Evaluating Comparative Research: Mapping and Assessing Current Trends in Built Heritage Studies

Abstract

1. Introduction

We will support the leveraging of cultural heritage for sustainable urban development and recognize its role in stimulating participation and responsibility. We will promote innovative and sustainable use of architectural monuments and sites, with the intention of value creation, through respectful restoration and adaptation. We will engage indigenous peoples and local communities in the promotion and dissemination of knowledge of tangible and intangible cultural heritage and protection of traditional expressions and languages, including through the use of new technologies and techniques.[4] (p. 22, Article 125)

2. The Landscape of Comparative Heritage Studies

the unmet need is for research that explains how conservation is situated in society—how it is shaped by economic, cultural, and social forces and how, in turn, it shapes society. With this type of research, the field can advance in a positive way by embedding the spheres of conservation within their relevant contexts, informing decision-making processes, fostering links with associated disciplines, and enabling conservation professionals and organizations to respond better in the future….[41] (p. 6)

3. Methodology

- “heritage” and “comparative”;

- “conservation” and “comparative” and “heritage;

- “preservation” and “heritage” and “comparative”;

- “comparative analysis” and “heritage”;

- “comparison” and “heritage”

- “comparative” and “historic buildings.”

- The ‘N’ question: How many jurisdictions are compared?

- Geographic scope: What are the locational attributes of comparisons?

- Comparative scope: Is the comparison cross-national (state-level analysis), cross-local (investigating regions, cities, communities) or a combination of those?

- Degree of structuredness: Is the comparison structured or unstructured?

