European National Road Authorities and Circular Economy: An Insight into Their Approaches

Abstract

1. Introduction

- How do NRAs realize their transition to more circular approaches?

- How do NRAs implement and communicate their approaches on CE?

2. Literature Review

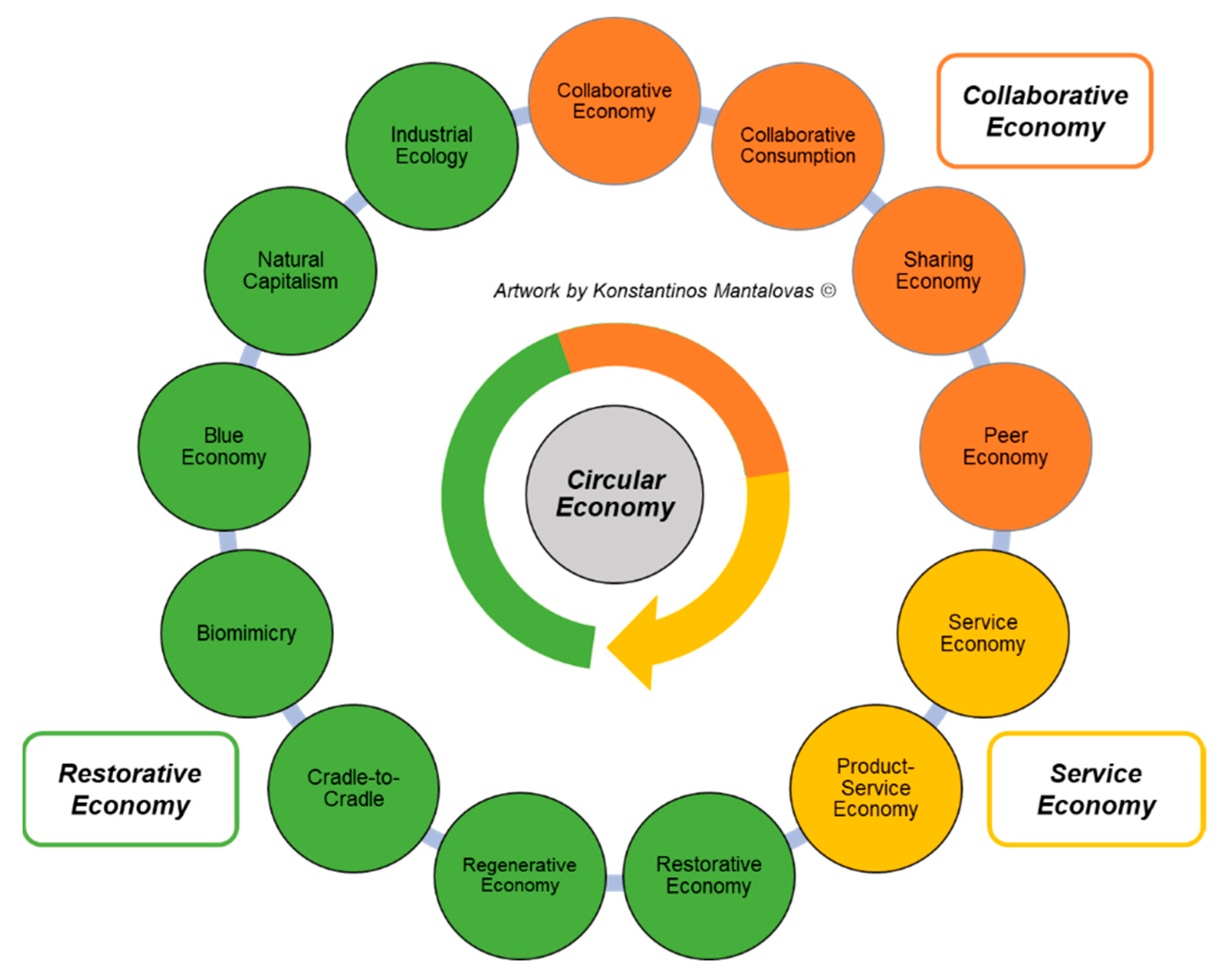

2.1. Circular Economy

2.2. Circular Economy, Asphalt Production and Use

2.3. Implementation of Circular Economy Principles in Road Construction and Maintenance

- Resource efficient construction.

