Unraveling the Effects of Ethical Leadership on Knowledge Sharing: The Mediating Roles of Subjective Well-Being and Social Media in the Hotel Industry

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Background and Hypothesis Development

2.1. Ethical Leadership (EL)

2.2. Knowledge Sharing (KS)

2.3. Perceived Supervisor Support (PSS) Theory

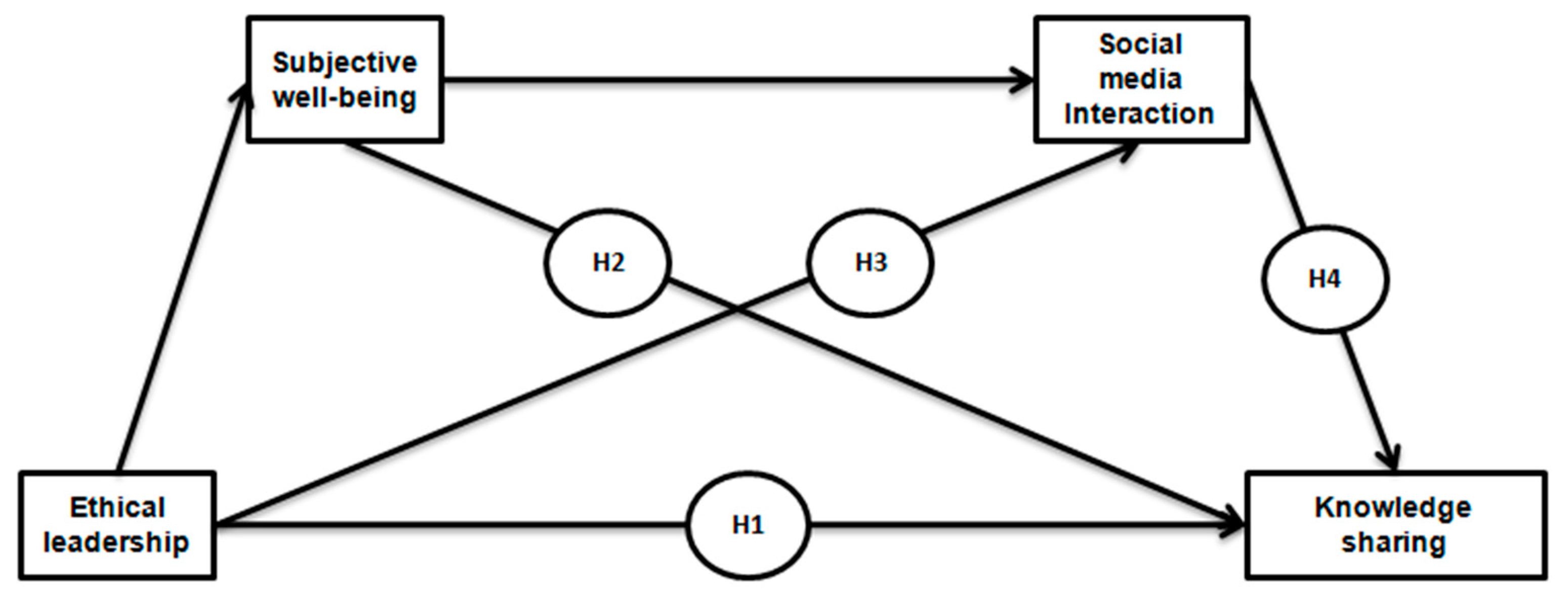

2.4. Ethical Leadership (EL) and Knowledge Sharing (KS)

2.5. Mediating Role of Subjective Well-Being (SWB)

2.6. Mediating Role of Social Media (SM)

2.7. Sequential Mediation

3. Research Methodology

3.1. Sample and Procedure

- Does your company give value employees ideas, well-being and individuality?

- Do you provide time-to-time opportunities to your staff to participate in decision making?

