The Relationship between Green Country Image, Green Trust, and Purchase Intention of Korean Products: Focusing on Vietnamese Gen Z Consumers

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review and Hypotheses

2.1. Gen Z Consumers in Vietnam

2.2. Green Country Image

2.3. Green Trust

3. Methodology and Measurement

3.1. Data Collection and Sample

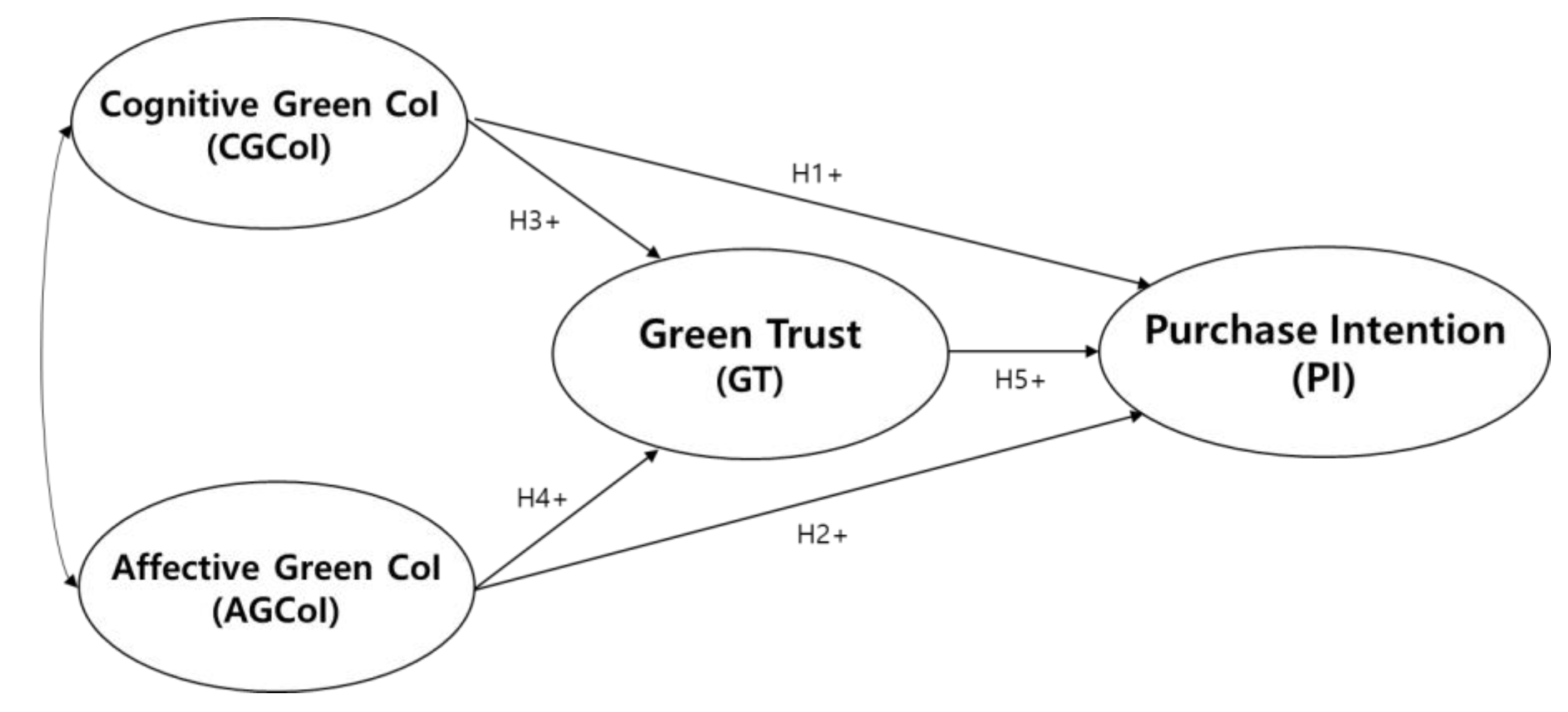

3.2. Study Model

3.3. Definitions and Measurements of the Constructs

3.4. Data Analysis Methodology

4. Empirical Results

4.1. Validity and Reliability of Measurement Instruments

