Visiting Dark Murals: An Ethnographic Approach to the Sustainability of Heritage

Abstract

1. Introduction

“As the social process that gradually converts something of little or no interest in tourism into a resource with tourism potential. This is a social process where different social actors take part”.

2. Theoretical Framework

3. Literature Review

4. Materials and Methods

“Collect a variety of information from different perspectives and different sources. Use observation, open interviews, and site documentation, as well as audio-visual materials such as recordings and photographs. Write field notes that are descriptive and rich in detail. Represent participants in their own terms by using quotations and short stories. Capture participants’ views of their own experiences in their own words”.

- Do you think this is a controversial mural?

- Why do you think that not as many people visit this mural compared to Shoreditch street art, for example?

- In your opinion, what is the future of the mural?

- Do you think that the Tower Hamlets Borough is committed to its conservation?

- Do you think that the new ethnical groups (Bangladeshi) living in the area will also get involved?

- Do you think that the new economic groups (Highway) will also get involved?

5. Results

5.1. History behind the Battle of Cable Street Mural, London

“Several smaller council-housing projects, for 60–660 people each, had been completed, the first being Beachcroft Buildings off Cable Street, in 1894, which housed nearly 200 residents”.[64] (p. 186)

“Along both sides of the street you would have shops at the ground level. The first two-thirds or three-quarters of the street was almost entirely Jewish and the last third/quarter was Irish”.

“In the 1970s, the Bangladeshi immigrants started to come. This has always been an area of immigrants for 2000 years”.

“Trade union militants mobilised sweatshop workers—mostly Jewish—and dock and railway workers, many of whom were of Irish heritage”.[52] (p. 340)

“My dad, Sid Koenick, was at Cable St, he was 10 years old and was on a roof chucking slates at the blackshirts, he also told me about how they threw marbles under the hooves of the police horses, seven years later he lied about his age to join the airforce, he was sent to the Far East and took part in the mutiny that spread across all the forces at the end of the war. When he came back to the East End after being demobbed, walking with my grandparents, someone shouted anti-Semitic abuse at them and my dad knocked him out”.(Stella Koenick, Eastendwalks Facebook, 20 April 2018)

“Women, from their flats, picked everything in their kitchen to throw”.(D.R.)

“Certainly, the content of the mural is controversial because it is about the conflict between the forces of the far right and those who opposed them. It is also very much about anti-semitism. When I was restoring the mural—after it had been ‘paint-bombed’ by a far-right group—my car was vandalised and my life publicly threatened by Combat 88”.

5.2. Present and Opportunities

“Anti-fascists from far and wide continue to visit it”[64] (p. 361).

“It is a site of pilgrimage because of the significance of the ‘Battle of Cable Street’ in stopping the rise of Fascism in Britain before the war”.(P.B.)

“When in America there was a massacre in a Synagogue in Pittsburgh, Jewdas (a radical Jewish group) organised a 24-h concentration here”.(D.R.)

“I was assisted by a person of Bangladeshi origin when I restored it in 2011. I hope there continues to be support in the community for the mural—there certainly should be because the issues the mural refers to are relevant to all immigrant communities. The people who resisted Oswald Mosley were Irish, Asian, Jewish and many other ethnicities and nationalities”.(P.B.)

“The building at Brick Lane was first a Christian Church, then, in the beginning of the 19th century, a Jewish Synagogue and now is a Mosque”.

“This area is quite characterised by these extremes. It has extreme poverty and extreme wealth. And it is very old but also very modern. And that, I think, is part of the character of London actually”.(J.C.)

“The Councillors themselves are very supportive. There is a strong group of independents, among them you have Muslims. Conservatives are a small number”.(D.R.)

“When I was restoring it in 1996 and in 2011 there were many visitors from all over the world”.(P.B.)

“In Tower Hamlets I think this is the only guesthouse”.(J.C.)

“In a couple of years, Shoreditch will be as touristic as Camden”.

“I’m not a fan of dark tourism but I’m interested in political issues. I didn’t know the mural”.(North-American woman, 30 years old)

“We didn’t know the mural but we like both educative and creepy attractions”.(British couple, 25 years old)

“It does not seem worth taking transportation all the way to this place just to look at a wall painting”.(TripAdvisor comment)

“The library organises a book festival every year that could help memorialise it. The Council itself could organise tours”.(D.R.)