3.2. Survey Measures

3.3. Control Variables

3.4. Analytical Strategy

4. Results

4.1. Assessment of Measurement Model

4.2. Structural Model

4.3. Mediational Analysis Result

5. Discussion

5.1. Theoretical Contributions

5.2. Practical Contributions

5.3. Limitations and Future Research Directions

6. Conclusion

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix

| Ethical Leadership. |

| 1. My supervisor listens to what employees have to say |

| 2. My supervisor disciplines employees who violate ethical standards |

| 3. My supervisor conducts his/her personal life in an ethical manner |

| 4. My supervisor has the best interests of employees in mind |

| 5. My supervisor makes fair and balanced decisions |

| 6. My supervisor can be trusted |

| 7. My supervisor discusses business ethics or values with employees |

| 8. My supervisor sets an example of how to do things the right way in terms of ethics |

| 9. My supervisor defines success not just by results but also the way that they are obtained |

| 10. When making decisions, my supervisor asks “what is the right thing to do?” |

| Tacit Knowledge Sharing |

| 1. Share knowledge based on our experience |

| 2. Collect knowledge from others based on our experience |

| 3. Share knowledge of know-where or know-whom with others |

| 4. Collect knowledge of know-where or know-whom with others |

| 5. Share knowledge based on our expertise |

| 6. Collect knowledge from others based on our expertise |

| 7. Share lessons from past failures when we feel it is necessary |

| Explicit Knowledge Sharing |

| 1. We frequently share existing reports and official documents with members of our organization |

| 2. We frequently share reports and official documents that we prepare by ourselves with members of our organization |

| 3. We frequently collect reports and official documents from others |

| 4. We are frequently encouraged by knowledge sharing mechanisms |

| 5. We are frequently offered a variety of training and development programs |

| 6. We are facilitated by IT systems invested in knowledge sharing |

| Subjective Well-Being |

| 1. In most ways my life is close to my ideal. |

| 2. The conditions of my life are excellent. |

| 3. I am satisfied with my life. |

| 4. So far, I have gotten the important things I want in life. |

| 5. If I could live my life over, I would change almost nothing. |

| Social Media |

| 1. Using social media makes my work fast. |

| 2. Using social media makes my work easier. |

| 3. Using social media increases my working performance. |

| 4. Using social media makes my work effective. |

| 5. Using social media increases my work productivity. |

| 6. I often use social media to perform my work. |

| 7. Use of social media is helpful at my workplace. |

| 8. It is easy to learn how to use social media. |

| 9. It is easy to interact on social media. |

| 10. I like to use social media. |

References

- Jiang, Y.; Chen, C.C. Integrating knowledge activities for team innovation: Effects of transformational leadership. J. Manag. 2018, 44, 1819–1847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rhee, Y.W.; Choi, J.N. Knowledge management behavior and individual creativity: Goal orientations as antecedents and in-group social status as moderating contingency. J. Organ. Behav. 2017, 38, 813–832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srivastava, A.; Bartol, K.M.; Locke, E.A. Empowering leadership in management teams: Effects on knowledge sharing, efficacy, and performance. Acad. Manag. J. 2006, 49, 1239–1251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerpott, F.H.; Fasbender, U.; Burmeister, A. Respectful leadership and followers’ knowledge sharing: A social mindfulness lens. Hum. Elat. 2020, 73, 789–810. [Google Scholar]