4.2. Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) Test

4.3. Correlation Analysis

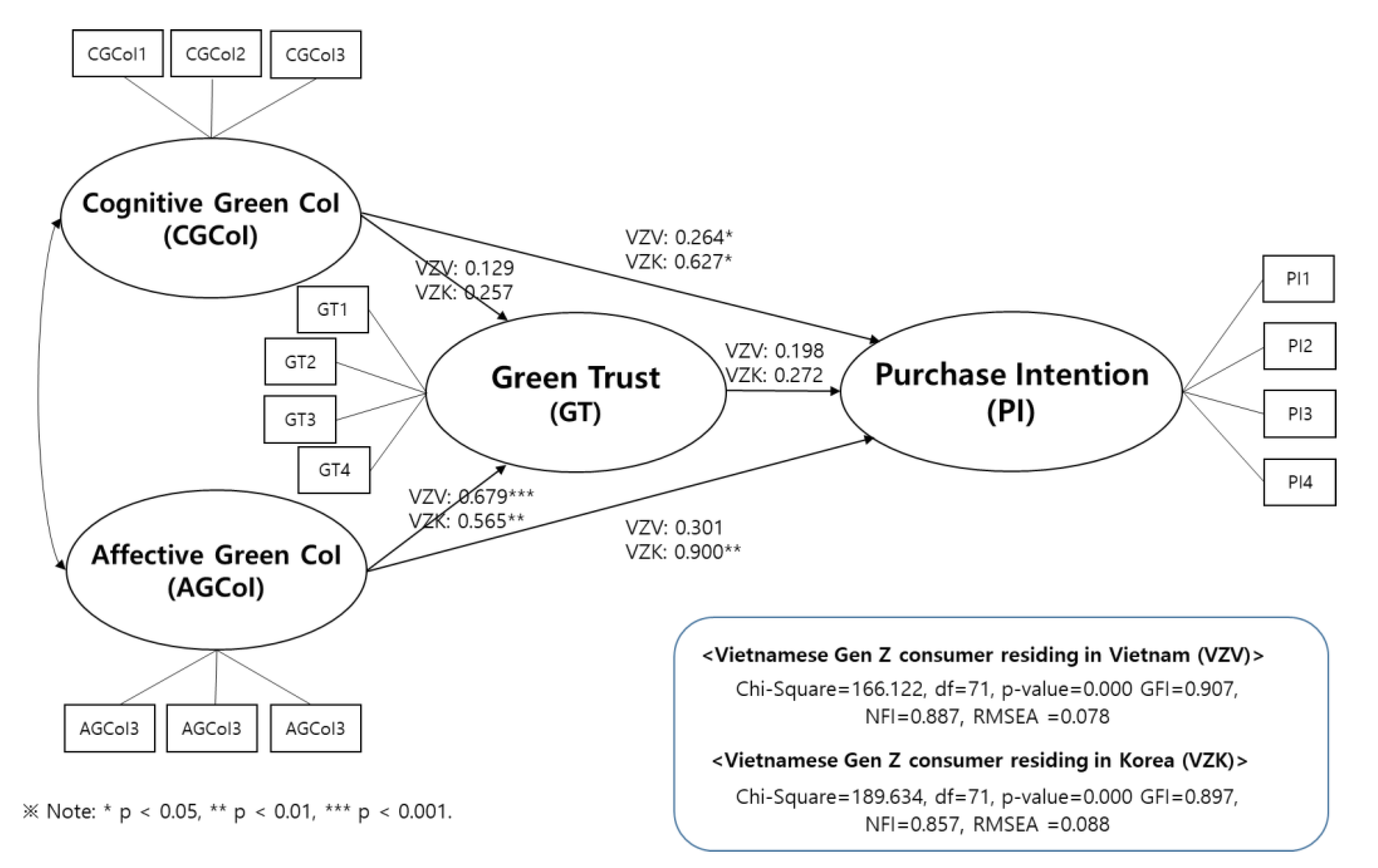

4.4. Results of SEM Analysis

4.5. Comparison of SEM Analysis Results between VZV and VZK

5. Conclusion and Implications

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- IMF. Vietnam’s Development Success Story and the Unfinished SDG Agenda, International Monetary Fund, IMF Working Paper: Asia Pacific Department. 2020. Available online: file:///C:/Users/kate%20lee/Downloads/wpiea2020031-printpdf.pdf (accessed on 23 March 2020).

