Abstract

Gentrification, as a term introduced into China 20 years ago, has now become a topical word in scholarly discussion. This paper for the first time used the software of multiple pieces to analyze literature on gentrification between 1996 and 2017 in China based on bibliometrics, aiming to get the overview of the study, identify and expound the research themes, and analyze their evolution. It showed that the study on gentrification had entered into an exploratory stage with fluctuation from the early germination stage; gentrification research mainly concentrated on two disciplines, namely Geography and Urban and Rural Planning; the top 10 influential authors were identified and collaborative research teams leading the gentrification research had initially been formed. The themes of gentrification research in China were decided by visual analysis method, including urban renewal and dynamic mechanism of gentrification, evaluation and response to the effects of gentrification, new types of gentrification, and historical and cultural heritage conservation and creative industry, on which deeper content and information were described in detail. In terms of research themes evolution analysis, the results showed that the gentrification research in China had experienced the shift from initial concept and literature introduction to current empirical research and theory construction. There are significant signs showing the future trends of gentrification will move to the construction of a theoretical system of gentrification with Chinese characteristics, gentrification consequences evaluation and urban policies, new types of gentrification, gentrification driven by cultural consumption and authenticity protection of gentrification-stricken historical and cultural heritages, application of new technology to gentrification research, and relationship between shantytown renovation and gentrification in China. As to this paper, as far as the authors know, it is the first comprehensive systematic summary within this field based on bibliometric analysis.

1. Introduction

Glass [1], a well-known British sociologist, proposed the term “gentrification” for the first time to describe the process of the middle class flowing into the old residential areas of the low-income working class in inner city of London in 1964. It referred basically to both physical improvement and social stratum change in neighborhoods. The jargon was mired in controversy on the negatives and positives of gentrification as soon as it was put forth. Proponents argued that gentrification, as a form of spatial reconstruction, could create more socially mixed, less segregated, and more sustainable communities and neighbourhoods, which was accepted in policy circles [2,3]; Opponents believed that it could lead to community displacement for the lower income groups in gentrifying neighborhoods and destroy the sustainability of communities [4,5]. Both opposing views actually focus on whether gentrification is contributive to increasing urban sustainability or not, which reflects the fact that gentrification and urban sustainability have close connections to each other. The controversies on gentrification are essentially the issues of category of urban sustainability. An increasing number of researchers, for example Lees, L. [6] and Davidson, M. and Lees, L. [7] critically discussed the connections between urban sustainability policies and gentrification processes and put gentrification into the discussion of urban sustainability. Moreover, there exists an increasing convergence between urban sustainability policy and gentrification in practice [8]. Gentrification, marked with “green face”, is gradually embraced and promoted via trendy jargons like “liveability” and “sustainability” [9]. On account of its active effects on urban sustainability, gentrification has even gradually become a “global urban strategy” [10], adopted by many city governments.

In spite of the debates on the effects of gentrification, the fact that it then was observed more widely in developed countries, particularly in the UK and the US kept coming up. With the global geographical spread of gentrification, it begins to appear in developing countries as well, represented by China, South Africa, India, and Brazil [11]. So far, the effects of gentrification have expanded from developed countries to developing countries. Today, a growing number of cities around the world are promoting redevelopment efforts in inner city in order to combat inner city decline and explore sustainable development patterns, which can attract affluent residents to move into the inner city neighborhoods. These facts prove that countries in both global north and south have been affected by gentrification, exhibiting a global trend of this phenomenon [12]. It has become a global buzzword in the fields of urban geography, urban planning and urban society [13,14,15,16,17,18,19]. At present, the content of gentrification has been enriched as its phenomena appearing in different forms and diverse processes around the world [20], with the new concepts like “rural gentrification”, “new-build gentrification”, “super-gentrification”, “commercial gentrification”, “tourism gentrification”, and “studentification” [21,22,23,24,25,26,27], going beyond the initial meaning of classic gentrification [1].

Since the 1990s, a large number of cities in China have been undergoing urban renewal. Against this background, Chinese linguistic scholar Jin [28] introduced the concept of gentrification into China for the first time in 1993. She distinguished the connotative difference of “gentrification” and “renovation” to demonstrate the specific meaning of “gentrification” in succession of social stratification and improvement of built environment, while the respective Chinese word and entry were not included in her study. In 1996, Zhou and Xu [29] mentioned this phenomenon when conducting a research progress review on residential mobility in western countries, and officially introduced the concept of gentrification to China’s urban research for the first time. They named it as “Shenshi-fication” (shenshi means gentry in Chinese), but failed to further discuss this phenomenon. Until 1999, Xue [30] comprehensively introduced the concept, causes, developing process and effects of gentrification in western countries, and discussed its effects on China. In 2000, Meng [31] and Sun [32] both called gentrification as “Zhongchanjieceng-fication” (zhongchanjieceng means middle class in Chinese). Since then, both of the two expressions can be seen in the gentrification literature in China. There are mainly two reasons for that: firstly, strictly speaking, there exists no such group that can be regarded as “gentry” in the class component of Chinese modern society seriously [33] and placed between bureaucrats and the common people, it was just ever a unique social class produced by the royal examination system in the traditional and ancient Chinese social structure [34]; Secondly, there is no uniform definition for the middle class so far in China, therefore, the worry is that the theory of middle class will contradict China’s political system [35,36]. As a result, officials in China call the group “medium income group” instead of “middle class” and the discussions on middle class mainly exist in the folk and academia. The divergence in translation of the term “gentrification” indicates a common problem, a difference in understanding of imported concepts, in the process of localization of western theories in China. This story is in fact a sign mirroring the controversies in gentrification research in China. Furthermore, gentrification often involves inequitable development in addition to its positive effects [37], and it has provoked considerable debates and controversies about its effects [38], therefore usually appearing as a negative concept in China. Despite these controversies, Chinese scholars did not stop embracing gentrification.

Since gentrification was introduced into China by the above scholars, Zhu et al. [39] conducted the first empirical research of China’s gentrification in Nanjing as an example in 2004. After that, researchers such as Zhao et al. [40] and He et al. [41] brought in other types of gentrification; researchers such as Xu et al. [42], Bian et al. [43], Song [44,45], and Chen [46] summarized the processes of western gentrification research with different perspectives; researchers such as Wu [47], Wu and Liu [48], He and Liu [49], and Song et al. [50] made a positive contribution to the construction of Chinese gentrification theory. In general, the academia in China studied gentrification from four aspects, namely, concept introduction, empirical research, literature review, and theoretic research [51], and has made much progress through consensus and disputes. Currently, the size of China’s middle class has been increasingly growing, and urban renewal has also been promoted with unprecedented efforts. For instance, state-led shantytown renovation projects, aimed at improving people’s living conditions, perfecting urban functions, and improving urban environment, have completed 18 million renovations of shanty towns nationwide in 2015–2017. In 2018–2020, 15 million shanty towns will be renovated. It indicates that the phenomenon of gentrification is becoming a crucial part of future reconstruction of China’s urban space [52]. Undoubtedly, China will play an important role in the international gentrification research. To promote China’s gentrification research, it is necessary to unify the Chinese names and conceptions of gentrification. In 2016, Zhu [53] rearranged the concept and connotation of gentrification based on China’s political, economic and cultural environment, and named it as “zhongchan-fication”. He avoided “class”—a sensitive political word to make more Chinese people accept the concept of gentrification. Zhu, X.G. convened an international academic conference in China for the first time in December of 2017 to discuss the concept and definition of “gentrification”, together with many scholars, such as, Smith, D., Zhou, X., Wu, Q., et al. They generally accepted the concept and launched “Nanjing University Declaration in the First Forum of China’s Gentrification” to positively promote the integration of Chinese gentrification research with international gentrification.

