1. Introduction

Contemporary human society lies on the continuous flow of resources, information, and knowledge. However, despite the global interlinkage of human communities, most of these resources are concentrated in highly urbanized areas that keep relentlessly growing [

1]. Changes from natural and seminatural landscape into urbanized environments have shaped wide urban settlements, characterized by high population densities and large built areas [

2,

3,

4]. The dawn of the Fourth Industrial Revolution [

5] has reshaped the structure and functionality of the traditional types of urban settlements through the emergence of rural depopulation [

6], shrinkage of small and medium sized cities [

7], and sprawling pattern developments [

8,

9].

Resources, goods, jobs, or services are scattered throughout the territory and need to be accessible for population in exchange for a high effectiveness of urban settlements [

10]. Therefore, urban structure and form should provide appropriate ground for efficient mobility networks, allowing access to various types of resources. However, in the context of volatile planning system and procedures, the dynamic of urban structure and form can be unpredictable, affecting the mobility flows within [

11].

The constraint of access to the demanded and needed types of resources cause dissatisfaction among people, that usually lead to local, regional, or global conflicts. The occurrence of these type of conflicts are diminished or enhanced by territorial managers and local authorities, through planning strategies. Most of the conflicts arising within human settlements are rooted in the planning approaches or the lack of them [

12]. Whether we refer to conflicts generated by the association of incompatible functions [

13,

14,

15,

16], pollution effects [

17], nature conservation actions [

18], land ownership [

19,

20] or limited accessibility levels [

21], they are all directly or indirectly rooted in the planning systems.

In this study we bring into spotlight the conflicts induced by the design of the transportation network. Ganciu et al. [

22] emphasize that services distribution in a territory generates daily commuting flows, significantly influencing the territory’s development patterns, causing congestions and discomfort in large areas. Within the context of rapidly urban expansion, Zhao [

23] points out that a fundamental aspect of planning policies must take into account that urban growth management should be efficiently implemented to facilitate changes in the urban form for the sake of sustainable and qualitative transport networks’ development. Many studies have focused on the public transportation system, emphasizing how it can strongly contribute to the sustainability of urban settings [

10,

24]. The concerns regarding public transportation are relevant, as more urban environments are overcrowded, and distances are getting wider in terms of travel time [

25]. The shape, density and growth of a transportation network determine changes in property values [

26,

27,

28], exposure levels to air and noise pollution [

24,

29], accessibility degree to private or public services [

30,

31], or sprawling patterns [

21,

32]. Thus, the design of the mobility networks within human settlements can influence their livability levels, unfunctional networks conducting to public anger and eventually to planning-based conflicts.

Transportation efficiency is dependent on the settlement’s structure and shape. Policy makers have tried to establish the perfect mean of governance for the spreading urban settlements. Available land, as well as undisturbed environmental quality are vital assets for overcrowded cities [

11]. To reach these assets, metropolitan zones were set around major cities. The most common structure of a metropolitan zones consists of a polarizing city surrounded by polarized settlements, such as medium or small sized cities and rural areas [

3]. However, some metropolitan zones can expose polycentric patterns, where there are more than one polarizing urban core [

22]. In Europe, the term for such urbanized clusters was established by the European Union in collaboration with the OECD as metropolitan areas, represented by functional urban areas (FUA), consisting of a city with its commuting zone, counting a minimum of 250,000 inhabitants [

33]. The metropolitan structures are supposed to be based on symbiotic relations between the urban cores and the hinterland, in which each side provides the required resources for the other (e.g., jobs, higher quality services or access to the markets for the settlements in the hinterland and available land, improved environmental quality or leisure areas for the city core). The evolution and decay of human settlements have been always linked with the transportation networks, as most modern cities have flourished due to their position on strategic transportation routes. Therefore, metropolitan functionality is relying on the uninterrupted flux and exchanges between its components [

33,

34].

Through this study we aim to assess if the transportation planning strategies may lead to planning-based conflicts within metropolitan areas. In reaching our goal we have designed a methodological framework to help us assess the potential conflict occurrence due to transportation infrastructure planning in Romanian metropolitan areas. Within the methodological framework we proposed several tools for (1) analyzing the current situation of the metropolitan transportation networks; (2) assessing the level of collaboration between different actors from different levels for enhancing the accessibility towards private and public services; and (3) assessing the political stability degree within the metropolitan areas.

4. Discussion

The main outcome of our study consists of the proposed methodological framework used to determine the potential conflict occurrence generated by the mobility networks within metropolitan areas. Comparing with other methodological frameworks used to assess the transportation networks, the one proposed through this study has a modular characteristic, meaning that every single analysis tool can be extracted and integrated into other methodological approaches. The current study provides a quantitative analysis alternative to potential conflict assessments using qualitative and sociological methods [

44].

