Australia, 1997; Volume 2, pp. 35–40. [Google Scholar]

- Erikstad, L. Geoheritage and geodiversity management—The questions for tomorrow. Proc. Geol. Assoc. 2013, 124, 713–719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carcavilla, L.; Durán, J.J.; López-Martínez, J. Geodiversity: Concept and relationship with geological heritage. Geo-Temas 2008, 10, 1299–1303. [Google Scholar]

- Carcavilla, L.; Durán, J.J.; García-Cortés, Á.; López-Martínez, J. Geological Heritage and Geoconservation in Spain: Past, Present, and Future. Geoheritage 2009, 1, 75–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrión Mero, P.; Herrera Franco, G.; Briones, J.; Caldevilla, P.; Domínguez-Cuesta, M.J.; Berrezueta, E. Geotourism and local development based on geological and mining sites utilization, Zaruma-Portovelo, Ecuador. Geosciences 2018, 8, 205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gray, M. Defining Geodiversity. In Geodiversity: Valuing and Conserving Abiotic Nature; John Wiley & Sons: Chichester, UK, 2004; pp. 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Kozowski, S. Geodiversity. The concept and scope of geodiversity. Prz. Geol. 2004, 52, 833–837. [Google Scholar]

- Quesada-Román, A.; Pérez-Umaña, D. State of the art of geodiversity, geoconservation, and geotourism in Costa Rica. Geosciences 2020, 10, 211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brilha, J.; Gray, M.; Pereira, D.I.; Pereira, P. Geodiversity: An integrative review as a contribution to the sustainable management of the whole of nature. Environ. Sci. Policy 2018, 86, 19–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miljković, Ð.; Božić, S.; Miljković, L.; Marković, S.B.; Lukić, T.; Jovanović, M.; Bjelajac, D.; Vasiljević, Đ.A.; Vujičić, M.D.; Ristanović, B. Geosite Assessment Using Three Different Methods; a Comparative Study of the Krupaja and the Žagubica Springs—Hydrological Heritage of Serbia. Open Geosci. 2018, 10, 192–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Cortés, Á.; Carcavilla Urquií, L.; Apoita Mugarza, B.; Arribas, A.; Bellido, F.; Barrón, E.; Delvene, G.; Díaz-Martínez, E.; Díez, A.; Durán, J.J.; et al. Documento Metodológico para la Elaboración del Inventario Español de Lugares de Interés Geológico (IELIG); Propuesta Para la Actualización Metodológica; Instituto Geológico y Minero de España: Madrid, Spain, 2013; pp. 1–64. [Google Scholar]

- Brilha, J. Inventory and Quantitative Assessment of Geosites and Geodiversity Sites: A Review. Geoheritage 2016, 8, 119–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kot, R. The point bonitation method for evaluating geodiversity: A guide with examples (polish lowland). Geogr. Ann. Ser. A Phys. Geogr. 2015, 97, 375–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruban, D.A. Quantification of geodiversity and its loss. Proc. Geol. Assoc. 2010, 121, 326–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reynard, E.; Fontana, G.; Kozlik, L.; Scapozza, C. A method for assessing scientific and additional values of geomorphosites. Geogr. Helv. 2007, 62, 148–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serrano, E.; Ruiz-Flaño, P. Geodiversity: A theoretical and applied concept. Geogr. Helv. 2007, 62, 140–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, D.I.; Pereira, P.; Brilha, J.; Santos, L. Geodiversity Assessment of Paraná State (Brazil): An Innovative Approach. Environ. Manag. 2013, 52, 541–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Melelli, L. Geodiversity: A new quantitative index for natural protected areas enhancement. Geoj. Tour. Geosites 2014, 13, 27–37. [Google Scholar]

- Jačková, K.; Romportl, D. The Relationship Between Geodiversity and Habitat Richness in Šumava National Park and Křivoklátsko PLA (Czech Republic): A Quantitative Analysis Approach. J. Landsc. Ecol. 2008, 1, 23–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zwoliński, Z. The routine of landform geodiversity map design for the Polish Carpathian Mts. Landf. Anal. 2009, 11, 77–85. [Google Scholar]

- Forte, J.P.; Brilha, J.; Pereira, D.I.; Nolasco, M. Kernel Density Applied to the Quantitative Assessment of Geodiversity. Geoheritage 2018, 10, 205–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nobre da Silva, M.L.; Leite do Nascimento, M.A.; Leite Mansur, K. Quantitative Assessments of Geodiversity in the Area of the Seridó Geopark Project, Northeast Brazil: Grid and Centroid Analysis. Geoheritage 2019, 11, 1177–1186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrera-Franco, G.; Carrión-Mero, P.; Alvarado, N.; Morante-Carballo, F.; Maldonado, A.; Caldevilla, P.; Briones-Bitar, J.; Berrezueta, E. Geosites and georesources to foster geotourism in communities: Case study of the Santa Elena peninsula geopark project in Ecuador. Sustainability 2020, 12, 4484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brilha, J. Geoheritage and Geoparks. In Geoheritage: Assessment, Protection, and Management; Reynard, E., José, B., Eds.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2018; pp. 323–335. [Google Scholar]

- González Amuchastegui, M.J.; Serrano Cañadas, E.; González García, M. Lugares de interés geomorfológico, geopatrimonio y gestión de espacios naturales protegidos: El Parque Natural de Valderejo (Álava, España). Rev. Geogr. Norte Gd. 2014, 59, 45–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feuillet, T.; Sourp, E. Geomorphological Heritage of the Pyrenees National Park (France): Assessment, Clustering, and Promotion of Geomorphosites. Geoheritage 2011, 3, 151–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coratza, P.; Hobléa, F. The Specificities of Geomorphological Heritage. In Geoheritage: Assessment, Protection, and Management; Reynard, E., Brilha, J., Eds.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2018; pp. 87–106. [Google Scholar]

