Implementing a Teacher-Focused Intervention in Physical Education to Increase Pupils’ Motivation towards Dance at School

Abstract

1. Introduction

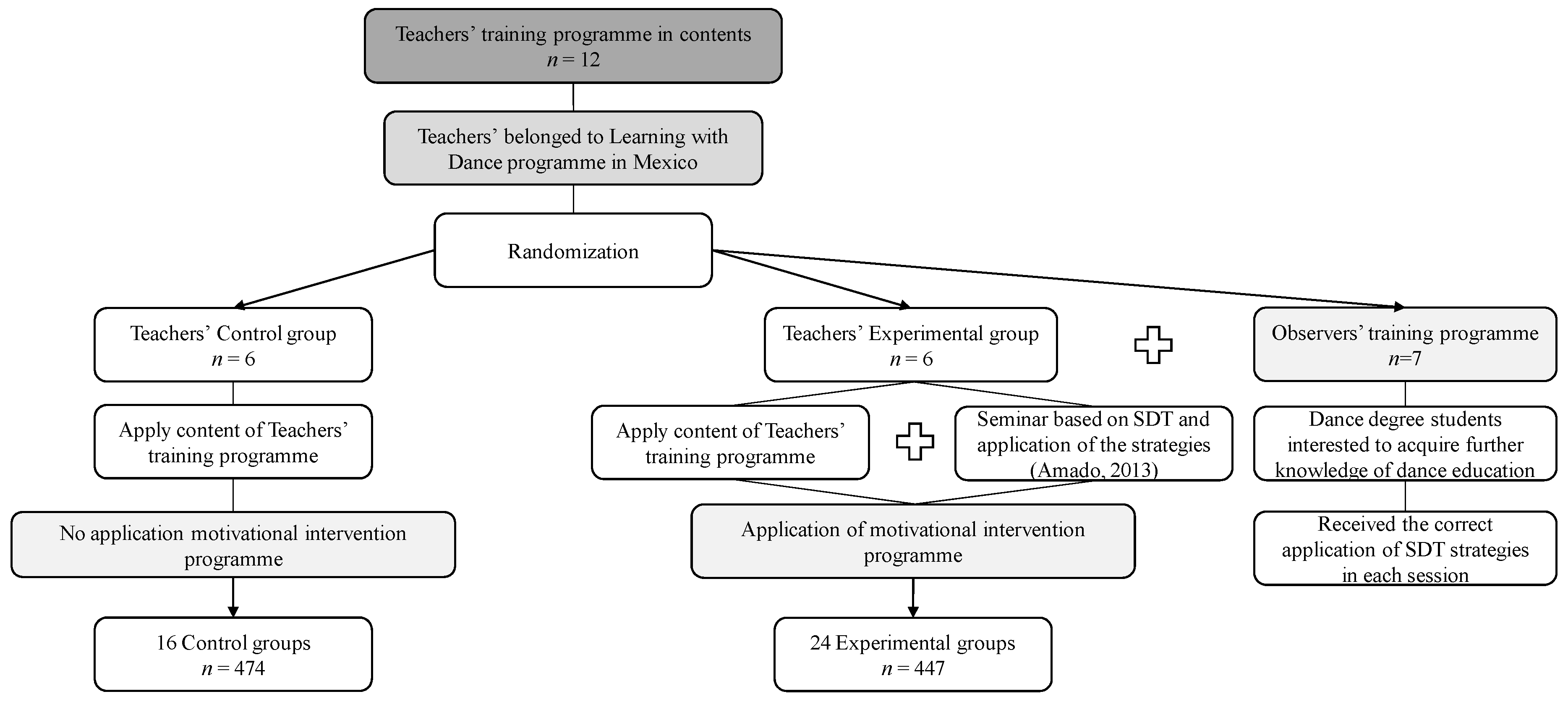

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Instruments

2.3. Procedure

2.4. Data Collect

2.5. Fidelity Procedure

2.6. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive Statistics and Reliability Analysis