4. Findings & Analysis

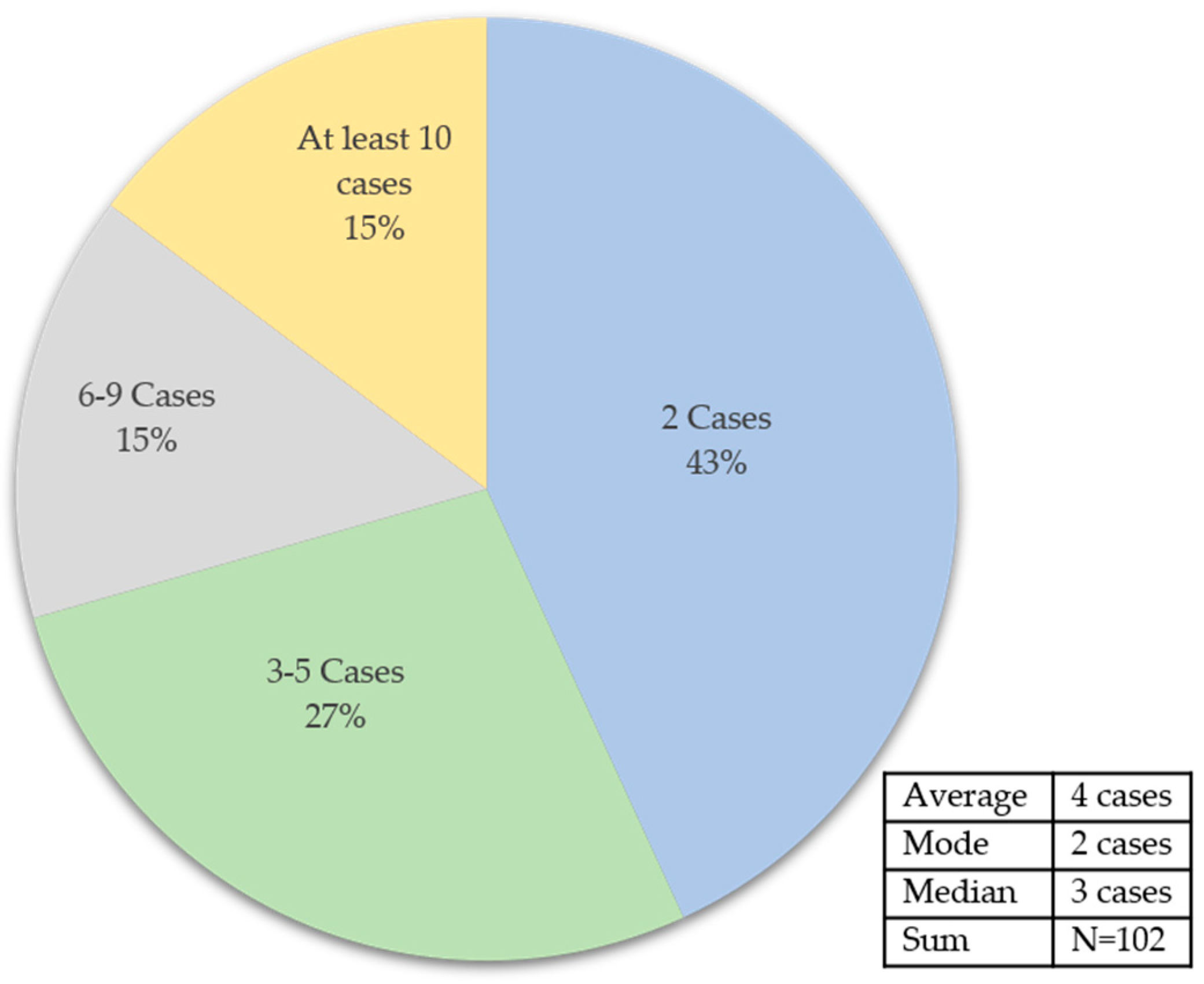

4.1. The ‘N’ Question

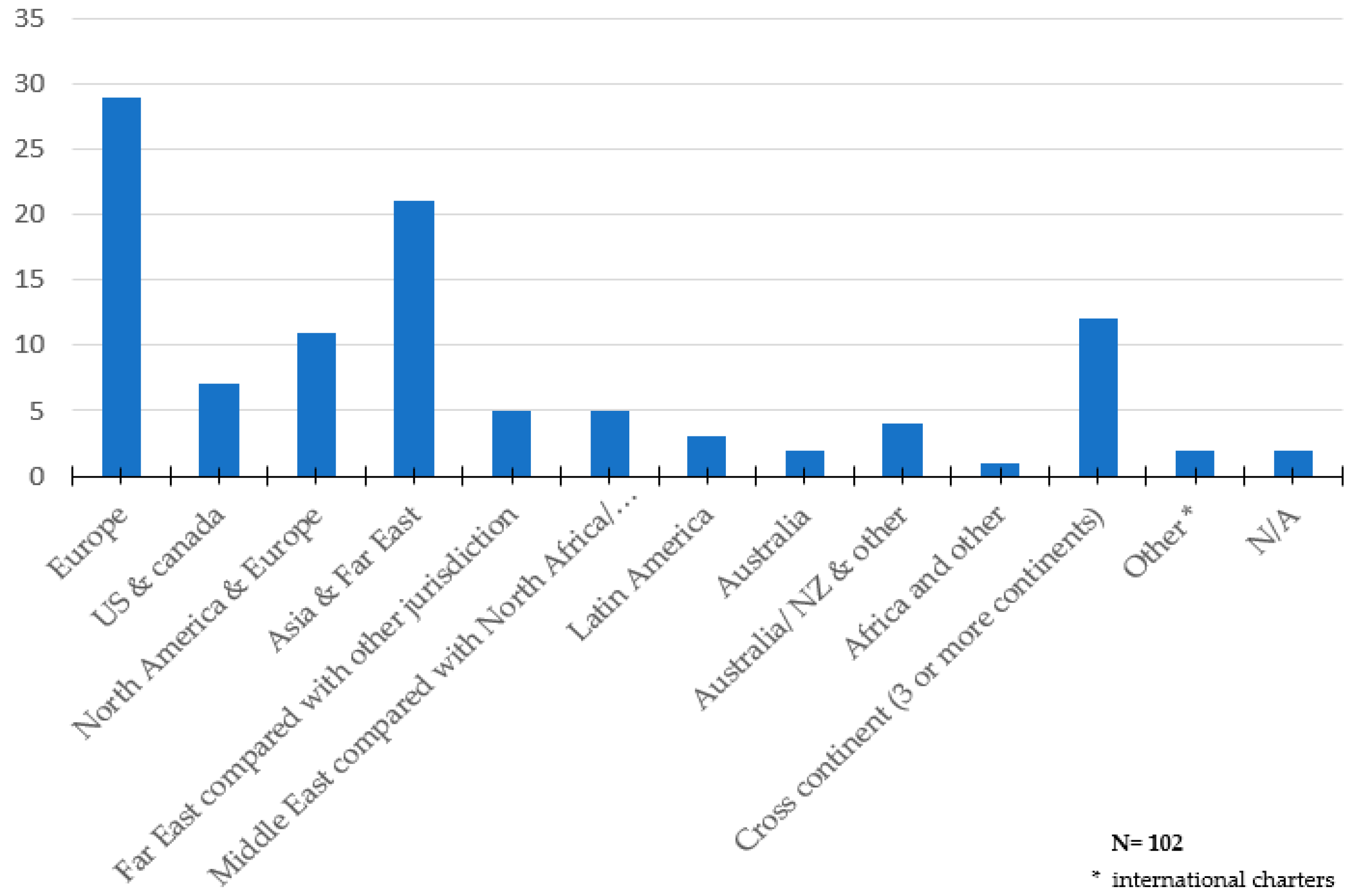

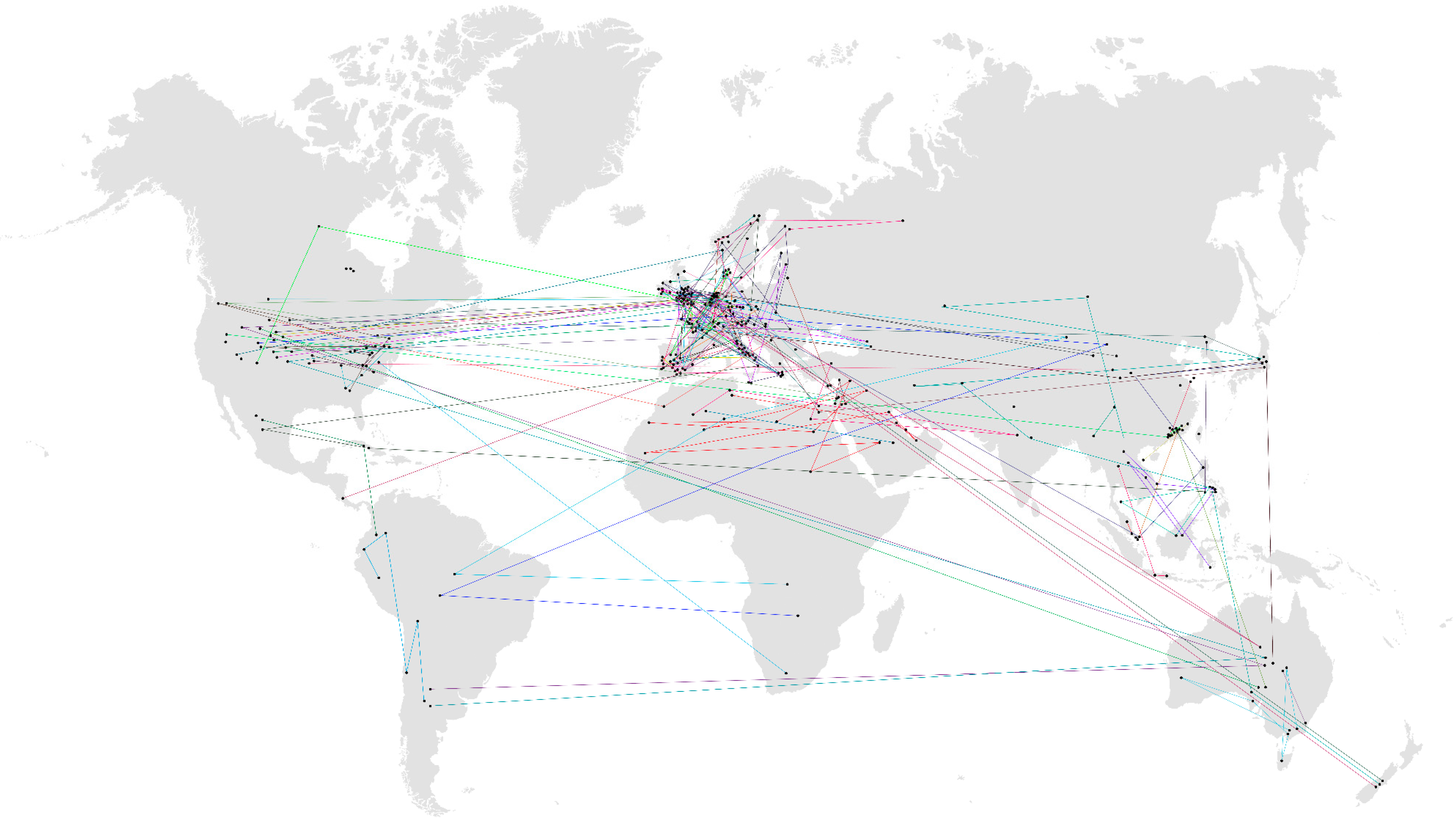

4.2. The Geography of Comparative Heritage Studies

4.3. The Comparative Scope of Built Heritage Studies

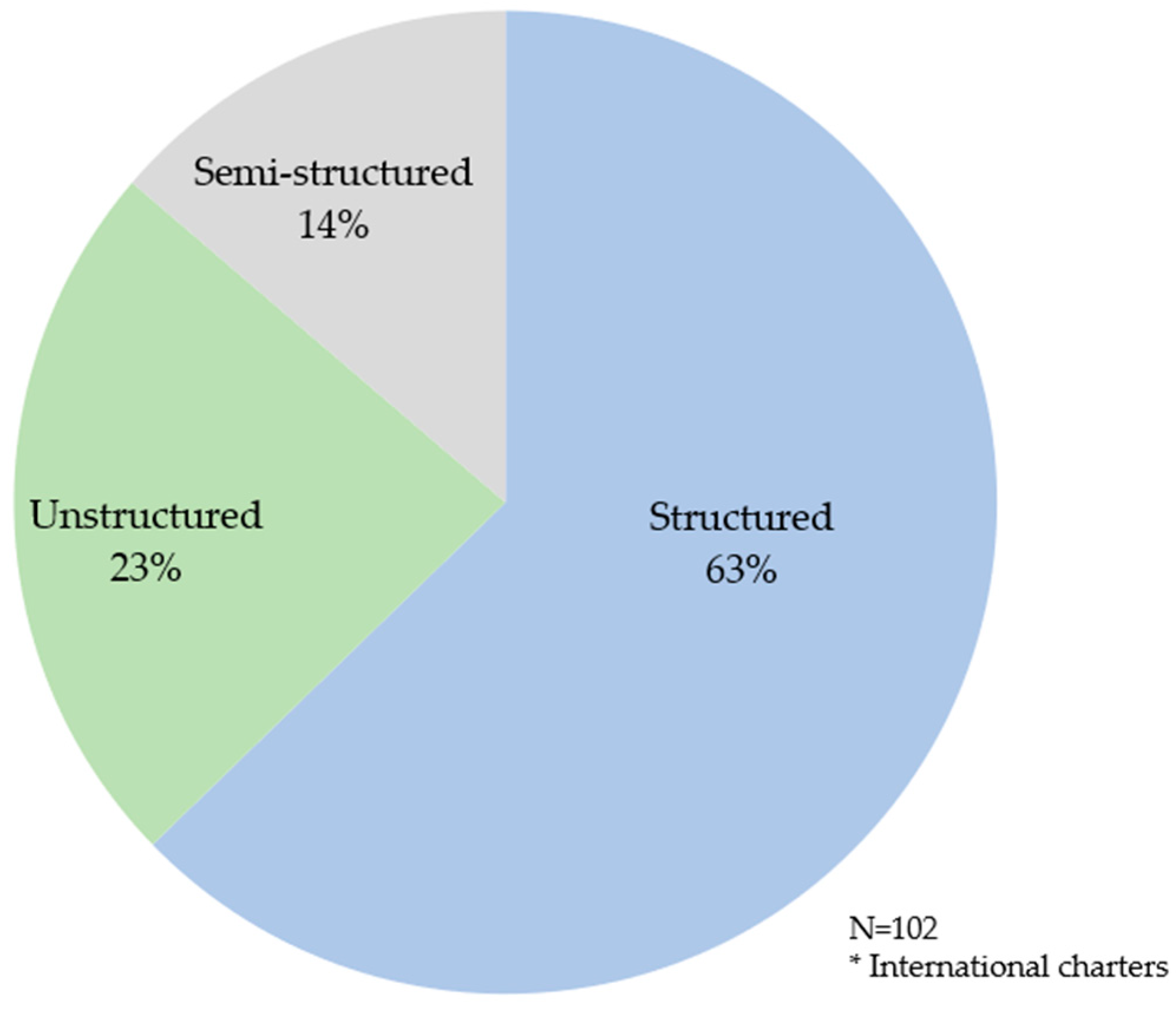

4.4. Degree of Structuredness in Comparative Heritage Studies

5. Conclusions: Comparative Research Concerning Built Heritage Preservation

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Databases Used and Primary Search Results Using Keywords

| Keywords Searched | Web of Science | Science-Direct | EBSCOHost | SSRN | Lexis-Nexis Academic | HeinOnline |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Heritage + comparative | 976 | 10,979 | 42,239 | 12 | 1000 | 21,804 |

| Heritage + Comparative + Conservation | 124 | 3237 | 7904 | 0 | 2099 | 4483 |

| Heritage + Comparative + Preservation | 90 | 2344 | 9239 | 0 | 1332 | 6908 |

| Heritage + comparative analysis | 236 | 2175 | 7269 | 2 | 2085 | 4030 |

| Heritage + comparison | 1766 | 31,397 | 63,721 | 12 | 1467 | 22,266 |

| Historic Buildings + comparative | 31 | 450 | 551 | 0 | 39 | 211 |

- English Heritage—http://www.english-heritage.org.uk/

- Docomomo—http://www.docomomo.com/

- World Bank website—http://www.worldbank.org/

- ICOMOS—http://www.icomos.org/

- Preserve-Net, at Cornell University—http://www.preservenet.cornell.edu/links.html#archives

