1. Introduction

Community-Based Tourism Enterprises (CBTEs) are an important reference point within Ecuador’s tourism industry. However, it is not clear how these enterprises manage their administrative and financial processes, or whether they have even implemented some of these processes. There is no evidence of previous studies about this topic, but this does not mean that it is not important to know how these enterprises carry out financial and administrative controls. Furthermore, it could be one of the main determining factors as to whether the enterprises remain in the market.

The objective of this paper is to present the results of the diagnosis of the administrative and financial processes in CBTEs in the Ecuadorian provinces of Pichincha, Imbabura, and Napo. This research is exploratory in nature and consists of a compilation of 28 cases (CBTEs), which are subject to a detailed diagnosis of their administrative and financial processes.

The concept of tourism has changed over time from being massive and careless; damaging architectural, natural, and cultural resources, and leaving aside the interest of the communities [

1]. It has evolved to become an activity that seeks the sustainability of the host community, based on the preservation of resources and maintaining a good quality of life for present and future generations. This concept appeared in the 1980s when the World Commission on Environment and Development defined it as “sustainable development that meets the needs of the present generation without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs” [

2,

3], focusing on the balanced use of resources in order to reach long-term economic, social, and environmental development of nations, with a responsible and collective commitment. As also stated by the World Tourism Organization (WTO), sustainable tourism is defined as “tourism that takes full account of its current and future economic, social and environmental impacts, addressing the needs of visitors, industry, the environment and host communities” [

4].

As a result of a constitutional mandate adopted inside the National Development Plan 2017–2021 [

5], Ecuador is a part of this sustainable development process, with nine objectives framed in three fundamental axes: Lifetime rights for everyone, economy at the service of society, and more society better State. The purpose of this strategic plan is to improve the living conditions of citizens in a permanent and sustainable manner, towards “Sumak Kawsay” [

6] the well-being of Ecuadorians. Article 14 of the Ecuadorian Constitution states: “The right of the population to live in a healthy and ecologically balanced environment that guarantees sustainability and good living (Sumak kawsay) is recognized”. In addition to environmental conservation, the protection of ecosystems, biodiversity and the integrity of the country’s genetic heritage, the prevention of environmental damage, and the recovery of degraded natural areas are declared to be of public interest [

7].

In recent years, tourism has experienced significant growth, especially in 2017 with a 7% increase in tourist arrivals. By 2019, tourist arrivals increased only 4%, which is equivalent to 1461 million visitors worldwide, 15% of which are in the Americas [

8]. In Ecuador, as well, tourism has become an important economic activity that generates significant foreign exchange for the country. In 2018, it contributed US

$ 2392.1 million to the national economy, representing 2 percent of GDP [

9]. According to the World Travel and Tourism Council (WTTC), this represents a total contribution (direct, indirect, and induced) of 5.5% to Ecuador’s total GDP [

10], which places it in third place as a source of non-oil revenue [

11].

In this sustainable context, community tourism is clearly an important part, because it aims for local development by community’s inclusion [

12]. The Caribbean States Association defines it as an alternative for rural communities to generate other incomes towards economies by using cultural, natural, and local resources [

13]; by poverty reduction, new job creation, and the equal distribution of resources generated by this activity to all community members. Ecuador is a pioneer country in this type of tourism, even more since it is a mega-diverse country in cultural, natural, and social aspects [

14]. It was the first country in the world to have a national union, such as the Plurinational Federation of Community Tourism of Ecuador (known as the FEPTCE), which defines community tourism as a relationship between the community and visitors in an intercultural perspective: In organized trip development, consensual participation of its members, guaranteeing adequate natural resources management, heritage appreciation, nationalities cultural and territorial rights, and equitable distribution of the generated benefits [

15].

