Toward Sustainable Schools: A Mixed Methods Approach to Investigating Distributed Leadership, Organizational Happiness, and Quality of Work Life in Preschools

Abstract

1. Introduction

- (1)

- Do school administrators’ distributed leadership characteristics predict teachers’ organizational happiness and quality of work life?

- (2)

- Is there a mediating effect of the organizational happiness of teachers on the relation between the school administrators’ distributed leadership characteristics and teachers’ quality of work life?

- (3)

- What are school administrators’ thoughts on the effects of their behaviors on organizational happiness and quality of work life of teachers?

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Universe, Sample, and Study Group

2.2. Data Collection Tools and Data Collection

2.3. Validity and Reliability

2.4. Data Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Quantitative Findings

3.1.1. Descriptive Statistics and Inter-Variable Relationships

3.1.2. Reliability

3.1.3. Structural Equation Modeling

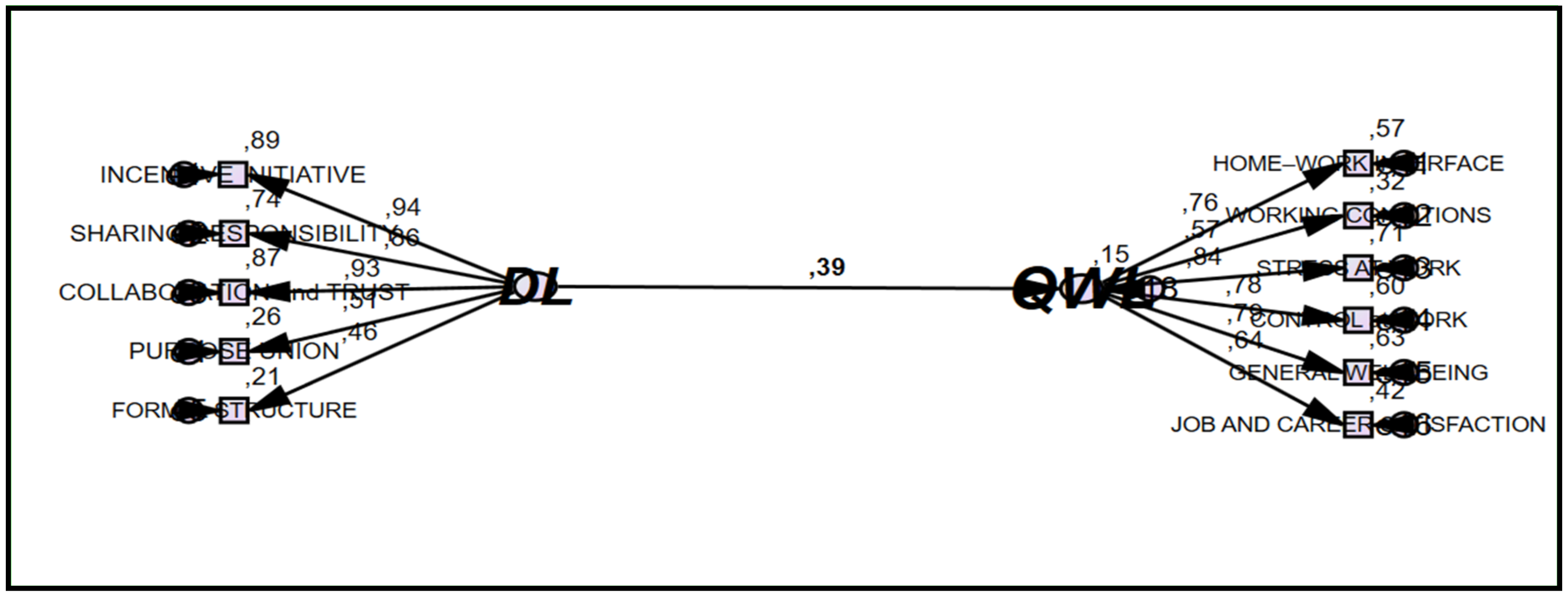

Testing Measurement Models

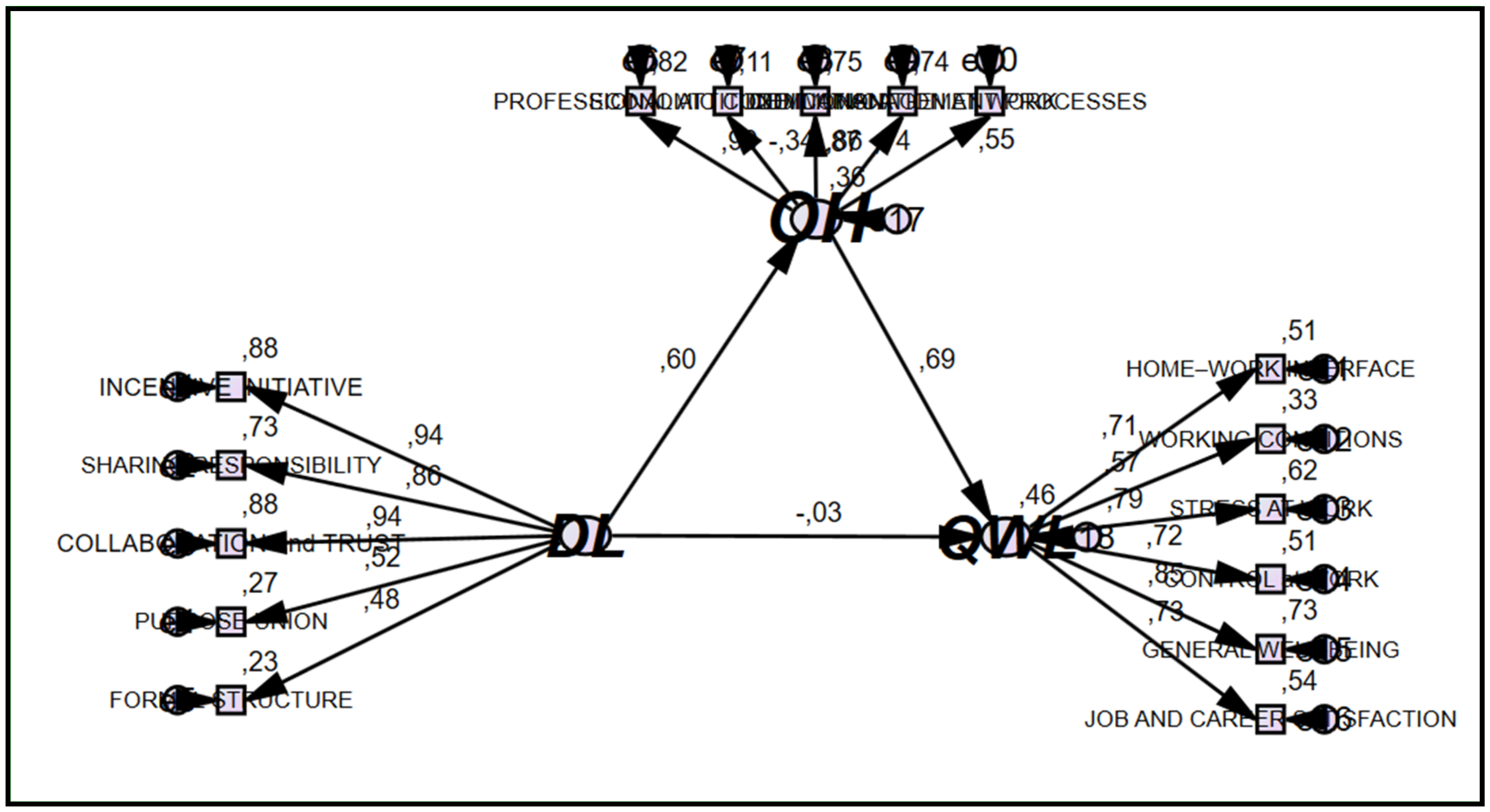

3.1.4. Testing the Structural Model

3.2. Qualitative Findings

‘Some teachers are happy with strict and commanding administrators’ (P8).

‘Sometimes a harsh approach increases the productivity of teachers’ (P11).

‘The administrator’s behavior has a direct effect on the teacher’s work life’ (P12).

‘Without doubt, it affects. If I display negative behaviors, my colleagues will be influenced negatively’ (P7).