- Preservation Studies Student Organization—http://www.rso.cornell.edu/psso/theses.html

- Heritage Works—http://www.heritageworks.co.uk/

- National Trust for Historic Preservation—http://www.preservationnation.org/resources/case-studies/

- Advisory Council on Historic Preservation—http://www.achp.gov/pubs.html

- Council of Europe—http://book.coe.int/EN/index.php?PAGEID=17&lang=EN

Appendix B.

| Author & Publication Year | Name of Localities | N | Location | Scope of Comparison | Structuredness | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adie & Hall, 2017 | Independence Hall (USA); Studenica Monastery (Serbia); Volubilis (Morrocco). | 3 | Cross continent | Cross-local/ Cross-national | Structured | [85] |

| Aggarwal & Suklabaidya, 2017 | Two sites in Delhi, India | 2 | Asia & Far East | Cross-local | Semi-structured | [86] |

| Akagawa & Sirisrisak, 2008 | 10 heritage sites in Australia, NZ, The Philippines, India, Afghanistan, Iran, Japan, Kazakhstan, Mongolia, Laos. | 10 | Australia/ NZ & other | Cross-local/ Cross-national | Structured | [87] |

| Ashworth & Howard, 1999 | UK, Spain, the Netherlands, Portugal, France, Italy | 6 | Europe | Cross-national | Structured | [43] |

| Baarvald et al., 2018 | 10 redevelopment projects in the Netherlands. | 10 | Europe | Cross-local | Structured | [88] |

| Balsas, 2013 | Las Vegas & Macau | 2 | Far East compared with other jurisdiction | Cross-local/ Cross-national | Structured | [89] |

| Bamert et al., 2016 | Historic areas in Austria and Switzerland: Kleinwalser Valley & the Safien Valley. | 2 | Europe | Cross-local/ Cross-national | Structured | [90] |

| Barthel, 1996 | USA & Britain | 2 | North America & Europe | Cross-national | Structured | [91] |

| Black & Wall, 2001 | Three religious sites: Borobudur & Prambanan in Indonesia and Ayutthaya in Thailand | 3 | Asia & Far East | Cross-local/ Cross-national | Unstructured | [92] |

| Boer & Wiffen, 2006 | Comparing all Australian states and territories. | 8 | Australia | Cross-national | Structured | [93] |

| Boussaa, 2010 | Saudi Arabia & Algeria | 2 | Middle East and/or North Africa/ Europe | Cross-local/ Cross-national | Unstructured | [94] |

| Bronski & Gabbi, 1999 | Comparing six charters and guidelines for preservation | 6 | n/a | n/a | Structured | [95] |

| Brooks et al., 2014 | UK & China | 2 | Far East compared with other jurisdiction | Cross-national | Structured | [96] |

| Castillo & Menéndez, 2014 | Four Heritage sites in Oaxaca (Mexico), Old Havana (Cuba), Cartagena de Indias (Colombia). | 3 | Latin America | Cross-local/ Cross-national | Unstructured | [97] |

| Corsane et al., 2007 | Five eco-museums in Italy | 5 | Europe | Cross-local | Structured | [98] |

| Cullingworth & Nadin, 2006; Cullingworth et al., 2014 | England, Scotland, Wales, Northern Ireland | 4 | Europe | Cross-national | Structured | [99,100] |

| Curry, 1995 | Kentucky, Georgia, North Carolina & Massachusetts | 4 | USA & Canada | Cross-local | Unstructured | [101] |

| Dann & Steel, 1999 | UK & the Netherlands | 2 | Europe | Cross-national | Unstructured | [102] |

| de Boer, 2006 | Arizona, Norway, Denmark | 3 | North America & Europe | Cross-national | Structured | [103] |

| de Boer, 2009 | Arizona, Norway, Denmark | 3 | North America & Europe | Cross-national | Structured | [104] |

| De Rosa & Di Palma, 2013 | Naples, Valencia, Marseille Liverpool | 4 | Europe | Cross-local/ Cross-national | Structured | [82] |

| Donaghey, 2001 | NZ and England | 2 | Australia/ NZ & other | Cross-national | Structured | [105] |

| Fisch, 2008 | Argentina, Australia, USA, Belgium, France, Greece, Italy, Spain, Germany, UK, the Netherlands. | 11 | Cross continent | Cross-national | Unstructured | [106] |

| Fung et al. 2017 | HK & Macau | 2 | Asia & Far East | Cross-local | Structured | [51] |

| Graezer-Bideau & Kilani, 2012 | Two provinces in Malaysia: Melaka and George Town | 2 | Asia & Far East | Cross-local | Unstructured | [107] |

| Gregory, 2008 | UK and NZ | 2 | Australia/ NZ & other | Cross-local/ Cross-national | Unstructured | [53] |

| Grenvile, 2007 | Britain & Germany / Poland & Germany | 2 | Europe | Cross-local/ Cross-national | Unstructured | [108] |

| Guarneros-Meza, 2008 | Two cities in Mexico: Querétaro and San Luis Potosí | 2 | Latin America | Cross-local | Structured | [109] |

| Gullino & Larcher, 2013 | 14 rural heritage sites in 10 countries: Philippines, Cuba, Mexico, Italy, France, Sweden, Austria, Hungary, Portugal, Switzerland. | 14 | Cross continent | Cross-local/ Cross-national | Structured | [110] |

| Hobson, 2004 | Two towns in England | 2 | Europe | Cross-local | Structured | [76] |

| Holtorf, 2007 | Sweden & Germany | 2 | Europe | Cross-national | Semi-structured | [111] |

| Irsheid, 1997 | Algeria, Iraq, Jordan, Egypt, Morocco, Mauritania, Lybia, Lebanon, Syria, Sudan, Saudi Arabia, Qatar, Kuwait, United Arab Emirates, Bahrain; Tunisia. | 16 | Middle East and/or North Africa/ Europe | Cross-national | Semi-structured | [60] |

| Janssen-Jansen et al., 2008 | Japan, Korea, USA, the Netherlands, Italy, Spain | 6 | Cross continent | Cross-national | Semi-structured | [47] |

| Khirfan, 2010 | Athens & Alexandria | 2 | Middle East and/or North Africa/ Europe | Cross-local/ Cross-national | Structured | [112] |

| Khirfan, 2014 | Acre (Israel), Al-Salt (Jordan), and Aleppo (Syria) | 3 | Middle East and/or North Africa/ Europe | Cross-local/ Cross-national | Structured | [113] |

| King & Hitchcock, 2014 | Comparing World Heritage sites in Thailand, Malaysia and Indonesia. | 3 | Asia & Far East | Cross-local/ Cross-national | Unstructured | [114] |

| King, 2016 | Heritage sites in seven countries in: Laos, Vietnam, the Philippines, Malaysia, Thailand, Cambodia, Indonesia. | 10 | Asia & Far East | Cross-local/ Cross-national | Unstructured | [35] |

| Klamer et al., 2013 | Austria, Belgium, Bulgaria, Cyprus, Denmark, Germany, Malta, Greece, Iceland, Italy, Ireland, Estonia, Slovenia, Latvia, Slovakia, Finland, France, UK, Norway, Romania, Turkey, Japan, Azerbaijan. | 23 | Cross continent | Cross-national | Structured | [115] |

| Kovacs et al., 2015 | 64 conservation districts in Ontario, Canada. | 64 | USA & Canada | Cross-local | Structured | [116] |

| Landorf, 2009 | Six industrial heritage sites in the UK | 6 | Europe | Cross-local | Structured | [117] |

| Last & Shelbourn, 2001 | Scotland & England | 2 | Europe | Cross-national | Structured | [118] |

| Lee, 1996 | Six conservation areas in Singapore | 6 | Asia & Far East | Cross-local | Structured | [119] |

| Lee & du Cros, 2013 | Macau, HK, Guangzhou in China | 3 | Asia & Far East | Cross-local | Semi-structured | [120] |

| Li, 2003 | Singapore & HK | 2 | Asia & Far East | Cross-national | Unstructured | [121] |

| Linantud, 2008 | Memorial sites in South Korea and the Philippines | 2 | Asia & Far East | Cross-local/ Cross-national | Semi-structured | [122] |