In a review of the literature, we found an increasing number of papers on Community-Based Tourism (CBT). To get an approximate idea of the interest of this subject among researchers, Mtapuri et al. (2015) [

16] reported 400 articles on CBT covered in 136 different journals since its emergence in the 1980s. Many of these researches analyze real cases of Community-Based Tourism Enterprises (CBTEs) located mainly in Africa (e.g., in Kenya [

17,

18,

19], Botswana [

20], Namibia [

21], Ethiopia [

22,

23], and South Africa [

24,

25]), in South America (e.g., in Nicaragua [

26], Barbados [

27], Brazilian Amazon [

28], and Colombia [

29]), and in Asia (e.g., in Philippines [

30]).

There is a general agreement in the existing literature regarding the potential contribution of CBTs to poverty alleviation and sustainability of tourism industry and local communities (e.g., [

17,

19,

22,

23,

26,

31,

32,

33,

34]. Also, about one of the main challenges of CBTEs: A weak managerial capacity among communities to run these CBTEs [

20,

21,

22,

24,

26,

28,

33]. However, there are also successful cases such as the Community-based ecotourism in Menz Guassa in Ethiopia, where “indigenous community leaders were capable of operating and managing community based ecotourism businesses effectively and inspiring individuals from the local population to participate in the tourism business” [

23].

There are non-profit organizations that have established standards for the management of sustainable destinations, such as “maximize the economic and social benefits of communities and minimize impacts” [

35]. Within these criteria, certain elements of the administrative process have been considered such as organizational management of the destination, monitoring, planning, promotion, and visitor satisfaction, among others [

35]. However, all this has been developed in a general perspective without specifying administrative and financial processes necessary for good enterprise development and permanence.

There are some statements about the relevance of the administrative-financial process of CBTEs. For example, in the Community Tourism Good Practices Manual of the Solidarity Tourism Network of the Napo River Ribiera-REST [

36] (p. 33), it is stated as an administrative criterion, that “the Community Tourism initiative should maintain an efficient administration that allows to know the status of its management and the characteristics of its visitors with a basic accounting of income and expenditures”.

An administrative process cannot only be based on the company’s financial controls as Fayol proposed in the 20th century. Nowadays, the use of four fundamental management principles has been accepted: Planning, implementation, monitoring, and evaluation [

37], whose fulfillment leads to the achievement of business objectives. Within these fundamental principles of management, there are some specific processes, which help to achieve these business purposes, leading to efficiently fulfill the operational cycle of organizations. According to D’Alessio Ipinza [

38], it is a model that accurately represents how the company works, without considering that some areas are more important than others, since all of them are significant for its correct functionality.

Until now, there are some proposals from CBTEs for a general management model. Despite the fact that a few of these enterprises were developed by non-governmental organizations, they do not have a full community adaptation process. As such, there was inadequate implementation follow-up to assess long-term results. In consequence, many Community Tourism Centers become extinct (or inactive), which shows how important is to have optimal organizational structure as the key to success [

39] for any type of undertaking.

In a former interview with the FEPTCE president, Galindo Parra (2017) stated that: “most CBTEs started their activities spontaneously and supported by non-governmental organizations (NGOs) with human, physical and economic resources, so they could carry out these community projects, principally to promote cultural conservation and authenticity through the provision of community tourism services”. However, the NGOs have not continuously monitored the development of these undertakings, which, in many cases, leads to these centers’ mismanagement or even their extinction.

The paper is structured as follows. After this introduction,

Section 1 describes the geographical area (provinces of Pichincha, Napo, and Imbabura). On the other hand,

Section 2 describes the research methodology.

Section 3 includes the results of the research which are discussed in

Section 4. Finally,

Section 5 summarizes and concludes.

Description of the Geographic Area

Ecuador is a country located in the continent of South America, on the equatorial line, bound on the north by Colombia, on the south and east by Peru, and on the west by the Pacific Ocean, with an area of 283,520 km

2. According to the last population census (2010), Ecuador has a population of 14,483.499 inhabitants, distributed among mestizos (71.9%), Afro-Ecuadorians (7.2%), indigenous (7%), whites (6.1%), and montubios (7.4%) [

40]. It has a varied climate due to the three geographical areas, which divide the country: Highlands (Andes mountains), Coast (on the Pacific coast), Eastern (Amazon jungle), and the Insular region (Galapagos Islands) [

41]. Depending on the area and its altitude, the climates range from tropical to cold, with two defined seasons in all regions, such as wet and dry. Furthermore, it has an extensive mountainous area defined by the Andes Mountains and a large fluvial network crossing all over the territory.