- Palacio-Prieto, J.L. Geoheritage Within Cities: Urban Geosites in Mexico City. Geoheritage 2014, 7, 365–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panizza, M. Geomorphosites: Concepts, methods and examples of geomorphological survey. Chin. Sci. Bull. 2001, 46, 4–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reynard, E.; Brilha, J. Geomorphological Heritage and Geomorphosites: Definitions. In Geoheritage: Assessment, Protection, and Management; Reynard, E., Brilha, J., Eds.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2017; pp. 88–94. [Google Scholar]

- Serrano, E.; González-Trueba, J.J. Assessment of geomorphosites in natural protected areas: The Picos de Europa National Park (Spain). Géomorphol. Relief Process. Environ. 2005, 11, 197–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albani, R.A.; Mansur, K.L.; de Souza Carvalho, I.; dos Santos, W.F.S. Quantitative evaluation of the geosites and geodiversity sites of João Dourado Municipality (Bahia—Brazil). Geoheritage 2020, 12, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reynard, E.; Paniza, M. Geomorphosites: Definition, assessment and mapping. An introduction. Géomorphol. Relief Process. Environ. 2005, 11, 177–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palacio Prieto, J. Geosites, geomorphosites and geoparks: Importance, actual situation and perspectives in Mexico. Investig. Geogr. 2013, 82, 24–37. [Google Scholar]

- Prosser, C.D.; Díaz-Martínez, E.; Larwood, J.G. The Conservation of Geosites. In Geoheritage: Assessment, Protection, and Management; Reynard, E., Brilha, J., Eds.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2018; pp. 193–212. [Google Scholar]

- Henriques, M.H.; Pena dos Reis, R.; Brilha, J.; Mota, T.S. Geoconservation as an emerging geoscience. Geoheritage 2011, 3, 17–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, R. Geoconservação e Desenvolvimento Sustentável na Chapada Diamantina (Bahia-Brasil). Ph.D. Thesis, Minho University, Braga, Portugal, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Brocx, M.; Semeniuk, V. Geoheritage and geoconservation—History, definition, scope and scale. J. R. Soc. West. Aust. 2007, 90, 53–87. [Google Scholar]

- Brilha, J. Geoconservation and protected areas. Environ. Conserv. 2002, 29, 273–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrera-Franco, G.; Montalván-Burbano, N.; Carrión-Mero, P.; Apolo-Masache, B.; Jaya-Montalvo, M. Research Trends in Geotourism: A Bibliometric Analysis Using the Scopus Database. Geosciences 2020, 10, 379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newsome, D.; Dowling, R. Geoheritage and Geotourism. In Geoheritage: Assessment, Protection, and Management; Reynard, E., Brilha, J., Eds.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2018; pp. 305–321. [Google Scholar]

- Lonsdale, P. Ecuadorian subduction system. Am. Assoc. Pet. Geol. Bull. 1978, 62, 2454–2477. [Google Scholar]

- Carrión-Mero, P.C.; Morante-Carballo, F.E.; Herrera-Franco, G.A.; Maldonado-Zamora, A.; Paz-Salas, N. The context of Ecuador’s world heritage, for sustainable development strategies. Int. J. Des. Nat. Ecodyn. 2020, 15, 39–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castillo Benalcázar, C.E. Análisis Situacional de “La Ruta Escondida” Quito-San José de Minas en la Provincia de Pichincha y Elaboración de una Guía Turística. Bachelor’s Thesis, Universidad Central del Ecuador, Quito, Ecuador, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Villacís, M.; Cantos, A.; Pons, G.; Ludeña, V. Cultural Eco-Route Mojanda-Cochasqui: A sustainable tourism development proposal for the rural area of Pichincha, Ecuador. Turismo y Sociedad 2016, 19, 121–135. [Google Scholar]

- Gaibor Chiriboga, C.V. Diseño de una Ruta Agroecoturística en las Parroquias Nor-Centrales de la Provincia de Pichincha. Bachelor’s Thesis, Universidad Central del Ecuador, Quito, Ecuador, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Ayala-Granda, A.; Carrión-Mero, P.; Paz-Salas, N.; Herrera-Franco, G.; Morante-Carballo, F.; Gurumendi-Noriega, M. Registro y valoración de geomorfositios de la zona sur de la Ruta Escondida, como alternativa de fomento a la geoconservación del paisaje en la región Caranqui-Ecuador. In Proceedings of the 18th LACCEI International Multi-Conference for Engineering, Education, and Technology, Virtual Edition, Buenos Aires, Argentina, 29–31 July 2020; pp. 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Monzier, M.; Hall, M.; Cotten, J.; Robin, C.; Mothes, P.; Eissen, J.; Samaniego, P. Les adakites d’Equateur: Modèle préliminaire. C. R. Acad. Sci. Paris 1997, 324, 545–552. [Google Scholar]

