Cross-Sector Collaboration in Higher Education Institutions (HEIs): A Critical Analysis of an Urban Sustainability Development Program

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Background: Cross-Sector Partnerships at the Heart of Normative Debates about University Reform in the Context of Education for Sustainable Development

3. Theoretical and Methodological Orientation

3.1. Constant Comparative Approach Based on Grounded Theorizing

3.2. Sensemaking

4. Methods

4.1. Case Selection

4.2. Data Collection

4.3. Data Analysis: Open Coding and Focused Coding

5. Findings

5.1. Malmö: A Story of Collaborative Transformation of an Industrial City to a Sustainable KNOWLEDGE City

5.2. From “Center” to “Institute”: Continuously Institutionalizing Collaboration between University and Administration

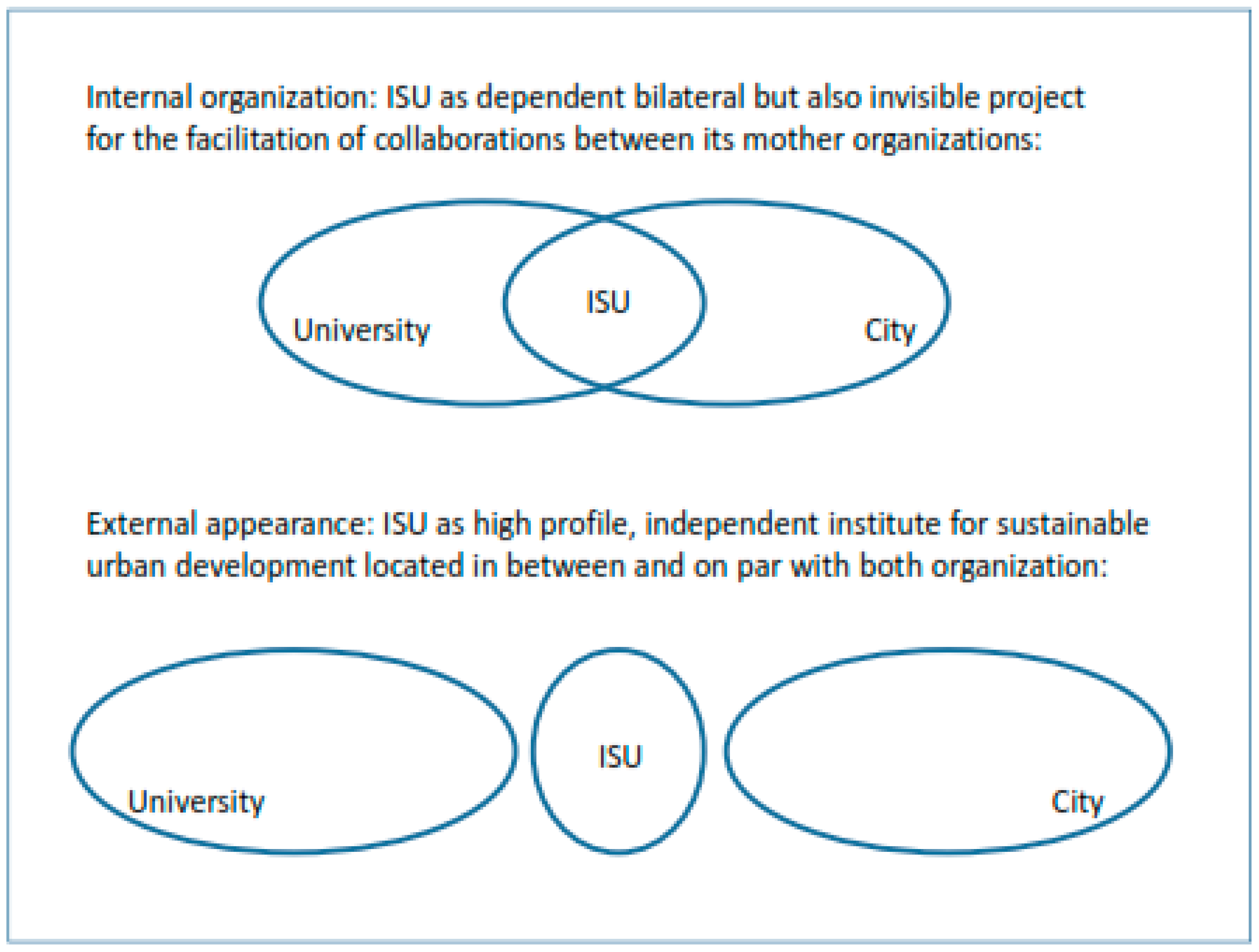

5.3. Organizing the Cross-Sector Partnership

“And ISU is, I think regarded by us (…) as a rather neutral area. So, if in the Board we often say: ‘Let’s leave this to ISU’, I think we are at the same time saying that this is a question of common interest and no one has the leading part, not the university, nor the city (…)”.(DD P29)