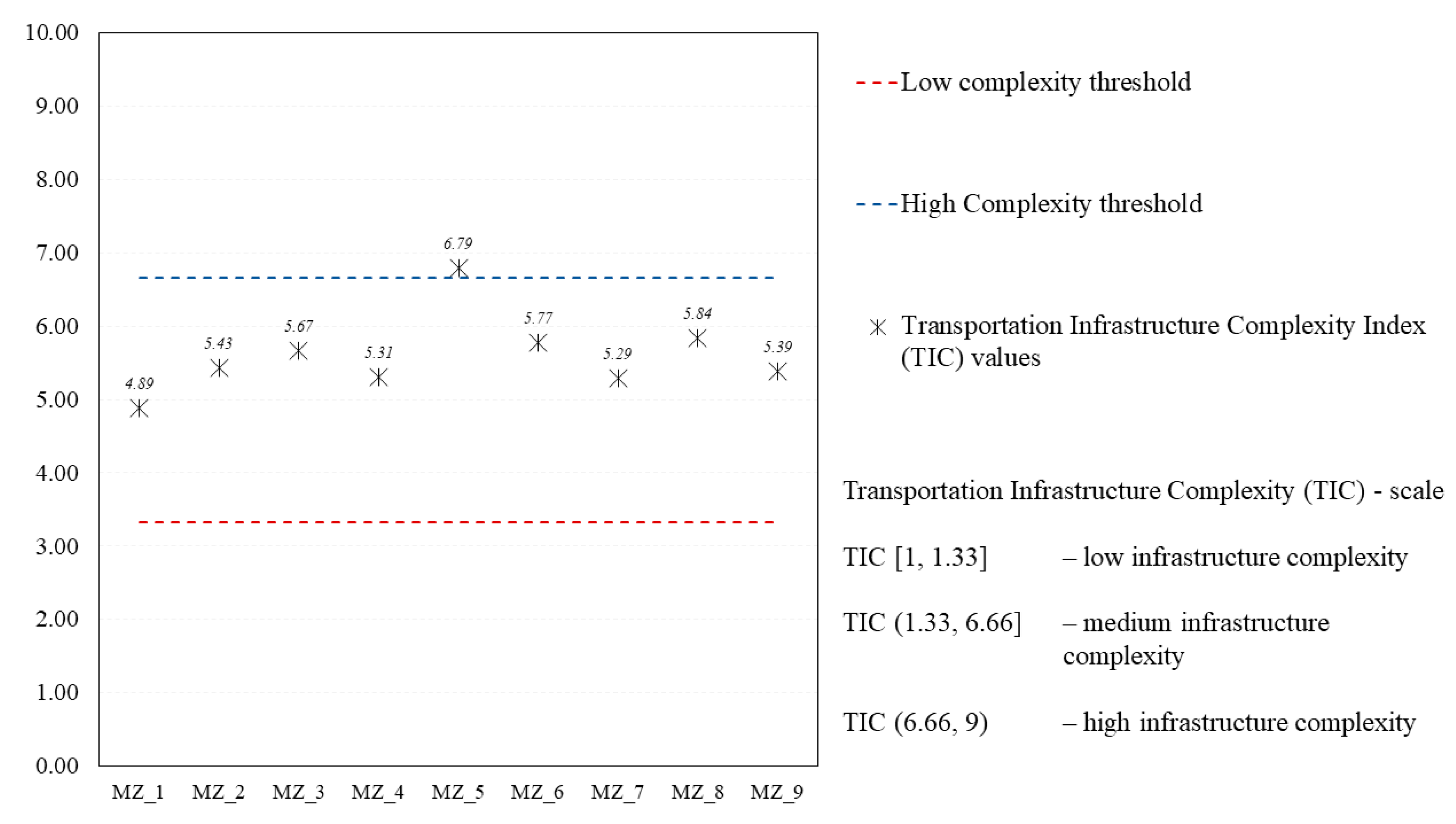

Transportation infrastructure complexity was assessed as multiple motion types provide alternatives in terms of speed or mean of travel for the users. However, a high complexity of transport infrastructure doesn’t imply an efficient mobility network design. Different types of transport infrastructure should be complementary, not exclusive for designing an effective network [

45]. Niță et al. [

46] conducted an assessment regarding the cycleways design in Bucharest concluding that it is not enough to design an infrastructure type, but it should also determine an increase of connectivity within the networks. This means that an effective planning of transportation networks should consider, besides infrastructure’s typology, what functions or structures it connects.