3.2. Preliminary Analysis of the Groups before Development of the Intervention Program

3.3. Comparison of Groups Based on the Effects of the Motivational Intervention Program

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

6. Contribution to the Scientific Community

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Pate, R.R.; O’Neill, J.R. After-school interventions to increase physical activity among youth. Br. J. Sports Med. 2009, 43, 14–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sebire, S.J.; Mcneill, J.; Pool, L.; Haase, A.M.; Powell, J.; Jago, R. Designing extra-curricular dance programs: UK physical education and dance teachers’ perspectives. Open J. Prev. Med. 2013, 3, 111–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, B.S.C.; Wang, C.K.J. Perceived autonomy support, behavioural regulations in physical education and physical activity intention. Psychol. Sport Exerc. 2009, 10, 52–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gillet, N.; Vallerand, R.J.; Lafrenière, M.A.K. Intrinsic and extrinsic school motivation as a function of age: The mediating role of autonomy support. Soc. Psychol. Educ. 2012, 15, 77–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, H.; Reeve, J.; Deci, E.L. Engaging students in learning activities: It is not autonomy support or structure, but autonomy support and structure. J. Educ. Psychol. 2010, 102, 588–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirby, S.; Byra, M.; Readdy, T.; Wallhead, T. Effects of Spectrum Teaching Styles on College Students’ Psychological Needs Satisfaction and Self-Determined Motivation. Eur. Phys. Educ. Rev. 2015, 21, 521–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guay, F.; Chanal, J.; Ratelle, C.F.; Marsh, H.; Larose, S.; Boivin, M. Intrinsic, identified, and controlled types of motivation for school subjects in young elementary school children. Br. J. Educ. Psychol. 2010, 80, 711–735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McPherson, G.E.; O’Neill, S.A. Students’ motivation to study music as compared to other school subjects: A comparison of eight countries. Res. Stud. Music Educ. 2010, 32, 101–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torrents, C.T.; Serra, M.M.; Anzano, A.P.; Dinusôva, M. The possibilities of expressive movement and creative dance tasks to provoke emotional responses. Rev. Psicol. Deport. 2011, 20, 401–412. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, Z.; Hannan, P.; Xiang, P.; Stodden, D.F.; Valdez, V.E. Video game-based exercise, Latino children’s physical health, and academic achievement. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2013, 44, S240–S246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassandra, M.; Goudas, M.; Chroni, S. Examining factors associated with intrinsic motivation in physical education: A qualitative approach. Psychol. Sport Exerc. 2003, 4, 211–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lonsdale, C.; Sabiston, C.M.; Raedeke, T.D.; Ha, A.S.C.; Sum, R.K.W. Self-determined motivation and students’ physical activity during structured physical education lessons and free choice periods. Prev. Med. 2009, 48, 69–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ryan, R.M.; Deci, E.L. Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and well-being. Am. Psychol. 2000, 55, 68–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deci, E.L.; Ryan, R.M. The “What” and “Why” of Goal Pursuits: Human Needs and the Self-Determination of Behavior. Psychol. Inq. 2000, 11, 227–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deci, E.L.; Ryan, R.M. Intrinsic Motivation and Self-Determination in Human Behavior; Plenum Publishing Co: New York, NY, USA, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Rutten, C.; Boen, F.; Seghers, J. How school social and physical environments relate to autonomous motivation in physical education: The mediating role of need satisfaction. J. Teach. Phys. Educ. 2012, 31, 216–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Solmon, M.A.; Kosma, M.; Carson, R.L.; Gu, X. Need support, need satisfaction, intrinsic motivation, and physical activity participation among middle school students self-determination theory. J. Teach. Phys. Educ. 2011, 30, 51–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cox, A.E.; Ullrich-French, S.; Madonia, J.; Witty, K. Social physique anxiety in physical education: Social contextual factors and links to motivation and behavior. Psychol. Sport Exerc. 2011, 12, 555–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, I.M.; Ntoumanis, N.; Standage, M.; Spray, C.M. Motivational predictors of physical education students’ effort, exercise intentions, and leisure-time physical activity: A multilevel linear growth analysis. J. Sport Exerc. Psychol. 2010, 32, 99–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Timo, J.; Sami, Y.P.; Anthony, W.; Jarmo, L. Perceived physical competence towards physical activity, and motivation and enjoyment in physical education as longitudinal predictors of adolescents’ self-reported physical activity. J. Sci. Med. Sport 2016, 19, 750–754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDavid, L.; Cox, A.E.; McDonough, M.H. Need fulfillment and motivation in physical education predict trajectories of change in leisure-time physical activity in early adolescence. Psychol. Sport Exerc. 2014, 15, 471–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lander, N.; Eather, N.; Morgan, P.J.; Salmon, J.; Barnett, L.M. Characteristics of Teacher Training in School-Based Physical Education Interventions to Improve Fundamental Movement Skills and/or Physical Activity: A Systematic Review. Sports Med. 2017, 47, 135–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nurmi, J.; Hagger, M.S.; Haukkala, A.; Araújo-Soares, V.; Hankonen, N. Relations Between Autonomous Motivation and Leisure-Time Physical Activity Participation: The Mediating Role of Self-Regulation Techniques. J. Sport Exerc. Psychol. 2016, 38, 128–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adie, J.W.; Duda, J.L.; Ntoumanis, N. Autonomy support, basic need satisfaction and the optimal functioning of adult male and female sport participants: A test of basic needs theory. Motiv. Emot. 2008, 32, 189–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Oliva, D.; Sánchez-Miguel, P.A.; Kinnafick, F.-E.; Leo, F.M.; García-Calvo, T. Physical education lessons and physical activity intentions within Spanish Secondary Schools: A Self-Determination perspective. J. Teach. Phys. Educ. 2014, 33, 232–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, H.; Reeve, J.; Ryan, R.M.; Kim, A. Can Self-Determination Theory Explain What Underlies the Productive, Satisfying Learning Experiences of Collectivistically Oriented Korean Students? J. Educ. Psychol. 2009, 101, 644–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hodge, K.; Lonsdale, C.; Ng, J.Y.Y. Burnout in elite rugby: Relationships with basic psychological needs fulfilment. J. Sports Sci. 2008, 26, 835–844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vallerand, R.J. A hierarchical model of intrinsic and extrinsic motivation for sport and physical activity. Adv. Motiv. Sport Exerc. 2001, 2, 263–319. [Google Scholar]