“I was not taking part of bringing forward the boundary agent concept. It was put on my lap and I had to take care of it, but I didn’t like the framework or the lack of framework I should say. But I should just take care of it and I should just fix it. The Board was like: ‘But you are the director, you should do this ‘—’Yes, but what did you want?’—And nobody was there either. (…) I should just fix it and then the boundary agents, that have been assigned, also come to me and ask: ‘What are we gonna do? ‘—’I don’t know what you should do’”.(BM P237)

“I think we, when we started this project, the purpose was kind of vague, what we were supposed to do. So, we developed that purpose ourselves, after trying, discussing, thinking about it a lot in our group. And we have a really interesting collaboration and a good collaboration in this boundary agent group, which I think makes us a very strong entity.”.(IR P36)

“I was considering if I want to continue already. This is mainly where I felt there was no common picture. We—as in [the director] as one unit, the steering board as one unit, the boundary agents as one unit—have no common idea, vision, what do we want to do with ISU, how do we get there? (…) It has happened that from the steering committee’s side suddenly it’s like: ‘No, this is not at all what you’re supposed to do!’ And then we do not get an explanation what is it they expect from us”.(QY P404)

“I would like to become better in how to lead without being a boss. Because, I have to lead but when you are not somebody’s boss, it is extremely difficult to lead and to get the person to do something that you want them to do when you are not their boss and you actually don’t have anything to say about them, but it is a part of your work task to lead”.(BM P172)

“You can also see how ISU was working depending on who has been the director of ISU. For example, the first we had this woman [who] was very much involved in building ISU as a sort of independent institution (…) that was more or less independent of these networks inside the university and city administration. It had a life of its own. (…) But on the other hand, we had an organization that from an organizational point of view was working quite well. But no one—even I, who was sitting in the board—knew what was going on. And then we changed the director, so now we have a director with more broker competences (…). She has a very good competence to work in networks, to connect different people with each other and so on”.(ONG P96–98)

“The group [of the boundary agents] is very strong, and [the director] is kind of lonely because she’s the only one sitting, working in ISU. And we are connected to ISU but we are not working inside of ISU, and I think that also makes it a bit difficult”.(IR P36)

“I see ISU and all the activities that ISU does as instruments to make people to get together and talk, to establish links and mutual interests and even friendships and that those connections in themselves should work in the future. So, one of the goals of ISU should be, I don’t know if that would happen, but to make itself superfluous in a way, that it shouldn’t have to be, because connections are already there.”.(JA P85)

5.4. Advantages and Disadvantages of the Fuzzy Profile between Project, Organization and Network

“There is also a strong belief that the ISU’s profile has been too fuzzy. It has not been sufficiently clear what ISU stands for and what role it should play. Some say that this is linked to ISU having become too inward-looking. The institute has marketed itself badly. Another factor may be that the concept of an institute creates expectations for something bigger than what you can live up to my opinion”.([76]-own translation)

“I mean, sustainable urban development, it’s a huge area and I think it’s important for ISU to have a red thread in what we are doing, because it’s easy that you try to work with everything within this area and then nothing will be done of relevance. (…) You have to be very strict on what you’re doing. So, you have to learn to say: ‘No, ISU can’t do this. We are focusing on these questions and will be doing so for another year’, or something like that”.(DD P79–81)

“I don’t think you can manage the expectations, actually, because people see us as a kind of a meeting place—‘Can’t this be something for ISU?’, etc.—not realizing that the personal resources are very short. And so, we have a discussion within the board almost every meeting saying: ‘Are we doing the right things and how does this new task connect to the others? Is it something ISU should be doing or is it something we could leave to other partners?”.(DD P85)

“We are valuable because we are neutral. We are not the city and we are not the university, so therefore we are not dangerous or a competitor. (…) We are just a neutral platform and we give away so much for free. We are like a consultant firm they don’t have to pay”.(BM P164–166)

“You could say the main organization or mother organizations they want, they need this organization between, and they want it to be effective and have a high profile, but not too effective and not too high profile. Because suddenly it might be competing with the mother organizations, so it’s a balance, always a balance for these types of cross board organizations. And they will always be questioned in the aims and goals and results. That is, I think, built in to the logic in itself”.(ID P65)

“When you are a group of people you have to work with your own identity, that’s natural. But it very fast becomes a risk to become an irritation for the mother organizations. (…) This is a very important question, I think: How do you secure the commitment of the mother organizations and support from the mother organizations and at the same time, develop the inner life of this organization that it can keep the people that are working here and it gets a known profile and momentum?”.(ID P77)