Studies focused on transport infrastructure rarely address the issue of complexity, being more interested in efficiency evaluation. However, for the Romanian situation the complexity of the transport infrastructure is a thorny subject as the European Commission has placed Romania last in the 2018 ranking of road quality and among the last three countries in the same years ranking regarding the efficiency of train services [

47]. Additionally, Bulai and Ursu [

48] emphasized that low road quality affects travel costs in Romania, while Shepherd and Wilson [

49] emphasized that the economies from Albania, Hungary, and Romania are strongly deprived of economic growth due to poor transportation networks. The low complexity of transportation infrastructure, especially the lack of motorways became the subject of national level conflicts, springing in February 2019 when a local businessman from the Romanian historical region of Moldova protested against the politicians that ruled the country since the fall of communism, as they had failed to initiate any project of motorway construction in this part of the country. The peculiar way of the businessman’s choice of protest, by constructing one meter of motorway using his own money launched a national protest movement under the slogan #ȘÎeu, which was rapidly spread through social media and transformed in a national protest against the Government in office at that time. National and foreign companies, as well as other politicians, including the President of the Republic manifested their support for the protesters [

50,

51]. Thus, as our results have showed, the analyzed metropolitan areas are characterized by an average complexity of transport infrastructure, but our assessment has not included quality indicators of the infrastructures. However, our results emphasize that, at least at metropolitan levels, the transportation infrastructures are not completely missing, and they need further refurbishment and development.

