1. Introduction

Sidewalks share many common characteristics with streets. A well-planned sidewalk could contribute many advantages for its city. Sidewalks are acknowledged by many scholars to play an indispensable segment in urban public space as we can examine diverse facets of social, economic, and cultural states, or even urban politics of the city [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5]. Sidewalks, hence, are also being reconceptualized and contested as spaces that should be used as more than a sole means of transportation [

2,

5]. Truly described, the urban energetic vibes that are observed on the ground and the all-around lively vitality of the urban system are mirrored in everyday street life, including its impulsiveness or disorder. People come then leave, people assemble around to interact with one another, or simply to enjoy themselves. Thus, sidewalks are certainly one of the most substantial parts of public open space in the city. Citizens rely on sidewalks for many activities: social, cultural, and commercial purposes [

5,

6].

Many urban specialists believe that the very first impression about the city is an image of the streets. Jacobs [

7] strongly emphasized the importance of how the street’s look could influence people’s perspective on the cities: When the streets look interesting, that city looks interesting, and vice versa. Several other compilations and empirical studies have assembled a great deal of knowledge on the nature and use of public space such as streets, plazas, urban parks, etc. [

2,

3,

4,

8,

9,

10,

11,

12,

13].

Recently, many stakeholders have been taking action to organize the streets and sidewalks more effectively in a creative way, which could be an interesting case of sidewalk usage and management. Particularly, international organizations and nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) often facilitate negotiation rounds from the perspectives of informal sector workers and street vendors. For instance, the Street Net International, International Domestic Workers Network, International Transport Worker’s Federation, etc., set their goals in helping informal sector workers by establishing networks and advocating their rights and standard of living [

14,

15,

16]. Nevertheless, different stakeholders would diversely regard informal street activities, which can be viewed as positive or negative depending mainly on how vendors occupy public space and its effects on residential and business areas [

17]. Urban governments are often concerned about the street vendors by perceiving them as a sign of chaos and disorder. Consequently, in order to create an image of a modern and global city, many cities have operated dislodgement and relocation campaigns. Mitullah [

18] argued that these kind of “street vendor clear-up” campaigns in bustling city centers imply power possession because street vendors are believed to make profits at the cost of formal and legal business. Such “clear-up” campaigns have been observed in India, Vietnam, Mexico, the Philippines, South Africa, and in other developing countries in Africa [

17,

19,

20]. However, dislodgement and relocation campaigns represent a negative power demonstration of city regulators toward street vendors. By removing vending stands by force, urban governments sometimes overwhelmingly show off the nature and effects of the power they hold, which can lead to social debates and controversies [

21]. Urban government decisions have substantial influences on both natural and built environment. These results may remain for many decades and many are unchangeable [

22]. Therefore, understanding how the government has reacted to informal street activities over the years is necessary because there are no official regulations applied to the informal activities and the vendors seem neglectful of obtaining business permits.

Nevertheless, literature reviews appear to show a shortage of empirical papers on sociability in the urban sidewalk. The physical factors of the environment, the businesses, or the places which contain the special meanings of the society have been the main subjects in many studies [

23,

24]. As there are current debates about the real purpose and true legitimate uses of sidewalks at the local scale, many researchers focused on physical characteristics of the sidewalks, such as landscaping, sidewalks curb, and so on. Consequently, to have a deep research on sociability of the sidewalks is thought necessary to reveal how sidewalks are utilized by people on a daily life basis and how vital the role of sidewalks is in urban life.

With regard to multiple sidewalk functions in urban life, this paper aims to examine how sidewalks operate in a crowded urban zone and what type of activities sidewalks can accommodate at different times throughout a day. Therefore, this paper will use the specific exemplar of one typical street in Ho Chi Minh city (HCMC). We attempt to put together a picture of HCMC sidewalk, and then highlight its bright side as well as aspects that need improving. Through this portrayal, we draw out suggestions for policymakers and urban planners highlighting a much more nuanced and richer description of the sidewalks’ lives. Besides, we unfold the examination by exploring the sidewalk’s potential of serving as an inclusive space, with an emphasis on how they foster the social aspect, then we suggest a new approach on the “sociable sidewalks” term and review to what extent the sidewalks in urban Vietnam are sociable.

2. Literature Review

Ever since the turn of the 21st century, people have been living in the dynamic times when sidewalks and their associated characteristics are reassessed from various perspectives. Sidewalks share many common characteristics with streets. Sidewalks that properly and completely satisfy the needs of people have proved to be more likely to be associated with a positively growing economy, physical health, and a strong sense of ethnic communities. On the other hand, researchers affirmed that the street is actually a social space, not just a passage for movement [

3,

9,

23,

25,

26,

27]. Some even believe that the satisfaction of people on the social aspects of the streets even outweigh the physical satisfaction which the environment gives out [

28,

29,

30,

31]. Seen from this functional angle, sidewalks share many mutual points with streets. One well-functioning sidewalk should also meet up the social demand of its users. In particular, a mixed-use of sidewalk is as well worth taking into consideration, in which the public spaces serve different purposes in separate timing in order to enhance the flexibility and multi-purpose functions of the sidewalk [

6]. In the study on livability in Asia, Mateo-Babiano and Ieda [

32] stated as a fact that the street complexity exists as a permanent attribute of the increased level of city livability. Consequently, the livable streets are simply defined as places where people join together in the diversity of social and recreational activities, such as, walking, meeting, or shopping. [

33,

34]. Many researchers on Asia consider the link between livable streets generally and sidewalks especially with place-making, social interactions, and the economic vitality [

35,

36].

