Abstract

Transcending the conventional debate around efficiency in sustainable consumption, anti-consumption patterns leading to decreased levels of material consumption have been gaining importance. Change agents are crucial for the promotion of such patterns, so there may be lessons for governance interventions that can be learnt from the every-day experiences of those who actively implement and promote sustainability in the field of anti-consumption. Eighteen social innovation pioneers, who engage in and diffuse practices of voluntary simplicity and collaborative consumption as sustainable options of anti-consumption share their knowledge and personal insights in expert interviews for this research. Our qualitative content analysis reveals drivers, barriers, and governance strategies to strengthen anti-consumption patterns, which are negotiated between the market, the state, and civil society. Recommendations derived from the interviews concern entrepreneurship, municipal infrastructures in support of local grassroots projects, regulative policy measures, more positive communication to strengthen the visibility of initiatives and emphasize individual benefits, establishing a sense of community, anti-consumer activism, and education. We argue for complementary action between top-down strategies, bottom-up initiatives, corporate activities, and consumer behavior. The results are valuable to researchers, activists, marketers, and policymakers who seek to enhance their understanding of materially reduced consumption patterns based on the real-life experiences of active pioneers in the field.

1. Introduction

Considering the urgent global challenge to mitigate climate change, save natural resources, and achieve the sustainability goals set in the Agenda 2030 [1], overcoming the current unsustainable patterns of overconsumption is a wicked problem that requires innovation beyond launching more efficient technologies [2,3]. Social innovations which reduce the quantitative level of material consumption in affluent societies have the potential for social transformation towards sustainable development [4]. They have begun to draw the attention of researchers, activists, and policymakers alike.

This article focuses on social innovations which enable and motivate citizens to quantitatively reduce their consumption. Social innovation is a term widely applied to new developments in practices, often across sectors, which aim at improving social inclusion, quality of life, and well-being [5,6,7,8,9]. Based on the theory of social practice [10], we understand social innovations as activities which develop from the bottom-up through civil-society led initiatives. They introduce and enhance creative re-thinking and re-organization of the way we live through establishing social practices of sustainable consumption which diverge from mainstream routines [11]. Consumers themselves act as agents of change by intentionally initiating and disseminating alternative practices in their social networks as grassroots social innovations [12,13]. Social innovations provide opportunities in experimental niches and stabilization of practices that might diffuse into households and wider social networks, according to sustainable transition theory [14]. They can be improved and accelerated by targeted policies [15].

Social innovations for sustainable consumption include a wide range of activities: Do-It-Together Practices (e.g., food and energy cooperatives), strategic consumption through Carrot Mobs or Living Labs, sharing communities (e.g., Foodsharing or neighborhood networks for sharing and swapping), Do-It-Yourself (e.g., upcycling workshops or repair cafés), and utility enhancing consumption including rental or second hand shops [11]. Most of these activities focus on consuming better. In our exploratory study, we shift the focus towards two practices of sustainable anti-consumption, which embody the conscious decision not to consume a product at all.

Anti-consumption practices potentially challenge the problem of over-consumption in affluent societies and offer a valuable subject for transformative science [16]. Anti-consumption scholars focus on the reasons against consumption by studying the conscious and deliberate rejection, avoidance, reclaiming, and reduction of products, brands, and commercial transactions [17,18]. Anti-consumption potentially decreases waste and natural resource use [19], and leads to lower ecological pressure [20,21]. Well-being and anti-consumption are positively associated [22], although enforced reduction of consumption shows rather negative effects on personal satisfaction and happiness [23]. A variety of materially reduced consumer behavior patterns are studied in relation to anti-consumption. Our research focuses on collaborative consumption and voluntary simplicity, which represent the conscious decision around “whether or not a product should even be purchased” [24] (p. 183). Seegebarth et al. [25] show that voluntary simplicity and collaborative consumption as anti-consumption practices are rooted in sustainability.

Motivated by universalistic values [26], voluntary simplifiers seek life satisfaction through reduced levels of material consumption [27,28,29,30]. They are less likely to have personal debts compared to consumers with more materialistic concerns [31]. Voluntary simplicity incorporates the idea of not consuming more than is necessary for satisfying human needs, conceptualized as voluntary sufficiency [15,32,33]. Consumers practicing simplistic lifestyles report that activities of collaborative consumption support their lifestyles [33]. Collaborative consumption refers to non-ownership-based access to products through sharing, borrowing, swapping, or renting within social communities or commercial settings [34,35]. Motivational reasons are the benefits of socializing, saving on personal costs, and protecting environmental resources [36,37,38]. On the one hand, collaborative consumption patterns are suspected to fuel additional consumption because consumers can now afford to use goods as services without investing money into purchasing and maintaining them. As the sharing economy develops, growing and professionalizing sharing platforms put more emphasis on consumption than sustainability in their public communication [38]. On the other hand, sharing goods increases the intensity of use and potentially substitutes private ownership of rarely used goods, which contributes to a more efficient use, prolonging of product life spans, and ultimately saving resources. Collaborative consumption refers to private routines (e.g., peer-sharing between neighbors), local sharing initiatives (e.g., food sharing networks), and also commercial offers (e.g., Airbnb).

In the following, rather than focusing on the practice of anti-consumption as a social innovation itself, we focus on means of governance that can stimulate its emergence and dispersion. We aim to offer a practice- and needs-oriented understanding of governance to find out how practices of anti-consumption can be further enabled and encouraged. Research on governance is most prominently conducted in business and economic contexts, political sciences, and organizational research, with a focus on social innovations in the context of social entrepreneurship [39,40], citizen movements [41,42,43], and welfare services [44,45]. Social innovations are often perceived to occur as consequences of failures in governance and politics [4]. Implications for governance are diverse in social innovation research. Pol and Ville [5] call for governmental support of social innovations that have no motive for profit and address needs that cannot be satisfied through market mechanisms. Borzaga and Bodini [46], despite preferring economically self-dependent social enterprises, more specifically suggest “measures such as supporting experimentation and emersion of new ideas through awards and other monetary incentives, and supporting existing initiatives through subsidies (such as grants and tax breaks) and contracting out policies” (p.12) for non-profit social innovations providing a public good. Other approaches emphasize self-governance among individuals and communities that gain autonomy through knowledge creation and empowerment, thereby unlocking the transformative potential of social innovations [4]. In sustainable innovation, three perspectives on primary governance actors traditionally occur: state-centric, corporate-centric, and society-centric [47]. Lupova-Henry and Dotti [48] observe a trend towards concerted action between state-, market-, and network-centric actors based on cooperation, trust-building efforts, knowledge exchange, and an understanding of the environment as a ‘common’ good.