- Recycled content: high percentages of materials are recycled into asphalt pavements, while complying with the performance requirements for the road pavement.

- Excavated materials, soil, and wastes management: excavated materials, soils and wastes that are not hazardous can be reused on site.

- Water and habitat conservation: road drainage systems must adequately drain both stormwater from the road surface and sub-surface water from groundwater flows. Moreover, it is suggested that Sustainable Drainage Systems (SUDS) are promoted in an attempt to re-use the drained water.

- Maintenance and rehabilitation strategies: a Maintenance & Rehabilitation Plan, that considers all the aforementioned suggestions, should be developed during detailed design.

- Better knowledge is needed about construction techniques to facilitate deconstruction and to enhance durability and adaptability of built assets.

- Durability depends on better design, improved performance of construction products and information sharing.

- Prevent premature asset demolition by developing a new design culture.

- Design products and systems so that they can be easily reused, repaired, recycled, or recovered.

3. Methods

3.1. Questionnaire to National Road Authorities

- Austria (ASFiNAG)

- Denmark (Danish Road Directorate—Vejdirektoratet)

- Germany (Federal Ministry of Transport, Building and Urban Development—Bundesministerium für Verkehr und digitale Infrastruktur)

- United Kingdom (Highways England, Transport Scotland, Welsh Government, Roads Service)

- Lithuania (Lithuanian Road Administration and family of road engineers)

- Norway (Norwegian Public Roads Administration—NPRA)

- Slovenia (Slovenian Roads & Infrastructure Agency)

- Sweden (Swedish Transport Administration Trafikverket)

- Netherlands (Rijkswaterstaat, State advisors for urban development & infrastructure)

3.2. Web Search: NRAs and CE Communication

4. Results and Analysis

4.1. Analysis of Roadmaps Produced by National/Regional Authorities towards Circular Economy

4.2. Analysis of the Questionnaire to NRAs

- Design out/minimize waste

- Use waste as a resource

- Preserve and extend what is already made (usually translated as “preventive maintenance”)

- Preserve and extend what is already made

- Design out/minimize waste

- Removing restrictions on asphalt recycling to minimize waste

- Extending the service life of asphalt pavements, usually by preventive maintenance

- Testing waste materials for potential utilization as resources in asphalt pavements

4.3. Analysis of the Web Search: NRAs and CE Communication

5. Discussion and Conclusions

- The rethinking of their designs, minimizing the use of materials and improving the durability of the asphalt pavements while allowing their reuse, repair, recycle or recovery.

- The research and development of alternative, more environmentally friendly, construction and maintenance methods.

- The utilization of soil and waste during the construction and maintenance phases as useful materials.

- Development of end of life strategies, focusing on the possibility of closed loop approaches and/or upcycling.

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

Disclaimer

Appendix A

- Are you familiar with the concept of Circular Economy and its principles?

- If yes, which principles of Circular Economy are you familiar with? (tick as many as needed)

- Design out/minimize waste

- Use waste as resource (recycle, reuse)

- Prioritize regenerative resources

- Preserve and extend what is already made

- Other, please specify:

- Which of those principles have already been introduced within established pavement life cycle management practices?

- Design out/minimize waste

- Use waste as resource (recycle, reuse)

- Prioritize regenerative resources

- Preserve and extend what is already made

- Other, please specify:

- Which practices are you using to implement those principles for Circular Economy?

- If these principles are currently not implemented into practices, which reasons/challenges are impeding it? Is there a future strategy to implement them?

- Are there any current metrics/indicators to assess the level of circularity of these practices and/or the pavement management process?

- If yes, which are these metrics/indicators?

- Product Material Circularity Index (MCIP) [Ellen MacArthur foundation (EMF)]

- Company Material Circularity Index (MCIC) [Ellen MacArthur foundation (EMF)]

- End of Life recycling input rate [Available in the EU’s Raw Material Scoreboard and in EC Monitoring framework for the CE (under development)]

- Resource Efficiency [EU Resource Efficiency scoreboard (EURES)]

- Other, please specify:

- If no, which reasons/challenges are impeding their development? Is there a future strategy to define them?

- Has a “Roadmap” towards Circular Economy been produced/published, to achieve more sustainable and circular management of asphalt pavements?

