Abstract

This paper aims to investigate the mediating role of work engagement for the effects of deep acting, perceived organizational support, and self-efficacy on service quality under the conservation of resources (COR) theory and the job demands–resources (JD-R) model. Questionnaires were rigorously distributed by stratified random sampling. Data were collected from hospitality frontline employees (HFLEs) of hotels and restaurants in Taiwan during a period of two months. Structural equation modeling analyses were conducted to assess the data. Empirical results demonstrated work engagement is a significant mediator, enriching the antecedents and consequences of work engagement in hospitality literature. The findings suggest hospitality practitioners should consider a high-performance work system (HPWS) as an employee management tactic to implement sustainable human resource management (HRM). This practice can augment hospitality frontline employees’ willingness to stay in organizations in the long term and to maintain a satisfying service quality.

1. Introduction

Hospitality frontline employees (HFLEs) are indispensable for a firm for their responsibility of delivering successful services in today’s competitive service industry [1]. Additionally, they are considered the key to customer’s service experience [2]. Accordingly, HFLEs are valuable for a service firm [3], and their well-being and strengths in the workplace are worth researching [4]. However, psychology has been ignoring mental wellness, the opposite of mental illness [5,6]. Besides, hospitality industry is regarded as one of the most stressful jobs [7]. To illustrate this, employees in the hospitality industry are exposed to burnout [8], anti-social work hours [9], and work-family conflicts [10]. Therefore, it is more important to focus on employee’s well-being than to train employees to perform service quality [11]. Furthermore, to have a long-term successful enterprise, it is indispensable to conduct sustainable human resource management (HRM) to attract and retain valuable employees. In other words, research in positive organizational behaviors, such as work engagement, is necessary [12].

Since employee participation is seen as one of the core characteristics of sustainable HRM [13], the main concern of this study was to understand how to inspire HFLEs to perform service quality, engaging them in their work. Hence, according to the conservation of resources (COR) theory [14,15] and the job demands–resources (JD-R) model [16,17], selected positive antecedents of work engagement were empirically examined and demonstrated a positive influence on service quality. This finding enriches the previous results on work engagement reported in a limited number of empirical studies. Furthermore, this study provides valid reasons for hospitality practitioners to reconsider the importance of positive psychology and develop a sustainable HRM in order to decrease HFLEs’ high turnover intentions. Finally, combining deep acting, perceived organizational support (POS), and self-efficacy with a high-performance work system (HPWS) in a consistent way and explaining the importance of service quality is beneficial to the sustainability of successful hospitality companies.

The purpose of this study was to probe the mediating role of work engagement for the effects of deep acting, POS, and self-efficacy in service quality using the COR theory as well as the JD-R model. First, deep acting was found to produce positive outcomes when an organization adopts a positive display rule that calls for the expression of positive emotions [18]. Secondly, how HFLEs behavior with customers will reflect the way they are treated by the organization [19]. Thirdly, HFLEs who strongly believe in their capabilities enjoy more their job and perform better [20,21]. Moreover, work engagement is seen as a critical mediator among HFLEs [22]. Finally, it was revealed the more HFLEs are engaged in their work, the better they perform [23].

2. Literature Review

2.1. Sustainable HRM

In the past decades, strategic HRM led organizations to short-term business success [24]. It focused more on financial performance than on other organizational outcomes, ignoring employee’s well-being [25]. Humanity has not been valued by the service industry until recently, when it has become apparent that it can promote unique and touching experiences. Hence, stimulating employees to bring their humanity into the working environment has become a contemporary practice [26]. For an organization, satisfying customers requires satisfying employees first. Strategic HRM was, therefore, expanded to sustainable HRM, which further develops people management. Namely, the sustainability of an organization mainly emphasizes profitability and human performances [27]. The hospitality industry particularly relies on a high level of interactions between customers and employees. Obtaining and retaining high-quality employees is, thus, a survival strategy for hospitality practitioners to reach a long-term successful business from the perspective of sustainability [24]. Several studies have integrated sustainable HRM into the workplace [28,29], yet few have examined sustainable HRM under a research framework, especially in the hospitality industry, to better comprehend its effects on human work performance.

2.2. Emotional Labor

Emotional labor is the process of adjusting feelings and expressions to organizational requirements [30]. Emotional labor can be commoditized as a service product, and, hence, it can be sold for a wage as an exchange value [31,32]. Besides, emotional labor is determined by the interactions between individuals and the social environment [31,32,33]. Since emotional expression is based on display rules established by an organization, it is relatively easy for customers, supervisors, and colleagues to observe whether an employee complies with the rules. Accordingly, emotional labor is an important job demand in the service industry and requires a certain degree of mental effort [32]. Even if an employee’s inner feeling is consistent with the display rules, this kind of mental effort is still needed, because the employee must convert the inner feeling into appropriate expressions.

The strategy of emotional labor is separated into two categories according to the degree of camouflage [31]. One is surface acting, which focuses on external emotional expression. The other is deep acting, focused on the expression of internal emotional feelings. Both of them are viewed as a way of managing emotions to adjust feelings and expressions [30]. Specifically, deep acting will happen first and, if it is not appreciated during an interaction, it will be followed by surface acting [34]. Likewise, surface acting occurs in response to a certain event, while deep acting happens continuously throughout the day [30]. Furthermore, emotional labor is classified as job-focused and employee-focused. The former includes interpersonal job requirements (frequency, duration, intensity, and diversity) and emotional controls (expressing hidden negative emotions and positive emotions), while the latter includes both surface acting and deep acting [35]. So far, the employee-focused approach has been the main one applied because it complies with Hochschild’s emotion management process [36,37,38].

2.3. Perceived Organizational Support (POS)

The concept of POS was proposed as a reversion of organizational commitment [39]. Employees usually pay more attention to organizational commitment toward them [40]. In other words, previous researches emphasized mainly contribution, recognition, and emotions of employees with respect to an organization, whereas POS reflects the support of an organization to employees. POS indicates the overall conviction of employees regarding their own contribution to an enterprise and whether the enterprise values their well-being. The higher the degree of conviction, the higher the efficiency and satisfaction of employees [41]. When employees perceive organizational supports, a reciprocity will be generated, influencing employees’ working attitude and working behavior [42]. Moreover, they will have a sense of obligation for an organization and work harder to achieve organizational goals [43]. Rhoades and Eisenberger [40] indicated that the more the firm values the contributions of employees and is concerned about their well-being, the higher the POS by the employees. Instead of trying to improve organizational commitment through old-fashioned methods such as promotions, wage increases, and benefits, organizations could concentrate more on policies and practices which increase POS among employees [44]. Therefore, it is essential to provide adequate organizational support that can motivate employees to offer high-quality performance in the workplace [45].