- ADB. Vietnam Environment and Climate Change Assessment; Asian Development Bank: Tokyo, Japan, 2013; Available online: https://www.adb.org/sites/default/files/institutional-document/33916/files/viet-nam-environment-climate-change.pdf (accessed on 27 December 2019).

- Jung, J.W.; Kim, J.K. Background and Prospect of Export Enhancement in Vietnam; KIEP: Seoul, Korea, 2018; pp. 1–28. Available online: http://www.kiep.go.kr/sub/view.do?bbsId=KiepBaseLine&nttId=201282 (accessed on 26 December 2019).

- Dekhili, S.; Achabou, M.A. Towards Greater Understanding of Ecolabel Effects: The Role of Country of Origin. J. Appl. Bus. Res. (JABR) 2014, 30, 433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurmangali, Z. Literature Review: The Country of Origin Image Affecting Consumers’ Purchase Decision. Int. J. Eng. Manag. Res. 2019, 9, 128–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yasin, N.M.; Noor, M.N.; Mohamad, O. Does image of country-of-origin matter to brand equity? J. Prod. Brand Manag. 2007, 16, 38–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hien, N.; Phuong, N.; Tran, T.; Thang, L. The effect of country-of-origin image on purchase intention: The mediating role of brand image and brand evaluation. Manag. Sci. Let. 2020, 10, 1205–1212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yossie, R.; Muhammad, D.T.P.N. Information search and intention to purchase: The role of country image, product knowledge, and product involvement. Int. J. Info. Bus. Manag. 2019, 11, 130–141. [Google Scholar]

- Verlegh, P.W.J.; Steenkamp, J.-B.E. A review and meta-analysis of country-of-origin research. J. Econ. Psychol. 1999, 20, 521–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souiden, N.; Amara, N.; Chaouali, W. Optimal image mix cues and their impacts on consumers’ purchase intention. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2020, 54, 102011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laroche, M.; Papadopoulos, N.; Heslop, L.A.; Mourali, M. The influence of country image structure on consumer evaluations of foreign products. Int. Mark. Rev. 2005, 22, 96–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dickens, C.; Smakhtin, V.; McCartney, M.; O’Brien, G.; Dahir, L. Defining and Quantifying National-Level Targets, Indicators and Benchmarks for Management of Natural Resources to Achieve the Sustainable Development Goals. Sustainability 2019, 11, 462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roth, K.P.; Diamantopoulos, A. Advancing the country image construct. J. Bus. Res. 2009, 62, 726–740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bassiouni, D.H.; Hackley, C. ’Generation Z’ children’s adaptation to digital consumer culture: A critical literature review. J. Cust. Behav. 2014, 13, 113–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gale, S.F. Forget millennials: Are you ready for generation Z? Chief Learn. Off. 2015, 14, 38. Available online: www.clomedia.com/2015/07/07/forget-gen-y-are-you-ready-for-gen-z (accessed on 21 September 2019).

- Nielsen. Generation Z as Online Shoppers: Exactly How Engaged are They? The Nielsen Company (US): Hong Kong, 2018; Available online: http://www.nielsen.com/hk/en/insights/article/2018/generation-z-as-online-shoppers-exactly-how-engaged-are-they/ (accessed on 20 August 2019).

- Financial Times. Younger Consumers Drive Shift to Ethical Products; The Financial Times (UK): London, UK, 2018; Available online: https://www.ft.com/content/8b08bf4c-e5a0-11e7-8b99-0191e45377ec (accessed on 23 March 2020).

- Smith, A.M.; O’Sullivan, T. Environmentally responsible behavior in the workplace: An internal social marketing approach. J. Mark. Manag. 2012, 28, 469–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deloitte. The Vietnam Consumer Survey: An Accelerating Momentum; Deloitte (UK): London, UK, January 2020; Available online: https://www2.deloitte.com/content/dam/Deloitte/sg/Documents/consumer-business/sea-cb-vietnam-consumer-survey-2020.pdf (accessed on 23 March 2020).