Despite an emphasis on providing tools to support social innovations that focus on sustainable energy transition, social and economic progress [49,50,51], a specific focus on governing social innovation for sustainable anti-consumption is rare. In a literature review, Grabs et al. [13] collected success factors for grassroots initiatives which collectively go beyond the consumption choice for a greener product and include voluntary simplicity. On the individual level, these success factors include personal motivation and a belief that change is possible [52]. While individual values and beliefs impact an individuals’ ability to be an anti-consumer, studies highlight a shift from individual actions to a collective movement. Particularly in collaborative consumption, sharing communities should project a value-neutral image to invite diverse groups of participants [53]. Sharing attracts various expectations—while some participants seek a sense of community in trust-based groups, others are more purely transaction-oriented [54]. On an interpersonal level, the social influence of and support by others are highlighted for voluntary simplicity [55,56]. For a collective movement, supportive sociocultural and institutional factors are necessary [12,33,57], for instance through providing space for experimentation [11]. Pedagogical processes and knowledge exchange allow the acquisition of competencies among consumers, initiators, and participants [11,32]. Furthermore, communicative action supports the acceptance and adoption of alternative sustainable behavior [11,33]. Leadership, organizational structure, and strategies to facilitate cooperation and resources of initiatives matter on the group level [12,58]. A tendency to become more commercially oriented over time among niche grassroots organizations in collaborative consumption may benefit the diffusion of the social innovation, but threaten the organizations’ internal legitimacy [59]. Frenken and Schor [60] advocate user-governed sharing platforms, because policy regulations often failed in protecting traditional markets from negative disruption by profit-oriented sharing economy corporations (in e.g., housing and mobility). On the societal level, partnerships with external actors to gain political support and favorable infrastructures help. Recommendations for governance in anti-consumption social innovations address local authorities, educators, and policy makers. Governance through an alignment of non-state and governmental activities has been identified as necessary [57].

To value the aim of practice-oriented sustainability transition research and to further explore a broad range and interrelations of public policy and private interventions, we conducted a qualitative study asking practitioners and experts in voluntary simplicity and collaborative consumption to share their experiences and thoughts on good governance for the social innovations they are engaged in. To the best of our knowledge, existing research on governance and social innovations for sustainability has not yet explicitly emphasized these two patterns of anti-consumption lifestyles based on explorative expert interviews. To contribute to this research field, our research question is: What lessons for governance interventions can be learnt from the every-day experiences of those who actively implement and promote sustainability in anti-consumption? We specifically look at governance interventions that support individual and group initiatives in their aim to engage more people in voluntary simplicity and collaborative consumption practices.

The contribution of this article is to provide insiders’ perspectives on social innovation governance, to identify potential points of action, and to highlight future research directions. The results represent the experiences of social innovation practitioners and experts from diverse backgrounds, whose voices are often neglected in academic research. The results were derived within a project funded by the German Federal Ministry of Education and Research.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data Collection

Considering the valuable but rare existing insights into sustainable social innovations which support the decision not to consume, we decided to apply an exploratory qualitative approach by conducting expert interviews. As initiatives in strong sustainable consumption, including voluntary simplicity and collaborative consumption, are mostly “initiated and driven by individual change agents” [13] (p.12), we turned to the expertise of those individuals. Looking for the “hidden knowledge” of practitioners and specialists in the field, we had no specific a priori expectations in terms of research findings and used a semi-structured interview guideline [61]. Using an open format with rather general questions allowed us to remain flexible to the interviewees’ input and to derive the aspects of governance that were most salient in the experts’ minds and everyday experiences [62]. The semi-structured interview guideline included the following questions concerning governance:

- What are the foundations to succeed for your initiative?

- What are potential barriers for your initiative?

- How can a common consciousness for the consumption pattern your initiative represents be increased?

The interviews were conducted either face-to-face (13 interviews), via video call (3 interviews), or phone call (1 interview) from May to July 2015. They lasted 45 min on average and all records were transcribed verbatim. We systematically examined the interview data through a qualitative content analysis [62] using the software MAXQDA 12. Qualitative content analysis aims to consider all material, but systematically reduce it to the essential information [63]. A preceding literature review on the topic determined the application of three a priori deductive categories according to the state-corporate-society centric trichotomy in governance on sustainable innovation: top-down policies, entrepreneurship, and bottom-up activities (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Initial deductive coding categories.

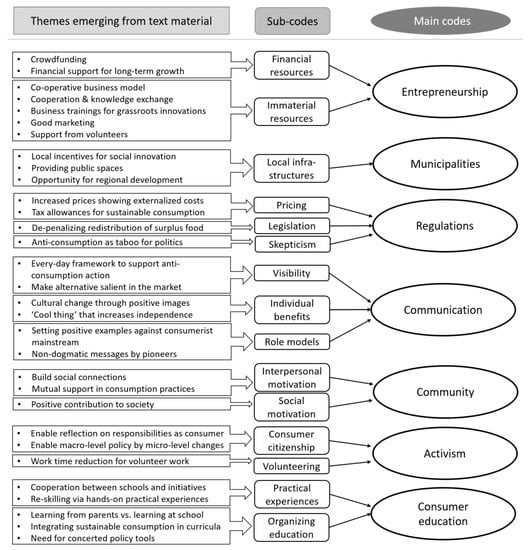

Two researchers independently read and coded the text material, then continuously compared their results for themes and categories emerging from the data. Discussing the coding process lead to the inductive revision and extension of the coding scheme. We agreed on a coding frame of seven interrelated main codes (see Figure 2 for an extensive illustration of the data structure). The two coders then repeated the individual coding and compared and discussed all material until a final agreement was reached [64].

Figure 2.

Final data structure.