2.4. Self-Efficacy

Self-efficacy is the conviction that an individual has the ability to perform a specific task [46]. When accomplishing a particular goal, self-efficacy will determine the level of motivation, the degree of efforts, and how long an individual can persist in facing obstacles and aversive experiences [47]. Based on the social cognitive theory, both personal self-efficacy and environmental factors affect employee’s performance [48]. Accordingly, self-efficacy is a critical factor for the change of behavior and is considered a self-control mechanism, managing the motivation and actions of human beings [49]. Besides, an individual’s self-efficacy can prevent the negative effects of stress [50] and it influences personal work attitudes such as interests, goals, and behaviors in the working field [51]. However, most research about self-efficacy has been focused on the education domain over the last two decades [52,53,54,55]. Self-efficacy has not become a valued organizational variable until recently. Within an enterprise setting, self-efficacy plays a crucial role in job performance. For instance, it affects the levels of efforts and persistence of employees, especially when learning difficult tasks [56]. Likewise, self-efficacy significantly influences in a positive way frontline employees’ outcomes [57]. Despite few studies of self-efficacy on work performance in hospitality industry, some information can be obtained from recent empirical research. Self-efficacy enhances HFLEs’ performance and organizational commitment in hotels in Northern Cyprus [58]. To handle high-demand working conditions, self-efficacy is regarded as an indispensable trait for HFLEs [59]. Hence, it is important to encourage employees to have faith in their own abilities to perform the requested tasks and achieve success in their work [60]. Once they believe in themselves, they acquire high self-efficacy, related to a positive self-regulatory mechanism [47].

2.5. Work Engagement

The factors that influence work engagement and the effects of work engagement are both considered critical in an organization. Since academia realized the importance of positive psychology [61], it has become clear that also the hospitality field should consider it [62,63,64]. Building positive qualities rather than repairing negative things in life is a main concern of positive psychology [65]. Psychology research is thus developing the analysis of these positive aspects, and it is important to also understand the effects positive psychology in working environments [61]. One example of positive organizational behavior is work engagement, which is viewed as the opposite of burnout [12]. In contrast to a momentary and particular state, work engagement indicates a more consistent state and emotional cognition, which distinguish it from other work-related dimensions [66]. For instance, work engagement is distinct from job involvement and organizational commitment [67]. Work engagement is regarded as a mood or psychological state in which an individual is concentrated on performing work rather than on the organization [68]. It is found that engaged employees feel that time flies owing to their energetic and enthusiastic attitude [69]. Furthermore, they experience active and positive emotions and the integration of their job resources and personal resources [70].

2.6. Service Quality

The Nordic school [71,72] focuses on the outcomes of the interactions between customers and the firm, whereas the American school [73,74] emphasizes the methodology of service delivery. However, this results in overstating service quality’s cognitive aspects and ignoring its emotional features [75]. Accordingly, service quality was conceptualized on the basis of the complex customers’ lived experiences, moving beyond such static dimensions as responsiveness and reliability [76]. Furthermore, service quality was defined on the basis of consumption experiences involving various types of emotions and was considered the overall evaluation of a service provider [77]. Although service quality has been a popular research variable, the concept of service quality is still interpreted in multiple ways [78,79,80].

The service sector has dominated the hospitality economy in the past decades. Since service quality is regarded as the key element to affect business performance, how employees engage in their work has become a main issue, influencing an organization’s financial performance [81]. Objectively measuring the quality of service is harder than measuring the quality of products, owing to the well-known five dimensions of service quality [82]. Apart from the above distinguishing characteristics of service, particularly in hospitality industry, other attributes have further complicated the task of measuring service quality, such as fluctuating demand, information exchange, and peak periods [83,84]. As the saying goes, “Half a loaf is better than none”. With the growing number of competitors in hospitality industry, measuring service quality is still important for managers to adjust strategies leading their firm to success.

2.7. Integration of the COR Theory and the JD-R Model

Anything perceived by individuals to fulfill their targets is defined as a resource [85]. Since resource loss is faster than resource gain, it is necessary to invest in resources [15]. In addition, resources tend to produce other resources. Increasing resources generates more and more resources contributing to positive performances [86]. Accordingly, the COR theory states that individuals try to protect and accumulate resources. On the other hand, on the basis of the JD-R model, job resources lead to work engagement owing to their motivational potential [16]. Besides, job resources promote personal resources, which also result in work engagement [87]. The JD-R model is, therefore, expanded by demonstrating that job resources and personal resources are correlated. Moreover, both of them are viewed as the best premises of work engagement [88]. Finally, work engagement will benefit work-related outcomes in return. That is to say, employees who are engaged are able to create their own resources. Those resources will foster work engagement continuously and further enhance resources.

3. Conceptual Framework and Hypotheses Development

3.1. Relationship between Emotional Labor and Work Engagement

If the employees display their internal feelings in a workplace, deep acting can decrease the negative influence of emotional labor on work and health outcomes [89]. Authentic emotive expression positively related to work engagement among Chinese public servants [90]. In the limited hospitality literature, a meta-analysis reported that deep acting has positive outcomes when an organization adopts a positive display rule requiring the expression of positive emotions [18]. Hospitality and tourism frontline employees used to adopt a deep acting strategy when encountering emotional labor to protect them from emotional exhaustion [91].

Hypothesis 1 (H1).

HFLEs’ deep acting positively influences work engagement.

3.2. Relationship between Perceived Organizational Support and Work Engagement

A meta-analysis suggests that in organizations that support their employees, employees’ well-being is improved and employees manifest a beneficial orientation toward the organization [92]. HFLEs who feel supported by the organization they work for experience less turnover intentions and emotional exhaustion and display better customer service behaviors [93]. Similarly, when HFLEs perceive their organization helps resolve or alleviate complex conflicts with customers, their levels of engagement are significantly influenced [94]. Additionally, HFLEs will increase and improve the quality and quantity of their job when they perceive to be crucial and valued in a business firm [95].

Hypothesis 2 (H2).

HFLEs’ POS positively influences work engagement.

3.3. Relationship between Self-Efficacy and Work Engagement

HFLEs who strongly believe in their capabilities enjoy more their job and perform better in their current and future jobs [20,21]. That is to say, high self-efficacy, as a dimension of psychological capital, contributes to work engagement because personal resources will foster work engagement on the basis of the JD-R model [96,97]. Self-efficacy is more beneficial for engagement when employees encounter high levels of emotional demands [98]. In addition, self-efficacy fosters HFLEs’ psychological empowerment and work engagement [62].

Hypothesis 3 (H3).

HFLEs’ self-efficacy positively influences work engagement.

