Abstract

Flamenco is an art born in and inextricably associated with Andalusia in the south of Spain. The purity, the feelings it transmits, and the originality of its expression have made it known worldwide and it has been declared an Intangible Cultural Heritage by the UNESCO. This declaration, combined with the Spain’s tourist boom in the last years, has transformed this exclusive art into an important tourist industry with all the entailing perils for its survival. By means of the Lean Canvas model, combined with a survey of a panel of flamenco experts (especially artists), this study analyzed the fundamental factors that are key to developing a tourism product that, while respectful of its essence, offers tourists a genuine and quality product.

JEL code:

A12; D19; O01; R10

1. Introduction

The public interest in art, history, and culture in general has led the tourism industry to recognize the potential market niche of cultural tourism. However, cultural tourism cannot compete with Spain’s sun and beach tourism. In 2016, for instance, 64.5 million of Spain’s 75 million foreign tourists were attracted by the sun and beach, while 9 million were drawn by cultural tourism [1]. Spain, nevertheless, offers varied cultural tourism of quantity and quality, with tangible and intangible resources including historical, artistic and architectural heritage, museums, gastronomy, handicrafts, folklore, etc. Moreover, cultural tourism also fosters encounters between different customs and populations, giving rise to cultural contact [2].

Tourism is an essential industry for certain countries [3]. In Spain alone, it generates 11.4% of all jobs and 11% of the gross domestic product [1]. Spain’s expected growth for tourism in 2019 is 1.2%, higher than the average of other sectors. Hence, cultural tourism in recent years has tended towards a more selective tourism that, properly managed, avoids damaging the environment or the image of the destination.

The greatest growth in cultural tourism derives from new market niches. Its expansion results in a differentiation of submarkets that develop articulated and sustainable offerings, generating benefits for local communities while driving the market as a whole. The offers relate to architecture [4], gastronomy [5], literature [6], creativity [7], film [8], wine [9], industry [10], urbanism [11], shopping [12], science [13], language [14], religion [15], and flamenco [16]. All of these categories have been the object of research by different authors [17].

The development of Spanish cultural tourism dates to the late 1990s when the Secretary of State for Tourism proposed the incorporation of cultural resources to diversify and deseasonalize tourism. Although Spain’s cultural wealth places it at the global forefront, it only captures a small share of the market and does not enjoy an image in accordance with its reality in foreign countries [18]. A basic factor explaining this weakness is the lack of conversion of its cultural resources into products fit for consumption, and it is affected by complications in cultural management, accessibility, advance planning, promotion, and lack of introduction into commercial channels.

New cultural tourism focuses on integrating production and consumption and increasing links between suppliers and consumers. Instead of passive consumption, cultural tourists demonstrate a proactive approach by actively participating in creating travel experiences. On the other hand, suppliers focus on close interaction with consumers and the co-creation of high-quality experiences [19], with flamenco as one of the segments where the international tourist is not merely a passive consumer, but an active player in Spanish culture in general, and in Andalusia in particular [20].

Our work aimed principally to obtain the opinion of a group of experts from the world of flamenco on the current situation of this art and on how to achieve sustainable development of flamenco tourism that reconciles the essence of the art form and the necessary economic development. The opinions of these experts are not usually heard by the public institutions responsible for the promotion of flamenco tourism. We sought to compile their improvement proposals and apply the Lean Canvas tool based on the Lean Startup methodology. The Lean Canvas divides its modules into two clearly differentiated blocks: one focused on the client, which in this particular case would be both national and international flamenco recipients, and another one focused on the product, where characteristics of the product as well as logistical requirements of its management, creation, and communication are incorporated, which in this case is about defining the requirements that flamenco art must meet in order to reach potential customers, as well as management requirements to achieve the greatest success.

2. Popular Musical Expressions as Modes of Cultural Tourism

There are many definitions of cultural tourism, yet a review of the many studies defining it and its significance is not the objective of this paper. We simply based this study of tourism and flamenco on the definition of cultural tourism by Richards and Munsters [21]:

“All movements of persons to specific cultural attractions, such as heritage sites, artistic and cultural manifestations, arts and drama outside their normal place of residence”.

Broadening this definition, the European Centre for Traditional and Regional Cultures (ECTARC) offers eight potential focal points of cultural tourism [22]:

- (a)

- archaeological sites and museums;

- (b)

- architecture (ruins, famous buildings, whole towns);

- (c)

- art, sculpture, crafts, galleries, festivals, events;

- (d)

- music and dance (classical, folk, contemporary);

- (e)

- drama (theatre, films, dramatists);

- (f)

- language and literature, tours, events;

- (g)

- religious festivals, pilgrimages;

- (h)

- complete (folk or primitive) cultures and sub-cultures.

As noted in Point (d), music and dance, in their classical or contemporary form in popular folklore, are elements available for tourists as fundamental elements of the local heritage [23,24]. Hence, certain destinations are unequivocally associated with popular music and dance (e.g., Cuba with salsa, Buenos Aires with tango, Bali with Balinese dance, and Rio de Janeiro with samba) [25]. However, unlike other cultural assets, music and dance are not mere elements of contemplation but are first-level resources that arouse emotions, allowing the tourist to actively and inclusively experience the local culture [24,26].

Additionally, in an era where the internet allows immediate worldwide access to music and dance, the offer of live music emotion is an important resource for managers of tourist heritage, as well as for private promoters of festivals, performances, hotels, etc. [26,27].

A broad debate, therefore, ensues regarding the authenticity of the tourist offerings and their representativeness of the local musical culture. This issue takes on more weight as folklore represents the patrimony and cultural heritage of a people where idiosyncratic historical, religious, and social elements of the culture are arcane to foreigners. Tourists will, therefore, hardly be able to feel emotions when partaking something for which they are not prepared [28]. This leads to suspicion as to the product’s authenticity, and to what degree the performance is adulterated and geared toward tourism [27,28,29].