2.2. Expert Sample

Table 1 displays the successively chosen and vast yet interrelated sample, which consists of spokespersons and initiators of grassroots projects, entrepreneurs, consultants, bloggers, activists, and one scientist from Germany. The first interviewees were contacted after an online search for initiatives and activists who publicly aim to reach an audience for collaborative consumption or voluntary simplicity activities. Afterwards, we also applied snowball sampling by asking interviewees to recommend other potential participants. All contacted persons agreed to participate. We achieved sufficient content saturation with regards to no new themes surfacing at a total of 17 interviews [65]. All interviewees were assigned a pseudonym to maintain their anonymity.

Table 1.

Interviewees’ expertise and professional background.

All interviewed experts share the aim of engaging a greater audience in activities of anti-consumption to strengthen sustainability. The majority engages in non-commercial activities. Although all seek a public platform for their cause, they can still be identified as positioned within a societal niche [59,66].

Nine interviewees (two of them paired) provided special expertise in voluntary simplicity. Christina is a sustainability activist who chose a lifestyle of voluntary simplicity by living with no money at all, and she shares her experiences with others as an activist in a local community center. Alexander is a committed voluntary simplifier who aims to inspire through blogging on minimalism, hiking, and veganism. Martina is a campaigner for the project “One Year without Stuff”, a social experiment motivating participants to avoid buying new items for a year. Helena and Sven coach audiences on sustainable lifestyles of voluntary simplicity. Jane is an author and campaigner who publicized her personal experiences after being abstinent from shopping for clothes for a year. Valerie is deeply engaged with one cultural center for creative recycling of used material, and another for regionally focused lifestyles of sufficiency. Dominic launched an online community for sustainable consumption and is a researcher on the topic. Researcher Amelie, who conducts different studies on people’s lifestyles of sufficiency, allows insights into the status of simplicity in consumers’ everyday lives and opportunities for its promotion.

Three collaborative consumption initiatives in the sample classify as commercial entrepreneurship models with a social and environmental benefit. Naomi founded a company for renting premium-quality fashion and jewelry to individuals. Paul represents a co-operatively organized online shopping platform for peer-shared and sustainable goods. Vincent initiated a social start-up that offers renting practical goods for an hourly fee. The goods can be accessed via a smartphone app in automatized boxes in public spaces.

Four sharing initiatives take place in a non-commercial setting. Robert is the manager of a local peer-to-peer lending shop, where individual members can exchange their private goods free of charge. Vasili, who is active in a neighborhood initiative connecting people within a community through activities with a social and environmental purpose, focuses on peer-to-peer sharing of goods. Ruben is an ambassador for the Foodsharing community, an international association whose volunteers collect and non-commercially redistribute surplus food from households, stores, and food producers. Caroline, a connector in an international network of collaborative consumption initiatives, shares her insights into the scene.

Introducing a meta-perspective on governance for social innovations, we included two experts on consumer education when this topic occurred as dominant in the interviews. Veronika is a consultant on consumer education focusing on sustainability in an agency for consumer rights. Dieter is a consumer educator with several decades of experience in the fields of sustainability and financial literacy.

3. Results

In the following, findings from the interviews are structured according to the final code system and illustrated by interviewees’ statements.

3.1. Entrepreneurship

Six interviewees discussed opportunities and barriers for entrepreneurship as a carrier of social innovation. Robert creates the comparison that “it is learning by doing for (our local peer-to-peer lending shop). As in every other company, you need good marketing, a business model, then you can be successful”. Vasili and Paul mentioned that their sharing initiatives heavily rely on the support of volunteers. Paul, Vincent, and Valerie see potential in cooperative (co-op) business models, which according to them could help to structure sustainable enterprises, to democratically control economic pressures to expand, and engage consumers in economically sustainable practices. Yet, Paul criticizes structural disadvantages as cooperative models are not applicable for many subvention funds and require strong commitment from their members, often more than private individuals are able to oblige. On the other hand, “crowdfunding was a positive experience for us. That is a part of a sharing economy to us, too, to share the business, the responsibility and the risks. Many people got to know us through crowdfunding, liked our idea, and supported us”. Like Valerie and Vincent, Caroline also discussed financial funds for sustainability-focused enterprises. According to her, “the state should support and invest in alternative projects which look at the core of sustainability in a long-term perspective, because economic survival is harder for them”. Robert, whose lending-shop is of one of those long-term projects, confesses “when we started, we just said ‘let’s do it.’ That is why companies with an actual business model are ahead of us. That is where we should get better”. His suggestion of business trainings targeting grassroots initiatives could help to professionalize efforts to create a more sustainable economy based on less material consumption. Furthermore, Vincent, Caroline, and Paul see a lack of collaboration and knowledge exchange between existing peer-sharing-initiatives, although these would help to prevent repeated errors by learning from other groups’ mistakes.

3.2. Municipalities

Five interviewees see various opportunities for municipalities to support and profit from social innovations. Dominic envisioned his hometown as a model town for sustainable, sufficient lifestyles, where food is grown on communal grounds and citizens exchange services and goods without depending on money. Christina emphasized the necessity of freely available public spaces which municipalities could provide: “You need places where you can just connect to each other, where this culture can thrive, where you are not alone (…) where you do not necessarily have to consume. Thinking big, remodeling public spaces, where consumption is not in the spotlight”. Vincent emphasized the commercial potential of local communities as sharing platforms for mobility and housing, so municipalities should be interested “in keeping the wealth through creating the sharing system themselves, instead of letting international corporations absorb profits”. “Municipalities actually look for sustainable strategies for their regional development programs” according to simplicity activist Valerie. Amelie supports the idea to strengthen the position of local municipalities in opposition to federal structures: “Municipalities relatively easily can create local incentive structures like repair workshops or sharing services (…) which is a lot easier on a smaller level, more accessible for people (…). Passing directives on a federal level is still too unsexy”.