“Visitors mostly don’t know about the mural… But generally, people are quite interested in its history. We have also a certain amount of people from the Jewish diaspora coming from the USA and Israel who have family connections to East London. They visit where their ancestors lived… Other people are introduced to a different part of the city”.(J.C.)

“Maybe we could produce an exhibition about antifascism clashes around the country”.(D.R.)

“The [Jack Ripper] museum is visited by tourists all over the world, British families on holidays, school and university groups”.(local woman, 50 years old)

“Chinese tourists come in to explore the history of the Chinese Opium market at the end of the 19th century… And another part… is the visit of this area where the famous gangsters, the Kray twins, operated throughout the 1950s–60s”.(J.C.)

“What could affect the mural is what could happen with the building. I presume some social conservation will come around… the local community including the Bengalis are very proud of the mural…But the liveliest areas of the East End like Shoreditch are a long way from here. Now it is mainly residential but very accessible with the cycle route”.(D.R.)

“I believe there is huge support for the mural because of the reasons given above. I’m sure it will be preserved for many years. Tower Hamlets have been consistently involved in the conservation of the mural. I hope very much they continue to”.(P.B.)

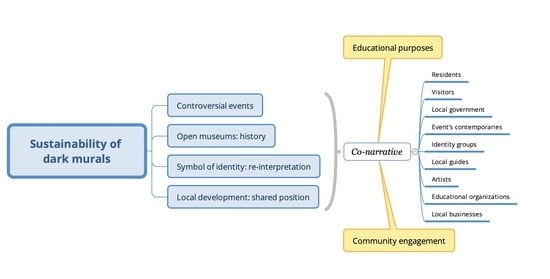

6. Discussion

7. Conclusions and Limitations

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kotler, N.G.; Kotler, J.R.; Kotler, W.I. Museum Marketing & Strategy: Designing Missions, Building Audiences, Generating Revenue and Resources; Jossey Bass: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Seaton, T. Patrimony, engineered remembrance and ancestral vampires: Appraising thanatouristic resources in Ireland and Sicily. In Dark Tourism; Hooper, G., Lennon, J., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, L.; Xu, J.B.; Sun, Z.; Xu, Y. Street Art as Alternative Attractions: A Case of the East Side Gallery. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2019, 29, 76–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNESCO. Culture for Sustainable Development. UNESCO. 2019. Available online: https://en.unesco.org/themes/culture-sustainable-development (accessed on 25 October 2019).

- Skinner, J. “On the face of it”: Wall-to-wall home ethnography. In Conservation, Tourism and Identity of Contemporary Community Art: A Case Study of Felipe Seade’s Mural “Allegory to Work”; Santamarina Campos, V., Carabal Montagud, M.A., de Miguel Molina, M., de Miguel-Molina, B., Eds.; Apple Academic Press, Taylor & Francis: New York, NY, USA, 2017; pp. 117–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prigoff, J.; Dunitz, R.J. Walls of Heritage, Walls of Pride: African American Murals; Pomegranate: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Latorre, G. Walls of Empowerment: Chicana/o Indigenist Murals of California; University of Texas Press: Austin, TX, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Theisen, O.J. Walls that Speak: The Murals of John Thomas Biggers; University of North Texas Press: Denton, TX, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Checa-Artasu, M. The walls speak: Mexican popular graphics as heritage. In Visiting Murals: Politics, Heritage and Identity; Jolliffe, L., Skinner, J., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2017; pp. 59–74. [Google Scholar]

- Neill, W.J. Marketing the urban experience: Reflections on the place of fear in the promotional strategies of Belfast, Detroit and Berlin. Urban. Stud. 2001, 38, 815–828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dartnell, M. Walls and Places: Political Murals in Belfast. Available online: http://web2.uwindsor.ca/courses/ps/dartnell/wallandplaces.html (accessed on 25 September 2019).

