Abstract

Growing importance of sustainable development, corporate social responsibility and business ethics requires various types of contemporary organisations innovation. This research assesses the problem related to business policy innovation (BPI), which represents organisational governance determination. The main purpose of the paper is to qualitatively and quantitatively present a new, requisitely holistic strategic model of the soft factors influencing BPI, which interdependently incorporates changes in organisational values, culture and business ethics, as well as stakeholders’ interests reconciliation, thus determine soft possibilities for more sustainable business policy, management and practice. While the relevance of these factors for business policy is in the literature widely recognized, there is a small amount of empirical research on their influence on BPI. To mitigate this research gap, advanced structural equation modelling (SEM) based partial least squares (PLS) method was used for analysing data of 734 organisations in Slovenia, the EU state. The research results show that researched soft factors organisational values, culture and stakeholders’ interests reconciliation statistically confirmed influence BPI. Thus, these recognitions can be used as the basis for strategic managerial decision making towards social responsibility and sustainability of an organisation. Reasons why it has not been statistically confirmed that business ethics influence BPI needs to be investigated in future research.

Keywords:

business policy; governance; sustainability; values; culture; ethics; stakeholders’ interests; innovation; Slovenia 1. Introduction

As the subject of stringent requirements for contemporary organisations [1], corporate social responsibility and sustainability are getting the major consideration of organisations’ strategies [2] and there are many appeals to policy makers to increase efficiency and innovate their practice in this direction [3]. Due to the great significance of incorporation of social responsibility, business ethics, and sustainability principles in organisational practices, innovation of its business policy and management is needed. Top managers, who importantly influence organisational directions [4], should be developing and implementing strategies oriented towards greater social responsibility (SR) [5] and (humans’) requisite holism [6], for more business ethics and sustainability of the organisation. To achieve this, organisations must innovate their business policy/governance and consequently management and practice. Organisational governance, governed by organisational owners who determine business policy/governance orientation, is crucial for achieving social responsibility and business ethics. Namely, responsible determined business policy is realised through its fair, responsible (top, middle, first line) management and practice [7].

This implies the need for requisitely holistic scientific exploration of business policy innovation and research of those factors, which are more intangible (e.g., soft) but importantly influence the development of more sustainable business policy, thus also management and practice. Business policy, which represents organisational governance determination, presents broad defined general rules for the organisation development, which is realised through its management and business practice [7,8,9].

The importance of the organisational governance innovations and the resulting business policy innovation is illustrated by the fact that the future innovated business policy, i.e., its governance, management and practice, is under the influence of [9], (pp. 7–8):

- Intangible (e.g., soft) influential factors, e.g., existing organisation vision and business policy, and also soft variables—values and the resulting philosophy, culture, business ethics, norms, and interests, and

- Tangible influential factors, e.g., organisation strengths, weaknesses, opportunities and threats.

To achieve any innovation, thus also non-technological ones towards developing more sustainable business policy, management and practice, organisations have to be aware that, apart from the considered and not-considered intangible (e.g., soft) and tangible influential factors, there is also a part of them one has not noticed or do not have enough knowledge, time, money or other resources to know (the unknown part of these factors). The intangible (e.g., soft) influential factors are not easy to influence, at least not in the short term [10]. Additionally, they should be seen through the prism of requisitely holism and interdependency, which is rarely in the cited literature (Section 2 and Section 3), and in published papers not covered as well qualitatively as quantitatively yet. Most of the papers cited do not include a Systems Theory recognitions. They lack a requisitely holistic approach, which takes the interdependence of all important, but only important, viewpoints and their synergy into consideration.

Not many researchers qualitatively analysed and assessed the problem of business policy innovation (BPI) (See e.g., [5,10,11,12,13]) and they are not specific enough from the viewpoint of soft factors influencing BPI. Even rarer are quantitative researches on this theme [9]. Moreover, there are only a few studies which can confirm positive/negative impact of selected soft factors on business policy innovation (e.g., [14,15,16]), not offering enough holistic view of soft factors presented in this research. Particularly, there are no papers dedicated to comprehensive results qualitatively and quantitatively researching all the factors included in our research model. This paper diminishes the research gap in the area by analysing the importance of the inclusion of soft factors in making strategic decisions about BPI that can contribute to sustainable development of an organisation. Thus, it is ranked among economic dimension–economy-based sustainable development path towards sustainability. The content of the paper incorporates principles of Systems Thinking and should be understanding in synergy with other dimensions (sustainability paths), e.g. social, environmental, cultural, political, technological and other paths towards sustainability, which are dealing e.g., with affluence, population, transportation, energy, agriculture, ecosystems, etc.

The research problem addresses the question whether and to what extent organisational soft factors influence its business policy innovation. Accordingly, this paper tends to highlight the significance of the intangible, i.e., soft factors [10,17,18,19], in the literature recognised as important, but not in a synergy presented in this paper. Among them we requisitely holistic emphasise selected, that are in synergy interdependently influencing business policy innovation. The paper presents a new strategic model which interdependently [20] incorporates changes in organisational values, organisational culture and organisational business ethics, separately recognised as important and partially covered by [5,8,10,12,21,22], as well as key (owners/governors and top managers) and other stakeholders’ organisation’s interests’ reconciliation [11,23]. In the literature available to us such a requisitely holistic systems approach to the topic studied cannot be found. The aim is to demonstrate how researched soft factors influence business policy innovation and developing more sustainable business policy, management and practice. Therefore, empirical research has been conducted in order to reveal the views of owners and top managers regarding these soft factors and their influence on business policy innovation towards developing more sustainable business policy, management and practice. We analysed and discussed data gained from owners and top managers of 734 organisations in Slovenia, the EU state. The research results were gained with the structural equation modelling (SEM) based partial least squares (PLS) method using Smart PLS 3.2.8 [24] (see also [25,26,27,28,29] for details) and show which factors statistically confirmed influence business policy innovation and can be used as the basis for more holistic strategic managerial decision making [8,13,21,22] towards more social responsibility and business ethics for developing more sustainable business policy, management and practice.

The paper contributes to the development of the theory of integral management of organisations in the field of soft factors influencing business policy innovation (BPI), thus management and practice, towards the possibility of developing a more sustainable business policy. From the perspective of sustainability theory, the paper is limited to the social responsibility of organisations, which can be gained through business ethics and other requisite holistic selected soft factors included into the research model developed in this paper. We assume that organisations need to assure profit for their survival, thus this aspect is not part of our research and represent an important limitation. We also assume that organisations that are socially responsible enough are aware that the entire planet Earth needs to be taken care of as well, so this is our second important limitation.

Based on the theoretical research model developed we introduce the first quantitative survey with some very interesting research results. We note that the organisations studied are aware of the importance of diversity of values of different key stakeholders. In addition, with a proper culture they coordinate different interests. Statistically, we can confirm that these are factors that are included in the developed theoretical model and that affect BPI. However, it cannot be said that the 734 organisations we examined are aware of the importance of business ethics and their credibility, as the factor “ethics” is not important to them (although statistically not significant), and their performance is not high in this respect (only 40.271%). Therefore, it is important recognition of this research that despite of the general awareness of economic policy makers and researchers and also many publications on the subject in practice an awareness of the importance of business ethics, thus also social responsibility, still should be built and upgraded. Therefore, in the conclusion of this section, we highlight important recommendations for both owners, governors and managers, as well as for economic policy makers.

The paper includes theoretical backgrounds (Section 2), research model main hypothesis and other hypotheses developed (Section 3), methodology explanation (Section 4), research results and analysis presentation (Section 5), research results and analysis discussion (Section 6) and conclusions with practical applications of the research results and further research development recommendations (Section 7).