| Losson, 2017 | Argentina, Bolivia, Chile, Colombia, Ecuador, Peru | 6 | Latin America | Cross-national | Structured | [123] |

| Lunn, 2007 | Vietnam, Singapore, Thailand; | 3 | Asia & Far East | Cross-local/ Cross-national | Unstructured | [124] |

| Meskell et al. 2015 | Six world regions: Africa, Latin America, Arab States, Asia, Europe/North America. | 6 | Cross continent | Cross-national | Structured | [125] |

| Misirlisoy & Günҫe, 2016 | 16 re-use projects in six countries: Italy, UK, Hungary, Cyprus, France, Austria. | 16 | Europe | Cross-local/ Cross-national | Unstructured | [126] |

| Miura, 2010 | Angkor, Cambodia & Vat Phou, Laos | 2 | Asia & Far East | Cross-local/ Cross-national | Unstructured | [127] |

| Mualam, 2012 | Oregon, England, Israel. | 3 | Cross continent | Cross-local/ Cross-national | Structured | [128] |

| Mualam, 2015 | Five local jurisdictions in Israel | 5 | Middle East and/or North Africa/ Europe | Cross-local | Structured | [129] |

| Mullin et al. 2000 | USA & Portugal | 2 | North America & Europe | Cross-national | Semi-structured | [79] |

| Negussie, 2006 | Stockholm (Sweden) & Dublin (Ireland) | 2 | Europe | Cross-local/ Cross-national | Structured | [130] |

| Ng, 2009 | Shanghai & Shenzhen in China | 2 | Asia & Far East | Cross-local | Unstructured | [131] |

| Nyseth & Sognnæs, 2013 | Three towns in Norway: Stavanger, Mosjøen, Risør | 3 | Europe | Cross-local | Structured | [132] |

| Ornelas et al 2016 | Spain, Portugal, Italy | 3 | Europe | Cross-national | Structured | [133] |

| Parkin, 2007 | USA & England | 2 | North America & Europe | Cross-national | Unstructured | [52] |

| Pettygrove, 2006 | Ireland & US | 2 | North America & Europe | Cross-national | Structured | [48] |

| Phelps et al. 2002 | Sweden, UK, the Netherlands | 3 | Europe | Cross-local/ Cross-national | Semi-structured | [134] |

| PICH Consortium, 2018 | UK, Italy, Norway, the Netherlands | 4 | Europe | Cross-national | Structured | [38] |

| Pickard, 2001 | Belgium, Czech Rep., Denmark, France, Georgia, Germany, Ireland, Italy, Latvia, Malta, Netherlands, Spain, the UK. | 13 | Europe | Cross-national | Structured | [44] |

| Pickard, 2002 | England, France, Denmark, Germany, Spain, Czech Republic | 6 | Europe | Cross-national | Structured | [135] |

| Pickard, 2002 | Belgium, Czech Republic, Denmark, France, Georgia, Germany, Ireland, Netherlands, Spain, UK. | 10 | Europe | Cross-national | Structured | [136] |

| Pickard, 2009 | USA, Canada, UK, Spain, the Netherlands, Germany, France, Denmark, Belgium, Ireland, Italy | 11 | North America & Europe | Cross-national | Unstructured | [50] |

| Poor & Snowball, 2010 | Two university campuses in Maryland (US) and in Rhodes, Eastern Cape Province, South Africa | 2 | Africa & other | Cross-local/ Cross-national | Structured | [137] |

| Prudon, 2008 | USA & Europe | 2 | North America & Europe | Cross-national | Structured | [32] |

| Quintard-Morenas, 2004 | France & Kansas | 2 | North America & Europe | Cross-national | Semi-structured | [138] |

| Rautenberg, 2012 | UK/Wales & France | 2 | Europe | Cross-local/ Cross-national | Semi-structured | [139] |

| Reeves, 1999 | Five municipalities in Southern Nevada | 5 | USA & Canada | Cross-local | Unstructured | [140] |

| Ren & Han, 2018 | UK & China | 2 | Far East compared with other jurisdiction | Cross-local/ Cross-national | Structured | [141] |

| Roth, 2003 | New York City (USA), Berlin (Germany), Tokyo (Japan), Cairo (Egypt) | 4 | Cross continent | Cross-local/ Cross-national | Unstructured | [80] |

| Ryberg-Webster & Kinahan, 2017 | Six cities in the US: Baltimore, Cleveland, Philadelphia, Providence, Richmond & St. Louis | 6 | USA & Canada | Cross-local | Structured | [142] |

| Ryberg-Webster, 2013 | 10 cities in the US: Atlanta (GA), Baltimore (MD), Cleveland (OH), Denver (CO), Philadelphia (PA), Portland (OR), Providence (RI), Richmond (VA), Seattle (WA), St. Louis (MO) | 10 | USA & Canada | Cross-local | Structured | [143] |

| Sande, 2015 | Specific sites in Norway & Sweden (Laponia Area in Norway & Lofoten Islands, Sweden). | 2 | Europe | Cross-local/ Cross-national | Structured | [144] |

| Sanz-Salla, 2009 | UK, US, Spain | 3 | North America & Europe | Cross-national | Unstructured | [49] |

| Seduikyte et al., 2018 | Cyprus & Lithuania | 2 | Europe | Cross-national | Semi-structured | [145] |

| Shelbourn, 2006 | UK & US | 2 | North America & Europe | Cross-national | Structured | [146] |

| Shipley & Reyburn, 2003 | 20 towns in Ontario, Canada. | 20 | USA & Canada | Cross-local | Structured | [147] |

| Shipley & Snyder, 2013 | Two conservation areas in Ontario: Unionville & Markham Village | 2 | USA & Canada | Cross-local | Structured | [148] |

| Simpson & Chapman 1999 | Edinburgh & Prague | 2 | Europe | Cross-local/ Cross-national | Structured | [149] |

| Soane, 2002 | Germany & England | 2 | Europe | Cross-national | Structured | [150] |

| Solomon-Maman, 2005 | USA, Israel, Hungary, Croatia, Sweden, Germany, France, Belgium, Britain | 9 | Cross continent | Cross-national | Structured | [151] |

| Strasser, 2002 | Comparing six world regions: Africa, Latin America, Arab States, Asia, Europe/North America | 6 | Cross continent | Cross-national | Structured | [152] |

| Swenson, 2013 | France, England, Germany | 3 | Europe | Cross-national | Semi-structured | [19] |

| Taylor & Landorf, 2015 | New South Wales and Queensland, Australia | 2 | Australia | Cross-local | Structured | [153] |

| Tweed & Sutherland, 2007 | Belfast, Copenhagen, Liege | 3 | Europe | Cross-local/ Cross-national | Semi-structured | [81] |

| van Oers, 2007 | Four international charters. | 4 | n/a | n/a | Structured | [154] |

| Veldpaus & Roders, 2014 | Seven international heritage treaties | 7 | Cross continent | Cross-national | Structured | [155] |

| Vigneron, 2016 | Australia, Japan, China, France, Germany, Italy, Spain, UK, Switzerland, US. | 10 | Cross continent | Cross-national | Structured | [156] |

| Wah Chan & Lee, 2017 | Two projects in Hong Kong | 2 | Asia & Far East | Cross-local | Unstructured | [157] |

| Wang & Lee, 2008 | Two historic areas in Taiwan | 2 | Asia & Far East | Cross-local | Structured | [158] |

| Wang, 2007 | New Orleans (USA) & Chanting (China) | 2 | Far East compared with other jurisdiction | Cross-local | Structured | [159] |

| Ween, 2012 | Three heritage sites in Norway: Ceávccageádge, Røros, Tysfjord-Hellemo National Park | 3 | Europe | Cross-local | Semi-structured | [160] |

| Whitehand et al., 2011 | TWo conservation areas in Guangzhou, China | 2 | Asia & Far East | Cross-local | Structured | [161] |

| Xu, 2017 | China, Singapore, Japan, Britain, Germany, Italy | 6 | Far East compared with other jurisdiction | Cross-national | Structured | [162] |

| Yang, 2014 | Two cities: Lijiang in China and Bagan, Burma | 2 | Asia & Far East | Cross-local/ Cross-national | Structured | [163] |

| Yu, 2008, | Australia, Hong Kong, Macao | 3 | Australia/ NZ & other | Cross-national | Structured | [61] |

| Yung & Chan, 2011 | Two sites in Hong Kong | 2 | Asia & Far East | Cross-local | Structured | [164] |

| Yung et al., 2014 | Comparing eight projects in Hong Kong. | 8 | Asia & Far East | Cross-local | Structured | [165] |

| Zhang & Wu, 2016 | Three sites in Datangwu village, China | 3 | Asia & Far East | Cross-local | Unstructured | [166] |

| Zhang 2005 | Two historic areas in Shanghaii | 2 | Asia & Far East | Cross-local | Unstructured | [56] |