- Skinner, J.; Jolliffe, L. ‘Wall-to-wall coverage’: An introduction to murals tourism. In Visiting Murals: Politics, Heritage and Identity; Jolliffe, L., Skinner, J., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2017; pp. 3–24. [Google Scholar]

- Riggle, N.A. Street Art: The Transfiguration of the Commonplaces. J. Aesthet. Art Crit. 2010, 68, 243–257. [Google Scholar]

- Ross, J.I. Routledge Handbook of Graffiti and Street Art; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Campos, R.; Sequeira, A. Urban Art touristification: The case of Lisbon. Tourist Stud. 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Miguel Molina, M.; de Miguel Molina, B.; Santamarina Campos, V. Visiting African American murals: A content analysis of Los Angeles, California. J. Tour. Cult. Chang. 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pressenda, P.; Sturani, M.L. Open-air Museums and ecomuseums as tools for landscape management: Some Italian experience. In European Landscapes and Lifestyles: The Mediterranean and Beyond; Roca, Z., Ed.; Ediçoes Universitarias Lusofonas: Lisboa, Portugal, 2007; pp. 331–344. Available online: http://hdl.handle.net/2318/99914 (accessed on 15 September 2019).

- Merrill, S. Keeping it real? Subcultural graffiti, street art, heritage and authenticity. Int. J. Herit. Stud. 2015, 21, 369–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McAuliffe, C.; Iveson, K. Art and crime (and other things besides…): Conceptualising graffiti in the city. Geogr. Compass 2011, 5, 128–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dash, D. Mural Magic: Karl Schutz and Chemainus “The Little Town That Did”; Mural Magic Publications: Chemainus, BC, Canada, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Barnes, T.J.; Hayter, R. ‘The Little Town That Did’: Flexible Accumulation and Community Response in Chemainus, British Columbia. Reg. Stud. 1992, 26, 647–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bofkin, L. Concrete Canvas: How Street Art is Changing the Way Our Cities Look; Cassell Illustrated: London, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Grondeau, A.; Pondaven, F. Le street art, outil de valorisation territoriale et touristique: l’exemple de la Galeria de Arte Urbana de Lisbonne. EchoGéo 2018, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arandelovic, B. Creative City Berlin. In Public Art and Urban Memorials in Berlin; The Urban Book Series; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2018; Chapter 1. [Google Scholar]

- Arts Council England. Improving Places: Culture & Business Improvement District Partnerships. 2017. Available online: https://www.artscouncil.org.uk/publication/improving-places-culture-business-improvement-district-partnerships (accessed on 15 September 2019).

- De Miguel Molina, M.; Santamarina Campos, V.; De Miguel Molina, B.; Martínez Carazo, E.M. Balancing Uruguayan Identity and Sustainable Economic Development through Street Art. In Visiting Murals: Politics, Heritage and Identity; Jolliffe, L., Skinner, J., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2017; pp. 196–214. [Google Scholar]

- Saunders, A. Recovering the street: Relocalising urban geography. J. Geogr. Higher Educ. 2013, 37, 536–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Figini, P.; Vici, L. Off-season tourists and the cultural offer of a mass-tourism destination: The case of Rimini. Tour. Manag. 2012, 33, 825–839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arts Council. Arts audiences: Insight. 2011. Available online: https://www.artscouncil.org.uk/sites/default/files/download-file/arts_audience_insight_2011.pdf (accessed on 15 September 2019).

- Stone, P.R.; Hartmann, R.; Seaton, T.; Sharpley, R.; White, L. The Palgrave Handbook of Dark Tourism Studies; Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Light, D. Progress in dark tourism and thanatourism research: An uneasy relationship with heritage tourism. Tour. Manag. 2017, 61, 275–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, E. Educational dark tourism at the holocaust museum in Jerusalem. Ann. Tour. Res. 2011, 38, 193–209. Available online: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0160738310001040 (accessed on 20 September 2019). [CrossRef]

- Cohen, E. Thanatourism: A Comparative Approach. In The Palgrave Handbook of Dark Tourism Studies; Stone, P.R., Hartmann, R., Seaton, T., Sharpley, R., White, L., Eds.; Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK, 2018; pp. 157–171. [Google Scholar]

- Hooper, G.; Lennon, J. Dark Tourism; Routledge: London, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seaton, T. Guided by the dark: From thanatopsis to thanatourism. Int. J. Herit. Stud. 1996, 2, 234–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foley, M.; Lennon, J. JFK and dark tourism: A fascination with assassination. Int. J. Herit. Stud. 1996, 2, 198–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stone, P.R. A dark tourism spectrum: Towards a typology of death and macabre related tourist sites, attractions and exhibitions. Tour. Interdiscip. Int. J. 2006, 52, 145–160. Available online: https://hrcak.srce.hr/161464 (accessed on 20 September 2019).

