Effects of Sports Activity on Sustainable Social Environment and Juvenile Aggression

Abstract

:1. Introduction

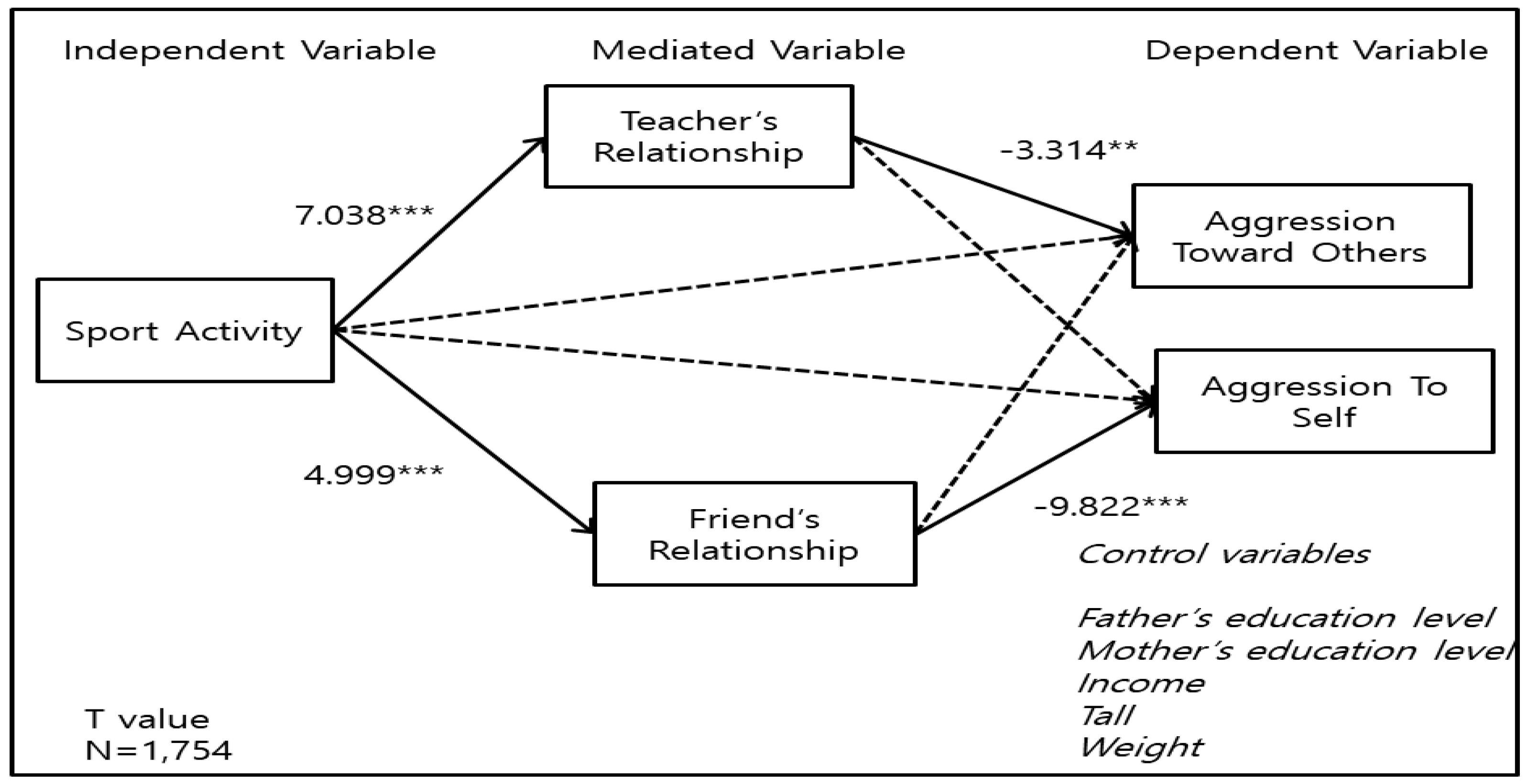

- Are there significant causal relationships between sports activity, sustainable social environment factors (relationships with teachers and friends), and juvenile aggression (toward others and oneself)?