- If yes, could you please provide us with a copy or link to find it

- If not, which are the current challenges, posing as obstacles towards the production of such a roadmap? Is there a future strategy to produce one?

References

- Bringezu, S.; Schütz, H.; Steger, S.; Baudisch, J. International comparison of resource use and its relation to economic growth: The development of total material requirement, direct material inputs and hidden flows and the structure of TMR. Ecol. Econ. 2004, 51, 97–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richard, C.; Amit, P. Exploiting Natural Resources: Growth, Instability, and Conflict in the Middle East and Asia; The Henry L. Stimson Center: Washington DC, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Barbier, E.B. The Concept of Sustainable Economic Development. Environ. Conserv. 1987, 14, 101–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Purvis, B.; Mao, Y.; Robinson, D. Three pillars of sustainability: In search of conceptual origins. Sustain. Sci. 2018, 14, 681–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Comission. European Commission: Roadmap to a Resource Efficient Europe; European Comission: Brussels, Belgium, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Ecorys. Resource Efficiency in the Building Sector: Final Report; European Comission: Brussels, Belgium, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Ellen MacArthur Foundation. Towards a Circular Economy: Business Rationale for an Accelerated Transition; Ellen MacArthur Foundation: Cowes, UK, 2015; pp. 4–20. Available online: https://www.ellenmacarthurfoundation.org/assets/downloads/TCE_Ellen-MacArthur-Foundation-9-Dec-2015.pdf (accessed on 10 June 2020).

- Mantalovas, K.; Di Mino, G. The sustainability of reclaimed asphalt as a resource for road pavement management through a circular economic model. Sustainability 2019, 11, 2234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mantalovas, K.; Di Mino, G. Integrating circularity in the sustainability assessment of asphalt mixtures. Sustainability 2020, 12, 9–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, S.; Hu, S.; Chen, D.; Zhu, B. A case study of a phosphorus chemical firm’s application of resource efficiency and eco-efficiency in industrial metabolism under circular economy. J. Clean. Prod. 2015, 87, 839–849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, Y. An exploration of firms’ awareness and behavior of developing circular economy: An empirical research in China. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2014, 87, 145–152. [Google Scholar]

- Mathews, J.A.; Tan, H. Progress toward a circular economy in China: The drivers (and inhibitors) of eco-industrial initiative. J. Ind. Ecol. 2011, 15, 435–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhijun, F.; Nailing, Y. Putting a circular economy into practice in China. Sustain. Sci. 2007, 2, 95–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frodermann, L. Exploratory Study on Circular Economy Approaches; Springer Science and Business Media LLC.: Berlin, Germany, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Meadows, D.H.M. The Limits to Growth. Club Rome 1972, 102, 27. [Google Scholar]

- Lomborg, B. Environmental Alarmism, Then and Now; Foreign affairs (Council on Foreign Relations): Washington DC, USA, 2012; pp. 1–8. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/297823867_Environmental_Alarmism_Then_and_Now_The_Club_of_Rome’s_Problem-and_Ours (accessed on 10 June 2020).

- Bicket, M.; Guilcher, S.; Hestin, M.; Hudson, C.; Razzini, P.; Tan, A.; ten Brink, P.; van Dijl, E.; Vanner, R.; Watkins, E. Scoping Study to Identify Potential Circular Economy Actions, Priority Sectors, Material Flows and Value Chains; Publications office of the European Union: Luxemburg, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Gregson, N.; Crang, M.; Fuller, S.; Holmes, H. Interrogating the circular economy: The moral economy of resource recovery in the EU. Econ. Soc. 2015, 44, 218–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boulding, K.E. The Economics of the Coming Spaceship Earth in Environmental Quality Issues in a Growing Economy; Daly, H.E., Ed.; Johns Hopkins University Press: Baltimore, MD, USA, 1966; pp. 4–14. [Google Scholar]

- DOBBS, C.G. Silent Spring. In Forestry: An International Journal of Forest Research; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1963; Volume 36, pp. 195–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellen MacArthur Foundation. Towards the Circular Economy—Economic and Business Rationale for an Accelerated Transition; Ellen MacArthur Foundation: Cowes, UK, 2013; Volume 1, pp. 1–96. Available online: https://www.ellenmacarthurfoundation.org/assets/downloads/publications/EllenMacArthur-Foundation-Towards-the-Circular-Economy-vol.1.pdf (accessed on 10 June 2020).

