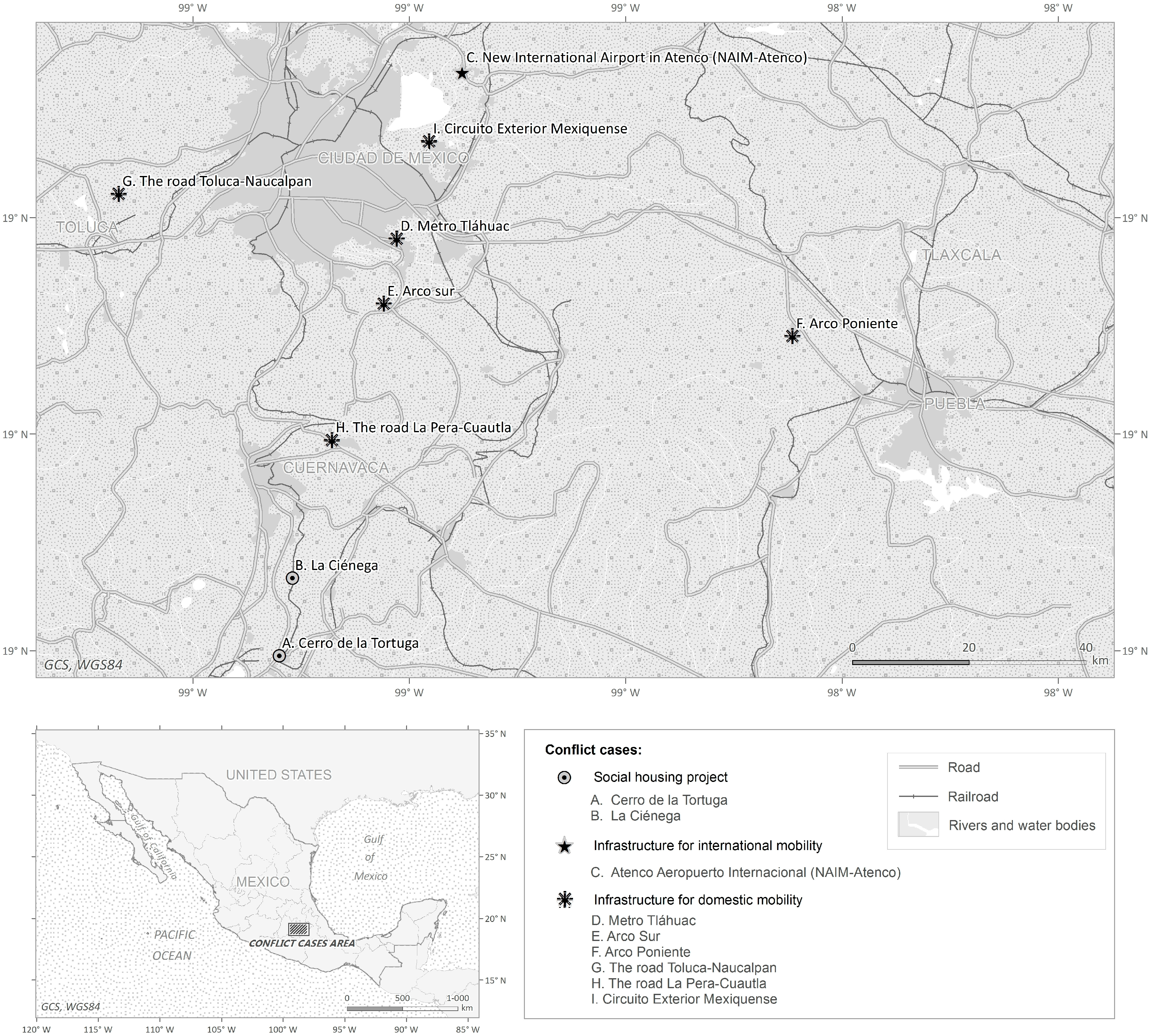

Urbanisation transforms space primarily, but not exclusively, through the built environment and infrastructure. Different expressions of the physical expansion of the city can be observed, which help us understand what urbanisation looks like at the urban frontier (see

