Modeling Physical Activity, Mental Health, and Prosocial Behavior in School-Aged Children: A Gender Perspective

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Physical Activity (PA) and Mental Health (MH)

1.2. This Study

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sample

2.2. Data Collection Instruments

2.2.1. Physical Activity Self-Report, APALQ [19]

2.2.2. Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ) [18]

2.3. Procedure

2.4. Data Analysis

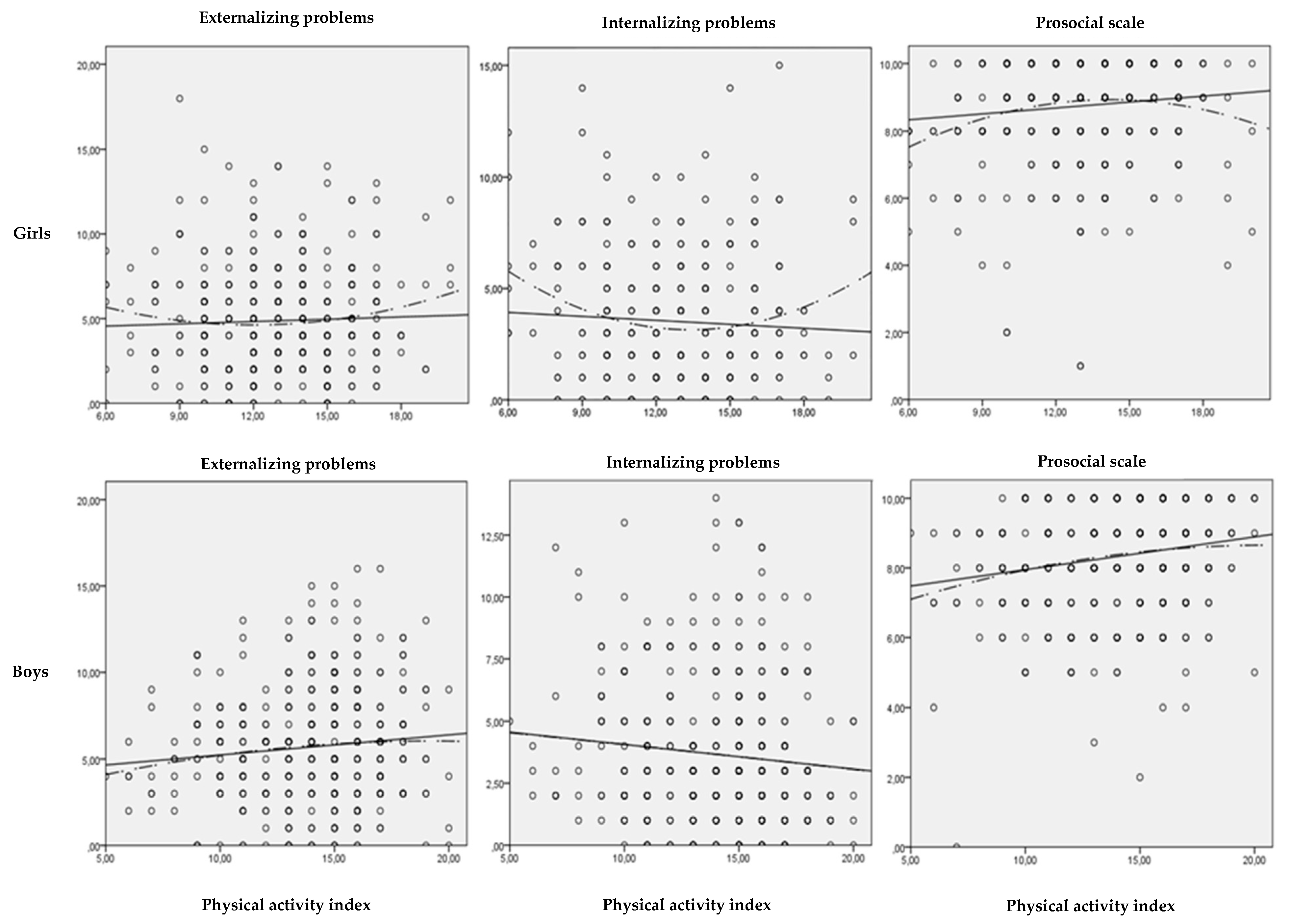

3. Results

4. Discussion

Study Limitations and Future Directions

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Reiner, M.; Niermann, C.; Jekauc, D.; Woll, A. Long-term health benefits of physical activity—A systematic review of longitudinal studies. BMC Public Health 2013, 13, 813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, I.M.; Shiroma, E.J.; Lobelo, F.; Puska, P.; Blair, S.N.; Katzmarzyk, P.T. Lancet Physical Activity Series Working Group. Effect of physical inactivity on major non-communicable diseases worldwide: An analysis of burden of disease and life expectancy. The Lancet 2012, 380, 219–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chekroud, S.R.; Gueorguieva, R.; Zheutlin, A.B.; Paulus, M.; Krumholz, H.M.; Krystal, J.H.; Chekroud, A.M. Association between physical exercise and mental health in 12 million individuals in the USA between 2011 and 2015: A cross-sectional study. Lancet Psychiatry 2018, 5, 739–746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beauchamp, M.R.; Puterman, E.; Lubans, D.R. Physical inactivity and mental health in late adolescence. JAMA Psychiatry 2018, 75, 543–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodriguez-Ayllon, M. Physical Activity, Sedentary Behaviour and Mental Health in Young People: A Review of Reviews. In Adolescent Health and Wellbeing; Pingitore, A., Mastorci, F., Vassalle, C., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; pp. 35–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biddle, S.J.; Ciaccioni, S.; Thomas, G.; Vergeer, I. Physical activity and mental health in children and adolescents: An updated review of reviews and an analysis of causality. Psychol. Sport Exerc. 2019, 42, 146–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dale, L.P.; Vanderloo, L.; Moore, S.; Faulkner, G. Physical activity and depression, anxiety, and self-esteem in children and youth: An umbrella systematic review. Mental Health Phys. Act. 2019, 16, 66–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richards, J.; Jiang, X.; Kelly, P.; Chau, J.; Bauman, A.; Ding, D. Don’t worry, be happy: Cross-sectional associations between physical activity and happiness in 15 European countries. BMC Public Health 2015, 15, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halliday, A.J.; Kern, M.L.; Turnbull, D.A. Can physical activity help explain the gender gap in adolescent mental health? A cross-sectional exploration. Mental Health Phys. Act. 2019, 16, 