1. Introduction

Social communication today is moving into the virtual world. This also concerns public organizations which want to effectively influence their recipients and thus realize goals set for them as well as carry out actions to use the communication tools available within the network [

1,

2]. Social media which serve as channels for building relationships with residents as well as other territorial users and public service recipients are, at the same time, platforms for creating brands of public organizations or territories [

3]. According to Sevin [

4], social media have the potential to bring two important changes to the practice of place branding: local governments are able to create multimedia content with relatively smaller budgets (compared to traditional media) and social media platforms provide local governments with the tool of virtual office, an instrument that cities begin to use more and more frequently.

However, limited attention has been directed towards understanding the impact of social media communication in local government organizations [

5]. There is little recognition and understanding of the symbolic and presentational content of government communication on social media [

6]. Relatively few studies have examined how governmental agencies currently use Facebook.

An analysis of social media content allows for identifying a communication style of the city and its reception by internet users. A communication style is a basic component of the brand’s personality concept [

7]. It is defined as personal human characteristics ascribed to the brand in order to facilitate communication of its physical elements and attributes in relation to the consumer [

8].

It may be particularly interesting to link this style of communication with the specificity of an individual country, including the advancement of governance processes that are a consequence of the public management model [

9] and the level of social trust which is the result of political and historical conditions. The article focuses on Central and Eastern Europe (CEE) countries which, after World War II, became part of the Socialist Bloc. In 1989, Poland grew into an instigator of political changes which, within the subsequent two years, led to the disintegration of the prevalent political configuration of Europe (East vs. West) [

10]. A forceful pursuit of societies within those countries to adopt democratic standards along with the economic system which functioned in Western Europe became a basis for those political and economic changes [

11]. Right now, some of the CEE countries which have joined the EU can boast of having implemented a democratic structure and stable, market-based economic growth [

12,

13]. This is in part due to the substantial support they had received, first during the pre-accession period through pre-accession programs of the EU as well as later with the help obtained as part of the EU Cohesion Policy, after forming a part of the Community [

14]. Additionally, there is also the transfer of know-how and good practices in the field of public administration which, within this area, steadily brought their standards closer to those of Western Europe countries [

11].

The other group of CEE countries concerns those nations which have tried to implement subsequent phases of transformation on their own, a process that has occurred at varying rates [

15,

16]. These states still remain outside the EU, although some aspire to join the Community (Ukraine, some former Yugoslavian republics). Additionally, those being furthest East (Belarus, Moldova, Ukraine) still experience great pressure from Russia, a country which consistently strives to extend its influence over the region [

17]. As a result, the processes of systemic and economic change within these states are slower with public administration which as yet has not achieved the same level of standards as that in Western states. The impact of style of public administration on differences in communication activities carried out by local governments representing particular European nations is discussed by, among others, Bonsón et al. [

18].

The aim of the paper is to diagnose a city’s brand personality dimensions/traits used in the contents/posts of municipalities published on official Facebook accounts of cities and to identify differences within this scope occurring between city governments representing two selected Central and Eastern European countries—Poland and Ukraine, which have a varying level of development and have differing models of public management. In the process of achieving the established goal, special attention has been paid to the concept of sustainability which creates a background for the deliberations contained within this article, being the main developmental aim of contemporary cities and their brands as well as a part of the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development [

19]. In formulating the article’s aim, the authors assumed that the concept of personality, particularly detailed dimensions of city brand personality used in the process of its communication, can facilitate the implementation of sustainable development goals at a local level.

The study analyzes city brand personality projected on official Facebook accounts of cities. In literature brand personality is very rarely discussed from this perspective [

20,

21]. The authors concentrate on the issue how a city’s brand personality is communicated by this social medium especially in relation to the local community. In contextualizing this study and taking into consideration Aaker’s [

22] definition, brand personality is viewed as “the set of human characteristics associated with a particular city and how these are communicated” (on the basis of Reference [

23]). The research problem included in the aim of the paper is described by the following research questions:

are brand personality dimensions/traits identified in the Aaker [

22] model sufficient to categorize the city’s brand personality communicated by cities on their Facebook accounts and how do they refer to the sustainability concept and its implementation at a local level?

what dimensions/traits of the city’s brand personality are used in contents communicated by cities in Poland and Ukraine through their Facebook accounts?

how does the model of public management adopted within the country correspond with the city’s brand personality dimensions communicated by Polish and Ukrainian cities through their Facebook accounts?

This goal could be achieved through the use of the empirical content analysis of posts published by local governments on their official Facebook accounts. In accordance with the knowledge possessed by the authors, the thus formulated research problem has not been addressed in subject related literature published until this time. Therefore, the research performed for the needs of the present article is exploratory in character. Despite the fact that the researchers agree on the relevance of the brand personality construct in the brand image formation, brand personality theory is still in the development process [

24]. The authors’ study makes a contribution to the improvement of city brand social media communication with the use of the traits and dimensions of its personality.

The article consists of the following parts: first, the authors describe the concept of a place, including city branding and its general links with the sustainable development and the concept of city brand personality, reviewing literature on the topic. Then they describe the method of research adopted to analyze posts published by local governments representing regional capital cities of Poland and Ukraine on their official Facebook accounts. In the next part, the authors present the results of the study and conduct a discussion referring to the research carried out by the previous authors. In conclusions, they identify the theoretical and managerial contribution of the paper and point to the future directions of the subject study.

1.1. The Concept of City Branding

Cities have incessantly promoted their attractions, competing against one another for tourists, inhabitants, and entrepreneurs. They have always carried names that could be treated like a brand; still, interest in applying strategic branding to places is a relatively modern issue [

25]. This stems from the fact that within the last two decades the world has faced global economic development and rapid urbanization that intensify competition between countries, regions, and cities aimed at attracting public resources, policy support, talented workforce, and private investment [

26]. Place (including city) branding is becoming more and more popular, both as a research area and a practice used by local governments [

27]. As a research area, place branding is an evolving multi-disciplinary domain which covers a large variety of topics and disciplines, including urban planning, marketing, public policy, and sociology [

28]. As a local government practice, place branding is currently often used as a governance strategy meant to create better environmental, social, and economic conditions [

29,

30,

31]. Due to the fact that people, capital, and knowledge are increasingly less related to the location, the development of places as brands helps to foster an environment capable of attracting new forms of activity and key groups [

32]. The development of a place brand refers to the implementation of appropriate marketing strategies that allow places (also cities) to differentiate themselves from the competition through appropriate positioning of their resources/competencies of an economic, social, political, or cultural nature [

33].