Ecuador is a multi-ethnic and pluricultural country composed by 24 provinces, and 221 cantons; two of which, Quito and Cuenca, have been recognized as Cultural Heritage of Humanity by UNESCO. This recognition is also held by the Galapagos Islands, and Sangay National Park. Within the indigenous population, 13 nationalities and 14 villages have been identified [

42], with specific culture, tradition, dialect, and economy, located between the three regions, further diversifying the appeal that Ecuador can offer to the world.

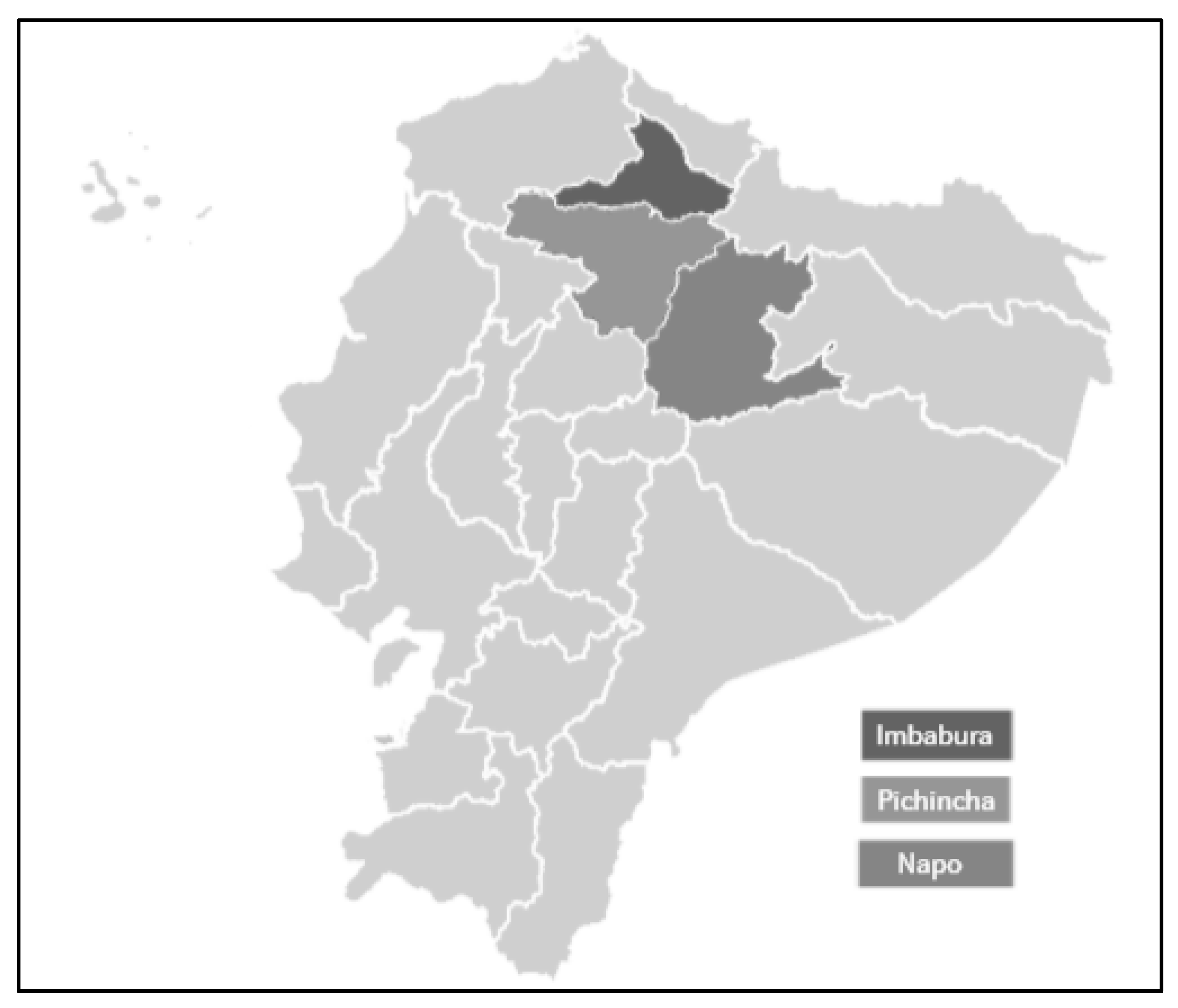

Three provinces have been selected for this research: Pichincha, Napo, and Imbabura, because of their proximity to the capital (Quito), where the Universidad Central del Ecuador mainly develops its academic, scientific, and outreach activities. In addition, they are the provinces with a high number of CBTEs established according to the database provided by the FEPTCE.

Pichincha is a province located in the highlands in the central north area of the country (

Figure 1), divided into eight cantons, each with its urban and rural parishes. It has an average altitude of 2816 meters above sea level, a varied climate depending on the altitude, and the city of Quito is its capital [

43]. It has great flora and fauna diversity and important natural and cultural beauties, making it an attractive province to visit.

Imbabura, like Pichincha province, is located in the highlands in the central north area of the country (