The ability of the visitor to distinguish the authentic from the adulterated product designed specifically for the unwitting depends basically on the motivation leading to attendance. This paper based its classification of this type of motivation according to Bywater [29] and McKercher and Du Cros [30] as follows:

- Intentional Musical Tourist: deliberately attends a specific event and is usually knowledgeable of the culture from previous visits.

- Cultural–Musical Tourist: motivated to learn about a local culture through music and dance. Attendance probably is based on previously acquired information.

- Casual Musical Tourist: motivated in the broad sense, open to music and dance but lacking information or prior knowledge of events.

- Accidental Musical Tourist: motivation is not cultural and event attendance, often organized by a tour operator, takes place in hotels or restaurants.

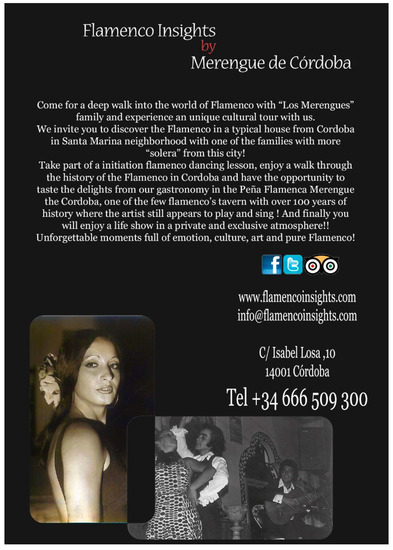

Hence, the degree of emotional implication, understanding of the event, and appreciation of the product will vary greatly as a function of the tourist type. Many innovative offers exist, as can be seen in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Avant-garde offer of flamenco. Source: Desirée Rodríguez, promoter.

The debate of authenticity has also been addressed from the perspective of the artists and researchers who report that economic dependence by local artists on tourism provokes a loss of the art’s essence. Moreover, it is obvious that offering an artistic style geared toward the uninitiated perverts its natural evolution, resulting in a less “pure” style driven by marketing [28]. Furthermore, initiatives of preservation, such as that of UNESCO declaring the dance Intangible Cultural Heritage, involve two serious dangers. The first is declaring a set of binding typological rules following criteria deriving from tangible cultural heritage [23,31]. The second is assigning responsibility for its protection to local, regional, or national authorities, following political criteria and not the needs of artists and promoting culture from marketing criteria instead of its intrinsic growth [27].

3. Flamenco: From Popular Music to Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity

Although the origins of flamenco are obscure, there is a consensus that its source is in Andalusia, a land that for centuries was a crossroads of Christian, Muslim, and Jewish faiths and different ethnicities, in particular the gypsy Stating that flamenco has an exclusively gypsy source is risky, especially considering that gypsies elsewhere did not develop this expression. Thus, interpreting flamenco as an expression of the cultural fusion in Andalusia is closer to reality [32].

Flamenco is a music and dance form transmitting emotions of love and heartbreak, joy and sorrow, struggle, reproach, vindication, and many others. It hails from farms, sierras, the countryside and sea, from miners and blacksmiths, and many other groups and places. It did not emerge to spawn a way of life, and much less to attract visitors. Hence, tourism has no link to its origins.

Its first artists date to the 18th century, with performances limited to private fiestas or celebrations [33]. “Cafés cantantes” where local artists sang, danced, and played the guitar emerged in the second half of the 19th century and ushered flamenco out of its isolation toward the masses. Artists dedicated themselves exclusively to their art for the first time without needing to practice other professions, and entrepreneurs beginning to focus on the flamenco.

The first years of the 20th century saw this art cross borders and reach a worldwide audience [34]. However, its real international emergence occurred in the 1960s, when tourists attracted to Spain’s sun and beaches (Andalusia, in particular), enthusiastically attended flamenco venues offering an authentic neo-romantic view of gypsies [35]. It must be noted that flamenco, at that time, was considered a marginal “low-life” art for a large sector of Spanish society.

It is not until the 1980s that the form was professionalized. An important factor was the creation of autonomous communities throughout Spain seeking to mark their own territorial identity after the fall of the Franco dictatorship [36].

Flamenco in Andalusia was institutionalized by Article 68 of its statutes:

“The Autonomous Community has the exclusive competence in the field of knowledge, conservation, research, instruction, promotion and diffusion of flamenco as a singular element of the Andalusian cultural heritage.”

This guaranteed its protection as any other tangible cultural asset, but also launched a debate as to the criteria defining it [37,38].

Within the 2004 strategy to institutionalize flamenco, Andalusian authorities presented several nominations to UNESCO, culminating in its being awarded in 2010 as Oral and Intangible Heritage of Humanity. Reception of this award, nevertheless, brought to light two serious problems. The first is the authority’s arrogation as its guarantor, as well as its means of preservation and diffusion [39]. This led to a struggle for hegemony between national and Andalusian authorities, as well as between artists and representatives of private companies [40].

Secondly, its award placed an even stronger international focus on the art, resulting in the emergence of public–private interests developing a distinctive flamenco brand as a symbol of tourism in both inside and outside Andalusia, where a link can be justified between the art and territory and culture [40].

Flamenco is an exponent of Andalusia’s cultural and historical essence, and has a strong appeal to the cultural tourist seeking a genuine emotional experience [20,41,42,43].

A tourist product is, in fact, an economic product, implying that a specific patrimonial or artistic resource is promoted to generate economic benefits for the local population and, potentially, for the country. There have been, however, few studies of the economic effects of flamenco tourism. The only institutional report carried out so far is that of the Junta de Andalucía in 2004, prior to the UNESCO award. Even so, that study evidenced impressive numbers: 625,000 flamenco tourists generating 542.96 million Euros. The growth in Andalusia, bolstered by the UNESCO award, likely led to a multiplication of these figures in recent years.

A great debate arises as to the negative effects that massive tourism has on an attraction and its environment, whether they be material (natural or architectural) or immaterial (like music), where the main risk when converted into tourist product is adulteration. This has led to concept of viable tourism.

