Consumer Behavior towards Regional Eco-Labels in Slovakia

Abstract

:1. Introduction

1.1. Characterization of Eco-Labeling

1.2. Characterization of Regional Eco-Labeling in Slovakia

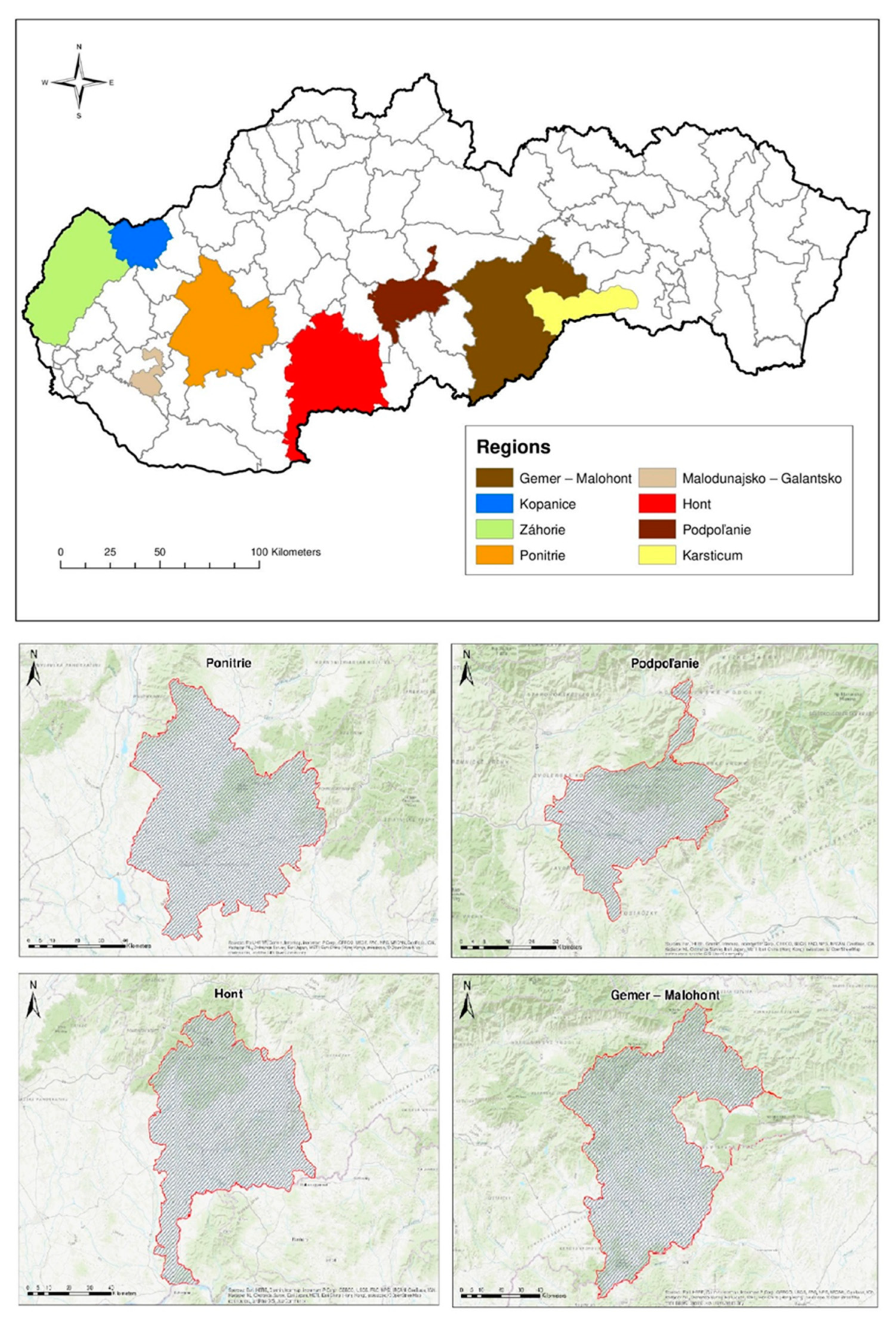

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results and Discussion

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Prieto-Sandoval, V.; Alfaro, J.A.; Mejía-Villa, A.; Ormazabal, M. ECO-labels as a multidimensional research topic: Trends and opportunities. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 135, 806–818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bratt, C.; Hallstedt, S.; Robèrt, K.H.; Broman, G.; Oldmark, J. Assessment of eco-labelling criteria development from a strategic sustainability perspective. J. Clean. Prod. 2011, 19, 1631–1638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Clancy, G.; Fröling, M.; Peters, G. Ecolabels as drivers of clothing design. J. Clean. Prod. 2015, 99, 345–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voinea, L.; Vrânceanu, D.M.; Filip, A.; Popescu, D.V.; Negrea, T.M.; Dina, R. Research on food behavior in romania from the perspective of supporting healthy eating habits. Sustainability 2019, 11, 5255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Miranda-Ackerman, M.A.; Azzaro-Pantel, C. Extending the scope of eco-labelling in the food industry to drive change beyond sustainable agriculture practices. J. Environ. Manag. 2017, 204, 814–824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Leroux, E.; Pupion, P.C. Factors of adoption of eco-labelling in hotel industry. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2018, 129, 194–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakravarthy, Y.; Potdar, A.; Singh, A.; Unnikrishnan, S.; Naik, N. Role of ecolabeling in reducing ecotoxicology. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2016, 134, 383–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feldmann, C.; Hamm, U. Consumers’ perceptions and preferences for local food: A review. Food Qual. Prefer. 2015, 40, 152–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozaki, R. Adopting sustainable innovation: What makes consumers sign up to green electricity? Bus. Strategy Environ. 2011, 20, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Céline, M.; Llerena, D. Green Consumer Behaviour: An Experimental. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2011, 420, 408–420. [Google Scholar]