- Bourdon, E.; Eissen, J.-P.; Gutscher, M.-A.; Monzier, M.; Hall, M.L.; Cotten, J. Magmatic response to early aseismic ridge subduction: The Ecuadorian margin case (South America). Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 2003, 205, 123–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robin, C.; Eissen, J.-P.; Samaniego, P.; Martin, H.; Hall, M.; Cotten, J. Evolution of the late Pleistocene Mojanda–Fuya Fuya volcanic complex (Ecuador), by progressive adakitic involvement in mantle magma sources. Bull. Volcanol. 2009, 71, 233–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barberi, F.; Coltelli, M.; Ferrara, G. Plio–Quaternary volcanism in Ecuador. Geol. Mag. 1988, 125, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bigazzi, G.; Colteli, M.; Haadler Neto, J.; Osorio, A.; Oddone, M.; Salazar, E. Obsidian-bearing flows and pre-Colombian artifacts from the Ecuadorian Andes: First new multidisciplinary data. J. S. Am. Earth Sci. 1992, 6, 21–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, M.; Mothes, P. El Origen y Edad de la Cangahua Superior, Valle de Tumbaco, Ecuador, Quito, Ecuador. In Suelos Volcánicos Endurecidos (Quito, Diciembre 1996); Zebrowski, C., Quantin, P., Trujillo, G., Eds.; ORSTOM: Paris, France, 1997; pp. 19–28. [Google Scholar]

- Clapperton, C. Quaternary Geology and Geomorphology of South America; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Robin, C.; Hall, M.; Jimenez, M.; Monzier, M.; Escobar, P. Mojanda volcanic complex (Ecuador): Development of two adjacent contemporaneous volcanoes with contrasting eruptive styles and magmatic suites. J. S. Am. Earth Sci. 1997, 10, 345–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clapperton, C.M. Glacial geomorphology Quatemary glacial sequence and paleoclimatic inferences in the Ecuatorian Andes. Int. Geomorphol. 1987, 843–870. [Google Scholar]

- Schubert, C.; Clapperton, C.M. Quaternary Glaciations in the Northern Andes (Venezuela, Colombia and Ecuador). Quat. Sci. Rev. 1990, 9, 123–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toro, G.E.; Hermelin, M. Estudio comparativo de los paleoclimas en Colombia, Ecuador y Venezuela. In Climas Cuaternarios en Améria del Sur; Argollo, J., Mourguiart, P., Eds.; ORSTOM: La Paz, Bolivia, 1995; p. 46. [Google Scholar]

- Cáceres, B. Actualización del Inventario de Tres Casquetes Glaciares del Ecuador; Informe de Pasantía de Investigación; Université Nice Sophia Antipolis: Nice, France, 2010; pp. 10–11. [Google Scholar]

- Francou, B.; Rabatel, A.; Soruco, A.; Sicart, J.E.; Silvestre, E.; Ginot, P.; Cáceres, B.; Condom, T.; Villacís, M.; Ceballos, J.L.; et al. El retroceso de los glaciares andinos durante los últimos siglos y la aceleración del proceso desde el año 1976. In Glaciares de los Andes Tropicales: Víctimas del Cambio Climático; Silvestre, E., Francou, B., Villacís, M., Eds.; Comunidad Andina: Lima, Peru, 2013; pp. 27–41. [Google Scholar]

- Jomelli, V.; Favier, V.; Rabalet, A.; Brunstein, D.; Hoffmann, D.; Francou, B. Fluctuations of glaciers in the tropical Andes over the last millennium and palaeoclimatic implications: A review. Palaeogeogr. Palaeoclimatol. Palaeoecol. 2009, 281, 269–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayala, A. Aspectos Geológicos-Geomorfológicos y su Implicación en la Ocupación Pre-Hispánica del Período de Integración (500 d.c.–1535 d.c.), en la Ruta Escondida de la Región Caranqui. Master’s Thesis, Escuela Superior Politécnica del Litoral, Guayaquil, Ecuador, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Serrano, S. Etnoarqueología de Intercambio de Bienes y Productos en los Caminos Precolombinos de Pichincha y Napo, Ecuador. Bachelor’s Thesis, Escuela Superior Politécnica del Litoral, Guayaquil, Ecuador, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Dyson, R.G. Strategic development and SWOT analysis at the University of Warwick. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2004, 152, 631–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Štrba, L.; Rybár, P.; Baláž, B.; Moloká, M. Current Issues in Tourism Geosite assessments: Comparison of methods and results. Curr. Issues Tour. 2015, 18, 496–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Štrba, L.; Kršák, B.; Sidor, C. Some Comments to Geosite Assessment, Visitors, and Geotourism Sustainability. Sustainability 2018, 10, 2589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, P.; Pereira, D.; Caetano Alves, M.I. Geomorphosite assessment in Montesinho Natural Park (Portugal). Geogr. Helv. 2007, 62, 159–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kubalíková, L.; Kirchner, K. Geosite and Geomorphosite Assessment as a Tool for Geoconservation and Geotourism Purposes: A Case Study from Vizovická vrchovina Highland (Eastern Part of the Czech Republic). Geoheritage 2016, 8, 5–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pellitero, R.; González-Amuchastegui, M.J.; Ruiz-Flaño, P.; Serrano, E. Geodiversity and geomorphosite assessment applied to a natural protected area: The Ebro and Rudron Gorges Natural Park (Spain). Geoheritage 2010, 3, 163–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kubalíková, L. Geomorphosite assessment for geotourism purposes. Czech J. Tour. 2013, 2, 80–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reynard, E.; Perret, A.; Bussard, J.; Grangier, L.; Martin, S. Integrated Approach for the Inventory and Management of Geomorphological Heritage at the Regional Scale. Geoheritage 2016, 8, 43–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pralong, J.P. A method for assessing tourist potential and use of geomorphological sites. Géomorphol. Relief Process. Environ. 2005, 11, 189–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asociación de Servicios de Geología y Minería de Iberoamérica (ASGMI). Bases para el Desarrollo Común del Patrimonio Geológico en los Servicios Geológicos de Iberoamérica; ASGMI: Salta, Argentina, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Berrezueta, E.; Domínguez Cuesta, M.J.; Carrión, P.; Berrezueta, T.; Herrero, G. Propuesta metodológica para el aprovechamiento del patrimonio geológico minero de la zona Zaruma-Portovelo (Ecuador). Trab. Geol. 2006, 26, 103–109. [Google Scholar]