2. Theoretical Background

Numerous requirements towards integral governance and management models can be observed in the literature (e.g., [8,13,30]), which take into account those findings that seem more relevant to the authors of the model. MER-model (MER is the acronym: Management, Entwicklung and Research) is developed relying on the recognitions of the St. Gallen model of integral management (e.g., [30]), which is among the most well known in academic and professional communities. MER-model of integral governance and management is based on a multidimensional consolidation of organisational governance and its’ management with an organisation (internal environment) and its (external) environment, thereby taking into deliberation an organisation’s basic purpose of surviving and developing. Moreover, the MER-model is grounded on the presumption of the requisite objective, time and space integration of governance and management [22].

According to the MER-model [8] (p. 13) owners’ governance directions of an organisation directly result in business policy, which is accomplished on the strategic management level (thus business policy directly influences management strategic decisions) and indirectly realised on the operational management level and in business practice (i.e., in basic realisation process). Business policy defines the elementary, global and semi-permanent features of an organisation’ existence. It includes vision, mission, purposes and strategic goals of an organisation. Business policy has its roots in a vision, which is then incorporated into the business policy and implemented in the management processes: directly at the level of strategic management (with top management decisions) and indirectly at the level of operational management (with decisions of middle and first-line managers). Business policy is developed by key stakeholders expressing support for the implementation of general quantitative and qualitative changes needed in an organisation in order to ensure more sustainable development, survival, management and business practice, hence functioning in the long term [22], also all stakeholder’s interests are fulfilled. Refs. [8,21,22,23], and [13] emphasise that organisation’s system of values, culture and business ethics, as well as owners/governors and top managers—key stakeholders’ interests balancing influence the organisation’s business policy orientation towards more (or less) sustainability. In this paper it has been assumed that changes in the researched soft factors influence business policy innovation. We consider innovation as Mulej et al. [20] (p. 256)—as any in practice beneficial problem solving technological or non-technological novelty (see also [31], p. 1545). Mulej and Ženko [32] detected that non-technological innovations create preconditions for the technological ones [33].

As a non-technological innovation, business policy innovation is influenced by various factors (e.g., [13,23,30,34]; presented without extra emphasises of their synergy). These are (1) the analysis of (external) environment and markets with opportunities and threats specification; (2) the examination of the organisation (i.e., internal environment) with strengths and weaknesses specification; (3) the system of organisation’s values, culture and business ethics examination; (4) the interests of owners/governors and top managers, i.e., organisation’s key stakeholders and other stakeholders’ interests. All mentioned information form the basis for business policy innovation. Planning of business policy is affected by the existing organisation’s vision and business policy, values, culture, business ethics, norms and the related key (and other) stakeholders interests, as well as by organisation’s (internal) strengths and weaknesses, and (external) opportunities and threats [10]. This paper is focused on selected soft factors and their impact on more sustainable business policy, thus management and business practice.

Theoretical backgrounds basis for the new model proposal is MER-model of integral management [8,22,23]. Model design concerning the soft influencing factors of business policy innovation with explanation of the content of the factors and the items used for tested the hypotheses is in-depth presented in Appendix A. The soft factors were subjectively selected from MER-model of integral management recognitions in accordance with Dialectical Systems Theory [20], taking the expert knowledge of the authors into consideration. This is an appropriate method given that Systems Theory is also behind Sustainability theory. Their content was appropriately adapted to the findings of other researches and the authors’ own subjective professional background. The selected soft factors are organisational values, culture, business ethics and stakeholders’ interests.

The first of the researched selected soft factors is the factor organisational values. The term organisational values is often vague/ambiguous and there are various statements related to this term, such as espoused value, principle or stated values (See for details e.g., [35,36,37,38]), as well as core values (See for details e.g., [39,40,41]). Core values are related to some convergence linking actual behaviour with the declared believing [42], thus offer to organisations the opportunity to build more social responsibility, business ethics and sustainable values. Lencioni [39] (pp. 114–115) defined the core values as an intensely rooted fundamental truth that guides organisation’s development [defined with business policy; N.B. authors], management and business practice. Core values should be deeply authentic and are often influenced with the values of key organisation’s stakeholders, e.g., founders, therefore affect their decision on more or less sustainable business policy. In the MER-model, organisation’s (core) values are analysed based on Ulrich’s [21] recognitions and were, in this research, innovated based on Štrukelj recognitions [9].

The second of the researched selected soft factors is the factor organisational culture. Organisational culture points out a set of basic beliefs, is grounded on values and results in business ethics and norms within the organisation [9,43]. Therefore, members of the same organisation similarly understand the reality and take similar measures [44] (p. 26). Organisational culture generally refers to life and work in the organisation. While making decisions about business policy innovation, owners/governors need to take into consideration the system of values, shared ideologies, symbols and concepts that have developed in an organisation and shape its behaviour. If a person’s cultural values, which are passed from old generation to young generation, encourage characteristics such as social responsibility and business ethics, then this person is more likely to act in this way. Expressed differently, organisational culture might direct strategic decision-making towards sustainability oriented business policy, management and practice [44] (p. 27). In accordance with Hogan and Coote [45], the authors state that an innovation-oriented culture should direct organisation’s behaviour towards social responsibility, business ethics and sustainability.

The third of the researched selected soft factors is the factor organisational ethics. Issues of business ethics have become crucial for business policy innovation in order to provide organisations with a good reputation [46], although nowadays responsible and sustainable goals are in forefront. Business ethics should be incorporated in the organisation’ business policy and strategies in order to enhance the trust of stakeholders, which results in improved performance (different viewpoints to confirm that can be found in e.g., [47,48,49,50]), thus more social responsibility and sustainable management and practice. Organisational ethics refers to the principles and standards that guide behaviour of organisations, which must balance an owners’ desire to maximise profits against the needs of other stakeholders. Under such conditions, decision-makers must gain high ethical competences when dealing with notable moral problems that may arise in organisational activities [51]. Business ethics guides the organisations’ members to focus on the long-term oriented goals towards sustainable development of the community residents and sustainable growth of the organisation [52]. Incorporating business ethics and social responsibility in strategic management and strategies would enable the organisations such sustainable orientation [53]. As a part of innovating the humans’ values, social responsibility should be understood as “one’s responsibility for one’s impacts on society” and “creation and transfer of socially beneficial ideas, knowledge and inventions that consider interdependence in business and social environments” [33].

The fourth of the researched selected soft factors is the factor stakeholder’s interests. In order to innovate themselves in direction of sustainability, organisations should take all stakeholders interests into consideration [46]. Organisations can be viewed as an integration of stakeholders based on their interests. It generates a system synergy oriented toward the fulfilment of stakeholders’ interests. Organisation is a part of its environment and is actively involved in this environment [22]. Accordingly, (key) stakeholders’ interests were selected as criteria of business policy influence assessment [9]. A stakeholder in an organisation is “any group or individual who can affect or is affected by the achievement of the organisation’s objectives” [54]. Some stakeholders, such as employees and customers are critical for organisational survival, as they provide the organisation with essential resources [55].