- Ellen MacArthur Foundation. Cities in the Circular Economy: An Initial Exploration; Ellen MacArthur Foundation: Cowes, UK, 2017; pp. 4–14. Available online: https://www.ellenmacarthurfoundation.org/assets/downloads/publications/Cities-in-the-CE_An-Initial-Exploration.pdf (accessed on 10 June 2020).

- Ellen MacArthur Foundation; GRANTA, LIFE. Circularity Indicators—An Approach to Measuring Circularity: Methodology; Ellen MacArthur Foundation: Cowes, UK, 2015; pp. 7–12. [Google Scholar]

- Ellen MacArthur Foundation. Towards Circular Economy: Opportunities for the Consumer Goods Sector; Ellen MacArthur Foundation: Cowes, UK, 2013; Volume 2, pp. 6–80. Available online: https://www.ellenmacarthurfoundation.org/assets/downloads/publications/TCE_Report2013.pdf (accessed on 10 June 2020).

- Tran, T.; Park, J.Y. Development of a novel co-creative framework for redesigning product service systems. Sustainability 2016, 8, 434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goedkoop, P.J.M.; van Halen, M.J.; te Riele, C.J.G.; Rommens, H.R.M. Product Service systems, Ecological and Economic Basics. Rep. Dutch Ministries Environ. Econ. Aff. 1999, 36, 1–122. [Google Scholar]

- Clark, G.; Kosoris, J.; Hong, L.N.; Crul, M. Design for sustainability: Current trends in sustainable product design and development. Sustainability 2009, 1, 409–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The British Standards Institution (BSI). Framework for Implementing the Principles of the Circular Economy in Organizations—Guide; BSI: London, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Pearce, D.W.; Turner, R.K. Economics of Natural Resources and the Environment; Harvester Wheatsheaf: London, UK, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Ellen MacArthur Foundation. Towards the Circular Economy Volume 3: Accelerating the Scale-Up Across Global Supply Chains; Ellen MacArthur Foundation: Cowes, UK, 2014; pp. 1–64. Available online: https://www.ellenmacarthurfoundation.org/assets/downloads/publications/Towards-the-circular-economy-volume-3.pdf (accessed on 10 June 2020).

- Chen, C. Guidance on the conceptual design of sustainable product—Service systems. Sustainability 2018, 10, 2452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stahel, W.R. The service economy: Wealth without resource consumption? Philos. Trans. R. Soc. A Math. Phys. Eng. Sci. 1997, 355, 1309–1319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Botsman, R.; Rogers, R. What’s Mine Is Yours: The Rise of Collaborative Consumption; Botsman, R., Rogers, R., Eds.; HarperCollinsPublishers: New York, NY, USA, 2010; p. 304. [Google Scholar]

- Hawken, P. The Ecology of Commerce: A Declaration of Sustainability; HarperCollinsPublishers: New York, NY, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- McDonough, W.; Braungart, M. Cradle to Cradle: Remaking The Way We Make Things; North Point Press: New York, NY, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Llorach-Massana, P.; Farreny, R.; Oliver-Sola, J. Are cradle to cradle certified products environmentally preferable? analysis from an LCA approach. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 113, 715–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montana, H.C.A. Bio-ID4S: Biomimicry in Industrial Design for Sustainability: An Integrated Teaching-and-Learning Method; VDM Verlag Dr. Müller: Saarbrücken, Germany, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- De Pauw, I.C.; Karana, E.; Kandachar, P.; Poppelaars, F. Comparing biomimicry and cradle to cradle with ecodesign: A case study of student design projects. J. Clean. Prod. 2014, 78, 174–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reap, J.; Baumeister, D.; Bras, B. Holism, biomimicry and sustainable engineering. IMECE 2008, 42185, 423–431. [Google Scholar]