3.3. Regulation

Top-down policy approaches received inconsistent evaluations in the interviews, spanning from rather specific ideas for regulation to a general unease with politics’ lethargy. Giving a rather specific suggestion, Dieter supported the idea of “a second price tag for the societal costs, which are normally not included in products (…) the costs which society pays elsewhere, with the aim to create a different consciousness for the effects of consumption”. Valerie advocates including increased energy prices in transport costs to strengthen consumption of regional goods. Foodsharing activist Ruben sees fewer constraining policies for distributing food beyond expiration dates, for instance in freely accessible food cabinets, as an accelerator for preventing food waste. Despite these ideas for regulation focused on specific domains of consumption, Ruben and Dieter express skepticism about politicians’ will to actually engage in policies for reduced consumption levels. Likewise, Amelie identifies a negative attitude towards sufficient consumption levels as a barrier for implementing policies on the subject. “Strategies for more sufficiency in consumption are usually not deliberated by politicians, because sufficiency is treated synonymously with abstinence, which is a knock-out criterion (…). Instead, I would put a focus on the micro level, the more open a society becomes towards sufficiency, it gets easier to implement policies like tax allowances for riding a bike to work instead of a car”. Jane expresses low expectations: “You can create your small better world, but on a larger level, I am still waiting for change”.

3.4. Communication for an Innovative Culture

3.4.1. Visibility of Initiatives

Many interviewees point out that individuals who are willing to change their consumption habits still need more visible infrastructures to actually practice simplicity and collaborative consumption. According to researcher Amelie, “opportunities to consume on a sufficient level actually just need to be more visible, to confront people, because people are not generally hesitant against sufficient living, they just don’t know how to act yet, because sufficiency is not a guiding principle”. Martina explains that her campaign ‘One Year without Stuff’ offers “a tool that helps people to put their desire to consume less into action” and “makes it easier, because you commit to your framework and you don’t have to decide every single time if you are going to buy something or not”. As Robert puts it: “It is so important to create alternatives, our project is like a model to show what can be done”. Online lending platform representative Vincent says that “it is not easy to visualize our alternative offer in the market, to reach people in the right moment”. Like him, other experts describe marketing techniques applied for their initiatives, like word-of-mouth advertising (Martina, Vincent, Naomi), personal contacts to participants (Paul), blogging (Naomi), or creating a brand (Vincent) to make alternative practices to the conventional market system more salient for consumers.

3.4.2. Addressing Individual Benefits

Four experts highlight different individual benefits of sustainable anti-consumption as the triggers to open up personal reflection, to create a positive framing, and to engage people in practices of anti-consumption as a viable option within a consumerist paradigm.

Amelie’s statement emphasizes an aspect of easiness: “Sufficient consumption should be seen as something normal, that makes life easier, it should not only be about reducing everything. Consuming causes responsibilities, for a car, for instance (…). Instead, sufficiency should be communicated as a ‘cool thing’, (…) as reduction of responsibility for your possessions which allows you to be more independent”. She adds that “economically, you gain financial opportunities and more free time by living in a more simplistic simpler (…) people can do so many things without having to consume, there are so many opportunities to use a tight budget well and be happy with that. That is a new reasoning, (…) to understand sufficiency as a strategy to just deal with everyday life”. Alexander desires a more positive depiction of simplifiers in public media: “if media presentations focus on environmental benefits, or that you gain financial liberties and more free time, by focusing on those advantages (…) then there is a more positive image and more people might get inspired”. Christina states that at the beginning of her experiment to live without money, she was confronted with the social perception that “if you want to have fun, you need money. The more money, the more fun. And money is associated with freedom. One could work on that, see how money and freedom and fun become less connected”. She warns that “if it is only about reducing, you can become stingy very easily, feel bad about yourself, and feel bad about all the stuff you do not have. Just having less and saving up, that is not the point, it’s about creating things yourself and being less passive”. Dominic even envisions a transformed consumer culture: “It needs that cultural change; that it is cool and chic not to own new stuff, but to wear vintage. That knowing how to repair stuff and not throwing it away is cool”.

3.4.3. Role Models

Simplicity pioneer Dominic critiqued an omnipresence of pressure to consume through advertising in public places. Martina proclaimed that “it all gets down to advertising, it unnecessarily pushes greed and social competition”. Adding to the problem, Jane observed that “YouTube stars promoting excessive consumption in ‘shopping hauls’ serve as role models” and that teenagers “often seek guidance to shape their characters, that is why they are easily influenced by advertising”. Dominic expressed the positive potential of role models in mass media: “Maybe we will also see some celebrities commit to a sustainable lifestyle, which would make sustainability more normal and a cool thing”. Anti-consumption practitioners quickly become role-models themselves, like Valerie: “the people around me now all see consumption in a different perspective”. Jane and Martina recalled how not taking themselves too seriously and remaining non-dogmatic about their anti-consumption practices caused others to respond positively to their practices. Accordingly, Christina noted about her experiences: “People responded positively towards my simpler lifestyle, probably because I was never dogmatic or judgmental about it”.

3.5. Community

While Vincent noticed that participants in his peer-to-peer sharing system are annoyed by the need to personally contact lenders, several interviewees emphasized the positive aspects of engaging a sense of community to strengthen anti-consumption.

In collaborative consumption, Caroline shared her experience that “in many cases, economic reasons like saving money make you start (to collaborate), but the social benefits make you stay”. Ruben described that part of the motivation for people to engage in Foodsharing is to “build social connections and spend their time together”. Vasili declared that his motivation to start a neighborhood sharing system was to “contribute something of value to our new neighborhood, and to connect to the neighbors”. Dominic shared his experiences with living in a mindfulness-oriented community: “Simplicity is normal in this peer group. So, my personal experience is, if the community you live in shares your values, it is much easier to live by these values”. Martina also emphasized the importance of “a social framework of people who support your decision to live without stuff”. Valerie connects collaborative consumption with sufficiency: “Sharing goods is very desirable, for many reasons, it strengthens communication, solidarity, neighborliness. Well, and it questions the principle of private property (…) the principle that part of a good life is constant access to goods through personal property”.