Accordingly, the role of the sidewalks as a public open space is now rethought as one of the most important components in urban spatial design. In many urban areas, after decades of regarding pedestrian movement as the most important role of the sidewalks, governments have started to rediscover the broad road that sidewalks could and should generate in public arenas such as commerce, socialization, community celebration, and recreation. Although the definition of sociable sidewalks is very well captured in a quality means, other aspects need to be reconsidered as well. Sidewalks come in all shapes and sizes, they also vary in the activities and behaviors that they accommodate and support. Despite this conceptual transition, the role of sidewalks remains highly distinctive in Asian cities as the urban realm takes place not in the city squares as in European cities, but mainly in the street sides and alleys.

However, it takes even more conditions for sidewalks to be sociable, because the social and economic role of the sidewalks has merged ever since cities first appeared as many space researchers have well reflected this issue. From the perspective of sociability, a sociable sidewalk is defined as a sidewalk that is open to the public, wherever it is likely to have a frequent appearance of people throughout the day [

37]. People can use sociable sidewalks for purposes relating to an individual or a group; or containing active or passive social behaviors. Specifically, a sociable sidewalk offers places for residents, visitors, commuters, and other people who call the street their home for multiple purposes, such as socializing, interacting with the others, or purchasing. Extensive scholars have thoroughly mentioned inclusive spaces where people with and without special conditions can assemble and enjoy freedom, connections with the others, and social acceptance. In a space, people move around, observe the environment, interact with space and sort out the information then take advantage of the surrounding environment, either consciously or unconsciously [

38,

39].

As Vikas Mehta [

37] argued, sociable sidewalks should be thought of as the spaces that have special meanings for the community. It is necessary to reconsider these spaces since they not only act as a physical platform where all social participants can meet with their own personal and shared opportunities [

40] but also serve a basic rehabilitation [

41] and human right [

42] (

Figure 1).

It is common that sidewalks are the extension of the store front or a place for an exchange of goods and services. This extending area can be operated regularly, or occasionally during special time, regardless of its sense of a legal action. In some cases, the bustling atmosphere is even expected to trigger positive vibes in passing people whether or not they are entering the selling environment. One should also bear in mind that a prerequisite condition is a moderate sidewalk density, which allows people to stroll or to linger pleasantly and freely without any restraints. Only under this condition can sociable sidewalks be properly designed.

3. Study Area

3.1. Ho Chi Minh City (HCMC) and the Informal Economy in Vietnam

HCMC is the most energetic city of Vietnam in socio-economic terms. As the biggest city in one developing country, any problems in HCMC are very typical and could be found elsewhere in Vietnam and other big developing Asian cities. HCMC has one common feature that is shared among a number of Asian cities: an informal economy. According to the ILO (International Labor Organization) [

43], the informal sector in Vietnam is best described as “all private unincorporated enterprises that produce at least some of their goods and services for sale or barter, are not registered, and are engaged in non-agricultural activities” [

44]. Remarkably, the informal sector in Vietnam is notable in many ways. For instance, in 2007, it was estimated that the informal sector created almost 11 million jobs out of a total of 23 million jobs in Vietnam [

40]. Most importantly, 20% of GDP was generated by the informal economy, which was the unregistered informal businesses, such as, street vendors, peddling, and small sidewalk businesses (

Figure 2) [

45]. In fact, they are not even required to register at all. Given that HCMC’s population is 7.1 million, it is estimated that there are 750,000 informal household businesses offering jobs for one million workers. Because of this significant amount, the informal business activity must be administered seriously [

43]. Moreover, street vendors and sidewalk parking lots have occupied four million square meters of sidewalk across the city [

46].

Recently, the Unite Nations has conducted a survey in HCMC which showed that 20.6% of working people in HCMC were, in fact, rural–urban migrants [

43]. They are mostly young uneducated workers and are less likely to have healthcare or stable housing. Moreover, 67% are estimated to be unskilled and semi-skilled labor force [

43]. Despite this, migrants are, surprisingly, on equal ground with residents regarding the issues of low income, not more disadvantaged as most people think. Some of the migrants’ income is probably higher than poor official citizens in HCMC as they have less dependency and more working hours per week. Therefore, one must be careful, though, in generalizing that all street vendors and sidewalk businesses are low-income people, or rural migrants. However, rural migrants are more marginalized when participating in social organization and community activities, so migrants are more insecure with regard to social support and interaction with their surrounding communities.

3.2. City Authorities and Their Response to the Informal Economy

In 2008, the Vietnamese government started a strategic plan to clear the “inappropriate” activities from the sidewalks, with the aim of leaving the spaces available only to pedestrians. The local government imposed a ban on all the street vendors. It should be clear that the term “street vendors” here refers not only to itinerant street traders, but also to the locals who regularly encroach on the sidewalk for their own activities. These people occupy almost every possible space for small-scale services, namely hairdressers, cooked food stalls, lottery stalls, vegetable stalls, and tea stands. The rationale for the ban was “to beautify the city” as in capital Ha Noi and for “city aestheticism” as in HCMC and also to promote tourism, sanitation, and congestion [

47].

The government of HCMC even deemed 2008 to be “the year of working toward a civilized urban lifestyle,” with the street vending categorized as an “uncivilized act”. Additionally, the local government drew up the sidewalk separation line which could be found almost everywhere. Consequently, a straight line, which is 1.5 meters from the edge of the sidewalk, was painted down the sidewalk. As a result, many promenades are divided into two parts with painted lines: one allowing businesses and their parking; the other side is for pedestrians. This sidewalk separation line would virtually remind store spillover, parking lot, and informal vendors that they should not cross the line in order to leave space for pedestrians. Though both business actors and residents often violate this law, leading to periodic sidewalk clean-up campaigns carried out by local authorities. The efficiency of each campaign was, understandingly, not as desired. However, in spaces used for parking motorbikes, with modest police enforcement, repeat offenders would park in a comparatively more orderly fashion. This empirical evidence implies a mismatch between people’s real needs and policy legislation. This is a conclusive proof on why sidewalks in Vietnam must serve the sociable demand of people, as any mere clean-up campaign is doomed to failure every time.