Branding is also considered as a key instrument for overcoming challenges tackled by contemporary cities which block their sustainable growth, such as environmental pollution, regional disproportions, and weak economy. The appearance of such problems in a city requires balanced transformation that refers to, for example, changes in the structure of local industry or innovative infrastructural solutions [

31]. With this regard, many local governments try to introduce a place branding concept into their sustainable transformation process, treating it as an essential tool that allows for establishing a good reputation of a given city and maintaining its attractiveness among external stakeholders [

31,

34,

35,

36,

37,

38,

39].

A place brand is defined as a “network of associations within the minds of customers which is based on visual, verbal, and behavioral expression of a place embodied through goals, communication, values, and general culture of the place’s stakeholders and its overall design” [

40,

41]. The notion of a brand is connected to the concept of branding which covers intentional activities whose task is to change or improve the current image [

42] (p. 18). These activities include designing, planning, and communication of the city brand identity in order to create its desired image as well as its management [

43] (p. 11). Brands are supposed to communicate selected characteristics of a given city—functional, physical, and emotional—imbuing them with a specific meaning [

44]. Ascribing a certain symbolic meaning to a place, a brand makes it more valuable from the perspective of psychological and social needs of current and potential users (inhabitants, tourists, entrepreneurs, and so on) [

44,

45].

The element which distinguishes place branding is the necessity to include the largest number of local stakeholders into this process [

46,

47]. Since this concept is an element of public management all activities connected to it require the support of public opinion both for political as well as social reasons [

48]. It must also be remembered that place brands have many more functions than the brands of commercial products. When it comes to the notion of a territorial brand, it deals with a place where people live, work, and study, a place where relationships are formed and which should ensure that the communities inhabiting it can enjoy numerous basic needs [

49].

Place branding is a complex process—it must account for many factors and associations in the process of shaping a brand of a given territory, including for example: local attractions, natural reserves, local products, institutions, and infrastructure, as well as features of inhabitants [

50]. Despite the fact that the process of place branding engages many stakeholders [

44], the role of coordinating these measures is assigned to local governments and their institutions. In making a decision to pursue the strategic approach to shaping the desired image of a city, local governments search for elements of identity which will allow them to build an attractive image both externally as well as internally (understood as the way in which it is perceived by its inhabitants) [

51]. Among these components there increasingly emerge issues concerning a city’s sustainable growth [

39], including its positioning as an eco-oriented city, green city, innovative, or smart city [

31,

52], livable or just sustainable city [

53]. In the literature, there are different ways of defining the term “sustainable city”, but these different approaches contain several common features, such as: the systematic or ecological consideration of city functioning, care for the local quality of life, and residents’ satisfaction with city life, activities aimed at social inclusion or enabling social participation in city management [

19,

53]. The concept of a city brand is undoubtedly connected to the concept of the sustainable city as well as associated with various aspects of basic necessities and attractiveness that are crucial to city users in decision-making [

53].

Place branding is an area where political decisions play an important role and, as a result, is connected to the local administrative organization and procedures for the execution of a local policy [

40]. Wæraas et al. [

54] even propose to divide branding activities undertaken by territorial units into three types of strategies: (1) place branding (a municipality is treated as a geographic entity), (2) organizational branding (a municipality as an administrative entity), and (3) democracy branding (a municipality as a political institution).

In conclusion, it can be stated that contemporary place branding goes beyond the traditional place promotion and focuses on creating a strong brand image capable of binding together all these functional and new symbolic meanings; towards a more effective approach [

55]. Place branding as a very broad governance strategy also goes beyond managing image and perceptions [

56]. Within this concept it can also be a strategy for city management which effectively attains sustainable development goals at the local level [

37]. Despite the fact that there it is an inevitable relationship between a city brand and city sustainability, an observable knowledge and conceptual gap exists because of a shortage of research concerning this issue [

36].

Since place branding is a relatively new area of academic exploration, researchers that undertake this issue reach for theory and practice that belong to other disciplines, for example, psychology [

57] (p. 26). One such idea that is beginning to be implemented in marketing and branding is brand personality [

58]. The latest source literature even claims that building strong and consistent brand personality is crucial to the position of cities in the global context and a key element to influence potential visitors’ behavior [

24].

1.2. The Concept of Brand Personality and Its Application in the Context of City Branding

The concept of brand personality results from the transfer of this idea from psychology to marketing. According to it, brands, like individuals, can develop personalities that are actually similar in their characteristics [

22]. In recent years, the brand personality concept has been very popular in the field of marketing research. Imbuing brands with traits typical to people is described as brand anthropomorphism. According to this concept, brands are perceived by consumers as human beings [

59], characterized by emotions, thoughts, and conscious conduct [

60]. The growing popularity of the brand’s personality concept is connected to the increase of non-functional properties of the brand in a consumer decision-making process in the face of unifying the functional properties of different brands within a given product category [

61]. The role of brand personality as a construct that affects consumers’ decision making is also highlighted within place branding in literature [

58].

The concept of brand personality is strongly related to the concept of brand identity and image. Some authors conceptualize the concepts of identity and brand image as multidimensional constructs in which brand personality is an important component [

8]. Other authors [

62] indicate that brand identity can be shaped through forming its personality. Brand image is imbedded in “hard” and “soft” associations caused by product attributes, where the former refers to material (functional or physical) properties, and the latter to intangible features. Brand personality is based on “soft” (intangible) associations and covers an emotional side of brand image [

60,

63,

64]. The previous research pointed out that, among all the different associations forming a brand image, brand personality is a key component contributing to the different stakeholders’ and partners’ brand alignment, creating a common, consistent proposition in consumers’ minds [

24].

Brand personality understood as “a set of personality attributes/features connected with a brand” [

22], should be considered from two perspectives [

8]: firstly—how the brand presents itself in the environment (brand identity, that is the sender’s side), and secondly—what is the current social perception (brand’s image—recipient’s side). The association of human characteristics with brands can radically increase the possibility of differentiating a brand image against competing brands and thus creating a unique selling proposition [

8]. Imbuing a brand with a strong personality, brand strategists can differentiate it from others offering similar products [

20]. In this way, they can give it a sustainable competitive advantage. An original brand personality affects the growth of its value, encourages customers to choose a given brand, and creates strong bonds with them, as well as invoking their emotional associations, which leads to enhanced trust and stronger loyalty [

65]. Moreover, the concept of brand personality is also applied with regard to not only traditional goods and services, but also to other categories of “products”, such as luxury goods [

66], corporations [

67,

68], non-profit organizations [

69], and political parties [

70]. In recent years the concept of brand personification has gained popularity in regards to research concerning locations, in particular in city, region and country marketing [

71].

Due to the growing popularity of the place brand concept, which has really grown within the last two decades (both among academics and practitioners), some authors have already attempted to adapt the brand personality concept into the context of branding territories: tourism destinations [

58], cities [

33,

72,

73,

74], regions [

75], and countries [

76].