Gentrification research in China sticks to the strategies of “bringing in” and “going out”. Some scholars also have published their research outcomes in international academic journals. He [54,55,56,57] conducted research on State-sponsored Gentrification, a special form of gentrification with strong Chinese political, economic and cultural characteristics, and discussed new-build gentrification in central Shanghai and two waves of gentrification in Guangzhou. Song and Zhu [58] analyzed the political and economic environments of urban gentrification in China, then comparatively analyzed the characteristics of Chinese and western gentrification. The changes brought by the state-led urban redevelopment have exceeded the sporadic changes brought by a few middle-class people moving back to urban center in China [59]. Wu et al. [60,61,62] conducted empirical gentrification research in Nanjing, and found a special and new form of gentrification, which was guided by high-quality educational resources in school districts of urban centers. They combined the Chinese word for education, “jiaoyu”, with the tail of the English word “gentrification” and created a new concept—“jiaoyufication”, attempting to analyze the mechanism and effect of social stratum differentiation and spatial differentiation in educational resources in school districts. Yang et al. [63] empirically revealed a socio-spatial transformation in the village of Xiamen City, China. They discussed the drivers of gentrification in rural China, and found that villagers with land ownership acted as landlords benefiting from gentrification, while grassroots artists and young people were at risk of displacement. Huang et al. [64] found that gentrifiers choosing to move to central Beijing were for the sake of improving and reproducing their spatial and cultural capitals, which differed from what happened in western metropolises. Compared with the number of papers published domestically, Chinese scholars published fewer papers in international journals, and westerners, consequently, have a limited understanding of Chinese gentrification.

Literature review is one of the most effective methods for western scholars to understand the progress and the trends of gentrification research in China. However, there are a few limitations existing in current gentrification literature reviews of China, mainly in Chinese. First, the content of literature reviews in China, like the research of Wu and Yin [65], Huang and Yang [66], and Xie and Chang [51], et al., owing to an early date of publication, did not cover the research outcomes in recent years. Second, there has been no systematic review of this field using bibliometric analysis so far. Qualitative description, adopted by current research reviews, has limitations in handling massive literature reviews and tends to be of strong subjectivity. Third, no literature review of China’s gentrification research in international academic journals has ever been published. Therefore, it is necessary to further conclude the process of gentrification research and analyze its development trends via literature review in time.

Differing from existing reviews, this paper conducted a bibliometric review based on the bibliometrics analysis that provides a method of visualizing detailed information about the research trajectory over time, offering certain advantages in gathering the objective information. The remainder of the paper is organized as follows. After the introduction, in the Section 2, it introduces initial data statistics and presents the research method. In the Section 3, it elaborates the results based on the methods of descriptive analysis and social network analysis. In the Section 4, it illustrates the results of research themes identification, research themes and their evolution analysis. In the Section 5, it discusses the findings and presents the future research directions for gentrification.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data Collection

China National Knowledge Infrastructure (CNKI) is an authority platform for China’s academic research and scientific decision-making, representing the overall situation of China’s research. Of all the periodicals, academic dissertations, and literature in conferences and newspapers in CNKI, the quality of periodicals indicates the overall level of research. Taking all those factors into consideration, this paper chose periodicals in CNKI as literature source. On March 21, 2018, we conducted document retrieval with the method of “advanced search”, the settings were as follows: literature type was “periodical”, search term was “subject”, and search word was “gentrification”, or with “studentification”, or with “jiaoyufication”. The time span was “1996–2017”, “source category” was “all periodicals”. The other system terms were default. It is noteworthy that the three search words above were converted to their counterparts in Chinese when we searched. We found 137 pieces of Chinese literature and kept 121 pieces after excluding some interview transcripts, newsletters, and literature that did not match our themes.

2.2. Bibliometric Analysis

Thanks to its advantages in the processing of massive literature, information extraction, and visualization research, bibliometric analysis is widely applied into the review research of different fields [67,68]. In this paper, we mainly adopted four pieces of software to conduct bibliometric analysis [69,70,71,72]. The first is Statistical Analysis Toolkit for Informetrics (SATI) version 3.2 software, released in 2012, which is a bibliographic information statistical analysis tool made in China. It can help data mining in literature and reveal features like the annual change rule of literature quantity, etc., and the distributions of periodicals. The second is the tool to analyze social network, University of California at Irvine NETwork (UCINET) version 6.212 software, released in 2012, which is a comprehensive package for the analysis of social networks. It can help us visualize the co-occurrence matrixes of both high-frequency authors and high-frequency key words generated by SATI, obtain a map of co-occurrence network, and thereby determine the most influential researchers in this field, their cooperation networks, and the general theme of research. The third is Statistical Product and Service Solutions (SPSS) version 22 software, released in 2013, which is a world’s leading statistical software in interactive, or batched, statistical analysis. With a strong function of multivariate statistical analysis, it can help us acquire dissimilarity matrix, based on the co-occurrence matrix of high-frequency key words. We can, thereby, conduct cluster analysis and multidimensional scaling analysis, which can further demonstrate the research themes and their relations of China’s gentrification research with visual method, and enable us to discuss the themes of China’s gentrification research with traditional literature review description methods. The fourth is CiteSpace version 4.0. R5 SE software. It can help us analyze the thematic trends over time based on the above cluster analysis and multidimensional scaling analysis.

3. Research Overview Based on Descriptive Analysis and Social Network Analysis

3.1. Time Distribution of Publications and Their Trends over Time

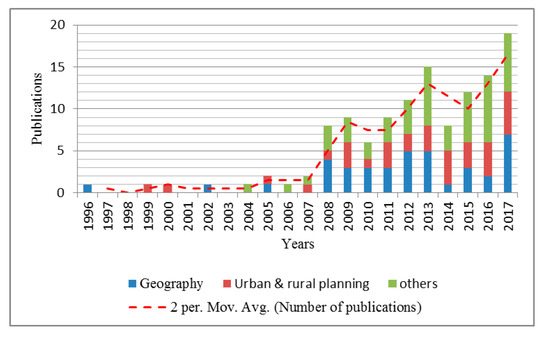

The analysis on the time distribution of gentrification publications and their trends over time helps grasp the current situation and trends of research. Therefore, we conducted statistical analysis on the results of China’s gentrification research. Figure 1 shows the annual publications from 1996 to 2017 and the frequency of gentrification across the Geography, Urban & Rural Planning (U&RP) and other journals. It is obvious that the quantity of publications in over 20 years exhibited an overall trend of “stable and slow development at first, and then growth with twists and turns”, which is consistent with the changing trend of the quantity of publications published in Geography and U&RP journals. Based on this trend, China’s gentrification research can be divided into two stages.

Figure 1.

The time distribution of gentrification publications and their trends over time.

3.1.1. Stage One: 1996–2007

This stage lasted 11 years, with intermittent publications and a relatively stable quantity. There were only 10 pieces of publications in this stage, accounting for 8.3% of the total. Less than one piece of work was published every year. It is noteworthy that seven out of the 10 pieces were published in the journals with the attribute of Geography and U&RP. It indicated that the research on gentrification had not received enough and wide attention and had just been led by the researchers in the field of Geography and U&RP at that time. It was the beginning of development with slow increase.

As we know, academic research in a certain area is usually closely associated with some important socio-economic phenomena and great events during the same period. In this stage, despite the increasing number of cities in urban renewal, gentrification still had not been the research hotspot. This could be because at that time urban development under the influence of urban growth supremacism was dominated by urban new construction projects that covered up urban redevelopment projects, and urban renewal projects presented the characteristic of single-point projects that had such little influence on urban society that they did not attract attention. Alternatively, it could just be because most scholars in the urban studies area were always focusing on physical space expansion instead of inventory space redevelopment and social space reconstruction and formed path dependence.

3.1.2. Stage Two: 2008–2017

Gentrification was gaining more and more attention with significantly accelerated development in publication quantity in this stage. Eight pieces of work, out of which five pieces were published in periodicals of Geography and U&RP, were published in 2008, which was significantly higher than that of the very year in stage one. A sudden increase in2008 indicated that a watershed came in 2008. It is necessary to analyze the causes of the sudden increase in the amount of literature in 2008. We speculated that the reason for the trend could be that under the impact of the global financial crisis from 2007 to 2009, and the constraints of control of land use, the shift of national economic strategy and urban policies occurred, and urban development experienced an overall shift from quantitative expansion to quality improvement. “Accelerating transformation” and “seeking breakthrough” became the themes of urban development in China from 2007 to 2008 [73]. Moreover, the global financial crisis prompted the Chinese government to work out a package plan with RMB 4 trillion (US $586 billion) 90% of which flowed to state-owned enterprises [74] and much of this was poured into real estate [75].