- Carrión-Mero, P.; Loor-Oporto, O.; Andrade-Ríos, H.; Herrera-Franco, G.; Morante-Carballo, F.; Jaya-Montalvo, M.; Aguilar-Aguilar, M.; Torres-Peña, K.; Berrezueta, E. Quantitative and Qualitative Assessment of the “El Sexmo” Tourist Gold Mine (Zaruma, Ecuador) as A Geosite and Mining Site. Resources 2020, 9, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrera-Franco, G.A.; Carrión-Mero, P.C.; Mora-Frank, C.V.; Caicedo-Potosí, J.K. Comparative analysis of methodologies for the evaluation of geosites in the context of the Santa Elena-Ancón geopark project. Int. J. Des. Nat. Ecodyn. 2020, 15, 183–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrera Franco, G.; Carrion Mero, P.; Morante Carballo, F.; Herrera Narváez, G.; Briones Bitar, J.; Blanco Torrens, R. Strategies for the development of the value of the mining-industrial heritage of the Zaruma-Portovelo, Ecuador, in the context of a geopark project. Int. J. Energy Prod. Manag. 2020, 5, 48–59. [Google Scholar]

- Morante-Carballo, F.; Herrera-Narváez, G.; Jiménez-Orellana, N.; Carrión-Mero, P. Puyango, Ecuador Petrified Forest, a Geological Heritage of the Cretaceous Albian-Middle, and Its Relevance for the Sustainable Development of Geotourism. Sustainability 2020, 12, 6579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrera, G.; Carrión, P.; Briones, J. Geotourism potential in the context of the Geopark project for the development of Santa Elena province, Ecuador. WIT Trans. Ecol. Environ. 2018, 217, 557–568. [Google Scholar]

- Mehdioui, S.; El Hadi, H.; Tahiri, A.; Brilha, J.; El Haibi, H.; Tahiri, M. Inventory and Quantitative Assessment of Geosites in Rabat-Tiflet Region (North Western Morocco): Preliminary Study to Evaluate the Potential of the Area to Become a Geopark. Geoheritage 2020, 12, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niculiţă, M.; Mărgărint, M.C. Landslides and Fortified Settlements as Valuable Cultural Geomorphosites and Geoheritage Sites in the Moldavian Plateau, North-Eastern Romania. Geoheritage 2018, 10, 613–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clivaz, M.; Reynard, E. How to Integrate Invisible Geomorphosites in an Inventory: A Case Study in the Rhone River Valley (Switzerland). Geoheritage 2018, 10, 527–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chingombe, W. Preliminary geomorphosites assessment along the panorama route of mpumalanga province, South Africa. Geoj. Tour. Geosites 2019, 27, 1261–1270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zgłobicki, W.; Poesen, J.; Cohen, M.; Del Monte, M.; García-Ruiz, J.M.; Ionita, I.; Niacsu, L.; Machová, Z.; Martín-Duque, J.F.; Nadal-Romero, E.; et al. The Potential of Permanent Gullies in Europe as Geomorphosites. Geoheritage 2019, 11, 217–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinnyovsky, D.; Sachkov, D.; Tsvetkova, I.; Atanasova, N. Geomorphosite Characterization Method for the Purpose of an Aspiring Geopark Application Dossier on the Example of Maritsa Cirque Complex in Geopark Rila, Rila Mountain, SW Bulgaria. Geoheritage 2020, 12, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chrobak, A.; Witkowski, K.; Szmańda, J. Assessment of the Educational Values of Geomorphosites Based on the Expert Method, Case Study: The Białka and Skawa Rivers, the Polish Carpathians. Quaest. Geogr. 2020, 39, 45–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vukoičić, D.; Ivanović, R.; Radovanović, D.; Dragojlović, J.; Martić-Bursać, N.; Ivanović, M.; Ristić, D. Assessment of geotourism values and ecological status of mines in Kopaonik mountain (Serbia). Minerals 2020, 10, 269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kubalíková, L. Assessing geotourism resources on a local level: A case study from Southern Moravia (Czech Republic). Resources 2019, 8, 150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirchner, K.; Kubalíková, L. Relief assessment methodology with respect to geoheritage based on example of the Deblínská vrchovina Highland. In Proceedings of the Public Recreation and Landscape Protection—With Man Hand in Hand, Brno, Czech Republic, 1–3 May 2013; pp. 131–141. [Google Scholar]

- Nazaruddin, D.A. Systematic Studies of Geoheritage in Jeli District, Kelantan, Malaysia. Geoheritage 2017, 9, 19–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torabi Farsani, N.; Coelho, C.; Costa, C. Geotourism and Geoparks as Gateways to Socio-cultural Sustainability in Qeshm Rural Areas, Iran. Asia Pacific J. Tour. Res. 2012, 17, 30–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, Y.; Wu, F.; Han, J.; Chu, H. Geoheritage and Sustainable Development in Yimengshan Geopark. Geoheritage 2019, 11, 991–1003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Geosite Assessment Model (IELIG) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Indicators | Values | Weight | |||