- Bavik, Y.L.; Tang, P.M.; Shao, R.; Lam, L.W. Ethical leadership and employee knowledge sharing: Exploring dual-mediation paths. Lead. Q. 2018, 29, 322–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chughtai, A.; Byrne, M.; Flood, B. Linking ethical leadership to employee well-being: The role of trust in supervisor. J. Bus. Ethics 2015, 128, 53–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagyo, Y. Engagement as a variable to improve the relationship between leadership, organizational culture on the performance of employees. Iosr J. Bus. Manag. 2013, 14, 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Hartog, D.N.D. Ethical Leadership. Annu.Ev. Organ. Psychol. Organ. Behav. 2015, 2, 9–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demirtas, O.; Akdogan, A.A. The effect of ethical leadership behavior on ethical climate, turnover intention, and affective commitment. J. Bus. Ethics 2015, 130, 59–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.; Hsieh, J.J.; He, W. Expertise dissimilarity and creativity: The contingent roles of tacit and explicit knowledge sharing. J. Appl. Psychol. 2014, 99, 816–830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, T.T.; Lee, G. Hospitality employee knowledge-sharing behaviors in the relationship between goal orientations and service innovative behavior. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2013, 34, 324–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gardner, H.K.; Gino, F.; Staats, B. Dynamically integrating knowledge in teams: Transforming resources into performance. Acad. Manag. J. 2012, 55, 998–1022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donate, M.J.; Sánchez de Pablo, J.D. The role of knowledge-oriented leadership in knowledge management practices and innovation. J. Bus. Res. 2015, 68, 360–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capone, V.; Petrillo, G. Mental health in teachers: Relationships with job satisfaction, efficacy beliefs, burnout and depression. Curr. Psychol. 2018, 39, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Athota, V.S.; Budhwar, P.; Malik, A. Influence of personality traits and moral values on employee well-being, resilience and performance: A cross-national study. Appl. Psychol. 2019, 69, 653–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.; Kaufman, S.B.; Smillie, L.D. Unique associations between big five personality aspects and multiple dimensions of well-being. J. Personal. 2018, 86, 158–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diener, E.; Oishi, S.; Tay, L. Advances in subjective well-being research. Nat. Hum. Behav. 2018, 2, 253–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Risius, M.; Beck, R. Effectiveness of corporate social media activities in increasing relational outcomes. Inf. Manag. 2015, 52, 824–839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, Y.; Xu, Y.; Wang, X.; Zhang, C.; Ling, H.; Lin, L. Integrating social networking support for dyadic knowledge exchange: A study in a virtual community of practice. Inf. Manag. 2015, 52, 61–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, J.; Wu, W. Business value of social media technologies: Evidence from online user innovation communities. J. Strateg. Inf. Syst. 2015, 24, 113–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, L.; Liu, P. Ties that work: Investigating the relationships among coworker connections, work-related Facebook utility, online social capital, and employee outcomes. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2017, 72, 512–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braojos, J.; Benitez, J.; Llorens, J. How do social commerce-IT capabilities influence organizational performance? Theory and empirical evidence. Inf. Manag. 2019, 56, 155–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisenberger, R.; Stinglhamber, F.; Vandenberghe, C.; Sucharski, I.L.; Rhoades, L. Perceived supervisor support: Contributions to perceived organizational support and employee retention. J. Appl. Psychol. 2002, 87, 565–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McMurrian, R.; Matulich, E. Building Customer Value And Profitability With Business Ethics. J. Bus. Econ. Res. (JBER) 2016, 14, 83–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baum, T.; Cheung, C.; Kong, H.; Kralj, A.; Mooney, S.; Nguyễn Thị Thanh, H.; Siow, M. Sustainability and the Tourism and Hospitality Workforce: A Thematic Analysis. Sustainability 2016, 8, 809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, A.S.Y.; Hou, Y.H. The effects of ethical leadership, voice behavior and climates for innovation on creativity: A moderated mediation examination. Leadership. Quarterly. 2016, 27, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bedi, A.; Alpaslan, C.M.; Green, S. A meta-analytic review of ethical leadership outcomes and moderators. J. Bus. Ethics 2016, 139, 517–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, Q.; Wen, B.; Ling, Q.; Zhou, S.; Tong, M. How and when the effect of ethical leadership occurs? A multilevel analysis in the Chinese hospitality industry. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2014, 26, 974–1001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Keefe, D.F.; Messervey, D.; Squires, E.C. Promoting Ethical and Prosocial Behavior: The Combined Effect of Ethical Leadership and Coworker Ethicality. Ethics Behav. 2017, 28, 235–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karatepe, O.M.; Aboramadan, M.; Dahleez, K.A. Does climate for creativity mediate the impact of servant leadership on management innovation and innovative behavior in the hotel industry? Int. J. of Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2020, 32, 2497–2517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haldorai, K.; Kim, W.G.; Chang, H.S.; Li, J. Workplace spirituality as a mediator between ethical climate and workplace deviant behavior. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2019, 86, 102372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koch, J.; Gerdt, S.-O.; Schewe, G. Determinants of sustainable behavior of firms and the consequences for customer satisfaction in hospitality. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2020, 89, 102515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, R.; Ai, S.; Ren, Y. Relationship between knowledge sharing and performance: A survey in Xi’an, China. Expert Syst. Appl. 2007, 32, 38–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Noe, R.A. Knowledge sharing: A review and directions for future research. Hum. Resour. Manag. Rev. 2010, 20, 115–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brachos, D.; Kostopoulos, K.; Eric Soderquist, K.; Prastacos, G. Knowledge effectiveness, social context and innovation. J. Knowl. Manag. 2007, 11, 1–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watson, S.; Hewett, K. A multi-theoretical model of knowledge transfer in organizations: Determinants of knowledge contribution and knowledge reuse. J. Manag. Stud. 2006, 43, 141–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dysvik, A.; Kuvaas, B.; Buch, R. Perceived training intensity and work effort: The moderating role of perceived supervisor support. Eur. J. Work Organ. Psychol. 2014, 23, 729–738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puah, L.N.; Ong, L.D.; Chong, W.Y. The effects of perceived organizational support, perceived supervisor support, and perceived co-worker support on safety and health compliance. J. Contemp. Manag. 2014, 3, 86–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.L.; Yun, S. The effect of coworker knowledge sharing on performance and its boundary conditions: An interactional perspective. J. Appl. Psychol. 2015, 100, 575–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, M.E.; Treviño, L.K. Ethical leadership: A review and future directions. Leadersh. Q. 2006, 17, 595–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, M.E.; Treviño, L.K.; Harrison, D.A. Ethical leadership: A social learning perspective for construct development and testing. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Processes 2005, 97, 117–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.D.; Sung, W. Predictors of organizational citizenship behavior: Ethical leadership and workplace jealousy. J. Bus. Ethics 2016, 135, 117–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yidong, T.; Xinxin, L. How Ethical Leadership Influence Employees’ Innovative Work Behavior: A Perspective of Intrinsic Motivation. J. Bus. Ethics 2012, 116, 441–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Xing, L.; Xu, H.; Hannah, S.T. Not All Followers Socially Learn from Ethical Leaders: The Roles of Followers’ Moral Identity and Leader Identification in the Ethical Leadership Process. J. Bus. Ethics 2019, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisenbeiss, S.A.; Knippenberg, D. On ethical leadership impact: The role of follower mindfulness and moral emotions. J. Organ. Behav. 2015, 36, 182–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindebaum, D.; Geddes, D.; Gabriel, Y. Moral emotions and ethics in organizations: Introduction to the special issue. J. Bus. Ethics 2017, 141, 645–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, A.J.; Loi, R.; Ngo, H.Y. Ethical leadership behavior and employee justice perceptions: The mediating role of trust in organization. J. Bus. Ethics 2016, 134, 493–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonner, J.M.; Greenbaum, R.L.; Mayer, D.M. My boss is morally disengaged: The role of ethical leadership in explaining the interactive effect of supervisor and employee moral disengagement on employee behaviors. J. Bus. Ethics 2016, 137, 731–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouckenooghe, D.; Zafar, A.; Raja, U. How ethical leadership shapes employees’ job performance: The mediating roles of goal congruence and psychological capital. J. Bus. Ethics 2015, 129, 51–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, R.M.; Deci, E.L. On happiness and human potentials: Are view of research on hedonic and eudemonic well-being. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2001, 52, 141–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diener, E.; Biswas-Diener, R. Will money increase subjective well-being? A literature review and guide to needed research. Soc. Indic. Res. 2002, 57, 119–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chumg, H.F.; Cooke, L.; Fry, J.; Hung, I.H. Factors affecting knowledge sharing in the virtual organization: Employees’ sense of well-being as a mediating effect. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2015, 44, 70–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henttonen, K.; Kianto, A.; Ritala, P. Knowledge sharing and individual work performance: An empirical study of a public sector organization. J. Knowl. Manag. 2016, 20, 749–768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erdogan, B.; Bauer, T.N.; Truxillo, D.M.; Mansfield, L.R. Whistle while you work are view of the life satisfaction literature. J. Manag. 2012, 38, 1038–1083. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, W.; Wang, G.; Zheng, X.; Liu, T.; Miao, Q. Examining the role of personal identification with the leader in leadership effectiveness: A partial nomological network. Group Organ. Manag. 2013, 38, 36–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Celik, S.; Dedeoglu, B.B.; Ýnanýr, A. Relationship between ethical leadership, organizational commitment and job satisfaction at hotel organizations. Ege Acad. Rev. 2015, 15, 53–65. [Google Scholar]