This study intended to develop a business model through the Lean startup methodology to administer the marketing, logistics, costs, income, and contribution of value, and simultaneously balance the natural desire of promoters (public administrations, private promoters, artists, etc.) to develop flamenco tourism without distorting its purity. In this case, we aimed for the development of a product supported by the opinions of experts of the flamenco world, especially artists, with a final product aligned with the characteristics of sustainable tourism.

4. Materials and Methods

Osterwalder in The Business Model Generation [44], put forward the Business Model C anvas for startups as a means to outline hypotheses to initiate new enterprises or projects in the framework of an existing business. However, some experts have argued that the BMC fails to take into account certain critical aspects. Eric Ries [45] followed with the Lean Startup methodology for rapidly identifying conditions and attaining solutions with a minimized reaction time.

The Lean Startup methodology is based on the “build–measure–learn” or “action–reaction–adjustment” cycle, which eliminates all accessory elements from the process to quickly detect if the path is correct and, if not, to rectify it. In light of this methodology, and in response to this need, Ash Maurya [46] proposed the Lean Canvas tool.

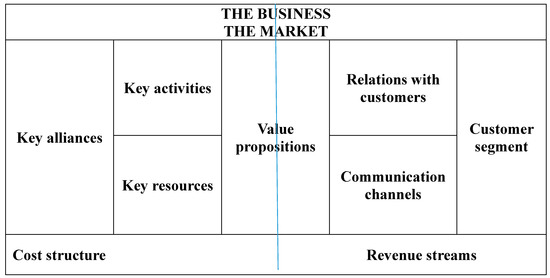

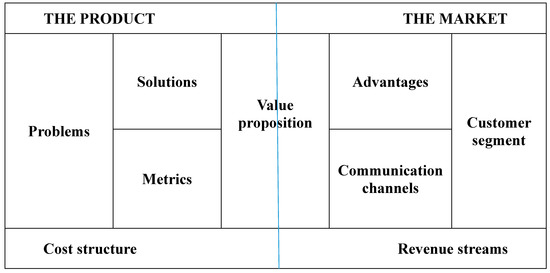

Figure 2; Figure 3 reveal the similarities and contrasts between the two canvases. The first, and most important, is that the BMC focuses on the market and business, while the Lean Canvas focuses on the market and the product.

Figure 2.

Business model canvas. Source: Javier Megias [47].

Figure 3.

Lean Canvas. Source: Javier Megias [48].

The modules common to both canvases are:

- the value proposition, indicating what is provided to the consumer;

- the customer, i.e., the segment to which the value is allocated;

- channels allowing communication with the customer;

- definition of revenues and cost structure.

The contrasting modules of the Lean Canvas are:

- in the market block, channels and customer relations are merged and a module is opened to define the advantages that are different from those of the competition;

- in the product block, the following modules are observed:

- ➢

- problems that the client presents replace the key alliances that are irrelevant in most startups,

- ➢

- solutions to the problems replace key activities,

- ➢

- metrics that validate hypotheses and eliminates key resources.

In order to minimize the build–measure–learn cycle, it is possible to dispense with the identification of key activities and resources, even if at a certain time it will be necessary to return to these tasks.

The current study was the first attempt to determine the perspectives of flamenco practitioners on the effects, benefits, and harms of its tourist value, especially since its Intangible Heritage of Humanity award, in order to develop a tourist product directed to public or private managers that is respectful of the art’s essence through a Lean Canvas model.

The genuine characteristics of the flamenco world and its practitioners, as well as the type of information obtained, indicated that a qualitative methodology was the most suitable means by which to attain the objectives of this research.

This therefore led to the choice of a survey of experts from the flamenco world. After selection, personalized interviews were carried out with a defined script open to non-directed comments. The interviews, most often face-to-face, were conducted by the researchers themselves. Some were also conducted via telephone or online questionnaire. The interviews were halted when the sampling attained 30, the saturation point of the data.

The experts were from different spheres of flamenco: public and private entrepreneurs, managers, writers, and artists. Some, such as the guitarist Vicente Amigo or the bailaora (dancer)/businesswoman Blanca del Rey, were recognized artists, while others were influential personalities.

The majority of respondents were men. It is certainly true that in the area of flamenco, men’s performance still predominates over that women. We might add that the association network itself, the flamenco rocks, were originally restricted-access and only men could enter.

Some of the interviewees belonged to several of the fields under study; for example, it is very common to find artists who in turn are entrepreneurs or representatives of other artists. With this premise in mind, we disaggregated the sample’s composition: the largest number of respondents were researchers, writers, or journalists, followed by artists; an important response was obtained from flamenco managers in public administration, located mainly in the Andalusian Institute of Flamenco; and finally, presidents of clubs, private entrepreneurs, and representatives of artists were also interviewed.

In general, data were obtained through a face-to-face interview, although some respondents were reached by telephone or through a survey via the Internet. However, live conversation had taken place previously with each of them.

The questionnaire consisted of 34 questions grouped into five blocks. Block 1: the respondent sociological profile; Block 2: personal opinions of flamenco and venues in general; Block 3: assessments of flamenco; Block 4: opinions on flamenco and tourism; Block 5: open questions regarding the key factors of the development of flamenco and flamenco tourism.

5. Results and Fashioning the Lean Canvas Tool

Flamenco, despite its relevance in cultural tourism, has not been scrutinized by the scientific community. Few researchers in Spain—or in Andalusia, defender of the art as its own—consider flamenco to be a dynamic element of cultural tourism [36,42]. The few existing studies have examined it from a panoramic perspective or from the point of view of the tourist [20,35,37,41,49]. Furthermore, the authors of the current paper did not identify any study that addressed the question of the vision, the positioning, and the propositions of action of flamenco as a phenomenon of cultural tourism from the art’s practitioners: artists and representatives who live from or for flamenco.

The sample comprised 30 participants, mostly men (76%), broken down into artists (23%), media professionals (13%), and peña (club) managers (40%) (about half from the public sector). The remaining 23% were researchers, scholars, and writers. Age ranged from 26 to 73 (average about 30), with about 30% between 40 and 49 and the same proportion older than 60. Participants up to 40 represented 20%, and the same proportion was between 50 and 59. Finally, 77% held university qualifications.