| Parameters | Sc | Ac | To | ||

| Representativeness | 0–4 | 30 | 5 | 0 | |

| Standard or reference site | 10 | 5 | 0 | ||

| Knowledge of the site | 15 | 0 | 0 | ||

| State of conservation | 10 | 5 | 0 | ||

| Conditions of observation | 10 | 5 | 5 | ||

| Scarcity, rarity | 15 | 5 | 0 | ||

| Geological diversity | 10 | 10 | 0 | ||

| Educational values | 0 | 20 | 0 | ||

| Logistics infrastructure | 0 | 15 | 5 | ||

| Population density | 0 | 5 | 5 | ||

| Possibilities for public outreach (accessibility) | 0 | 15 | 10 | ||

| Size of site | 0 | 0 | 15 | ||

| Association with other natural elements | 0 | 5 | 5 | ||

| Beauty | 0 | 5 | 20 | ||

| Informative value | 0 | 0 | 15 | ||

| Possibility of recreational and leisure activities | 0 | 0 | 5 | ||

| Proximity to other places of interest | 0 | 0 | 5 | ||

| Socio-economic situation | 0 | 0 | 10 | ||

| Total | 100 | 100 | 100 | ||

| Susceptibility | ||

|---|---|---|

| Parameter/Characteristics | Fr | |

| Value | Weight | |

| Geosite size | 0–4 | 40 |

| Vulnerability to looting | 30 | |

| Natural hazards | 30 | |

| Total Value | 100 | |

| Parameter/Characteristics | Vul | |

| Value | Weight | |

| Proximity to infrastructures | 0–4 | 20 |

| Mining exploitation interest | 15 | |

| Protected area designation | 15 | |

| Indirect protection | 15 | |

| Accessibility | 15 | |

| Ownership status | 10 | |

| Population density | 5 | |

| Proximity to recreational areas | 5 | |

| Total Value | 100 | |

| DS | ||

| DS: (Fr × Vul)/400 | (>400) Maximum (400–200) Very high (199–68) High (67–13) Medium (<13) Low | |

| PROTECTION | |

|---|---|

| Ec. 1 | |

| Ec. 2 | |

| Ec. 3 | |

Ec. 4 | (>400) Maximum (400–113) Very high (113–17) High (16–1) Medium (0) Low |

| N° | Geomorphosite | Type | Main Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Cimas de San José de Minas | Sharp peaks | These geomorphosites have slopes between 70 and 100%, located in the Atahualpa and San José de Minas sectors. |

| 2 | Relieves de Chavezpamba y San José de Minas | Mountainous relief | Most of the area presents geoforms with sharp and rounded peaks, slopes between the range 12–25% in the sectors of Puéllaro and Perucho and 70–100% in Atahualpa and San José de Minas. |

| 3 | Relieve de San José de Minas | Volcanic relief | Reliefs, product of the volcanism of the area, are found on the slopes of Mojanda and Fuya Fuya. |

| 4 | Piedemonte San José de Minas | Foothills | Plain located next to the volcanic Cushnirumi, consisting of colluvial alluvial material and deposits of the Fuya Fuya. |

| 5 | Valle Atahualpa | Valley | Valley of sand, gravel and blocks of variable composition, located in the Atahualpa and San José de Minas sectors. |

| 6 | Coluviones de Atahualpa | Colluvium | Geoforms of sand with blocks of one meter in diameter are found throughout the study area. |

| 7 | Domo Atahualpa | Volcanic dome | Small dome located in the Atahualpa forest, composed of lava with a high content of silica. |

| 8 | Cima de Atahualpa | Peaks | Peaks in the Atahualpa sector with slopes between 60 and 80% and some similarity to those of San José de Minas. |

| 9 | Terrazas de Atahualpa | Hanging terrace | Morphological unit of tectonic origin, with slopes between 2 and 12%, constituted of andesitic tuffs, covered with deposits from the Fuya Fuya. |

| 10 | Domo El Panecillo | Volcanic dome | Dome constituted of andesitic and dacitic lava flows, on its southwest side evidence of the collapse can be seen. |

| 11 | Pendiente Fuya Fuya | Volcanic spreading slope | A steep slope of tectonic origin, through which avalanche flows descended from the Fuya Fuya volcano. |

| 12 | Flujos de Atahualpa | Lahar flow | Pyroclasts from the Fuya Fuya volcano are found throughout the route, except in Perucho parish. |

| 13 | Relieve de Atahualpa | Volcanic relief | Volcanic reliefs similar to those present in San José de Minas. In the lower part they present rounded shapes, as a product of erosion. |