5.5. Employing the Fuzzy Profile by Focusing on Learning and Critical Thinking—The Urban Research Day and the Thesis Program/Urban Strategic Forum

“Targeting these actors that are not normally included in this process, in that way, ISU has kind of provided a parallel, to a certain extent, to the administrative space provided by the municipality. Or, to the academic spaces provided by the university. So, a kind of middle ground. And inviting non-expected agents into this dialogue, it’s become political”.(LGQ P120)

“It is extremely key I think, to have these kinds of open platforms, which are not instrumentally targeted towards funding, towards specific goals, or specific impact criteria, whatever. ISU should be much more open. And it’s important because we don’t know what will be the issues in two years’ time. And we need these platforms where we can come together and not react to other people’s preformulated questions and so on, but actually formulate our own questions.”.(LGQ P138)

“If the intention with ISU is to develop new project and then to be some kind of breeding ground/place that breeds new projects, then ISU should have a kind of venture fund or time fund (…). Because there’s a problem in finding time for sitting down and developing ideas. And (…) it’s also some kind of risk, because maybe you’re sitting together and you’re doing a couple of workshops and then everything ends up in nothing, because lots of ideas won’t come together, because they’re too complicated and when (…) analyze it you discover: ‘it will not work’”.(LI 33)

6. Discussion and Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Perry, B.; May, T. Urban knowledge exchange: Devilish dichotomies and active intermediation. Int. J. Knowl.-Based Dev. 2010, 1, 6–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wyatt, S.; Siune, K.; Marcus, E.; Calloni, M.; Felt, U.; Gorski, A.; Grunwald, A.; Rip, A.; Semir, V.D. Challenging Futures of Science in Society, Emerging Trends and Cutting-Edge Issues; EU: Brussels, Belgium, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Feldman, M.P.; Florida, R. The Geographic Sources of Innovation: Technological Infrastructure and Product Innovation in the United States. Ann. Am. Assoc. Geogr. 1994, 84, 210–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Etzkowitz, H.; Leydesdorff, L. The Dynamics of Innovation: From National Systems and “Mode 2” to a Triple Helix of University–Industry–Government Relations. Res. Policy 2000, 29, 109–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carayannis, E.G.; Campbell, D.F.J. Mode 3 Knowledge Production in Quadruple Helix Innovation Systems; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Torugsa, N.; O’Donohue, W. Progress in innovation and knowledge management research: From incremental to transformative innovation. J. Bus. Res. 2016, 69, 1610–1614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, T.M.V.; Dahiya, B. Smart Economy in Smart Cities. In Smart Economy in Smart Cities: International Collaborative Research: Ottawa, St. Louis, Stuttgart, Bologna, Cape Town, Nairobi, Dakar, Lagos, New Delhi, Varanasi, Vijayawada, Kozhikode, Hong Kong; Kumar, T.M.V., Ed.; Springer: Singapore, 2017; pp. 3–76. [Google Scholar]

- Hardy, C.; Phillips, N.; Lawrence, T.B. Resources, Knowledge and Influence: The Organizational Effects of Interorganizational Collaboration. J. Manag. Stud. 2003, 40, 321–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- George, G.; Zahra, S.A.; Wood, D.R. The effects of business—University alliances on innovative output and financial performance: A study of publicly traded biotechnology companies. J. Bus. Ventur. 2002, 17, 577–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perkmann, M.; Tartari, V.; McKelvey, M.; Autio, E.; Broström, A.; D’Este, P.; Fini, R.; Geuna, A.; Grimaldi, R.; Hughes, A.; et al. Academic engagement and commercialisation: A review of the literature on university—Industry relations. Res. Policy 2013, 42, 423–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simeone, L. Design Moves. Translational Processes and Academic Entrepreneurship in Design Labs; Malmö Universitet: Malmø, Sweden, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Walsh, L.; Kahn, P. Collaborative Working in Higher Education. The Social Academy; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Benneworth, P.; Conway, C.; Charles, D.; Humphrey, L.; Younger, P. Characterising Modes of University Engagement with Wider Society. A Literature Review and Survey of Best Practice; Final Report, 10th June 2009; Newcastle University: Newcastle upon Tyne, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Bikard, M.; Murray, F.; Gans, J.S. Exploring trade-offs in the organization of scientific work: Collaboration and scientific reward. Manag. Sci. 2015, 61, 1473–1495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polanyi, M. The republic of science: Its political and economic theory. Minerva 2000, 38, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olsen, J.P.; Maassen, P. European debates on the knowledge institution: The modernization of the university at the European level. In University Dynamics and European Integration; Maassen, P., Olsen, J.P., Eds.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2007; pp. 3–22. [Google Scholar]