References

- ICOMOS. The Paris Declaration: On Heritage as the Driver of Development; ICOMOS: Paris, France, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- UNESCO. The Hangzhou Declaration: Placing Culture at the Heart of Sustainable Development Policies; UNESCO: Paris, France, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations General Assembly A/RES/70/1. Transforming Our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development; United Nations General Assembly: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations General Assembly A/RES/71/256. New Urban Agenda; United Nations General Assembly: New York, NY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Landorf, C. Evaluating social sustainability in historic urban environments. Int. J. Herit. Stud. 2011, 17, 463–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fusco Girard, L. Toward a Smart Sustainable Development of Port Cities/Areas: The Role of the “Historic Urban Landscape” Approach. Sustainability 2013, 5, 4329–4348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Oers, R.; Pereira-Roders, A. Historic cities as model of sustainability. J. Cult. Herit. Manag. Sustain. Dev. 2012, 2, 4–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alterman, R. Comparative Analysis: A Platform for Cross-National Learning. In Takings International: A Comparative Perspective on Land Use Regulations and Compensation Rights; Alterman, R., Ed.; ABA Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Theories of Urban Politics, 2nd ed.; Davies, J.S., Imbroscio, D.L., Eds.; SAGE Publications: London, UK, 2009; ISBN 978-0-85702-949-2. [Google Scholar]

- Mukhija, V. N of One plus Some: An Alternative Strategy for Conducting Single Case Research. J. Plan. Educ. Res. 2010, 29, 416–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goetz, E.G. The New Localism from a Cross-National Perspective. In The New Localism: Comparative Urban Politics in a Global Era; Goetz, E.G., Clarke, S.E., Eds.; SAGE Publications: London, UK, 1993; pp. 199–220. ISBN 978-1-4522-5460-9. [Google Scholar]

- Stern, R. Globalisation and Urban Issues in the Non-Western World. In Theories of Urban Politics; Davies, J.S., Imbroscio, D.L., Eds.; SAGE Publications: London, UK, 2009; pp. 153–168. ISBN 978-0-85702-949-2. [Google Scholar]

- A Dictionary of the Social Sciences: Complied under the Auspices of UNESCO; Gould, J., Kolb, W.L., Eds.; Tavistock Pulications: London, UK, 1964. [Google Scholar]

- Weiss, C.H. Evaluation: Methods for Studying Programs and Policies; Prentice Hall: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 1997; ISBN 978-0-13-309725-2. [Google Scholar]

- DiGaetano, A.; Klemanski, J.S. Power and City Governance: Comparative Perspectives on Urban Development; University of Minnesota Press: Minneapolis, MN, USA, 1999; ISBN 978-0-8166-3219-0. [Google Scholar]

- Razin, E. The Impact of Local Government Organization on Development and Disparities—A Comparative Perspective. Environ. Plan. C Gov. Policy 2000, 18, 17–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wollmann, H. Local Government Systems: From Historic Divergence towards Convergence? Great Britain, France, and Germany as Comparative Cases in Point. Environ. Plan. C Gov. Policy 2000, 18, 33–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denters, B.; Mossberger, K. Building Blocks for a Methodology for Comparative Urban Political Research. Urban Aff. Rev. 2006, 41, 550–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swenson, A. The Rise of Heritage: Preserving the Past in France, Germany and England, 1789–1914; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2013; ISBN 978-0-521-11762-3. [Google Scholar]

- Wolman, H. Comparing Local Government Systems across Countries: Conceptual and Methodological Challenges to Building a Field of Comparative Local Government Studies. Environ. Plan. C Gov. Policy 2008, 26, 87–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kantor, P.; Savitch, H.V. How to Study Comparative Urban Development Politics: A Research Note. Int. J. Urban Reg. Res. 2005, 29, 135–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pierre, J. Comparative Urban Governance: Uncovering Complex Causalities. Urban Aff. Rev. 2005, 40, 446–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sybblis, M.; Centeno, M. Sub-Nationalism. Am. Behav. Sci. 2017, 61, 799–807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snyder, R. Scaling Down: The Subnational Comparative Method. Stud. Comp. Int. Dev. 2001, 36, 93–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enriquez, E.; Sybblis, M.; Centeno, M.A. A Cross-National Comparison of Sub-National Variation. Am. Behav. Sci. 2017, 61, 908–931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sellers, J.M. Re-Placing the Nation: An Agenda for Comparative Urban Politics. Urban Aff. Rev. 2005, 40, 419–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wood, A. Comparative urban politics and the question of scale. Space Polity 2005, 9, 201–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weinstock, D. Self-determination for (some) cities? In Arguing about Justice: Essays for Philippe Van Parijs; Gosseries, A., Vanderborght, P., Eds.; Hors Collections; Presses Universitaires de Louvain: Louvain-la-Neuve, Belgium, 2011; pp. 377–386. ISBN 978-2-87558-196-9. [Google Scholar]

- Barber, B.R. If Mayors Ruled the World: Dysfunctional Nations, Rising Cities; Yale University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2013; ISBN 978-0-300-16467-1. [Google Scholar]

- Katz, B.; Nowak, J. The New Localism: How Cities Can Thrive in the Age of Populism; Brookings Institution Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2018; ISBN 978-0-8157-3165-8. [Google Scholar]

- Bulkeley, H.; Luque-Ayala, A.; McFarlane, C.; MacLeod, G. Enhancing urban autonomy: Towards a new political project for cities. Urban Stud. 2018, 55, 702–719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prudon, T.H.M. Preservation of Modern Architecture; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2008; ISBN 978-0-471-66294-5. [Google Scholar]

- Heritage Tourism in Southeast Asia; Hitchcock, M., King, V.T., Parnwell, M., Eds.; NIAS Press: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2010; ISBN 978-0-8248-3505-7. [Google Scholar]

- Howe, K.W. Los Angeles Historic Resource Survey Assessment Project; The Getty Conservation Institute: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- UNESCO in Southeast Asia: World Heritage Sites in Comparative Perspective; King, V.T., Ed.; NIAS Studies in Asian Topics; NIAS Press: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2016; ISBN 978-87-7694-174-1. [Google Scholar]

- Caballero, G.V.A. The role of natural resources in the historic urban landscape approach. J. Cult. Herit. Manag. Sustain. Dev. 2016, 6, 2–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mualam, N.; Alterman, R. Social dilemmas in built-heritage policy: The role of social considerations in decisions of planning inspectors. J. Hous. Built Environ. 2018, 33, 481–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- PICH Consortium. “Cultural Heritage—A Challenge for Europe. The Impact of Urban Planning and Governance Reform on the Historic Built Environment and Intangible Cultural Heritage (PICH)”. 2018. Available online: https://planningandheritage.wordpress.com/pich-2/ (accessed on 15 November 2018).

- Lowenthal, D. The Heritage Crusade and the Spoils of History; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1998; ISBN 978-0-521-63562-2. [Google Scholar]

- Murphy, J.D. Conference Report: The Future of Asia’s Past. Int. J. Cult. Prop. 1995, 4, 369–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avrami, E.; Mason, R.; de la Torre, M. Values and Heritage Conservation; The Getty Conservation Institute: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, G.B. The Care of Ancient Monuments: An Account of Legislative and Other Measures Adopted in European Countries for Protecting Ancient Monuments, Objects and Scenes of Natural Beauty, and for Preserving the Aspect of Historical Cities; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1905; ISBN 978-1-108-01606-3. [Google Scholar]

- European Heritage Planning and Management; Ashworth, G., Howard, P., Eds.; Intellect Ltd.: Exeter, UK, 1999; ISBN 978-1-84150-005-8. [Google Scholar]

- Policy and Law in Heritage Conservation; Pickard, R., Ed.; Spon Press: London, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2001; ISBN 978-0-419-23280-3. [Google Scholar]

- Breeze, D.J. Gerard Baldwin Brown (1849–1932): The recording and preservation of monuments. Proc. Soc. Antiqu. Scotl. 2001, 131, 41–55. [Google Scholar]

- Council of Europe. Monument Protection in Europe; Kluwer B.V.: Deventer, The Netherlands, 1979. [Google Scholar]

- New Instruments in Spatial Planning: An International Perspective on Non-Financial Compensation; Janssen-Jansen, L., Spaans, M., van der Veen, M., Eds.; IOS Press: Delft, The Netherlands, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Pettygrove, J.C. Canyons, Castles & (and) Controversies: A Comparison of Preservation Laws in the United States & (and) Ireland. Regent J. Int. Law 2006, 4, 47–100. [Google Scholar]

- Sanz Salla, C.O. The Protection of Historic Properties: A Comparative Study of Administrative Policies; WIT Press: Southhampton, UK, 2009; ISBN 978-1-84564-404-8. [Google Scholar]