- VietNamNet Global. Korean Investors See VN as ‘Most Important’ SE Asian Market. 2019. Available online: https://vietnamnet.vn/en/business/korean-investors-see-vn-as-most-important-se-asian-market-531245.html (accessed on 23 March 2020).

- The World Bank. Country Profile: Vietnam, World Bank Group (USA): Washington, DC, USA, 2018. Available online: https://data.worldbank.org/country/vietnam (accessed on 24 March 2020).

- De Koning, J.; Crul, M.R.M.; Wever, R.; Brezet, J.C. Sustainable consumption in Vietnam: An explorative study among the urban middle class. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2015, 39, 608–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, N.; Nguyen, H.V.; Lobo, A.; Son, D.T. Encouraging Vietnamese Household Recycling Behavior: Insights and Implications. Sustainability 2017, 9, 179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, N.; Lobo, A.; Nguyen, H.L.; Phan, T.T.H.; Cao, T.K. Determinants influencing conservation behaviour: Perceptions of Vietnamese consumers. J. Consum. Behav. 2016, 15, 560–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Y.; Qin, Z.; Yuan, Q. The Impact of Eco-Label on the Young Chinese Generation: The Mediation Role of Environmental Awareness and Product Attributes in Green Purchase. Sustainability 2019, 11, 973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furlow, N.E.; Knott, C. Who’s reading the label? Millennials’ use of environmental product labels. J. Appl. Bus. Econ. 2009, 10, 1–12. Available online: http://www.digitalcommons.www.na-businesspress.com/JABE/Jabe103/FurlowWeb.pdf (accessed on 16 September 2019).

- Holman, J. Generation Z willing to pay more for eco-friendly products. Bloomberg, Business, 2020.01. Available online: https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2020-01-14/generation-z-willing-to-pay-more-for-eco-friendly-products? (accessed on 2 April 2020).

- Su, C.-H.; Tsai, C.-H.; Chen, M.-H.; Lv, W.Q.; Su, T.; Chen Lv, U.S. Sustainable Food Market Generation Z Consumer Segments. Sustainability 2019, 11, 3607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jain, S.K.; Kaur, G. Role of Socio-Demographics in Segmenting and Profiling Green Consumers. J. Int. Consum. Mark. 2006, 18, 107–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dabija, D.C. Enhancing green loyalty towards apparel retail stores: A cross-generational analysis on an emerging market. J. Open Innov. Technol. Mark. Complex. 2018, 4, 8–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Decision Lab. Genzilla: They’re Coming; Get Ready, Decision Lab (CA): Ho Chi Min City, Vietnam, 2015; pp. 1–65. Available online: https://www.decisionlab.co/download-material-genzilla-vietnam (accessed on 6 April 2020).

- Leonidou, L.; Coudounaris, D.N.; Kvasova, O.; Christodoulides, P. Drivers and Outcomes of Green Tourist Attitudes and Behavior: Sociodemographic Moderating Effects. Psychol. Mark. 2015, 32, 635–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naderi, I.; Van Steenburg, E. Me first, then the environment: Young Millennials as green consumers. Young Consum. 2018, 19, 280–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D?souza, C.; Taghian, M.; Lamb, P.; Peretiatko, R. Green decisions: Demographics and consumer understanding of environmental labels. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2007, 31, 371–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grønhøj, A.; Thøgersen, J. Action speaks louder than words: The effect of personal attitudes and family norms on adolescents’ pro-environmental behaviour. J. Econ. Psychol. 2012, 33, 292–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parker, L.; Watne, T.A.; Brennan, L.; Duong, H.T.; Nguyen, D. Self expression versus the environment: Attitudes in conflict. Young Consum. 2014, 15, 138–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, T.T.H.; Yang, Z.; Nguyen, N.; Johnson, L.W.; Cao, T.K. Greenwash and Green Purchase Intention: The Mediating Role of Green Skepticism. Sustainability 2019, 11, 2653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schooler, R.D. Product Bias in the Central American Common Market. J. Mark. Res. 1965, 2, 394–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nai, I.; Cheah, I.; Phau, I. Revisiting Country Image – Examining the Determinants towards Consumers’ Purchase Intention of High Technological Products. J. Promot. Manag. 2018, 24, 420–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bannister, J.; Saunders, J. UK Consumers’ Attitudes towards Imports: The Measurement of National Stereotype Image. Eur. J. Mark. 1978, 12, 562–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, I.M.; Eroglu, S. Measuring a multi-dimensional construct: Country image. J. Bus. Res. 1993, 28, 191–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kock, F.; Josiassen, A.; Assaf, A.G. Toward a Universal Account of Country-Induced Predispositions: Integrative Framework and Measurement of Country-of-Origin Images and Country Emotions. J. Int. Mark. 2019, 27, 43–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopez, C.; Balabanis, G. Country image appraisal: More than just ticking boxes. J. Bus. Res. 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lascu, D.-N.; Ahmed, Z.U.; Ahmed, I.; Min, T.H. Dynamics of country image: Evidence from Malaysia. Asia Pac. J. Mark. Logist. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Motsi, T. Back to the Future: Revisiting the Foundations of Marketing; Flower, J.G., Weiser, J., Eds.; Society of Marketing Advances: West Palm Beach, FL, USA, 2018; pp. 473–479. [Google Scholar]