The most popular concept for gauging the personality of a brand is the Aaker model [

22], who, for this purpose, created a research tool, the so-called brand personality measurement scale (

The Brand Personality Scale). Aaker identified 42 personality characteristics, grouped into 15 traits and then into five dimensions:

Sincerity,

Excitement,

Competence,

Sophistication, and

Ruggedness. The dimensions and the traits are presented in the

Table 1.

Despite the fact that some researchers (for example Reference [

77] cited in References [

59,

71]) suggest that Aaker [

22] measure may not adequately represent personality of the place, the model is still widely used in scientific research as a starting point of conducting studies [

64,

73,

74]. According to Tugulea [

60], some researchers have proposed a different approach to the City Brand Personality Scale, such as including refined traits from previous tourism studies [

78] or reconfiguring the scale completely [

33]. Research conducted by Hosany et al. [

58] identified three dimensions of a location’s brand personality:

Excitement,

Sincerity, and

Festiveness.

Sincerity and

Excitement are two dimensions of city brand personality found in the research of Papadimitriou et al. [

78]. Research carried out by Usakli and Baloglu [

73] in relation to Las Vegas identified five dimensions of brand personality, such as:

Animation,

Sophistication,

Sincerity,

Competence, and

Modernity. To meet the aims of their study, Kaplan et al. [

33] defined city brand personality as “a set of human characteristics associated with a city brand”. Their research identified six brand personality dimensions for places:

Excitement,

Malignancy,

Peacefulness,

Competence,

Conservatism, and

Ruggedness. Glinska and Kilon’s [

64] study identified three specific, considered to be desirable, dimensions of the City Brand Personality Scale adapted for medium and small cities of Poland:

Conservatism,

Peace, and

Neatness.

According to Kaplan et al. [

33] a city’s brand personality dimensions differ from the dimensions proposed in the Aaker model [

22], because a city is a specific, multidimensional product, and associations with it are the result of a combination of its utilitarian, symbolic, and empirical attributes that are the product of heritage, environmental and spatial aspects, characteristics of residents, and city activities. The cultural context in which cities operate is also of great importance here. As previous research shows, some brand personality traits are common across cultures and others are culturally specific [

79].

Researchers who took up the topic of place brand personality assume one of two possible approaches to the analysis of this construct: perceived brand personality and projected brand personality [

20,

80]. The first concerns identifying the perception of the brand’s personality of a given place by a specific target group (for example, tourists or residents). The second approach (definitely less frequent) concerns research related to the definition of the projected brand personality, which means the identification of its communication strategies carried out by local government authorities or other institutions using various methods of promotion [

80]. While there is a vast volume of research exploring the perception of consumers about different brands’ personality, there is much less research focused on the assessment of the projected one [

20]. Regarding the second approach, the research of Pitt et al. [

23] provides an excellent example. These authors were the first to propose a systematic methodological approach to projected place brand personality assessment. Implementing special software, they used the analysis of the vocabulary used on the official websites of African countries addressed to tourists in order to identify personality traits of their brands. According to the authors’ assumptions, the material they analyzed included the message communicated on countries’ official tourism websites. They did not measure a brand’s personality by what others think it to be, but rather, what the country says about itself [

23]. Since then this approach to the projected brand personality assessment, which is mainly identified by the analysis of the content of web sources [

24] has been used in several studies. The research approach presented in the paper is part of this trend.

It is, therefore, necessary to further adapt it to the context of social media communication which is becoming a leading instrument for cities’ image creation. The authors assume that this style of city brand communication is a derivative of the model of public management adopted in particular countries. Following research performed by Osborn [

81], it can be assumed that in individual countries there is a dominance of one of three models of public management:

Public Administration—PA (a bureaucratic model based on the idea of organizational rationality, it was to ensure maximum standardization and simplification of activities and the hierarchical exercise of power)

, New Public Management—NPM (a model based on usage of the instruments from the private sector to increase the efficiency of the organization), and

New Public Governance—

NPG (model which favors strengthening cooperation between administration and various stakeholders for the benefit of the final service recipient, based on network management). Each one may have a specific impact on the way a public organization communicates with its environment as well as potential impact on the city’s brand.

The problem of municipal branding has not until now been more broadly discussed in the context of public administration models that define the manner in which that public administration realizes its given tasks. Within literature concerning territorial branding, the issue of public administration is addressed by Dutch and German authors who in branding see tools for the support of local governance processes [

44,

82]. The

NPG model mentioned above is based on the sharing or the engagement of inhabitants and institutional stakeholders in executing authority and city management [

83]. A different model of public management based on market rivalry (

NPM) appears in literature in the context of developing indicators of effectiveness for city brand strategy [

84]. However, the issue of a city’s brand personality traits/dimensions, connected to the public management model assumed in city administration discussed within this article has not, so far, been the subject of scientific study.

2. Materials and Methods

The research method used to obtain the empirical material for the needs of this article was content analysis, an approach to analysis of documents and texts (which may be printed or visual) that seek to quantify content in terms of predetermined categories in a systematic and replicable manner [

85] (p. 302). The choice of the method results from the fact that content analysis is an especially useful method in advertising [

86]. Research results gathered through the content analysis of posts were analyzed with consideration for the exploratory and interpretative character of the research material [

87].

The subject of analysis consisted of official Facebook accounts of 34 cities from Poland and Ukraine. Content analysis of Facebook accounts of local governments is represented in literature [

88]. Justification for the selection of research sample cities is presented below.

A qualitative study based on the researchers’ assessment of Facebook posts was the chosen research method. 800 posts from Polish cities and 900 posts from Ukrainian cities were evaluated. They were published during the same period of time, starting on the date of 15th November 2018. However, the ending date varied for individual cities depending on the frequency of published posts. The observation was carried out until the official Facebook account of a given city reached 50 posts. For Polish cities who were active in this respect the research period was 27 and 28 days for Gdańsk and Katowice while for relatively fewer active cities (such as Łódź or Kraków) it was as long as 50 days. When it comes to Ukrainian cities, a much larger disproportion in the frequency of published posts has been observed. As a consequence, the 50-post limit was reached in such cities as Dnipro or Uzhorod in as little as 12 days but lasted much longer (78 days) for Lutsk. The full content analysis (photos, text, video, audio) of Facebook posts was done using the inter-coder reliability approach. The two coders were native speakers (Polish and Ukrainian languages) who cooperated with each other on a day-to-day basis (discussing interpretations of messages contained within the posts).

The content analysis consisted of the following steps: (i) appearance of a new post and familiarization of coders with its content including photos, text, video, or audio, (ii) description of the post (as a whole) using one, two, or three personality traits from the 15 characteristics contained within the Aaker scale (level 1 in

Table 1) or additional characteristics proposed by the coders, (iii) in case of doubts regarding post assessment, coders initiated discussions to determine the most acceptable interpretation, and (iv) in situations where a new trait was proposed by one of the coders (not included in the Aaker scale), that fact was communicated to the other coder.