- Pickard, R. Funding the Architectural Heritage: A Guide to Policies and Examples; Council of Europe Press: Strasbourg, France, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Fung, I.W.H.; Tsang, Y.T.; Tam, V.W.Y.; Xu, Y.T.; Mok, E.C.K. A review on historic building conservation: A comparison between Hong Kong and Macau systems. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2017, 71, 927–942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parkin, C. A Comparative Analysis of the Tension Created By Disability Access and Historic Preservation Laws in the United States and England. Conn. J. Int. Law 2007, 22, 379–417. [Google Scholar]

- Gregory, J. Reconsidering Relocated Buildings: ICOMOS, Authenticity and Mass Relocation. Int. J. Herit. Stud. 2008, 14, 112–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Przeworski, A.; Teune, H. The Logic of Comparative Social Inquiry; Wiley—Interscience: New York, NY, USA, 1970; ISBN 978-1-57524-151-7. [Google Scholar]

- Keating, M. Comparative Urban Politics: Power and the City in the United States, Canada, Britain, and France; Edward Elgar Pub.: Aldershot, UK, 1991; ISBN 978-1-85278-155-2. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, J. Management of Urban Regeneration and Conservation in China: A Case of Shanghai. In Dialogues in Urban and Regional Planning; Stiftel, B., Watson, V., Eds.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2005; pp. 126–156. ISBN 978-0-415-34693-1. [Google Scholar]

- Chakrabarty, D. Provincializing Europe: Postcolonial Thought and Historical Difference; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 2000; ISBN 978-1-4008-2865-4. [Google Scholar]

- Robinson, J. Ordinary Cities: Between Modernity and Development; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2006; ISBN 978-1-134-40695-1. [Google Scholar]

- Slater, T.R. Conserving Europe’s Historic Towns: Character, Managerialism and Representation. Built Environ. 1978 1997, 23, 144–155. [Google Scholar]

- Irsheid, C. The Protection of Cultural Property in the Arab World. Int. J. Cult. Prop. 1997, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, M. Built Heritage Conservation Policy in Selected Places; Paper Prepared by the Research and Library Services Division: Hong Kong, China, 2008.

- Ashworth, G.J. Conservation as Preservation or as Heritage: Two Paradigms and Two Answers. Built Environ. 1978 1997, 23, 92–102. [Google Scholar]

- Loulanski, T. Revising the Concept for Cultural Heritage: The Argument for a Functional Approach. Int. J. Cult. Prop. 2006, 13, 207–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, K. From Regulation to Participation: Cultural heritage, sustainable development and citizenship. In Forward Planning: The Function of Cultural Heritage in a Changing Europe; Council of Europe: Strasbourg, France, 2001; pp. 103–110. [Google Scholar]

- Costonis, J.J. Icons and Aliens: Law, Aesthetics, and Environmental Change; University of Illinois Press: Champaign, IL, USA, 1989; ISBN 978-0-252-01553-3. [Google Scholar]

- Talen, E. New Urbanism and American Planning: The Conflict of Cultures; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2005; ISBN 978-1-135-99261-3. [Google Scholar]

- Young, C.; Light, D. Communist heritage tourism: Between economic development and European integration. In Heritage and Media in Europe—Contributing towards Integration and Regional Development; Hassenpflug, D., Kolbmüller, B., Schröder-Esch, S., Eds.; Bauhaus-Universität Weimar: Weimar, Germany, 2006; pp. 249–261. [Google Scholar]

- Baldersheim, H.; Wollmann, H. An Assessment of the Field of Comparative Local Government Studies and a Future Research Agenda. In The Comparative Study of Local Government and Politics: Overview and Synthesis; Baldersheim, H., Wollmann, H., Eds.; IPSA’s World of Political Science; Barbara Budrich Publishers: Oplanden/Framington Hills, MI, USA, 2006; ISBN 978-3-86649-034-5. [Google Scholar]

- While, A. Modernism vs Urban Renaissance: Negotiating Post-war Heritage in English City Centres. Urban Stud. 2006, 43, 2399–2419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shiba, H. Comparative Local Governance: Lessons from New Zeland for Japan. Ph.D. Thesis, Victoria University of Wellington, Wellington, New Zealand, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Lidström, A. The comparative study of local government systems—A research agenda. J. Comp. Policy Anal. Res. Pract. 1998, 1, 97–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sellers, J.M. Between National State and Local Society: Infrastructures of Local Governance in Developed Democracies; Working Paper; Department of political science, University of Southern California: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Van de Walle, S.; Baker, K.; Skelcher, C. Citizen Support for Increasing the Responsibilities of Local Government in European Countries: A Comparative Analysis; Working Paper; University of Birmingham: Birmingham, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Stoker, G. The Comparative Study of Local Governance: The need to go global. Paper Presented at the Hallsworth Conference, University of Manchester, Manchester, UK, 17–18 March 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Lovelady, A. Broadened Notions of Historic Preservation and the Role of Neighborhood Conservation Districts 24th Smith-Babcock-Williams Student Writing Competition Runner-Up. Urban Lawyer 2008, 40, 147–184. [Google Scholar]

- Hobson, E. Conservation and Planning: Changing Values in Policy and Practice; Spon Press: London, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Arratia, R.N. Legal Forms of Financing Urban Preservation in Mexico. In Legal Methods of Furthering Urban Preservation; Novenstern, H., Koren, G., Eds.; Paper Submitted to the 2001 Conference of the International Legal Committee of ICOMOS; Society for the Protection of Nature in Israel Publications: Mive Yisrael, Israel, 2001; pp. 73–84. [Google Scholar]

- Franzese, P.L. A Comparative Analysis of Downtown Revitalization Efforts in Three North Carolina Communities; University of North Carolina: Chapel Hill, NC, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Mullin, J.; Kotval, Z.; Balsas, C. Historic Preservation in Waterfront Communities in Portugal and the USA. Port. Stud. Rev. 2000, 13, 40–61. [Google Scholar]

- Roth, D.C. Wish You Were Here: A Cross-Cultural Analysis of Architectural Preservation, Reconstruction and the Contemporary Built Environment. Syracuse J. Int. Law Commer. 2003, 30, 395–420. [Google Scholar]

- Tweed, C.; Sutherland, M. Built cultural heritage and sustainable urban development. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2007, 83, 62–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Rosa, F.; Di Palma, M. Historic Urban Landscape Approach and Port Cities Regeneration: Naples between Identity and Outlook. Sustainability 2013, 5, 4268–4287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Örücü, E. The Enigma of Comparative Law: Variations on a Theme for the Twenty-First Century; Martinus Nijhoff Publishers: Leiden, The Netherlands; Boston, MA, USA, 2004; ISBN 978-94-017-5596-2. [Google Scholar]

- Zweigert, K.; Kötz, H. An Introduction to Comparative Law, 3rd ed.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK; New York, NY, USA, 1998; ISBN 978-0-19-826859-8. [Google Scholar]

- Adie, B.A.; Hall, C.M. Who visits World Heritage? A comparative analysis of three cultural sites. J. Herit. Tour. 2017, 12, 67–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aggarwal, M.; Suklabaidya, P. Role of Public Sector and Public Private Partnership in Heritage Management: A Comparative Study of Safdarjung Tomb and Humayun Tomb. Int. J. Hosp. Tour. Syst. 2017, 10. [Google Scholar]

- Akagawa, N.; Sirisrisak, T. Cultural Landscapes in Asia and the Pacific: Implications of the World Heritage Convention. Int. J. Herit. Stud. 2008, 14, 176–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baarveld, M.; Smit, M.; Dewulf, G. Implementing joint ambitions for redevelopment involving cultural heritage: A comparative case study of cooperation strategies. Int. Plan. Stud. 2018, 23, 101–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balsas, C.J.L. Gaming anyone? A comparative study of recent urban development trends in Las Vegas and Macau. Cities 2013, 31, 298–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bamert, M.; Ströbele, M.; Buchecker, M. Ramshackle farmhouses, useless old stables, or irreplaceable cultural heritage? Local inhabitants’ perspectives on future uses of the Walser built heritage. Land Use Policy 2016, 55, 121–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barthel, D.L. Historic Preservation: Collective Memory and Historical Identity; Rutgers University Press: New Brunswick, NJ, USA, 1996; ISBN 978-0-8135-2293-7. [Google Scholar]

- Black, H.; Wall, G. Global-Local Inter-relationships in UNESCO World Heritage Sites. In Interconnected Worlds: Tourism in Southeast Asia; Ho, K.C., Ed.; Routledge: London, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2001; ISBN 978-1-136-39479-9. [Google Scholar]