3.3. Study Area

Similar to any other cities in Vietnam, HCMC has long been struggling with street and sidewalk issues, as the repercussion of a high population growth rate and shortcoming in planning policies and legislation of the city. Although recently the government has taken action to periodically enforce sidewalk clearance, the outcome is not as desired since the effect is momentary (

Figure 3 and

Figure 4). Therefore, to understand why the sidewalk clearance campaign is continuously ineffective, a segment of Nguyen Tri Phuong Street was chosen as an exemplar to clarify the usage demand of residents and sidewalk users.

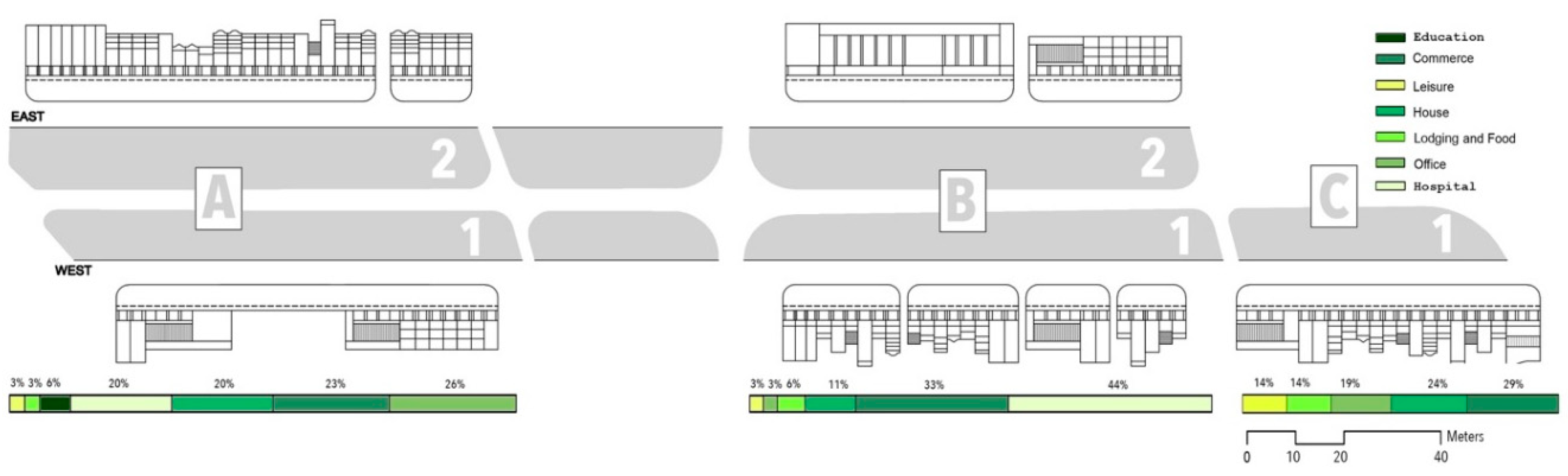

Nguyen Tri Phuong Street sidewalk is a typical street in HCMC because the demand for sidewalk space is relatively high (

Figure 5). In general, the area is a place for many types of residential housing, working office, education, and hospital, namely commerce, education, hospital, office, lodging and food stores, housing, and leisure place. Accordingly, we divided the street into three main segments with two sides for each segment except the third: A1/A2, B1/B2, and C1 (

Figure 6). As clearly shown in

Figure 6 most spaces in Nguyen Tri Phuong Street are held for housing, commerce, and offices, with an exception of segment B due to an existence of a grand city hospital there. Nevertheless, this area is mainly a settlement of dense mid-income residences, leading to a residential street with small or individual businesses. Consequently, once the study is accomplished, it is expected to help planners to make sidewalks become friendlier and more accessible for both the residents and sidewalk users.

4. Methods

The methodology is designed to capture the dynamics of everyday street life. To achieve that, behavioral mapping and photographing are adapted as the instruments for environment–behavior research.

These specific methods have been used to explain how activities and interactions unfold in order to capture people’s behaviors within the physical environment and understand how the physical factor of space interacts with the behavior [

26,

37,

48]. The two popular methods were used to gain an insight into the different interactions that occurred at different periods of time [

49], such as, ethnographic observations was undertaken to explore the conceptions of everyday life and public space in Bath, UK [

50]; Elshestawy [

51] continued this tradition in identifying the detailed portrayal of the street’s inner life of Dubai. The strength of these methods is that they fundamentally address the objectives of the study and allow the researcher to obtain numerous informal activities which would have otherwise been unavailable. In other words, it supports the bottom-up perspectives by capturing what is really happening in the sidewalks.

Data were collected approximately along Nguyen Tri Phuong Street from May to June 2017. Below is a brief description of each method.

Behavioral Mapping. Mapping behavior is simply to map what happens in the targeted space or area [

5,

33,

52]. Walk-by observation was used to document the location and the various range of activities engaged. Noticing pedestrian movement impacts was another focus of this research, thus the pedestrian crowding is the most notable reason given for enacting street vending restrictions. Some student assistants captured the people’s activities and behavior by walking along the street focusing either on the western or eastern side. Consequently, stationary activities (any activities taking more than 1 min) were recorded on a sheet; people who were just walking by were not counted. Observations were conducted on all weekdays and weekends at four periods of time in a day: 7:00–8:00; 12:00–13:00; 17:00–18:00; and 21:00–22:00. Then each activity was represented by a block on the coding sheet. The final behavioral mapping data, consisting of manually transcribed maps and notes were managed in folders according to each period of time.