Applying the Lean Canvas Tool to Flamenco and Tourism

The product was flamenco and the customer was the tourist. The particularity is that the product is managed by both public and private institutions with the common goal of promoting flamenco. However, the means and channels are very different, and the product sometimes does not respond to what is really expected.

In the following section, we present the more outstanding elements of this business model in each of the Lean Canvas modules following the opinions of the experts. Given that the value proposition is in line with the market and the product, we first present the market values.

1. Value Propositions

Flamenco is an exclusive form of artistic expression involving the spectator through positive and negative passion.

The intentional musical tourist will gain more in-depth knowledge of the flamenco culture and instruction, and will develop a capacity of criticism.

The cultural musical tourist will learn about flamenco and differentiate it from other musical styles.

The casual musical tourist, although interested in culture in general, is not necessarily attracted to music and dance. Flamenco to these tourists can be a pleasant surprise, and witnessing an event can provoke emotions and development of a future bond with the art.

Finally, the accidental musical tourist will not particularly seek out culture, but will aspire to amusement through flamenco. Strategies targeted at this group require refinement due to the potential of capturing a new flamenco tourist.

2. Market

The clients defined above are:

- -

- intentional musical tourist,

- -

- cultural musical tourist,

- -

- casual musical tourist,

- -

- accidental musical tourist.

3. Channels

The tourist should receive quality information at the source/destination, along with an affordable and quality product from the standpoint of entertainment and instruction.

The Barometer of the Image of Spain by the Elcano Royal Institute [49] indicated that many countries, especially Japan, identify flamenco as a cultural image of Spain. In fact, when foreigners are asked to state a word evoking Spain, one of the most common is flamenco, preceded, generally, by bulls, sun, cities, and football. Hence, since foreigners possess an idea of flamenco, it is convenient to define the effective channels of communication.

Almost all collaborators, barring two, agreed on flamenco’s great presence on the Internet and especially in social networks. This is a fundamental factor for its diffusion among tourists for two reasons: First, because it allows an initial contact with the art without having to leave their country, and, secondly, once at the tourist destination, it allows them to identify where flamenco events are commonly offered and to have access to criticism of the events.

Communication with tourists, interested in flamenco or not, can therefore take place through the Internet. However, in the case of the uninterested tourist, it is essential to reinforce a personal relationship through agencies, hotels, and tourist offices that facilitate, encourage motivation, and promote the art in their own country.

Communication channels are fundamental to defining strategies that allow increasing tourism. It is thus necessary to contemplate, on one hand, the channels of diffusion, and on the other, the channels of supply.

It is also fundamental for the channels to define a joint marketing plan across all entities, following certain guidelines. There are, for example, private websites with agendas of flamenco events, websites often fed by the occasional arrival of information, or websites of clubs promoting their own shows.

Some interesting websites include the ones presented below, noting that none covers all of the flamenco experiences on offer, that the information largely comes from particular initiatives that want to publicize their events, and that shows in which the publishing institution is involved are included.

Junta de Andalucía website: this access does not include flamenco events in general, but does mention specific events [50].

Andalusian Institute of Flamenco website: this link leads to the website belonging to the Junta de Andalucía, mainly focused on events in which the institution itself participates [51].

Deflamenco website: open nationally and internationally, including large events that occur in main locations [52].

Guiaflama website: shows most representative national events and some from France [53].

Cordobaflamenca website: website that collects all the flamenco events that are communicated to it, focusing mainly on local events [54].

Large events of great prestige usually, in turn, have their own wide-ranging marketing plans. In the dissemination of flamenco events, the following channels are used, but it is important to make a coordination effort and, in all of them, the entire offer appears regardless of whether it is a public or private offer:

- -

- social networks,

- -

- specialized websites,

- -

- travel agencies (essential to planning a flamenco trip),

- -

- hotels (very important for making contact with undecided tourists),

- -

- tourist offices.

The events are mainly located in theatres, prestigious cultural public spaces such as courtyards in Córdoba, flamenco clubs, and private premises.

4. Advantages

Flamenco tourism offers the following advantages:

- a)

- Regarding the general tourism on offer in Spain:

- -

- Flamenco has a competitive advantage over the classic bull and sun offers, as it is not linked to any particular season.

- -

- Tourism marketing for representative cities can combine with flamenco. This notion is bolstered by the fact that many tourist cities are in Andalusia, and that most Spanish capitals maintain an outstanding flamenco culture.

- b)

- Regarding the tourist experience:

- -

- Flamenco is an unlimited experience—the more one delves into this world, the more one becomes involved.

- -

- Flamenco exists in harmony with other tourist attractions such as gastronomy and wine. Flamenco events can even take place at emblematic sites.

5. Revenue

Their main drawback regarding revenue is that many events are not advertised along rigorous lines. In private premises, entrance fees are collected, and are often linked to a minimal consumption. Venues can also be organized free of charge, in pre-paid venues or in theatres after purchasing a ticket. However, given the lack of regulations and accreditation certificates, how can a venue’s quality be confirmed? Is it based on whether there is an entrance fee or not? Given to the general consensus that a venue’s value is measured according to the curriculum or trajectory of the artist, just under half of the respondents believed that purchasing a ticket is not a guarantee of quality. There are, in fact, many high-level venues free of charge organized by peñas and public entities. However, 41% indicated that there is a link between an entrance fee and the value of the event.

At times, tourists cannot be certain of the quality of a performance. In these cases, it is advisable to establish quality certificates offering information as to whether the artists are new or experienced, and whether they are relevant or not in the artistic world. Moreover, the experts concurred that “free flamenco” venues are counterproductive and depreciate the art.

On other occasions, flamenco is offered as a complementary service without an entrance fee or other cost (Figure 4). This has given rise, in certain hotels, to events of unacceptable quality targeting uninitiated tourists. These “flamenco” events that are in fact not flamenco, but another dance genre present the unwitting tourist with an erroneous notion of the art.

Figure 4.

Flamenco in a restaurant. Source: Francisco de Dios, promoter.