‘There must be peace at school. The quality of work life of teachers increases in a stress-free environment. In the end, the teacher wins, the child wins, I win’ (P5).

‘The way I behave towards a teacher determines the attitude of the teacher towards me. Being polite should be made a habit’ (P11).

‘If necessary, we need to remind with gestures, mimics, or by words who the boss is’ (P9).

4. Conclusions

Suggestions for Further Studies and Practices and Limitations

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Chang, M.L. An appraisal perspective of teacher burnout: Examining the emotional work of teachers. Educ. Psychol. Rev. 2009, 2, 193–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roffey, S. Pupil Wellbeing-Teacher wellbeing: Two sides of the same coin? Educ. Child Psychol. 2012, 29, 8–17. [Google Scholar]

- Karsentfi, T.; Collin, S. Why are new teachers leaving the profession? Results of a Canada wide survey. Education 2013, 3, 141–149. [Google Scholar]

- Baleghizadeh, S.; Gordani, Y. Motivation and quality of work life among secondary school EFL teachers. Aust. J. Teach. Educ. 2012, 37, 30–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Çelik, K.; Tabancali, E. Quality of work and life of teachers’ who are working in special education institutions. Mediterr. J. Educ. Res. 2012, 11, 31–38. [Google Scholar]

- Olcum, D.; Titrek, O. The effect of school administrators’ decision-making styles on teacher job satisfaction. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2015, 197, 1936–1946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beehr, T.A. Psychological Stress in the Workplace; Routledge: London, UK, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Pascual, E.; Perez-Jover, V.; Mirambell, E.; Ivanez, G.; Terol, M.C. Job conditions, coping and wellness/health outcomes in Spanish secondary school teachers. Psychol. Health 2003, 18, 511–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Titrek, M. Employees’ organizational justice perceptions in Turkish schools. Soc. Behav. Personal. 2009, 37, 605–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cummings, T.G.; Worley, C. Organization Development and Change; Cengage Publishing: Mason, OH, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Ylitapio-Mäntylä, O.; Uusiautti, S.; Määttä, K. Critical viewpoint to early childhood education teachers’ well-being at work. Int. J. Hum. Sci. 2012, 9, 112–134. [Google Scholar]

- Corr, P.J.; DeYoung, C.G.; McNaughton, N. Motivation and personality: A neuropsychological perspective. Soc. Personal. Psychol. Compass 2013, 11, 158–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolduc, R.R. An Analysis of the Relationship between Quality of Work Life and Motivation for Correctional Services Officers in the Montreal Area. Ph.D. Thesis, McGill University, Montreal, QC, Canada, 2002, unpublished. [Google Scholar]

- Hall-Kenyon, K.M.; Bullough, R.V.; MacKay, K.L.; Marshall, E.E. Preschool teacher well-being: A review of the literature. Early Child. Educ. J. 2014, 42, 153–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lambert, L. Building Leadership Capacity in Schools; Alexandria: North Glengarry, ON, Canada, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Szabo, M. The Constructivist Leader; Teachers College Press: New York, NY, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Lambert, L. Leadership Capacity for Lasting School Improvement; Alexandria: North Glengarry, ON, Canada, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Lambert, L. Lasting leadership: A study of high leadership capacity schools. Educ. Forum 2006, 7, 134–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiménez, P.; Winkler, B.; Bregenzer, A. Developing sustainable workplaces with leadership: Feedback about organizational working conditions to support leaders in health-promoting behavior. Sustainability 2017, 9, 1944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tetrick, L.E.; Peiró, J.M. Occupational Safety and Health; Oxford Press: Oxford, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Bush, T.; Middlewood, D. Leading and Managing People in Education; Sage: London, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Lashway, L. Distributed leadership. Res. Roundup 2003, 19, 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Scribner, J.P.; Sawyer, R.K.; Watson, S.T.; Myers, V.L. Teacher teams and distributed leadership: A study of group discourse and collaboration. Educ. Adm. Q. 2007, 43, 67–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, M. Distributed Leadership and Teachers’ Self-Efficacy: The Case Studies of Three Chinese Schools in Shanghai. Master’s Thesis, University of Jyväskylä, Jyväskylä, Finland, 2011, unpublished. [Google Scholar]