- Kuo, N.W.; Hsiao, T.Y. An exploratory research of the application of natural capitalism to sustainable tourism management in Taiwan. J. Clean. Prod. 2008, 16, 116–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lovins, L.H.L.; Amory, B.; Paul, H. A road map for natural capitalism. Harv. Bus. Rev. 1999, 77, 145–158. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Erkman, S. Industrial ecology: An historical view. J. Clean. Prod. 1997, 5, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kagawa, S.; Hashimoto, S.; Managi, S. Special issue: Studies on industrial ecology. Environ. Econ. Policy Stud. 2015, 17, 361–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mantalovas, K. Interpreting life cycle assessment results of bio-asphalt pavements for more informed decision-making. In Pavement, Roadway, and Bridge Life Cycle Assessment 2020, Proceedings of the International Symposium on Pavement. Roadway, and Bridge Life Cycle Assessment 2020 (LCA 2020), Sacramento, CA, USA, 3–6 June 2020; Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/342642405_Interpreting_life_cycle_assessment_results_of_bio-recycled_asphalt_pavements_for_more_informed_decision-making (accessed on 30 July 2020).

- Giani, M.I.; Dotelli, G.; Brandini, N.; Zampori, L. Resources, conservation and recycling comparative life cycle assessment of asphalt pavements using reclaimed asphalt, warm mix technology and cold in-place recycling. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2015, 104, 224–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lo Presti, D. Allback2pave: Towards a sustainable recycling of asphalt in wearing courses. In Proceedings of the AIIT International Congress on Transport Infrastructure and Systems, Rome, Italy, 10–12 April 2017; pp. 109–117. [Google Scholar]

- Chiu, C.-T.; Hsu, T.-H.; Yang, W.-F. Life cycle assessment on using recycled materials for rehabilitating asphalt pavements. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2008, 52, 545–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newcomb, D.E.; Ray, B.E.; Epps, J.A. Designing HMA Mixtures with High Rap Content: A Practical Guide; National Asphalt Pavement Association: Lanham, MD, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Song, W.; Huang, B.; Shu, X. Influence of warm-mix asphalt technology and rejuvenator on performance of asphalt mixtures containing 50% reclaimed asphalt pavement. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 192, 191–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Winkle, C.I. Laboratory and Field Evaluation of Hot Mix Asphalt with High Contents of Reclaimed Asphalt Pavement. Master’s Thesis, University of Iowa, Iowa City, IA, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, D.X.; Saleh, M. Evaluation of Mechanical Properties of a New Warm-Mix Asphalt using Sylvaroad Additive. Athens J. Τechnol. Eng. 2017, 4, 83–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berg, A. Reports of the Finnish Environment Institute–Circular Economy for Sustainable Development; Finnish Environment Institute (SYKE): Helsinki, Finland, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Pérez-Acebo, H.; Linares-Unamunzaga, A.; Abejon, R.; Rojí, E. Research Trends in Pavement Management during the First Years of the 21st Century: A Bibliometric Analysis during the 2000–2013 Period. Appl. Sci. 2018, 8, 1041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiao, Y.; Dave, E.V.; Parry, A.; Valle, O.; Mi, L.; Ni, G.; Yuan, Z.; Zhu, Y. Life Cycle Costs Analysis of Reclaimed Asphalt Pavement (RAP) Under Future Climate. Sustainability 2019, 11, 5414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asphalt Pavement Alliance. Recycling & Energy Reduction; Asphalt Pavement Alliance: Lanham, MD, USA, 2017; p. 2. [Google Scholar]

- Williams, B.A.; Willis, J.R.; Ross, T.C. Asphalt Pavement Industry Survey on Recycled Materials and Warm-Mix Asphalt Usage: 2018, Information Series 138, 9th ed.; National Asphalt Pavement Association (NAPA): Greenbelt, MD, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Noferini, L.; Simone, A.; Sangiorgi, C.; Mazzotta, F. Investigation on performances of asphalt mixtures made with Reclaimed Asphalt Pavement: Effects of interaction between virgin and RAP bitumen. Int. J. Pavement Res. Technol. 2017, 10, 322–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blasl, A.; Kraft, J.; Lo Presti, D.; Di Mino, G.; Wellner, F. Performance of asphalt mixes with high recycling rates for wearing layers. In Proceedings of the 6th Eurasphalt Eurobitume Congregation, Prague, Czech Republic, 30 June 2016. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission (EC). European Resource Efficiency Platform (EREP)–Manifesto & Policy Recommendations; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2012; pp. 1–16. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/environment/resource_efficiency/documents/erep_manifesto_and_policy_recommendations_31-03-2014.pdf (accessed on 10 June 2020).