- Chang, Y.K.; Chen, S.; Tu, K.W.; Chi, L.K. Effect of autonomy support on self-determined motivation in elementary physical education. J. Sport. Sci. Med. 2016, 15, 460–466. [Google Scholar]

- Cheon, S.H.; Reeve, J. Do the benefits from autonomy-supportive PE teacher training programs endure?: A one-year follow-up investigation. Psychol. Sport Exerc. 2013, 14, 508–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hastie, P.A.; Rudisill, M.E.; Wadsworth, D.D. Providing students with voice and choice: Lessons from intervention research on autonomy-supportive climates in physical education. Sport Educ. Soc. 2013, 18, 38–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ntoumanis, N. study of participation in optional school physical education using a self-determination theory framework. J. Educ. Psychol. 2005, 97, 444–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, B.; McCaughtry, N.; Martin, J.; Fahlman, M. Effects of Teacher Autonomy Support and Students’ Autonomous Motivation on Learning in Physical Education. Res. Q. Exerc. Sport 2009, 80, 44–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tessier, D.; Sarrazin, P.; Ntoumanis, N. The effect of an intervention to improve newly qualified teachers’ interpersonal style, students motivation and psychological need satisfaction in sport-based physical education. Contemp. Educ. Psychol. 2010, 35, 242–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, Y.L.; Reeve, J. A Meta-analysis of the Effectiveness of Intervention Programs Designed to Support Autonomy. Educ. Psychol. Rev. 2011, 23, 159–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skinner, E.A.; Belmont, M.J. Motivation in the classroom: Reciprocal effects of teacher behavior and student engagement across the school year. J. Educ. Psychol. 1993, 85, 571–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deci, E.L.; Ryan, R.M. The Support of Autonomy and the Control of Behavior. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1987, 53, 1024–1037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deci, E.L.; Eghrari, H.; Patrick, B.C.; Leone, D.R. Facilitating internalization: The self-determination theory perspective. J. Pers. 1994, 62, 119–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skinner, E.; Edge, K. Self-determination, coping, and development. In Handbook of Self-Determination Research; Deci, E.L., Ryan, R.M., Eds.; University of Rochester Press: New York, NY, USA, 2002; pp. 297–337. [Google Scholar]

- Deci, E.L.; Ryan, R.M. A motivational approach to self: Integration in personality. Neb. Symp. Motiv. 1990, 38, 237–288. [Google Scholar]

- Vlachopoulos, S.P.; Michailidou, S. Development and initial validation of a measure of autonomy, competence, and relatedness: The Basic Psychological Needs in Exercise Scale. Meas. Phys. Educ. Exerc. Sci. 2006, 10, 179–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno, J.A.; Gonzalez-Cutre, D.; Chillón, M.; Parra, N. Adaptation to Physical Education of the Basic Psychological Needs Scale in Exercise. Rev. Mex. Psicol. 2008, 25, 295–303. [Google Scholar]