The stakeholder theory calls our attention to a redefinition of the agency concept “by replacing the state that managers have a duty to stockholders with the concept that managers bear a fiduciary relationship to stakeholders” [56] (p. 17). Basic assumption of this theory is reflected in the view that organisation governance should be directed towards fulfilling interests of all stakeholders, not only towards owners’ interests [57]. Establishing effective relations with all stakeholders should be in the forefront [58]. Stakeholder theory provides a pragmatic approach to formulating responsible and sustainable business policy that will enable all relevant stakeholders to achieve long-term strategic goals through different developmental policies and actions. Achieving strategic goals and long-term success should be seen as a process for protecting the interests of all, not only key stakeholders. In a broader sense, this behaviour contributes to social responsibility [59], business ethics and more sustainability, therefore organisation’s success. Such behaviour “postulates the engagement of an organisation with stakeholders rather than shareholders alone” which is derived from the stakeholder model [56] (p. 8). The perceived dishonest, unethical or socially irresponsible organisational behaviour can diminish organisation’s good name, increase costs and diminish organisation’s shareholder value. In opposition to that, ethical or socially responsible organisational behaviour can fetch back significant benefits through the creating competitive advantages [60]. From stakeholders’ point of view, organisations should focus is on the social aspect, which refers to the capacity of ethically and responsible sustainable business policy to respond to the interests of different stakeholders, not only key one [5,7]. Respecting the so far researched, the resulting thesis reads: business policy can be improved with corporate social responsibility, business ethics and orientation towards sustainability. Therefore, the view of corporate social responsibility and business ethics as organisational activities directed towards all stakeholders’ interests, also linking corporate social responsibility and business ethics to sustainable development. Stakeholder theory is one of the most significantly used approaches in social, environmental and sustainability [governance and; N.B. authors] management research [16] and thus we incorporated it into our research. At this point, it is also necessary to draw attention to the many dangers of dispersal of responsibilities [61] as well as on an ethical dilemma caused with the independence of managers [62], which both should be taken into detailed consideration.

We propose to incorporate the presented theoretical roots per each one of the four soft factors identified into the MER-model of integral management. The MER-model draws attention to various factors that influence the development of an organisation (i.e., business policy, strategies and tactics), but does not emphasise their interdependence nor the effects of their synergies. The research model used in this paper incorporates those factors that, given the authors’ expertise, requisitely holistic and interdependently include soft viewpoints which, in synergy, can contribute to the development of more sustainable business policy, management and practice.

According to our recognitions, also the Theory of Sustainability should be developed towards greater integration of the studied soft factors into the existing framework. Namely, the theory of social responsibility as part of the sustainability theory emphasises the importance of interdependence and holism, but both can only be achieved if we have the right values, behave appropriately (have the right culture), know how to adapt our interests to long-term development and respect ethics. These lessons need to be further intensified in the development and operation of individuals, organisations and society. Only in this way will our behaviour meet the critical requirements that are necessary to preserve our planet and survival of live species, may it be from the viewpoint of coexisting of humans with biosphere, balanced environment (e.g., resources exploitation, investment and technological orientation), organisational change or other viewpoint. Notwithstanding the awareness of many individuals, collective awareness in this field is not yet sufficiently developed. Therefore, we propose to integrate the contents of this paper in synergy into the theory of sustainability.

Research model, main hypothesis and other hypotheses development are introduced in Section 3. The content is then followed by a presentation of methodology, research results and analysis, discussion and conclusion.

3. Research Model, Main Hypothesis and Other Hypotheses

This paper presents the outcomes of an empirical research executed among SMEs in Slovenia, the EU state. Since business policy has an influence on its management and practice [7,12,23], it is important to examine the factors which have an influence on business policy. Malik [11], Štrukelj and Šuligoj [10] and Štrukelj and Sternad Zabukovšek [63] emphasise the importance of analysing organisational values, culture, business ethics and stakeholders’ interests for business policy. They advocate that these factors have an influence on business policy innovation (BPI). Malik [11] and Štrukelj and Šuligoj [10] introduced qualitative research. Štrukelj and Sternad Zabukovšek [63] in-depth introduced quantitative research, but only from the aspect of organisation values and organisation business policy interdependence. This is why this research aim has been to demonstrate whether and to what extent these requisitely holistic selected soft factors influence business policy innovation thus developing more sustainable business policy, management and practice. The paper presents new strategic model of soft factors influencing business policy innovation, which interdependently incorporates changes in organisational values, culture and business ethics (which advocates also social responsibility), as well as organisation’s stakeholders’ interests reconciliation. Accordingly, the main research hypothesis (H1) of this paper reads:

Hypothesis 1 (H1).

Soft factors influence business policy innovation (BPI).

Based on the theory review researched soft factors have been requisitely holistic selected, taking their interdependence into account, like suggested Mulej et al. [20]. Influence of the following researched soft factors on business policy innovation (thus influencing development of more sustainable business policy, management and practice) has been taken into consideration: organisational values, culture and business ethics, as well as stakeholder’s interests. Based on this, four hypotheses were developed.

Organisational values help owners, managers and employees make decisions regarding how to act and react. They are treated as a guideline, which guidance the behaviour towards really important subjects [64] (p. 32), e.g., business ethics, social responsibility or sustainability. They serve as the organisational internal compass. The importance of organisational values for business policy development and innovation is widely recognized [65,66,67], yet not in synergy with other in this research selected soft factors. Towards sustainability oriented values could encourage better practice [65,68] and help incorporating of business ethics and social objectives into business policy [69]. In addition, values serve as guiding principles of vision and business policy [70]. Therefore, the core organisational values are very important [12,71] and owners and managers should hold them in their consciousness when developing more sustainable business policy, thus management and practice. Accordingly, and taking Štrukelj and Sternad Zabukovšek [63] recognitions into consideration, one can assume that organisational values have a positive and direct effect on business policy innovation (BPI)—hypothesis 1a (H1a).

Hypothesis 1a (H1a).

Organisational values have positive and direct effect on business policy innovation (BPI).

Researcher do not agree concerning the question regarding the type of organisational culture, which encourages innovation. Only few quantitative studies confirm positive influence of organisational culture on its innovativeness [72], yet not in synergy with other in this research selected soft factors. Although generally speaking, organisational culture affects organisational innovation [43] and the researches linked to the influence of organisational culture on divergent outcomes are substantial [73], yet, the quantitative research about the impact of organisational culture on innovation is relatively limited [74] and not showing the interdependence with business policy innovation. By emphasizing trustworthy values and norms, owners and managers can create an organisational culture that direct behaviour towards business policy innovation requirements [75], e.g., more social responsibility, business ethics and sustainability. Cultural dimension is undoubtedly linked to organisational strategy and performance [76] and must be derived from requirements in business policy. It is an important aspect that relates to creating an environment that should carefully consider current business policy and might take care for the future sustainability of the organisation. Janićijević [77] has also shown that there is a theoretical basis for the assumption that organisational culture is one of the factors in selection of organisational change management strategies, which the developing of more sustainable business policy, management and practice undoubtedly is. According so far researched, it is possible to hypothesize that organisational culture has a positive and direct effect on business policy innovation (BPI)—hypothesis 1b (H1b).

Hypothesis 1b (H1b).

Organisational culture has positive and direct effect on business policy innovation (BPI).

With increasing awareness of the importance of ethical issues, owners and managers must guide their organisations towards using ethical standards [53,78,79]. As part of the integral management model scholars have thoroughly investigated issues of business ethics in different forms, such as safety problems of products and services, agency problems, environmental violations, options backdating, workers mistreatment and securities protection fraud (e.g., [80,81,82]), which shows a lack of requisitely holism in organisations practice. Researching the investors’ perceptions of CEO succession selection, Connely et al. [83] indicated that ethical issues directly influence investors’ confidence. Actually, they concluded that investors are likely to replace the CEO who is related to some unethical behaviour. Increasing importance of corporate social responsibility [5,13,73] also favours the inclusion of ethical aspects in the definition of organisational business policy and strategy [9,47,48,49], thus governance, management and resulting practice to an organisation be more sustainable. As a part of organisational business policy and strategy orientation, corporate social responsibility helps in building organisational image as socially, ecologically, and environmentally responsible organisation and contributes to organisational change [10,49] towards sustainability. Thus, one can assume that organisational ethics has positive and direct effect on business policy innovation (BPI)—Hypothesis 1c (H1c).