3.4. Relationship between Work Engagement and Service Quality

HFLEs play a vital role in hospitality customers’ service experience [2]. Engaged employees are willing to produce outcomes that will benefit the organization [99]. Furthermore, it was revealed in a study of 36 organizations in 8000 business sectors that the more HFLEs are engaged, the better they perform [23]. When within a setting of HFLEs, it is critical for supervisors to understand that work engagement plays a significant role in service quality and innovation [100]. The more highly HFLEs are engaged, the better their service quality [101]. In the same way, another recent research argues that engagement is related to HFLEs’ service delivery [102]. Nonetheless, according to the authors’ literature review, the effect of work engagement on service quality has not been addressed and, therefore, it is exciting to broaden the knowledge of work engagement.

Hypothesis 4 (H4).

HFLEs’ work engagement positively influences service quality.

3.5. Mediating Effects of Work Engagement

The abovementioned relationships imply work engagement mediates the effects of deep acting, POS, and self-efficacy on service quality. Recently, hospitality academia has focused on the mediating role of HFLEs’ work engagement and its impact on occupational performances such as innovative behavior [94], service recovery performance [103], and job satisfaction [96]. However, no empirical research was found investigating the mediating role of work engagement for the effects of deep acting, POS, and self-efficacy on service quality. Despite a lack of antecedents, we advance some hypotheses based on the following studies. First and foremost, emotional labor is positive not only for employees but also for customers [18]. In addition, HFLEs with positive affective displays can motivate a positive customer experience [104]. Second, work engagement mediates the relationship between POS and job performance [105]. Third, work engagement mediates the impact of self-efficacy on in-role and extra-role performance [106]. Finally, according to the COR theory and the JD-R model [16], positive resources appear to influence work engagement and will have positive impacts on job outcomes, leading to resource caravans [86]. Additionally, work engagement is considered a critical mediator among HFLEs [22]. The purpose of this study, therefore, was to investigate the mediating role of HFLEs’ work engagement for the effects of deep acting, POS, and self-efficacy on service quality.

Hypothesis 5a (H5a).

HFLEs’ work engagement mediates the effects of deep acting on service quality.

Hypothesis 5b (H5b).

HFLEs’ work engagement mediates the effects of POS on service quality.

Hypothesis 5c (H5c).

HFLEs’ work engagement mediates the effects of self-efficacy on service quality.

4. Methodology

4.1. Research Framework

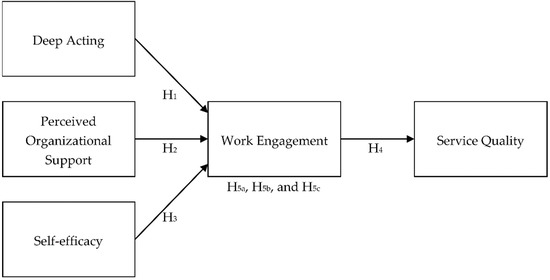

The COR theory and the JD-R model indicate that positive resources will influence the attitude of work engagement and will have positive impacts on job outcomes, leading to resources caravans. A research framework was, therefore, proposed to investigate whether work engagement mediates the effects of deep acting, POS, and self-efficacy on service quality considering the COR theory and the JD-R model (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Conceptual research framework.

4.2. Pilot Test

Duane and Consenza Robert [107] recommended to conduct a pilot test in a similar population before data collection to increase content validity. Accordingly, a pilot test was coordinated among 50 HFLMs, and the result showed a low Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin value of five reverse-coded items. However, if we delete them, the items of each construct will not be adequate to represent its validity. We altered the five reverse-coded items into forward ones, instead. For instance, “The organization shows very little concern for me” was revised to “The organization shows concern for me”.

4.3. Sampling Frame and Data Collection

Participants were frontline employees in three- to five-stars hotels and restaurants in Taiwan. Although some of them were foreign employees from Australia, Japan, Malaysia, and Thailand, the majority was Taiwanese. For those who completed the questionnaire, stainless steel straws and hand-made soaps were available as an appreciation gift and as an incentive to fulfill their jobs. Additionally, stratified random sampling and e-surveys were utilized in this study. Data collection was accomplished in a period of two months, for a rigorous sampling method requires sufficient time to distribute questionnaires and to communicate to each distinct unit. To ensure the sampling process could go continuously and simultaneously, the respondents were divided into two different groups. Nunnally [108] suggested the size of samples should be more than 10 times the number of the items. In this study, there were 34 items in sum, meaning a minimum size of 340 samples was needed. A total number of 536 questionnaires were collected before eliminating 16 invalid ones. Eventually, 520 questionnaires were analyzed, with group 1 containing 320 questionnaires and group 2 holding 200 questionnaires, resulting in an effective response rate of 97.01%. More specifically, the sample was composed of 63 firms, each firm had 1 to 5 departments, and each department contained 3 to 22 respondents.

4.4. Construct Measurement

This study adopted instruments which have been widely used to evaluate each of the constructs under study, so that content validity would ensure the accuracy of our particular assessment purpose [109]. A seven-point Likert Scale was used to score from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree). Firstly, to assess deep acting, this study adopted five items from the Hospitality Emotional Labor Scale [110], whose Cronbach’s alpha coefficient was measured as 0.82. Secondly, six items were adopted to measure POS from the Survey of Perceived Organizational Support [39], whose Cronbach’s alpha coefficient was measured as 0.70. Thirdly, four items were selected to evaluate self-efficacy from the scale of Schwarzer and Jerusalem [111], whose Cronbach’s alpha coefficient was measured as 0.80. Next, nine items were selected from the nine-item Utrecht Work Engagement Scale [112] to examine work engagement, whose Cronbach’s alpha coefficient was measured as 0.86. Lastly, participants were questioned about 10 items representing service quality with the scale of SERVQUAL [113], whose Cronbach’s alpha coefficient was measured as 0.82. Additionally, employee sex, age, work experience, and education level were included as control variables.

4.5. Analytic Approach

Since work engagement was thought of as the consequence of three selected positive resources and a crucial mediator, ANOVA was employed to investigate if it determines any significant difference between group 1 and group 2. Additionally, the two-step approach recommended by Anderson and Gerbing [114] was applied for structural equation modeling in this study. Data screening and preparation were assessed by AMOS 24.0 with maximum-likelihood estimation. In the first place, the evaluation of the measurement models was conducted through confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) to examine whether the existing measurement was appropriate for the current population [115]. In CFA, convergent validity test, discriminant validity test, and goodness-of-fit test were taken into consideration before path analysis. As for the goodness of fit of the model, it was evaluated by the overall chi-square (χ2) measure, the degrees of freedom by the chi-square (χ2/df), goodness of fit index (GFI), adjusted goodness of fit index (AGFI), standardized root mean square residual (SRMR), comparative fit index (CFI), and non-normed fit index (NNFI). Then, path analysis was illustrated to determine whether the data fit the model and to confirm the hypotheses of this study. Finally, Sobel test was utilized to analyze if the mediating effects of work engagement were significant [116].