The aims of the article were achieved through directed content analysis [

89] (p. 1281), in which, during the coding process, researchers make use of both codes formulated on the basis of the existing theory as well as the ones which they develop themselves relying on obtained results. The goal of the directed approach to analysis was the desire to verify whether the personality brand model proposed by Aaker [

22] will permit the description of a city brand personality projected through posts published on Facebook or if this theoretical proposal will need to be expanded. Additional categories which have been created in the process of the completed content analysis allowed the enhancement and improvement of Aaker’s proposition, as well as adapting it to the specific character of a city brand. The utilization of directed content analysis provided the coders with the ability to formulate city brand personality attributes resulting from their own reflections and observations.

The Aaker model was chosen as the starting point for the content analysis, since as it was mentioned earlier, this model is most often used in studies on the personality of the city brand [

73,

74], the exception in are the works [

21,

33].

The brand personality scale proposed by Aaker [

22] concerned product brands, which creates questions regarding whether it can be adapted to place personalities as well as how individual traits should be interpreted in respect to cities. In addition, it is worth emphasizing that other authors argued that the same trait item can have different meanings when associated with different objects [

59,

71]. The complexity of cities, along with the communities that inhabit them, local governments, public, social, and private organizations which function there or issues concerning local infrastructure, environmental conditions, or historical and cultural identity also needed to be considered. The manner in which individual brand personality dimensions of a city, with its specific, complex character, were interpreted has been presented in

Table 2.

Within this article, the issue of city brand personality is addressed in the context of sustainability, which induces the authors to attempt to determine the role of this concept in the development of modern territories and connect it with the dimensions listed in

Table 2. A document which defines the directions of activities meant to ensure the sustainable development of the world is the Agenda 2030 for Sustainable Development [

19]. Its seventeen Sustainable Development Goals (SDG) encompass an entire spectrum of areas concerning the broadly understood concept of sustainable development, including: fighting poverty and hunger, striving to improve healthy living conditions, promotion of stable, sustainable, and inclusive economic growth, implementation of models for sustainable consumption and production, etc. In the context of our study, SDG 11 (

Make cities and human settlements inclusive, safe, resilient, and sustainable) deserves special consideration. Cities are closest to their inhabitants and, as a consequence, the scope to which the aims of sustainable development can be implemented, depends on them, on their understanding of existing problems, and their engagement toward sustainable development in a manner postulated by Agenda 2030 [

19].

Justification of the Selection of Countries/Cities

To show a correlation between the dominant public management model and the dimensions of city brand personality, the authors decided to consider in their analysis countries whose administrations vary considerably in respect to their development but, at the same time, lack fundamental cultural or civilizational differences. The region of Central and Eastern Europe, divided into countries that have joined the EU as well as those who remain outside of this community, is a good example. It was assumed that the research will concern cities from two countries: Poland, located in Central Europe, and Ukraine, which is part of Eastern Europe. These two nations share a border which is also the external border of the EU.

Table 3 presents the general characteristics of both countries and shows that Ukraine is the larger of the two, especially in terms of area, and is similar to Poland in respect to population and political system but with an economy which is at a much lower level. Poland, which became a part of the EU in 2004, was (during the period covered by the study) a much faster economically developing country within the CEE region.

In order to better illuminate the situation of countries included in the study in respect to their level of democratic processes, the rule of law or administration the authors utilized the results of the so-called Worldwide Governance Indicators (2017), developed by the World Bank, an organization which systematically monitors democracy and the rule of law in numerous countries of the world allowing comparisons between nations and the assessment of the distance between them in this respect.

Table 4 demonstrates indicators for Poland and Ukraine. All indicators show that Ukraine is far behind in all areas. Poland has higher values, but the distance separating it from the well-developed states of Western Europe and the world is still quite considerable.

It can be assumed that in Polish local administration the NPM approach is introduced with the elements of the NPG model. It is the result of a long-term support for reforms in the area of public administration from the European Social Fund. In contrast, Ukraine, despite previous attempts to implement adequate reforms, has failed to radically change the status quo [

93,

94]. Thus, it remains a country with a traditional administrative system (both at state and local levels) that is based on hierarchy, dependent on its political system and characterized by a low level of trust [

94,

95,

96],

For their research the authors selected cities using the same criteria for both countries:

cities which carried out considerable activity on Facebook: having established an official account and publishing at least one post a day,

large urban centers where it was assumed that communications are not carried out by one person but are a part of the work and cooperation of various individuals and entities,

cities exhibiting similar administrative function and importance in both considered countries.

Guided by similarities in the structure of territorial division of both countries being studied, it was accepted that the activity of regional capitals will become the subject of analysis. As a result, the research considered all Polish voivodship capitals (16) and 18 Ukrainian cities (during the period covered by the study there were a total of 24 oblast capitals in Ukraine). Six cities were excluded from the study because at the time they did not have an official Facebook account. Three of them (Simferopol, Lugansk, and Donetsk) were occupied by Russian forces while the other three oblast capitals sharing a border with that country were not at this time active on Facebook. It must be said that in contrast to earlier studies this work did not focus on cities which are considered tourist centers (most research concerns the domain of tourism) [

58], but rather on urban centers which play the role of administrative regional capitals, local economic and educational centers, and whose connection to tourism relates more to business or is connected to weekend city breaks. This means that their communication through social media is mainly directed at its permanent residents.

The following procedure has been used to identify statistically significant differences on the level of personality dimensions of a city brand between Poland and Ukraine. For every selected city, the number of observations for each of the 18 personality traits of a city brand was added up. The value of every variable for a given city informs of how much specified content indicating a given personality trait had been found within 50 posts. Next, unitarization of all 18 partial variables, using formula (1) accounting for the maximum and minimum of all 34 cities being considered, was performed [

97].

The range of variation for each of the 18 partial variables was [0;1].

In the next step, the average value of variables for each dimension (on the basis of data resulting from the unitarization) was identified. In this manner, 6 variables measuring the level/intensity of city brand personality were established: Sincerity, Excitement, Competence, Sophistication, Ruggedness, and Prosocial Attitude. The range of variation of every variable fit within [0;1].

A t-test for Equality of Means was utilized to compare the average of individual dimensions within both countries. It was conducted using Levene’s test results (the version of the t-test was selected depending on whether equal variances could or could not be assumed). It was assumed that differences between countries are statistically significant if p < 0.05. Calculations were performed in MS EXCEL and IBM SPSS Statistics (PS IMAGO 4.0).