Photographing. One of the drawbacks of behavioral map is that it does not show the inner dynamics and subtleties of every interaction. To achieve this, a technical photograph is frequently used in the field of public life studies to illustrate the situations. In this study, to ensure trustworthiness, photographing is necessary as photographs can describe the scenarios and show the interaction between urban form and life [

33] and the spatiotemporal evolution of activities.

5. Findings

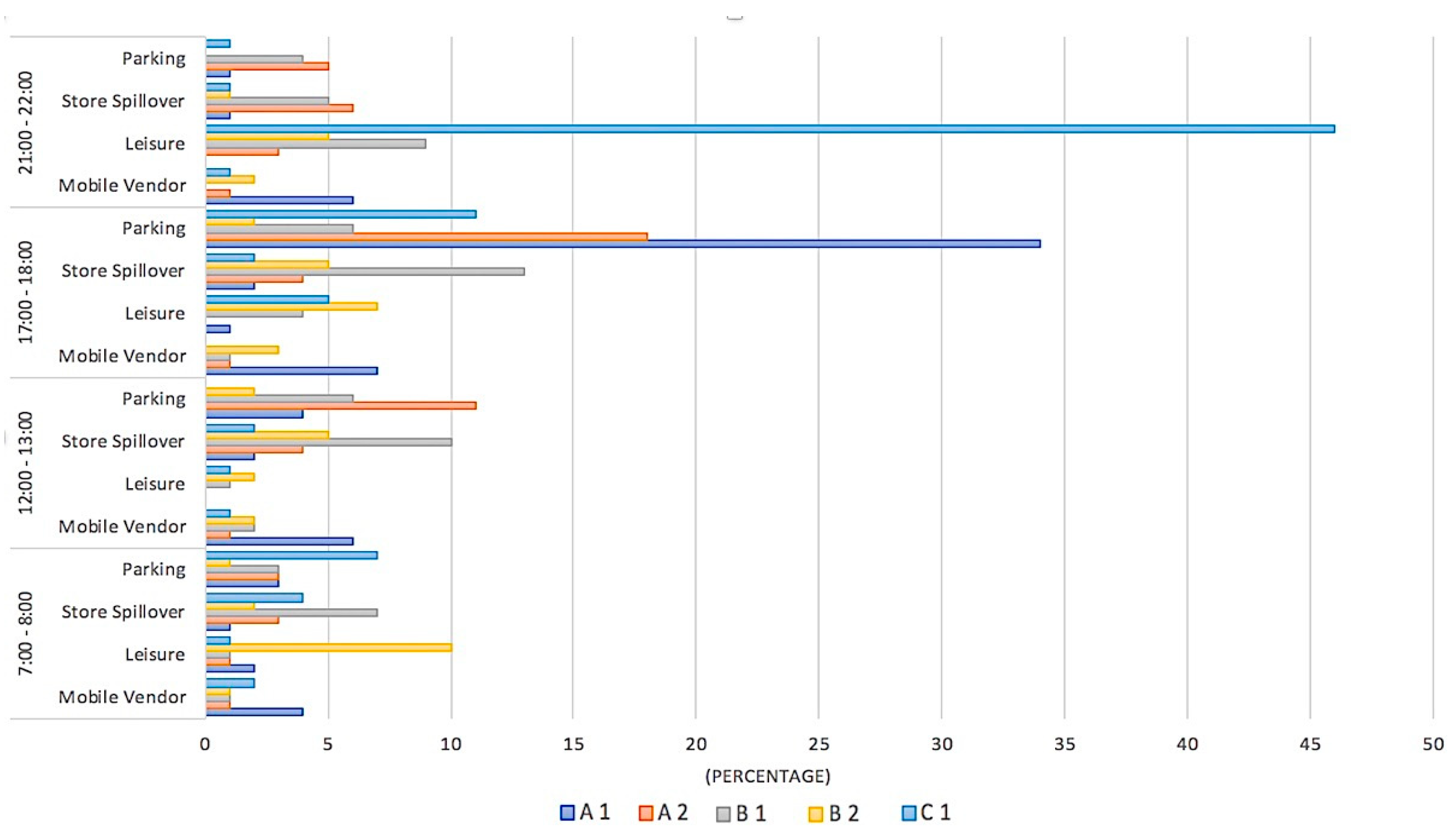

5.1. Sidewalk Crowding and Its Self-Organization in Space and Time

In contemporary urban Vietnam, sidewalks have been operated, albeit limitedly, as an instrument for the negotiation between authority and people over the public spaces and the related practices. Sidewalks in Vietnam from the outside-in direction would be much alike to other Asian cities, due to the law enforcement and mainly because of the overload and impulsive use of motorbikes in Vietnam. Meanwhile, looking at the inside-out direction, there is a strong interference of private use on public spaces, especially on the sidewalk’s space. In Vietnamese urban life, communal living and shared space are still very common and continue to be a substantial part of the local neighborhood. In Vietnam, especially in cramped accommodations, spending leisure time outside the house with a lively view of the neighbors and pavement passengers is a typical community lifestyle. It is essential to note that street frontage is a very valued commodity in the Vietnamese property mindset, as people could have more spaces for domestic activities or for small business operations. Restricted private spaces are generally observable, especially in crowded housings, where residents always tend to pour out into street sidewalks as a type of urban encroachment of public spaces, for commercial purpose such as food stalls or goods exhibition. Unlike exclusive spaces, these occupied spaces, although illegal by law, are mutually consented provided that the local neighborhood does not disapprove. These characteristics hence build up an intimate relationship between streets and sidewalks in Vietnam urban cities. Moreover, sidewalks also provoke social exchange, since they offer places for walking, interactive chatting, and informal economic activities. Consequently, a transition of urban street life and sidewalk-use by pedestrians, biker, and residents has become more and more complicated as they often occupy sidewalk spaces for extending the domestic spaces or as an annexation of commercial spaces.