- Mo, S.; Shi, J. Linking ethical leadership to employee burnout, workplace deviance and performance: Testing the mediating roles of trust in leader and surface acting. J. Bus. Ethics 2017, 144, 293–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.-C.; Yu, C.; Yi, C.-C. The effects of positive affect, person-job fit, and well-being on job performance. Soc. Behav. Personal. 2014, 42, 1537–1547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C. Does ethical leadership lead to happy workers? A study on the impact of ethical leadership, subjective well-being, and life happiness in the Chinese culture. J. Bus. Ethics 2014, 123, 513–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stebbins, R.A. Leisure and the positive psychological states. Posit. Psychol. 2018, 13, 8–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, D.; Witt, L.A.; Waite, E.; David, E.M.; Van Driel, M.; McDonald, D.P.; Callison, K.R.; Crepeau, L.J. Effects of ethical leadership on emotional exhaustion in high moral intensity situations. Leadersh. Q. 2015, 26, 732–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, M.; Shaheen, M.; Das, M. Engaging employees for quality of life: Mediation by psychological capital. Serv. Ind. J. 2018, 39, 403–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavaliere, V.; Lombardi, S.; Giustiniano, L. Knowledge sharing in knowledge-intensive manufacturing firms: An empirical study of its enablers. J. Knowl. Manag. 2015, 19, 1124–1145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwahk, K.-Y.; Park, D.-H. The effects of network sharing on knowledge-sharing activities and job performance in enterprise social media environments. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2016, 55, 826–839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaplan, A.M.; Haenlein, M. Users of the world, unite! The challenges and opportunities of Social Media. Bus. Horiz. 2010, 53, 59–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Saifi, S.A.; Al Saifi, S.A.; Dillon, S.; Dillon, S.; McQueen, R.; McQueen, R. The relationship between face to face social networks and knowledge sharing: An exploratory study of manufacturing firms. J. Knowl. Manag. 2016, 20, 308–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin SH, J.; Ma, J.; Johnson, R.E. When ethical leader behavior breaks bad: How ethical leader behavior can turn abusive via ego depletion and moral licensing. J. Appl. Psychol. 2016, 101, 815–825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, A.N.; Ali, A.; Khan, N.A.; Jehan, N. A study of relationship between transformational leadership and task performance: The role of social media and affective organizational commitment. Int. J. Bus. Inform. Syst. 2019, 31, 499–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loukis, E.; Charalabidis, Y.; Androutsopoulou, A. Promoting Open Innovation in the Public Sector through Social Media monitoring. Gov. Inf. Q. 2017, 34, 99–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fusi, F.; Feeney, M.K. Social media in the workplace information exchange, productivity, or waste? Am. Rev. Public Adm. 2018, 48, 395–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pee, L.; Lee, J. Intrinsically motivating employees’ online knowledge sharing: Understanding the effects of job design. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2015, 35, 679–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, J.; Li, Y.; Zhong, X.; Zhai, L. Why users contribute knowledge to online communities: An empirical study of an online social Q & A community. Inf. Manag. 2015, 52, 840–849. [Google Scholar]