- Amado, D.; Leo, F.M.; Sánchez-Oliva, D.; González-Ponce, I.; Chamorro, J.L.; Pulido, J.J. Analysis of the Psychometries properties of the Motivation in Dance and Corporal Expression Questionnaire. Abstr. II Natl. Congr. Dance Investig. 2012, 10, 16–18. [Google Scholar]

- Alonso, D.A. La Danza Entendida Desde Una Perspectiva Psicológica; Wanceulen: Sevilla, Spain, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, J. A coefficient of agreement for nominal scales. Educ. Psychol. Meas. 1960, 20, 37–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fleiss, J.L. Measuring nominal scale agreement among many raters. Psychol. Bull. 1971, 76, 378–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haerens, L.; Aelterman, N.; Vansteenkiste, M.; Soenens, B.; Van Petegem, S. Do perceived autonomy-supportive and controlling teaching relate to physical education students’ motivational experiences through unique pathways? Distinguishing between the bright and dark side of motivation. Psychol. Sport Exerc. 2015, 16, 26–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amado, D.; Del Villar, F.; Leo, F.M.; Sánchez-Oliva, D.; Sánchez-Miguel, P.A.; García-Calvo, T. Effect of a multi-dimensional intervention programme on the motivation of physical education students. PLoS ONE 2014, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lobo, Y.B.; Winsler, A. The effects of a creative dance and movement program on the social competence of head start preschoolers. Soc. Dev. 2006, 15, 501–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mainwaring, L.M.; Krasnow, D.H. Teaching the dance class: Strategies to enhance skill acquisition, mastery, and positive self-image. J. Danc. Educ. 2010, 10, 14–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mancini, K. Dancing through the school day: How dance catapults learning in elementary education. J. Phys. Educ. Recreat. Danc. 2013, 84, 6–8. [Google Scholar]

- Ntoumanis, N.; Barkoukis, V.; Thøgersen-Ntoumani, C. Developmental Trajectories of Motivation in Physical Education: Course, Demographic Differences, and Antecedents. J. Educ. Psychol. 2009, 101, 717–728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatzisarantis, N.L.D.; Hagger, M.S. Effects of an intervention based on self-determination theory on self-reported leisure-time physical activity participation. Psychol. Health 2009, 24, 29–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edmunds, J.; Ntoumanis, N.; Duda, J.L. Testing a self-determination theory-based teaching style intervention in the exercise domain. Eur. J. Soc. Psychol. 2008, 38, 375–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Standage, M.; Duda, J.L.; Ntoumanis, N. A test of self-determination theory in school physical education. Br. J. Educ. Psychol. 2005, 75, 411–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taylor, I.M.; Ntoumanis, N. Teacher motivational strategies and student self-determination in physical education. J. Educ. Psychol. 2007, 99, 747–760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ntoumanis, N. A self-determination approach to the understanding of motivation in physical education. Br. J. Educ. Psychol. 2001, 71, 225–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Contents | |

|---|---|

| Theme 1 | Dance and corporal expression at the school |

| Concept of educational dance | |

| The style technique | |

| The creative technique | |

| Movement factors | |

| Ways of corporal expression | |

| The literacy process of body language | |

| Theme 2 | Body |

| Theme 3 | Weight |

| Theme 4 | Contact |

| Theme 5 | Space |

| Theme 6 | Time |

| Theme 7 | Intensity |

| Theme 8 | Interaction |

| Theme 9 | Methods for learning to create |

| Theme 10 | The construction of the observatory’s sight |

| Theme 11 | Didactics of the physical-artistic activities |

| 11.1 Selection of proposals | |

| 11.2 The group dynamic, the constructivist reflection and the evaluation | |

| WEEK 1 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hour | Monday | Tuesday | Wednesday | Thursday | Friday |

| 09:00–11:00 | Content 1 | Content 3 | Content 5 | Content 7 | Review of Contents |

| 11:00–11:30 | Break | Break | Break | Break | Break |

| 11:30–14:30 | Content 2 | Content 4 | Content 6 | Content 8 | Review of Contents |