- Is there a mediating effect of sustainable social environment factor (relationships with teachers and friends) between sports activity and juvenile aggression (toward others and oneself)?

2. Materials and Method

2.1. Participants

2.2. Statistical Analysis

2.3. Variable Measure

2.3.1. Control Variable

2.3.2. Independent Variable

2.3.3. Mediating Variable

2.3.4. Dependent Variable

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive Statistics

3.2. The Correlation for Sports Activity, Sustainable Social Environment, and Juvenile Aggression

3.3. Effect of Sports Activity on the Sustainable Social Environment

3.4. Mediating Effect of the Sustainable Social Environment between Sports Activity and Juvenile Aggression

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Back, J.J.; Lee, Y.H. The role of student-teacher relationship on the effects of maltreatment on juvenile delinquency. J. Psychol. 2015, 2, 51–55. [Google Scholar]

- Booth, J.A.; Farrell, A.; Varano, S.P. Social control, serious delinquency, and risky behavior: A gendered analysis. Crime Delinq. 2008, 54, 423–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murray, J.; Farrington, D.P. Risk factors for conduct disorder and delinquency: Key findings from longitudinal studies. Can. J. Psychiatry 2010, 55, 633–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Constance, L.C.; Julia, A.M.; Terceira, A.B. Gender, social bonds, and delinquency: A comparison of boys’ and girls’ models. Soc. Sci. Res. 2005, 23, 357–383. [Google Scholar]

- Coalter, F. Sport-for-change: Some thoughts from a skeptic. Soc. Incl. 2015, 5, 19–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fraser-Thomas, J.L.; Cote, J.; Deakin, J. Youth sports programs: An avenue to foster positive youth development. Phys. Educ. Sport Pedagogy. 2005, 10, 19–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erkut, S.; Allison, J.T. Predicting adolescent self-esteem from participation in school sports among Latino subgroups. Hisp. J. Behav. Sci. 2002, 24, 409–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartmann, D. Theorizing sport as social intervention: A view from the grassroots. Quest 2003, 55, 118–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelly, L. Sports-based interventions and the local governance of youth crime and antisocial behavior. J. Sport Soc. Issues 2013, 37, 261–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feldman, A.; Jennifer, M. The role of school-based extracurricular activities in adolescent development a comprehensive review and future direction. Rev. Educ. Res. 2005, 75, 503–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matza, D. Position and behavior patterns of youth. In Handbook of Modern Sociology; Robert, E.L., Ed.; Rand McNally: Chicago, IL, USA, 1964; pp. 55–62. [Google Scholar]

- Mary, E.D. Sport, and emotions. In Handbook of Sports Studies; Coakley, J., Dunning, E., Eds.; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2000; pp. 477–479. [Google Scholar]

- Mutz, M.; Baur, J. The role of sports in violence prevention: Sports club participation and violent behavior among adolescents. Int. J. Sports Policy Politics 2009, 1, 305–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jo, E.J. The Mediation Effects of Attachment on the Relationship between Adolescent’s Self-efficacy and School Adjustment. Korean J. Youth Stud. 2008, 15, 299–321. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, J.R. Relationships between Peer Conformity and Delinquency in Middle School Students: The Mediating Effects of Self-Control and the Moderating Effects of Attachment to Teachers. Master’s Thesis, Graduate School of Dankook University, Cheonan, Korea, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Connor, E.E.; Dearing, E.; Brian, A.C. Teacher-child relationship and behavior problem trajectories in elementary school. Am. Educ. Time Delinq. Criminal. 2011, 30, 47–87. [Google Scholar]

- Ali, Y.; Hamid, K.; Moghaddam, M.M. Depression Treatment by benefiting from Aerobic practice in water. In Proceedings of the 2000 Seoul International Sports Science Congress, Seoul, Korea, 16–18 September 2015. [Google Scholar]