In addition, urban planning in China experienced the transformation, which was marked by the Comprehensive Plan of Shenzhen City (2010–2020) initially compiled in 2007, from increment planning to inventory planning aiming to optimize inventory space with the features of urban renewal, environment improvement, historical and cultural heritage conservation, urban village reconstruction, and shantytown renovation. Urban renewal, therefore, became an urgent demand at that time, and along with it came gentrification.

Since then, the number of publications has been increasing with obvious fluctuation, exhibiting the feature of “ten steps forward, one step backward”. It demonstrated that gentrification research in China was in an exploratory stage with fluctuation. For instance, literature quantity in 2010 and 2014 was significantly less than that in the previous years. The trend with some fluctuation was perfectly normal and was also associated with some important events. For example, shantytown renovation, an important form of urban renewal, got full-scale launch in 2010 and got further promoted by the State Council of China aiming to accelerate a new round of urban renewal in 2014. Regardless of the trend, however, the publications published in periodicals of Geography and U&RP accounted for around half of the total annual publications every year, which meant that gentrification research was concentrated in the Geography and U&RP area and gained attention from researchers in other fields at the same time.

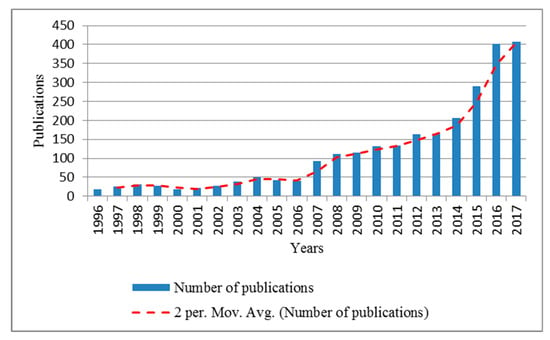

Figure 2 shows the annual publications of international gentrification research from 1996 to 2017 based on Web of Science. The literature quantity exhibited an overall trend of “stable and slow development at first, and then stable and apparent enough growth”. A distinctive feature of the trend with an obvious growth in the amount of literature in 2007, which will be more of a watershed, can be visually found. Interestingly, through comparison between Figure 1 and Figure 2, we found that although gentrification had only been introduced into China for more than 20 years, gentrification research in China was showing similarity in the overall global trend of this field in terms of the trend over the same period of time (1996–2017). Unlike the trend in Figure 2, there were some twists and turns after the watershed in Figure 1. In a word, gentrification research in China followed and lagged behind the overall global trend in gentrification.

Figure 2.

The time distribution of gentrification publications and their trends over time (based on Web of Science).

3.2. Periodicals Distribution of Publications and Disciplinarity Attribute of Research

Table 1 shows the publication distribution across the top 20 periodicals, and their disciplinary attribute and impact factors. After statistical analysis of the data from literature, it was found that 121 pieces of literature were published in 57 types of periodicals and there were 20 types of periodicals publishing two and more than two pieces of literature on gentrification. It should be noted that the top 20 periodicals published 84 papers, accounting for 69.4% of all the 121papers, and 75.0% of these 20 types of periodicals were our core periodicals. Even more remarkably, the top six periodicals publishing the most literature are Human Geography, Planners, Urban Planning International, Urban Studies, Urban Problems, and Progress in Geography, accounting for 60.7%. This means that gentrification research had become a hot topic in urban studies area and geography area in China. From the perspective of disciplinarity, an attribute of periodicals, the most periodicals in these 20 types of periodicals are of Geography and U&RP, exhibiting a disciplinary tendency towards these two fields. It is also noteworthy that the 20 types of periodicals have a relevant high factor of mixed influence in the above fields, but this factor does not have a positive correlation with publication volume.

Table 1.

Top 20 periodicals’ distribution of gentrification publications and their impact factors.

3.3. Influential Authors and Their Collaboration Network

Through the analysis on researchers’ information of these 121 pieces of literature, especially the number of researchers’ publications, citation frequencies, and the ratio of citations to publication, we could scientifically reveal and recognize the representative and influential researchers of the research on Chinese gentrification. Besides, the cooperative networks of these authors could be generated by means of conducting a social network analysis on high-frequency authors.

In order to identify the influential authors, we set “3 publications” to be the threshold and chose the option “Author” instead of “First author” through SATI software. We extracted 10 prolific authors in gentrification research. The setting not only ensures the integrity of researchers’ information, but also helps to conduct analysis on social networks of these authors in the next step. Meanwhile, we calculated their number of publications, citation frequencies and the ratio of citations to publications.

Table 2 shows the ranking of researchers by publications, citations and the ratio of citations to publications. In terms of the number of publications, Zhu, X. from Nanjing University, who published eight papers about gentrification, ranks the first, followed by Wu, Q. with 7 papers, Song, W. with seven papers, and He, S. with five papers. In addition, Qian, J., Sun, Q., Zhou, C., Huang, Z., Chen, P. and Hong, S. all published three papers about gentrification. All in all, these 10 researchers are all crucial for research of gentrification, and most of them are leading roles in this field. Most of them have a knowledge background in Geography and U&RP, which is also consistent with the result of the disciplinary analysis above. It can be assumed that the gentrification research in China exhibited a relevant significant aggregative phenomenon.

Table 2.

Top 10 researchers in terms of publications and their literature citations of gentrification.

According to the citation frequencies, scholars like Zhu, X., whose articles have been cited 220 times, still ranks the first, followed by He, S. with 138 citations, Wu, Q. with 86 citations, Qian, J. with 83 citations, and Song, W. with 68 citations. Articles of other researchers, for example, SUN, Q., Zhou, C., Huang, Z., Chen, P. and Hong, S., have been cited more than five times.

From the perspective of the ratio of citations to publications, articles that Qian, J., He, S. and Zhu, X. respectively published are on the top three, demonstrating that their articles have the most the average influence or popularity. It is notable that although Qian, J. ranks the first, all the three articles he published are all cooperated with He, S., and he is the co-senior author of these articles. In addition, although Sun, Q. and Zhou, C. only published three papers about this topic, their papers have been cited by copious literature. This is because the ratio of citations to publications of theirs reaches the top five. Wu, Q., who raised the concept of jiaoyufication, ranks the sixth. Although Song, W. published seven papers in this field, the ratio of citations to publications of his only ranks the seventh. One possible reason for this is that he is a young scholar in this field, and most of his works were published in recent years. Other researchers, for example Huang, Z., Chen, P. and Hong, S., are the last three in all three rankings.

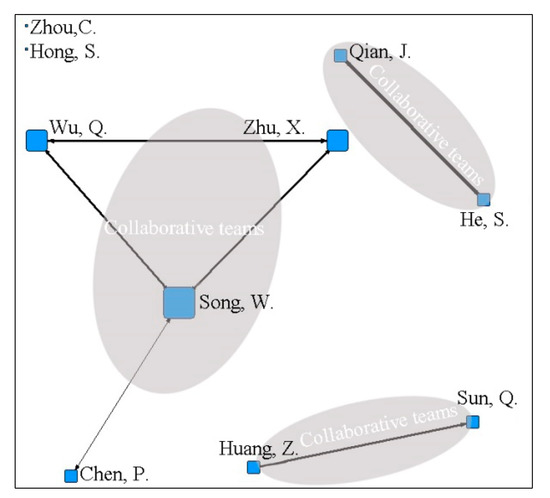

To better understand the research partnerships among the top 10 researchers, the collaboration network analysis is necessary. We therefore used SATI software to generate the co-occurrence matrix of high-frequency authors (see Table 3) and used UCINET software to visualize the social network of these authors based on the matrix, obtaining the collaboration networks.

Table 3.

The co-occurrence matrix of high-frequency authors by SATI.