- Eisenbeiss, S.A.; Brodbeck, F. Ethical and unethical Leadership: A cross-cultural and cross-sectoral analysis. J. Bus. Ethics 2014, 122, 343–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fraj, E.; Matute, J.; Melero, I. Environmental strategies and organizational competitiveness in the hotel industry: The role of learning and innovation as determinants of environmental success. Tour. Manag. 2015, 46, 30–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tims, M.; Derks, D.; Bakker, A.B. Job crafting and its relationships with person-job fit and meaningfulness: A three-wave study. J. Vocat. Behav. 2016, 92, 44–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slemp, G.; Kern, M.L.; Vella-Brodrick, D.A. Workplace well-being: The role of job crafting and autonomy support. Psychol. Well-Being 2015, 5, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Javed, B.; Bashir, S.; Rawwas, M.Y.; Arjoon, S. Islamic work ethic, innovative work behavior, and adaptive performance: The mediating mechanism and an interacting effect. Curr. Issues Tour. 2017, 20, 647–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amundsen, S.; Martinsen, Ø.L. Linking empowering leadership to job satisfaction, work effort, and creativity: The role of self-leadership and psychological empowerment. J. Leadership. Organ. Stud. 2015, 22, 304–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, V.; Singh, S. Leadership and creative performance behaviors in R&D laboratories examining the mediating role of justice perceptions. J. Leadership. Organ. Stud. 2015, 22, 21–36. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Z.; Wang, N. Knowledge sharing, innovation and firm performance. Expert Syst. Appl. 2012, 39, 8899–8908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diener, E.; Emmons, R.A.; Larsen, R.J.; Griffin, S. The Satisfaction With Life Scale. Journal of Personality Assessment 1985, 49, 71–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, W.Y.; Pauleen, D.J.; Zhang, T. How social media applications affect B2B communication and improve business performance in SMEs. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2016, 54, 4–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ringle CM Wende, S.; Becker, J.M. Smart PLS 3; Smart PLS: Bönningstedt, Germany, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J.F.; Hult GT, M.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. A Primer on Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM); SAGE: Thousand Oak, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Henseler Jörg Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. A new criterion for assessing discriminant validity in variance-based structural equation modeling. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2015, 43, 115–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avkiran, N.K. An In-Depth Discussion and Illustration of Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling in Health Care. Health Care Manag. Sci. 2018, 21, 401–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Evaluating Structural Equation Models with Unobservable Variables and Measurement Error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nitzl, C.; Roldán, J.L.; Cepeda-Carrión, G. Mediation analysis in partial least squares path modeling: Helping researchers discuss more sophisticated model. Ind. Manag. Data Syst. 2016, 116, 849–1864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, A.F. Beyond Baron and Kenny: Statistical mediation analysis in the new millennium. Commun. Monogr. 2009, 76, 408–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preacher, K.; Hayes, A.F. Asymptotic and resampling strategies for assessing and comparing indirect effects in multiple mediator models. Behav. Res. Methods 2008, 40, 879–891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Scale | No of Items | Source |