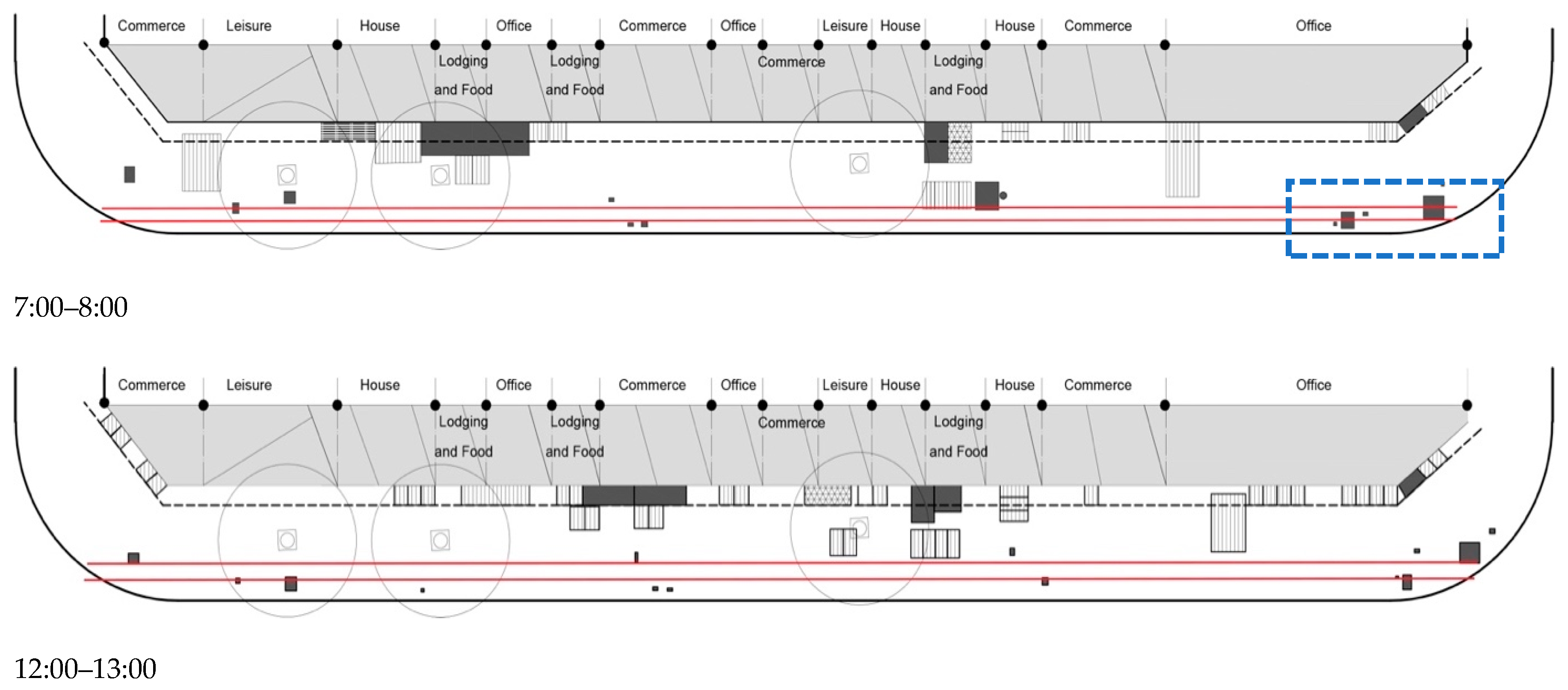

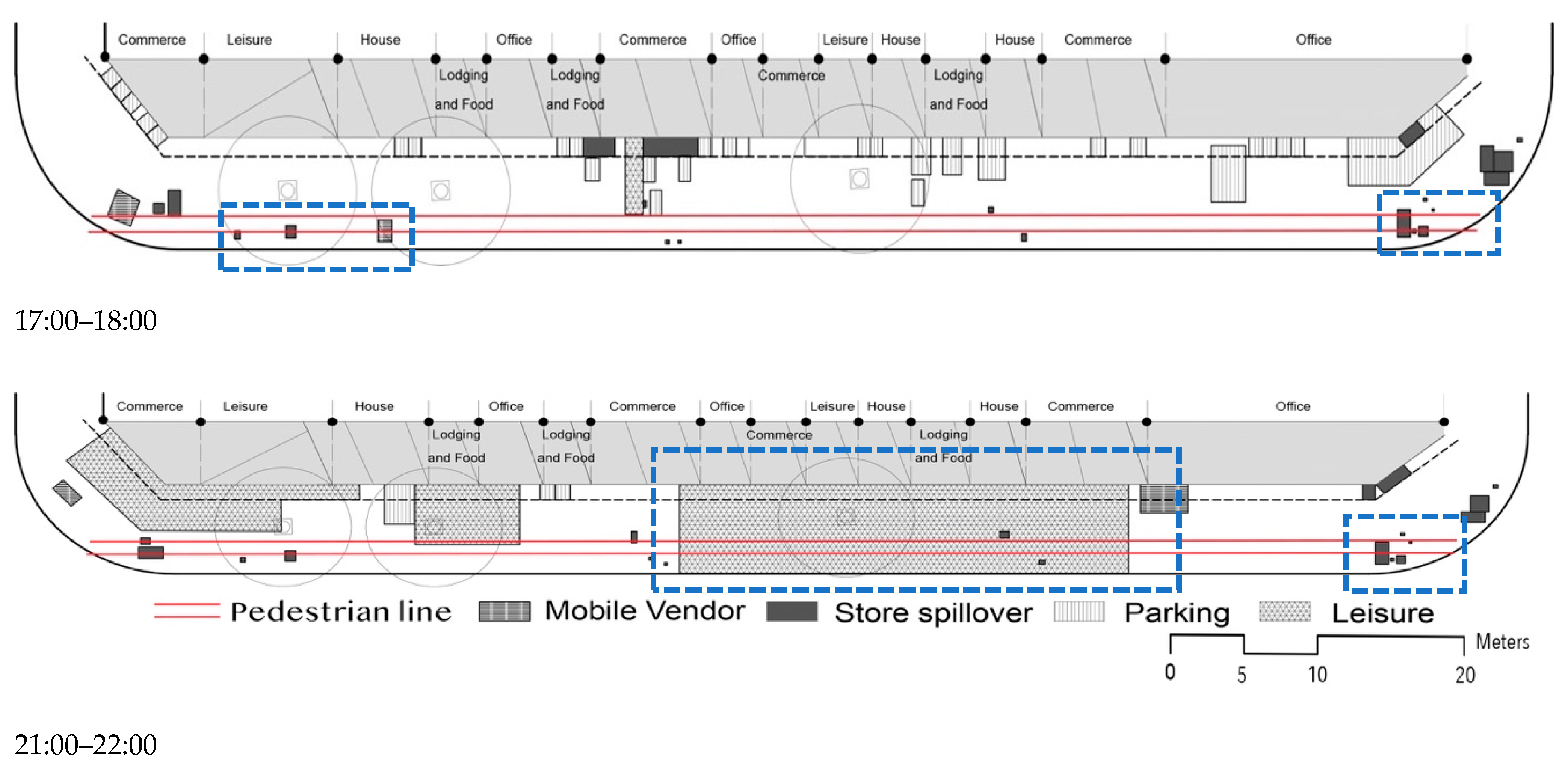

Informal economic activities only retain informal public spaces at certain time periods of the day. These informal activities are not random, in contrast, very dynamic and usually welcome by the people. This is because the local street culture is very receptive of a flourishing group of small businesses who serve a wide range of goods and necessary services. In addition, sidewalks support public activities and public relationships, but they also allow people to fulfill personal needs through economic exchanges, social encounters, and at times basic survival, private activities in public spaces level up the complexity of the relation between public and private aspects on the sidewalks. Many purpose-overlapping activities are carried out in the sidewalks, and this vibrancy is extremely appealing to passengers, which creates diverse activities. Consequently, to understand how HCMC people use sidewalk space, we should look at it from the temporal dimension. During the day, sidewalk spaces regularly change usages and users. In the morning, sidewalks are taken up by small businesses along the way, especially morning food stores. In the afternoon, the same sidewalk space might be used as a guarded parking place; and in the evening, movable chairs and tables might turn it into a sidewalk restaurant as a place for leisure time (

Figure 7 and

Figure 8).