On many occasions, a tourist’s first flamenco contact will be through shows offered by hotels. Currently there is also a proliferation of pubs offering small flamenco samples and traditional tablaos that attract larger scale tourism.

There is a wide range of opinion among experts over whether flamenco in hotels promotes flamenco and flamenco tourism. The opinion of its inclusion in pubs is even more negative. The expression "el flamenquito" has emerged in reference to a low-quality flamenco designed to entertain tourists. Promoters, obviously, are not in favor of lowering the quality of the form, which is not at odds with offering a show capable of reaching people with little expertise.

Nevertheless, 45% defended flamenco in hotels, whereas the same proportion were against it in pubs. These views reflect an eagerness to care for the quality of the art, as well as using hotels as a bridge to raise the level of demand for the aficionados. Along this line, 62% of the sample (vs. almost 30%) considered that the same rigor should be applied to free hotel venues as to those with an entrance fee.

In the case of theatres, the prices are set according to the level of the event.

Another obstacle is that artist earnings are often within the submerged economy, where it is much more difficult to control quality. These cases also reduce flamenco’s impact on economic statistics. The participants in general noted that this is detrimental to the sector. The artists themselves, nonetheless, differed in opinion, as working illegally leads to greater earnings.

There are also free venues organized by public entities that do not directly affect the income of the area, but indirectly attract tourism by increasing revenues of restaurants, shops, and hotels.

There are also subsidies explicitly earmarked for flamenco activities.

The fact that tax deductions have recently been changed to favor patronage has facilitated access to funding from both private and business patrons.

The global flamenco industry is made up of a wide, complex, and interrelated range of goods and services from different sectors (textiles, footwear, accessories, musical instruments, magazines and books, venues, instruction, and tourism) [55]. Flamenco, therefore, represents an important economic asset in terms of both industry and services. In the tourist sector, it attracts many tourists every year looking for exclusive venues and instruction (mainly dance and guitar), while others, although it is not their main target, desire to experience flamenco first-hand.

This paper therefore examined the opinions of experts on these subjects. Apart from three, all agreed that tourism is a pillar of flamenco’s economic development—even more so in Andalusia, flamenco’s source, and from where it has transcended internationally.

After describing the Lean Canvas modules associated with the market, the study completed the product’s modules.

6. Problems

If there is not a problem to solve or a necessity being met, a product has no use. Many businesses start by creating a product, and only when it is on the market do they detect that its demand is not what was expected. The product is then initiates its own end. So, why offer flamenco if no one needs it?

The Lean Startup methodology strives to avoid the fall of a project and accelerates recognition of the need to change course or swing the project’s initial idea.

The flamenco aficionado needs to increase his/her flamenco instruction and experience it in its place of origin.

The aficionado of music recognizes flamenco and has the need to distinguish its different styles.

The tourist who attends a venue feels the need to increase knowledge of everything typical of the area.

The debate of flamenco’s purity and authenticity is wide and not exclusively linked to tourist venues. Some experts favor preservation, while others back evolution and fusion with other styles. Around 70%, in fact, defended that its assimilation of elements of other cultures opens doors promoting flamenco tourism, yet there are still those that reject fusion and insist on protecting a pure line at all costs.

The tourist presents his/her problem or need, and the product has to respect the art, while its origin is not at odds with evolution and fusion.

7. Solutions

According to the experts, the following actions promote flamenco tourism while simultaneously attending to its needs:

a) Offering a closed program from the country of origin.

Tourists should only travel after contracting a closed flamenco program.

The debate is how to assure sufficient quality so as to dissipate the debate of authenticity.

Therefore, a need exists to regulate the use of the expression “espectáculo flamenco” and limit it exclusively to quality venues. Although most experts favored this notion, about a third objected to it. If this regulation were implemented, it is essential to determine the entity responsible for defining flamenco. An alternative is a quality certificate serving as a guarantee, especially for the uninitiated, of an unadulterated event offered by professionals. However, among the survey’s artists there was no clear consensus as to the method and the entity that should be responsible for managing the certificate.

Public managers, on the other hand, tended to favor adopting quality certificates. Their support and the diffusion of flamenco at an international level could encourage future visitors to experience the art and lead private institutions to sign contracts in the country of origin. Along these lines, Andalucia’s governing body created the Andalusian Institute of Flamenco, dedicated exclusively to this art and its dissemination, and to publicly and privately promoting it beyond Spanish borders. Examples are the festivals of Nîmes, Mont-de-Marsan, St. Petersburg, and Berlin, the "Viva España" festival in Moscow, and others in London, Miami, and New York.

b) Offering theoretical and/or practical instruction to bolster the experience.

In order for the flamenco on offer to be of lasting quality, it is fundamental that the young engage with this art through three of its aspects: song, dance, and guitar. The schools of dance and guitar have a youthful following, but cante (singing) is particular, as it is generally considered to be a gift at birth. However, more and more cante teachers are emerging, albeit most often devoid of a teaching methodology. Sixty-six percent of the respondents believed that young people today are less fond of flamenco than older generations. Opposing this notion is the resurgence of peñas and gatherings led by young people, whose events attract the 20 to 40 age range.

Music instruction with flamenco for children would bolster the permanence of this art. Trusting that flamenco will survive simply by transmission from parent to child is very optimistic. Flamenco as a base of Andalusian culture, as an expression of a way of life, and even as a literary culture, deserves to be part of the music curriculum of the educational system. It is logical that pupils learn their regional music, and the recognition by UNESCO of flamenco as Intangible Cultural Heritage since 2010 supports this notion. Although flamenco possesses many peculiarities and many areas of study, Andalusians should at least recognize its different styles. However, although about 50% of the survey believed that flamenco should be a school requirement, 38% said it should be a complementary course.

What cannot be denied is that flamenco serves as a gateway to tourism—could an increase in instruction in schools directly influence an increase in tourism? In principle, it would only affect the inhabitants of the zone. Nevertheless, 80% of those interviewed considered that its effects on tourism, although not short-term, would have direct and long-term repercussions. Every flamenco aficionado of an area would be versed in the standard of this art.

c) Offering routes linked to emblematic sites and gastronomy.