8–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guthold, R.; Stevens, G.A.; Riley, L.M.; Bull, F.C. Worldwide trends in insufficient physical activity from 2001 to 2016: A pooled analysis of 358 population-based surveys with 1·9 million participants. Lancet Glob. Health 2018, 6, e1077–e1086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kovess-Masfety, V.; Husky, M.M.; Keyes, K.; Hamilton, A.; Pez, O.; Bitfoi, A.; Carta, M.G.; Goelitz, D.; Kuijpers, R.; Otten, R.; et al. Comparing the prevalence of mental health problems in children 6–11 across Europe. Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 2016, 51, 1093–1103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- León, B.; Fajardo, F.; Mendo, S.; Rasskin, I.; Iglesias, D. Impact of the Familiar Environment in 11–14-Year-Old Minors’ Mental Health. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 2018, 15, 1314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ortuño, J.; Chocarro, E.; Fonseca, E.; Riba, S.S.; Muñiz, J. The assessment of emotional and Behavioural problems: Internal structure of The Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire. Int. J. Clin. Heal. Psychol. 2015, 15, 265–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Woerner, W.; Becker, A.; Rothenberger, A. Normative data and scale properties of the German parent SDQ. Eur. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2004, 13, ii3–ii10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yao, S.; Zhang, C.; Zhu, X.; Jing, X.; McWhinnie, C.M.; Abela, J.R.Z. Measuring adolescent psychopathology: Psychometric properties of the self-report strengths and difficulties questionnaire in a sample of Chinese adolescents. J. Adolesc. Health 2009, 45, 55–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fajardo-Bullón, F.; León, B.; Felipe-Castaño, E.; Santos, E.J. Mental health in the age group 4–15 years based on the results of the national survey of health 2006. Revista Española de Salud Pública 2012, 86, 445–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajmil, L.; Palacio-Vieira, J.A.; Herdman, M.; López-Aguilà, S.; Villalonga-Olives, E.; Valderas, J.M.; Espallargues, M.; Alonso, J. Effect on Health-related Quality of Life of changes in mental health in children and adolescents. Health Qual. Life Outcomes 2009, 7, 103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fonseca, E.; Paino, M.; Lemos, S.; Muñiz, J. Prevalencia de la sintomatología emocional y comportamental en adolescentes españoles a través del Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ). Rev. Psicop. y Ps. Clín. 2011, 16, 15–25. [Google Scholar]

- Zaragoza, J.; Generelo, E.; Aznar, S.; Abarca-Sos, A.; Julián, J.A.; Mota, J. Validation of a short physical activity recall questionnaire completed by Spanish adolescents. Eur. J. Sport Sci. 2012, 12, 283–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ledent, M.; Cloes, M.; Piéron, M. Les jeunes, leur activité physique et leurs perceptions de la santé, de la forme, des capacités athlétiques et de l’apparence. Sport 1997, 159, 90–95. [Google Scholar]