Figure 1). The climate types are hot and dry in the Chota Valley passing through to a temperate climate in the cantonal capitals to cold, high in the mountains of the Imbabura and Cotacachi hills, to hot and humid in the Intag and Lita sector. Imbabura is divided into six cantons, Imabura being its capital. It has two important reserves (Cayambe-Coca Ecological Reserve and Cotacachi-Cayapas Ecological Reserve) with high biodiversity, represented by numerous plant and animal species and genetic resources. The province also has abundant water and mineral resources [

44].

Napo is located partly in the Ecuadorian Amazon region and partly in the Andean slopes, reaching up to the Amazon plains (

Figure 1). It is a place marked by high biological diversity, with five cantons, and Tena is its capital. The climate varies according to the diversity of the geoforms present and most of the area is subject to a large annual excess of precipitation. It is a place to learn about the customs and traditions of the Amazonian Quichua people who maintain their way of life [

45].

Currently, tourism is considered an important sector inside the sustainable development of territories and is a complicated growing global phenomenon, which provides benefits for both travelers and destinations [

46]. According to the research carried out by Cabanilla [

14], the CBTEs are located throughout the Ecuadorian zones, with 44.44% of them in the provinces of Imbabura, and Pichincha, in the highlands, as well as Manabí, and Santa Elena. The parishes with the highest concentration of these enterprises are in the province of Napo.