Figure 1 and

Table 1). The cases of La Ciénega and Cerro de la Tortuga consist of real estate development projects of 2000 and 7000 social-interest houses, respectively, to be constructed on natural conservancy lands surrounding the urban area of the state of Morelos. Other expressions of the territorial gain of the city can be found in the expansion of its urban infrastructure. This is seen in the case of the extension of the Metro Tláhuac subway line to Milpa Alta, wherein 20 new subway stations and a new terminal which included a commercial centre were built on one of the few rural areas remaining within Mexico City. Another expression was seen in the ambitious federal project of the New International Airport which was planned for construction on 5000 ha of the Texcoco wetland in the State of Mexico. Also characteristic of the expansion of the city is the construction of highways, freeways, and roads (which contributes to conurbation (A derogatory term coined by Patrick Geddes in 1915 -nowadays often used neutrally- to describe “a region comprising a number of cities, large towns, and other urban areas that, through population growth and physical expansion, have merged to form one continuous industrial built-up environment. In most cases, a conurbation is a polycentric urbanised area, in which transportation has developed to link areas to create a single urban labour market or travel to work area” [

31].)). The Arco Sur, the Arco Poniente, the Tepoztlán road La Pera-Cuatla, the Toluca-Naucalpan, and the Circuito Exterior Mexiquense are five of many highway projects that make up the outer ring of the ZMVM and which are meant to interconnect the city with the southern, eastern, and western regions of the country. The Arco Sur would privatise transit through communal land and the Natural Protected Areas of Xochimilco, Tlalpan, and Milpa Alta in Mexico City, while the Arco Poniente would do the same in nine agricultural entities in the state of Puebla. In the state of Morelos, this process is mirrored with the Tepoztlán road La Pera-Cuautla, and in the State of Mexico with the Circuito Exterior Mexiquense. Similarly, the Toluca-Naucalpan highway cuts across the sacred territory and forest of Xochicuautla and two other indigenous communities of the State of Mexico.

3.1. Values in Dispute

Why are these “well-intentioned” development projects causing social unrest within the peasant localities wherein they were proposed or implemented? As declared in their manifesto, the “13 Villages of Morelos movement” argued that the urbanisation (La Ciénega) imposed by companies and the government—by qualifying their land as unproductive despite the existence of peasants and indigenous people still cultivating it—was designed to sell development and modernisation ideas that respond to the interests of the powerful at the expense of increased misery within the communities. They said that “through urban growth, savage tourism, modern industries, and industrial agriculture, local governments apply the general federal policy; systematically destroy the peasantry to absorb traditional communities in cities, or drive them out by migration in order to privately appropriate their natural resources” [

33]. Likewise, in the fight against the construction of the Arco Sur highway, inhabitants of Milpa Alta protested against a project that entails “the decapitalisation of agriculture, the expulsion of the rural population to urban areas and the United States, and land dispossession” [

34]. Correspondingly, the leader of the peasant mobilisation in Puebla stated that the Arco Poniente highway “implicates the risk of overexploitation of water and other natural resources, the development of housing projects and commercial centres beside the highway, and the homogenisation of communities” [

35].

One recurrent argument against the expanding city projects given by peasants concerned land dispossession. Ejidatarios from San Salvador Atenco and Texcoco protested against the airport, from Tláhuac resisted the extension of the subway line in their lands, from the State of Mexico fought against the Circuito Exterior Mexiquense, from the state of Puebla fought against the construction of the Arco Poniente highway, and peasants from Milpa Alta struggled against the Arco Sur highway, all highlighting the agricultural land-grabbing that urban projects bring about, endangering the income and food security of many families. For example, the Arco Poniente would affect 244 ha of agricultural land belonging to 1200 ejidatarios. Apart from subsistence agriculture, peasants also produce 1500 tonnes of vegetables and legumes that are consumed throughout the central regions of the country.