- Sammer, K.; Wüstenhagen, R. The influence of eco-labelling on consumer behaviour—Results of a discrete choice analysis for washing machines. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2006, 15, 185–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Thompson, D.W.; Anderson, R.C.; Hansen, E.N.; Kahle, L.R. Green segmentation and environmental certification: Insights from forest products. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2010, 19, 319–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, A. What’s in it for the customers? Successfully marketing green clothes. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2001, 10, 317–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rex, E.; Baumann, H. Beyond ecolabels: What green marketing can learn from conventional marketing. J. Clean. Prod. 2007, 15, 567–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Cerri, J.; Testa, F.; Rizzi, F. The more I care, the less I will listen to you: How information, environmental concern and ethical production influence consumers’ attitudes and the purchasing of sustainable products. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 175, 343–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eco-Label Index. Available online: http://www.ecolabelindex.com/ecolabels/ (accessed on 24 October 2019).

- Van Ittersum, K.; Meulenberg, M.T.G.; van Trijp, H.C.M.; Candel, M.J.J.M. Consumers’ appreciation of regional certification labels: A pan-European study. J. Agric. Econ. 2007, 58, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Ferrín, P.; Calvo-Turrientes, A.; Bande, B.; Artaraz-Miñón, M.; Galán-Ladero, M.M. The valuation and purchase of food products that combine local, regional and traditional features: The influence of consumer ethnocentrism. Food Qual. Prefer. 2018, 64, 138–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bingen, J. Labels of origin for food, the new economy and opportunities for rural development in the US. Agric. Hum. Values 2012, 29, 543–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilbery, B.; Maye, D. Marketing sustainable food production in Europe: Case study evidence from two Dutch labelling schemes. Tijdschr. Voor Econ. Soc. Geogr. 2007, 98, 507–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krnáčová, P.; Kirnová, L. Regionálne produkty z pohľadu spotrebiteľov (Regional products from a consumer perspective). Studia Commer. Bratisl. 2015, 8, 4. [Google Scholar]