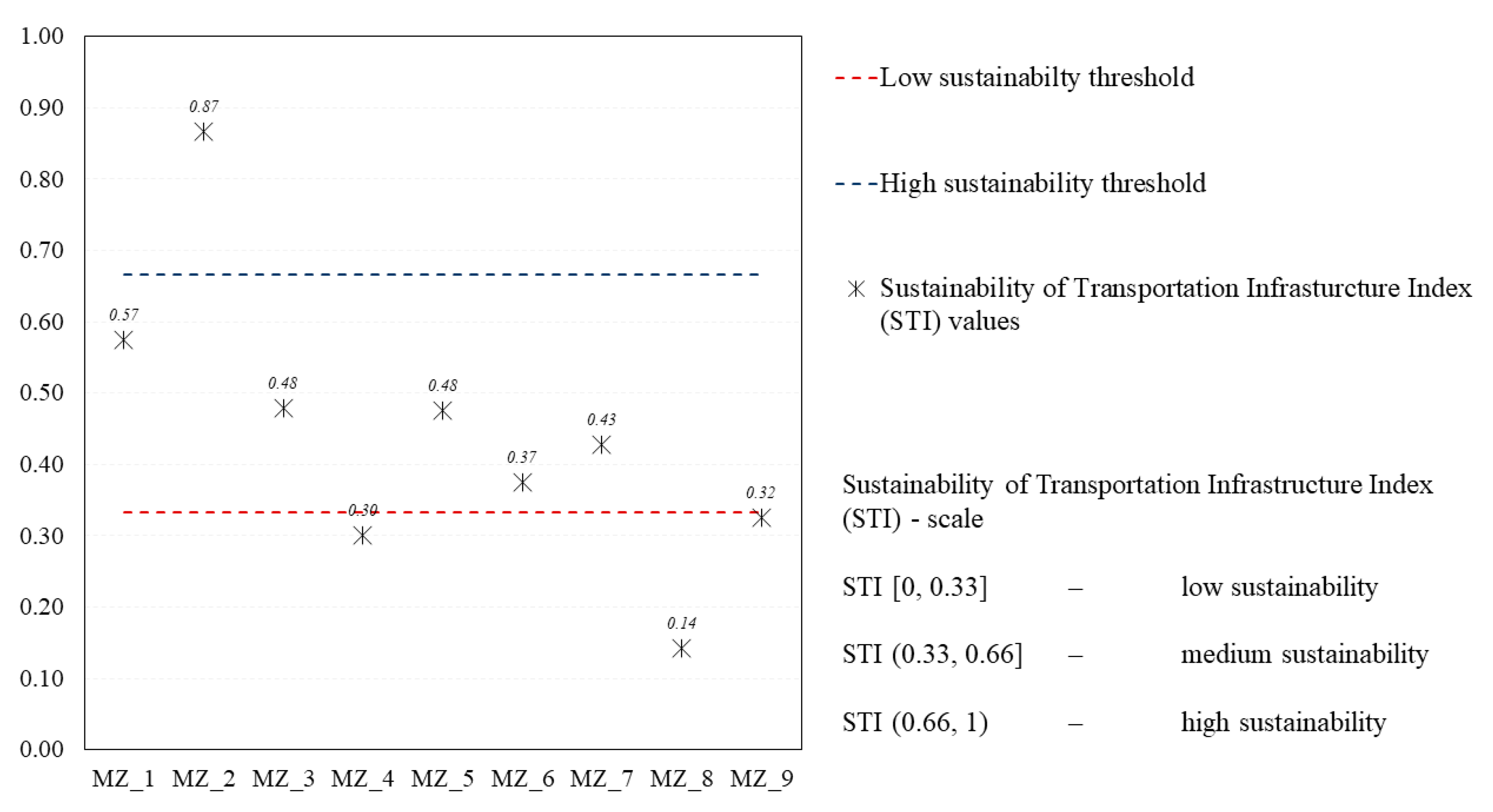

Studies of other researchers addressing the issue of mobility networks within urbanized settlements have analyzed the sustainability levels of the transport infrastructure. Kołoś and Taczanowski [

29] highlighted that the increasingly negative effects of car usage are fast creating a need for a means of public transport that is not only separated from street traffic, but that it is also effective and environmentally friendly, proposing light rail transportation as such an alternative. While developing our Sustainability Transport Infrastructure Index (STI) we considered railways and tramways as the most sustainable types of transport infrastructure and designed the formula to be able to emphasize the amount of these types of infrastructures within the metropolitan settlements. Besides a low environmental impact generated by the users of such infrastructure, Cloutier et al. [

52] state that alternative transportation can enhance the happiness levels of a community. Our results suggested that some Romanian metropolitan zones failed to record satisfying STI values, meaning that their residents are forced to use traditional means of transportation, which according to Cloutier et al. decrease the quality of life levels. This proved to be another useful tool to assess whether the metropolitan transportation network can represent a source of dissatisfaction, further generating potential conflicts. These assumptions are also endorsed by Alonso Raposo et al. [

53] and the European Commission [

54] by establishing their goals on developing a fully sustainable mobility network by decreasing the oil consumption for transportation at EU levels. If the current reality doesn’t change, then it can project a potential institutional conflict between EU and Romanian national bodies.