- National Youth Policy Institute. KCYPS 1st–7th Waves Survey Data User Guide; National Youth Policy Institute: Seoul, Korea, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Schwery, R.; Cade, D. Sport as a social laboratory to cure anomie and prevent violence. Eur. Sports Manag. Q. 2009, 9, 469–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vermillion, M. Sport participation and adolescent deviance: A Logistic Analysis. Soc. Though Res. 2007, 28, 227–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murdock, T.B. The social context of risk: Status and motivational predictors of alienation in middle school. J. Educ. Psychol. 1999, 91, 38–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roger, C.R.; Andres, W.M. Education, and sports. In Handbook of Sports Studies; Coakley, J., Dunning, E., Eds.; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2000; pp. 276–290. [Google Scholar]

- Fejgin, N. Participation in high school competitive sports: A subversion of school mission or contribution to academic goals? Social. Sports J. 1994, 10, 211–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mckercher, C.M.; Schmidt, M.D.; Sanderson, K.A.; Patton, G.C.; Dwyer, T.; Venn, A.J. Physical activity and depression in young adults. Am. J. Previous Med. 2009, 36, 161–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eitzen, D.S. Social control and sport. In Handbook of Sports Studies; Coakley, J., Dunning, E., Eds.; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2000; pp. 370–381. [Google Scholar]

- Brohm, J. Sport: A Prison of Measured Time; Interlinks: London, UK, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Coakley, J.J. Sport in Society Issues & Controversies, 6th ed.; WCB McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, J.R. Adolescents’ Attachments to Parents, Teachers, and Friends, and Delinquencies. Korean Assoc. Hum. Ecol. 2008, 17, 563–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.J. The Longitudinal Analysis of the Relationship between Teacher Attachment and Students’ Maladjustment to Schools. J. Korean Teach. Educ. 2011, 28, 333–352. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, Y.K.; Lee, J.K. Relationship on health behavior, body image, self-efficacy and depression by regular exercise among elementary school students. Korea J. Sports Sci. 2005, 14, 265–272. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, S.S. The influence of family relationship perceived by adolescents upon depression/anxiety, withdrawn behavior, and aggression: Moderating effect of teacher support and friends support. Korea J. Youth Couns. 2015, 21, 343–364. [Google Scholar]

| Category | Answer | % (n) |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | Boys | 52.9 (1091) |

| Girls | 47.1 (970) | |

| Economic level | High-income class | 27.4 (565) |

| Middle class | 62.9 (1296) | |

| Low-income class | 8.4 (200) | |

| Mother’s education level | High school graduation | 47.4 (918) |

| College graduation | 49.8 (966) | |

| Graduate school graduation | 2.8 (54) | |

| Father’s education level | High school graduation | 41.0 (782) |

| College graduation | 53.4 (1019) | |

| Graduate school graduation | 5.7 (108) |

| Constructs | Measurement Items | Factor Loadings | Component | Eigen Value | CFV |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Friend relationship | Get along well with classmates | 0.825 | 0.681 | 2.233 | 55.829 |

| Say sorry in advance when I fight with a friend | 0.791 | 0.352 | |||

| Lend or share my textbook or materials if classmates do not have it | 0.757 | 0.626 | |||

| My friends follow me when I play or go group activities with them | 0.594 | 0.573 | |||

| Teacher relationship | Say hello warmly when I meet the teacher | 0.85 | 0.581 | 3.321 | 66.417 |

| I feel comfortable to talk with my teacher | 0.839 | 0.705 | |||

| I am glad to meet my teacher out of school | 0.812 | 0.723 | |||

| I feel that my teacher is kind to me | 0.808 | 0.66 | |||

| I hope my homeroom teacher can teach me next year | 0.762 | 0.653 | |||

| Aggression toward others | I sometimes pick on even small things | 0.818 | 0.672 | 3.088 | 51.461 |

| I sometimes disturb other’s works | 0.794 | 0.688 | |||

| I nitpick or run at somebody if he makes me preclude what I want | 0.762 | 0.631 | |||

| Aggression toward self | I sometimes fight due to trivial thing | 0.849 | 0.618 | 1.002 | 68.165 |