Hypothesis 1c (H1c).

Organisational ethics has positive and direct effect on business policy innovation (BPI).

According to stakeholder theory, owners, when determining business policy, should not consider only their own interests but also interests of other stakeholders if an organisation is to succeed in a long-term time [57,59]. Incorporating a variety of stakeholders’ interests in policymaking processes, i.e., developing more sustainable business policy, can lead to more legitimate and widely supported policies [84]. Taking into account the growing importance of corporate social responsibility, many organisations develop strategic corporate responsibility plans and implement socially responsible, ethical and sustainable initiatives through business policy [11,12], consequently management and practice. Accordingly, the researchers suggest that divergent stakeholders’ interests can be managed [9] and that this process should help increasing the effectiveness of corporate social responsibility policies for the benefit of both organisations and society [15,85], thus achieving e.g., business ethics or sustainability. By using a case study method, Cummings et al. [86] show how managers consider internal and external pressures when formulating and implementing a new strategy and conclude that these interests have direct influence on strategy change, as can be expected, therefore more likely also those that meet the sustainability requirements. Accordingly, it can be assumed that stakeholders’ interests have positive and direct effect on business policy innovation (BPI). Therefore, hypothesis 1d (H1d) follows.

Hypothesis 1d (H1d).

Stakeholders’ interests have a positive and direct effect on business policy innovation (BPI).

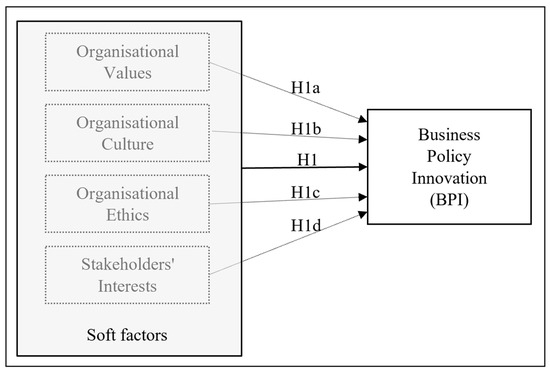

According to authors’ information, no research about this matter of question has been executed using this kind of mode to date. As a result, authors developed a research model (Figure 1), which incorporates the described hypotheses.

Figure 1.

Conceptual research model.

To research all selected soft factors, the questionnaire as a research instrument has been developed in multiple stages following Straub [87] methodology. First, it has been needed to perform an extensive literature review and according to Dialectical systems theory [20] determine all important but subjectively professional enough selected only important indicators and their interdependence. The questionnaire used bases mainly on the MER-model theory [23], taking into consideration the theoretical background (Section 2) introduced information. Following the MER-model theory [23], selected indicators were adopted from Štrukelj [9] (See Appendix A, Table A1). Second, to ensure construct validity and reliability, it has been needed to perform the validation of the adopted questionnaire within researched soft factors—organisational values, organisational culture, organisational ethics, stakeholders’ interests and business policy innovation (BPI) frame. All indicators of the researched soft factors were measured on a 7-point Likert scale varying from “strongly disagree” (rate 1) to “strongly agree” (rate 7). Third, authors included demographic information needed. Fourth, the questionnaire has been trial exploratory tested among 30 organisations’ owners, governors or top managers—key stakeholders who are responsible for business policy innovation. Fifth, in the trial, exploratory test stage authors considered the prepositions on the questionnaire items amendment and their language/interpretation. Based on this, authors incorporated several small changes into the questionnaire. Sixth, authors evaluated the questionnaire reliability; the calculated Cronbach’s alpha values exceed the value 0.5 and thus indicated a level of reliability which is satisfactory [88]. Final scales and researched soft factors indicators are listed in Appendix A, Table A1. Research methodology used is described in Section 4.

4. Methodology

By using the developed questionnaire, the main hypothesis (H1) and all four hypotheses by which the main hypothesis is confirmed (H1a–H1d) were tested empirically. Organisations included into research were selected based on four criteria:

- The headquarters of the organisation had to be in Slovenia;

- Organisations had to operate its business at least for 10 years;

- The research instrument had to be fulfilled by the owner, governor or top manager;

- Owner, governor or top manager had to work at least five years in this organisation.

The sample has been obtained using random stratified sampling method. Survey pool data on organisations were obtained from Bizi.si (www.bizi.si)—Slovenian business directory. The search of organisations according to their field of activity has been performed using the categorization of SSCAF (http://www.stat.si/doc/pub/skd.pdf)—Slovenian Standard Classification of Activities Fields. Randomly selected/randomized stratified sample has been used: the share of every field in listed field of organisations activities has been taking into account (33% organisations from the first, 33% organisations from the second and 33% organisations from the last third of listed organisations). First, electronic mail has been sent to 4200 selected organisations for explaining the purpose of the study and for verifying matching of organisations with selected criteria. The agreement of 788 organisations about the participation in the research has been obtained. The second electronic mail with a hyper-link to the Web-enabled online questionnaire has been sent to them. There were 734 properly completed research instruments, which were later analysed.

SPSS program has been used to perform an Exploratory Factor Analysis (EFA). There were detected four factors of organisational values (Values_1, Values_2, Values_3, and Values_4), three factors of organisational culture (Culture_1, Culture_2, and Culture_3), one factor of organisational ethics (Ethics_1), two factors of stakeholders’ interests (Interest_1, and Interest_2) and one factor of business policy innovation (BPI), thus together eleven factors.

To estimate the parameters in a researched hierarchical model, structural equation modelling (SEM) approach, which is based on covariance, and partial least squares (PLS) approach–SEM, which is based on component, has been employed. PLS approach has important strengths, e.g., [25] it is a predicative technique, therefore also appropriate for researches where theoretical background is less developed; it does not require huge measurement scales; factor indeterminacy problems and inadmissible solutions are avoided; identification problems of recursive models are avoided; no presumptions concerning the data are made; no particular distributions for measured factors are mandatory; it is presumed that the mistakes are not correlated—have no mutual relationship or connection; researching with small samples is feasible; and analyses of complex relationships and models are possible [28,29,89,90]. Since PLS approach has many benefits, it has been used. The empirical data were analysed with a PLS technique, using Smart PLS 3.2.8 [24]. Firstly, psychometric properties with evaluation of reliability, convergent validity and discriminant validity of all measurement scales were examined (Section 5.2). Secondly, structural model and main hypothesis (H1) with hypotheses (H1a, H1b, H1c and H1d) were tested and analysed. Path significance has been estimated using bootstrapping resampling technique with 5000 sub-samples as proposed by Ringle et al. [24] (Section 5.3). Thirdly, predictive accuracy (reliability) of model has been tested through blindfolding procedure, which utilizes a cross-validation (cv) strategy and reports cv-communality and cv-redundancy for factors and indicators (also Section 5.3), and fourthly, importance-performance map analysis (IPMA) has been calculated (Section 5.4), which presents path information in a different way [91]. Standard PLS analysis provides information on the relative importance of constructs; IPMA analysis expend this with performance. It also explains relationships among constructs in the structural model. Ringle et al. [24] pointed out that the IPMA broadens the results of PLS by taking the performance of each factor into account. Authors analysed data following the guidelines set out by Henseler et al. [27] and Garson [91]. Research results and analysis presentation with descriptive statistics, measurement model, structural model, hypotheses testing and the importance-performance map analysis explanation are described in Section 5.