- Hrubalová, L. Regionálne produkty v rozvoji regiónu Záhorie (Regional products in the development of the Záhorie region) (in Slovak). Reg. Rozv. Mezi Teorií Praxí 2017, 3, 72–82. [Google Scholar]

- Jaďuďová, J.; Marková, I.; Hroncová, E.; Vicianová, J.H. An assessment of regional sustainability through quality labels for small farmers’ products: A Slovak case study. Sustainability 2018, 10, 1273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Jaďuďová, J.; Marková, I.; Vicianová, J.H.; Bohers, A.; Murin, I. Study of consumer preferences of regional labeling. Slovak case study. Eur. Countrys. 2018, 10, 429–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sarstedt, M.; Mooi, E. Concise Guide to Market Research: The Process, Data, and Methods Using IBM SPSS Statistics, 1st ed.; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Srinivasan, A.K.; Blomquist, G.C. Ecolabeled paper towels: Consumer valuation and expenditure analysis. J. Environ. Manag. 2009, 90, 314–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cai, Z.; Xie, Y.; Aguilar, F.X. Eco-label credibility and retailer effects on green product purchasing intentions. Forest Policy Econ. 2017, 80, 200–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schumacher, I. Ecolabeling, consumers’ preferences and taxation. Ecol. Econ. 2010, 69, 2202–2212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Telligman, A.L.; Worosz, M.R.; Bratcher, C.L. “Local” as an indicator of beef quality: An exploratory study of rural consumers in the southern U.S. Food Qual. Prefer. 2017, 57, 41–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Nicolosi, A.; Laganà, V.R.; Laven, D.; Marcianò, C.; Skoglund, W. Consumer habits of local food: Perspectives from northern Sweden. Sustainability 2019, 11, 6715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Chalupová, M.; Prokop, M.; Rojík, S. Regional Food Preference and Awareness of Regional Labels in Vysočina Region (Czech Republic). Eur. Countrys. 2016, 8, 109–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Laroche, M.; Bergeron, J.; Barbaro-Forleo, G. Targeting consumers who are willing to pay more for environmentally friendly products. J. Consum. Mark. 2001, 18, 503–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Maeve, H.; Mcintyre, B. The use of regional imagery in the marketing of quality products and services. Irish Mark. Rev. 2000, 13, 19–26. [Google Scholar]

- Verbeke, W. Food quality policies and consumer interests in the EU. EAAP Sci. Ser. 2012, 133, 13–22. [Google Scholar]

| Basic Sample | Selected Sample | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Abs. Frequency | Rel. Frequency (%) | Abs. Frequency | Rel. Frequency (%) | |

| Gender | ||||

| Male | 314,428 | 49 | 320 | 48 |

| Female | 327,260 | 51 | 349 | 52 |

| Total | 641,688 | 100 | 669 | 100 |

| Region | ||||

| Ponitrie | 346,211 | 54 | 359 | 54 |

| Hont | 125,818 | 20 | 128 | 19 |

| Podpoľanie | 84,918 | 13 | 81 | 12 |

| Gemer-Malohont | 84,741 | 13 | 101 | 15 |

| Total | 64,688 | 100 | 669 | 100 |

| Cluster 1 | Cluster 2 | Cluster 3 | Cluster 4 | Cluster 5 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Relative share of cluster | 60.7% | 7.7% | 8.4% | 19.3% | 3.9% |

| Purchase of domestic products | 100.0% a | 100.0% a | 94.3% a | 100.0% a | 100.0% b |

| Purchase of regional products | 100.0% a | 100.0% a | 100.0% b | 100.0% a | 100.0% b |

| Knowledge of eco-labeling | 100.0% a | 100.0% b | 77.1% a | 100.0% a | 100.0% b |