4. Discussion

4.1. Performance of Administrative and Financial Processes by Province

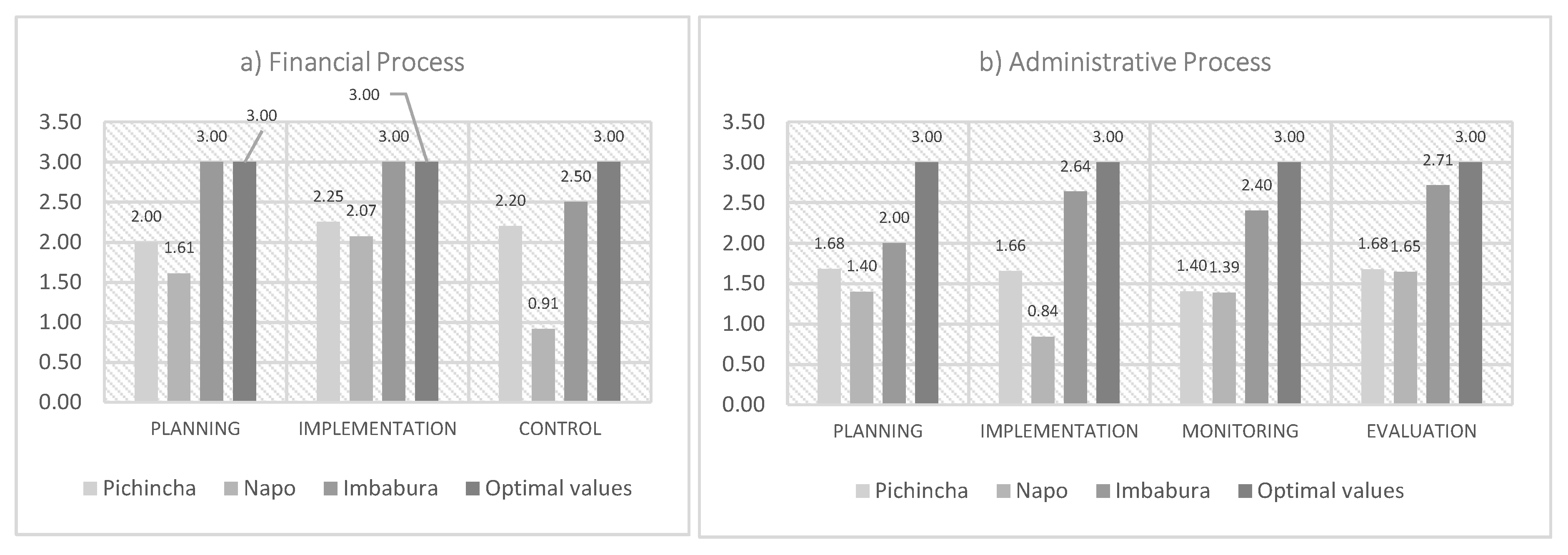

According to the collected data, it was verified that not all tourism enterprises accomplish the Community-Based Tourism Enterprise status, and that is why a sampling of 28 enterprises for this diagnosis was used, as previously stated. Once the interviewers obtained the necessary information to fill each CBTE’s matrix through the community leader’s information, the data were analyzed, and the results of each province were compared with the optimum values to determine the real administrative and financial behavior inside the CBTEs.

In Imbabura’s case, the CBTE selected for the diagnosis is a tourism operator named Runa Tupary founded in 2000 with FEPTCE active members and Imbabura’s community leaders. This tourism operator organizes tourism activities inside four communities and distributes a small portion of the gains between them. Imbabura is the province which is closest to the optimum values, especially inside the financial process (

Figure 5), but it is because this particular venture has a more corporate than communitarian structure, creating a lack of knowledge about the management of economic resources and questioning the efficiency of tourism regulatory bodies. The model used by Runa Tupary is an applicable model, as long as each CBTE manages its own accounting system, a situation that currently does not hold. There are feasible management models such as the creation of a community-based tourism operator, which is responsible for the administrative and financial management of the related enterprises, but these should be applied according to the needs of each community and especially considering the number of families which are part of it.

In the province of Pichincha, four CBTEs were identified: Asociación Camino El Cóndor Cariacu, Asociación Para el Desarrollo de las Comunidades- La Chimba, Camino al Cóndor Paquiestancia, and Corporación Micro-empresaria Yunguilla. The results in these four CBTEs showed that the financial and administrative models are not adequate for theirs needs, and in some cases even because they do not have any model to manage their enterprises. Moreover, as verified, tourism is considered a complementary activity inside their internal economies, so that it is why only a small portion of the budget is invested in tourism services improvement. In addition to this, according to one community leader Vinicio Kilo (2018), CBTEs do not work because there is low interest among the communities’ members and a growth in movement of young people to other provinces.

Napo province is considered one of the provinces where the CBTEs are most established in Ecuador [

62]. After the census, 23 centers were selected for the present diagnosis, from which eight have the Tourism Ministry certification as Community-Based Tourism Enterprises. Despite this, Napo becomes the province with the lowest values compared to the optimum values because, as observed, neither the communities nor the Ministry give enough importance to the administrative and financial processes in the enterprise’s constitution. Moreover, there is no training on these topics and that is why some enterprises are in a critical economic situation despite the fact that tourism is the only economic activity inside some communities.