Figure 3 shows the top 10 researchers’ collaboration networks of gentrification in China. That is to say that there are 10 nodes in the collaboration networks. The entire network is composed of three subgroups, including two single nodes. In Figure 3, a node represents an author, the size of which reflects the collaboration frequencies that this author studies with other authors. The larger the node is, the more co-authors the author has. Besides, a link between two nodes represents a publication co-authorship relationship between them. The thickness of line represents the intensity of cooperative relationships between researchers. The bolder the line is, the closer the cooperative relationship between two authors is. Song, W., Zhu, X., Wu, Q. and Chen, P., He, S. and Qian, J., and Sun, Q. and Huang, Z. have closer cooperative relationships. Zhou, C. and Hong, S., however, are relatively independent and do not have any cooperative relationships with the other eight authors. From this, it can be concluded that gentrification research in China has initially formed three collaborative research teams to explore gentrification. The scholars and their research teams mentioned above play a significant role in promoting gentrification research in China and enhancing the influence of gentrification research.

Figure 3.

Top 10 researchers’ collaboration networks of gentrification.

4. Research Themes and Their Evolution Analysis

4.1. Research Themes Identified by Visual Analysis Method

This section describes the three stages of research themes identification and analysis methodology. The first piece, high-frequency key words extraction, is described in Section 4.1.1. In this stage, high-frequency key words that represent the themes on some level are extracted by SATI software. The second piece, co-occurrence network analysis, is described in Section 4.1.2. Here, co-occurrence network analysis is then performed by UCINET software to get the inner connection of the high-frequency key words. Finally, the third step, multi statistical analysis, is described in Section 4.1.3. In this piece, the multi statistical analysis including cluster analysis and multidimensional scaling analysis is lastly conducted by SPSS software to classify the high-frequency key words and get the theme structure in two-dimensional space. The themes of gentrification research in China were deduced step by step from the first stage to the second stage and then the third stage. The three stages as well as the three pieces of software complement and reinforce each other in the process of identifying themes.

4.1.1. High-Frequency Key Words Extraction

Key words are the cores of the research papers, and high-frequency key words reflect the research themes in certain fields. Considering the limitation of key words, we conducted standardized pretreatment according to the following principles [76]:

- Merge the similar key words, such as, “original residents” and “original inhabitants”;

- Divide key words, such as, divide “the contrast between gentrification and the tendency to grass-roots” into “gentrification”, “the tendency to grass-roots” and “contrast”;

- Eliminate the key words that cannot reflect the real content of research, such as, “Huaqiao New Village”.

Then, we extracted 278 key words from bibliographic information by SATI software and sifted 31 high-frequency key words with the frequency no less than 3. Table 4 shows all the 31 high-frequency key words, demonstrated in the order of the numbers of times they appear in the literature. Higher frequency of the key words represents the higher attention that academia pays to them. These words, to a certain degree, reflect the themes of gentrification research in China. It can be seen from Table 4 that words, such as, “Gentrification”, “Urban renewal”, “Social space”, “Spatial differentiation”, “Effects”, “Rent gap theory”, “urban”, “Dynamic mechanism”, and “Urban redevelopment”, are all in the front. It can be assumed that gentrification in urban areas, the relationship between urban renewal and gentrification, the effect of gentrification, and the dynamic mechanism of gentrification are the important content in gentrification research in China.

Table 4.

Statistics of high-frequency key words of gentrification research.

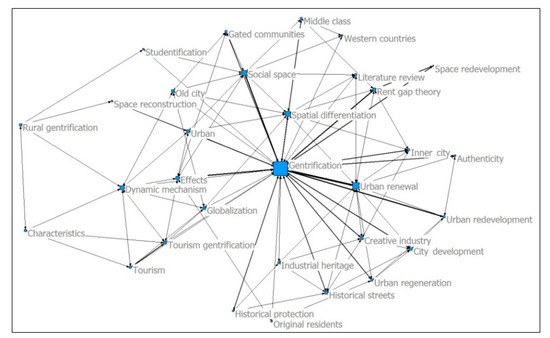

4.1.2. Co-Occurrence Network Analysis

High-frequency key words extracted above are relatively independent, and cannot fully reflect the inner connection of them. Thus, we adopted social network analysis to deal with this situation. First, we built a co-occurrence matrix of high-frequency key words of 31X31 by SATI software (see Table 5). The higher the frequency of two key words both emerging in one article indicates a closer relationship of the two. We then analyzed the co-occurrence network by “NetDraw” in UCINET software, and formed a complex and diverse network of relationship (see Figure 4). It can facilitate high-frequency key words to display the research theme. Each node in Figure 4 represents a key word. The larger the node is, the higher its central status is. The line between nodes represents co-occurrence relations. The bolder the line is, the higher frequency the co-occurrence emerges, the higher the intensity is. Key words in the core position gain more attention than those in the edge. For those in the edge, it may also represent an emerging direction for research. It can be estimated in Figure 4 that gentrification is in core position while spatial differentiation, urban renewal, social space, old city, and effects are in the sub-core position. Besides, rural gentrification, tourism gentrification, dynamic mechanism, historical protection, and authenticity are in the periphery.

Table 5.

The co-occurrence matrix of high-frequency key words by SATI (partly).

Figure 4.

The frequent keywords network.

4.1.3. Multi Statistical Analysis

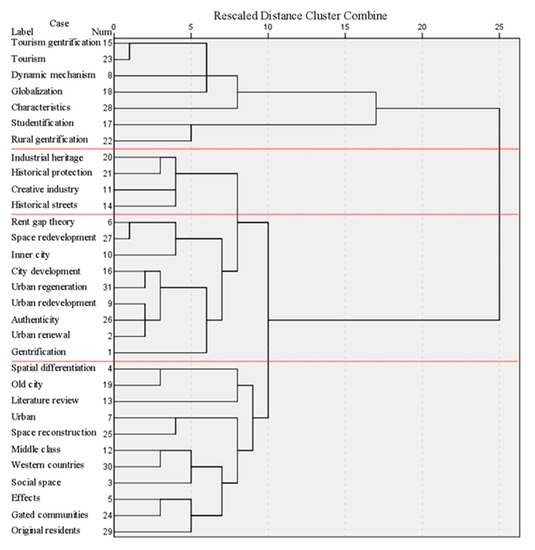

Co-occurrence network analysis cannot clearly classify key words, while cluster analysis can classify close key words according to their closeness [77]. We adopted the cluster analysis in SPSS software to explore the research with theme “gentrification”. Ochiia coefficient in SPSS software was adopted to transfer the above co-occurrence matrix into the relevant matrix (the figure is omitted). Since the value 0 frequently occurred in relevant matrix, which may amplify the errors, we finally used dissimilarity matrix instead of relevant matrix (the figure is omitted), as dissimilarity matrix is derived from the relevant matrix above, and it can avoid amplifying statistical errors. We conducted cluster analysis on dissimilarity matrix by system cluster command in SPSS software, and then acquired cluster tree (date structure) of high-frequency key words, and divided it into four categories (see Figure 5).

Figure 5.

The frequent keywords cluster analysis.

Compared with cluster analysis, multidimensional scaling analysis can more directly reflect the theme structure of certain fields in low-dimensional space [78], which virtualized the similarity of a series of complex conceptions and clustered the key words with close relations and relatively more similarities. We conducted two-dimensional scaling analysis on the above dissimilarity matrix by Euclidean distance model in SPSS software (see Figure 6). Results showed that Stress = 0.119, RSQ=0.961, exhibiting good degree of fitting, and presenting the academic connections between key words. In the figure, the key words distributing around the center are the directions which researchers in academic circles pay more attention to, and vice versa. Category cluster can be directly found in Figure 6, and the spatial distribution of key words based on similarity is generally consistent with the result of cluster analysis.

Figure 6.

The frequent keywords multidimensional scaling analysis.

According to the consistency of the co-occurrence network analysis and the result of multi statistical analysis of high-frequency key words, combined with the analysis of relevant theories, we generally divided gentrification research in China into the following four research topics:

- Urban renewal and dynamic mechanism of gentrification;

- Evaluation and response to the effects of gentrification;

- New types of gentrification;

- Historical and cultural heritage conservation and creative industry.