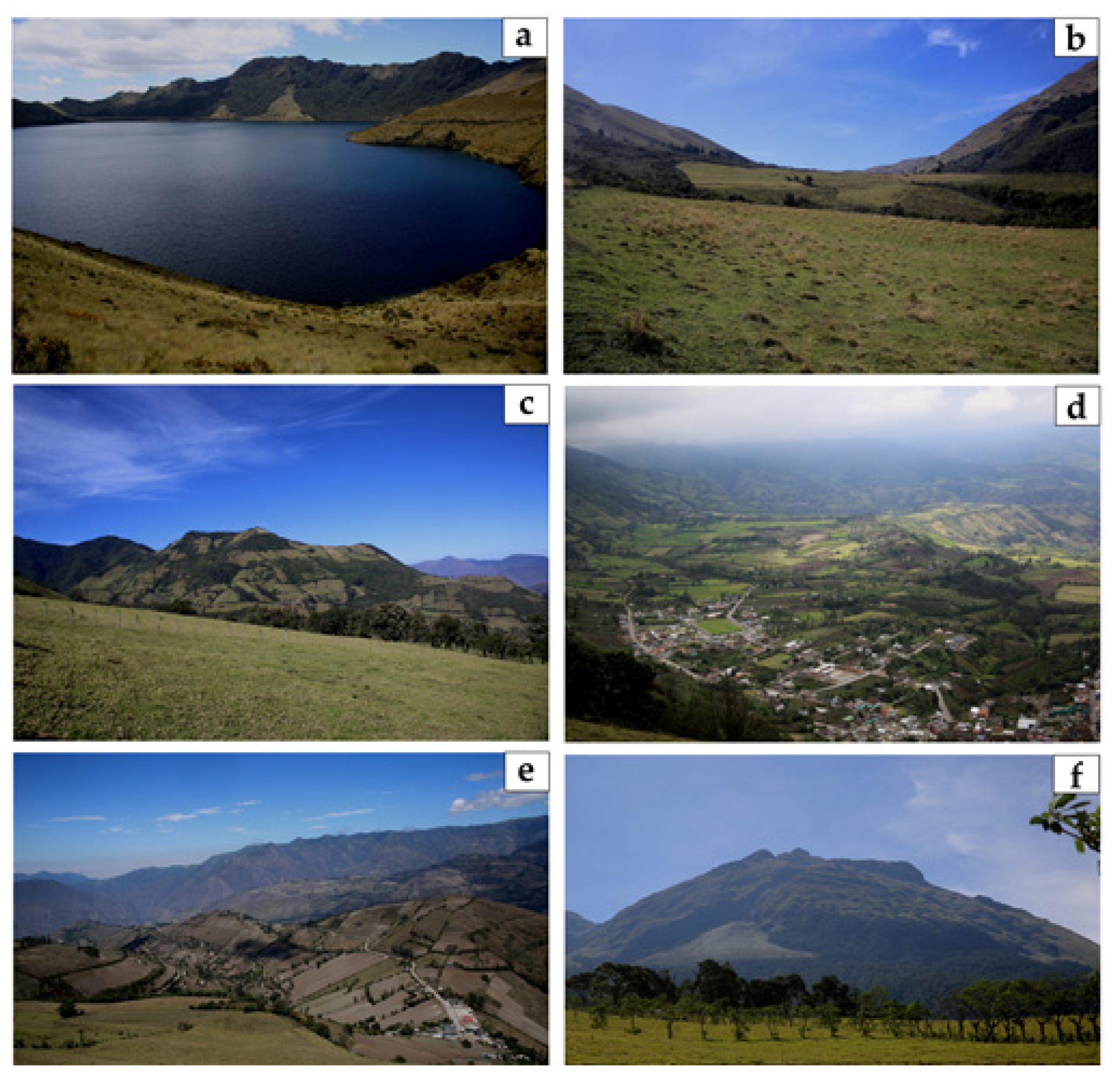

| 14 | Valle de San Bartolo–Fuya Fuya | Glacial valley | U-shaped valley consists of Mojanda glacial deposits. The valley is constituted of the San Bartolo cone and the Fuya Fuya domes. |

| 15 | Montículos Fuya Fuya | Glacial moraines | Small rounded hill, constituted of heterogeneous and sub-rounded material, as a product of the advance of the ice, which is located next to the Laguna Mojanda. |

| 16 | Laguna de Mojanda | Lagoon | The lagoon is in the caldera of the Mojanda volcano, on top of basaltic andesites and sediments interspersed with volcanic ash. |

| 17 | Macizo Mojanda | Rock massif | Rocky massif constituted of andesitic lavas from the Mojanda volcanic complex. |

| 18 | Flujos Mojanda | Flows | Flows situated under the rocky massifs, in areas with intense erosion. |

| N° | Geomorphosite | Interests | Average Interest (AI) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sc | Ac | To | |||

| 1 | Cimas de San José de Minas | 145 | 115 | 135 | 132 |

| 2 | Relieves de Chavezpamba y San José de Minas | 100 | 95 | 135 | 110 |

| 3 | Relieve de San José de Minas | 110 | 115 | 160 | 128 |

| 4 | Piedemonte San José de Minas | 75 | 110 | 150 | 112 |

| 5 | Valle Atahualpa | 240 | 160 | 125 | 175 |

| 6 | Coluviones de Atahualpa | 120 | 65 | 105 | 97 |

| 7 | Domo Atahualpa | 135 | 105 | 170 | 137 |

| 8 | Cima de Atahualpa | 130 | 130 | 145 | 135 |

| 9 | Terrazas de Atahualpa | 90 | 80 | 140 | 103 |

| 10 | Domo El Panecillo | 240 | 175 | 190 | 267 |

| 11 | Pendiente Fuya Fuya | 120 | 115 | 160 | 132 |

| 12 | Flujos de Atahualpa | 110 | 80 | 105 | 130 |

| 13 | Relieve de Atahualpa | 115 | 110 | 112 | 113 |

| 14 | Valle de San Bartolo—Fuya Fuya | 130 | 110 | 150 | 130 |

| 15 | Montículos Fuya Fuya | 105 | 85 | 120 | 103 |

| 16 | Laguna de Mojanda | 325 | 250 | 225 | 267 |

| 17 | Macizo Mojanda | 225 | 145 | 195 | 188 |

| 18 | Flujos Mojanda | 175 | 160 | 190 | 175 |

| N° | Geomorphosite | Susceptibility | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| F | Vul | SD | ||