- Lizotte, J.O. A Qualitative Analysis of Distributed Leadership and Teacher Perspective of Principal Leadership Effectiveness. Ph.D. Thesis, Northeastern University, Boston, MA, USA, 2013, unpublished. [Google Scholar]

- Lumby, J. Distributed leadership: The uses and abuses of power. Educ. Manag. Adm. Leadersh. J. 2013, 41, 581–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, L.M. Study of Teacher Engagement in Four Dimensions of Distributed Leadership in One School District in Georgi. Ph.D. Thesis, Georgia Southern University, Statesboro, GA, USA, 2017, unpublished. [Google Scholar]

- Tahir, L.M.; Lee, S.L.; Musah, M.B.; Jaffri, H.; Said, M.N.H.M.; Yasin, M.H.M. Challenges in distributed leadership: Evidence from the perspective pf head teachers. Int. J. Educ. Manag. 2015, 30, 848–863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hollaway, J.; Nielsen, A.; Saltmarsh, S. Prescribed distributed leadership in the era of accountability: The experiences of mentor teachers. Educ. Manag. Adm. Leadersh. 2018, 46, 538–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, A. Distributed leadership: Friend or foe. Educ. Manag. Adm. Leadersh. 2013, 41, 545–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ağirdaş, Y. Investigation of the Relationship between Distributed Leadership and Job Satisfaction on the Basis of Teachers’ Opinions in High Schools. Master’s Thesis, Okan University, Istanbul, Turkey, 2014, unpublished. [Google Scholar]

- Akyürek, M.İ. The Relationship between Primary School Principals’ Distributed Leadership Characteristics and Teachers’ Job Satisfaction Perceptions. Master’s Thesis, Gazi University, Ankara, Turkey, 2016, unpublished. [Google Scholar]

- Bozoğlu, O. Distributed Leadership Practices in Higher Education: An Action Research. Master’s Thesis, Kocaeli University, Kocaeli, Turkey, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Harris, A.; Muijs, D. Improving Schools Through Teacher Leadership; Open University Press: London, UK, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Eggen, D.D. Principals’ Perceptions of Distributed Leadership in an Elementary School Setting. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Northern Colorado, Greeley, CO, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Bush, T. Theories of Educational Leadership and Management; Sage: London, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Gronn, P. Where to next for educational leadership. Princ. Educ. Leadersh. Manag. 2010, 4, 70–86. [Google Scholar]

- Brundrett, M. What lies behind collegiality, legitimation or control? Educ. Manag. Adm. 2011, 3, 41–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edge, K. A review of the empirical generations at work research. Manag. Theor. 2008, 6, 123–145. [Google Scholar]

- Tamer, E. Determining The Factors Affecting the Quality of Work Life and The Quality of Work Life of Nurses. Master’s Thesis, Karadeniz Technical University, Trabzon, Turkey, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Cumming, T. Early childhood educators’ well-being: An updated review of the literature. Early Child. Educ. 2016, 19, 19–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korkmaz, E.; Gündüz, H.B. Leadership behaviors showing levels of managers. Int. J. Educ. Hum. Sci. 2011, 2, 123–153. [Google Scholar]

- Can, E.; Gündüz, Y.; Işik Can, C. The Role of Committee Meetings in Teachers’ Participation in Management. In Proceedings of the 2nd International Conference on Interdisciplinary in Education, Kyrenia, Cyprus, 7 March 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Teachers’ Law. TRNC Official Gazette, 3 June 1985; 2–3.