4.2. Research Themes Analysis

4.2.1. Urban Renewal and Dynamic Mechanism of Gentrification

Gentrification is a phenomenon of social space of social stratum substitution generally happening in the urban renewal at every level of urban system, thereby it is hard to discuss gentrification without considering urban renewal. Gentrification provides a new theoretical framework and tool for us to fully understand urban renewal which turns out to be a hot topic in urban renewal research [79,80]. The urban redevelopment, reconstruction of old city, update of inner city, shantytown renovation, urban village renovation, and other forms of spatial reconstruction are the embodiment of gentrification in urban renewal of China [81]. Gentrification in China started in 1978—the implementation of reform and opening-up policy. Promoted by multiple capitals and governments since the official implementation of housing marketization in 1988, gentrification has become a spatial phenomenon happening in many cities along with urban renewal. Significant differences exist between China’s and western gentrification in background conditions and stakeholders including subjects and objects of gentrification movement [31]. For instance, western gentrification took place in the period of re-urbanization, while the phenomenon in China appeared in the stage of centralized urbanization. Western urban renewals are mainly driven by the market of neoliberalism while ours are mostly driven by government with multiple subjects. The decay of old city is an inevitable topic and challenge for cities around the world. Gentrification focuses on the role of industrial upgrade and cultural factors in redevelopment of stock land, which is an important planning mode for urban renewal [82]. Gentrification research, therefore, focuses on the spatial reconstruction by gentrification in urban renewal. The relations between urban renewal and gentrification, especially the dynamic mechanism, are always unavoidable topics in gentrification research.

Scholars in China found the phenomena of gentrification in the process of urban renewal and renovation in many domestic cities, and had conducted numerous empirical and theoretical researches. Zhu et al. [39] found that gentrification had become a new phenomenon of urban social space in the process of urban renewal in Nanjing and was affecting the reconstruction of urban space. Song et al. [83] believed that gentrification along with the urban renewal in Nanjing had gone through three stages: breeding, emerging, and rapidly growth. Inner city of Nanjing went through two processes of gentrification: spatial function and social stratum [84]. The renovation of inner city was realized by gentrification. Meanwhile, urban renewal also promoted the development of gentrification in cities like Beijing, Shanghai, Guangzhou, and Shenzhen, etc. Xie et al. [51] believed that urban renewal might not always come along with gentrification, but gentrification was bound to appear in the process of urban renewal. In short, gentrification is a sufficient but not necessary condition for urban renewal. Recently researchers like Guo and Li [85] confirmed this. They found that the phenomena of gentrification—low-income original residents’ replacement by the migrated middle class—did not appear during Guangzhou Jinhua Street urban renewal.

Western scholars placed gentrification on both production-side and consumption-side or supply-side and demand-side, which has been adopted by a lot of Chinese research to explain the motivation mechanism of gentrification in urban renewal. On the production-side, researchers tend to explain gentrification in China with typical rent gap theory. Hong et al. [86] discussed the urban redevelopment from the perspective of rent gap. They believed that rent gap theory explained the root cause of gentrification from the supply-side, but it also needed certain improvements and amelioration based on our reality. Song et al. [50] drew on and revised rent gap model, proposing the content that suited the political and economic system in China. Based on the proposal, they discussed gentrification in Nanjing and analyzed the driving force of “rent gap”. Urban entrepreneurialism in China, represented by urban growth, has been continuing to rise in the context of China’s urban housing market reform beginning in 1998. More and more local governments manage and operate cities in the way of operating a business. Hong [87] believed that entrepreneurial local government, which has been influenced by urban entrepreneurialism in China, was involved in the distribution and competition of rent gap in the process of Chinese gentrification. He also believed that gentrification in China differed from the western countries in aspects like model, scale, and subject, etc., as gentrification in western countries was a creative process of destruction driven by capital. Profit-driven capitals led the gentrification in western countries, and capitals and powers drove China’s gentrification simultaneously [88]. From two perspectives of residents’ decision-making and developers’ decision-making, Ge et al. [89], based on rent gap theory, found the correlation between gentrification and a series of factors such as residents’ income, capital input of developers, and investment threshold, etc. They suggest that we can promote rational investment through regulations on investment threshold.

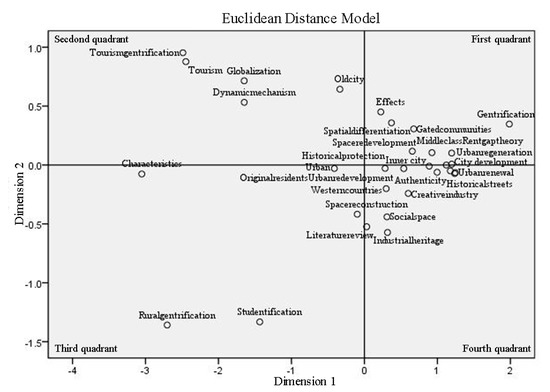

In short, rent gap theory provides an excellent analytical framework for interpreting the practice of gentrification in China from the perspective of supply-side theory and gets verified in practice. It is noteworthy that proper innovation and modification are made by Chinese scholars. In planning and construction practice, local governments try their best to take advantage of the “rent gap” to promote urban renewal in the inner city where the “rent gap” keeps widening. Figure 7 shows the distribution of demolition and construction plots and changes of land use between 2001 and 2011 in the inner city of Nanjing. It can be seen in Figure 7 that demolition and reconstruction was concentrated in north, south and center of the inner city of Nanjing where there existed low-level houses and low income groups. It can also be found that plenty of demolition plots, mainly residential land, were changed into land with high-end service industry and residence as their main functions. It indicated that there is a wide enough gap between the current rent and the potential rent. Moreover, the rent gap was expanded by governments through administrative means and rent jump came into being. This practice, driven by "rent gap", constantly promotes urban renewal and gentrification everywhere.

Figure 7.

The distribution of demolition and reconstruction plots and changes of land use between 2001 and 2011 in the inner city of Nanjing. (a) Before the demolition; (b) After the reconstruction. Source: A paper written by Song et al. [50].

Regarding the consumption-side, researchers tend to analyze how characteristics and cultural preference of the middle class affect migration from the perspective of culture and society. Academia has gradually accepted that cultural appeal throughout the city promotes the prevalence of gentrification in historical streets [90]. In post-industrial era, we should be aware that culture capacity can revise the dynamic mechanism of gentrification: Culture capacity has a significant influence on the process of socialization and spatialization of the middle class in the process of gentrification [91].

Chinese academia does not excessively rely on western theories of the production-side and the consumption-side, and therefore is not mired in the chatters and debates over dynamic mechanism of gentrification. On the contrary, they are relatively rational, diversified, and easily-accepted by scholars. It is universally believed that the difference in economic, political, social and cultural environments can cause a variation in mechanism and feature in gentrification in different countries and regions. The market has played a leading role in western gentrification and therefore the gentrification in western countries usually appears from the bottom to the top of the society. While gentrification in China is usually guided by government, so it usually presents a top-to-bottom model. The Chinese government promoted gentrification through land and housing reform, improvement in policy and environment, and allocation of resources, which was featured with government-led projects and the damage to the benefits of the low-income group [49]. With the background of globalization, the Chinese government usually participated in the process of spatial reconstruction, working with investors, financial institutions, and the middle class [83]. Huang and Yang [92] found in the empirical research of gentrification in Chengdu that policies, institutional innovation, adjustment of industrial structure, promotion of developers and self-will of residents all contribute to gentrification. Chen and He [93] found one type of bottom-up gentrification, which was led by individual investors, in certain communities of the old city in Guangzhou. It indicated that the bottom-up gentrification was not exclusive in western countries. The agent-based model of residential location showed that residents in the process of gentrification can be affected by both internal socioeconomic pressure and external forces when deciding their living environment [94].