- Ghosh, S.K. Circular Economy: Global Perspective; Springer: Singapore, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- PlatformCB23. Kernmethode Voor Het Meten Van Circulariteit in de Bouw; Platform CB’23: Delft, The Netherlands, 2019; Available online: https://platformcb23.nl/images/downloads/Platform_CB23__Core_method_for_measuring_circularity_in_the_construction_sector_Version_1.0_July_2019.pdf (accessed on 10 June 2020).

- European Commission (EC). Report from the Commission to the European Parliament, the Council, the European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions on the Implementation of the Circular Economy Action Plan; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Garbarino, E.; Quintero, R.R.; Donatello, S.; Caldas, M.G.; Wolf, O. Revision of Green Public Procurement Criteria for Road Design, Construction and Maintenance. Technical Report and Criteria Proposal; European Commision: Brussels, Belgium, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission. Circular Economy Principles for Buildings Design; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Chamber of Commerce and Industry of Slovenia. Ministry of the Environment And Spatial Planning, Republic of Slovenia, the Danube Goes Circular Transnational Strategy to Accelerate Transition Towards a Circular Economy in the Danube Region; Chamber of Commerce and Industry of Slovenia: Ljubljana, Slovenia, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Circular Flanders (Vlaanderen Circulair). Circular Flanders Together towards a Circular Economy—Kick-off Statement; Circular Flanders: Mechelen, Belgium, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Be Circular, Gewestelijk Programma Voor Circulaire Economie; Government of the Brussels-Capital Region: Brussels, Belgium, 2016.

- Pantsar, M. Leading the Cycle—Finnish Road Map to a Circular Economy 2016–2025; SITRA: Helsinki, Finland, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Ministry for Ecological and Solidary Transition. Transition, Ministry for an Ecological and Solidary, 50 Measures for a 100% Circular Economy; Ministry for Ecological and Solidary Transition: Paris, France, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- BMUB. German Resource Efficiency Programme II Programme for the Sustainable Use and Conservation of Natural Resources; Dispatch of Publications by the Federal Government: Rostock, Germany, 2016.

- Hellenic Republic Ministry of Environment & Energy. National Circular Economy Strategy; Ministry of Environment and Energy: Athens, Greece, 2018.

- Ministero dell’Ambiente e della Tutela del Territorio e del Mare and Ministero dello Sviluppo Economico, Towards a Model of Circular Economy for Italy; Ministry of the Environment and Protection of the Territory and the Sea and Ministry of Economic Development: Rome, Italy, 2017.

- Ministère de l’Economie. Ministère du Développement durable et des Infrastructures, and Luxinnovation, Luxembourg as a Knowledge Capital and Testing Ground for a Circular Economy; Ministère de l’Economie: Paris, France, 2015.

- Republica Portuguesa. Leading the Transition—Action plan For Circular Economy in Portugal: 2017–2020; Ministry of Environment: Lisbon, Portugal, 2017. Available online: https://circulareconomy.europa.eu/platform/sites/default/files/strategy_-_portuguese_action_plan_paec_en_version_3.pdf (accessed on 10 June 2020).

- Šalamon, T.; Kos, I.; Novak, B.; Šprinzer, M.; Žurman, T. Strategy for the Transition to Circular Economy in Municipality of Maribor; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2018; Volume 7, pp. 1–32. [Google Scholar]

- Republika Slovenija Vlada Republike Slovenije. Roadmap Towards the Circular Economy in Slovenia; Republika Slovenija Vlada Republike Slovenije: Ljubljana, Slovenia, 2018.

- Junta de Extremadura. Extremadura 2030 Estrategia de Economía Verde y Circular; Junta de Extremadura: Mérida, Spain, 2018; p. 353.

- Catalunya, G.D.E. Impuls a l’economia verda i a l’economia Circular: Competitivitat, eficiènci i innovació D. Of. la General; Government of Catalonia: Barcelona, Spain, 2015.

- Wijsmuller, J. Circulair Den Haag-Transitie naar een Duurzame Economie; City of the Hague: Hague, The Netherlands, 2018; Available online: https://denhaag.raadsinformatie.nl/document/6291317/1/RIS299353_Bijlage_1 (accessed on 10 June 2020).