- Shimp, T.A.; Sharma, S. Consumer Ethnocentrism: Construction and Validation of the CETSCALE. J. Mark. Res. 1987, 24, 280–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klein, J.G.; Ettenson, R.; Morris, M.D. The Animosity Model of Foreign Product Purchase: An Empirical Test in the People’s Republic of China. J. Mark. 1998, 62, 89–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rai, P. Customer ethnocentrism, animosity and purchase intentions of Chinese products. J. Cont. Res. Manag. 2019, 14, 31–38. Available online: https://search.proquest.com/docview/2278758063?accountid=10533 (accessed on 18 May 2020).

- Dursun, I.; Kabadayı, E.T.; Ceylan, K.E.; Köksal, C.G. Russian Consumers Responses to Turkish Products: Exploring the Roles of Country Image, Consumer Ethnocentrism, and Animosity. Bus. Econ. Res. J. 2019, 10, 499–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chi, H.K.; Kuo, H.C.; Nguyen, B.D.T. Exploring destination image in tourism research through co-citation analysis. J. Eco. Manag. Pers. 2018, 12, 552–560. Available online: https://search.proquest.com/docview/2266935069?accountid=10533 (accessed on 19 May 2020).

- Hahm, J.J.; Tasci, A.D.; Terry, D.B. The Olympic Games’ impact on South Korea’s image. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2019, 14, 100373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.-S. The Drivers of Green Brand Equity: Green Brand Image, Green Satisfaction, and Green Trust. J. Bus. Ethic 2009, 93, 307–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, N.J.; Fong, C.M. Green product quality, green corporate image, green customer satisfaction, and green customer loyalty. Afr. J. Bus. Manag. 2010, 4, 2836. Available online: http://repository.ubaya.ac.id/id/eprint/34995 (accessed on 29 November 2019).

- Mercadé-Melé, P.; Gómez, J.M.; Sousa, M.J. Influence of Sustainability Practices and Green Image on the Re-Visit Intention of Small and Medium-Size Towns. Sustainability 2020, 12, 930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corrigan, J. How a green image can drive Irish export growth. Green. Manag. Int. 1996, 16, 87–95. [Google Scholar]