Resistance was also due to previous experiences of the communities; wherein development projects often resulted in land expropriation without only compensation. This was true in the subway line extension case, where some of Tláhuac’s ejidatarios were not compensated. In the case of the Circuito Exterior Mexiquense, ejidatarios from the State of Mexico could not stop the construction of the highway and felt defrauded for the low compensation received for their land. The 154.9 km highway cuts through 18 municipalities of the State of Mexico, linking the radial highways of “México-Querétaro”, “México-Pachuca”, “Peñón-Texcoco”, and “México-Puebla”, and ending at the frontier with the state of Morelos. In 2010, when the highway was under construction, peasants from the Cuautlalpan, Montecillo, and Coatlichán ejidos blocked the entrance to the construction site, claiming debts. One year later, a protest was carried out by numerous ejidatarios from Chimalhuacán, claiming that the highway had imprisoned and disconnected them. Today they must follow an extensive detour to pass from one side of the municipality to the other. One of the leaders stated: “We don’t like the condescending way by which businessmen treat us. First, they convince our smallholders to sell at a very low price—at less than three dollars per square metre. Nowadays, the toll fee per car is higher than that amount.”

Impacts regarding water are also very common. Peasant communities claim that the construction of houses, highways, or any other type of urban infrastructure in areas of groundwater recharge drastically diminishes water availability. In the real estate development of La Ciénega, a study made by the Autonomous University of the State of Morelos (UAEM) concluded that the project would limit water supply to 100 000 inhabitants, leave 12 communities without water for agriculture and that the discharge would pollute the water used for irrigation [

36]. Similarities could be found with the case of defence of the Cerro de la Tortuga, which is part of an important region of the high-biodiversity forest, an ecological niche for a diverse number of animals such as the jaguar, white-tailed deer, wild rabbit, and many birds and bats, and one of the lungs of the central-southern region of the state of Morelos. A lack of water was already present in the region, and the real estate development would leave Tetelpa (the planned location for the project) and other nearby communities without water. Protesters also argued that the new houses would affect the Apatlaco river through their drainage systems, thereby impacting the villagers who use it for agricultural or domestic needs.

In relation to the dispossession of agricultural land, peasant communities highlight the role of these spaces as water catchment areas. This was argued in the case of the Arco Sur highway and in the extension of the subway line to the rural areas of Tláhuac and Milpa Alta in Mexico City, where the construction of the last five stations would annihilate the lake area of the region and affect water availability for inhabitants of the southern and eastern parts of the Mexican capital. These communities are the last rural areas of the city, producing 80% of the

nopal in Mexico and conforming the biological corridor of the Mexican capital. They provide 30% of the water consumed within Mexico City [

37]. Moreover, the primary roads that interconnect the new subway terminal cross the wetland area beside the Tláhuac lagoon, the destination for twenty thousand migratory birds every winter. In a similar way, the Xochicuautla (Toluca-Naucalpan) highway would pass between the Chignahuapan and Chimaliapan lagoons that are part of a natural protected area, blocking the water runoff and transitory bird routes between the two lagoons. Correspondingly, in the case of the airport, the area of the Texcoco Lake would be seriously affected. This area is considered to be an important zone for the conservation of birds, meeting all the requirements considered for the Ramsar Convention on Wetlands of International Importance. Moreover, it is a priority hydrological natural area for its key function as a regulation vessel that prevents flooding in the region. Not only will the project provoke more flooding, but access to drinking water for the population of the ZMVM would be put at risk. This means that health, food security, and decent living for the affected communities and inhabitants of Mexico City are put at risk by the impacts of urbanisation on water resources.

A secondary effect of urbanisation, namely bringing more urbanisation, is also mentioned by peasant communities. The 13 Villages of Morelos movement against La Ciénega project claimed that housing units are usually accompanied by commercial centres, highways, gas stations, and other urban infrastructure which accelerate environmental deterioration and compromise the organisation of the communities. This is exemplified by the realisation that the planned housing unit would lead to a 400% increase in the population of Tepetzingo (the locality where the project would take place) [

38]. Likewise, the real estate development in the Cerro de la Tortuga was contemplated for 28 000 inhabitants, whereas Tetelpa’s population is less than 5000 people. Taking the stance that these projects do not solve the housing needs of the communities since peasants rarely have the money to buy the houses despite their “social” character, real estate developments open a new need for new urban infrastructure that is required in order to supply basic services to the incoming population. This argument is also relevant for projects not involving real estate developments. For example, peasants resisting the extension of the subway line to their communities refer to the expansion as the access which enables expansion of the urban area. The refusal to sell their land is to avoid deforestation and the irregular growth of the city. Likewise, peasants of the state of Puebla mention that there is a risk of housing projects and commercial centres being developed beside the Arco Poniente highway, and see it as an assault against their communal food production and lifestyle.