- Government of Netherlands. A Circular Economy in the Netherlands by 2050; Government of Netherlands: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2016; pp. 1–72.

- Scottish Government. Making Things Last: A Circular Economy Strategy for Scotland; Scottish Government: Edinburgh, Scotland, 2016.

- LWARB. London’s Circular Economy Route Map; LWARB: London, UK, 2017.

- AECOM and Atkins. Circular Economy Approach and Routemap; AECOM: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Chamberlin, L.; Boks, C. Marketing approaches for a circular economy: Using design frameworks to interpret online communications. Sustainability 2018, 10, 2070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Austria, Bulgaria, Croatia, Czech Republic, Germany, Hungary, Romania, Slovak Republic, Slovenia, Ukraine, Moldova, Serbia, Montenegro, Bosnia and Herzegovina |

| Belgium |

| Belgium |

| Finland |

| France |

| Germany |

| Greece |

| Italy |

| Luxemburg |

| Portugal |

| Slovenia |

| Slovenia |

| Spain |

| Spain |

| The Netherlands |

| The Netherlands |

| The Netherlands |

| United Kingdom |

| United Kingdom |

| United Kingdom |

| Highways England (UK) |

|

| Platform CB23 (The Netherlands) |

|

| German Resource Efficiency Programme II |

|

| 50 Measures for a 100% Circular Economy (France) |

|

| Luxembourg as a knowledge capital and testing ground for the Circular Economy |

|

| National Road Authority per Country | CE Implementation Plan and Communication |

|---|---|

| Austria (ASFiNAG) | Sustainability strategies and reports/no specific mention of CE |

| Belgium (Agency for roads and traffic/Wallonia General Direction for roads and traffic) | Sustainability related research and reporting/no specific mention of CE |

| Denmark (Danish Road Directorate—Vejdirektoratet) | Environmental Assessment reports, Sustainability related research and reporting/no specific mention of CE |

| Germany (Federal Ministry of Transport, Building and Urban Development—Bundesministerium für Verkehr und digitale Infrastruktur) | Climate Action Program 2030/CE related: preservation of resources, maximization of resource efficiency, resource cycle management/bio economy |

| United Kingdom (Highways England, Transport Scotland, Welsh Government, Roads Service) | Circular Economy Approach and Route map |

| Lithuania (Lithuanian Road Administration and family of road engineers) | No specific mention of CE |

| Norway (Norwegian Public Roads Administration—NPRA) | Sustainability related research and reporting/no specific mention of CE |

| Slovenia (Slovenian Roads & Infrastructure Agency) | Conferences organized, European Research Council and European Union’s Joint Research Center collaborations for circular economy implementation/Slovenian development days to promote CE |

| Sweden (Swedish Transport Administration—Trafikverket) | Sustainability related research and reporting/nothing related to CE |

| Netherlands (Rijkswaterstaat, State advisors for urban development & infrastructure) | Circular Public Procurement/Resource Efficient business models/National Waste Management Plan |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Mantalovas, K.; Di Mino, G.; Jimenez Del Barco Carrion, A.; Keijzer, E.; Kalman, B.; Parry, T.; Lo Presti, D. European National Road Authorities and Circular Economy: An Insight into Their Approaches. Sustainability 2020, 12, 7160. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12177160

Mantalovas K, Di Mino G, Jimenez Del Barco Carrion A, Keijzer E, Kalman B, Parry T, Lo Presti D. European National Road Authorities and Circular Economy: An Insight into Their Approaches. Sustainability. 2020; 12(17):7160. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12177160

Chicago/Turabian StyleMantalovas, Konstantinos, Gaetano Di Mino, Ana Jimenez Del Barco Carrion, Elisabeth Keijzer, Björn Kalman, Tony Parry, and Davide Lo Presti. 2020. "European National Road Authorities and Circular Economy: An Insight into Their Approaches" Sustainability 12, no. 17: 7160. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12177160

APA StyleMantalovas, K., Di Mino, G., Jimenez Del Barco Carrion, A., Keijzer, E., Kalman, B., Parry, T., & Lo Presti, D. (2020). European National Road Authorities and Circular Economy: An Insight into Their Approaches. Sustainability, 12(17), 7160. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12177160