- Raine, R. A dark tourist spectrum. Int. J. Cult. Tour. Hosp. Res. 2013, 7, 242–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blom, T. Morbid tourism: A postmodern market niche with an example from Althorp. Nor. J. Geogr. 2000, 54, 29–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Miguel Molina, M.; Barrera Gabaldón, J.L. Controversial heritage: The Valley of the Fallen. Int. J. Cult. Tour. Hosp. Res. 2019, 13, 128–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koster, R.L.P. Mural-based tourism as a strategy for rural community economic development. In Advances in Culture, Tourism and Hospitality Research; Woodside, A.G., Ed.; Emerald: Bingley, UK, 2008; Volume 2, pp. 153–292. [Google Scholar]

- Carden, S. The use and social enjoyment of murals: ‘the people’s art’, its publics and cultural heritage. In Conservation, Tourism and Identity of Contemporary Community Art; Santamarina Campos, V., Carabal Montagud, M.A., de Miguel Molina, M., de Miguel Molina, B., Eds.; Apple Academic Press: Abington, PA, USA, 2017; Chapter 13. [Google Scholar]

- Boyd, S.W. Post-conflict tourism development in Northern Ireland: Moving beyond murals and dark sites associated with its past. In Tourism and Hospitality in Conflict-Ridden Destinations; Isaac, R.K., Çakmak, E., Butler, R., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2019; pp. 226–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arandelovic, B.; Bogunovich, D. City profile: Berlin. Cities 2014, 37, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heidenry, R. The Murals of El Salvador: Reconstruction, Historical Memory and Whitewashing. Public Art Dialogue 2014, 4, 122–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karimi, P. Tourism, voyeurism and the media ecologies of Tehran’s mural arts. In Murals and Tourism: Heritage, Politics and Identity; Skinner, J., Jolliffe, L., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2017; pp. 75–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koensler, A.; Papa, C. Political tourism in the Israeli-Palestinian space. Anthropol. Today 2011, 27, 13–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McAtackney, L. Peace maintenance and political messages: The significance of walls during and after the Northern Irish ‘Troubles’. J. Soc. Archaeol. 2011, 11, 77–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crooke, E. The politics of community heritage: Motivations, authority and control. Int. J. Herit. Stud. 2010, 16, 16–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morris, P.; Arford, T. “Sweat a little water, sweat a little blood”: A spectacle of convict labor at an American amusement park. Crime Media Cult. 2019, 15, 423–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narvselius, E. Demonized, domesticated, virtualized: Fortification buildings as a case of Prussian heritage in present-day Kaliningrad. Natl. Pap. 2018, 46, 400–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murtagh, B.; Boland, P.; Shirlow, P. Contested heritages and cultural tourism. Int. J. Herit. Stud. 2017, 23, 506–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ong, C.E.; Minca, C.; Felder, M. The historic hotel as ‘quasi-freedom machine’: Negotiating utopian visions and dark histories at Amsterdam’s Lloyd Hotel and ‘cultural embassy’. J. Herit. Tour. 2015, 10, 167–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaw, W.M.K. In Situ: The contraindications of world heritage. Int. J. Islamic Archit. 2017, 6, 339–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frew, E.A. Interpretation of a sensitive heritage site: The Port Arthur Memorial Garden, Tasmania. Int. J. Herit. Stud. 2012, 18, 33–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Upton, A.; Schänzel, H.; Lück, M. Reflections of battlefield tourist experiences associated with Vietnam War sites: An analysis of travel blogs. J. Herit. Tour. 2018, 13, 197–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podoshen, J.S. Trajectories in Holocaust tourism. J. Herit. Tour. 2017, 12, 347–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yankholmes, A.; McKercher, B. Rethinking slavery heritage tourism. J. Herit. Tour. 2015, 10, 233–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koskinen-Koivisto, E.; Thomas, S. Lapland’s Dark Heritage: Responses to the Legacy of World War II. In Heritage in Action; Silverman, H., Waterton, E., Watson, S., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2017; pp. 121–133. [Google Scholar]