Water and land dispossession and degradation not only impact aspects of the environment, health, and socio-economic activities in communities, but also have an effect on their identities as well. An example is the community of Xoxocotla, leader of the 13 Villages of the Morelos movement. Water is seen not just as a vital condition of existence in Xoxocotla, but also as a fundamental social institution of their villages since its supply is a result of communal work done by their grandparents in building the infrastructure to bring water from the nearby Chihuahuita spring [

39]. Water also occupies a central place in the regional cosmovision, a factor that contributed to the movement’s social power. The 13 Villages of the Morelos movement were also involved in the defence of the Cerro de la Tortuga. This struggle had sacred implications as well, as the area contains

tlahuican archaeological vestiges and is a space where annual ceremonies are celebrated. Other examples are the cases of Milpa Alta, and Xochicuautla’s struggle against the highways that would slice their communities in half, limiting their access to the forest and affecting

nahua and

otomí traditions, respectively.

Further, the organisation of a community can be affected by the way in which the projects are implemented. All of the conflicts reveal a lack of consultation with the communities where the urbanisation initiatives take place, completely ignoring the fact that communities had gathered in assemblies (a right acknowledged in the Mexican agrarian law, in which all decisions regarding their property are made and where all the community participates in a horizontal manner) to analyse the infrastructure projects proposed for their territory. Such was the case with the community of Xochicuautla, who through these assemblies determined that the Toluca-Naucalpan highway could not pass through their territory and Sacred Forest. They also decided to present themselves not as an agrarian community but as an indigenous community, hoping, albeit unsuccessfully, to receive more legal defence. In the case of the New International Airport, Atenco peasants argued that an illegal mechanism was implemented by carrying out simulated ejidatarios’ assemblies with people pretending to be farmers, where the disincorporation of land from communal use was approved in order to transform it into private property. This illegal mechanism, which was found to have been used in other cases as well, fragments the internal social fabric.

Different opportunities are also being overlooked by promoting development only through urbanisation. The 13 Villages of Morelos movement, when gathered in a congress in 2007, showed a desire to incorporate themselves into the “solidarity economy” and fair trade and organic product networks. Other proposals along the same line included the promotion of organic tianguis commerce to reduce waste, the creation of an inventory of the fields with GMO crops to develop a strategy against genetic contamination, the creation of a seed bank, and the development of an environmental education program. Natural conservation was also present in Morelos communities’ alternatives to land urbanisation. A successful example was the case of the Cerro de la Tortuga struggle, where, with the help of the UAEM, peasants suggested that it be declared a Natural Protected Area (NPA).

Similarly, organic agriculture was also mentioned as an alternative in the rural community of Milpa Alta involved in the struggle against the Arco Sur and the subway line. They are recognised for having rejected the installation of supermarkets and convenience stores on communal lands, openly defending their own markets and stores where local products are sold. In the community, food provision is communal; the food supply for the entire community is produced within their territory, and bartering is still practised. In the negotiation meetings before the construction of the subway line, the community suggested to develop a high-productivity organic orchard in that space and to stop the construction of the subway line in the Mexicaltzingo neighbourhood. Another proposal was to build a Metrobus line, the environmental impacts of which would have been much less extensive. Nevertheless, the communities were not listened to and instead were bombarded with useless information such as the size of the screws used to build the subway.

In other cases, such as those concerning real estate developments in the Cerro de la Tortuga and La Ciénega, the negotiation tables completely lacked representatives from the private sector and government with knowledge of the case and a capacity for action or decision. In the struggles against the Arco Poniente and the New International Airport (NAIM-Atenco), peasants never managed to establish a negotiation table with the administration promoting the projects.