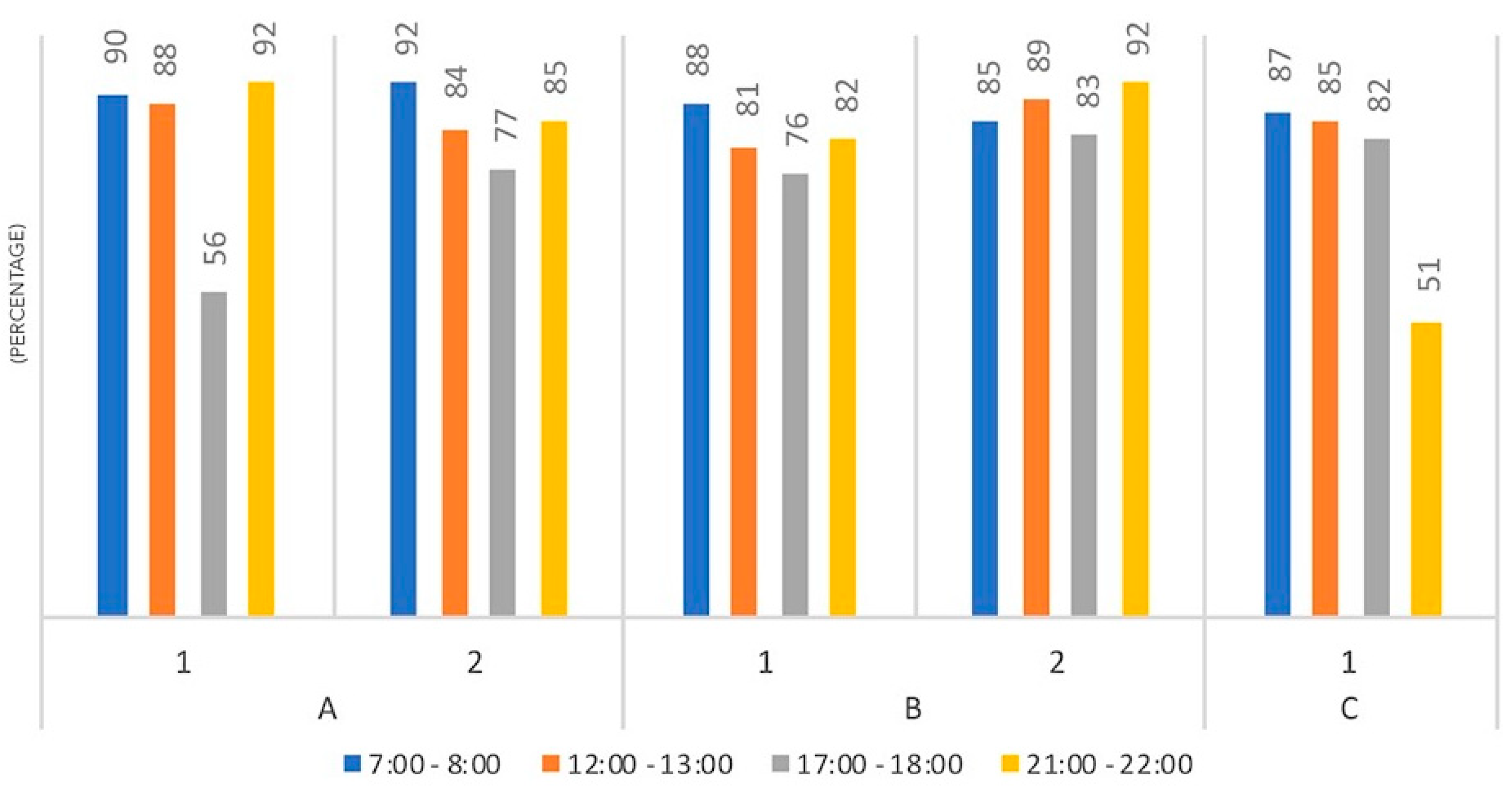

The amount of space used varies considerably over the day. Sidewalk space used to sell merchandise gradually expands during the daytime and moves toward the curb to get closer to commuter customers, as a result, the amount of remaining pen space is varied throughout the day. For example, as illustrated in

Figure 9, segment A showed the most distinctive difference in the 17:00–18:00 time frame, with a drop at 56% for the remaining sidewalk, because it is an after-school time of one local high school, many parents were parking and temporarily occupied the sidewalk to pick up the children. As for segment C where many night food stalls and restaurants are located, the 21:00–22:00 time frame also showed the least percentage of available sidewalk at 51%, leaving the space for leisure purpose (

Figure 7 and

Figure 9). These two figures evidently show the diverse main economic structures that sidewalk spaces were engaging with: mealtimes, office/school activities, and after work leisure. This section may be divided by subheadings. It should provide a concise and precise description of the experimental results, their interpretation as well as the experimental conclusions that can be drawn.

5.2. Interest Conflicts among Different Actors

Sidewalks are spaces that are expected to accommodate diversity and facilitate “unassimilated otherness” of the public [

53]. Due to this expectation, sidewalks are likely to be trouble-free and usually pleasant or convenient. Despite the demand of urban residents to interact with each other and the prospect of civility, it is at times unavoidable at specific spaces to get over competition and conflict. Especially in small public places, sidewalks showcase a continuous paradox. Apart from a basic function as a part of roadway, sidewalks are also claimed to help abutting spaces. Therefore, the coexistence of different activities can become a clash of interests. Over a specific time period, sidewalk occupants’ interests often conflict with the interests of other sidewalk users. The interests of street vendors and local residents or sidewalk users are a case in point. While local people and sidewalk users can enjoy a vibrant street life, they object to street vendors outside their house. Street vendors compete directly with local retailers by offering different products at a cheaper price. In addition, their activities may disrupt the flow of traffic and the smell of street foods disturb daily life. Nonetheless, both vendors and local residents or sidewalk users want busy—if different—sidewalks.

We assume that the minimum effective walking width of the sidewalk is 75 cm and the minimum effective width of the pavement is 90 cm. Therefore, the study used 90 cm width as the minimum criterion for the evaluation of continuous walking on sidewalks. Take the C1 segment as an example (

Figure 10), we illustrate a territorial map based on observations showing the range of the territories as each block represents an activity. We draw an imaginary pedestrian line in order to assess whether walking can be continued normally at different times of the day and use this to assess and highlight the barriers that may interfere with pedestrians. Based on the figure, the minimum utilization rate of sidewalk area, that is, the least to affect pedestrian movement time, is earlier or later, when high-density pedestrian behavior was not observed.

The result turned out that during daytime, this minimum space requirement was too neatly satisfied due to the space occupation of parking lot, mobile vendors. In contrast, from 17:00 onward with the peak at nighttime, the minimum space was severely violated by spaces for leisure and store spillover. Accordingly, even though the total area of peak activity in Nguyen Tri Phuong Street did not exceed 50% of the total pavement area, pedestrians would find it extremely hard to walk along the whole passage.

As above, we observed that the conditions of Nguyen Tri Phuong Street sidewalks were always affected by multiple factors. It seemed not appropriate for pedestrians to walk in an unobstructed environment, not to mention an enjoyment of walking. Therefore, it undoubtedly indicates that the sidewalk was created in a state of disorder which gave an impression that it was very difficult for walking without interruption.