- Dowling, G.R. Managing your corporate images. Ind. Mark. Manag. 1986, 15, 109–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Widyastuti, S.; Said, M.; Siswono, S. Dian Customer Trust through Green Corporate Image, Green Marketing Strategy, and Social Responsibility: A Case Study. Eur. Res. Stud. J. 2019, XXII, 83–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tariq, M.I.; Crouch, R.; Quester, P.G. A review of the cognitive and affective country-of-origin’s effects and their influence on an organizational attribution of blame post a crisis event: An abstract. In Boundary Blurred: A Seamless Customer Experience in Virtual and Real Spaces. AMSAC 2018. Developments in Marketing Science: Proceedings of the Academy of Marketing Science; Krey, N., Rossi, P., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.-B.; Kwon, K.-J. Examining the Relationships of Image and Attitude on Visit Intention to Korea among Tanzanian College Students: The Moderating Effect of Familiarity. Sustainability 2018, 10, 360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, R.J.; Fishbein, M.; Ajzen, I. Belief, Attitude, Intention and Behavior: An Introduction to Theory and Research. Contemp. Sociol. A J. Rev. 1977, 6, 244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.-K.; Robb, C.A. The Relationship of Country Image, ProductCountry Image, and Purchase Intention of Korean Products: Focusing on Differences among Ethnic Groups in South Africa. J. Korea Trade 2019, 23, 33–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adenan, M.A.; Ali, J.K.; Rahman, D.H.A.A. Country of Origin, Brand Image and High Involvement Product Towards Customer Purchase Intention: Empirical Evidence of East Malaysian Consumer. J. Manaj. dan Kewirausahaan 2018, 20, 63–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, D.T. An Integrated Model of Buyer-Seller Relationships. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 1995, 23, 335–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naudé, P.; Buttle, F. Assessing Relationship Quality. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2000, 29, 351–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geyskens, I.; Steenkamp, J.-B.E.; Scheer, L.K.; Kumar, N. The effects of trust and interdependence on relationship commitment: A trans-Atlantic study. Int. J. Res. Mark. 1996, 13, 303–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moorman, C.; Zaltman, G.; Deshpande, R. Relationships between Providers and Users of Market Research: The Dynamics of Trust within and between Organizations. J. Mark. Res. 1992, 29, 314–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgan, R.M.; Hunt, S.D. The Commitment-Trust Theory of Relationship Marketing. J. Mark. 1994, 58, 20–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doney, P.M.; Cannon, J.P. An Examination of the Nature of Trust in Buyer–Seller Relationships. J. Mark. 1997, 61, 35–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganesan, S. Determinants of Long-Term Orientation in Buyer-Seller Relationships. J. Mark. 1994, 58, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shockley, E.; Neal, T.M.; PytlikZillig, L.M.; Bornstein, B.H. (Eds.) Interdisciplinary Perspectives on Trust: Towards Theoretical and Methodological Integration; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Bartosik-Purgat, M. Country of origin as a determinant of young Europeans‘ buying attitudes — marketing implications. Oeconomia Copernic. 2018, 9, 123–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheung, C.; Lee, M.K. Trust in Internet shopping: A proposed model and measurement instrument. AMCIS 2000 Proceedings 2000, 1, 406. Available online: https://aisel.aisnet.org/amcis2000/406 (accessed on 1 October 2019).

- Gefen, D. E-commerce: The role of familiarity and trust. Omega 2000, 28, 725–737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, N.; Leclerc, A.; Leblanc, G. The Mediating Role of Customer Trust on Customer Loyalty. J. Serv. Sci. Manag. 2013, 6, 96–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ong, C.H.; Salleh, S.M.; Yusoff, R.Z. Brand Experience, Trust Components, and Customer Loyalty: Sustainable Malaysian SME Brands Study. Asian Soc. Sci. 2015, 11, 252–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nuttavuthisit, K.; Thøgersen, J. The Importance of Consumer Trust for the Emergence of a Market for Green Products: The Case of Organic Food. J. Bus. Ethic 2015, 140, 323–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poon, P.; Albaum, G. Consumer Trust in Internet Marketing and Direct Selling in China. J. Relatsh. Mark. 2019, 18, 216–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afridi, S.A.; Gul, S.; Haider, M.; Batool, S. Mediating effect of customers’ trust between the association of corporate social responsibility and customers’ loyalty. Pakistan J. Com. Soc. Sci. (PJCSS) 2018, 12, 214–228. [Google Scholar]

- Flavián, C.; Guinaliu, M.; Torres, E. The influence of corporate image on consumer trust: A comparative analysis in traditional versus internet banking. Internet Res. 2005, 15, 447–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukherjee, A.; Nath, P. A model of trust in online relationship banking. Int. J. Bank Mark. 2003, 21, 5–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gefen, D.; Straub, D.W. Consumer trust in B2C e-Commerce and the importance of social presence: Experiments in e-Products and e-Services. Omega 2004, 32, 407–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, C.; Yan, W.; Scherer, R.F. Understanding managerial behavior in different cultures: A review of instrument translation methodology. Psych. Fac. Pub. 1996, 35. Available online: https://digitalcommons.cedarville.edu/psychology_publications/35 (accessed on 2 September 2019).