3.6. Anti-Consumer Activism

Eight interviewees expressed hope for consumers to actively engage in processes of change towards sustainability on a larger scale. “There is the political, more difficult process to change things. As a consumer, you are in direct control of your behavior, which is a good point to start getting active”, campaigner Martina says. Paul hoped that sharing goods remains part of a democratic and non-commercial culture, counting on “people to contribute, and stronger civic participation in policy making”. Dominic sees benefits in “reducing working hours, to have less available income for consumption, but more time for volunteer work, to gain competencies that induce change”. Simplicity consultant Helena shares this opinion: “I often see people relying on politics to just do it right. That is a crucial point, to be self-aware and not having to rely on someone else to take responsibility”. Her colleague Sven suggested that because “simplicity is not a guiding concept in society yet (…) we need to act on a micro-level, to create more favorable conditions for actual policy tools like tax allowances”. Enabling reflection on personal consumption preferences to make especially students understand the opportunities and boundaries they have as a consumer citizen is seen as important: “…the idea of consumer citizenship (…) it should be a part of consumer education”, said Dominic, an opinion shared by Dieter. Veronika agreed with that vision: “It should be about enabling (young people), to be able to reflect, to maybe see that some regulations are necessary, and one person can’t do everything on their own”.

3.7. Educational Strategies

3.7.1. Practical Experiences in Consumer Education

Positive examples for anti-consumption may be set through exposing consumers to spaces where change is created. For instance, schools might cooperate with social innovation initiatives. Among the interviewees, Paul invited students to visit his entrepreneurship project. He recommends that initiatives “show what people can really change, and how small actions have real effects. Not just sitting and listening but being active creating tangible results”.

Four interviewees (Dominic, Martina, Valerie, and Jane) observed that consumers’ general consciousness of the value of resources and material products vanishes. They support traditional re-skilling—via hands-on practical experiences—for the purpose of self-sufficient consumption. As Valerie declared: “It is about the experience of self-efficacy. When students are brought into contact with local resources, and we show them how to bring something into the world on their own, of course they love it. (…) You have to create experiences and teach interrelations in a child-appropriate way”.

According to the interviewees, education-related hands-on experiences can take place in schools with gardens (Dieter, Veronika), student-run companies (Dieter, Veronika), workshop facilities (Martina), or through student-initiated swap meets (Dieter).

3.7.2. The Case of Education for Anti-Consumption Lifestyles

Anna, Alexander, Ruben and Christina emphasized exemplifying within the family as one of the most important factors for shaping consumer lifestyles. Dieter disagrees: “Parents often do not know the right thing to do with money, so you should not rely on them but focus on schools, which reach all kids. The meaning of dealing with money should actually be addressed there”. Public schools as institutions rather democratically target young people from different social backgrounds. Nevertheless, a limitation expressed in the interviews is that education will hardly act against the status quo, a status quo constructed by advertising and infrastructures promoting overconsumption. “Schools are not preparing kids to change the world, they only prepare them for living within the dominant economic paradigm”, Martina critically stated. Veronika and Dieter both demanded strengthening a consciousness for consumption in schools through integrating the topic in curricula, exams, and teachers’ qualifications. Veronika wants to see “consumption and its conditions more perceptible in school education”, yet argues for stronger consumer education while recognizing its limitations and arguing for concerted policy tools: “Education is often seen as a cover-up, like it is going to fix everything and there will be responsible consumers if we only invest a little money here and there. I do not see it that way, we always need a combination of policy instruments. (…) It is a shared responsibility of companies, politics, civil society, and consumers”.

Figure 2 (inspired by Gioia, Corley and Hamilton [62]) provides a summary of the findings, structured by the main codes and sub-codes which were informed by themes emerging from the text material.

4. Discussion

4.1. Interpretation and Implications

The scope of our study was not to deliver a full policy agenda for voluntary simplicity and collaborative consumption as patterns of sustainable anti-consumption, but to find out what practitioners and experts in the field recommend as governance tools to extend the promotion of more sustainable consumption patterns. Our study is among the few that base their analysis on the direct real-life experiences of such individuals, and the first combining voluntary simplicity and collaborative consumption to study social innovations for sustainable anti-consumption. The interviewees emphasized a variety of opportunities to foster sustainable anti-consumption lifestyles through social innovations, which are summarized and discussed in the following.

The traditional trichotomy of governments, corporate actors, and civil society as change agents in governance strategies for sustainable innovation is still recognizable in the final code system. Yet, the interview data revealed important additional categories representing governance approaches to be considered in social innovation for sustainable anti-consumption. Top-down approaches remain represented by regulation and municipalities. Corporate aspects were discussed as issues of entrepreneurship. A network-focus on civil-society actors remains, through findings on community and political anti-consumer activism.

Within a consumption-focused public environment, social innovations for anti-consumption require visibility to be recognized. While some experts resent marketing as pushing overconsumption, most of them argued for more positive communication of simplicity. Marketing therefore appears as a double-edged sword. While its conventional application to create materialistic desires is criticized in the interviews, initiatives also use its tools to gain visibility and draw attention to anti-consumption options.

To achieve greater acceptance of sustainable anti-consumption lifestyles, some interviewees demanded their more positive depiction in opposition to current narratives of materialism and growth, which seem prevalent in public media and politics. The interviewees’ statements on role models and positive framing of individual benefits suggest that within the societal pressures to consume and spend money, pioneers who make themselves more independent from these pressures raise positive attention as an exception within the rule. Authentic role models are seen as important carriers of a cultural transformation of consumption patterns, whether in families, peer groups, education, or the public sphere.

By addressing the global economy’s negative consequences on individuals and the natural environment, consumers are challenged to reflect on their role within that system and on the effects of their individual purchase decisions. Nevertheless, such approaches should not leave recipients with negative feelings of guilt and resignation, but rather position alternative consumption patterns as opportunities to avoid injustices or act as self-determined decision makers in the marketplace. Emphasizing benefits may make sustainable anti-consumption attractive to a wider audience, dismissing associations of abstinence and social exclusion. Besides socializing and saving money, well-being and happiness are benefits reported to be experienced by the interviewees, making anti-consumption lifestyles a valuable prospect. Furthermore, practicing anti-consumption within a social network not only provides the necessary material and skills to share, but also emotionally motivates engagement in collaboration and resistance to quick consumption urges.

Top-down policies are discussed concerning entrepreneurship, municipal infrastructures, consumer citizenship, and consumer education. Regulatory policies are rarely seen as a desired tool. The interviewees rather welcome infrastructural support for already existing grassroots projects, especially on a municipal level. Municipalities should use their ability to provide publicly available spaces where innovations gain visibility, can experiment without economic pressures, and may flourish as grass-roots innovations. Municipalities can benefit from creating infrastructures for sustainable consumption practices and base their activities on the experiences and needs of already existing grassroots innovations.