6. Discussion

Sidewalks are strictly functional—for use in retail activities and movement [

54]. Therefore, sidewalks are one of the most important sources of employment and income for urban residents in developing countries [

17,

55]. However, by its presence and activities, the sidewalk informal economy, especially the sidewalk vendors, has been in conflict with city authorities on property for businesses, working conditions, sanitation, and licensing [

19,

56,

57]. Kumasi city authorities in Ghana, treat street vendors as causes of traffic jam and poor hygiene and sanitation, and their existence is perceived as ruining “the aesthetic quality of the urban settlements” [

58]. Comparably, Mexico City in Mexico, Santiago in Chile, and Mumbai in India also present street vendors as invasive encroachment, which hinders the modernization potential of cities to accomplish a global status [

21,

59,

60,

61]. However, some countries recently have changed their attitude to address this issue as urban governments try to promote economic benefits of street vendors [

17]. For example, people Bangkok city (Thailand) resorted to street vending stalls to earn their livings [

62]. Mexico City (Mexico observes that street vendors assist shop owners in selling goods on the street in place of shop owners, which would help to sell faster and more conveniently [

59]. These are evidences that when urban governments and the society in general regard street vendors positively, the city can still enhance social and economic benefits through business cooperation. Unfortunately, city regulators seem to overlook these advantages and miss out all the opportunities.

In Vietnam, sidewalks in many ways are one of the most important yet somewhat chaotic parts. On the functional side, sidewalks in Vietnam can be considered as inclusive spaces because people can express their attitudes, assert their claims, and use for their purposes within their spaces. Particularly, sidewalks in big cities can be divided into many types with various contributions to the citizens. Due to the sharp rise in vehicle ownership, urban planners assumed streets and sidewalks were inadequate, leading to excessive standards, which are imposed without much flexibility, compared with residential actual requirement. Therefore, it is necessary to have a new approach for sociable sidewalks to meet up the expectation of people’s real demands. As for the socio-economical features of Vietnamese urban life, there are three primary aspects that need to be rethought and encouraged to develop more: to promote neighborhood interaction; to contribute to street life, and to keep human and ecological health.

To promote neighborhood interaction. Conventionally in urban areas, sidewalks fundamentally serve the needs of a channel for movement of pedestrians. In addition, it is commonly thought in Vietnamese big cities that sidewalks function mainly for informal economic activities such as street vendors and guarded parking, while pedestrian movement rights are put aside. Sociable sidewalks, hence, must be able to change this traditional perspective. Sociable sidewalks aim to provide an environment for strongly promoting neighborhood interactions; at the same time, making a positive bonding between regional residents and temporary sidewalk users. This change, consequently, can make an economic and social return on investment to both local businesses and residents.

To contribute to street life. The exemplar of Nguyen Tri Phuong sidewalk in HCMC is a conclusive evidence of how the sidewalk is unavoidable in Vietnam street culture. Informal economic activities such as street vendors always have their own ways to keep thriving as they meet up the demand of the citizens so well. Even more, they add local color to the sidewalk’s life: they provide goods and services, they talk to the customers, they offer visual diversity, and so on. This is why more than any component, so as to make sidewalks more sociable, street vendors should be allowed and controlled in certain business areas where sidewalks are wide enough to accommodate their vending and still have space for pedestrians to walk freely.

Local and small businesses often run well because people welcome them for their uniqueness of goods and services style. In case of Vietnam, small business, such as local food stores, are even more welcome due to street culture. They often have more personalized and distinctive way of sidewalk encroachment to catch the attention of commuter buyers. Thus, these local businesses are a key to sociability on street sides. Therefore, once this key factor is well managed and kept in order, street side businesses can visually contribute at many levels to sociability.

To foster human and ecological health. Often in Vietnam, economic benefits are prioritized while the ecological system and human health are put behind. Visually, shades on the street with trees or canopies on the sidewalks are not given enough attention by both the authorities and residents, despite the hot and humid weather which could strongly affect food hygiene and people’s health. For this reason, human and ecological health are the bottom line in a new approach to make sociable sidewalks.

7. Conclusions

Sidewalks are fundamental parts wherever people live such that people can tell the dynamics of the cities from their sidewalks. However, sidewalks and their features can change in time as the cities are always evolving and reinventing themselves. In the context of Vietnam, sidewalks are usually associated with informal economic activities such as food vendors and sidewalks encroachment, particularly the guarded parking. This paper used behavioral mapping and photographing methods to give evidences that Vietnam sidewalks are not appropriate for continuous walking, not to mention enjoyability.

As a result, empirical evidence shown that sidewalks in Vietnamese big cities should be considered as inclusive spaces since citizens have always tried to use them for their own purposes with acceptance from surrounding people. By the exemplar of Nguyen Tri Phuong Street in HCMC, it is revealed that small businesses connected with the street sides are unimpeachable, and all authorities can do is to keep them in order and promote their sociability by managing from a new perspective. In line with this, a concept of “sociable sidewalks” is rethought and integrated with the existing mixed-up sidewalks to catch up with modern urban street practice. Accordingly, this paper has suggested three primary aspects that need to be reassessed and developed to make sidewalks more sociable: to promote neighborhood interaction; to contribute to street life, and to keep human and ecological health.

In this study, since the observation was conducted on a segment of a typical street in HCMC, some parts of the results may be biased toward a certain part of the city. This might influence the accuracy of the research. Therefore, in order to more profoundly comprehend the phenomenon of sidewalks, in developing countries generally and in Vietnam specifically, another case of sidewalks should also be observed scientifically. A comparative study among the contexts of developing countries should be taken into consideration in further research. Additionally, to make further recommendations and evaluate the sociability of the sidewalk, it seems essential to develop an integrated sociability index.

It is believed that provided these aspects are well-examined and turned into practice, the sidewalks’ condition would be much further advanced. With sidewalks being one of the most important parts in urban planning, this paper hopes to have contributed to a more comprehensive understanding on sidewalks design and management in order to make sidewalks more sociable.