|---|---|---|

| Ethical leadership (T1) | 10 | Brown et al. [41] |

| Knowledge sharing (T3) | 13 | Wang and wang [80] |

| Subjective well-being (T2) | 5 | Diener et al. [81] |

| Social media (T2) | 9 | Wang et al. [82] |

| Latent Variable | Factor Loading | Cronbach’s Alpha | Composite Reliability | (AVE) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| EL | 0.78–0.80 | 0.82 | 0.823 | 0.563 |

| KS | 0.75–0.89 | 0.90 | 0.856 | 0.678 |

| SWB | 0.82–0.86 | 0.86 | 0.845 | 0.789 |

| SM | 0.85–0.90 | 0.89 | 0.867 | 0.756 |

| Fornell–Larcker Criterion | Heterotrait–Monotrait Ratio (HTMT) | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Constructs | EL | KS | SWB | SM | Constructs | EL | KS | SWB | SM |

| EL | 0.667 | EL | |||||||

| KS | 0.489 | 0.785 | KS | 0.587 | |||||

| SWB | 0.523 | 0.487 | 0.734 | SWB | 0.645 | 0.783 | |||

| SM | 0.467 | 0.568 | 0.556 | 0.793 | SM | 0.576 | 0.548 | 0.789 | |

| Effects on Endogenous Variables | Direct Effect | t-Value | Percentile Bootstrap 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|

| Subjective well-being (R2 = 0.50 /Q2 = 0.37) | |||

| Ethical leadership (a1) | 0.435*** | 10.632 | [0.156; 0.332] Sig. |

| Social media (R2 = 0.45/Q2 = 0.26) | |||

| Ethical leadership (a2) | 0.282*** | 5.673 | [0.252; 0.372] Sig. |

| Subjective well-being (a3) | 0.425*** | 6.728 | [0.192; 0.256] Sig. |

| Knowledge sharing (R2 = 0.48/Q2 = 0.32) | |||

| H1: Ethical leadership (c’) | 0.018ns | 0.278 | [0.042; 0.103] N.Sig. |

| Subjective well-being (b1) | 0.385*** | 5.672 | [0.148; 0.269] Sig. |

| Social media (b2) | 0.263*** | 4.529 | [0.267; 0.349] Sig. |

| Total effect of EL on KS (c) | Direct Effect of EL on KS | Indirect Effects of EL on KS | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coefficient | t Value | Coefficient | t Value | Point Estimate | Bootstrap 95% CI | ||

| 0.484 *** | 5.298 | H1:c’ | 0.018ns | 0.563 | Total(a1b1+a2b2+a1a3b2) | 0.48 | [0.178; 0.237] |

| H2: a1 b1 (via SWB) | 0.34 | [0.165; 0.338] | |||||

| H3: a2 b2 (via SM) | 0.28 | [0.145; 0.256] | |||||

| H4: a1 a3 b2 (via SWB + SM) | 0.23 | [0.186; 0.234] | |||||

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Hayat Bhatti, M.; Akram, U.; Hasnat Bhatti, M.; Rasool, H.; Su, X. Unraveling the Effects of Ethical Leadership on Knowledge Sharing: The Mediating Roles of Subjective Well-Being and Social Media in the Hotel Industry. Sustainability 2020, 12, 8333. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12208333

Hayat Bhatti M, Akram U, Hasnat Bhatti M, Rasool H, Su X. Unraveling the Effects of Ethical Leadership on Knowledge Sharing: The Mediating Roles of Subjective Well-Being and Social Media in the Hotel Industry. Sustainability. 2020; 12(20):8333. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12208333

Chicago/Turabian StyleHayat Bhatti, Misbah, Umair Akram, Muhammad Hasnat Bhatti, Hassan Rasool, and Xin Su. 2020. "Unraveling the Effects of Ethical Leadership on Knowledge Sharing: The Mediating Roles of Subjective Well-Being and Social Media in the Hotel Industry" Sustainability 12, no. 20: 8333. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12208333

APA StyleHayat Bhatti, M., Akram, U., Hasnat Bhatti, M., Rasool, H., & Su, X. (2020). Unraveling the Effects of Ethical Leadership on Knowledge Sharing: The Mediating Roles of Subjective Well-Being and Social Media in the Hotel Industry. Sustainability, 12(20), 8333. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12208333