5. Results

5.1. Demographic Statistics

Among the respondents (n = 520), 58.5% were female employees, and 41.5% were male. In terms of age, the majority were in their 20s (60.4%) and 30s (25.0%). Work experience was distributed across the following categories in descending order: 1 to 3 years (33.1%), 3 to 5 years (27.9%), below 1 year (22.1%), 5 to 7 years (10.6%), above 9 years (3.8%), and 7 to 9 years (2.5%). As for education level, 88.3% of the participants held a bachelor’s degree, and 10.0% owned a degree of senior high school. Please refer to Table 1.

Table 1.

Respondents’ profile.

5.2. ANOVA

Work engagement was tested by ANOVA in this study to assess whether group 1 and group 2 were distinct from each other. The total number of 520 participants was separated into group 1 with 320 participants and group 2 with 200 participants. As reported in Table 2, the average of group 1 was 4.32, and that of group 2 was 4.29. The variance of group 1 was 1.18, and that of group 2 was 0.58. Furthermore, the variation between group 1 and group 2 was rejected on the basis of the p-value (0.68) presented in Table 3. Namely, group 1 had no significant difference from group 2 in terms of the crucial mediator of work engagement.

Table 2.

Summary of ANOVA analysis of work engagement.

Table 3.

Results of ANOVA variation in work engagement.

5.3. Confirmatory Factor Analyses

Fornell and Larcker [117] suggested that to meet the satisfactory standard of convergent validity, two principles need to be accomplished. One is that construct reliability has to be higher than 0.60; the other is that each latent variable’s average variance extracted (AVE) has to be higher 0.25 [118]. In this study, construct reliability came with a good result ranging from 0.71 to 0.85. Additionally, AVE also performed well, with a score from 0.39 to 0.42. In sum, the proposed model possessed convergent validity. On the other hand, to ensure discriminant validity, the square root AVE of each construct has to be higher than the correlation value of each construct and, in overall comparison, the total number of qualified values have to account for more than 75% [118]. As shown in Table 4, the total number of correlation values among constructs in this study was 10, and that of qualified ones, lower than the square root of AVE, was 8. Apparently, the total number of qualified values accounted for 80%, resulting in good discriminant validity.

Table 4.

Correlation coefficients and square roots of average variance extracted (AVE).

As shown in Table 5, the constructs were evaluated by the degrees of freedom by the chi-square (χ2/df), which did not reach the criteria, except for POS scoring χ2/df = 2.30. For the domain of absolute fit indices, in terms of GFI, the constructs received satisfactory results with GFI scores from 0.93 to 1.00. As for AGFI, the constructs performed well, with AGFI scores from 0.87 to 0.98. Most of the constructs satisfied the recommended index of SRMR, lower than 0.08, except the service quality, scoring SRMR = 0.09. For the domain of incremental index, in terms of CFI, the constructs achieved convincing consequences, with CFI scores from 0.94 to 1.00. As for NNFI, it also indicated satisfying results, with the scores from 0.90 to 0.99. In short, most of the goodness of fit of the model indices tended to have good outcomes, indicating the proposed model passed the goodness of model fit. Finally, convergent validity test, discriminant validity test, and goodness-of-fit test were performed via confirmatory factor analysis. The proposed model showed acceptable internal and external qualities, suitable for path analysis.

Table 5.

Summary of goodness of model fit test.

5.4. Path Analysis

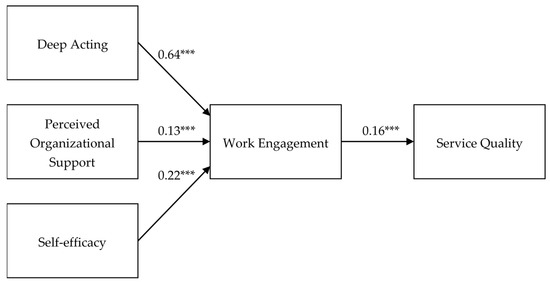

Figure 2 indicates that deep acting significantly influenced in a positive way work engagement (path coefficient = 0.64, p < 0.001). Therefore, H1 was confirmed. It was also proved that POS significantly influenced in a positive way work engagement (path coefficient = −0.13, p < 0.001). Thus, H2 was confirmed. Besides, self-efficacy significantly influenced in a positive way work engagement (path coefficient = 0.22, p < 0.001). Hence, H3 was confirmed. Finally, work engagement significantly influenced in a positive way service quality (path coefficient = 0.16, p < 0.001). Consequently, H4 was confirmed.

Figure 2.

Path analysis of this study. Note. *** p < 0.001.

5.5. Sobel Test

It was recommended to take advantage of the mathematical equation of the Sobel test to assess the significance of indirect impact. A z-value higher than 1.96 (z > 1.96) indicates that the mediating effect is significant [119,120]. Consequently, the relationship between deep acting and service quality is significantly mediated by work engagement (z = 3.82, p <.001). Secondly, POS and service quality are significantly mediated by work engagement (z = 2.59, p < 0.01). Finally, the relationship between self-efficacy and service quality is also mediated by work engagement (z = 3.24, p < 0.01). In brief, deep acting, POS, and self-efficacy exerted a greater total effect on service quality, with indirect effects mediated through work engagement. Hence, it confirmed that there were mediating effects of work engagement for deep acting, POS, and self-efficacy on service quality. Accordingly, H5a, H5b, and H5c were supported (refer to Table 6).

Table 6.

Results of hypotheses testing.

6. Discussion

6.1. Evaluation of Findings

The results suggested that deep acting, POS, and self-efficacy significantly influenced in a positive way work engagement and that work engagement significantly influenced in a positive way service quality. Firstly, on the basis of the emotion regulation framework of Grandey [30], if HFLEs are required to express their positive emotions, this will have a positive outcome, leading to work engagement, which is consistent with Humphrey, Ashforth and Diefendorff [18]. Secondly, when HFLEs perceive they are supported by the organization, their work engagement significantly increases. The finding is in line with those of two recent studies, demonstrating HFLEs’ levels of work engagement were affected by the degrees of POS, and HFLEs would increase and maintain the quality and quantity of their work [94,95]. Thirdly, HFLEs with strong beliefs toward themselves were proved to significantly increase their work engagement, echoing with the study of Huertas-Valdivia, Llorens-Montes and Ruiz-Moreno [62]. Lastly, although the effect of work engagement on service quality had not been addressed so far, in this study, work engagement was proved to have a significantly positive influence on service quality. Namely, those HFLEs who immerse themselves into a pleasant work atmosphere will provide better service quality. Finally, in terms of HFLEs’ work engagement as a core mediator, this study revealed that work engagement significantly mediates the effects of deep acting, POS, and self-efficacy on service quality. In addition, the mediating role of work engagement in this study is also confirmed by the findings of other similar research [22,94,105]. The principles of the COR theory [85] and the JD-R model [17] were empirically tested by the proposed model in this study. That is, deep acting, POS, and self-efficacy are considered positive resources and contribute to work engagement, which will have positive influences on service quality and will lead to resource caravans.