3. Results and Discussion

As shown in the description of this paper’s research method, the coders described posts with the use of a list of 15 personality traits that make up the 5 dimensions of personality from the scale developed by Aaker [

22] (

Table 1). However, there were posts for which they made a decision to suggest new traits because the use of only the attributes contained within the scale did not allow for the formulation of reliable descriptions. As a result of the entire coding process, a total of nine new, more detailed characteristics were identified that were then grouped into three new traits of city personality: patriotic, cooperative, and bureaucratic (

Table 5).

The identification of brand personality traits and dimensions that go beyond the Aaker model had already appeared in the results of previous research [

33,

64,

73,

74]. It is due to the fact that the construct of City Brand Personality depends on more diverse factors than the brand personality of conventional products [

60].

The

Patriotic feature, a suggested city brand personality trait, consists of five specific characteristics which, in the opinion of the authors, correlate with one another and are communicated in a parallel manner. These include: love for one’s country, national pride, and proclaiming one’s religiousness, as well as, at the same time, communicating the feeling of having been wronged by other nationalities in recent past or historically. It should be noted that a similar and new personality trait, dubbed conservatism, has also been identified in the research carried out in Turkey and Poland [

33,

63]. However, in that case, there was a lot of stress placed on values resulting from the high level of religiousness of the Turkish and Polish society and the characteristics of local communities being a consequence of their faith.

Emotions which in this study fall into the patriotic category are mainly visible in the posts of Ukrainian cities. This trait has been used to describe 8.5% of posts from cities of that country, while in similar posts from Poland it was only 2%. It is of note that since 2014 there has existed an open military conflict between Ukraine and Russia, which has a direct impact on the hostile social attitudes of Ukrainians toward the Russian aggressor. Those and other emotions connected with the feelings of having been historically wronged furthermore add to national pride. It should also be mentioned that the analysis of posts and their patriotic trait (in Ukraine) mainly relates to the national level and less to the city level. Although important national or religious holidays are celebrated by governments of cities and their inhabitants, these feelings are connected with national pride rather than with being proud of one’s city or of belonging to a local community. When it comes to posts from Polish cities, there are fewer references to the past and historical grievances although Poles have also suffered throughout their history [

10]. Posts from Facebook accounts of Polish cities have relatively few references to the past, based on reports from annual celebrations commemorating historical events being less frequent, and—some—having been identified as having characteristics falling into the

Excitement category and being of positive resonance.

Another category which, according to the authors, should be added to the Aaker scale are those characteristics which can be considered as cooperative. This trait has been used to describe 4.7% of Polish and 7% of Ukrainian posts under study. It considers all manifestations of attitudes concerning cooperation: working together in governing the city, or the relationship between the local administration and the inhabitants or their representatives (including them in decision making regarding public matters), relationships of local governments with partners from outside the city, with higher-level authorities or other external organizations. This category also included the activity of local community organizations based on the cooperation of people and institutions as well as the collaborative, responsible approach to financing pro-social initiatives. In Ukraine, these types of schemes are new and are, therefore, strongly promoted through all forms of communication with the local community. The cooperative trait gains special significance in the context of the 2030 Agenda [

19], especially as it concerns SDG 17 (

Strengthen the means of implementation and revitalize the Global Partnership for Sustainable Development) which refers to the ability to implement directions of development defined within this document. This goal, interpreted at the local level, relates to establishing cooperation with local stakeholders meant to engage them in shared activity toward sustainable development. The last of the suggested trait—bureaucratic—is mainly connected with the style of information transfer and seems to be very strongly connected with the standards of local public administration. It has been used to describe 5.2% of posts from Ukrainian cities and 0.1% of all analyzed posts from Polish cities. In comparison to the Polish cities, posts published by Ukrainian cities are longer, are presented less frequently, their content is less attractive, and they have a less emotional character. The inclusion in posts of formal documents and pictures of working meetings without providing emotional background is indicative of the administrative backwardness of regional Ukraine. Although Ukraine is implementing decentralization reforms as part of the process meant to adapt public administration to EU standards [

98], these are slow and have not yet had much of an impact on increasing the quality of service for residents [

96,

99].

The emotional presentation of patriotic posts inclines the inclusion of this characteristics into the Excitement dimension. The presented posts, especially those published in Ukraine, often contained the national flag, folk costumes, and images of the military, while their descriptions were energetic and emotional. It was decided that the other two, new personality traits (cooperative, bureaucratic) which concern the manner in which administration functions will become a part of the newly established dimension named Prosocial Attitude.

Within a broader context, it can be accepted that the

Prosocial Attitude corresponds with the dimension of

Sincerity which shows a city’s sensitivity to social problems—problems of individual people and their environment (

Table 2), while the dimension of

Prosocial Attitude expresses how cities operationalize activities within this scope. This style corresponds directly to the given country’s accepted model of public management which was described in the introduction to this paper (

PA versus

NPM/NPG). Both mentioned dimensions—

Sincerity and

Prosocial Attitude, most broadly concern current aims for sustainable development, defined in the 2030 Agenda [

19] (SDG 11 and SDG 17 respectively), and ways for their development at a local level. They show a city’s (local administration and its residents) sensitivity to social problems and the quality of the environment (

Sincerity), as well as show the style which is used by the city to initiate preventative and corrective actions (

Prosocial Attitude). The broad list of aims related to the sustainable development approach opens ground for search for other connections within the structure of city brand personality attributes. Other characteristics making up the measuring scale of city brand personality can be tied to sustainable development and interpreted as showing a responsible approach toward the natural environment (reliable) or, for example, appreciation for the quality of the natural environment (charming). However, within the context of sustainable development, the authors of the paper decided to draw attention only to those dimensions of city brand personality which, in their opinion, through their traits are most closely related to people and their environment.