- Gall, M.D.; Gall, J.P.; Borg, W.R. Educational Research: An introduction, 8th ed.; Pearson/Allyn & Bacon: Boston, IL, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Byrne, B.M. Structural Equation Modeling with AMOS: Basic Concepts, Applications, and Programming (Multivariate Applications Series); Taylor & Francis Group: New York, NY, USA, 2010; Volume 396, p. 7384. [Google Scholar]

- Crites, S.L.; Fabrigar, L.R.; Petty, R.E. Measuring the Affective and Cognitive Properties of Attitudes: Conceptual and Methodological Issues. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 1994, 20, 619–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badri, M.A.; Davis, D.; Davis, D. A study of measuring the critical factors of quality management. Int. J. Qual. Reliab. Manag. 1995, 12, 36–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.L.; Li, D.; Barnes, B.R.; Ahn, J. Country image, product image and consumer purchase intention: Evidence from an emerging economy. Int. Bus. Rev. 2012, 21, 1041–1051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, P.; Bennett, K.; Heritage, B. SPSS Statistics Version 22: A Practical Guide. Cengage Learning Australia. 2014. Available online: http://researchrepository.murdoch.edu.au/id/eprint/31055 (accessed on 20 January 2020).

- Bentler, P.M. Comparative fit indexes in structural models. Psychol. Bull. 1990, 107, 238–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Milfont, T.L.; Fischer, R. Testing measurement invariance across groups: Applications in cross-cultural research. Int. J. Psychol. Res. 2010, 3, 111–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grewal, R.; Cote, J.A.; Baumgartner, H. Multicollinearity and Measurement Error in Structural Equation Models: Implications for Theory Testing. Mark. Sci. 2004, 23, 519–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorsuch, R.L. Exploratory Factor Analysis: Its Role in Item Analysis. J. Pers. Assess. 1997, 68, 532–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forza, C.; Filippini, R. TQM impact on quality conformance and customer satisfaction: A causal model. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 1998, 55, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanders, S.R. North Versus South: The effects of foreign direct investment and historical legacies on poverty reduction in post-Đổi Mới Vietnam. J. Vietnam. Stud. 2014, 9, 46–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Paths | λ | Cronbach’s α | AVE | CR | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| VZV | VZK | VZV | VZK | VZV | VZK | VZV | VZK | |

| CGCoI → CGCoI 1 | 0.798 | 0.713 | 0.606 | 0.712 | 0.606 | 0.516 | 0.820 | 0.762 |

| CGCoI → CGCoI 2 | 0.855 | 0.706 | ||||||

| CGCoI → CGCoI 3 | 0.671 | 0.735 | ||||||

| AGCoI → AGCoI 1 | 0.713 | 0.744 | 0.680 | 0.641 | 0.510 | 0.511 | 0.757 | 0.758 |

| AGCoI → AGCoI 2 | 0.728 | 0.712 | ||||||

| AGCoI → AGCoI 3 | 0.702 | 0.687 | ||||||

| GT → GT 1 | 0.701 | 0.703 | 0.796 | 0.798 | 0.501 | 0.522 | 0.801 | 0.813 |

| GT → GT 2 | 0.735 | 0.777 | ||||||

| GT → GT 3 | 0.693 | 0.696 | ||||||

| GT → GT 4 | 0.704 | 0.712 | ||||||

| PI → PI 1 | 0.791 | 0.704 | 0.901 | 0.865 | 0.696 | 0.664 | 0.901 | 0.887 |

| PI → PI 2 | 0.898 | 0.867 | ||||||

| PI → PI 3 | 0.802 | 0.855 | ||||||

| PI → PI 4 | 0.842 | 0.822 | ||||||

| CGCoI | AGCoI | GT | PI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| VZV (N = 221) | 4.84 (1.44) | 4.53 (1.44) | 4.78 (1.22) | 3.45 (1.75) |