| 1 | Cimas de San José de Minas | 0 | 25 | 0 |

| 2 | Relieves de Chavezpamba y San José de Minas | 30 | 80 | 6 |

| 3 | Relieve de San José de Minas | 110 | 100 | 27.50 |

| 4 | Piedemonte San José de Minas | 100 | 145 | 36.25 |

| 5 | Valle Atahualpa | 70 | 140 | 24.50 |

| 6 | Coluviones de Atahualpa | 100 | 100 | 25 |

| 7 | Domo Atahualpa | 0 | 25 | 0 |

| 8 | Cima de Atahualpa | 0 | 25 | 0 |

| 9 | Terrazas de Atahualpa | 0 | 70 | 0 |

| 10 | Domo El Panecillo | 0 | 115 | 0 |

| 11 | Pendiente Fuya Fuya | 0 | 80 | 0 |

| 12 | Flujos de Atahualpa | 80 | 160 | 32 |

| 13 | Relieve de Atahualpa | 40 | 80 | 8 |

| 14 | Valle de San Bartolo—Fuya Fuya | 0 | 55 | 0 |

| 15 | Montículos Fuya Fuya | 80 | 25 | 5 |

| 16 | Laguna de Mojanda | 0 | 70 | 0 |

| 17 | Macizo Mojanda | 0 | 55 | 0 |

| 18 | Flujos Mojanda | 0 | 85 | 0 |

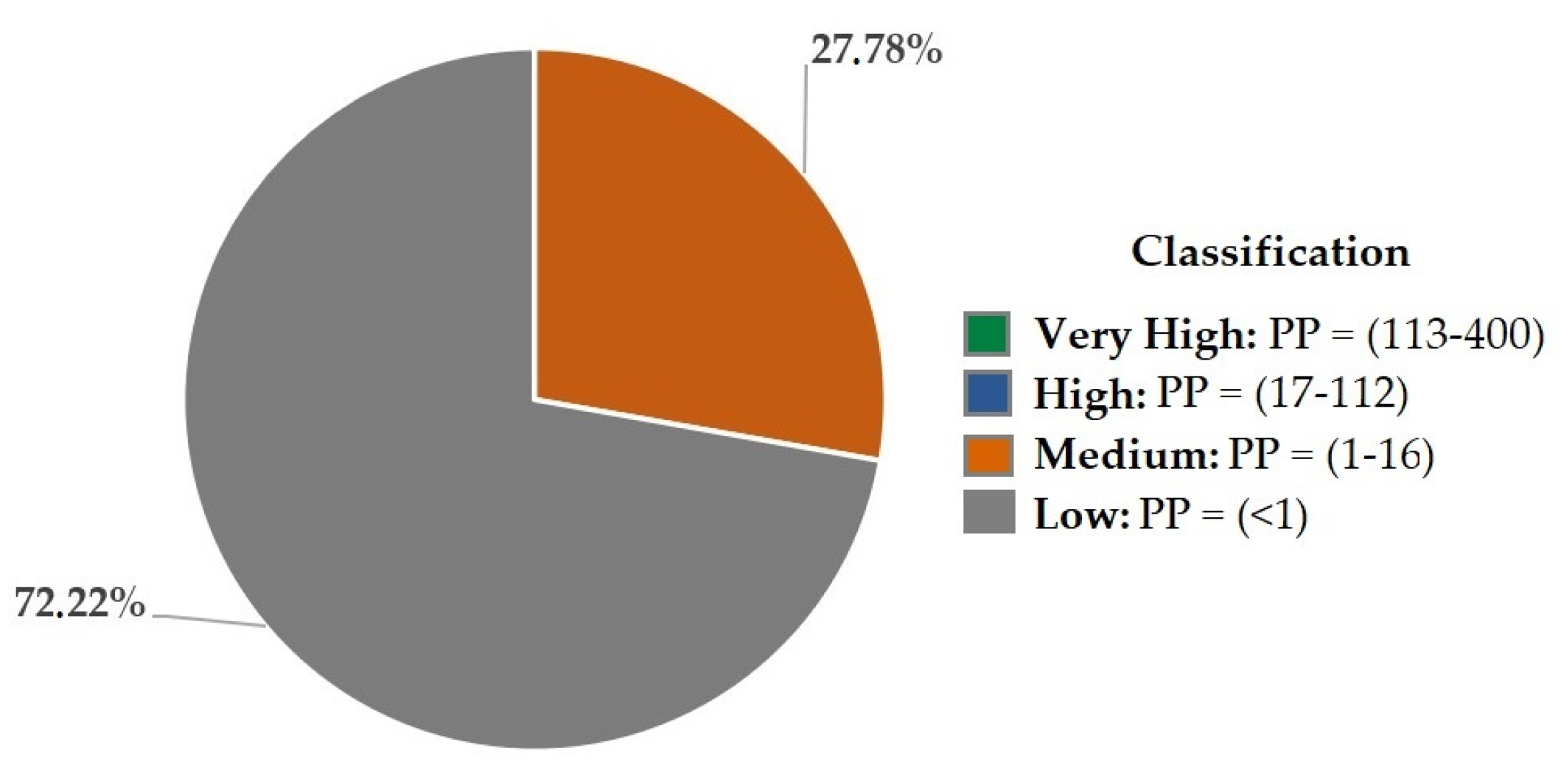

| N° | Geomorphosite | Protection Priority | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PP (Sc) | PP (Ac) | PP (To) | PP | ||

| 1 | Cimas de San José de Minas | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 2 | Relieves de Chavezpamba y San José de Minas | 0.38 | 0.34 | 0.68 | 0.45 |