As indicated in the first pages of this paper, musical expression is one of many elements of culture. Although musical expression is valued per se, there is no doubt that music reaches its full meaning when framed within its own cultural environment. In this sense, offering a show in a hotel is not the same as one in the courtyard of an emblematic building or in a historical tablao. Gastronomy falls into the same line as flamenco, and has always been associated, among others, with Jerez or Montilla wines and tapas. Consuming such products in the correct environment generates a life experience completely different from witnessing an isolated venue [56].

This cultural symbiosis allows the defense of the flamenco brand from Andalusia, its place of origin, where all the above elements make real sense. Given the importance of this art today beyond Andalusia, and even beyond Spain, it was compelling to examine whether experts perceived a danger of Andalusia losing its place in the defense of this part of its own culture. The opinion was divided as to whether flamenco can be used outside its origin, as well as the risk that the form be used for purposes of tourism beyond its origin without concern for quality.

d) Offering flamenco in peñas open to tourism.

Peñas or clubs are cultural associations whose members maintain and promote flamenco’s three features. They organize scantly advertised periodical celebrations inviting a guest artist (singer, dancer, or guitarist) to events witnessed solely by the club’s partners.

Although some, at times, offer special events to a greater public accompanied by lectures and/or training workshops, most simply focus on the local public. It is also customary for these events to be financed in part by local municipalities or by larger public institutions such as the Junta de Andalucía.

These type of venues, in fact, would benefit from greater advertising and openness to tourism that could serve to finance the association/club. However, peña members are usually purists that fear tourism as intrusive with negative repercussions. This attitude, however, is annulled as the great flamenco events are attracting more and more tourists who respect, learn, and admire the art.

e) Offering great events with intensive periodic presence (e.g., festivals of “La Noche Blanca de Flamenco” of Córdoba, “La Bienal” of Seville, etc.)

This type of offer is already taking place, with a great tourist presence echoed even by the media.

Great events are an offer well known to the intentional musical tourist, as this group, as seen from statistics, returns year to year. Informing the other types of tourists identified in this article will require more effort through advertising.

There are also prestigious events with a long tradition such as the National Contest of Flamenco Art of Córdoba, the prize-winners of which received top-ratings. However, the managers of this event have not relaunched it wholeheartedly, so it currently does not have the bearing it deserves.

When the Córdoba contest was initiated, flamenco artists were still considered “low-life”. Fortunately, this tag no longer remains, as 62% of those surveyed disagreed with it. Professional flamenco artists are in fact resentful of the wealthy class, which throughout history abused their services for their private parties.

All major flamenco events must have an impact proportional to what they offer, as it is a great opportunity for the art and, consequently, for the host area.

8. Metrics

Metrics allow the extent to which tourists are attracted to flamenco and what they pay for it to be determined. Megías [57] defined 10 fundamental metrics applicable to both private and public projects that ultimately serve to estimate flamenco’s macroeconomic level—that is, its total impact on the country’s economy.

The metrics are as follows:

- AQUISITION BY SOURCE: identifies the origin of potential tourists;

- ACTIVATION: measures the number of tourists interested in flamenco through a web that makes an offer compared to the number of tourists actually registered;

- RETENTION/ENGAGEMENT: quantifies how many times a tourist asks for a flamenco product;

- CHURN: measures the percentage of tourists interested in a flamenco offer that ultimately did not contract it (lost customers / initial customers) × 100;

- CONVERSION measures the percentage of potential flamenco clients (ACQUISITION) that purchased the product (MONETISATION);

- CUSTOMER ACQUISITION COST (CAC): relationship between the cost of acquiring, which includes all the expenses associated with making the product and reaching the client, and the number of tourists who purchased the offer;

- CUSTOMER LIFETIME VALUE (CLTV): gross benefit obtained from tourists during the time of consuming the product;

- QUOTIENT OF PROFITABILITY CAPTURE: CLTV (customer life cycle) / CAC (customer acquisition cost);

- CASH BURN RATE (CBR) refers to fixed monthly costs;

- REFERENCE: measures the relationship between the number of flamenco tourists attracted by other flamenco tourists and the number of new flamenco tourists.

9. The main costs are the following:

The cost of artists: it would be positive to clearly define artist earnings according to categories and avoid the current situation where some are paid undeclared gratifications well below a standard value, or, by contrast, paid from public resources amounts far beyond what certain artists routinely receive.

- -

- The cost of setting up the venue,

- -

- The cost of advertising,

- -

- Taxes.

Both artists and venues are subject to the general tax rate. Natural and juridical persons are levied a tax rate similar to that of any professional or profession. The increase of the value added tax (VAT) from 10 to 21% had a negative influence on all cultural activities. Fortunately, this tax returned to 10% in the 2017 budget.

It is clear that flamenco promotion requires quality control not only of the venues, but of instruction from infancy. It is also essential to encourage flamenco among young people, as well as to eliminate its links to the submerged economy. Granting tax benefits to entrepreneurs and companies financing flamenco is also essential. Around 50% of the experts responded negatively to this issue, while only 40% agreed.

Each of the modules cited above requires more detailed future study.

6. Conclusions

Cultural tourism is probably the oldest and most established form of tourism. Furthermore, it is so extensive that it continues to develop new niches. Musical tourism in the form of folklore is one of its most attractive forms, as it allows the tourist to take part in a culture that, until recently, was restricted to a small segment and inaccessible to tourists. Globalization has, in most cases, broken these barriers with a 180° shift, and this expression of folklore is now another element of the tourist attraction, which yields an increase of revenue for the local economy and artists.

As a result of this new dynamic, a wide debate has emerged regarding the authenticity of the flamenco venues offered to tourists, and the question of the adulteration the essence of the art for an uninitiated audience.

Flamenco has no clear origin. There is, however, no doubt of its roots in Andalusia, a region in southern Spain with a history of different cultures and ethnicities. As in the case of other arts, flamenco’s development as a tourist product was late and strongly linked to Spain’s tourist boom. A debate has nonetheless emerged questioning whether everything that is offered as flamenco is truly flamenco art, in particular when the venues are offered in hotels or pubs.