5. Results and Analysis

5.1. Descriptive Statistics

A total of 734 research instrument respondents’ questionnaires were analysed. The size classes of the organisations included into the survey sample were determined based on the quantitative criteria (2 of 3 of them have to be fulfilled for organisation size to be selected): headcount (number of employees), annual turnover and total balance sheet, as determined in the Slovenian Companies Act [92]. Most organisations (54.90%) were small organisations, followed by 32.95% of micro organisations, 10.00% of medium-sized organisations and 2.15% of large organisations. In all size classes of researched organisations there were more male (69.20%) than female (30.80%) respondents. This goes in line with official Slovenia state data (Statistical Office of Republic of Slovenia [93]), because out of 44,256 organisation managers researched at the end of the year 2010, 68.4% of managers were men and only 31.6% of managers were women. 72.75% of the research instrument respondents were organisation’s owners or governors (47.14% sole owners or governors and 25.61% co-owners or co-governors), and 27.25% of them were organisation’s top managers.

5.2. Measurement Model

All of the factors scales were first assessed by pilot experimental testing. Psychometric properties (explaining measurement model) of these factors scales were for each measurement factor scale assessed with evaluation of reliability (Appendix A, Table A1), convergent validity (Appendix A, Table A1) and discriminant validity (Table 1). Standard PLS algorithm for measurement model assessment [26,27,91] has been used. Two measures of reliability were examined: Cronbach’s alpha (α) and composite reliability (CR). Each of 11 researched factors scales had Cronbach’s alpha (α) exceeding 0.70 and composite reliability (CR) exceeding 0.80 (Appendix A, Table A1), thus guaranteeing adequate reliability for factors measurement scales of the research instrument employed (more than 0.70).

Table 1.

Results of discriminant validity (Fornell-Larcker criteria and heterotrait-monotrait (HTMT) ratio).

Fornell and Larcker’s [94] assessment criteria were employed also to assess convergent validity between researched soft factors. According to cited authors all item factor loadings should be significant and should exceed 0.70, as well as the average variance extracted (AVE) for each construct should exceed 0.50. Appendix A, Table A1, lists item factor loadings; all of item factor loadings were significant at p < 0.001 and also higher than proposed level of 0.70. All average variance extracted (AVE) values exceeded 0.50. Measurement scales show strong convergent validity of the research measurement model.

For testing the hypotheses, 11 factors with 61 items were included into research instrument (Appendix A, Table A1; their explanation can be found below the Table A1).

Discriminant validity has been accessed by Fornell-Larcker’s [94] criteria. The calculations have shown that soft factor measurements that are expected to be unrelated really are unrelated, therefore really measure different aspects. For each soft factor scales the square root of average variance extracted (AVE) should be higher than the bivariate correlations between that factor scale and all other factors scales. The inter-construct correlation matrix (Table 1) proves that square roots of AVE of the principal diagonal elements exceed square roots of AVE of the non-diagonal elements in the same column or row (exceed bivariate correlations). All measurement loadings are higher than 0.70 (the lowest AVE is 0.79—Culture_3 and the highest AVE is 0.98—Culture_2), and that represents well-fitting reflective measurement model [27]; cross-loadings are lower (data are available from authors). This evaluation shows that there is no high correlation between researched factors, which should measure (and in our case confirmed measure) theoretically various concepts. Although measures of Fornell-Larcker criterion and examinations of cross-loadings are recognised as valid methods for evaluating the discriminant validity of a PLS model, these two methods have limitations [91]. Henseler et al. [27] pointed out that discriminant validity is better revealed by the HTMT ratio of correlations. HTMT ratio is the geometric mean of the heterotrait-heteromethod correlations divided by the average of the monotrait-heteromethod correlations. In a well-fitting measurement model, heterotrait correlations should have lower values than monotrait correlations, which mean that the HTMT ratio should be below 0.90; in this research measurement model is this requirement fulfilled (the lowest value of HTMT ratio is 0.02—Values_2 and Values_3 and the highest value of HTMT ratio is 0.41—Interests_2) (Table 1). Thus discriminant validity of all eleven factors scales is adequate, although the differences in findings accessed by Fornell-Larcker’s [94] criteria and HTMT ration should be in the future in-depth researched to explore the relevance of the results gained. Still, it is reliable that results, which are confirming hypothesized structural paths between factors, are truthful.

The value of standardized root mean square residual (SRMS) measures the difference among the observed correlation matrix and the model. SRMS of this research model is 0.075., That means the measurement model is justifiable, since it has good fit if SRMS has lower value than 0.10 [91].

5.3. Structural Model and Hypotheses Testing

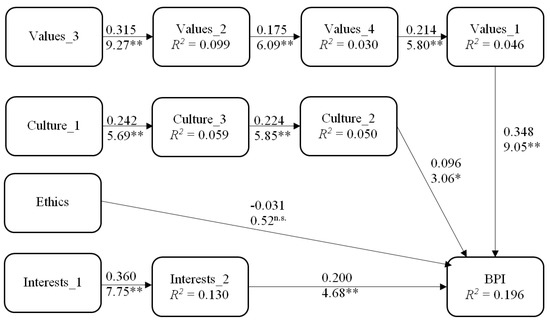

For structural model testing the path significance and magnitude of each of hypotheses H1a–H1d as well as the general explanatory power of the developed structural model has been examined. Based on bootstrapping with 5000 subsamples, the hypotheses H1a, H1b, H1c and H1d testing results were analysed to test the statistical significance of each path coefficient using t-tests (followed Chin’s recommendations [25]) (Table 2). The structural model (Figure 2) indicates predictive power of the variance explained (R2) in key endogenous constructs. Following Cohen’s [95] recommendations, all R2 may be described as ‘weak’. The findings show that this research structural model explains part of variance in the endogenous variables, with an average R2 of 0.09 (see Table 3).

Table 2.

Hypothesized relationships.

Figure 2.

Results of structural model analysis a. a Path significance (t-values): ** p < 0.01; * p < 0.1; n.s.—not statistically significant/confirmed.

Table 3.

Explained variance (R2), blindfolding results of cv-communality (H2) and blindfolding results of cv-redundancy (Q2).

This research confirmed all relationships included into the structural model except effect of business ethics on business policy innovation (BPI) as statistically significant (see Table 2 and Figure 2), thus hypotheses H1a, H1b and H1d and consequently also the main hypothesis H1 are confirmed. The exception is H1c, which is not statistically significant and thus not confirmed. Chain of values through four factors of values, namely Values_3 to Values_2 (β = 0.32, p < 0.01), Values_2 to Values_4 (β = 0.18, p < 0.01), Values_4 to Values_1 (β = 0.21, p < 0.01) and Values_1 has a significant effect on BPI (β = 0.35, p <0.01). Thus H1a is confirmed. Chain of three culture factors, namely Culture_1 to Culture_3 (β = 0.24, p < 0.01), Culture_3 to Culture_2 (β = 0.22, p < 0.01) and Culture_2 has a significant effect on BPI (β = 0.10, p < 0.1). Thus H1b is confirmed. Factor Ethics does not have a statistically significant effect on BPI (β = −0.03, p > 0.01). Thus H1c is not confirmed. Chain of two factors of Interests, namely Interests_1 to Interests_2 (β = 0.36; p < 0.01) and Interests_2 has a significant effect on BPI (β = 0.20; p < 0.01). Thus H1d is confirmed. Therefore, also main hypothesis H1 is confirmed. Consequently, also conceptual research model with hypotheses stated, developed in Section 3 (and showed in Figure 1), which logically flow from the theoretical backgrounds (Section 2), is proved to be valid. Figure 2 shows that statistically confirmed from the theory developed hypothesis H1 and hypotheses H1a, H1b and H1d are valid; only the hypothesis H1c cannot be confirmed as valid, since in the research instrument used it is not significant, thus has not been statistically confirmed (see Table 2 and Figure 2).