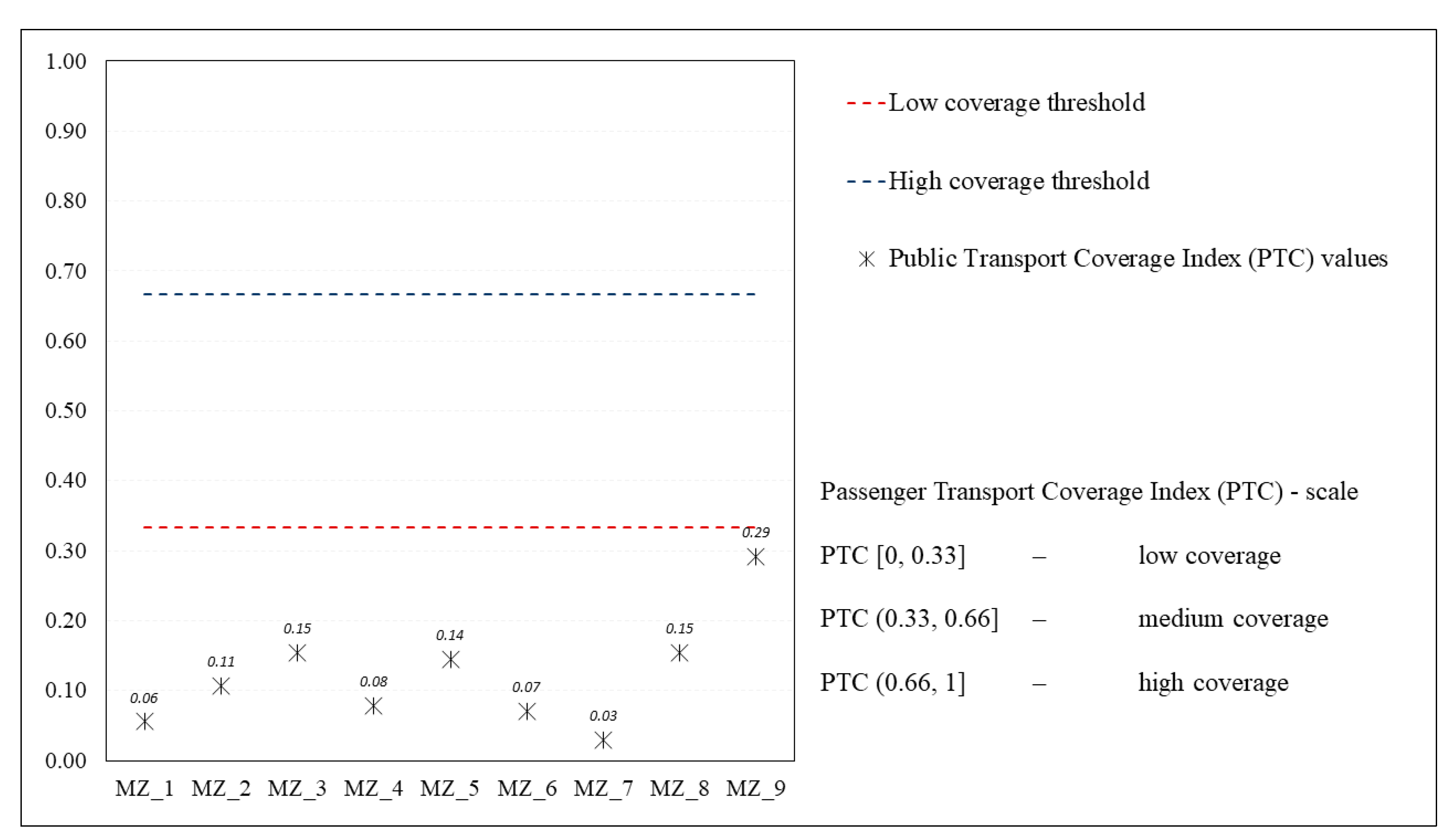

Public transportation coverage is a hot topic, covered by many research studies. Scholars have proposed various way for assessing the public transportation coverage, including data related to time distance [

55], accessibility towards public transportation [

10,

55] or accessibility of residential areas to roads [

56]. The Public Transportation Coverage Index (PTC) proposed in this study uses as input data the amount of metropolitan settlements included in the public transportation network and the density of the passenger transportation network within the metropolitan zones, which is in accordance with other similar approaches. More detailed calculations are hard to be compiled as the interurban passenger transportation system in Romania is exclusively private and there are a multitude of operators in this sector which makes it hard to access any statistics regarding the number of passengers, rush ours or precise timetables. Another shortcoming in developing more complex formulas to calculate the coverage of interurban passenger transportation is due to the fact that there are transportation operators which are not registered in any data base or online platform, thus are completely missing from the statistics, even though they operate as passenger transporters in field. By using the official data provided by the verified private passenger transporters, our results showed that there is at least one metropolitan settlement not covered by the passenger transport network. PTC results for all nine metropolitan zones were under the minimum coverage threshold. This means that all metropolitan zones being subject to our study have at least one administrative unit not being linked to the passenger transportation network. Thus, parts of the metropolitan population must drive their personal cars, walk, or hitchhike to reach the existing passenger transportation networks.

If we cross-check our results with the ones presented in the study of Man et al. [

57] regarding the accessibility of Romanian settlements towards the major urban areas, we should consider that the hinterland of the analyzed metropolitan zones is poorly connected to their urban core. Additionally, the passenger transportation network design for all nine metropolitan zones emphasize that, except the situation of MZ_9, all passengers from the settlements placed in the hinterland of the metropolitan zones have to pass through the urban core to reach other settlements within the same metropolitan zone.