It is clear, therefore, that since the conversion of flamenco into a tourism product is unstoppable, the design of its offer must be sustainable: that is, driven by its artists as well as by those who live by and safeguard it, and that its future not remain exclusively in the hands of public or private managers guided exclusively by economic factors.

Since flamenco is a product with very particular characteristics and a great part of its demand comes from tourism, it is possible to frame it under a Lean Startup methodology which implies the launching of this product with a practical approach so as to detect errors that can serve to improve new releases. This ambitious approach requires sharing and coordination on the part of public and private organizers, striving toward a joint strategic plan.

From the public point of view, the most representative institution is the Andalusian Institute of Flamenco; therefore, it is considered that this body should lead the coordination and empowerment of all events and initiatives. We would recommend the existence of a strategic planning commission, in which the councilors of culture of the capitals of the Andalusian province, and the departments of culture of the most active Spanish towns in this area, Madrid, and Barcelona, as well as representatives of the following private groups: flamenco clubs, associations of flamenco artists, flamenco events with the greatest impact in each area, and the tourism sector.

Following consultations with experts, 250 suggestions for improvement were received, which, grouped and summarized according to Lean Canvas modules, could be classified as customer- or product-oriented improvements. On one hand, proposals were made for the improvement of flamenco as an artistic product in general, and on the other hand, suggestions were made for the improvement of flamenco as a tourist product.

The following is the plan based on the proposals that, according to the group of experts, should be coordinated by the strategic planning commission:

1. Proposals by experts regarding flamenco as an artistic product:

- Customer-oriented (according to Lean Canvas)

- -

- Support of public administrations;

- -

- Development of the strategic plan and marketing plan of flamenco, online, offline, and presence in social networks;

- -

- Professional management in the planning and execution of shows;

- -

- Rewarding private initiatives to support flamenco;

- -

- External projection, internationalization.

- Product-oriented (according to Lean Canvas)

- -

- Promotion of the flamenco brand. Presence in artistic entities (conservatories, Royal Academy of Fine Arts, Instituto Cervantes, etc.);

- -

- Promotion of study and research;

- -

- Quality control;

- -

- Systematic training in all aspects of the form;

- -

- Support for flamenco clubs and artists’ associations; support for young flamenco artists.

Following the modules of the Lean Canvas and the opinions of flamenco experts, we conclude that it is essential to segment flamenco tourism to adjust to its needs, that communication using online channels is fundamental for attracting tourism, that it is important to offer packages including other regional cultural aspects, and that flamenco promotion must be of a high quality that will, in turn, progress as the instruction of those who offer and receive it improves.

If artists, public and private managers, journalists, and researchers participate in promoting flamenco, they will best be served by jointly developing a project based on a strategy from the perspective of collaboration, and the creation of a sustainable tourism product of quality in the medium and long term.

Author Contributions

M.G.M.V.d.l.T., S.M.L., J.M.A.-F. conceptualized the work and ideated the structure. They analyzed the literature, interpreted and curated the data, and wrote the manuscript. The authors read and revised the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Instituto Nacional de Estadística. Available online: http://www.ine.es (accessed on 3 May 2017).

- Lage, B.; Milone, P.C. Cultura, Lazer e Turismo. In Turismo em Análise; Universidade de São Paulo: Sao Paulo, Brazil, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Torre, A.; Scarborough, H. Reconsidering the estimation of the economic impact of cultural tourism. Tour. Manag. 2017, 59, 621–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feio, A.; Guedes, M.C. Architecture, tourism and sustainable development for the Douro region. Renew. Energy 2013, 49, 72–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cunha, S. Gastronomic tourism, a differential factor. Millenium-J. Educ. Technol. Health 2018, 2, 93–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, M.; Andersen, H.C. (Eds.) Literature and Tourism; Cengage Learning EMEA: Bonston, MA, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Ali, F.; Ryu, K.; Hussain, K. Influence of experiences on memories, satisfaction and behavioral intentions: A study of creative tourism. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2016, 33, 85–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolan, P.; Kearney, M. Exploring film tourism potential in Ireland: From Game of Thrones to Star Wars. Rev. Tur. Desenvolv. 2018, 1, 2149–2156. [Google Scholar]

- Bruwer, J.; Rueger-Muck, E. Wine tourism and hedonic experience: A motivation-based experiential view. Tour. Hosp. Res. 2018, 19, 488–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.S.; Kerr, D.; Chou, C.Y.; Ang, C. Business co-creation for service innovation in the hospitality and tourism industry. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2017, 29, 1522–1540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres, J.A. New urbanism, tourism and urban regeneration in Eastern Lisbon, Portugal. J. Urban Regen. Renew. 2016, 9, 283–294. [Google Scholar]

- Bar-Kołelis, D.; Wendt, J.A. Comparison of cross-border shopping tourism activities at the Polish and Romanian external borders of European Union. Geogr. Pol. 2018, 91, 113–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García, M.R.; Martines, O. Scientific tourism and future cities. Int. J. Sci. Manag. Tour. 2017, 3, 123–130. [Google Scholar]

- Redondo-Carretero, M.; Camarero-Izquierdo, C.; Gutiérrez-Arranz, A.; Rodríguez-Pinto, J. Language tourism destinations: A case study of motivations, perceived value and tourists’ expenditure. J. Cult. Econ. 2017, 41, 155–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohd, S. Possibilties of Pilgrimage Tourism–A Study of Popular Shrines of Pargana Kuthar in South Kashmir, Anantnag. Asian J. Res. Soc. Sci. Humanit. 2018, 8, 167–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez, L.; Fraiz, J.A.; Alén, E. El turismo cinematográfico como tipología emergente del turismo cultural. Pasos Revista de Turismo y Patrimonio Cultural 2014, 12, 159–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, T.T.; Camacho, D.; Jung, J.E. Identifying and ranking cultural heritage resources on geotagged social media for smart cultural tourism services. Pers. Ubiquitous Comput. 2017, 21, 267–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jimeno, M. El turismo cultural en la gestión de la marca España. Boletín Elcano 2005, 20, 41. [Google Scholar]