In addition to evaluating the size of R2 values as a standard of predictive accuracy, authors also researched Stone-Geisser’s Q2 value as a standard of predictive relevance. The blindfolding technique has been suggested by Wold [96]. Blindfolding utilizes a cross-validation (cv) strategy and reports cv-communality and cv-redundancy as well for factors as for indicators. The cv-redundancy index (Stone-Geisser’s Q2) measures the quality of the structural model, while the cv-communality index (H2) measures the quality of the measurement model. If Q2 is higher than 0, this implies that the PLS-SEM structural model is predictive [91]. Average value of Q2 of this research structural model is 0.06, which indicates that the structural model is predictive. As shown in Table 3, the measurement model (with average value of H2 = 0.51) reveals higher quality than the structural model (with average value of Q2 = 0.06), but both of them meet the criteria for their successful use.

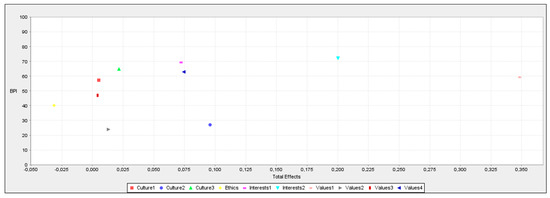

5.4. The Importance-Performance Map Analysis

Usual PLS-SEM analysis assure researcher details about the significance of factors compared to other factors included in the structural research model. The importance-performance map analysis (IPMA) can be good when used for extending the results of PLS-SEM creating supplementary findings and interpretations by combining the analysis of the importance (I) and performance (P) dimensions in practical PLS-SEM applications [24], showing both dimensions in a map (M) analysis (A). IPMA takes also the performance of each factor into account, thus the conclusions are even more relevant. It applies divergent procedures of demonstrating path information and exhibits direct determination of the relative importance of in the PLS model included factors (latent variables) [91]. The importance-performance map analysis (IPMA) permit prioritizing areas demanding improvement. As an outcome, factors (spheres) with relatively high importance and relatively low performance are identified and may be improved with appropriate governance and management activities undertaken. Table 4 and Figure 3 show the importance and performance of the various factors for the endogenous target factor of business policy innovation (BPI). In Figure 3, importance is shown on the abscissa (x-axis) and performance is shown on the ordinate (y-axis).

Table 4.

The importance-performance map for business policy innovation (BPI).

Figure 3.

Results of importance-performance map sowing effects of researched soft factors scales on business policy innovation (BPI).

Table 4 and Figure 3 show that when employing business policy innovation (BPI), e.g., towards business ethics, social responsibility or sustainability for developing more sustainable business policy, management and practice, (1) some viewpoints of organisation’s (key stakeholder’s) values (Values_1) and (2) stakeholders’ (owners or governors and/or (top) managers) interests (Interests_2) are mostly important. Therefore, when planning business policy innovation (BPI), owners or governors (and/or top managers if decided so) should be mostly aware of (1) values of organisation’s key stakeholders about co-workers/employee goals consideration, social goals/social responsibility consideration, behaviour in the organisation (internal orientation) compliance with environmental objectives (e.g., towards social responsibility and preserving all kinds of life forms on planet Earth), short-term goals (mainly in business practice oriented), management (leadership) style, external behaviour (external orientation), innovation directions (also towards business policy innovation), long-term goals (which are part of business policy), sales growth (horizontal, vertical), quality of products/services sold (in line with business strategies), risk relation, profits for new investments (towards long-term development), geographical expansion (horizontal), ownership relationship (consideration of their values), relation to government (and economic policy makers) and as well as about (2) importance of owners or governors and/or managers interests for BPI (See Appendix A, Table A1).

Research results and analysis discussion are introduced in Section 6.

6. Discussion

The identification of influence of requisitely holistic selected soft factors on business policy innovation (BPI) for developing more sustainable business policy, management and practice has been the aim of this research, which has been fulfilled. From the MER-model frame there were four soft factors influencing BPI identified [8,9,22], taking also other cited literature recognitions into consideration. The relationship between these factors and their impact on business policy innovation (BPI) has been observed. Taking research results and analysis into consideration (Section 5), the main hypothesis H1: Soft factors influence business policy innovation (BPI) can be confirmed.

The empirical data were analysed with a PLS technique, using Smart PLS 3.2.8 [24]. Evaluation of psychometric properties showed adequate reliability for factors measurement scales (Appendix A, Table A1): Cronbach’s alpha (α) values are exceeding 0.70 (the lowest α value has factor Culture_3: Importance of culture for BPI: α = 0.703; the highest α value has factor Ethics: The way of achieving organisational credibility: α = 0.970) and composite reliability (CR) values are exceeding 0.80 (the lowest CR value has also factor Culture_3: Importance of culture for BPI: CR = 0.834; the highest CR value has factor Culture_2: Culture of the use of information technology: CR = 0.982).

Measurement scales show strong convergent validity and adequate discriminant validity of measurement model. When assessing convergent validity, we found out that all item factor loadings are significant at p < 0.001 and exceed 0.70, as well as the average variance extracted (AVE) for each construct exceeds 0.50 (Fornell and Larcker’s [94] assessment criteria are fulfilled) (Appendix, Table A1). In addition, discriminant validity has been accessed by Fornell-Larcker’s [94] criteria and HTMT ratio and is adequate. Fornell-Larcker’s [94] criteria are fulfilled and evaluation shows that there is no high correlation between researched factors. All measurement loadings are higher than 0.70 (the lowest AVE value is 0.79—factor Culture_3: Importance of culture for BPI; the highest AVE value is 0.98—factor Culture_2: Culture of the use of information technology); that represents well-fitting reflective measurement model [27]; cross-loadings are lower. The discriminant validity is better revealed by the HTMT ratio of correlations (Henseler et al. [27]), therefore we researched also HTMT ratio values. The HTMT ratio should be below 0.90, which is in our research fulfilled (the lowest value of HTMT ratio is 0.02—factors Values_2 and Values_3; the highest value of HTMT ratio is 0.41—factor Interests_2) (Table 1). The differences in these findings accessed by Fornell-Larcker’s [94] criteria and HTMT ratio should be in the future in-depth researched to explore the relevance of the results gained.

Structural model and main hypothesis (H1) with hypotheses (H1.1–H1.4) were tested and analysed. As suggested by Ringle et al. [24] path significance has been estimated using bootstrapping resampling technique with 5000 sub-samples. PLS analysis showed (Table 2 and Figure 2), that the organisational values have through factor Values_1, which combines sixteen indicators representing the values of organisation’s key stakeholders, positive direct effect on BPI (β = 0.348; p < 0.01). This confirms our hypothesis (H1a): Organisational values have positive and direct effect on business policy innovation (BPI). Values have statistically confirmed the strongest influence on BPI among all factors studied. Research has also shown that there are more value factors, which have through chain of value factors (namely Values_3 → Values_2 → Values_4 → Values_1) impact on BPI. Factor Values_3, which highlights the good and bad aspects of the organisation’s key stakeholders’ values extremes, has positive direct effect on factor Values_2 (β = 0.315; p < 0.01), which highlights the importance of analysis of the values of organisation’s key stakeholders. Factor Values_2 has very weak positive effect on factor Values_4 (β = 0.175; p < 0.01), which stresses out the awareness about the importance of the examination of the values of organisation’s key stakeholders and has positive direct effect on factor Values_1 (β = 0.214; p < 0.01). As mentioned, factor Values_1 represents a selection of the values of organisation’s key stakeholders, and has a positive direct effect on BPI.