| WEEK 2 | |||||

| Hour | Monday | Tuesday | Wednesday | Thursday | Friday |

| 09:00–11:00 | Content 9 | Content 11 | Strategy Training | Strategy Training | Strategy Training |

| 11:00–11:30 | Break | Break | Break | Break | Break |

| 11:30–14:30 | Content 10 | Review of Contents | Strategy Training | Strategy Training | Strategy Training |

| 16:30–20:30 | Observer Training | Observer Training | Observer Training | ||

| PRE | POST | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| VARIABLES | M | SD | α | Skewness | Kurtosis | M | SD | α | Skewness | Kurtosis |

| BPN satisfaction | ||||||||||

| Competence | 3.79 | 0.84 | 0.71 | −0.69 | 0.26 | 3.50 | 0.91 | 0.74 | −0.48 | −0.09 |

| Autonomy | 3.52 | 0.96 | 0.77 | −0.52 | −0.32 | 3.33 | 0.99 | 0.77 | −0.31 | −0.48 |

| Relatedness | 3.82 | 0.92 | 0.76 | −0.69 | −0.12 | 3.48 | 0.98 | 0.77 | −0.36 | −0.48 |

| Type of motivation | ||||||||||

| Intrinsic | 3.90 | 0.93 | 0.80 | −0.89 | 0.30 | 3.60 | 0.99 | 0.80 | −0.58 | −0.20 |

| Identified | 3.87 | 0.88 | 0.76 | −0.73 | −0.03 | 3.51 | 0.99 | 0.82 | −0.49 | −0.24 |

| Introjected | 3.36 | 0.87 | 0.68 | −0.22 | −0.52 | 3.19 | 0.90 | 0.68 | −0.22 | −0.31 |

| External | 3.62 | 0.87 | 0.70 | −0.42 | −0.34 | 3.33 | 0.92 | 0.69 | −0.24 | −0.38 |

| Amotivation | 2.59 | 0.99 | 0.70 | 0.28 | −0.59 | 2.75 | 0.99 | 0.70 | 0.13 | −0.57 |

| Post-Test | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Experimental Group | Control Group | |||||

| Measure | M | SD | M | SD | F | η2 |

| BPN satisfaction | ||||||

| Competence | 3.54 | 0.87 | 3.46 | 0.96 | 2.21 | 0.00 |

| Autonomy | 3.40 | 0.99 | 3.25 | 0.99 | 6.95 ** | 0.01 |

| Relatedness | 3.53 | 0.98 | 3.42 | 0.98 | 6.51 ** | 0.01 |

| Type of motivation | ||||||

| Intrinsic motivation | 3.65 | 0.95 | 3.54 | 1.04 | 3.60 * | 0.00 |

| Identified regulation | 3.56 | 0.4 | 3.45 | 0.5 | 3.44 * | 0.00 |

| Introjected regulation | 3.22 | 0.88 | 3.17 | 0.92 | 0.73 | 0.00 |

| External regulation | 3.36 | 0.88 | 3.30 | 0.97 | 1.66 | 0.00 |

| Amotivation | 2.74 | 0.96 | 2.74 | 1.03 | 0.18 | 0.00 |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Amado, D.; Molero, P.; Del Villar, F.; Tapia-Serrano, M.Á.; Sánchez-Miguel, P.A. Implementing a Teacher-Focused Intervention in Physical Education to Increase Pupils’ Motivation towards Dance at School. Sustainability 2020, 12, 4550. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12114550

Amado D, Molero P, Del Villar F, Tapia-Serrano MÁ, Sánchez-Miguel PA. Implementing a Teacher-Focused Intervention in Physical Education to Increase Pupils’ Motivation towards Dance at School. Sustainability. 2020; 12(11):4550. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12114550

Chicago/Turabian StyleAmado, Diana, Pablo Molero, Fernando Del Villar, Miguel Ángel Tapia-Serrano, and Pedro Antonio Sánchez-Miguel. 2020. "Implementing a Teacher-Focused Intervention in Physical Education to Increase Pupils’ Motivation towards Dance at School" Sustainability 12, no. 11: 4550. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12114550

APA StyleAmado, D., Molero, P., Del Villar, F., Tapia-Serrano, M. Á., & Sánchez-Miguel, P. A. (2020). Implementing a Teacher-Focused Intervention in Physical Education to Increase Pupils’ Motivation towards Dance at School. Sustainability, 12(11), 4550. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12114550