- Özkan, M.; Çakir, C. Development of a distributed leadership scale. Int. J. Eurasia Soc. Sci. 2017, 8, 1629–1660. [Google Scholar]

- Van Laar, D.; Edwards, J.A.; Easton, S. The work related quality of life scale for healthcare workers. J. Clin. Nurs. 2007, 3, 325–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akar, H.; Üstüner, M. Turkish adaptation of quality of work life scale: Validity and reliability study. J. İnönü Univ. Fac. Educ. 2017, 18, 159–176. [Google Scholar]

- Bulut, A. An Analysis of the Organizational Happiness Perceptions of Secondary School Teachers. Ph.D. Thesis, Gaziantep University, Gaziantep, Turkey, 2015, unpublished. [Google Scholar]

- Meydan, C.H.; Şeşen, H. Structural Equation Modeling: Amos Applications; Detay: Ankara, Turkey, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Miles, M.B.; Huberman, A.M. Qualitative Data Analysis: An Expanded Sourcebook; Sage: New York, NY, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Hoyle, R.H. The Structural Equation Modeling Approach: Basic Concepts and Fundamental Issues; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, L.; Bentler, P.M. Cut-off criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Struct. Equ. Model. A Multidiscip. J. 1999, 5, 1–55. [Google Scholar]

- Metin, M. Scientific Research Methods in Education: From Theory to Practice; Pegem: Ankara, Turkey, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Byrne, B.M. Structural Equation Modelling with AMOS: Basic Concepts, Applications, and Programming; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Tabachnick, B.G.; Fidell, L.S. Using Multivariate Statistics; Pearson: Boston, MA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Petersonn, R.A.; Kim, Y. On the relationship between coefficient alpha and composite reliability. J. Appl. Psychol. 2013, 98, 194–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bademci, V.A. A study on Kuder-Richardson 20, Cronbach’s Alpha, Hoyt’s analysis of variance, generalizability theory and measurement reliability. J. Ziya Gökalp Fac. Educ. 2011, 17, 173–193. [Google Scholar]

- Şimşek, Ö. Introduction to Structural Equation Modeling; Ekinoks: Ankara, Turkey, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Seçer, İ. Psychological Test Development and Adaptation Process: SPSS and LISREL Applications; Ani: Ankara, Turkey, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Çokluk, Ö.; Şekercioğlu, G.; Büyüköztürk, S. Multivariate Statistics for Social Sciences: P and LISREL Applications; Pegem: Ankara, Turkey, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, J. Assessing goodness of fit in confirmatory factor analysis. Meas. Eval. Couns. Dev. 2005, 37, 240–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preacher, K.J.; Hayes, A.F. SPSS and SAS procedures for estimating indirect effects in simple mediation models. Behav. Res. Methods Instrum. Comput. 2004, 36, 717–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ertong, C. Investigation of the Factors That Affects the Organizational Happiness of Teachers in Schools. Master’s Thesis, Gaziantep University, Gaziantep, Turkey, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Proctor, C. Effective Organizational Communication Affects Employee Attitude, Happiness, and Job Satisfaction. Master’s Thesis, Southern Utah University, Cedar City, UT, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Moçoşoğlu, B.; Kaya, A. The relationship between organizational silence and organizational happiness levels of school administrators and teachers. Harran Maarif J. 2018, 3, 52–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diddams, M.; Chang, G.C. Only human: Exploring the nature of weakness in authentic leadership. Leadersh. Q. 2012, 23, 593–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Widyastuti, U.; Maisaroh, W.; Parimita, W. Analysis of Factors in Quality of Work Life Faculty of Economics State University of Jakarta. In Proceedings of the 23rd International Business Research Conference, Melbourne, Australia, 18–20 November 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Jofreh, M.; Yasini, A.; Dehsorkhi, H.F. The relationship between EFL teachers’ quality of work life and job motivation. Educ. Leadersh. J. 2013, 5, 212–236. [Google Scholar]

- Yalçin, S.; Akan, D. Examining the relationship among the leadership styles of school administrators, teachers’ job quality and organizational commitment. Electron. J. Soc. Sci. 2016, 13, 1138–1156. [Google Scholar]

- Swathi, V.; Reddy, M. Implications of stress on quality of work life among teachers: An empirical study. IPE J. Manag. 2016, 6, 46–52. [Google Scholar]

- Spillane, J.P. Educational leadership. Educ. Eval. Policy Anal. 2003, 25, 343–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoy, W.K.; Miskel, C.G. Educational Administration; Random House: New York, NY, USA, 1974. [Google Scholar]