- Abarca-Sos, A.; Bois, J.; Zaragoza, J.; Generelo, E.; Julián, J.A. Ecological correlates of physical activity in youth: Importance of parents, friends, physical education teachers and geographical localization. Intern. J. Sport Psychol. 2013, 44, 215–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muris, P.; Meesters, C.; van den Berg, F. The Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ). Eur. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2003, 12, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gomez, R. Correlated Trait–Correlated Method Minus One Analysis of the Convergent and Discriminant Validities of the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire. Assessment 2014, 21, 372–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ortuño-Sierra, J.; Fonseca-Pedrero, E.; Paíno, M.; Aritio-Solana, R. Prevalence of emotional and behavioral symptomatology in Spanish adolescents. Rev. Psiquiatr. Salud Ment 2014, 7, 121–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goodman, A.; Lamping, D.L.; Ploubidis, G.B. When to use broader internalising and externalising subscales instead of the hypothesised five subscales on the strengths and difficulties questionnaire (SDQ): Data from British parents, teachers and children. J. Abnorm. Child Psychol. 2010, 38, 1179–1191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodman, A.; Goodman, R. Population mean scores predict child mental disorder rates: Validating SDQ prevalence estimators in Britain. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry Allied Discip. 2011, 52, 100–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodman, R. The strengths and difficulties questionnaire: A research note. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry Allied Discip. 1997, 38, 581–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Girls | Boys | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | M | SD | M | SD | t | p |

| Physical activity index | 12.92 | 2.74 | 13.94 | 2.88 | −5.172 | < 0.001 |

| Internalizing problems | 3.52 | 2.77 | 3.67 | 2.91 | −0.767 | 0.444 |

| Externalizing problems | 4.85 | 3.18 | 5.69 | 3.34 | −3.596 | < 0.001 |

| Prosocial scale | 8.76 | 1.53 | 8.32 | 1.53 | 4.102 | < 0.001 |

| Variables | Physical Activity Index | Externalizing Problems | Internalizing Problems | Prosocial Scale |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Physical activity index | 1 | 0.039 | −0.058 | 0.205 * |

| Externalizing problems | 0.201 * | 1 | 0.423 ** | −0.360 |

| Internalizing problems | −0.097 | 0.377 ** | 1 | 0.164 * |

| Prosocial scale | 0.278 ** | −0.271 | −0.164 | 1 |

| Dependent Variable | Equation | Girls | Boys | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Summary of the Model | Estimates of the Parameters | Summary of the Model | Estimates of the Parameters | ||||||||||

| R2 | F | P | Constant | b1 | b2 | R2 | F | P | Constant | b1 | b2 | ||

| Externalizing problems | Linear | 0.001 | 0.563 | 0.454 | 4.287 | 0.045 | 0.010 | 4.105 | 0.043 | 4.074 | 0.116 | ||

| Quadratic | 0.010 | 1.865 | 0.156 | 8.819 | −0.699 | 0.029 | 0.011 | 2.243 | 0.108 | 2.490 | 0.370 | −0.010 | |

| Internalizing problems | Linear | 0.003 | 1.239 | 0.266 | 4.279 | −0.059 | 0.009 | 3.955 | 0.048 | 5.053 | −0.099 | ||

| Quadratic | 0.033 | 6.151 | 0.002 | 11.753 | −1.285 | 0.048 | 0.009 | 1.873 | 0.155 | 4.988 | −0.089 | 0 | |

| Prosocial scale | Linear | 0.011 | 4.329 | 0.038 | 7.984 | 0.059 | 0.032 | 13.748 | 0 | 7.008 | 0.094 | ||

| Quadratic | 0.030 | 5.927 | 0.003 | 4.708 | 0.594 | −0.021 | 0.034 | 7.328 | 0.001 | 5.937 | 0.265 | −0.006 | |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Iglesias Gallego, D.; León-del-Barco, B.; Mendo-Lázaro, S.; Leyton-Román, M.; González-Bernal, J.J. Modeling Physical Activity, Mental Health, and Prosocial Behavior in School-Aged Children: A Gender Perspective. Sustainability 2020, 12, 4646. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12114646

Iglesias Gallego D, León-del-Barco B, Mendo-Lázaro S, Leyton-Román M, González-Bernal JJ. Modeling Physical Activity, Mental Health, and Prosocial Behavior in School-Aged Children: A Gender Perspective. Sustainability. 2020; 12(11):4646. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12114646

Chicago/Turabian StyleIglesias Gallego, Damián, Benito León-del-Barco, Santiago Mendo-Lázaro, Marta Leyton-Román, and Jerónimo J. González-Bernal. 2020. "Modeling Physical Activity, Mental Health, and Prosocial Behavior in School-Aged Children: A Gender Perspective" Sustainability 12, no. 11: 4646. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12114646

APA StyleIglesias Gallego, D., León-del-Barco, B., Mendo-Lázaro, S., Leyton-Román, M., & González-Bernal, J. J. (2020). Modeling Physical Activity, Mental Health, and Prosocial Behavior in School-Aged Children: A Gender Perspective. Sustainability, 12(11), 4646. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12114646