Presented research results confirm the importance of organisational values for business policy innovation, which is in accordance to already mentioned studies. Our research thus requisitely holistic and quantitative confirms the fragmented findings of [65,66,67,68,69,70] and therefore contributes to the development of theory in this field.

Research has also shown that chain of factors culture (namely Culture_1 → Culture_3 → Culture_2) has through the factor Culture_2, which represents culture of the use of information technology during making strategic decisions, weak positive direct effect on factor business policy innovation (BPI) (β = 0.096; p < 0.1). This confirms our hypothesis (H1b): Organisational culture has positive and direct effect on business policy innovation (BPI). Factor Culture_1, which represents culture of taking into perception all stakeholders, has positive direct effect on factor Culture_3 (β = 0.242; p < 0.01), which stressed the importance of culture for BPI. Factor Culture_3 has positive direct effect on factor Culture_2 (β = 0.224; p < 0.01). As mentioned, factor Culture_2 represents culture of the use of information technology at the time of strategic decisions making, and has a positive direct effect on BPI.

This indicates that by drawing attention to determined values (and norms), owners, governors or (top) managers can build an organisational culture that leads to preferred organisational behaviour towards business policy innovation requirements. Our research, thus requisitely holistic and quantitative, confirms the fragmented findings of [72,73,74,75,76,77] and therefore contributes to the development of theory in this field.

Factor Ethics, which stressed the importance of achieving organisational credibility and expressed the way how to gain stakeholders to believe and trust the organisation, has not statistically confirmed effect on BPI (β = −0.031; p > 0.1), which does not confirm our hypothesis (H1c): Organisational ethics has positive and direct effect on business policy innovation (BPI). In spite of that, this result only confirms the need towards raising awareness among individuals, organisations and society as a whole about the significance of business ethics, social responsibility and sustainable development [5,13]. Obviously, in practice this area is still not significant enough. With increasing awareness of ethical issues, owners and/or governors and managers must lead their organisations towards enhancing the trust of all stakeholders, thus credibility gained through social responsibility and business ethics, which results in sustainable development and improved performance. Our research thus cannot quantitatively confirm the fragmented findings of [5,13,47,48,49,50,73,79] but nevertheless therefore perhaps even more contributes to the development of theory in this field.

Factor Interests_1, which stresses the importance of interests of external stakeholders for BPI, has positive direct effect on factor Interests_2 (β = 0.360; p < 0.01), which stresses the importance of interests of internal stakeholders for BPI. Factor Interests_2 has positive direct effect on business policy innovation (BPI) (β = 0.200; p < 0.01), which is logical since BPI is directly decided by internal stakeholders; external stakeholders can only influence it indirectly through the enforce of their interests by internal stakeholders. These findings provide empirical support for confirming hypothesis (H1d): Stakeholders’ interests have positive and direct effect on business policy innovation (BPI).

Consequently, the research results suggest that divergent stakeholders’ interests must be taken into consideration when developing more sustainable business policy, thus management and practice, and this process should help increasing the effectiveness of corporate social responsibility or other similar policies for the benefit of both individuals as well as organisations and society. Our research thus requisitely holistic and quantitatively confirms the fragmented findings of [9,15,58,85,97] and therefore contributes to the development of theory in this field.

Among the four factors that have been investigated were no other statistically significant relationships. Selected soft factors organisation’s values, organisation’s culture and stakeholders’ interests have positive statistically proved effect on business policy innovation (BPI), while selected soft factor organisation’s ethics has not statistically confirmed significant influence on business policy innovation (BPI). Three out of four researched selected soft factors have a positive statistically confirmed effect on business policy innovation (BPI), therefore the main hypothesis (H1): Soft factors influence business policy innovation (BPI) can be confirmed.

Even more, our analysis confirms that the developed research model has predictive relevance (all values of Q2 are higher than 0, with average value 0.06; see Section 5.3, Table 3). Namely, predictive accuracy (reliability) of the model has been tested through blindfolding procedure, which utilizes a cross-validation (cv) strategy and reports cv-communality and cv-redundancy for factors and indicators. The aim of the research is to improve the understanding how the impact of selected soft factors can extend the level of business policy innovation (BPI), so that the developed strategic model could be used for developing more sustainable business policy, management and practice. On the bases of importance-performance map analysis (IPMA) results, researched organisations can improve their business policy innovation (BPI) mainly through targeting organisation’s values (Values_1) and organisation’s interests (Interests_2), which have the highest importance among researched constructs on business policy innovation (BPI) (Section 5, Table 4 and Figure 3). These two factors are relatively more important than other factors including into the developed structural model. Thus, we are able to draw the conclusion that because the (1) Values_1 factor is of the highest importance (0.348), owners, governors or (top) managers should place the highest emphasis on these values. Performance is not the highest in terms of this factor (59.183%), so it might make sense to improve it. Factor (2) Interests_2 has the second highest importance (0.2), which can be improved. However, it has the highest performance value (72.128%). Factor (3) Interests_1, which is third in importance (0.072), also has a high performance value (69.221%). This means that owners or governors or (top) managers are aware of the importance of interest alignment (Interests_2 and Interests_1). Factor Interests_1 already belongs to a second set of factors that would make sense to improve. We also rank in the second set of factors according to the importance factors Values_4, Culture_2, Culture_3, Values_2, Culture_1, Values_3 and Ethics. The latter factor (Ethics) even has a negative impact on importance (−0.031), indicating that ethics is not relevant to the organisations studied. This is a very alarming result of this research, which means not only owners, governors or (top) managers but also economic policy makers need to pay attention to, and should take appropriate measures to avoid this ignorance of ethics importance. Among the factors that should be improved, we especially highlight the Culture_2 and Values_2 factors. Though these two factors are not very important (0.096 Culture_2 and 0.013 Values_2), their performance is very low (27.12% Culture_2 and 24.014% Values_2) and thus needs to be improved. The factor Culture_2 refers to culture of not enough using of information technology (IT) when making strategic decisions. The factor Values_2 refers to analysing the values system of organisation’s key stakeholders, which is not used enough and therefore the synergy among key stakeholders cannot be exploited. Knowledge management theory offers several approaches for the development of the organisational commitment [98], which should be taken into consideration when improving these factors performance.

Conclusions with practical applications of the research results and further research development recommendations are described in Section 7.

7. Conclusions with Further Research Development Recommendations

The paper reveals the importance of soft factors influencing business policy innovation based on the principles of MER-model of integral governance and management. Finding the synergy between qualitative theoretical research and quantitative applicative research, it discloses relevance of a theoretically designed strategic model for researching soft factors for developing more sustainable business policy, management and practice. In that framework, the paper on a theoretical level discusses the need for requisitely holistic exploring of, in line with systems theory, subjectively selected soft factors by taking into consideration interdependently innovations in organisational values, organisational culture, organisational business ethics and stakeholders’ interests. In addition, we developed a strategic model for researching soft factors and empirically tested their influence on business policy innovation. The developed theoretical model can be a reminder of the importance of soft factors influencing the development of more sustainable business policy, management and practice. Taking into account the above considerations, it is evident that the influence of selected soft factors on business policy innovation has not been examined enough in the literature. This provides a fruitful basis for discussion on their role in making recommendations for developing more sustainable business policy, thus management and practice. This research fulfils the current literature gap on factors that are influencing business policy innovation (BPI). Applicative research done in the EU provides theoretical and practical insights for both researchers and practitioners as well as for economic policy makers.