| I am sometimes angry all day long | 0.826 | 0.753 | |||

| I sometimes cry without any reason | 0.62 | 0.726 |

| Variables | Range | Mean | SD | Cronbach’s α |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sports Activity | 1–5 | 2.86 | 1.39 | 1 item |

| Friend relationship | 4–16 | 7.32 | 1.74 | 0.722/4 items |

| Teacher relationship | 5–20 | 9.80 | 2.98 | 0.871/5 items |

| Aggression toward others | 3–12 | 8.90 | 1.89 | 0.759/3 items |

| Aggression toward self | 3–12 | 9.50 | 1.83 | 0.752/3 items |

| FR | TR | SA | TO | TS | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Friends relationship (FR) | 1 | 0.512 *** | 0.148 *** | −354 *** | −0.328 *** |

| Teacher relationship (TR) | 1 | 0.133 *** | −0.190 *** | −0.153 *** | |

| Sports Activity (SA) | 1 | −0.033 | −0.059 * | ||

| Aggression Toward others (TO) | 1 | 0.527 *** | |||

| Aggression Toward self (TS) | 1 |

| Variable | Model 1 | Model 2 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | SE | β | B | SE | β | ||

| Independent variable | Constant | 8.171 | 1.042 | 10.412 | 1.818 | ||

| SA | 0.214 | 0.03 | 0.172 *** | 0.265 | 0.053 | 0.123 *** | |

| Control variable | HI | −0.005 | 0 | 0.032 | −0.005 | 0 | −0.009 |

| FE | −0.095 | 0.058 | −0.057 | −0.046 | 0.101 | 0.016 | |

| ME | 0.034 | 0.048 | 0.04 | −0.158 | 0.108 | −0.052 | |

| HT | 0.005 | 0.062 | 0.019 * | −0.003 | 0.012 | −0.008 | |

| WT | 0.007 | 0.005 | 0.046 | −0.009 | 0.008 | −0.034 | |

| Dependent variable | Friends relationship | Teacher relationship | |||||

| R2 | 0.04 | 0.021 | |||||

| F value | 12.225 *** | 6.230 *** | |||||

| Variable | Model 3 | Model 4 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | SE | β | B | SE | β | |||

| Independent variable | Constant | 10.578 | 1.127 | 7.872 | 1.068 | |||

| SA | 0.008 | 0.033 | 0.006 | 0.001 | 0.031 | 0.001 | ||

| FR | −0.222 | 0.03 | −0.205 *** | −0.278 | 0.028 | −0.269 *** | ||

| TR | −0.057 | −0.091 | −0.091 ** | −0.004 | 0.016 | −0.007 | ||

| Control variable | HI | −0.005 | 0.016 | 0.016 | −0.006 | 0 | −0.002 | |

| FE | 0.054 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.015 | 0.058 | 0.009 | ||

| ME | −0.003 | −0.002 | −0.002 | 0.054 | 0.062 | 0.03 | ||

| HT | 0.004 | 0.521 | 0.016 | 0.023 | 0.007 | 0.101 | ||

| WT | −0.006 | −0.036 | −0.036 | −0.005 | 0.005 | −0.035 | ||

| Dependent variable | Aggression toward others | Aggression toward self | ||||||

| R2 | 0.073 | 0.087 | ||||||

| F value | 17.307 *** | 20.810 *** | ||||||

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lee, Y.; Lim, S. Effects of Sports Activity on Sustainable Social Environment and Juvenile Aggression. Sustainability 2019, 11, 2279. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11082279

Lee Y, Lim S. Effects of Sports Activity on Sustainable Social Environment and Juvenile Aggression. Sustainability. 2019; 11(8):2279. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11082279

Chicago/Turabian StyleLee, Younyoung, and Seijun Lim. 2019. "Effects of Sports Activity on Sustainable Social Environment and Juvenile Aggression" Sustainability 11, no. 8: 2279. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11082279

APA StyleLee, Y., & Lim, S. (2019). Effects of Sports Activity on Sustainable Social Environment and Juvenile Aggression. Sustainability, 11(8), 2279. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11082279