| Composition of product | 100.0% a | 59.4% b | 65.7% a | 100.0% b | 50.0% a |

| Cluster 1 (%) | Cluster 2 (%) | Cluster 3 (%) | Cluster 4 (%) | Cluster 5 (%) | Chi-Square | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | 27.478 | 0.000 | |||||

| Male | 27.0 | 3.4 | 5.5 | 7.0 | 3.9 | ||

| Female | 33.7 | 4.3 | 2.9 | 12.3 | 0.0 | ||

| Age | 105.504 | 0.000 | |||||

| 18–25 | 13.3 | 1.0 | 1.9 | 7.0 | 1.4 | ||

| 26–61 | 44.8 | 2.2 | 5.3 | 9.2 | 0.7 | ||

| 62 and over | 2.7 | 4.6 | 1.2 | 3.1 | 1.7 | ||

| Education | 70.735 | 0.000 | |||||

| Primary | 1.9 | 0.0 | 0.2 | 1.7 | 1.0 | ||

| Secondary | 20.5 | 5.1 | 6.0 | 11.3 | 2.7 | ||

| University (1st, 2nd) | 35.7 | 1.9 | 1.7 | 5.8 | 0.2 | ||

| University (3rd) | 2.7 | 0.7 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.0 | ||

| Employment | 149.226 | 0.000 | |||||

| Employed | 46.0 | 2.4 | 3.6 | 8.7 | 0.0 | ||

| Unemployed | 1.4 | 1.0 | 1.9 | 3.1 | 0.5 | ||

| Retired | 2.2 | 3.6 | 1.0 | 2.9 | 1.7 | ||

| On maternity leave | 4.3 | 0.2 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | ||

| Student | 6.7 | 0.5 | 1.9 | 4.6 | 1.7 | ||

| Monthly income | 69.489 | 0.000 | |||||

| <EUR 350 | 14.5 | 1.0 | 2.9 | 10.1 | 1.7 | ||

| EUR 351–550 | 15.2 | 3.6 | 2.4 | 6.7 | 1.4 | ||

| EUR 551–750 | 18.1 | 0.5 | 2.7 | 1.0 | 0.2 | ||

| EUR 751–950 | 6.7 | 1.9 | 0.2 | 1.0 | 0.5 | ||

| >EUR 950 | 6.3 | 0.7 | 0.2 | 0.5 | 0.0 | ||

| Number of children | 162.071 | 0.000 | |||||

| 0 | 34.0 | 1.0 | 2.4 | 15.2 | 1.9 | ||

| 1 | 12.8 | 1.2 | 1.7 | 1.7 | 0.0 | ||

| 2 | 11.8 | 1.7 | 2.4 | 1.7 | 0.5 | ||

| 3 | 1.9 | 3.9 | 0.7 | 0.5 | 1.0 | ||

| 4 | 0.2 | 0.0 | 1.2 | 0.2 | 0.5 | ||

| Locality | 25.203 | 0.000 | |||||

| Urban | 33.3 | 3.6 | 2.9 | 5.8 | 0.5 | ||

| Rural | 27.5 | 4.1 | 5.5 | 13.5 | 3.4 | ||

| Region | 79.510 | 0.000 | |||||

| Ponitrie | 34.9 | 3.6 | 1.4 | 12.0 | 1.4 | ||

| Hont | 10.1 | 2.4 | 2.4 | 1.2 | 0.5 | ||

| Podpoľanie | 10.6 | 0.2 | 0.7 | 4.1 | 0.0 | ||

| Gemer-Malohont | 5.1 | 1.4 | 3.9 | 1.9 | 1.9 |

| Cluster 1 (%) | Cluster 2 (%) | Cluster 3 (%) | Cluster 4 (%) | Cluster 5 (%) | Chi-Square | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Regional labeling in shops | 27.840 | 0.000 | |||||