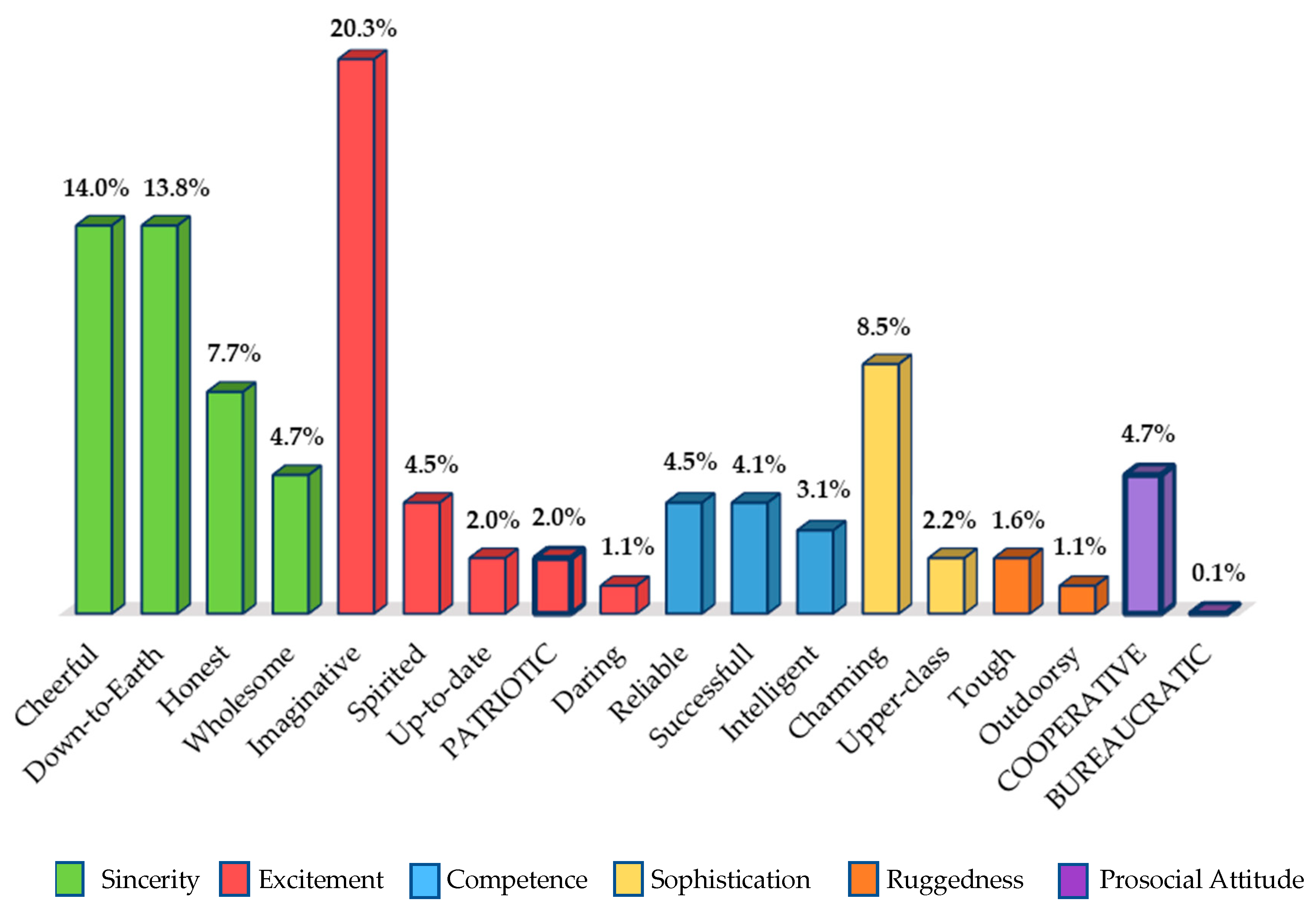

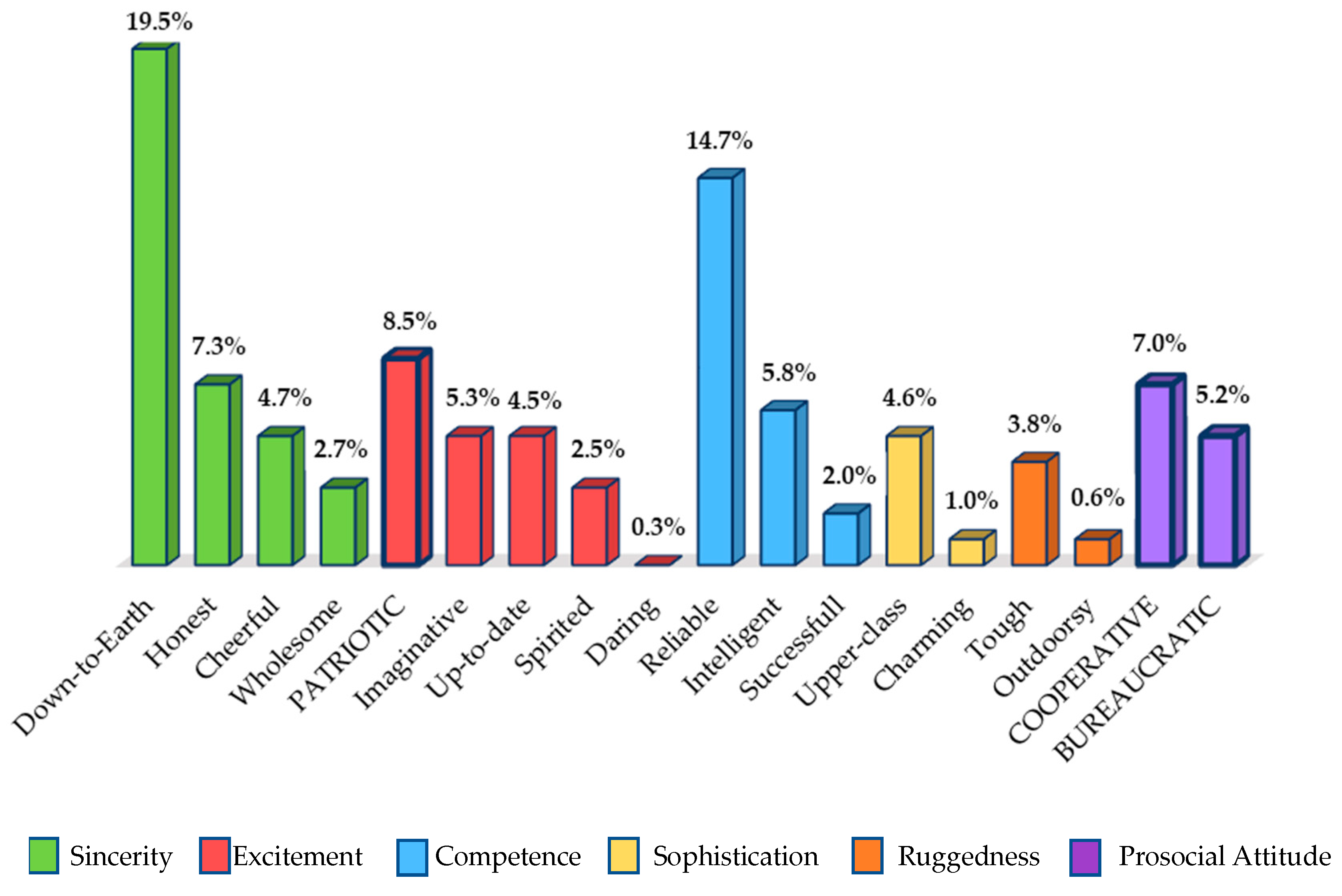

Taking into account the newly identified personality traits, quantitative summaries presenting percentages of the usage frequency of individual brand personality dimensions as well as their individual traits in the communication of cities realized through their official Facebook accounts, were prepared (

Figure 1 for Poland and

Figure 2 for Ukraine). All together these included 18 characteristics grouped into 6 dimensions of personality, from the left:

Sincerity (highlighted in green),

Excitement (red),

Competence (blue),

Sophistication (yellow),

Ruggedness (brown),

Prosocial Attitude (violet). The new characteristics—patriotic, was included into the

Excitement dimension. The cooperative and bureaucratic traits formed the

Prosocial Attitude dimension.