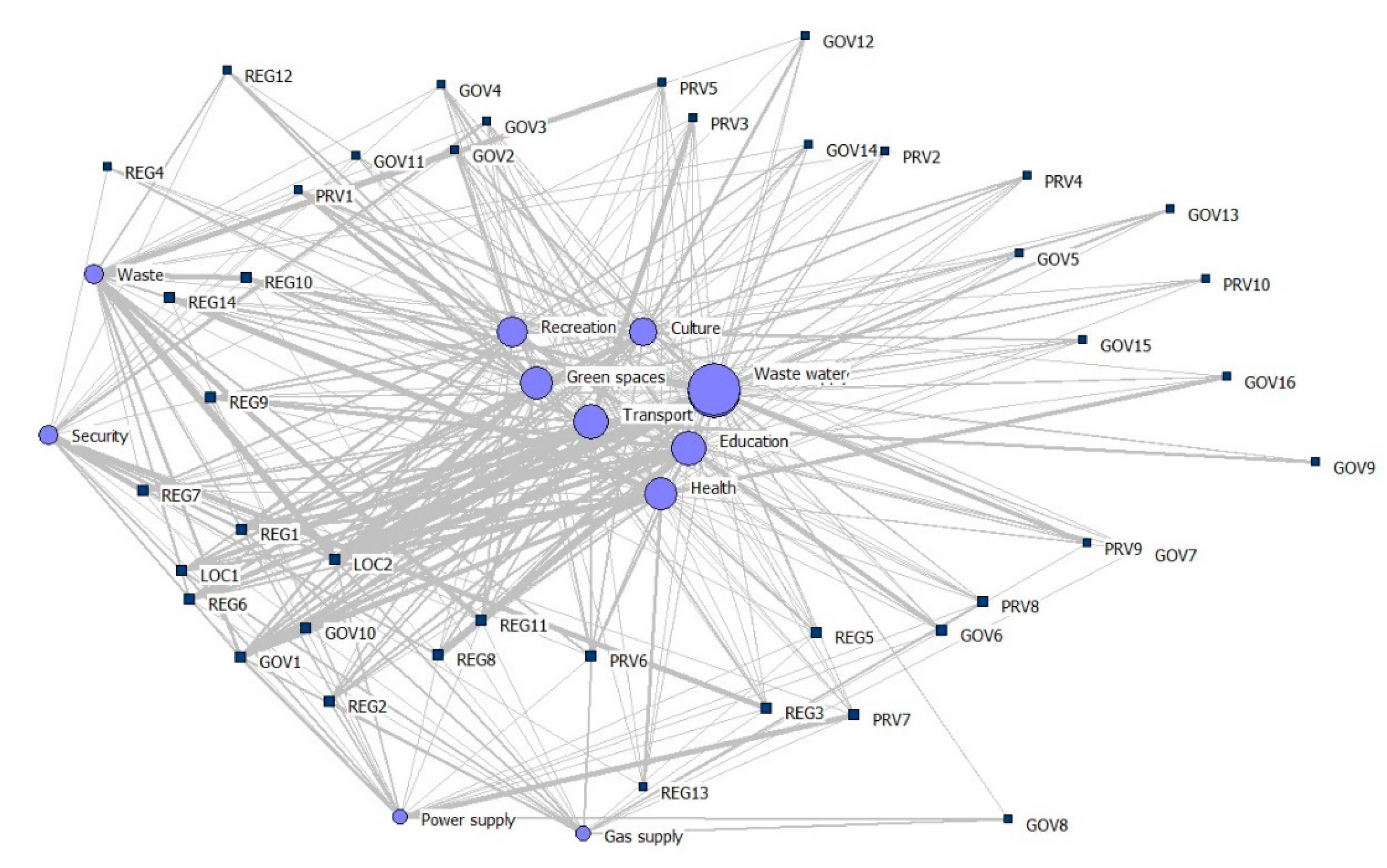

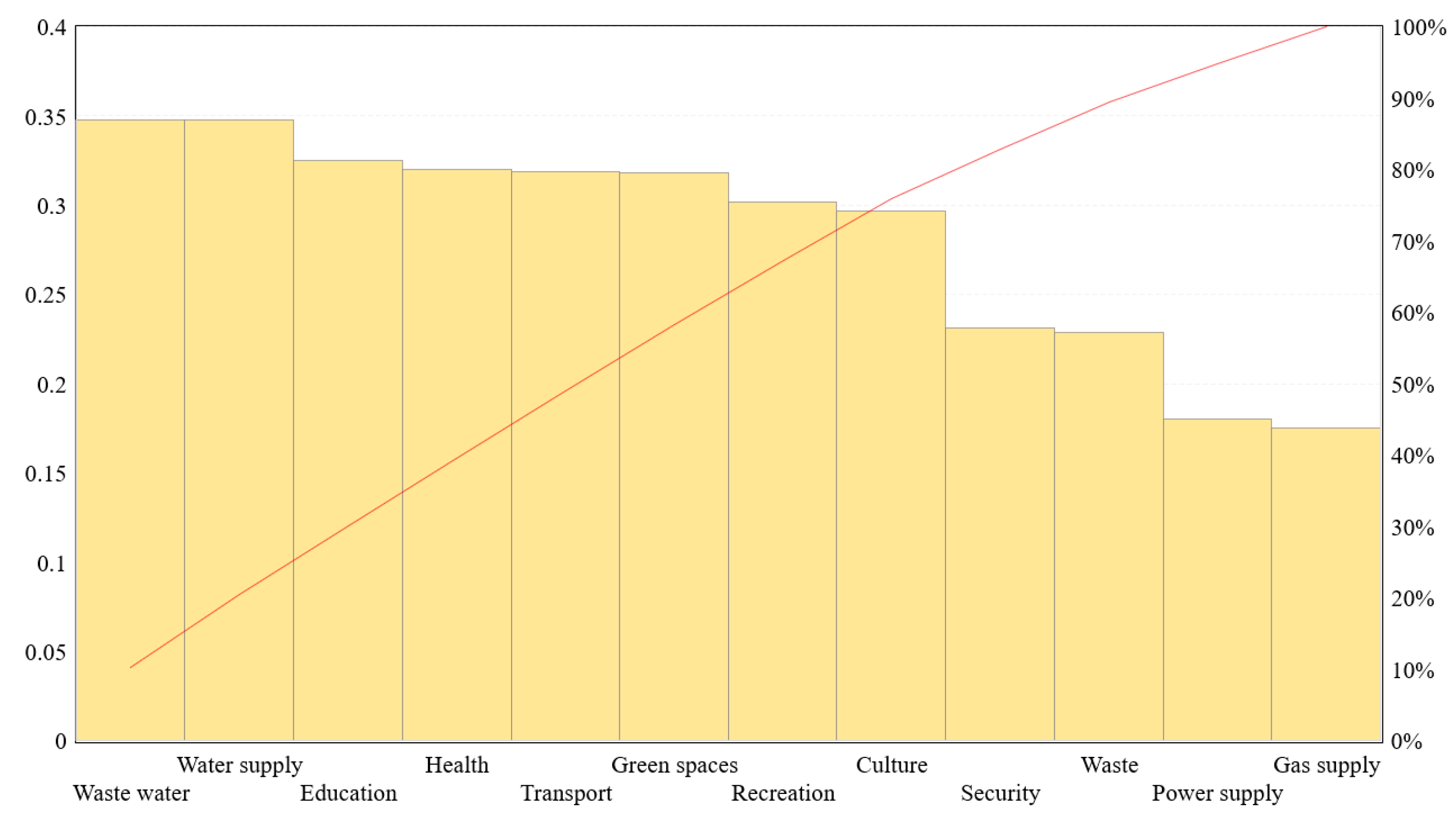

Assessments of the collaboration degree of different actors have proved to be a useful approach in analyzing the flows of knowledge in developing planning strategies and in the decision-making process. Social network analysis was used in various studies leading to valuable information about the governance of natural protected areas [

58,

59,

60] or urban settings [

61]. The network analysis used in our study revealed that enhancing the accessibility of metropolitan residents towards the transportation network is among the top priorities of different stakeholders and public institutions. These results are encouraging as the European authorities put a high price on mobility improvements at the EU level [

25,

54]. Angel and Blei [

62] emphasize that focusing on developing the mobility levels and shortening the commuting time within the metropolitan areas, by planning effective transportation networks will increase the productivity of the cities, otherwise the metropolitan areas are at risk to become unfunctional, determining a decrease in cities’ productivity and quality of life, as revealed by the study of García-Palomares [

63]. Thus, our results show that institutional and private stakeholders are working together to address the issue of mobility in the metropolitan zones, meaning that they acknowledge the importance of this issue.

Another important aspect of our analysis was whether the collaboration regarding metropolitan management and development is made using a decentralized or centralized approach. Researchers opinion differ on this subject based on the political system in which they professionally developed, and it is hard to provide an unbiased perspective over this subject. There are studies considering that a centralized approach of metropolitan management leads to malfunction as central authorities are not familiar with the specific issues occurring at regional level [

64] and there are studies emphasizing the benefits of centralized management of metropolitan zones, as the central Government has the overall picture of the territorial planning and can enhance further developments [

65]. We have opted to consider that a decentralized approach of metropolitan management is more suited for the Romanian context and the results have shown that there are stronger links of collaboration between local authorities and regional or private actors.