- Eriksson, P.; Kovalainen, A. Ethnographic research. In Introducing Qualitative Methods: Qualitative Methods in Business Research; Eriksson, P., Kovalainen, A., Eds.; SAGE Publications: London, UK, 2008; pp. 138–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mariampolski, H. Ethnography for Marketers: A Guide to Consumer Immersion; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Berg, B.L.; Lune, H. Qualitative Research Methods for the Social Sciences; Pearson Education: Cranbury, NJ, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Bernard, H.R. Social Research Methods: Qualitative and Quantitative Approaches; Sage Publications: London, UK, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Rosenberg, D. Rebel Footprints: A Guide to Uncovering London’s Radical History; Pluto Press: London, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Rosenberg, D. Battle for the East. End: Jewish Responses to Fascism in the 1930s; Five Leaves: London, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Mayor of London. Religion-Borough 2011–2018. Database Demography; 2018. Available online: https://data.london.gov.uk/dataset/percentage-population-religion-borough (accessed on 20 September 2019).

- Mills, R. Everything Happens in Cable St; Five Leaves Publications: Nottingham, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Rosenberg, D. An antidote to the far right’s poison’—The battle for Cable Street’s mural. The Guardian. 21 September 2016. Available online: https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2016/sep/21/battle-cable-street-mural-fascists-east-end (accessed on 27 September 2019).

- Facing History UK. Standing Up to Hatred on Cable Street. 2019. Available online: https://www.facinghistory.org/resource-library/standing-democracy/standing-hatred-cable-street (accessed on 5 September 2019).

- Tower Hamlets. Regeneration Delivery Plan; Tower Hamlets Transformation & Improvement Board: Tower Hamlets Borough, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- ONS. International Visitors to London. Office for National Statistics (ONS), International Passenger Survey. 2018. Available online: https://data.london.gov.uk/download/number-international-visitors-london/1eecf4ab-2636-4ebc-aaa7-f92517a3ed15/international-visitors-london.xls (accessed on 10 October 2019).

- De Miguel Molina, M.; de Miguel Molina, B.; Segarra Oña, M. Guidelines to stimulate use and social enjoyment. In Conservation, Tourism and Identity of Contemporary Community Art: A Case Study of Felipe Seade’s Mural “Allegory to Work”; Santamarina Campos, V., Carabal Montagud, M.A., de Miguel Molina, M., de Miguel Molina, B., Eds.; Apple Academic Press: New York, NY, USA, 2015; pp. 278–293. [Google Scholar]

- McCarthy, J. Regeneration of cultural quarters: Public art for place image or place identity? J. Urban Des. 2006, 11, 243–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yirik, S.; Seyitoğlu, F.; Çakar, K. From the white darkness to dark tourism: The case of Sarikamish. Int. J. Cult. Tour. Hosp. Res. 2016, 10, 245–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Segal, Y. The Battle of Cable Street. APT Films. 2006. Available online: https://vimeo.com/5817684 (accessed on 5 October 2019).

- Duffy, A. Trusting me, trusting you: Evaluating three forms of trust on an information-rich consumer review website. J. Consum. Behav. 2017, 16, 212–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brooke, M. Museum in Cable St about women and suffragettes turns out to be ‘Jack the Ripper’. The Docklands & East London Advertiser. 2018. Available online: https://www.eastlondonadvertiser.co.uk/news/heritage/museum-in-cable-st-about-women-and-suffragettes-turns-out-to-be-jack-the-ripper-1-4172863 (accessed on 20 September 2019).

- De Miguel Molina, M.; Skinner, J. Walls of Expression and Dark Murals Tourism. Anthropol. News 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strange, C.; Kempa, M. Shades of dark tourism: Alcatraz and Robben Island. Ann. Tour. Res. 2003, 30, 386–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, A. Negotiated consent or zero tolerance? Responding to graffiti and street art in Melbourne. City 2010, 14, 99–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

© 2020 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

de-Miguel-Molina, M. Visiting Dark Murals: An Ethnographic Approach to the Sustainability of Heritage. Sustainability 2020, 12, 677. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12020677

de-Miguel-Molina M. Visiting Dark Murals: An Ethnographic Approach to the Sustainability of Heritage. Sustainability. 2020; 12(2):677. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12020677

Chicago/Turabian Stylede-Miguel-Molina, María. 2020. "Visiting Dark Murals: An Ethnographic Approach to the Sustainability of Heritage" Sustainability 12, no. 2: 677. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12020677

APA Stylede-Miguel-Molina, M. (2020). Visiting Dark Murals: An Ethnographic Approach to the Sustainability of Heritage. Sustainability, 12(2), 677. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12020677