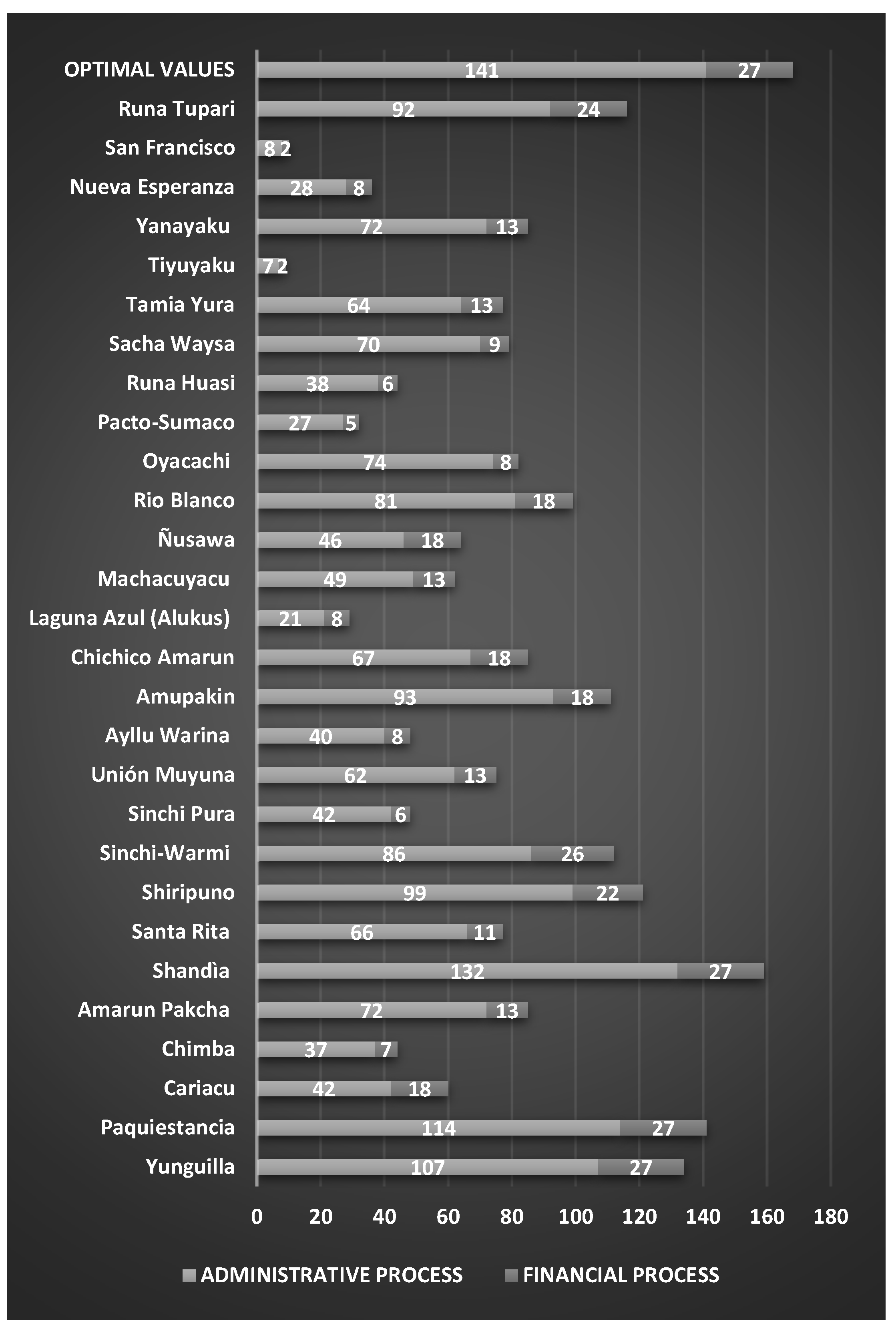

4.2. Performance of Administrative and Financial Processes by CBTE

As formerly stated, the results were obtained by the diagnosis of 28 CBTEs, one in Imabura, four in Pichincha, and 23 in Napo. This section will not discuss the case of Imbabura province, because the situation of these enterprises was already clarified in the previous section.