6.2. Theoretical Implications

This study provides valuable academic implications, since it enriches the empirical information about the mediating effect of work engagement under the COR theory and the JD-R model. HFLEs had multifunctional job-related tasks, antisocial working hours, and even low pay, leading to high turnover rates, health alerts, and low service quality [121]. Unlike other previous other studies, this study emphasizes how to decrease the negative influences of the aforementioned situations, organizations should focus on positive behaviors, which means they should find out practical yet natural methods that would be able to increase employees’ potential and promote their career development [17]. Additionally, this study investigated antecedents and outcomes of work engagement, as it was considered a critical factor influencing the job-related well-being of employees and firms in response to research calls [17,97].

Despite the fact that little research has discussed HFLEs’ work engagement as a mediator, on the basis of our careful literature review, none of the studies has examined the mediating effect of work engagement on service quality. Since service quality was seen as one of the critical keys to a successful hospitality business, and frontline employees were valued for their core role to deliver it [122], how to inspire HFLEs to engage in their work and perform service quality was the main concern of this study. Consequently, HFLEs’ deep acting, POS, and self-efficacy were empirically tested, being considered positive antecedents of work engagement and they, in turn, demonstrated positive influences on service quality leading to resource caravans according to the COR theory and the JD-R model. This finding enriches the antecedents and consequences of work engagement in a limited number of empirical studies.

6.3. Managerial Implications

Since work engagement has been considered a critical mediator influencing HFLEs’ outcomes, enhancing it has become challenging for organizations in today’s competitive hospitality industry. Three practical implications are suggested for human resource strategic planning as well as organizations. First, although it is encouraged to authorize employees to be spontaneous in their works, employee orientation and employee training are still essential to offer a proper performance guidance. Second, it is important to always make sure HFLEs feel supported by their supervisor and their company, for they do not distinguish between supervisor and company. Once they perceive organizational support, they will perform better in their job. Third, blaming is not the best way to fix mistakes, while compliments are a good way to improve moods and attitudes.

In addition to these three suggestions, this study also recommends conducting sustainable HRM to combine the selected positive resources into HPWS. Although HPWS was designed to increase both HFLEs’ outcomes and company’s profits, it should be noted that the hospitality industry is not suitable for some HPWS indicators, such as employment security, grievance procedures, job design, etc. [123]. From the view of the social exchange theory, HPWS significantly influences employee’s attitudes and behaviors. As a result, it ultimately contributes to higher levels of organizational citizen behaviors [124], which are regarded as margin benefits for promoting the effective functioning of organizations.

6.4. Research Limitations and Future Suggestions

Owing to lack of time and funding, employees themselves measured the dimension of service quality. For instance, employees were asked “I could well dress and appear neat at work.” Nonetheless, service quality still passed the Cronbach’s alpha and CFA tests, indicating its measurement possessed significant reliability and validity. In addition, other similar researches conducting self-measurements can be found in the literature [29,125]. Another limitation is the overall conceptual model values were slightly lower than the results of path analysis. Therefore, observable variables were analyzed in the second step of structural equation modeling instead of latent variables. However, all path coefficients were characterized by p-values lower than 0.001.

Since data were collected from HFLEs in 3–5-star hotels and restaurants in Taiwan by a random stratified sampling, participants from other countries were qualified to answer the questionnaire as well. Although effective participants of this study included few foreign employees from Australia, Japan, Malaysia, and Thailand, Taiwanese were the most numerous participants. Accordingly, cross-cultural issues can be examined with this model to evaluate the universality of the findings across the world.

7. Conclusions

In the past, profitability dominated everything, but financial outcomes and human management have recently taken over its place with the emergence of sustainable HRM. Additionally, the service industry is highly competitive, particularly the hospitality industry. Consequently, HFLEs are valuable for the hospitality business. The goal of this study, on one hand, was to motivate HFLEs to deliver satisfying service quality and make customers feel a unique and memorable service experience. On the other hand, to inspire HFLEs’ willingness to remain in a firm and to be engaged in their work in the long term. In other words, the former was to make employees feel like volunteers so to perform well, which can benefit the company, whilst the latter focused on making employees immerse themselves into their work, so to augment their intention to stay. Accordingly, three positive resources were selected, i.e., deep acting, POS, and self-efficacy as the antecedents of work engagement. The proposed research model was examined under the COR theory and the JD-R model. Empirical results indicated that service quality was indirectly influenced by deep acting, POS, and self-efficacy via work engagement, enriching the limited hospitality literature. The findings also suggested that hospitality practitioners should start a new phase, reconsidering the importance of employees’ well-being, which can lead to reducing HFLEs’ high turnover intentions and to pleasurable job outcomes. Finally, the combination of the selected positive resources and HPWS suggested in managerial implications can assist an organization to attract and to keep high-quality employees. Since HFLEs play a vital role in the hospitality industry, satisfying them is a priority to sustain a business. Sustainable HRM is, therefore, considered a survival strategy to maintain a successful enterprise in the long term.

Author Contributions

The proposed research framework was conceptualized by C.-J.W. The structure of this study was discussed by C.-J.W. and K.-J.T. This article was written by K.-J.T.

Funding

This project was sponsored by National Pingtung University of Science and Technology.

Acknowledgments

We sincerely appreciate the valuable comments of anonymous reviewers and editors.