| VZK (N = 219) | 5.26 (2.19) | 4.82 (1.17) | 5.04 (1.31) | 5.06 (1.20) |

| Total (N = 440) | 5.05 (1.86) | 4.68 (1.32) | 4.91 (1.27) | 4.25 (1.70) |

| F | 4.661 * | 5.261 * | 4.219 * | 126.553 *** |

| Variables | CGCoI | AGCoI | GT | PI | CGCoI | AGCoI | GT | PI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| VZV (N = 221) | VZK (N = 219) | |||||||

| CGCoI | 1 | 1 | ||||||

| AGCoI | 0.55 ** | 1 | 0.53 ** | 1 | ||||

| GT | 0.49 ** | 0.52 ** | 1 | 0.46 ** | 0.51 ** | 1 | ||

| PI | 0.12 | 0.06 | 0.09 | 1 | 0.23 ** | 0.19 ** | 0.09 | 1 |

| VZV | VZK | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Path | ꞵ | t | p-value | Result | ꞵ | t | p-value | Result |

| CGCoI → PI | 0.264 | 1.740 * | 0.042 | Supported | 0.627 | 2.484 * | 0.013 | Supported |

| AGCoI → PI | 0.301 | 0.951 | 0.341 | Rejected | 0.900 | 2.617 ** | 0.009 | Supported |

| CGCoI → GT | 0.129 | 1.316 | 0.188 | Rejected | 0.257 | 1.749 | 0.080 | Rejected |

| AGCoI → GT | 0.679 | 3.772 *** | 0.000 | Supported | 0.565 | 2.993 ** | 0.003 | Supported |

| GT → PI | 0.198 | 0.989 | 0.323 | Rejected | 0.272 | 1.465 | 0.143 | Rejected |

| Model Fit | χ2 (df) = 166.122 (71) *** GFI = 0.907 AGFI = 0.863 NFI = 0.887 RMR = 0.139 RMSEA = 0.078 | χ2 (df) = 189.634 (71) *** GFI = 0.897 AGFI = 0.847 NFI = 0.857 RMR = 0.187 RMSEA = 0.088 | ||||||

| Model | df | CMIN (χ2) | CFI | RMSEA | Δχ2 (Δdf) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unconstrained model | 142 | 392.169 | 0.896 | 0.063 | ||

| Measurement weights | 152 | 432.451 | 0.883 | 0.065 | 40.282 (10) | 0.097 |

| Path | χ2 Differences between Parameters | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| df | CMIN | p-Value | NFI | IFI | RFI | TLI | |

| H1. CGCoI → PI | 1 | 12.239 *** | 0.000 | 0.005 | 0.005 | 0.005 | 0.006 |

| H2. AGCoI → PI | 1 | 1.185 | 0.276 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.001 | 0.001 |

| H3. CGCoI → GT | 1 | 3.552 | 0.059 | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.000 | 0.000 |

| H4. AGCoI → GT | 1 | 21.759 *** | 0.000 | 0.008 | 0.009 | 0.011 | 0.012 |

| H5. GT → PI | 1 | 11.283 ** | 0.001 | 0.004 | 0.005 | 0.005 | 0.005 |

© 2020 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lee, Y.-K. The Relationship between Green Country Image, Green Trust, and Purchase Intention of Korean Products: Focusing on Vietnamese Gen Z Consumers. Sustainability 2020, 12, 5098. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12125098

Lee Y-K. The Relationship between Green Country Image, Green Trust, and Purchase Intention of Korean Products: Focusing on Vietnamese Gen Z Consumers. Sustainability. 2020; 12(12):5098. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12125098

Chicago/Turabian StyleLee, You-Kyung. 2020. "The Relationship between Green Country Image, Green Trust, and Purchase Intention of Korean Products: Focusing on Vietnamese Gen Z Consumers" Sustainability 12, no. 12: 5098. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12125098

APA StyleLee, Y.-K. (2020). The Relationship between Green Country Image, Green Trust, and Purchase Intention of Korean Products: Focusing on Vietnamese Gen Z Consumers. Sustainability, 12(12), 5098. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12125098