- Jovicic, D. Cultural tourism in the context of relations between mass and alternative tourism. Curr. Issues Tour. 2016, 19, 605–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aoyama, Y. The role of consumption and globalization in a cultural industry: The case of flamenco. Geoforum 2007, 38, 103–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richards, G.; Munsters, W. Cultural Tourism Research Methods, 2nd ed.; CAB International: Oxfordshire, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- ECTARC. Contribution to the Drafting of a Charter for Cultural Tourism; European Centre for Traditional and Regional Cultures: Llangollen, Wales, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Brandellero, A.; Janssen, S. Popular music as cultural heritage: Scoping out the field of practice. Int. J. Herit. Stud. 2014, 20, 224–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lashua, B.; Spracklen, K.; Long, P. Introduction to the special issue: Music and Tourism. Tour. Stud. 2014, 14, 3–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daniel, P. Tourism dance performances: Authenticity and creativity. Ann. Tour. Res. 1996, 23, 780–797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibson, C.; Connell, J. Music and Tourism: On the Road Again; Channel View Publications: Clevedon, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Stokes, M. Music, travel and tourism: An afterword. World Music 1999, 41, 141–155. [Google Scholar]

- Dunbar-Hall, P. Culture, Tourism and Cultural Tourism: Boundaries and frontiers in performances of Balinese music and dance. J. Intercult. Stud. 2001, 22, 173–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bywater, M. The market for cultural tourism in Europe. Travel Tour. Anal. 1993, 6, 30–46. [Google Scholar]

- McKercher, B.; Du Cros, H. Cultural Tourism: The Partnership between Tourism and Cultural Heritage Management; Routledge: London, UK, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Vecco, M. A definition of cultural heritage: From the tangible to the intangible. J. Cult. Herit. 2010, 11, 321–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruces, C. Historia del Flamenco: Siglo XXI; Tartessos: Sevilla, Spain, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Vergillos, J. Conocer el Flamenco: Sus Estilos, Su Historia; Signatura Ediciones: Sevilla, Spain, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Millán, G.; Millán, S.; Arjona, J.M. Análisis estratégico del flamenco como recurso turístico en Andalucía. Cuad. De Tur. 2016, 38, 297–321. [Google Scholar]

- Aoyama, Y. Artists, tourists, and the state: Cultural tourism and the Flamenco industry in Andalusia, Spain. Int. J. Urban Reg. Res. 2009, 33, 80–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortega, C. El Impacto del Flamenco en Las Industrias Culturales Andaluzas; Universidad Complutense de Madrid: Madrid, Spain, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Machin-Autenrieth, M. Flamenco ¿Algo Nuestro? (Something of ours?): Music, Regionalism and Political Geography in Andalusia, Spain. Ethnomusicol. Forum 2015, 24, 4–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Washabaugh, W. Flamenco Music and National Identity in Spain; Ashgate Publishing Limited: Surrey, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Bortolotto, C. La problemática del patrimonio cultural inmaterial. Cult. Rev. De Gestión Cult. 2014, 1, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruces, C. El flamenco como constructo patrimonial: Representaciones sociales y aproximaciones metodológicas. PASOS Revista de Turismo y Patrimonio Cultural 2014, 12, 819–835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matteucci, X.; Filep, S. Eudaimonic tourist experiences: The case of flamenco. Leis. Stuidies 2017, 36, 39–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thimm, T. The Flamenco Factor in Destination Marketing: Interdependencies of Creative Industries and Tourism-The case of Seville. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2014, 31, 576–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vidal, M. Intangible heritage tourism and identity. Tour. Manag. 2008, 29, 807–810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osterwalde, A.; Pigneur, Y. Generación de Modelos de Negocio; Deusto S. A. Ediciones: Bilbao, Spain, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Ries, E. The Lean Startup; Deusto S. A. Ediciones: Bilbao, Spain, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Megías, J. Las 10 Métricas Claves de Una Startup. Available online: http://javiermegias.com/blog/2013/05/metricas-startup-indicadores/ (accessed on 5 May 2017).

- Megías, J. Business Model Canvas. Available online: https://www.strategyzer.com/canvas/business-model-canvas (accessed on 5 May 2017).

- Megías, J. Lean Canvas. Available online: http://javiermegias.com/blog/2012/10/lean-canvas-lienzo-de-modelos-de-negocio-para-startups-emprendedores/ (accessed on 5 May 2017).

- Real Instituto Elcano (RIC). Barómetro de la imagen de España (BIE) 7ª Oleada, Resultados Febrero y Marzo; Elcano: Madrid, Spain, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Junta de Andalucía. Agenda cultural de Andalucía. Available online: https://www.juntadeandalucia.es/cultura/agendaculturaldeandalucia/eventos/todos/todos/Andaluc%C3%ADa%20Flamenca (accessed on 10 October 2019).

- Junta de Andalucía. Programas de Flamenco. Available online: https:// https://www.juntadeandalucia.es/organismos/culturaypatrimoniohistorico/areas/flamenco.html (accessed on 10 October 2019).

- Deflamenco. Agenda. Available online: https://www.deflamenco.com/ (accessed on 10 October 2019).

- Flama. Agenda. Available online: https://www.guiaflama.com/ (accessed on 10 October 2019).

- Guía Cultural del Flamenco de Córdoba. Agenda. Available online: https://cordobaflamenca.com/agenda/ (accessed on 10 October 2019).

- Molina, J.A. Relación entre el Turismo y el Crecimiento Económico en España. La Economía del Flamenco; Universidad de Sevilla: Sevilla, Spain, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Matteucci, X. Experiencing flamenco: An examination of a spiritual journey. In Tourist Experience and Fulfliment: Insights form Positive Psycology; Filep, S., Pearce, P., Eds.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Megías, J. Available online: http://javiermegias.com/blog/2012/09/entrevista-ash-maurya-running-lean-interview/ (accessed on 5 May 2017).

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).