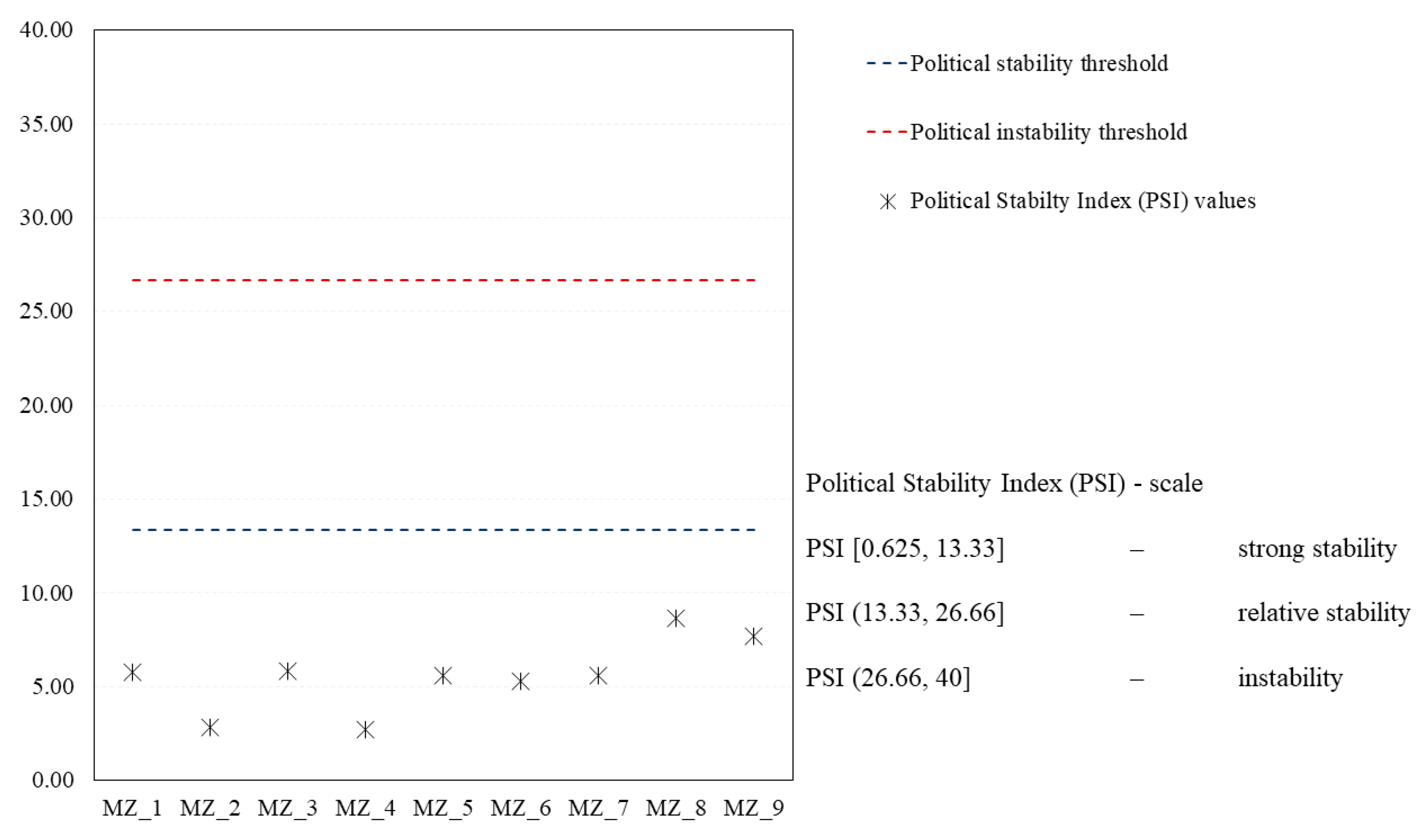

Although apparently not related with the metropolitan transport network design, political stability represents a driving force of development. Political influence over the metropolitan development is acknowledged by Vojnovic [

66] and this influence may adopt a sustainable approach or not, based on how rich the metropolitan areas are, as emphasized by the author. On the other hand, the study of Greasley et al. [

67] regarding the influence of local governing bodies over urban development contradicts the findings of Vojnovic and others, in which the local authorities play a significant role in establishing the urban planning direction. However, the authors concluded that their study is contradicting most of the researches, stating that this might be the situation for the British urban areas. Thus, if local politicians are important in metropolitan development, political instability can halt the progress of the region. Additionally, permanent changes of the community leaders reveal a high degree of unsatisfaction in regard with how the community is led. Our results show that all our case studies are characterized by high political stability rates, following the calculation of the Political Stability Index (PSI). This is also a positive result, as political turmoil can’t interfere in the process of the effective planning of metropolitan transportation network, high political stability being also an indicator of people’s agreement with the ways their communities are managed, preventing the manifestation of future conflicts.

There are several limitations of our methodological approach that need to be clarified in this study. The first one is related with the raw data used to develop the proposed indexes. We used data provided by public institutions or self-generated data using GIS techniques (e.g., the length of infrastructures in the metropolitan areas). Self-generated data may be sometimes subject to error occurrence. Romanian institutions managing transport infrastructures are not providing any GIS data to the public, thus we used a private database (OSM) to compile our results. As we have mentioned in the methods section we have cross-checked and refined this database with aerial imagery and official transportation maps to decrease the error levels, leading to misinterpretations. However, the level of accuracy of our indexes might not be perfect, but they can still provide an accurate image of the current state of the mobility networks within the metropolitan zones.

Another limitation of our study consists of the answer rate we have received for our survey regarding the collaboration between different actors on metropolitan issues. We have failed to reach the minimum target of 30%. However, we moved forward an presented the results as a methodological demonstration. Better answer rates are required for more accurate results, but our experience have once again emphasized the lack of dialog between the scientific community and the policy makers in Romania.