Conflicts of Interest

We declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Evans, N.; Stonehouse, G.; Campbell, D. Strategic Management for Travel and Tourism; Taylor & Francis: Oxford, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, P.B.; Gazzoli, G.; Qu, H.; Kim, C.S. Influence of the work relationship between frontline employees and their immediate supervisor on customers’ service experience. J. Hosp. Mark. Manag. 2016, 25, 425–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wirtz, J.; Heracleous, L.; Pangarkar, N. Managing human resources for service excellence and cost effectiveness at singapore airlines. Manag. Serv. Qual. Int. J. 2008, 18, 4–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luthans, F.; Avolio, B.J.; Avey, J.B.; Norman, S.M. Positive psychological capital: Measurement and relationship with performance and satisfaction. Pers. Psychol. 2007, 60, 541–572. [Google Scholar]

- Myers, D.G. The funds, friends, and faith of happy people. Am. Psychol. 2000, 55, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luthans, F. The need for and meaning of positive organizational behavior. J. Organ. Behav. 2002, 695–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Ghiselli, R. Why do you feel stressed in a “smile factory”? Hospitality job characteristics influence work–family conflict and job stress. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2016, 28, 305–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.J.; Ok, C. Reducing burnout and enhancing job satisfaction: Critical role of hotel employees’ emotional intelligence and emotional labor. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2012, 31, 1101–1112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Law, J.; Pearce, P.L.; Woods, B.A. Stress and coping in tourist attraction employees. Tour. Manag. 1995, 16, 277–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karatepe, O.M. The effects of work overload and work-family conflict on job embeddedness and job performance: The mediation of emotional exhaustion. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2013, 25, 614–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.-S.; Huang, W.-S.; Yang, C.-T.; Chiang, M.-J. Work–leisure conflict and its associations with well-being: The roles of social support, leisure participation and job burnout. Tour. Manag. 2014, 45, 244–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakker, A.B.; Schaufeli, W.B. Positive organizational behavior: Engaged employees in flourishing organizations. J. Organ. Behav. Int. J. Ind. Occup. Organ. Psychol. Behav. 2008, 29, 147–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baum, T.; Cheung, C.; Kong, H.; Kralj, A.; Mooney, S.; Ramachandran, S.; Dropulić Ružić, M.; Siow, M. Sustainability and the tourism and hospitality workforce: A thematic analysis. Sustainability 2016, 8, 809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hobfoll, S.E. Conservation of resources: A new attempt at conceptualizing stress. Am. Psychol. 1989, 44, 513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hobfoll, S.E. The influence of culture, community, and the nested-self in the stress process: Advancing conservation of resources theory. Appl. Psychol. 2001, 50, 337–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakker, A.B.; Demerouti, E. The job demands-resources model: State of the art. J. Manag. Psychol. 2007, 22, 309–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakker, A.B.; Demerouti, E. Towards a model of work engagement. Career Dev. Int. 2008, 13, 209–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Humphrey, R.H.; Ashforth, B.E.; Diefendorff, J.M. The bright side of emotional labor. J. Organ. Behav. 2015, 36, 749–769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.-J.; Chen, M.-L. Factors affecting the hotel’s service quality: Relationship marketing and corporate image. J. Hosp. Mark. Manag. 2014, 23, 77–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karatepe, O.M.; Olugbade, O.A. The effects of job and personal resources on hotel employees’ work engagement. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2009, 28, 504–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, D.J.; Lim, V.K. Strength in adversity: The influence of psychological capital on job search. J. Organ. Behav. 2012, 33, 811–839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, H.J.A.; Busser, J.A. Impact of service climate and psychological capital on employee engagement: The role of organizational hierarchy. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2018, 75, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gracia, E.; Salanova, M.; Grau, R.; Cifre, E. How to enhance service quality through organizational facilitators, collective work engagement, and relational service competence. Eur. J. Work Organ. Psychol. 2013, 22, 42–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.-J. Linking sustainable human resource management in hospitality: An empirical investigation of the integrated mediated moderation model. Sustainability 2019, 11, 1066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kramar, R. Beyond strategic human resource management: Is sustainable human resource management the next approach? Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2014, 25, 1069–1089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Prins, P.; Van Beirendonck, L.; De Vos, A.; Segers, J. Sustainable hrm: Bridging theory and practice through the’respect openness continuity (roc)’-model. Manag. Revue 2014, 263–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dao, V.; Langella, I.; Carbo, J. From green to sustainability: Information technology and an integrated sustainability framework. J. Strateg. Inf. Syst. 2011, 20, 63–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bányai, T.; Landschützer, C.; Bányai, Á. Markov-chain simulation-based analysis of human resource structure: How staff deployment and staffing affect sustainable human resource strategy. Sustainability 2018, 10, 3692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horng, J.-S.; Wang, C.-J.; Liu, C.-H.; Chou, S.-F.; Tsai, C.-Y. The role of sustainable service innovation in crafting the vision of the hospitality industry. Sustainability 2016, 8, 223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grandey, A.A. Emotional regulation in the workplace: A new way to conceptualize emotional labor. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 2000, 5, 95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hochschild. The Managed Heart; University of California Press: Berkeley, CA, USA, 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Morris, J.A.; Feldman, D.C. The dimensions, antecedents, and consequences of emotional labor. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1996, 21, 986–1010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashforth, B.E.; Humphrey, R.H. Emotional labor in service roles: The influence of identity. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1993, 18, 88–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gross, J.J. The emerging field of emotion regulation: An integrative review. Rev. Gen. psychol. 1998, 2, 271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brotheridge, C.M.; Grandey, A.A. Emotional labor and burnout: Comparing two perspectives of “people work”. J. Vocat. Behav. 2002, 60, 17–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, J.A.; Diefendorff, J.M.; Ma, Y. Differences in emotional labor across cultures: A comparison of chinese and us service workers. J. Bus. Psychol. 2014, 29, 21–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.L.; Chiaburu, D.S.; Zhang, X.-A.; Li, N.; Grandey, A.A. Rising to the challenge: Deep acting is more beneficial when tasks are appraised as challenging. J. Appl. Psychol. 2015, 100, 1398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hofmann, V.; Stokburger-Sauer, N.E. The impact of emotional labor on employees’ work-life balance perception and commitment: A study in the hospitality industry. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2017, 65, 47–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisenberger, R.; Huntington, R.; Hutchison, S.; Sowa, D. Perceived organizational support. J. Appl. Psychol. 1986, 71, 500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rhoades, L.; Eisenberger, R. Perceived organizational support: A review of the literature. J. Appl. Psychol. 2002, 87, 698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farh, J.-L.; Hackett, R.D.; Liang, J. Individual-level cultural values as moderators of perceived organizational support–employee outcome relationships in china: Comparing the effects of power distance and traditionality. Acad. Manag. J. 2007, 50, 715–729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shore, L.M.; Tetrick, L.E. A construct validity study of the survey of perceived organizational support. J. Appl. Psychol. 1991, 76, 637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Witt, L.A. Exchange ideology as a moderator of job attitudes-organizational citizenship behaviors relationships 1. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 1991, 21, 1490–1501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chew, Y.T.; Wong, S.K. Effects of career mentoring experience and perceived organizational support on employee commitment and intentions to leave: A study among hotel workers in malaysia. Int. J. Manag. 2008, 25, 692. [Google Scholar]