- Davis, M.W. Distributed Leadership and School Performance. Ph.D. Thesis, George Washington University, Washington, DC, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Louis, K.S.; Murphy, J.F. Trust, caring and organizational learning: The leader’s role. J. Educ. Adm. 2017, 55, 103–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luthans, F.; Luthans, K.W.; Luthans, B.C. Positive Psychological Capital: Beyond Human and Social Capital; Routhledge: New York, NY, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Moos, L.; Krejsler, J.; Kofod, K.K. Successful Principals: Telling or Selling? On The Importance of Context for School Leadership. Int. J. Leadersh. Educ. 2008, 11, 341–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, J.F.; Louis, K.S. Positive School Leadership: Building Capacity and Strengthening Relationships; Teachers College Record: New York, NY, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

| Age | Gender | Education Level | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Frequency | Percentage | Frequency | Percentage | Frequency | Percentage | |||

| 21–30 | 59 | 28.4 | Female | 159 | 76.4 | Associate | 4 | 1.9 |

| 31–40 | 81 | 38.9 | Male | 49 | 23.6 | Undergraduate | 169 | 81.3 |

| 41–50 | 50 | 24.0 | Graduate | 35 | 16.8 | |||

| 51 + | 18 | 8.7 | ||||||

| Total | 208 | 100.0 | Total | 208 | 100.0 | Total | 208 | 100.0 |

| Graduated School | Teaching Experience | Management Experience as School Principal | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Frequency | Percentage | Frequency | Percentage | Frequency | Percentage | |||

| ATTA | 152 | 73.1 | 1–5 years | 24 | 11.5 | 1–5 years | 2 | 16.7 |

| Private University in TRNC | 34 | 16.3 | 6–10 years | 55 | 26.4 | 6–10 years | 4 | 33.3 |

| Private University in Turkey | 22 | 10.6 | 11–15 years | 48 | 23.1 | 11–15 years | 4 | 33.3 |

| 16–20 years | 39 | 18.8 | 16 + | 2 | 16.7 | |||

| 21–25 years | 27 | 13.0 | ||||||

| 26+ | 15 | 7.2 | ||||||

| Total | 208 | 100.0 | Total | 208 | 100.0 | Total | 12 | 10.0 |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Distributed Leadership | ||||||||||||||||

| 1. Formal structure | ||||||||||||||||

| 2. Purpose union | 0.862 ** | |||||||||||||||

| 3. Collaboration and trust | 0.402 ** | 0.457 ** | ||||||||||||||

| 4. Sharing responsibility | 0.328 ** | 0.371 ** | 0.816 ** | |||||||||||||

| 5. Incentive and initiative | 0.421** | 0.471** | 0.069 | 0.816** | ||||||||||||

| Quality of work life | ||||||||||||||||

| 6. Job and career satisfaction | 0.661 ** | 0.650 ** | 0.139 * | 0.069 | 0.198 ** | |||||||||||

| 7. General well-being | 0.575 ** | 0.632 ** | 0.283 ** | 0.139 * | 0.323 ** | 0.725 ** | ||||||||||

| 8. Control at work | 0.250 ** | 0.272 ** | 0.245 ** | 0.283 ** | 0.356 ** | 0.401 ** | 0.546 ** | |||||||||

| 9. Stress at work | 0.312 ** | 0.386 ** | 0.001 | 0.245 ** | 0.367 ** | 0.520 ** | 0.617 ** | 0.733 ** | ||||||||

| 10. Working conditions | 0.176 * | 0.238 ** | 0.302 | 0.040 | 0.104 | 0.345 ** | 0.538 ** | 0.388 ** | 0.414 ** | |||||||

| 11. Home–work interface | 0.254 ** | 0.348 ** | 0.193 ** | 0.193 ** | 0.261 ** | 0.390 ** | 0.581 ** | 0.618 ** | 0.651 ** | 0.518 ** | ||||||

| Organizational happiness | ||||||||||||||||

| 12. Management processes | 0.656 ** | 0.690 ** | 0.281 ** | 0.281 ** | 0.487 ** | 0.718 ** | 0.750 ** | 0.510 ** | 0.603 ** | 0.315 ** | 0.453 ** | |||||

| 13. Professional attitude | 0.692 ** | 0.642 ** | 0.293 ** | 0.293 ** | 0.432 ** | 0.729 ** | 0.570 ** | 0.280 ** | 0.390 ** | 0.249 ** | 0.242 ** | 0.684 ** | ||||