- Boer, B.; Wiffen, G. Heritage Law in Australia; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Boussaa, D. Urban Conservation and Sustainability; Cases from Historic Cities in the Gulf and North Africa. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Technology & Sustainability in the Built Environment, King Saud University, Al-Riyadh, Saudi Arabia, 3–6 January 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Bronski, M.B.; Gabby, B.A. A Comparison of Principles in Several Architectural Conservation Standards. In The Use and Need for Preservation Standards in Architectural Conservation; Sickels-Taves, L.B., Ed.; American Society for Testing and Materials: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 1999; pp. 12–23. [Google Scholar]

- Brooks, E.; Law, A.; Huang, L. A comparative analysis of retrofitting historic buildings for energy efficiency in the UK and China. DisP Plan. Rev. 2014, 50, 66–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castillo, A.; Menéndez, S. Managing Urban Archaeological Heritage: Latin American Case Studies. Int. J. Cult. Prop. 2014, 21, 55–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corsane, G.; Davis, P.; Elliott, S.; Maggi, M.; Murtas, D.; Rogers, S. Ecomuseum Evaluation: Experiences in Piemonte and Liguria, Italy. Int. J. Herit. Stud. 2007, 13, 101–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cullingworth, B.; Nadin, V. Town and Country Planning in the UK, 14th ed.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA; London, UK, 2006; ISBN 978-1-134-24609-0. [Google Scholar]

- Cullingworth, B.; Nadin, V.; Hart, T.; Davoudi, S.; Pendlebury, J.; Vigar, G.; Webb, D.; Townshend, T. Town and Country Planning in the UK, 15th ed.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA; London, UK, 2014; ISBN 978-1-317-58564-0. [Google Scholar]

- Curry, K.E. Historic Districts: A Look at the Mechanics in Kentucky and a Comparative Study of State Enabling Legislation Special Feature: Land Use and Preservation. J. Nat. Resour. Environ. Law 1995, 11, 229–280. [Google Scholar]

- Dann, N.; Steel, M. The Conservation of Historic Buildings in Britain and the Netherlands: A Comparative Study. Struct. Surv. 1999, 17, 227–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Boer, S. Diffusion or Diversity in Cultural Heritage Preservation? Comparing Policy Arrangements in Norway, Arizona and the Netherlands. In Institutional Dynamics in Environmental Governance; Arts, B., Leroy, P., Eds.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2006; pp. 161–181. ISBN 978-1-4020-5078-7. [Google Scholar]

- De Boer, S. Traces of Change: Dynamics in Cultural Heritage Preservation Arrangements in Norway, Arizona and The Netherlands. Ph.D. Thesis, Radboud University, Nijmegen, The Netherlands, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Donaghey, S. What is Aught, but as ’tis Valued? An analysis of strategies for the assessment of cultural heritage significance in New Zealand. Int. J. Herit. Stud. 2001, 7, 365–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Approaches to the Governance of Historical Heritage over Time: A Comparative Report; Fisch, S., Ed.; Cahier D’histoire de L’administration; IOS Press: Amsterdam, The Netherlands; Fairfax, VA, USA, 2008; ISBN 978-1-58603-853-3. [Google Scholar]

- Grazer-Bideau, F.; Kilani, M. Multiculturalism, cosmopolitanism, and making heritage in Malaysia: A view from the historic cities of the Straits of Malacca. Int. J. Herit. Stud. 2012, 18, 605–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grenville, J. Conservation as Psychology: Ontological Security and the Built Environment. Int. J. Herit. Stud. 2007, 13, 447–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guarneros-Meza, V. Local Governance in Mexico: The Cases of Two Historic-centre Partnerships. Urban Stud. 2008, 45, 1011–1035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gullino, P.; Larcher, F. Integrity in UNESCO World Heritage Sites. A comparative study for rural landscapes. J. Cult. Herit. 2013, 14, 389–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holtorf, C. What Does Not Move Any Hearts—Why Should It Be Saved? The Denkmalpflegediskussion in Germany. Int. J. Cult. Prop. 2007, 14, 33–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khirfan, L. Traces on the palimpsest: Heritage and the urban forms of Athens and Alexandria. Cities 2010, 27, 315–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khirfan, L. World Heritage, Urban Design and Tourism: Three Cities in the Middle East; Ashgate: Farnham, UK, 2014; ISBN 978-1-4094-2408-6. [Google Scholar]

- King, V.T.; Hitchcock, M. UNESCO World Heritage Sites in Southeast Asia: Problems and Prospect. In Rethinking Asian Tourism: Culture, Encounters and Local Response; Porananond, P., King, V.T., Eds.; Cambridge Scholars Publishing: Newcastle-Upon-Tyne, UK, 2014; pp. 24–70. ISBN 978-1-4438-6972-0. [Google Scholar]

- Klamer, A.; Mignosa, A.; Petrova, L. Cultural Heritage Policies: A comparative perspective. In Handbook on the Economics of Cultural Heritage; Rizzo, I., Mignosa, A., Eds.; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 2013; pp. 37–88. ISBN 978-0-85793-100-9. [Google Scholar]

- Kovacs, J.F.; Jonas Galvin, K.; Shipley, R. Assessing the success of Heritage Conservation Districts: Insights from Ontario, Canada. Cities 2015, 45, 123–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landorf, C. A Framework for Sustainable Heritage Management: A Study of UK Industrial Heritage Sites. Int. J. Herit. Stud. 2009, 15, 494–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Last, K.V.; Shelbourn, C. Caring for Places of Worship? An Analysis of Controls over Listed Buildings in England and Scotland. Art Antiq. Law 2001, 6, 111–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.L. Urban conservation policy and the preservation of historical and cultural heritage. Cities 1996, 13, 399–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, F.; du Cross, H. A comparative analysis of three heritage management approaches in Southern China: Guangzhou, Hong Kong, and Macau. In Asian Heritage Management: Contexts, Concerns, and Prospects; Sila, K.D., Chapagain, N.K., Eds.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA; London, UK, 2013; pp. 105–121. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y. Heritage Tourism: The Contradictions between Conservation and Change. Tour. Hosp. Res. 2003, 4, 247–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linantud, J.L. War Memorials and Memories: Comparing the Philippines and South Korea. Int. J. Herit. Stud. 2008, 14, 347–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Losson, P. The inscription of Qhapaq Ñan on UNESCO’s World Heritage List: A comparative perspective from the daily press in six Latin American countries. Int. J. Herit. Stud. 2017, 23, 521–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lunn, K. War Memorialisation and Public Heritage in Southeast Asia: Some Case Studies and Comparative Reflections. Int. J. Herit. Stud. 2007, 13, 81–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meskell, L.; Liuzza, C.; Brown, N. World Heritage Regionalism: UNESCO from Europe to Asia. Int. J. Cult. Prop. 2015, 22, 437–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mısırlısoy, D.; Günçe, K. Adaptive reuse strategies for heritage buildings: A holistic approach. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2016, 26, 91–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miura, K. World Heritage Sites in Souteast Asia: Angkor and Beyond. In Heritage Tourism in Southeast Asia; Hitchcock, M., King, V.T., Parnwell, M., Eds.; NIAS Press: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2010; ISBN 978-87-7694-059-1. [Google Scholar]

- Mualam, N. Conflict over Preservation of the Built Heritage: A Cross-National Comparative Analysis of the Decisions of Planning Tribunals. Ph.D. Thesis, Technion, Israel Institute of Technology, Haifa, Israel, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Mualam, N.Y. New Trajectories in Historic Preservation: The Rise of Built-Heritage Protection in Israel. J. Urban Aff. 2015, 37, 620–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Negussie, E. Implications of Neo-liberalism for Built Heritage Management: Institutional and Ownership Structures in Ireland and Sweden. Urban Stud. 2006, 43, 1803–1824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, M.-K. Tales from Two Chinese Cities: The Dragon’s Awakening to Conservation in face of Growth? Plan. Theory Pract. 2009, 10, 267–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nyseth, T.; Sognnæs, J. Preservation of old towns in Norway: Heritage discourses, community processes and the new cultural economy. Cities 2013, 31, 69–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ornelas, C.; Guedes, J.M.; Breda-Vázquez, I. Cultural built heritage and intervention criteria: A systematic analysis of building codes and legislation of Southern European countries. J. Cult. Herit. 2016, 20, 725–732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Construction of Built Heritage: A North European Perspective on Policies, Practices and Outcomes; Phelps, A., Ashworth, G.J., Johansson, B.O.H., Eds.; Ashgate: Burlington, UK, 2002; ISBN 978-0-7546-1846-1. [Google Scholar]

- Pickard, R. A Comparative Review of Policy for the Protection of the Architectural Heritage of Europe. Int. J. Herit. Stud. 2002, 8, 349–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pickard, R. Area-Based Protection Mechanisms for Heritage Conservation: A European Comparison. J. Archit. Conserv. 2002, 8, 69–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poor, J.; Snowball, J. The valuation of campus built heritage from the student perspective: Comparative analysis of Rhodes University in South Africa and St. Mary’s College of Maryland in the United States. J. Cult. Herit. 2010, 11, 145–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quintard-Morenas, F. Preservation of Historic Properties’ Environs: American and French Approaches. Urban Lawyer 2004, 36, 137–190. [Google Scholar]