On their official Facebook accounts, the analyzed Polish cities mainly communicate through the

Sincerity and

Excitement dimensions. Ukrainian cities, on the other hand, generally use

Sincerity and

Competence. During interpretation, however, it should be stressed that both above mentioned dimensions contain a doubled number of characteristics than the other ones, such as, for example,

Sophistication or

Ruggedness, which can impact their importance in the summary. Similar results were obtained by Kim and Lehto [

20], who analyzed the content of a Korean tourism website. Among the most frequent dimensions of place personality there appeared

Sincerity and

Excitement, and less often

Competence,

Sophistication, or

Ruggedness, which appeared sporadically.

As presented below, the authors take a closer look at the structure of individual personality traits, paying attention to the differences between cities representing the two countries: Poland and Ukraine. Although the elements of the Sincerity dimension have similar total value—40.2% and 34.2%, respectively, their structure is different. In relation to Ukrainian cities, the down-to-earth characteristics dominates the Sincerity dimension, while—when it comes to Polish cities—the values of individual traits are more similar to each other. The situation is reversed with regard to the Excitement dimension, where Polish posts are dominated by the imaginative characteristics (20.3% of all posts of Polish cities) connected with the practice of publishing attractive pictures showing beautiful places within a given city, often described through the use of this attribute. With respect to Ukrainian cities the dominant characteristics within the Excitement dimension is the patriotic attribute (8%), while the imaginative characteristics mentioned above is used to describe only 5.3% of posts.

Competence is the next dimension. In relation to Polish cities, the values of traits making up this dimension are at a similar level to each other: reliable (4.5%), successful (4.1%), and intelligent (3.1%). Posts of Ukrainian cities are much more varied with the dominant characteristics being: reliable (14.7%). On the Aaker scale, the Sophistication dimension is represented by only two traits which can be significant in the overall comparison of all five dimensions. The dominant attribute characterizing Polish posts is charming. It was used to describe as many as 8.5% of posts of Polish but only 1% of Ukrainian cities. In respect to this group of posts, the Sophistication dimension is represented mainly through the upper-class trait. The next dimension is the one of Ruggedness. The posts of Polish cities were only sporadically marked with such features as outdoorsy or tough. On the other hand, Ukrainian cities were more likely to publish posts marked with these features. It is worth mentioning that the dominant feature of Ukrainian posts in the category of Ruggedness turned out to be tough (3.8%) which marked only 1.6% posts of Polish cities. The newly defined dimension (Prosocial Attitude) is represented in the case of Polish cities with cooperative (4.7%) and bureaucratic (0.1%) traits. In case of Ukraine, these numbers are much higher—7.0% and 5.2%, respectively.

Table 6 presents total values for personality traits describing posts published on official Facebook accounts of cities from Poland and Ukraine analyzed through the study. These values have been classified into six dimensions of personality. It demonstrates dimensions showing significant differences between cities from Poland and Ukraine. In comparing brand personalities of cities from Poland and Ukraine, a synthetic assessment of each one was completed for individual cities (n1 = 16 for Poland and n2 = 18 for Ukraine). The higher the variable’s level (closer to 1), the higher the level (intensity) of a given city brand personality trait. The comparison of average values for cities (the average from the normalized number of posts within a given dimension of the particular city from a given country) allow for juxtaposing brand personalities of cities from Poland and Ukraine.

The data presented in

Table 6 confirms clear differences between the average score of the six city brand personality dimensions in the two countries under investigation. This especially concerns

Sincerity,

Excitement, and

Sophistication (higher value of mean and median for Poland) and

Prosocial Attitude (higher value of mean and median for Ukraine). This data shows that in Poland

Sincerity and

Excitement were recorded at the highest level (mean at the level 0.46–0.43, for half of cities the level of variables is not lower than 0.48 for

Sincerity and 0.46 for

Excitement), while in Ukraine the average and the mean were nearly half of those values. The value of

Sophistication in Poland is also almost a double of that for Ukraine and—in respect to

Prosocial Attitude—this is reversed, meaning the values for Ukraine are almost double of those for Poland.

Additionally, from the perspective of comparing the two samples, both skewness as well as kurtosis are relatively low and the results of the Shapiro–Wilk normality test are statistically insignificant (the only exception is

Sophistication for Ukraine—

p = 0.300 but the skewness and kurtosis are quite low—close to 1). This fosters the use of the

t-test for Equality of Means (Independent Samples

t-test) for the comparison of city brand personality dimensions in the two countries being investigated (despite a small number of cities in Poland and Ukraine). The results of this test indicate that significant differences between countries occur in indicators referring to such dimensions as:

Sincerity,

Excitement,

Sophistication, and

Prosocial Attitude with values in the last column being at a level lower than 0.05 (

Table 6). In the other two dimensions (

Competence,

Ruggedness) it can be concluded that the differences between the two countries are not statistically significant.

A comparison of the above dimensions of city brand personality conducted on the basis of an analysis of communication addressed at cities’ inhabitants through Facebook allows for identifying significant differences between the two countries. In respect to the dimension of Sincerity, Polish cities have certainly shown greater sensitivity to people/inhabitants and the environment. In their posts, they communicated the beauty of the world which surrounds them and promoted care for the environment. The attributes of city personality making up this dimension are additionally worth a closer study. These include being down-to-earth, or showing concern for other people and being devoted to their problems, promotion of a healthy lifestyle and doing sport (being fit and healthy), as well as spiritual serenity (being cheerful) and observing social norms and standards (being honest). In relation to the Sophistication dimension, which is mainly based on values of characteristics of upper-class and charm, its relatively small impact on personality is not surprising when it comes to Ukraine. This is especially noticeable in the context of structural economic and social problems which slow the rate of changes and transformation, particularly in respect to the physical and infrastructural sense. An even greater difference has been observed when it comes to the dimension of Excitement. Despite the fact that a new trait was added into its ranks, patriotic—which is strongly represented in the communication of Ukrainian cities, in comparison with those of the Polish cities the Ukrainians base their posts on emotions much less frequently. A significant variance has also been noted with respect to Sincerity, where it can be seen that Ukrainian cities listen to the voice of their inhabitants to a much smaller degree, which could in turn be a consequence of a lower level of local democracy.