| 14. Communication at work | 0.484 ** | 0.490 ** | 0.389 ** | 0.389 ** | 0.495 ** | 0.515 ** | 0.411 ** | 0.284 ** | 0.330 ** | 0.209 ** | 0.202 ** | 0.546 ** | 0.801 ** | |||

| 15. Dedication | 0.514 ** | 0.479 ** | 0.374 ** | 0.374 ** | 0.477 ** | 0.560 ** | 0.517 ** | 0.431 ** | 0.406 ** | 0.340 ** | 0.373 ** | 0.615 ** | 0.770 ** | 0.776 ** | ||

| 16. Economic conditions | −0.282 ** | −0.265 ** | −0.139 * | −0.139 * | −0.135 * | −0.250 ** | −0.248 ** | 0.021 | −0.115 | −0.129* | −0.081 | −0.251 ** | 0.341 ** | −0.320 ** | 2.31 | |

| Mean | 3.81 | 3.67 | 4.05 | 3.83 | 3.92 | 4.08 | 4.05 | 3.89 | 4.02 | 4.05 | 3.95 | 4.14 | 4.29 | 4.29 | 4.16 | 3.12 |

| Standard deviation | 0.74 | 0.78 | 0.69 | 0.66 | 0.66 | 0.73 | 0.65 | 0.65 | 0.61 | 0.72 | 0.70 | 0.61 | 0.62 | 0.60 | 0.65 | 0.74 |

| Observed Variable | Skewness | c.r. | Kurtosis | c.r. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| QWL- Job and career satisfaction | −1.065 | −5.687 | 1.345 | 3.590 |

| QWL- General well-being | –0.403 | –2.150 | –0.489 | –1.306 |

| QWL- Control at work | –0.298 | –1.592 | –0.149 | –0.398 |

| QWL- Stress at work | –0.368 | –1.966 | 0.093 | 0.249 |

| QWL- Working conditions | –0.453 | –2.418 | –0.521 | –1.392 |

| QWL- Home–work interface | –0.329 | –1.759 | –0.334 | –0.891 |

| OH- Management processes | –0.702 | –3.746 | 0.599 | 1.600 |

| OH- Communication at work | –0.442 | –2.359 | –0.480 | –1.282 |

| OH- Dedication | –0.315 | –1.682 | –0.865 | –2.310 |

| OH- Economic conditions | –0.206 | –1.098 | –0.768 | –2.050 |

| OH- Professional attitude | –0.591 | –3.155 | –0.550 | –1.468 |

| DL- Formal structure | –1.018 | –5.435 | 0.906 | 2.419 |

| DL- Purpose union | –0.791 | –4.224 | 0.373 | 0.995 |

| DL- Collaboration and trust | –0.682 | –3.640 | –0.347 | –0.927 |

| DL- Sharing responsibility | –0.382 | –2.037 | –0.317 | –0.846 |

| DL- Incentive and initiative | –0.562 | –2.998 | –0.285 | –0.762 |

| Multivariate | 12.478 | 2.303 |

| Distributed Leadership Scale Factors | Cronbach’s Alpha | Composite Reliability | Split-Half Reliability |

|---|---|---|---|

| DL- Formal structure | 0.872 | ||

| DL- Purpose union | 0.926 | ||

| DL- Collaboration and trust | 0.904 | ||

| DL- Sharing responsibility | 0.841 | ||

| DL- Incentive and initiative | 0.918 | ||

| DL- Total | 0.910 | 0.880 | |

| Quality of work life scale Factors | |||

| QWL- Job and career satisfaction | 0.936 | ||

| QWL- General well-being | 0.776 | ||

| QWL- Control at work | 0.725 | ||

| QWL- Stress at work | 0.809 | ||

| QWL- Working conditions | 0.918 | ||

| QWL- Home–work interface | 0.782 | ||

| QWL- Total | 0.930 | 0.853 | |

| Organizational happiness scaleFactors | |||

| OH- Management processes | 0.939 | ||

| OH- Professional attitude | 0.949 | ||

| OH- Communication at work | 0.941 | ||

| OH- Dedication | 0.880 | ||

| OH- Economic conditions | 0.855 | ||

| OH- Total | 0.940 | 0.894 | |

| The Goodness of Fit Indices | Good Fit | Acceptable Fit | OH Scale Values | QWL Scale Values | DL Scale Values |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Χ2/df | 0 ≤χ2/df ≤ 2 | 2 ≤ χ2/df ≤ 3 | 71.512/56=1.277 | 259.375/122=2.126 | 312.538/141= 2.211 |