| 3 | Relieve de San José de Minas | 2.08 | 2.27 | 4.40 | 2.83 |

| 4 | Piedemonte San José de Minas | 1.27 | 2.74 | 5.1 | 2.83 |

| 5 | Valle Atahualpa | 8.82 | 3.92 | 2.39 | 4.69 |

| 6 | Coluviones de Atahualpa | 2.25 | 0.66 | 1.72 | 1.46 |

| 7 | Domo Atahualpa | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 8 | Cima de Atahualpa | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 9 | Terrazas de Atahualpa | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 10 | Domo El Panecillo | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 11 | Pendiente Fuya Fuya | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 12 | Flujos de Atahualpa | 2.42 | 1.28 | 2.21 | 1.93 |

| 13 | Relieve de Atahualpa | 0.66 | 0.61 | 0.66 | 0.64 |

| 14 | Valle de San Bartolo–Fuya Fuya | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 15 | Montículos Fuya Fuya | 0.34 | 0.23 | 0.45 | 0.33 |

| 16 | Laguna de Mojanda | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 17 | Macizo Mojanda | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 18 | Flujos Mojanda | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Strengths | Weaknesses | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Internal Environment |

|

| |

| External Environment | |||

| Opportunities | Strategies: Strengths + Opportunities | Strategies: Weaknesses + Opportunities | |

| 1-a. Promote geomorphosites that illustrate the importance of the natural environment of the region. 2-e. Strengthen links between rural communities and academia for future research in different scientific areas. 3-d. Promote natural resources by each parish government to publicize geological resources. 5-c. Build awareness in the community about geomorphosites and their importance in the geotourism sector. 6-d. Access to places in good condition, which favors geotourism development. | 1-a. Assess geological elements in the scientific, educational and tourist fields for their promotion to the community. 2-c. Train local community about protection measures that geomorphosites need due to anthropic activity. 3-c. Provide training on the preservation and importance of the resources that nature offers. 4-c. Promote geotourism development nationwide through documentaries. 6-d. Monitor access roads to geomorphosites to ensure geotourism. | |

| Threats | Strategies: Strengths-Threats | Strategies: Weaknesses-Threats | |

| 2-c. Scientific development of research institutions through funding from public and private organizations. 3-b. Implementation of protection measures for geological and cultural heritage. | 1-c. Implementation of programs that cultivate funds aimed at the assessment of the geological elements. 3-a. Documentaries about geological resources. | |

| N° | Site | Type | Main Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Río Cubí | Natural wealth | Waterfalls, rich vegetation and several species of birds. |

| 2 | Museo de Perucho: Arqueología e Historia | Cultural wealth | Museum of the Ruta Escondida pre-Columbian history. |

| 3 | Iglesia de Perucho | Cultural wealth | Wooden structure, built in 1700, with a sober style and austerity touch. |

| 4 | Cerro Itagua | Natural wealth | Natural viewpoint to observe the Chacezpamba parish, the Fuya Fuya hill and the Mojanda forest. |

| 5 | Iglesia Parroquial de Chavezpamba | Cultural wealth | Brick, clay and wood structure, built in 1950. |

| 6 | Aguas termales de Atahualpa | Natural wealth | Thermal water spa, rivers and vegetation. |

| 7 | Camposanto de Atahualpa | Cultural wealth | Site with cypress trees molded to different shapes, such as bears and birds. |

| 8 | Iglesia Parroquial de Atahualpa | Cultural wealth | Church built in 1923 with community collaboration. Contains a legendary rock with the image of the Virgen del Quinche. |

| 9 | Bosque protector Mojanda | Natural wealth | A forest of approximately 1200 hectares, with several species of native Andean flora, of which two areas have been declared protective forest. |

| Itinerary | Interest | Susceptibility | Protection Priority | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sc | Ac | To | AI | Vul | Fr | DS | Sc | Ac | To | Pp | |

| “Rocks & Water in Ruta Escondida” | 163.8 | 113.8 | 152.8 | 143.5 (High) | 81.5 | 28.5 | 5.80 (Low) | 1.1 | 0.5 | 0.6 | 0.7 (Low) |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Carrión-Mero, P.; Ayala-Granda, A.; Serrano-Ayala, S.; Morante-Carballo, F.; Aguilar-Aguilar, M.; Gurumendi-Noriega, M.; Paz-Salas, N.; Herrera-Franco, G.; Berrezueta, E. Assessment of Geomorphosites for Geotourism in the Northern Part of the “Ruta Escondida” (Quito, Ecuador). Sustainability 2020, 12, 8468. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12208468

Carrión-Mero P, Ayala-Granda A, Serrano-Ayala S, Morante-Carballo F, Aguilar-Aguilar M, Gurumendi-Noriega M, Paz-Salas N, Herrera-Franco G, Berrezueta E. Assessment of Geomorphosites for Geotourism in the Northern Part of the “Ruta Escondida” (Quito, Ecuador). Sustainability. 2020; 12(20):8468. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12208468

Chicago/Turabian StyleCarrión-Mero, Paúl, Alicia Ayala-Granda, Sthefano Serrano-Ayala, Fernando Morante-Carballo, Maribel Aguilar-Aguilar, Miguel Gurumendi-Noriega, Nataly Paz-Salas, Gricelda Herrera-Franco, and Edgar Berrezueta. 2020. "Assessment of Geomorphosites for Geotourism in the Northern Part of the “Ruta Escondida” (Quito, Ecuador)" Sustainability 12, no. 20: 8468. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12208468

APA StyleCarrión-Mero, P., Ayala-Granda, A., Serrano-Ayala, S., Morante-Carballo, F., Aguilar-Aguilar, M., Gurumendi-Noriega, M., Paz-Salas, N., Herrera-Franco, G., & Berrezueta, E. (2020). Assessment of Geomorphosites for Geotourism in the Northern Part of the “Ruta Escondida” (Quito, Ecuador). Sustainability, 12(20), 8468. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12208468