| No | 30.4 | 4.2 | 3.6 | 8.6 | 3.6 | ||

| Yes | 32.9 | 0.3 | 4.5 | 12.0 | 0.0 | ||

| Regional labeling at public events | 39.479 | 0.000 | |||||

| No | 16.8 | 3.4 | 2.0 | 4.7 | 4.2 | ||

| Yes | 44.7 | 3.9 | 6.7 | 13.7 | 0.0 | ||

| Knowledge of regional labeling | 207.963 | 0.000 | |||||

| No | 1.1 | 1.9 | 1.1 | 0.3 | 3.7 | ||

| Yes | 62.7 | 5.6 | 5.6 | 18.1 | 0.0 | ||

| Product price | 27.040 | 0.000 | |||||

| No | 28.2 | 1.2 | 2.2 | 4.3 | 2.2 | ||

| Yes | 32.5 | 6.5 | 6.3 | 14.9 | 1.7 | ||

| Buying a specific product | 69.148 | 0.000 | |||||

| No | 26.0 | 5.5 | 5.3 | 17.8 | 3.1 | ||

| Yes | 34.7 | 2.2 | 3.1 | 1.4 | 0.7 | ||

| Repeat purchase of regional labels | 26.776 | 0.000 | |||||

| No | 2.2 | 1.0 | 1.7 | 1.9 | 1.2 | ||

| Yes | 58.6 | 6.7 | 6.7 | 17.3 | 2.7 | ||

| Travel for the product | 37.783 | 0.000 | |||||

| No | 39.0 | 5.3 | 6.5 | 19.0 | 3.1 | ||

| Yes | 21.7 | 2.4 | 1.9 | 0.2 | 0.7 | ||

| Frequency of purchase | 41.648 | 0.000 | |||||

| Once per week | 3.9 | 1.2 | 1.9 | 5.1 | 1.4 | ||

| Twice per week | 20.5 | 3.6 | 1.9 | 4.1 | 1.4 | ||

| Three times per week | 19.5 | 1.9 | 2.4 | 5.5 | 0.2 | ||

| Four or more times per week | 16.9 | 1.0 | 2.2 | 4.6 | 0.7 | ||

| Promotion of products | 151.161 | 0.000 | |||||

| Newspaper | 2.4 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 1.9 | 0.5 | ||

| TV | 9.2 | 0.7 | 1.2 | 2.2 | 0.2 | ||

| Radio | 0.5 | 1.7 | 0.5 | 0.0 | 1.0 | ||

| Leaflets | 6.3 | 3.1 | 2.2 | 8.4 | 1.0 | ||

| Personal experience | 29.4 | 1.0 | 2.4 | 5.5 | 0.0 | ||

| Presentation | 8.0 | 0.0 | 0.7 | 0.5 | 0.0 | ||

| Internet | 5.1 | 0.7 | 1.0 | 0.7 | 1.2 |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Jaďuďová, J.; Badida, M.; Badidová, A.; Marková, I.; Ťahúňová, M.; Hroncová, E. Consumer Behavior towards Regional Eco-Labels in Slovakia. Sustainability 2020, 12, 5146. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12125146

Jaďuďová J, Badida M, Badidová A, Marková I, Ťahúňová M, Hroncová E. Consumer Behavior towards Regional Eco-Labels in Slovakia. Sustainability. 2020; 12(12):5146. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12125146

Chicago/Turabian StyleJaďuďová, Jana, Miroslav Badida, Anna Badidová, Iveta Marková, Miriam Ťahúňová, and Emília Hroncová. 2020. "Consumer Behavior towards Regional Eco-Labels in Slovakia" Sustainability 12, no. 12: 5146. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12125146

APA StyleJaďuďová, J., Badida, M., Badidová, A., Marková, I., Ťahúňová, M., & Hroncová, E. (2020). Consumer Behavior towards Regional Eco-Labels in Slovakia. Sustainability, 12(12), 5146. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12125146