3.2. The Role of the State and Economic Interests

In all of these projects, the state was involved either directly in the proposal of the project, by facilitating it, or by participating in corruption or repression practices. This research shows that urban infrastructure projects are top-down initiatives from federal or local authorities allied with the private sector operating under an economic growth discourse. In this way, Urban Development Programs like that of Tláhuac are approved, where in addition to the subway line extension, a 140 ha polygon was traced for the construction of supermarkets, hospitals, universities, and other urban services. Tláhuac’s Urban Development Program also authorised land-use changes for the “Sierra de Santa Catarina”, previously for conservancy and now for Mexico City’s new projects, including a police academy, a recycling centre, and a prison. The state’s power is first put in action when acquiring the land for the projects. In the case of the airport in Atenco, the president at the time, Vicente Fox, decreed the expropriation of land without any prior consultation with the owners. In the fight against the Arco Poniente, people who refused to sell their land for the construction of the highway were threatened with land expropriation. Those defending their land against the subway line extension also suffered from intimidation tactics which included death threats. Due to the crisis and decapitalisation of agriculture, many of the ejidatarios involved in these conflicts did not reject the project in its totality and instead only asked for compensation for their land (some of them were bribed, as in the case of Xochicuautla’s struggle against the highway). Therefore, communities were the focus of a strong division process by which authorities tried to appropriate the land in dispute by destroying their social network.

The granting of construction permits without a proper environmental study impact having been carried out or without endorsement by the village also positions the state as a facilitator for the development of this type of projects. In the case of the Cerro de la Tortuga, Zacatepec’s city hall gave construction permits to Casas GEO without the community’s approval, further overlooking the illegal acquirement of communal land taking place. In the housing unit La Ciénega, it was also argued that the National Water Commission (CONAGUA) often manipulates information to build a water abundance discourse that enables them to authorize well drilling, which re-directed water to industries and new housing units. The state also plays a key role by focusing its solution to the housing problem in Mexico on the promotion of the construction of social housing units of thousands of low-quality houses on what they call “unproductive land”.

The presence of corruption was seen in the case of the subway line extension, where only a year and a half had passed since its inauguration when its partial closure was announced because of technical and structural failures. The project was named by the political opposition as “the biggest fraud in Mexico City’s history” [

40]. The subway failures led to three ex-officials facing judicial proceedings. In 2015, the

ejidatarios of Tláhuac submitted a criminal complaint against the capital’s governor for influence peddling, abuse of authority, patrimonial and environmental damage, and unexplained enrichment. Corruption practices were also alleged in the case of the New International Airport and the Circuito Exterior Mexiquense. These projects are related to the Atlacomulco Group, a political organisation comprised of powerful political figures within the Institutional Revolutionary Party (PRI) which is suspected of giving massive public contracts to close friends. The Atlacomulco Group is also linked to Grupo Higa, the company responsible for the construction of the highway in Xochicuautla.

Regarding repression and criminalisation of the protests against the projects, the most relevant case was the one known as the “Atenco’s slaughter” in the year 2006. After the first failed intent to expropriate land for the construction of the airport, peasants from Texcoco and San Salvador Atenco had already successfully organised themselves in the People’s Front in Defence of the Land (FPDT) and involved themselves with other struggles and resistance movements in the region. What started with eviction of flower growers selling their products on the road turned into a large-scale confront between the municipal and state police and the Atenco movement. The police operative resulted in two boys being killed, and 207 arrests, 47 of whom were women, of which 26 suffered torture and sexual aggression by the police. Despite all the human rights violations having been documented, the governor of the State of Mexico at the time, Enrique Peña Nieto, said that “the balance of the operation was positive because it lets us reach the objective, which was to re-establish order. Neither the authority nor the population of Atenco could stay hostage to the interests of a group that had violated the law”. He also declared that “the fabrication of accusations is a known tactic used by radical groups, and that it could be the case for the women denouncing being raped by the police with the objective of discrediting the government” [

41]. The declarations reveal the iron fist with which the state gets rid of any political opposition, which in this case were the peasants defending their territory and livelihoods.

Criminalisation was present in the case of the Arco Poniente highway as well, when the leader of the mobilisation was imprisoned. After his liberation, he revealed that more than 100 restraining orders existed against peasants who oppose the construction of the highway. The peasant fronts of resistance reported that the government of Rafael Moreno Valle utilised power to persecute environmentalists and give away the water and land of the inhabitants of Puebla to foreign capital. Something similar was argued in the case of the Arco Sur highway; after successfully stopping the project in Milpa Alta, the construction of a Navy Base on the

ejidatarios’ land was announced four years later, by presidential decree without any prior notice. The community said that “the base is a pretext to have a surveillance zone and control the social movements of the area. The army will work in favour of the megaprojects that are already prowling the area” [

42]. The community said that this would be the first step in facilitating the imposition of projects such as the Arco Sur, opening up natural conservation lands for urban development.