The research problem addresses the question whether and how selected soft factors influence the development of more sustainable business policy, management and practice. The applicative research conducted on a sample of 734 organisations confirmed that the selected soft factors organisation values, culture and key stakeholders’ interests, which have been shown in this research as chains, positively influence business policy innovation (BPI). Normally, researchers are exploring more tangible factors influencing BPI, but this research has empirically shown, using advanced structural equation modelling (SEM) based partial least squares (PLS) method, that also intangible factors (we named them soft factors) affect BPI. Business policy innovation (BPI) is the most influenced by organisation’s values (β = 0.348; p < 0.01), then stakeholders’ interests (β = 0.200; p < 0.01), at least among researched soft factors it is affected by organisation’s culture (β = 0.096; p < 0.1).

These research results indicate that among selected soft factors organisational values represent the most important driver of business policy innovation. As the world is changing, organisational values evolve too. Therefore, it is important for owners or governors or managers to respect the values of different key stakeholders and their synergy. Values innovation further results in changes of business policy, other policies, strategies, structures, tactics and procedures in the process of governance and management, information technology process and in business practice. In rapidly changing organisations, this could be seen as the main reason why organisational values have the most statistically significant impact on business policy innovation. Evidently, values changes are needed for BPI. In order to innovate the development and practice of an organisation towards sustainability, it is necessary to influence the development of values of their stakeholders and to ensure that stakeholders’ values support organisation orientation towards sustainability. This is possible to realise only on long-term, since personal values are in-depth grounded in every individual and influence organisational values, including core values among which sustainability should be classified.

Since organisations can be viewed as an integration of stakeholders, their interests can be used as the foundation for business policy evaluation, as well as for change of strategies. Respecting the view that business policy can be improved with corporate social responsibility in our quantitative research instrument incorporated into organisational values and business ethics, our research underpins the theoretical arguments offered in previous researches regarding the presence of a positive correlation among corporate social responsibility and business policy innovation. These outcomes additionally augment the significance of stakeholders’ interests for business policy innovation. To be specific, BPI is directly defined by internal stakeholders, e.g., owners or governors, with the help of top managers. External stakeholders can influence BPI indirectly, through influencing the interests of internal stakeholders, mainly owners or governors. This conclusion is especially engaging in light of the fact that it underpins stakeholder theory according to which formulating responsible and sustainable business policy will enable all relevant stakeholders to achieve long-term strategic goals through different developmental policies and actions. Given the fact that interests derive from values, we propose to influence them through the prism of the already mentioned influence on values innovation. Values are derived solely from internal/intrinsic motivation, but interests can also be driven by external/extrinsic motivation. Therefore, interests are easier to influence than values. This can be an important starting point not only for owners, governors or managers of organisations, but also for economic policy makers. Extrinsic/external motivation can namely be achieved through many methods of human resource management.

We also showed that organisational culture has statistically significant influence on business policy innovation. Depending on the values and norms applied in the organisational culture, top management decides business policy realisation form, i.e., selects the strategies and designs according to strategies appropriate organisational structure, managers model the management style, and employees define their grounds and needs. It implies that organisational culture through presumptions, beliefs and values shared by the managers and employees determine the way in which business policy should be changed. Based on these recognitions, it is possible to make a recommendation that it is necessary that organisations introduce a culture of respect of all stakeholders, which can be easier achieved through the introduction of computerized information databases with information about different stakeholders. Namely, information technology can serve as a convenient tool for successfully managing relationships with all stakeholders.

In the study, we have not proved that business policy innovation (BPI) is statistically significantly influenced by organisation’s ethics (β = −0.031; p > 0.1). The factor Ethics constitutes of different items representing need of taking responsibility from every aspect, also when not being direct responsible; truthful, open and both-sided communication with all stakeholders; and conscious commitment to innovation both products/services as well as processes and in human relationships (social innovations). This factor therefore highlights the need for technological and non-technological innovations. The latter, non-technological innovations, includes a focus on sustainable development, which is clearly not yet understood by the organisations involved in the research. Reasons why has not been statistically confirmed that business ethics influence BPI need to be investigated in future research. This does not mean that the organisation’s business ethics are not important, as all researched soft factors are interconnected. It only means that in the future to ethics of people, organisations and societies (including their social responsibility and sustainable development) need to be paid even more attention. To raise awareness from this aspect is thus very important.

We extended standard PLS-SEM analysis results with importance-performance map analysis (IPMA). PLS-SEM research gives us information about the importance of each factor. IPMA extends these recognitions in a way that additionally takes the factors’ performance into explanation. Therefore, importance and performance can be taken into consideration when drawing conclusion. That is especially significant when emphasizing importance of owners or governors or managerial decision-making. We suggest that decision-makers first and fore most emphasise improvement of the performance of high important factors concerning their explanation of the construct examined and which has comparatively low performance. Arising from our research recognitions, decision-makers should give most emphasis on factor Values_1 (the influence of values of organisation’s key stakeholders), which has the highest importance (0.348) but does not have the highest performance (59.183%), so it would be reasonable to improve the performance of this factor. Another factor that is also worth focusing on is the Interests_2 factor (owners and managers’ interests). Among all the factors studied, it has the highest performance value (72.128%). The Interests_1 factor also has high performance (69.221%), which proves that in the 734 organisations studied are aware about the performance regarding interests. These two factors stand out from the other factors in terms of impotence. Other two factors stand out from the other factors in terms of performance. These are factors Culture_2 (culture of IT use during strategic decision-making) and Values_2 (the value systems of organisation’s key stakeholder). The factor that has the third worst performance and even negative importance is the Ethics factor (achieving ethics through credibility). Decision-makers should therefore focus particular attention also towards improving the performance of these three factors.

Other practical applications of the research results can be based mainly on requirement towards creating a sufficiently high level of consciousness of the significance of (selected) soft factors affecting business policy innovation (BPI). This could be achieved through appropriate policy makers’ recommendations to the organisations, published on the Internet, in special publications and also sent directly to owners or governors or managers of organisations.

Our research results could be employed as a meaningful starting point for owners or governors or managers, for developing future steps in formulating business policy and other policies aligned with increasing importance of sustainability, business ethics and corporate social responsibility. Thus, decisions could take into consideration recognitions regarding the necessity to take into examination significance of selected soft factors—organisational values, culture, business ethics and stakeholders’ interests when deciding about business policy innovation towards developing more sustainable business policy, thus management and practice. Accordingly, owners, governors or managers can create their decisions about future business policies based on current significance of selected soft factors. An extensive insight into the role of these factors may offer them a fine framework to begin their efforts towards achieving higher level of corporate social responsibility and business ethics, which leads to sustainable development. We can conclude that this comprehensive research about influence of selected soft factors on business policy innovation contributes to overcome identified research gap. In addition, this research can be helpful for making better managerial decisions and recommendations for developing more sustainable business policy, thus management and practice.

In addition, economic policy makers should reflect on the findings of this research. It would probably make sense to send organisations a reminder each year to direct them towards more ethical behaviour, more social responsibility and sustainability. This reminder could every year target another aspect of the sustainability orientation focus. At the same time, it would make sense to start developing appropriate legislation that would oblige also micro, small and medium-sized (not only large) organisations to impose an obligation on some form of non-financial reporting. This would raise the awareness of the importance of sustainable organisation development for existing and future generations.