Entrepreneurship was discussed in the context of collaborative consumption, which inspired some interviewees to develop non-commercial peer-to-peer sharing systems, and others to implement business models for sharing services. Although the topic remained mostly untapped in the interviews, interest in opportunities for business models and marketing of voluntary simplicity is growing [67,68].

The prominent topic of education, considered in all interviews, was discussed in a broad sense: not just formal school education, but as socialization in households, in community structures, and society. Building competencies in sustainable living may include re-discovering traditional techniques of less affluent times. Social innovations in sufficient consumption therefore can also be understood as de-novation. Adequately informed consumers are able to understand the individual and societal consequences of overconsumption and can make responsible (non-)purchase decisions, potentially favoring qualitatively increased, but quantitatively reduced consumption. Naturally, there are limits to what education can do. As illustrated by the interviewees’ statements, there cannot be a singular solution to challenge overconsumption. Nevertheless, demonstrating the opportunity to act differently, to present the whole picture of consumer options including anti-consumerist alternatives, and showing what grows and flows in niches, is a worthy prospect and part of what education should include. Public policy has the opportunity to strengthen these developments.

Some codes (representing tools for governance) are more strongly interrelated than others. Good marketing was mentioned as beneficial for entrepreneurial activities, but also more generally for increasing the visibility of initiatives, emphasizing individual benefits, and engaging role models through communication. Regulation and activism are rather converse: skepticism concerning the application of politics’ regulatory tools causes some experts to set their hopes on citizens’ activism from the bottom-up. As intermediary, municipalities can serve as a microcosm of innovation where activists and administration can negotiate conditions for sustainable social innovation in a manageable but effective matter. Communication and education are the most prominent prospects for supporting sustainable anti-consumption according to the interviewees. If education raises awareness for critical issues among consumers, suitable communication about social innovation structures creates the required capacity for action.

Although most interviewees’ focus their expertise on either simplicity or collaborative consumption, their recommendations for governance could not strictly be assigned to benefit only one of these patterns. Furthermore, the experts raised many topics that have been identified by research on social innovations, grassroots initiatives, and sustainability transition before, showing synergies between these research streams and the applicability of their conclusions to the explored initiatives’ actual experiences. Therefore, we argue that applying the tools elicited in our research can simultaneously benefit both patterns of anti-consumption covered in our research. The ideas presented in the interviews show opportunities for desired collaboration of governmental top-down policies and bottom-up initiatives led by active citizens who consciously decide to consume less, calling for the concerted action of all those affected by sustainable development.

4.2. Future Research Directions

Anti-consumption extends past the conventional discourse on achieving sustainability through technological innovation and more efficient technologies. Despite growing interest in the topic, the necessary socioeconomic changes for materially reduced consumption patterns to succeed within the mainstream remain a challenging topic for researchers and the interviewed pioneers. More and more studies confirm the relationships between anti-consumption patterns and increased personal well-being. Further findings in this direction might support the implementation of anti-consumption in policy and educational contexts. Nevertheless, additional research is also needed regarding the causes, development, and effects of anti-consumption and pro-consumption as conflicting motivational paths to personal well-being. Furthermore, our interviewed experts are often deeply committed to their cause, probably biasing their individual evaluation of the initiatives’ overall effect on sustainability. Long-term studies on the actual environmental impact of collaborative consumption and voluntary simplicity need to be conducted and recognized by policy makers as well [69].

Marketing expertise could help to promote the idea of consuming less more positively. Entrepreneurs with resource-saving business models, like lending shops, actually hope to attract a greater audience for their cause through marketing tools. Most voluntary simplifiers in our sample, while seeing themselves as pioneers trying to (re-)create a desirable lifestyle within an economic system they actually oppose, also call for better communication to promote their ideals—a classic tactic of marketing. Might the end justify the means for them? The marketing discipline should take these calls as inspiration to further broaden its scope and look for opportunities to serve public interests. It may be a valuable challenge to do marketing for the idea of consuming ‘less’.

Timing is a factor in our analysis. The interviews were conducted before sustainable consumption and voluntary reductions of resource-intense lifestyles had their recent momentum thanks to the international Fridays for Future-movement. As social innovations are in a constant dynamic exchange with public events, studies should continue to monitor their development. Furthermore, the scope of our research allowed us to focus on two patterns of anti-consumption. Future research might extend that scope and explore how other related behaviors like boycotting, creative recycling, or minimalism relate to the governance of social innovation for sustainable development.

4.3. Limitations of the Study

Considering the complexity of anti-consumption, we focused on two relevant dimensions: voluntary simplicity and collaborative consumption. These two patterns do not completely cover the diversity of anti-consumption, yet they allow us to detect interesting relationships between these anti-consumption options.

The character of our sample may be interpreted as limitation: with all of the interviewees working in Germany, their recommendations focus on national conditions. Conducting our studies in one of the economically most developed countries in the world, with a Western affluent consumer culture context, limits the scope of our research to rather privileged consumer groups. Our results on governing anti-consumption show parallels to findings from previous research on social innovation for other sustainable consumption patterns. This confirms the potential for strengthening anti-consumption in synergy with other sustainable consumption patterns, which can profit from similar governance mechanisms, causing win-win effects for sustainability. Nevertheless, not all potential governance tools known from literature were addressed by the interviewees. A possible interpretation is that activists and representatives of initiatives are not yet aware of the different opportunities to gain support. They may even not be interested in leaving their niche to avoid getting overwhelmed by growth and the expectations of the mainstream. Follow-up studies on how activists’ and experts’ perspectives on governance change over time may deliver further valuable insights.

Few of the interviewees are trained in policy matters, probably biasing their statements. Yet, their heterogeneous professional backgrounds allowed us to detect a very broad set of policy tools in their explorative approaches. Their perspectives from within a pioneer movement are authentic and should be respected in research and by public authorities.

Author Contributions

All three authors conceptualized the research project. I.B. was responsible for supervision and funding acquisition. F.Z. and A.H. developed the methodology, conducted the investigation, data validation, and formal analysis. F.Z. undertook the visualization and data curation. F.Z. prepared and edited the original draft, with reviews by A.H. and I.B.