| RMSEA | 0 ≤ RMSEA ≤ 0.05 | 0.05 ≤ RMSEA ≤ 0.10 | 0.019 | 0.031 | 0.033 |

| SRMR | 0 ≤ SRMR ≤ 0.05 | 0.05 ≤ SRMR ≤ 0.10 | 0.028 | 0.039 | 0.048 |

| NFI | 0.95 ≤ NFI ≤ 1.00 | 0.90 ≤ NFI ≤ 0.95 | 0.977 | 0.963 | 0.953 |

| NNFI | 0.97 ≤ NNFI ≤ 1.00 | 0.95 ≤ NNFI ≤ 0.97 | 0.987 | 0.978 | 0.973 |

| CFIGFI | 0.95 ≤ CFI ≤ 1.000.95 ≤ GFI ≤ 1.00 | 0.90 ≤ CFI ≤ 0.950.90 ≤ GFI ≤ 0.95 | 0.9700.979 | 0.9610.975 | 0.9490.973 |

| The Goodness of Fit Indices | Good Fit | Acceptable Fit | Model Values |

|---|---|---|---|

| Χ2/df | 0 ≤χ2/df ≤ 2 | 2 ≤ χ2/df ≤ 3 | 442.950/150 = 2.953 |

| RMSEA | 0 ≤ RMSEA ≤ 0.05 | 0.05 ≤ RMSEA ≤ 0.10 | 0.071 |

| SRMR | 0 ≤ SRMR ≤ 0.05 | 0.05 ≤ SRMR ≤ 0.10 | 0.061 |

| NFI | 0.95 ≤ NFI ≤ 1.00 | 0.90 ≤ NFI ≤ 0.95 | 0.911 |

| NNFI | 0.97 ≤ NNFI ≤ 1.00 | 0.95 ≤ NNFI ≤ 0.97 | 0.958 |

| CFIGFI | 0.95 ≤ CFI ≤ 1.00 0.95 ≤ CFI ≤ 1.00 | 0.90 ≤ CFI ≤ 0.95 0.90 ≤ GFI ≤ 0.95 | 0.924 0.913 |

| Coefficient | S.E. | T-Value | Lower | Upper | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Direct Effect | |||||

| DL→QWL | −0.030 n.s. | 0.02 | −0.348 | ||

| DL→OH | 0.598 *** | 0.03 | 18.270 | ||

| OH→QWL | 0.693 *** | 0.02 | 16.628 | ||

| Indirect effect | |||||

| DL→OH→ QWL | 0.415 ** | 0.02 | 3.246 | 0.275 | 0.549 |

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Algan, E.K.; Ummanel, A. Toward Sustainable Schools: A Mixed Methods Approach to Investigating Distributed Leadership, Organizational Happiness, and Quality of Work Life in Preschools. Sustainability 2019, 11, 5489. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11195489

Algan EK, Ummanel A. Toward Sustainable Schools: A Mixed Methods Approach to Investigating Distributed Leadership, Organizational Happiness, and Quality of Work Life in Preschools. Sustainability. 2019; 11(19):5489. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11195489

Chicago/Turabian StyleAlgan, Egemen Kemal, and Azize Ummanel. 2019. "Toward Sustainable Schools: A Mixed Methods Approach to Investigating Distributed Leadership, Organizational Happiness, and Quality of Work Life in Preschools" Sustainability 11, no. 19: 5489. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11195489

APA StyleAlgan, E. K., & Ummanel, A. (2019). Toward Sustainable Schools: A Mixed Methods Approach to Investigating Distributed Leadership, Organizational Happiness, and Quality of Work Life in Preschools. Sustainability, 11(19), 5489. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11195489