3.3. Actors and Productivity of the Socio-Environmental Conflicts

We find that the groups who tend to mobilise first against urban sprawl infrastructure projects consist of the semi-urban population, whose main economic activities revolve around agriculture. Although not always defending agricultural land (in both real estate development cases, the land use proposed for the territory in dispute was one of conservancy), the peasants resisting the expansion of the city all belong to ejidal or the communal type of properties and organisations. Moreover, the people involved in the mobilisations in Morelos against the social-housing projects, in Milpa Alta against the Arco Sur highway, and in Xochicuautla against the Toluca-Naucalpan highway acknowledged indigenous identities: tlahuica in the cases of Morelos; nahua in Milpa Alta; and otomí in Xochicuautla. Universities also bring the conflict to light through various methods by suggesting the declaration of NPAs, as the UAEM did in the case of the Cerro de la Tortuga; carrying out studies which revealed the unsustainability of the projects, again exemplified by the UAEM when detailing the impacts of the real estate development La Ciénega; and by organising forums where the socio-environmental conflicts are exposed, for example that organised by the Iberoamerican University of Puebla, to which the leader of the Arco Poniente resistance was invited after his release from prison. It is also seen that political opposition parties participate in conflicts either because of a genuine interest in defending the communities raising their voice, or simply with the aim of discrediting the party in power. Their participation usually consists of highlighting impacts, repression practices, and demanding that the government come up with a solution. In 2019, the new president López Obrador, who had been in political opposition to both Fox and Peña Nieto, suspended the construction of the NAIM airport.

Environmental and human rights organisations (both Mexican and international) also often get involved, usually after a strong confrontation between actors has been produced. After the clash between police and the 13 Villages of the Morelos movement in the case of La Ciénega, the Human Rights Commission of the State of Morelos presented a complaint. Also, the Coalition of the Mexican Organisations for the Right to Water, in a letter addressed to Felipe Calderón, the ex-president, demanded respect for the right to protest pacifically, an end to the threats of violence, respect for dialogue tables, guarantee for the right to water alongside its protection, and that the access, distribution, and decision-making regarding water be equal across people and regions. Similarly, in the case of the subway line extension, when the people who had resisted leaving their land were evicted, the Human Rights Commission of Mexico City (CDHDF) complained against the excessive use of force by the police. This was also the case for the conflict that arose from the New International Airport project in San Salvador Atenco, where the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights (ICHR), alongside the UN Fund for Women, Amnesty International, and other human rights organisations demanded justice against the Mexican State regarding the “Atenco’s slaughter”. More than 70 social and environmental organisations which make up the Front against the New Airport and other Megaprojects in the Valley of Mexico also helped articulate the negative impacts of the project once it was re-launched. In the Arco Poniente conflict, local human rights organisations were also present and helped in the liberation of the imprisoned leaders of the resistance to the highway and other related struggles. There were only two cases wherein a human rights organisation made a decisive contribution to stopping the project: that of the Arco Sur highway, where after a complaint was presented by the community representatives at the National Human Rights Commission (CNDH) citing a lack of consultation, the Commission established a reunion with the government entity responsible for communications and transport, and agreed that no highway would be built due to the lack of technical and juridical conditions; and the case of Xochicuautla (Toluca-Naucalpán), wherein the ICHR intervened and the Supreme Indigenous Council’s proposal of a technical alternative to the Toluca-Naucalpan highway which was based on tunnels and bridges for human and animal crossing, and which aimed to preserve the water sources of the community, was taken into account.