4.2.2. Evaluation and Response to the Effects of Gentrification

Tiny changes in urban space can affect residents’ healthy lifestyle and urban sustainability [38]. As a relatively significant social phenomenon in urban renewal, gentrification, with its positive and negative effects, has gained more and more scholars’ attention. Sun and Huang [95,96], and Li [97] conducted research on gentrification and its influence in the Harlem and Soho areas of New York and inner cities of Canada to reveal the fact that gentrification had both positive and negative effects. Gentrification is like a double-edged sword, constantly affecting the improvement of the urban environment, stratum evolution, and residential differentiation, etc. [98]. The evaluation and response to gentrification effect has been widely discussed around the world.

The research on the negative effects of gentrification is similar both in China and western countries. The core questions that the research focused on include the differentiation of social space, peripheralization and displacement of original residents, the break of social network, the vanishing of traditional culture and damage of authenticity, etc. Xia and Zhu [99] discussed the negative influence of gentrification to low-income original residents in Nanjing, covering their daily life, employment, and commuting, etc. Because of urban gentrification, low-income original residents were usually forced to relocate to the city suburb and urban fringe, and could not get the desired jobs in their new places [100]. Although they may move to a better living environment than before, improvement is hardly observed in their living standard. The original social network also got wrecked [49]. Besides, it also caused “creative damage” to urban traditional culture [50]. Gentrification, together with urbanization, suburbanization, and marketization, accelerated differentiation of social space, and generated more of it [101]. For instance, to meet the demand of the increasing middle class during the gentrification, gated communities were widely favored by the capital during the urbanization [102]. Along with the emergence of gated communities and high-end apartments, the housing price in the old city that has conducted urban renewal projects kept growing. The middle class and high class gathered and low-income original residents were at high risk for displacement [50]. Before long, problems of social space differentiation emerged like residential segregation and poverty concentration, and it became difficult to maintain the residential rights of all social stratums [81]. The human settlements’ satisfaction of communities strongly differed between people of gentrifying communities and poor communities in the old city of Guangzhou, which reflected the polarization of social space differentiation [103]. Gentrification also struck and continuously broke down the original emotional relations of residents in the unit communities, which weakened the function of entity communities [104]. Wu et al. [105] found the phenomenon of jiaoyufication in school districts from the Community-level Census Data in 2000 just when they were analyzing differentiation of social space in the old city of Nanjing. Gentrification in the school district in China brought severe negative spatial effects and social risks [106]. He et al. [107] found that owing to unique land ownership and policies, which made indigenous villagers beneficiaries and promoters of rural gentrification movement through actively engaging in rent-seeking activities, rural gentrification mitigated the economic predicament of Xiaozhou Village, Guangzhou, and did not cause indigenous villagers to be displaced. However, displacement happened to the avant-garde artists due to rising housing costs along with the inflow of students. Similar results were also found in Cuandixia Village, Beijing by Zhang and Wang [108]. Authenticity, as the soul of sustainable community, was challenged during the globalization and gentrification [109]. Urban renewal in historical areas was often reduced to the means for capital to gain the benefits, and their authenticity was faced with great challenges. As a result, it always lost its soul [110].

For negative effects of gentrification, some scholars in China attempted to put forward different strategies to deal with it. For example, Xue [30] believed that government should carry out reasonable interventions on gentrification. Qiu [111] proposed that amendment should be made in the urban renewal mode, urban planning-making method and urban planning education system. He and Liu [49] proposed methods like perfecting public housing policy, supervising benefits-driven behaves of real estate developers and promoting public participation, etc., to deal with the impact of gentrification on residents forcibly removed. Gentrification promoted the living condition of Suzhou, meanwhile, it brought negative effects such as social structure differentiation, fragmentation of living space, and unbalanced development of public services. Wang and He [112], thereby, raised strategies like adjusting public resource, promoting mixed-income housing, and improving collaborative governance platform. It should be noted that social space differentiation like “over cluster of the poor” can be caused by public housing, despite its contribution to preventing the expansion of the negative effects of gentrification [113]. As for the unbalanced density of urban population caused by gentrification, Cheng [114] proposed to control residential density in order to deal with this spatial differentiation caused by varied urban population density. It is crucial to protect authenticity considering the damage of gentrification to physical and daily life authenticity. We should focus on the continuity of original residents’ daily life [110] to avoid being led in the wrong direction and thus becoming the target of overconsumption of government, capitalists and media. It is widely accepted to prevent the gentrification strike by economic and technological support [109].

The widely spread negative effects cannot shadow over the positive side of gentrification. More and more scholars in China have been aware of the positive effects of gentrification. As one of the most important forms for the reconstruction in Chinese cities during the transition period [101], gentrification, through reconstruction of spatial structure, has been constantly promoting the change in urban spatial structure and has improved environmental quality and land value [115], and enhances the quality of urban living standards [116]. It helps promote the process of urbanization and spatial reproduction [50], and efficiently prevents the further decay of urban center [117]. Zhang et al. [118] found that imposed gentrification and disorganized gentrification went against the sustainable development of local tourism, organized gentrification, however, it not only simply pursued the economic benefit, but also pursued the social benefit by providing original residents with employment settlement to maintain the original community and culture, which was advantageous to the sustainable development. Although various negative effects appear when original residents are forced to move, in recent years, state-led shantytown renovation has greatly promoted urban renewal in shrinking urban area. Original residents support this change due to its high monetarized settlement portion and high standard of money compensation, which brings noticeable benefits for them. Western countries have explicitly classified gentrification into urban developing strategy. However, controversies exist in regards to the positive and negative effects of gentrification, and it usually appears negative in China. Therefore, few cities in China list it in the urban public policy system. Luckily, recently academia gradually acknowledged the positive effects of gentrification and made efforts to promote it to be an urban development strategy. Song et al. [83] believed that gentrification, as a method to promote urban resuscitation, has contributed to increase economic value of construction area, improve urban environment and promote multiple culture. They believed that gentrification was gradually becoming welcomed by local government and capitalists in China. Li and Li [119] proposed that gentrification should be applied into areas, namely, old communities, urban villages, shanty towns and outer suburban districts in order to deal with problems existing in the cluster areas of the lower class. The positive effects of gentrification began to eliminate the negative effects in China [53].

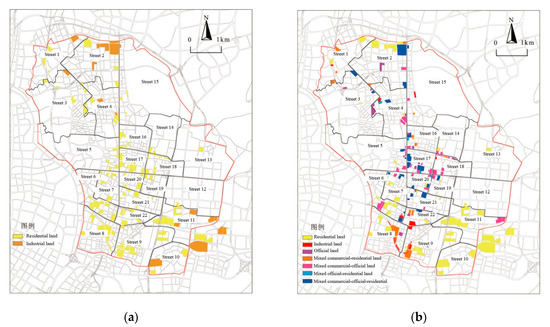

In practice, gentrification being applied to old communities, urban villages, shanty towns and outer suburban districts works really well. An increasing number of practices verify the active effects of gentrification. Figure 8 shows a village becoming gentrified. We found that there were some consumption places, such as coffee shops, that met the needs of the middle class, improved rural environmental quality and attracted many tourists, even foreign tourists. Before becoming gentrified, these places had been scenes of rural decay. At present, they have attracted not only the middle class but also original residents that had ever escaped from the village to return to the village.

Figure 8.

Image of rural gentrification in Bulao village, Nanjing, China. (a) The signboard pointing to a coffee shop; (b) Chinese and foreign tourists immersed in the village. Source: Authors’ survey.