If the division of branding activity initiated by municipalities into three types of strategies [

54] is accepted, then the posts of cities from Poland and Ukraine considered in the study should be qualified into separate strategies. The contents of posts published by Polish cities provide a basis for claiming that, in their majority, they fall into the first category mentioned above, that of “place branding”. This is seen in the subject matter addressed by the posts which can be of interest not only to city inhabitants but also other target groups, such as: tourists, visitors, investors, and new residents. The Polish posts show that reliance on and collaboration with key local stakeholders is typical in their content. The analysis of the Ukrainian posts, on the other hand, inclines toward classifying most of these activities into the strategy defined as “democracy branding”, since it is possible to get the impression that these posts are addressed solely to the city’s residents, the potential voters. The Ukrainian strategy of democracy branding plays on emotions, aiming to make local voters feel that they can trust their democracy. This strategy is to be based on transparency and citizen participation. Therefore, Ukrainian posts are full of political and legal documents, meetings or broadcasts presenting activities initiated by the municipal authorities. These cities conduct their communication through Facebook in a bureaucratic manner, representing the standards of local public administration which has not undergone systemic changes. It is characterized by a formal style based on simple transfer of information about conducted meetings or events without adding emotional content or on including unprocessed text documents, the ones that have not been adapted to the contemporary recipient. There have even been incidences of publishing legal documents—agreements or contracts, which does not fit into the informal character of social media. The bureaucratic manner of Ukrainian posts is also reflected in their relative lengthiness. The communication content in the posts of Polish cities is shorter in relation to text, better visualized—photos are of better quality, and more often conveying positive emotions. There is also an increasing number of pictures presenting attractive portions of the city and places which have undergone necessary repairs or restructuring.

The classification proposed by Wæraas et al. [

54] allows for a more profound interpretation of the analysis of posts published by municipalities covered in the study. For example, the

Prosocial Attitude dimension, which was relatively often used to describe posts published by Ukrainian cities, only seemingly suggests that these cities are initiating pro-social activities. In reality, from the perspective of the abovementioned democracy branding strategy, these mainly include activities which are not directed at promoting the well-being of residents or the environment but are meant to make the local authorities and their work look good in the eyes of potential voters.

4. Conclusions

The presented empirical material supplements the Aaker scale [

19] with such traits as: patriotic, bureaucratic, and cooperative. It should be stressed that, although for Polish cities the Aaker scale turned out to be 93.2% concurrent, in respect to Ukrainian cities, that value reached only 79.3%. In this case, 20.7% of determinations were assigned to the newly proposed attributes. The dimension coined

Prosocial Attitude was proposed to integrate two new personality traits: bureaucratic and cooperative, and relates to the way in which cities approach the problems of their inhabitants and their surrounding environment. The patriotic trait, on the other hand, was included into the

Excitement dimension because of its emotional resonance.

Among all the dimensions of city brand personality,

Sincerity and

Prosocial Attitude seem to fit best into the concept of sustainability which, in accordance with the 2030 Agenda [

19], sensitizes city authorities to issues concerning people/residents and their needs, as well as the quality of the environment in which they live. The

Sincerity dimension integrates city traits connected to sensitivity to the living conditions of inhabitants while the

Prosocial Attitude dimension determines whether a city uses the formal or participatory style of preventing and dealing with problems connected to sustainable development.

The analysis of the material gathered from official Facebook accounts of Polish and Ukrainian cities provided with the role of regional capitals shows that their brands in the communication process via a social medium are based on various types of personality. In case of Polish cities, the dominating brand personality dimensions are Sincerity and Excitement, while Ukrainian cities more frequently conduct communication based on the Sincerity and Competence dimensions. When it comes to brand personality traits, the posts of Polish cities were most often qualified as: imaginative (20.3%), cheerful (14.0%), and down-to-earth (13.8%). Ukrainian cities, on the other hand, were typified as: down-to-earth (19.5%), reliable (14.7%), and patriotic (8.5%). This is the result of the fact that the communication styles of Polish cities are based upon good emotions and goodwill, while Ukrainian cities base their communiqués on everyday problems, showing their competence and emotions fitting the context of the patriotic trait.

It should be emphasized that the two new traits (bureaucratic, cooperative) were relatively frequently observed in Ukrainian posts. This can be associated both with the culture of contemporary Ukraine (and can be treated as a culture specific trait [

79]) and its imperfections with regard to the functioning of local administration.

The utilization of the quantitative method allowed for the determination of statistically significant differences between Poland and Ukraine in regard to dimensions of brand personalities presented in posts of cities from both countries. The variances were recorded in respect to the Sincerity, Excitement, Sophistication, and Prosocial Attitude dimensions. Additionally, a number of more exact differences between the two countries were noticed in the analyzed posts.

The messages included in Ukrainian posts are of a vividly formal character. Their content is of considerable length, whereas photographs and videos often contain information unattractive to a standard recipient. The posts published by Polish cities, in turn, are shorter and expressed more clearly. Photographs and videos are of much better quality and present more picturesque places from the area of a given city. The style of communication is considerably less formal.

The qualitative assessment of posts fosters the identification of the strategies used by Polish cities as territorial branding focusing on a geographic area, while the strategies of Ukrainian cities can be considered to be democracy building or one of addressing potential local voters through communicating the activities of local authorities.

The conducted research, based on qualitative studies, provides a ground for the proposal of a research hypothesis concerning the relation between the public management model and city brand personality which states that the more the model is based on the market and cooperation (NPM/NPG), the more a city brand personality is defined by attributes related to sustainability, those oriented at caring for people and their environment. This hypothesis, upon certain refinement, can become the subject of further quantitative studies.

City branding is becoming an increasingly popular governance practice; hence, the literature on the subject suggests an appeal that more studies are needed in order to fully understand the institutions and practices of urban governance in relation to city branding [

36,

74]. This study and its results address this appeal. The results of the above studies may be useful for municipalities not only from Poland and Ukraine, but also from other CEE countries. Through the use of the scale based on the extended range of brand personality dimensions and traits presented in this paper, the cities’ marketers will be able to determine how their city is perceived in relation to competing cities. The results could become an inspiration to build a distinctive city brand positioning which contributes to the creation of a recognizable city brand.

One of the limitations of this study is associated with a subjective evaluation of posts by coders which the authors attempted to minimize with the use of certain, earlier accepted, coding procedures. Moreover, the diversified publishing frequency of the analyzed posts and the assumed system of evaluating 50 posts for each city has led to analyzing periods of various lengths which could affect the contents of messages as well as their evaluation. For a number of cities, for instance, where the frequency of published posts was lower, the timeframe encompassed the period of Christmas which could result in a relatively larger number of posts referring to the issue of family (Sincerity) or strong emotions (Excitement).

The authors recommend carrying out further studies related to the expansion of the Aaker scale in relation to cities from different countries which communicate with their inhabitants through social media. It could be particularly interesting to arrive at studies which include cities from countries where democracy and free market have been a standard policy for a long time and where the public administration has adopted management models more broadly, based on the competitive and inclusionary approach (NPM/NPG models).