The actors backing up the projects consist of national (Grupo Higa, Urbasol, Casas GEO, Grupo Carso, ICA, Pinfra, Infraestructura Omega 2000) and international (Alstom and OHL) construction companies, as well as state entities, such as local and federal governments, water commissions and urban planning entities (CONAGUA, State Commission of Water and the Environment; CEAMA), communications and transport entities (Communications and Transport Secretariat; SCT), land banks, and the police. The cases studied seem to be characterised by the invisibility of the private sector, who typically handle everything through intermediaries and who are never present in negotiation meetings. An example can be found in the real estate development planned by Casas GEO. On top of not attending the dialogue tables, they built an alliance with a workers’ union of the construction sector, which is known to be affiliated with the PRI, operating as a “clash group”, and whose intimidatory practices were reported by the community. Additionally, paid inserts were published in many newspapers of the region and signed by ghost associations but were revealed to be of corporate origin through their drafting, content, and cost. The use of the media was also present in the case of the airport, where a defamation campaign against the Atenco movement preceded the “Atenco’s slaughter”. The mass media made a public outcry against the “violence of the Atenco macheteros” and demanded “strong action against the criminals altering the social order”. A homogenisation of voices asking for the use of force against the Atenco ejidatarios began.

Since all the projects have a public character, construction companies receive a contract, and thus the illegality of land acquisition, the given construction permits, and the implementation of the project lie on the shoulders of the state. Although corporate influence peddling is not easily traced, there have been many allegations of corruption against several of these companies. For example, the construction company ICA was created and grew up under political protection by the PRI political party that exchanged big infrastructure contracts for financial support. With the return of “the new PRI” to the presidential chair, the favouritism for ICA was replaced with that for the Spanish company OHL, which has been at the centre of a scandal for illicit agreements (concessions granted without the proper protocol, financing political campaigns, and inflation of construction budgets) between their Mexican subsidiary and government officials of the State of Mexico, who make up the Atlacomulco Group. The Atlacomulco Group and OHL have been blamed for corruption practices aiming to maintain power and enrich themselves, including the construction of the Circuito Exterior Mexiquense and the “Viaducto Bicentenario” highways [

43].

Regarding the outcomes of the social movements that arose against urban sprawl projects, it is important to analyse their social and political productivity. This refers to the long-lasting effects that “contribute to the construction of emergent environmental rights and the subjectivities of citizens who hold or pursue such rights” [

44]. Of the nine cases, environmental justice was served in four of them through the cancellation of the projects (

Table 1): the Arco Sur highway, both of the social-housing projects in Morelos, and in 2018, the cancellation of the International Airport by the new presidential administration after a public consultation was carried out. The conflicts concerning the real estate developments also led to the declaration of the territories in dispute as NPAs.

Despite the formidable strength of urban sprawl, an emancipative movement is revealed. The creation of the 13 Villages of Morelos in defence of water, land, and air movement that participated in both cases in Morelos, and the organisation of

ejidatarios and peasants in multiple fronts (Rural Front of the South in Defence of the Land in the case of the subway line extension, the People’s Front in Defence of the Land in San Salvador Atenco, and the Peasant Front of

Ejidatarios against the Arco Poniente) expose the strengthening of participation of local peasant communities -historically recognised as political actors in Mexico- and reveal a new environmental discourse in their struggles. These organisations are typical of environmentalism of the poor and indigenous [

24], which differs from conservation movements.

Despite the inexistence of a regional or metropolitan peasant movement against urbanisation projects, efforts to knit resistances together can be observed. After its birth in 2006, the 13 Villages of Morelos movement adopted other struggles such as other housing units, gas stations, and landfills in Morelos, which became the reason for their involvement in the Cerro de la Tortuga case. Similarly, in a street protest against the subway line extension, peasants from Tláhuac and Milpa Alta received the support of the FPDT from San Salvador Atenco, reaching participation of 5000 farmers. In order to exchange experiences of land defence and to plan collective actions, peasants made calls to other communities, organisations, and civil society, in general, to participate in different types of forums against urban expansion in Mexico. This was the case of the organisation of the first congress of Morelos’ communities in defence of water, land, and air wherein a variety of problems were discussed. The congress resulted in the creation of a village council, and a Manifesto was presented. Another example can be found in the participation of the Arco Sur resistance in the Permanent Peoples’ Tribunal in the case “Highways and social and environmental devastation” against the Mexican state and companies involved, where it was agreed to create a common space for the fight against highway projects in Mexico. Finally, in the case of the Arco Poniente, a united front resulted from the attendance of different groups resisting the highway and a gas pipeline, namely the “Regional Encounter for the Defence of Natural Resources and Social Rights” in Puebla.