The results obtained in the matrix show that, within the administrative processes (

Table 3), the companies do not consider as a priority nor count on: strategic and operative plans, market surveys, competition landscape. Nor do they implement the guidelines governing the procedures of every enterprise, such as mission, vision, values, policies, etc. Other unnoticed elements are cost analysis and ongoing employee training, which are important elements in a successful business.

Within the implementation elements, it is observed that most of the processes are not developed within the companies, such as implemented procedures, process manual, marketing plan, employee recruitment process, defined jobs, job skills, employee IESS affiliation, employee coordination, supplier analysis, supplier qualification systems. All these processes are important elements, which help the organization towards good performance.

On the other hand, apart from the elements of monitoring and evaluation, which are mostly being implemented within these companies, there are others that are important such as the post-sale relationship and the use of new technologies such as social networks for promotion, which are not being developed. This, in a certain way, leads these companies neither to be known nationally and internationally nor to build a long-term relationship with current customers.

Table 9 and

Table 10 show the similarities and differences between the administrative and financial diagnosis of CBTEs.

5. Conclusions

This document contributes to create interest and knowledge about the management of administrative and financial processes of Community-Based Tourism Enterprises, since currently there is no work on this topic. Many researches are focused on studying and analyzing environmental impacts, community participation, anthropological issues, or economic and social impacts of tourism enterprises within communities, but there is no clear interest in knowing how these enterprises are managed and if they do it properly, leaving a gap in knowledge, since business success depends on the adequate management of financial and administrative processes.

Another contribution of this research is to publish the administrative and financial development of the CBTEs with the intention of generating awareness about the importance of implementing these processes in community enterprises. In addition, this paper can help to generate interest in the academy to continue carrying out research of this type, mainly in the community area, which has been left aside.

The methodology used in this research can be used in all types of tourist and/or commercial enterprises of small and medium size. This is because the diagnostic matrix has all the basic administrative and financial elements that every business needs to function correctly. The main limitations exhibited by this type of research is to make contact with the leaders of the community centers and to gain the trust of these leaders in order to obtain as sincere as possible answers when gathering the information included in the diagnostic matrix.

Currently, Community-Based Tourism Enterprises do not have a technical document that allows them to adequately implement the administrative and financial processes in their enterprises, and this is one of the factors that causes some to disappear and others to be in critical condition. In research about China, the results confirm that the financial performance of tourism enterprises can serve as a leading indicator in order to understand the overall business development [

63]. It must also be considered that management of tourism operators requires different plans of action because of the peculiarities between these enterprises, especially since problems often arise in the strategic and operational planning processes [

64]. The administrative and financial management inside CBTEs should be much more case specific, since there are other important elements to be considered, such as culture and the socio-economic structure of communities, so that this kind of analysis helps to understand how these enterprises manage these processes.

It was identified that a certification granted by the Ministry of Tourism does not guarantee the optimal functioning of these enterprises, because the administrative and financial issues are not considered within the certification requirements.

It is important to mention that currently community-based tourism represents the secondary source of income within the communities as can also be seen in the research carried out by Manyara and Jones [

17], Lapeyre [

21], and Vargas [

31]. Therefore, this activity itself could not maintain the economies of the families because it represents a low economic income, which can be seen in other studies such as the case of Nicaragua carried out by Zapata et al. [

26]. This is why community members are mainly engaged in agricultural and livestock activities.

The participation of government entities is important, especially the Ministry of Tourism with permanent training in administrative and financial issues. In this way, the CBTE can have better organization, planning, and implementation in the use of its resources.

It was clear that CBTEs have not designed, and much less implemented, the administrative and financial processes that help them to have proper management of the enterprises, but it could be evidenced that they have considered trainings, academic studies, and the learning of new technologies to improve their quality and to be competitive.

With these results, it is necessary to design a standard administrative and financial model for CBTEs that is easy and simple to use, which considers the main elements of these processes and guarantees good business management. This can be seen in the studies carried out by Salazar et al. [

65] and García et al. [

66] on the importance of implementing administrative and financial processes within the management and administration of business resources.