4.2.3. New Types of Gentrification

Along with the global geographic expansion of gentrification, gentrification has spread from western countries to China and has become a multidimensional, complex process that affects different cities and regions in China as well as different levels of geographic space. From the east to west, from high-level core cities to low-level core cities, from cities to suburbs and rural areas, gentrification is now more often being observed everywhere in China. Along with the extension of the concept and connotation of gentrification, some new types of gentrification, based on classical gentrification, gradually came out and constantly evolved and spread in spatial geography and connotation. New types of gentrification were gradually brought by scholars in China and had been proved by empirical research one by one. Zhao et al. [40] were the first to bring the notion of tourism gentrification into China, and explained its concept, types and mechanisms. They believed that the aim of tourism gentrification research was the re-discussion on the cause of gentrification in China. After that, Zhao et al. [120] took the “Presidential Palace” area in Nanjing as an example and conducted empirical research on characteristics and factors of influence of tourism gentrification. For the gentrification effect generated by self-drive tour, Feng and Sha [121] extended and redefined tourism gentrification. According to the influence of stakeholders of tourism to tourist attractions and the following process, characteristics and effects of gentrification, Zhang et al. [118] divided this type of gentrification into three types: imposed, disorganized, and organized gentrification. He and Liu [49] initially introduced the concept “studentification” into urban research in China. Since then, He et al. [122] explained its concept, causes, spatial distribution, social influence and phenomenal evolution. Empirical research on studentification was also taken in Guangzhou. As is observed from the process of studentification research in western countries, both the empirical research and theory construction are in the exploratory stage [46]. So it is with China’s research on studentification. While discussing multiple types of gentrification in communities of Guangzhou, He et al. [41] found that traditional gentrification, new-build gentrification, and rural gentrification also emerged along with studentification. These four types of gentrification presented features different from the western countries. Because of the special social and economic background in China and the special land ownership policy, rural gentrification in China differed from Western rural gentrification in economic and material influence, relations between urbanization and rural gentrification, population substitute consequences, as well as the major players of the gentrification movement [107]. The differences between China and western countries, caused by institutions, systems, and policy, will definitely appear in both traditional and new types of gentrification. As for the causes of rural gentrification, Zhang and Jiang [123] supported the idea that migrated consumer demand guided the space production of the rural area during the boom of rural construction. They believed that the rural construction boom emerging in recent years was largely the result of capital investment in the rural built environment by surplus capital in the city. Furthermore, they believed that the surplus capital promoted rural space production in the form of rural construction to realize the process of continuous value-added and recycling of capital and drove the emergence of rural gentrification, providing a new path for rural resuscitation. However, from resilience perspective, Yan [124] made an assessment on two types of rural resuscitation—grassroots and rural gentrification. He believed that the tendency of grass-roots had more resilience and sustainability compared with gentrification in promoting rural resuscitation.

Chinese scholars have made positive attempts to introduce the new concept, new theory and study new phenomenon, meanwhile, they also make contributions to the construction of gentrification theory with local characteristics. Wu et al. [105], after long time investigations and analyses in school districts, put forward a type of gentrification full of Chinese characteristics—gentrification in school district. This is a new type of gentrification commonly taking place in large cities, which was caused by unbalanced allocation of educational resources. Wu [47], Wu and Liu [48] also attempted to bring gentrification of the peripheral new white-collar level and gentrification of female into the system of gentrification research to complement the theory system of gentrification.

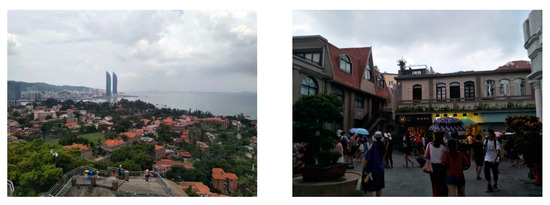

4.2.4. Historical and Cultural Heritage Protection and Creative Industry

Historical and cultural heritages, turning out to be an important carrier for urban renewal and resuscitation, had the potential to change urban development mode, promote urban image and realize urban sustainability. In addition, as an efficient tool for urban resuscitation, the protection and development of historical and cultural heritages, trying to meet the demand of the middle class, has become an important strategy to enhance urban competitiveness. Especially in the inner city, its unique historical culture and cultural symbol catered to the internal and external cultural consumption demands. Consequently, gentrification is promoted by cultural consumption here [125]. Abundant historical and cultural resources in the inner city constantly attract creative talents, bringing drivers of cultural capital for inner city resuscitation [126]. The creative class gathered in the inner city, which made the space environmentally diverse and open [127]. For instance, Gulangyu island in east China’s Fujian Province, well known for its varied architecture and multicultural history, had made efforts to be a “creative city” to cope with urban decay in the past few years, and it had brought certain gentrification in historical streets, which significantly enhanced the value of communities, and social and cultural development [128]. Gulangyu island was included on the UNESCO World Heritage list in 2017, which was tied to the strategy of “creative city”. The settlement of creative talents leads to the cluster of culturally creative industry for the inner city, and further attracts more of the middle class to cluster. It constantly changes the regional structure of social stratum, and finally generates gentrification [129]. Along with capital reinvestment and space redevelopment, creative talents and industries continuously cluster in inventory space like industrial heritage and historical and cultural districts, and then gentrification emerges. Gentrification can reduce negative effects of urban industrial heritage and rebuild a positive urban image. Therefore, western governments are promoting urban resuscitation via gentrification strategy [130]. Bologna “protects the house together with people in it” (integrated protection) [131], which has set an example for historical and cultural heritage protection in China. However, some research revealed that “Disneyfication” in landscapes easily tended to emerge during gentrification in historical streets [132,133], and cultural connotation in historical streets got distorted and lost its cultural value due to heavy commercialization [134]. Therefore, special attention should be paid to maintaining intangible cultural factors that are vulnerable to over gentrification in historical and cultural heritages [135]. Meanwhile, it is worth pondering the way of balance between culture and business values, short-term and long-term benefits, and public and private benefits. Zhang and Zhao [136] figured out two modes to protect and renovate historical streets when studying phenomenon and response to gentrification in historical streets: “driven by tourism and leisure industry” and “developed by high-end traditional housing”, both significantly guided by policy and promoted by economic globalization. They believed that measures like the guidance of public policy, direct participation of original residents and construction of security system should be adopted to maintain a stable social network and inherit intangible cultural heritages, and realize the comprehensive resuscitation of historical streets and the sustainability of famous historical and cultural cities.

At present, the areas with historical and cultural heritages such as historical and cultural districts, industrial heritages, traditional villages and so on have become the leading areas for the development of creative industry owing to abundant historical and cultural resources that just meet the needs of creative talents. Creative industry and creative talents stimulate the internal vigor of these areas and change social structure and housing markets. Many local governments, therefore, focus on these areas like Gulangyu in Xiamen (see Figure 9), Xintiandi in Shanghai and 798 Art District in Beijing in the process of urban renewal, while gentrification usually emerges in these areas.

Figure 9.

Image of historical streets gentrified in Gulangyu, Xiamen, China. Source: Authors’ survey.

4.3. Research Themes Evolution Analysis

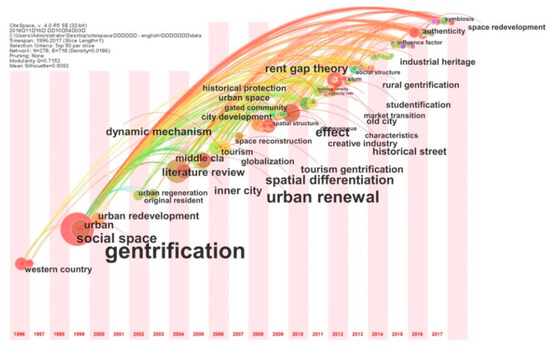

To conduct the time distribution and variation trends of word frequencies contributes to analyzing and understanding the research frontier and development trends of a certain field clearly. To reveal the evolution of research theme and understand the structure and developing trends of gentrification research in China, we therefore analyzed co-occurrence network of the 278 key words by CiteSpace software and displayed the result by “time zone” (see Figure 10).

Figure 10.

Trends of keywords of gentrification research in China.

Figure 10 shows the distribution of key words and their frequencies over time from 1996–2017. There are 278 nodes in Figure 10 and each node represents a key word, the size of which reflects the frequency of occurrence of a key word in 121 papers. The larger the node is, the higher the frequency of occurrence of a key word is. In addition, the nodes marked with white outer circles are nodes with higher centrality and they are more important in the knowledge network.