Funding

This research was funded by the German Federal Ministry of Education and Research (BMBF), grant number 01UT1429A.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank all interview participants for sharing their expertise and experiences. The authors are also very thankful to the Special Issue editor and anonymous reviewers for their very constructive and helpful comments during the review process of this paper.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript, or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- United Nations. Goal 12: Ensure Sustainable Consumption and Production Patterns. Available online: http://www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/sustainable-consumption-production/ (accessed on 25 July 2019).

- Martin, D.M.; Schouten, J.W. The answer is sustainable marketing, when the question is: What can we do? Rech. Et Appl. En Mark. 2014, 29, 107–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prothero, A.; Dobscha, S.; Freund, J.; Kilbourne, W.E.; Luchs, M.G.; Ozanne, L.K.; Thøgersen, J. Sustainable Consumption: Opportunities for Consumer Research and Public Policy. J. Public Policy Mark. 2011, 30, 31–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dias, J.; Partidário, M. Mind the Gap: The Potential Transformative Capacity of Social Innovation. Sustainability 2019, 11, 4465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pol, E.; Ville, S. Social innovation: Buzz word or enduring term? J. Socio Econ. 2009, 38, 878–885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dawson, P.; Daniel, L. Understanding social innovation: A provisional framework. Int. J. Technol. Manag. 2010, 51, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz, C.; Parra, C. Non-Profit Organizations and Social Entrepreneurship; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Van der Have, R.P.; Rubalcaba, L. Social innovation research: An emerging area of innovation studies? Res. Policy 2016, 45, 1923–1935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howaldt, J.; Schwartz, M. Social innovation–social challenges and future research Fields. In Enabling Innovation. Innovative Capability–German and International Views; Jeschke, S., Isenhardt, I., Hees, F., Trantow, S., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2011; pp. 203–224. [Google Scholar]

- Shove, E.; Pantzar, M.; Watson, M. The Dynamics of Social Practice; Sage: London, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Jaeger-Erben, M.; Rückert-John, J.; Schäfer, M. Sustainable consumption through social innovation: A typology of innovations for sustainable consumption practices. J. Clean. Prod. 2015, 108, 784–798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seyfang, G.; Smith, A. Grassroots innovations for sustainable development. Towards a new research and policy agenda. Environ. Politics 2007, 16, 584–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grabs, J.; Langen, N.; Maschkowski, G.; Schäpke, N. Understanding role-models for change: A multilevel analysis of success factors of grassroots initiatives for sustainable consumption. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 134, 98–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geels, F.W. Technological transitions as evolutionary reconfiguration processes. A multilevel perspective and a case-study. Res. Policy 2002, 31, 1257–1274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spangenberg, J.H.; Lorek, S. Sufficiency and consumer behaviour: From theory to policy. Energy Policy 2019, 129, 1070–1079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozinets, R.V.; Handelman, J.M.; Lee, M.S.W. Don’t read this; or, who cares what the hell anti-consumption is, anyways? Consum. Mark. Cult. 2010, 13, 225–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, M.S.W.; Fernandez, K.V.; Hyman, M.R. Anti-Consumption. J. Bus. Res. 2009, 62, 145–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatzidakis, A.; Lee, M.S.W. Anti-Consumption as the Study of Reasons against. J. Macromark. 2013, 33, 190–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Black, I. Sustainability through Anti-Consumption. J. Consum. Behav. 2010, 9, 403–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-de-Frutos, N.; Ortega-Egea, J.M.; Martínez-del-Río, J. Anti-consumption for Environmental Sustainability: Conceptualization, Review, and Multilevel Research Directions. J. Bus. Ethics 2018, 148, 411–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kropfeld, M.I.; Nepomuceno, M.V.; Dantas, D.C. The Ecological Impact of Anticonsumption Lifestyles and Environmental Concern. J. Public Policy Mark. 2018, 37, 245–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, M.S.W.; Ahn, C.S.Y. Anti-Consumption, Materialism, and Consumer Well-Being. J. Consum. Aff. 2016, 50, 18–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGouran, C.; Prothero, A. Enacted voluntary simplicity – exploring the consequences of requesting consumers to intentionally consume less. Eur. J. Mark. 2016, 50, 189–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balderjahn, I.; Buerke, A.; Kirchgeorg, M.; Peyer, M.; Seegebarth, B.; Wiedmann, K.-P. Consciousness for sustainable consumption: Scale development and new insights in the economic dimension of consumers’ sustainability. AMS Rev. 2013, 3, 181–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seegebarth, B.; Peyer, M.; Balderjahn, I.; Wiedmann, K.-P. The Sustainability Roots of Anti-Consumption Lifestyles and Initial Insights Regarding Their Effects on Consumers’ Well-Being. J. Consum. Aff. 2016, 50, 68–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peyer, M.; Balderjahn, I.; Seegebarth, B.; Klemm, A. The role of sustainability in profiling voluntary simplifiers. J. Bus. Res. 2017, 70, 37–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elgin, D.; Mitchell, A. Voluntary Simplicity. Plan. Rev. 1977, 5, 13–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaw, D.; Newholm, T. Voluntary Simplicity and the Ethics of Consumption. Psychol. Mark. 2002, 19, 167–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ballantine, P.W.; Creery, S. The Consumption and Disposition Behaviour of Voluntary Simplifiers. J. Consum. Behav. 2010, 9, 45–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexander, S.; Ussher, S. The Voluntary Simplicity Movement. J. Consum. Cult. 2012, 12, 66–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nepomuceno, M.V.; Laroche, M. The Impact of Materialism and Anti-Consumption Lifestyles on Personal Debt and Account Balances. J. Bus. Res. 2015, 68, 654–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorge, H.; Herbert, M.; Özçağlar-Toulouse, N.; Robert, I. What Do We Really Need? Questioning Consumption through Sufficiency. J. Macromark. 2015, 35, 11–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Speck, M.; Hasselkuss, M. Sufficiency in social practice: Searching potentials for sufficient behavior in a consumerist culture. Sustain. Sci. Pract. Policy 2016, 11, 14–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belk, R. You Are What You Can Access. J. Bus. Res. 2014, 67, 1595–1600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Botsman, R.; Rogers, R. What’s Mine is Yours. In The Rise of Collaborative Consumption; HarperCollins: New York, NY, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Mont, O. Institutionalisation of Sustainable Consumption Patterns Based on Shared Use. Ecol. Econ. 2004, 50, 135–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozanne, L.K.; Ballantine, P.W. Sharing as a Form of Anti-Consumption? J. Consum. Behav. 2010, 9, 485–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geissinger, A.; Laurell, C.; Öberg, C.; Sandström, C. How sustainable is the sharing economy? On the sustainability connotations of sharing economy platforms. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 206, 419–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hulgård, L. Social Enterprise and the third sector. Innovative service delivery or a non-capitalist economy? In Social Enterprise and the Third Sector; Defourny, J., Hulgård, L., Pestoff, V., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2014; pp. 66–84. [Google Scholar]