- Rautenberg, M. Industrial heritage, regeneration of cities and public policies in the 1990s: Elements of a French/British comparison. Int. J. Herit. Stud. 2012, 18, 513–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reeves, R.M. A Comparative Analysis of Southern Nevada Municipalities, and Their Active Participation to Implement Historical Preservation. Master’s Thesis, University of Nevada, Las Vegas, NV, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Ren, W.; Han, F. Indicators for Assessing the Sustainability of Built Heritage Attractions: An Anglo-Chinese Study. Sustainability 2018, 10, 2504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryberg-Webster, S.; Kinahan, K.L. Historic preservation in declining city neighbourhoods: Analysing rehabilitation tax credit investments in six US cities. Urban Stud. 2017, 54, 1673–1691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryberg-Webster, S. Preserving Downtown America: Federal Rehabilitation Tax Credits and the Transformation of U.S. Cities. J. Am. Plan. Assoc. 2013, 79, 266–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sande, A. Mixed world heritage in Scandinavian countries. Int. J. Herit. Stud. 2015, 21, 791–804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seduikyte, L.; Grazuleviciute-Vileniske, I.; Kvasova, O.; Strasinskaite, E. Knowledge transfer in sustainable management of heritage buildings. Case of Lithuania and Cyprus. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2018, 40, 66–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shelbourn, C. Legal Protection of the Cherished and Familiar Local Scene in the USA and the UK Through Historic Districts and Conservation Areas—Do the Legislators Get What They Intended? In Proceedings of the Forum UNESCO University and Heritage 10th International Seminar, Newcastle-upon-Tyne, UK, 11–16 April 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Shipley, R.; Reyburn, K. Lost Heritage: A survey of historic building demolitions in Ontario, Canada. Int. J. Herit. Stud. 2003, 9, 151–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shipley, R.; Snyder, M. The role of heritage conservation districts in achieving community economic development goals. Int. J. Herit. Stud. 2013, 19, 304–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simpson, F.; Chapman, M. Comparison of urban governance and planning policy: East looking West. Cities 1999, 16, 353–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soane, J.V.N. Agreeing to Differ? English and German conservation practices as alternative models for European notions of the built past. Int. J. Herit. Stud. 2002, 8, 267–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solomon-Maman, V. Historic Preservation According to the Building and Planning Law: An International Comparison. Master’s Thesis, Technion, Israel Institute of Technology, Haifa, Israel, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Strasser, P. “Putting Reform Into Action”—Thirty Years of the World Heritage Convention: How to Reform a Convention without Changing Its Regulations. Int. J. Cult. Prop. 2002, 11, 215–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, T.; Landorf, C. Subject–object perceptions of heritage: A framework for the study of contrasting railway heritage regeneration strategies. Int. J. Herit. Stud. 2015, 21, 1050–1067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Oers, R. Towards new international guidelines for the conservation of historic urban landscapes (HUL)s. City Time 2007, 3, 43–51. [Google Scholar]

- Veldpaus, L.; Roders, A.P. Learning from a Legacy: Venice to Valletta. Chang. Time 2014, 4, 244–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vigneron, S. From local to World Heritage: A comparative analysis. Hist. Environ. Policy Pract. 2016, 7, 115–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, Y.W.; Lee, V.P.Y. Postcolonial cultural governance: A study of heritage management in post-1997 Hong Kong. Int. J. Herit. Stud. 2017, 23, 275–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.-J.; Lee, H.-Y. How government-funded projects have revitalized historic streetscapes—Two cases in Taiwan. Cities 2008, 25, 197–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G. Voices in Cultural Heritage Preservation: A Comparative Study between New Orleans and Changting (China). Master’s Thesis, Louisiana State University, Baton Rouge, LA, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Ween, G.B. World Heritage and Indigenous rights: Norwegian examples. Int. J. Herit. Stud. 2012, 18, 257–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitehand, J.W.R.; Gu, K.; Whitehand, S.M.; Zhang, J. Urban morphology and conservation in China. Cities 2011, 28, 171–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, K. Comparative Analysis of Policies of Architectural Heritage Conservation in East Asian and European Countries: Legislation, Administration and Finance. Ph.D. Thesis, Technische Universität Dresden, Dresden, Germany, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, C.-Y. Cultural Resilience in Asia: A Comparative Study of Heritage Conservation in Lijiang and Bagan. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Washington, Seattle, WA, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Yung, E.H.K.; Chan, E.H.W. Problem issues of public participation in built-heritage conservation: Two controversial cases in Hong Kong. Habitat Int. 2011, 35, 457–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yung, E.H.K.; Langston, C.; Chan, E.H.W. Adaptive reuse of traditional Chinese shophouses in government-led urban renewal projects in Hong Kong. Cities 2014, 39, 87–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Wu, Z. The reproduction of heritage in a Chinese village: Whose heritage, whose pasts? Int. J. Herit. Stud. 2016, 22, 228–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Benefits | Limitations/ Challenges | |

|---|---|---|

| The ‘N’ question | ||

| Small N | Fewer resources needed; comparable elements can be identified more easily; similarities and differences can be highlighted; can help discuss thoroughly specific challenges and issues that relate to built heritage. | Limited contexts; less generalizable; risks being too narrow in its comparative scope. May result in telling endless little tales about heritage while the reader is left with little idea of how individual cases relate to other situations. |

| Large N | Generalizable; overarching; broad comparisons that can encourage transfer of knowledge between the compared jurisdictions; by encouraging a high degree of abstraction, comparison can highlight select issues that relate to the built heritage. | Time-consuming; needs resources to conduct an overarching comparison; can lead to abstraction and leapfrog over nuances. Many variables influence built heritage, by increasing the number of compared cases, differences can become overwhelming and it might be harder to pinpoint similarities. |

| Scope of comparison | ||

| Cross-national | Provides an overarching framework for understanding the built heritage; focuses on general rules and practices that affect local conditions. | Built heritage is often practiced at the local level; local policies and practices are overlooked while conducting inquiries that focus on the national scale. |

| Cross-local | Can focus on nuance and conduct a thorough and rich analysis of local conditions. | Harder to generalize from; local and insular analysis which often compares localities in one jurisdiction may not provide a sufficiently broad perspective; might leapfrog over different national-level institutional contexts that affect built heritage |

| Cross-local/cross-national | Scaling down the comparison is important when looking at the built heritage that is often defined and protected locally; Cross-local and cross-national, enable practitioners to learn from other contexts while still maintaining a local focus. | Mandates familiarity with both national and local scales, which–in turn–may delimit the number of compared cases (i.e., small ‘N’). |

| Geographic coverage | ||

| Focused/limited coverage | Can encourage cross-border transfer of knowledge and experience pertaining to built heritage. | Runs the risk of becoming less relevant to other contexts; isolated comparisons; emphasizing a set of shared heritage values, principles, settings and beliefs. In built heritage studies, limited coverage might also end up as a highly Euro-centric analysis. |

| Expansive | Goes beyond cross-border analysis; extensive geographical coverage can entice mutual learning in different settings; contribute towards the universalization of knowledge pertaining to built heritage and to sustainable global heritage practices. | Challenging to conduct; subject to resource limitations; mandates familiarity with different settings. |

| Type of comparison | ||

| Structured | Generalizable; systematic; findings are organized in an orderly fashion, thus more easily transferable to policy; facilitates the compartmentalization of knowledge. | Runs the risk of not paying sufficient attention to small details and nuances; thus, socio-cultural context and meanings of built heritage might be overlooked. |

| Unstructured | Collecting data about several jurisdictions and themes; their value is in developing, putting forward and flagging issues and/or challenges associated with built heritage. | Loosely comparative and do not necessarily provide an integrated analysis of policy, nor overarching observations about built heritage. |

| Semi-structured | Focuses on specific comparable elements, while avoiding a rigorous and comprehensive comparative analysis. | Relatively structured, but does not provide a thorough comparison that runs throughout the analysis. |

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Mualam, N.; Barak, N. Evaluating Comparative Research: Mapping and Assessing Current Trends in Built Heritage Studies. Sustainability 2019, 11, 677. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11030677

Mualam N, Barak N. Evaluating Comparative Research: Mapping and Assessing Current Trends in Built Heritage Studies. Sustainability. 2019; 11(3):677. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11030677

Chicago/Turabian StyleMualam, Nir, and Nir Barak. 2019. "Evaluating Comparative Research: Mapping and Assessing Current Trends in Built Heritage Studies" Sustainability 11, no. 3: 677. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11030677

APA StyleMualam, N., & Barak, N. (2019). Evaluating Comparative Research: Mapping and Assessing Current Trends in Built Heritage Studies. Sustainability, 11(3), 677. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11030677