- Karatepe, O.M. Do job resources moderate the effect of emotional dissonance on burnout? A study in the city of ankara, turkey. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2011, 23, 44–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A. Self-efficacy: Toward a unifying theory of behavioral change. Psychol. Rev. 1977, 84, 191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kear, M. Concept analysis of self-efficacy. Grad. Res. Nurs. 2000, 2, 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Bandura, A. Social cognitive theory of self-regulation. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 1991, 50, 248–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iskandar, T.M.; Sanusi, Z.M. Assessing the effects of self-efficacy and task complexity on internal control audit judgment. Asian Acad. Manag. J. Account. Financ. 2011, 7, 29–52. [Google Scholar]

- Blecharz, J.; Luszczynska, A.; Scholz, U.; Schwarzer, R.; Siekanska, M.; Cieslak, R. Predicting performance and performance satisfaction: Mindfulness and beliefs about the ability to deal with social barriers in sport. Anxiety Stress Coping 2014, 27, 270–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLennan, B.; McIlveen, P.; Perera, H.N. Pre-service teachers’ self-efficacy mediates the relationship between career adaptability and career optimism. Teach. Teach. Educ. 2017, 63, 176–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joo, Y.-J.; Bong, M.; Choi, H.-J. Self-efficacy for self-regulated learning, academic self-efficacy, and internet self-efficacy in web-based instruction. Educ. Technol. Res. Dev. 2000, 48, 5–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimmerman, B.J.; Bandura, A.; Martinez-Pons, M. Self-motivation for academic attainment: The role of self-efficacy beliefs and personal goal setting. Am. Educ. Res. J. 1992, 29, 663–676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, R.J.C.; Tsai, C.C. Self-directed learning readiness, internet self-efficacy and preferences towards constructivist internet-based learning environments among higher-aged adults. J. Comput. Assist. Learn. 2009, 25, 489–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basereh, N.; Pishkar, K. Self-directed learning and self-efficacy belief among iranian efl learners at the advanced level of language proficiency. J. Appl. Linguist. Lang. Res. 2016, 3, 232–240. [Google Scholar]

- Lunenburg, F.C. Self-efficacy in the workplace: Implications for motivation and performance. Int. J. Manag. Bus. Adm. 2011, 14, 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Hartline, M.D.; Ferrell, O.C. The management of customer-contact service employees: An empirical investigation. J. Mark. 1996, 52–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karatepe, O.M.; Arasli, H.; Khan, A. The impact of self-efficacy on job outcomes of hotel employees: Evidence from northern cyprus. Int. J. Hosp. Tour. Adm. 2007, 8, 23–46. [Google Scholar]

- Kanten, P. The antecedents of job crafting: Perceived organizational support, job characteristics and self-efficacy. Eur. J. Bus. Soc. Sci. 2014, 3, 113–128. [Google Scholar]

- Salanova, M.; Lorente, L.; Chambel, M.J.; Martínez, I.M. Linking transformational leadership to nurses’ extra-role performance: The mediating role of self-efficacy and work engagement. J. Adv. Nurs. 2011, 67, 2256–2266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, N.; Barling, J.; Zacharatos, A. Positive psychology at work. Handb. Posit. Psychol. 2002, 52, 715–728. [Google Scholar]

- Huertas-Valdivia, I.; Llorens-Montes, F.J.; Ruiz-Moreno, A. Achieving engagement among hospitality employees: A serial mediation model. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2018, 30, 217–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Putra, E.D.; Cho, S.; Liu, J. Extrinsic and intrinsic motivation on work engagement in the hospitality industry: Test of motivation crowding theory. Tour. Hosp. Res. 2017, 17, 228–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Ok, C.M. Hotel employee work engagement and its consequences. J. Hosp. Mark. Manag. 2016, 25, 133–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seligman, M.E.P.; Csikszentmihalyi, M. Positive psychology: An introduction. Am. Psychol. 2000, 55, 5–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schaufeli, W.B.; Salanova, M.; González-Romá, V.; Bakker, A.B. The measurement of engagement and burnout: A two sample confirmatory factor analytic approach. J. Happiness Stud. 2002, 3, 71–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hallberg, U.E.; Schaufeli, W.B. “Same same” but different? Can work engagement be discriminated from job involvement and organizational commitment? Eur. Psychol. 2006, 11, 119–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saks, A.M. Antecedents and consequences of employee engagement. J. Manag. Psychol. 2006, 21, 600–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- May, D.R.; Gilson, R.L.; Harter, L.M. The psychological conditions of meaningfulness, safety and availability and the engagement of the human spirit at work. J. Occup. Organ. Psychol. 2004, 77, 11–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakker, A.B.; Oerlemans, W. Subjective well-being in organizations. In The Oxford Handbook of Positive Organizational Scholarship; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2011; pp. 178–189. [Google Scholar]

- Grönroos, C. A service quality model and its marketing implications. Eur. J. Mark. 1984, 18, 36–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lehtinen, U.; Lehtinen, J.R. Service Quality: A Study of Quality Dimensions; Service Management Institute: Helsinki, Finland, 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Cronin Jr, J.J.; Taylor, S.A. Measuring service quality: A reexamination and extension. J. Mark. 1992, 55–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brady, M.K.; Cronin, J.J., Jr. Some new thoughts on conceptualizing perceived service quality: A hierarchical approach. J. Mark. 2001, 65, 34–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edvardsson, B. Service quality: Beyond cognitive assessment. Manag. Serv. Qual. Int. J. 2005, 15, 127–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schembri, S.; Sandberg, J. The experiential meaning of service quality. Mark. Theory 2011, 11, 165–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, S.K.; Lassar, W.M.; Ganguli, S.; Nguyen, B.; Yu, X. Measuring service quality: A systematic review of literature. Int. J. Serv. Econ. Manag. 2015, 7, 24–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brady, M.K.; Cronin, J.J., Jr.; Brand, R.R. Performance-only measurement of service quality: A replication and extension. J. Bus. Res. 2002, 55, 17–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seth, N.; Deshmukh, S.; Vrat, P. Service quality models: A review. Int. J. Qual. Reliab. Manag. 2005, 22, 913–949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, C.; Lai, F.; Chen, Y.; Hutchinson, J. Conceptualising the perceived service quality of public utility services: A multi-level, multi-dimensional model. Total Qual. Manag. Bus. Excell. 2008, 19, 1055–1070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berry, T.H. Managing the Total Quality Transformation; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Frochot, I.; Hughes, H. Histoqual: The development of a historic houses assessment scale. Tour. Manag. 2000, 21, 157–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrington, M.N.; Olsen, M.D. Concept of service in the hospitality industry. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 1987, 6, 131–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong Ooi Mei, A.; Dean, A.M.; White, C.J. Analysing service quality in the hospitality industry. Manag. Serv. Qual. Int. J. 1999, 9, 136–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halbesleben, J.R.; Neveu, J.-P.; Paustian-Underdahl, S.C.; Westman, M. Getting to the “cor” understanding the role of resources in conservation of resources theory. J. Manag. 2014, 40, 1334–1364. [Google Scholar]