In terms of the frequencies of occurrence and the centrality of key words, key words including gentrification, social space, literature review, urban renewal, dynamic mechanism, middle class, inner city, spatial differentiation, effect, rent gap theory, tourism gentrification, studentification, rural gentrification, historical protection, industrial heritage and authenticity are prominent and remarkable, which is similar to the result in 4.1 and mirrors the research themes identification. Furthermore, it is remarkable that Figure 10 respects the trends of the themes. It is easy to note that authenticity, industrial heritage, slum, and new types of gentrification such as tourism gentrification, studentification and rural gentrification are newer research hotspots or seldom noticed.

It can be also found in Figure 10 that the number of key words started rising since 2008. It, to a certain degree, indicated that the number of results of gentrification research also gradually rose since 2008, which broke the slow developing condition of gentrification research before 2008. Based on this change, we divided gentrification research in China into two stages: 1996–2007 and 2008–2017, consistent with the result in 3.1. The results of Figure 10 are as follows: In 1996, the concept of gentrification in western countries, not in the form of keyword, was firstly introduced to the field of urban research in China, which started the gentrification research in China. In around 2000, key words including gentrification, urban, social space, urban redevelopment, urban regeneration, and so on appeared. Meanwhile, the concept of gentrification was introduced and described and revelatory discussions on it that might emerge along with the renovation of old city in China were also kept in progress. In around 2006, gentrification in urban renewal, one phenomenon of spatial reconstruction, made spatial differentiation a heated researching topic. The concept of tourism gentrification was brought and applied in empirical research, and soon so were other new types of gentrification. During this period, some gentrification research literature in western countries was introduced in China. In around 2010, the comprehensive evaluation on gentrification effects was widely expanded and the topic that creative industry contributed to gentrification in historical and cultural heritage protection received much attention from academia. In around 2013, the academia, combined with the condition in China and from the perspective of production-side and consumption-side, conducted much empirical research on gentrification in China, to analyze the phenomena, characteristics, mechanisms and effects, and tried to build a local theory of gentrification. In around 2016, the influence of gentrification on authenticity and original residents had received much attention. The term “jiaoyufication” with obvious Chinese characteristics was created under the background of unbalanced educational resources. The role rent gap theory played in explaining gentrification in redevelopment of the inner city was continuously discussed and endowed with Chinese characteristics.

In conclusion, gentrification research in China had gone through two significant changes i.e., from concept introduction and literature induction to theoretic review and empirical research and then to current stage with both empirical research and theory construction enjoying the same weight. Meanwhile, along with the extension of the concept and connotation of gentrification and the continuous increase of research results, literature reviews on the results of gentrification research both in China and western counties ran through the entire research process.

5. Conclusions and Discussion

5.1. Conclusions

Gentrification, as a global phenomenon, has become one of the important driving forces and tools to promote urban renewal, urban renaissance and urban sustainable development, due to which it is increasingly supported and encouraged by the government and developers in western countries. Although there is no city government that has definitely adopted it as an urban strategy in China so far, many governments actually have taken it in practice because they see more active effects of gentrification on preventing urban decline and promoting urban development. For example, gentrification can bring environmental improvement, an influx of middle class, and the promotion of space value, all of which provide power for urban sustainable development. Therefore, it helps to not only grasp its process and development trends but also to expand the scope of the issue to conduct literature reviews on gentrification research.

This study conducted a systematic literature review on gentrification in China based on 121 publications collected from CNKI through rigorous bibliometric analysis and traditional literature review description methods. The number of results had been significantly increasing for nearly a decade, demonstrating that gentrification had received rising attention in Chinese academia. Meanwhile, it showed that gentrification research in China had shifted from the early germination stage to an exploratory stage with fluctuation. Comparative analysis showed that gentrification research in China followed and fell behind the overall global trend in gentrification in terms of the trend over the same period. Most research results were published in periodicals with the disciplinarity attribute of Geography and U&RP, with a small amount in periodicals of architecture, tourism and multidisciplinary. Although gentrification research was categorized into a theme for multi-discipline researches internationally, it had played an important role of double discipline–Geography and U&RP in China. The results were mainly obtained by 10 Chinese researchers. It can be found through social network analysis that some researchers had close cooperation, exhibiting that gentrification research in China has broadly formed several collaborative research teams. Through various tools of bibliometric analysis, this paper scientifically visualized and identified the themes and evolution of gentrification research in China. The themes of research included urban renewal and dynamic mechanism of gentrification, evaluation and response to gentrification effect, new types of gentrification, historical and cultural heritage protection and creative industry. Though research focuses vary, their contents are relevant and continuous. As is seen from the analysis on the evolution of research theme, Chinese gentrification research has evolved from the initial introduction of concept and literature to the current empirical research and theory construction.

5.2. Future Research Directions

Several reflections for future research are raised based on the current understanding in this field.

First, there are significant differences between Chinese and Western gentrification in background conditions and stakeholders. As a result, it is impossible to comprehensively analyze the dynamic mechanism of gentrification in China with traditional theories featured with production-side and consumption-side. It demands more comparisons between research in China and western countries in the future. In addition, we should take the special economic, political and culture environments in China into consideration to carry out more empirical research, explore theories that can be applied into gentrification research in China, and build gentrification theory with Chinese characteristics.

Second, the academia in China has widely accepted the fact of gentrification and the existence of its positive and negative effects. However, they only carry out basic research, such as, phenomenon description, reason explanation and influence analysis. Although more and more results turn out to be consistent with the positive effects, many evaluations still focus on negative effects. Furthermore, little research focuses on how to utilize positive effects to alleviate negative effects. Meanwhile, few cities explicitly put forward strategies to apply the positive effects of gentrification into urban public policies just as the western cities do. In these cities, the local government regarded gentrification as an effective strategy to restore the image of shrinking cities, which gradually became a trend to fight urban shrinkage for local strategies. Besides, urban renewal of China emphasizes the compensation for ownership of real estate. From an economic perspective, all the original residents and homeowners can acquire considerable monetary compensation and property resettlement. However, renters may be forced to migrate because of the gentrification-driven rise in renting prices. As a result, we should conduct dynamic monitoring, assess the influence of gentrification on different social groups and deepen the effect evaluation of gentrification. Besides, we should do research that combines urban policies and deepens the mechanism of response and application to gentrification effect.

Third, along with the global geographic expansion of gentrification, gentrification emerges in cities at different levels in China, and even expands to the peripherical area of city, suburb area, and rural area. Cities at different levels may see gentrification during urban renewal, not only in the urban central area depicted by traditional gentrification. In this context, some new types of gentrification are introduced to China with the perspectives like feature, mechanism, process and effect. Nevertheless, new types of gentrification have not received enough attention, which demands further introduction and empirical research to enrich the gentrification research system of China.

Fourth, inventory space, like historical areas and streets, due to its abundant history and culture, suits the consumption preference of the middle class. Creative industry driven by cultural consumption and capital input are promoting the process of gentrification, which, as an emerging phenomenon, is a relatively emerging theme for gentrification research in China, demonstrating the universal applicability in consumption-side theory. However, we should not ignore the negative effects of gentrification on the authenticity of inventory space and the research on authenticity protection should be strengthened in the future.

Fifth, there are four research themes to demonstrate the results in gentrification research of China, but their most outcomes are obtained by qualitative research. Therefore, results are often acquired by theoretical speculation, theoretical demonstration, judgement based on experience and feeling, or simple data analysis, which lacks data to support. Methods of quantitative analysis like factorial ecology approach, multiple regression analysis, and cluster analysis, which have been widely adopted in the gentrification research in western countries, were hardly seen in China. Besides, new technology like big data has not been widely adopted in China’s gentrification research.

Sixth, recently, state-led shantytown renovation aiming to renew poor space such as shantytowns and slums has become an important type of urban renewal in China. However, policies for shantytown renovation in China are significantly different from traditional policies for urban renewal in key actors applicable and implementation mode. Therefore, the formation, feature, and effect of gentrification vary a lot. Currently, gentrification research in China mainly focuses on the relations between urban renewal and gentrification, and few carry out research on the relations between shantytown renovation and gentrification. However, the latter should be focused on in the near future.

5.3. Limitations