- World Economic Forum. Why Social Innovation Matters to Business. In Business and Social Innovation; World Economic Forum: Colony, Switzerland, 2019; Available online: http://reports.weforum.org/social-innovation/why-social-innovation-matters-to-business/?doing_wp_cron=1549408927.7613921165466308593750 (accessed on 17 August 2019).

- Bunt, L.; Harris, M. Mass Localism: A Way to Help Small Communities Solve Big Social Challenges; NESTA: London, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Seyfang, G.; Haxeltine, A. Growing Grassroots Innovations: Exploring the Role of Community-Based Initiatives in Governing Sustainable Energy Transitions. Environ. Plan. C 2012, 30, 381–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moulaert, F.; Van den Broeck, P. Social Innovation and Territorial Development; Atlas of Social Innovation—New Practices for a Better Future; Ashgate Publishing, Ltd.: Farnham, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Harris, M.; Albury, D. The Innovation Imperative—Why Radical Innovation Is Needed to Reinvent Public Services for the Recession and Beyond; NESTA: London, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Sinclair, S.; Mazzei, M.; Baglioni, S.; Roy, M.J. Social innovation, social enterprise, and local public services: Undertaking transformation? Soc. Policy Adm. 2018, 52, 1317–1331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borzaga, C.; Bodini, R. What to make of social innovation? Towards a framework for policy development. Soc. Policy Soc. 2014, 13, 411–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, G.; Frances, J.; Levačić, R.; Mitchell, J. Markets, Hierarchies, and Networks: The Coordination of Social Life; Sage Publications: London, UK, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Lupova-Henry, E.; Dotti, N.F. Governance of sustainable innovation: Moving beyond the hierarchy-market-network trichotomy? A systematic literature review using the ‘who-how-what’ framework. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 210, 738–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boelman, V.; Kwan, A.; Lauritzen, J.R.K.; Millard, J.; Schon, R. Growing Social Innovation: A Guide for Policy Makers; European Commission—7th Framework Programme; European Commission, DG Research: Brussels, Belgium, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Terstriep, J.; Alijani, S.; Akguc, M. Boosting SI’S Social & Economic Impact; Simpact—Social Innovation Economic Foundation Empowering People; Institute for Work and Technology, Westphalian University: Gelsenkirchen, Germany, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Lorek, S.; Spangenberg, J.H. Energy sufficiency through social innovation in housing. Energy Policy 2019, 126, 287–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bamberg, S.; Möser, G. Twenty Years after Hines, Hungerford, and Tomera: A new meta-anaylsis of psycho-social determinants of pro-environmental behavior. J. Environ. Psychol. 2007, 27, 14–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, C.J.; Upham, P. Grassroots social innovation and the mobilisation of values in collaborative consumption: A conceptual model. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 134, 204–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Netter, S.; Pedersen, E.R.G.; Lüdeke-Freund, F. Sharing economy revisited: Towards a new framework for understanding sharing models. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 221, 224–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halpern, D.; Bates, C.; Mulgan, G.; Aldridge, S.; Beales, G.; Heathfield, A. Personal Responsibilities and Changing Behavior: The State of Knowledge and Its Implications for Public Policy; Cabinet Office: London, UK, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Isenhour, C. On conflicted Swedish consumers, the effort to stop shopping and neoliberal environmental governance. J. Consum. Behav. 2010, 9, 454–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorek, S.; Fuchs, D. Strong sustainable consumption governance – precondition for a degrowth path? J. Clean. Prod. 2011, 38, 36–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feola, G.; Nunes, R.J. Success and failure of Grassroots Innovations for addressing climate change: The case of the Transition Movement. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2013, 24, 232–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, C.J.; Upham, P.; Budd, L. Commercial orientation in grassroots social innovation: Insights from the sharing economy. Ecol. Econ. 2015, 118, 240–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frenken, K.; Schor, J. Putting the sharing economy into perspective. Environ. Innov. Soc. Trans. 2017, 23, 3–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glaser, B.G.; Strauss, A.L. The Discovery of Grounded Theory. In Strategies for Qualitative Research; Aldine: New York, NY, USA, 1967. [Google Scholar]

- Gioia, D.A.; Corley, K.G.; Hamilton, A. Seeking Qualitative Rigor in Inductive Research: Notes on the Gioia Methodology. Organ. Res. Methods 2012, 16, 15–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayring, P. Qualitative Content Analysis: Theoretical Foundation, Basic Procedures and Software Solution; GESIS–Leibniz Institute for the Social Sciences: Klagenfurt, Germany, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Thomas, D.R. A General Inductive Approach for Analyzing Qualitative Evaluation Data. Am. J. Eval. 2006, 27, 237–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guest, G.; Bunce, A.; Johnson, L. How Many Interviews Are Enough? Field Methods 2006, 18, 59–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, A.; Raven, R. What is protective space? Reconsidering niches in transitions to sustainability. Res. Policy 2012, 41, 1025–1036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bocken, N.M.P.; Short, S.W. Towards a sufficiency-driven business model: Experiences and opportunities. Environ. Innov. Soc. Trans. 2016, 18, 41–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gossen, M.; Ziesemer, F.; Schrader, U. Why and How Commercial Marketing Should Promote Sufficient Consumption: A Systematic Literature Review. J. Macromark. 2019, 39, 252–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buhl, J.; Liedtke, C.; Teubler, J.; Bienge, K.; Schmidt, N. Measure or Management?—Resource Use Indicators for Policymakers Based on Microdata by Households. Sustainability 2018, 10, 4467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).