- Hobfoll, S.E. Social and psychological resources and adaptation. Rev. Gen. Psychol. 2002, 6, 307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xanthopoulou, D.; Bakker, A.B.; Demerouti, E.; Schaufeli, W.B. The role of personal resources in the job demands-resources model. Int. J. Stress Manag. 2007, 14, 121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakker, A.B.; Schaufeli, W.B.; Leiter, M.P.; Taris, T.W. Work engagement: An emerging concept in occupational health psychology. Work Stress 2008, 22, 187–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheung, F.Y.-L.; Tang, C.S.-K. Quality of work life as a mediator between emotional labor and work family interference. J. Bus. Psychol. 2009, 24, 245–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, X.; Guy, M.E. How emotional labor and ethical leadership affect job engagement for chinese public servants. Public Pers. Manag. 2014, 43, 3–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, K.-Y.; Chang, C.-W.; Wang, C.-H. Frontline employees’ passion and emotional exhaustion: The mediating role of emotional labor strategies. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2019, 76, 163–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurtessis, J.N.; Eisenberger, R.; Ford, M.T.; Buffardi, L.C.; Stewart, K.A.; Adis, C.S. Perceived organizational support: A meta-analytic evaluation of organizational support theory. J. Manag. 2017, 43, 1854–1884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karatepe, O.M. Do personal resources mediate the effect of perceived organizational support on emotional exhaustion and job outcomes? Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2015, 27, 4–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, H.S.; Yoon, H.H. Improving frontline service employees’ innovative behavior using conflict management in the hospitality industry: The mediating role of engagement. Tour. Manag. 2018, 69, 498–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Huang, Q. The dark side of feeling trusted for hospitality employees: An investigation in two service contexts. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2019, 76, 122–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paek, S.; Schuckert, M.; Kim, T.T.; Lee, G. Why is hospitality employees’ psychological capital important? The effects of psychological capital on work engagement and employee morale. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2015, 50, 9–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karatepe, O.M.; Karadas, G. Do psychological capital and work engagement foster frontline employees’ satisfaction? A study in the hotel industry. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2015, 27, 1254–1278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xanthopoulou, D.; Bakker, A.B.; Fischbach, A. Work engagement among employees facing emotional demands: The role of personal resources. J. Pers. Psychol. 2013, 12, 74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakker, A.B.; Demerouti, E.; Verbeke, W. Using the job demands-resources model to predict burnout and performance. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2004, 43, 83–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slåtten, T.; Mehmetoglu, M. Antecedents and effects of engaged frontline employees: A study from the hospitality industry. Manag. Serv. Qual. Int. J. 2011, 21, 88–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christensen Hughes, J.; Rog, E. Talent management: A strategy for improving employee recruitment, retention and engagement within hospitality organizations. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2008, 20, 743–757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milliman, J.; Gatling, A.; Kim, J.S. The effect of workplace spirituality on hospitality employee engagement, intention to stay, and service delivery. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2018, 35, 56–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karatepe, O.M.; Olugbade, O.A. The mediating role of work engagement in the relationship between high-performance work practices and job outcomes of employees in nigeria. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2016, 28, 2350–2371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Canziani, B.F.; Barbieri, C. Emotional labor in hospitality: Positive affective displays in service encounters. Tour. Hosp. Res. 2018, 18, 242–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karatepe, O.M.; Aga, M. The effects of organization mission fulfillment and perceived organizational support on job performance: The mediating role of work engagement. Int. J. Bank Mark. 2016, 34, 368–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xanthopoulou, D.; Baker, A.B.; Heuven, E.; Demerouti, E.; Schaufeli, W.B. Working in the sky: A diary study on work engagement among flight attendants. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 2008, 13, 345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duane, D.; Consenza Robert, M. Business Research for Decision Making, 6th ed.; Curt Hinrichs: Toronto, ON, Canada, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Nunnally, J. Psychometric Methods; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Haynes, S.N.; Richard, D.; Kubany, E.S. Content validity in psychological assessment: A functional approach to concepts and methods. Psychol. Assess. 1995, 7, 238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, K.H.-L.; Murrmann, S.K. Development and validation of the hospitality emotional labor scale. Tour. Manag. 2006, 27, 1181–1191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwarzer, R.; Jerusalem, M. Optimistic self-beliefs as a resource factor in coping with stress. In Extreme Stress and Communities: Impact and Intervention; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 1995; pp. 159–177. [Google Scholar]

- Schaufeli, W.B.; Bakker, A.B.; Salanova, M. The measurement of work engagement with a short questionnaire: A cross-national study. Educ. Psychol. Meas. 2006, 66, 701–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parasuraman, A.; Zeithaml, V.A.; Berry, L.L. Servqual: A multiple-item scale for measuring consumer perc. J. Retail. 1988, 64, 12. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson, J.C.; Gerbing, D.W. Structural equation modeling in practice: A review and recommended two-step approach. Psychol. Bull. 1988, 103, 411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, T.A. Confirmatory Factor Analysis for Applied Research; Guilford Publications: New York, NY, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Sobel, M.E. Asymptotic confidence intervals for indirect effects in structural equation models. Sociol. Methodol. 1982, 13, 290–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Black, W.C.; Babin, B.J.; Anderson, R.E.; Tatham, R.L. Multivariate Data Analysis; Pearson Prentice Hall: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 2006; Volume 6. [Google Scholar]

- MacKinnon, D.P.; Lockwood, C.M.; Hoffman, J.M.; West, S.G.; Sheets, V. A comparison of methods to test mediation and other intervening variable effects. Psychol. Methods 2002, 7, 83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preacher, K.J.; Hayes, A.F. Spss and sas procedures for estimating indirect effects in simple mediation models. Behav. Res. Methods Instrum. Comput. 2004, 36, 717–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poulston, J. Hospitality workplace problems and poor training: A close relationship. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2008, 20, 412–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouranta, N.; Chitiris, L.; Paravantis, J. The relationship between internal and external service quality. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2009, 21, 275–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, K.; Torres, E.; Ingram, W.; Hutchinson, J. A review of high performance work practices (hpwps) literature and recommendations for future research in the hospitality industry. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2018, 30, 365–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Messersmith, J.G.; Patel, P.C.; Lepak, D.P.; Gould-Williams, J.S. Unlocking the black box: Exploring the link between high-performance work systems and performance. J. Appl. Psychol. 2011, 96, 1105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Babakus, E.; Yavas, U.; Karatepe, O.M.; Avci, T. The effect of management commitment to service quality on employees’ affective and performance outcomes. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2003, 31, 272–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).