- Reale, E.; Primeri, E. The Transformation of University Institutional and Organizational Boundaries; Sense Publishers: Rotterdam, The Netherlands; Boston, MA, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Schneidewind, U. Nachhaltige Wissenschaft. Plädoyer für Einen Klimawandel im Deutschen Wissenschafts- und Hochschulsystem [Sustainable Science. Plea for Climate Change in the German Science and Higher Education System]; Metropolis: Marburg, Germany, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Doberneck, D.M.; Glass, C.R.; Schweitzer, J. From rhetoric to reality: A typology of publically engaged scholarship. J. High. Educ. Outreach Engagem. 2010, 14, 5–35. [Google Scholar]

- Weerts, D.J. The university and urban revival: Out of the Ivory Tower and into the streets. Rev. High. Educ. 2008, 31, 523–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKelvey, M.; Holmén, M. Learning to Compete in European Universities: From Social Institution to Knowledge Business; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- McGregor, S.L.T.; Volckmann, R. Transversity. Transdisciplinary Approaches in Higher Education; Integral Publishers: Tucson, AZ, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- D’Andrea, V.; Gosling, D. Improving Teaching and Learning. A Whole Institution Approach; Society for Research into Higher Education & Open University Press: Maidenhead, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Ibáñez-Carrasco, F.; Riaño-Alcalá, P. Organizing community-based research knowledge between universities and communities: Lessons learned. Community Dev. J. 2011, 46, 72–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reason, P.; Bradbury, H. Handbook of Action Research. Participative Inquiry and Practice; SAGE Publications: London, UK, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Stringer, E.T. Action Research, 4th ed.; SAGE Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Zuber-Skerritt, O. Action Leadership. Towards a Participatory Paradigm; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Greenwood, D.J.; Levin, M. Introduction to Action Research. Social Research for Social Change, 2nd ed.; SAGE Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Hajer, M.A.; Wagenaar, H. Deliberative Policy Analysis. Understanding Governance in the Network Society; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Fischer, F. Reframing Public Policy. Discursive Politics and Deliberative Practices; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Aboelela, S.W.; Larson, E.; Bakken, S.; Carrasquillo, O.; Formicola, A.; Glied, S.A.; Haas, J.; Gebbie, K.M. Defining interdisciplinary research: Conclusions from a critical review of the literature. Health Serv. Res. 2007, 42, 329–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubb, S.; Howard, T. Linking Colleges to Communities: Engaging the University for Community Development; The Democracy Collaborative at the University of Maryland: College Park, MD, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Calhoun, C. The university and the public good. Thesis Elev. 2006, 84, 7–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marginson, S. Putting “public”back into the public university. Thesis Elev. 2006, 84, 44–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jörke, D. Bürgerbeiteiligung in der Postdemokratie. APuZ 2011, 1–2, 13–18. [Google Scholar]

- Boltanski, L.; Chiapello, E. The New Spirit of Capitalism. Int. J. Politics Cult. Soc. 2005, 18, 161–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swyngedouw, E. Designing the Post-Political City and the Insurgent Polis; Bedford Press: London, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Normand, R. The Changing Epistemic Governance of European Education. The Fabrication of the Homo Academicus Europeanus? Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Swyngedouw, E. Governance Innovation and the Citizen: The Janus Face of Governance-beyond-the-State. Urban Stud. 2005, 42, 1991–2006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ankrah, S.; Al-Tabbaa, O. Universities—Industry collaboration: A systematic review. Scand. J. Manag. 2015, 31, 387–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldkuhl, G.; Cronholm, S. Adding Theoretical Grounding to Grounded Theory: Toward Multi-Grounded Theory. Int. J. Qual. Methods 2010, 9, 187–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glaser, B.; Strauss, A.L. Discovery of Grounded Theory. Strategies for Qualitative Research, 1st ed.; Taylor and Francis: Somerset, UK, 1967. [Google Scholar]

- Merton, R.K. On Sociological Theories of the Middle Range 1949. In Social Theoryand Social Structure; The Free Press: New York, NY, USA, 1949. [Google Scholar]

- Geels, F.W. Feelings of Discontent and the Promise of Middle Range Theory for STS. Sci. Technol. Hum. Values 2007, 32, 627–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hedström, P.; Ylikoski, P.K. Analytical Sociology and Rational Choice Theory. In Analytical Sociology: Actions and Networks; Manzo, G., Ed.; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2014; pp. 57–70. [Google Scholar]

- Corbin, J.M.; Strauss, A.L. Basics of Qualitative Research. Techniques and Procedures for Developing Grounded Theory, 4th ed.; SAGE: Los Angeles, CA, USA; London, UK; New Delhi, India; Singapore; Washington, DC, USA; Boston, MA, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Fram, S.M. The Constant Comparative Analysis Method Outside of Grounded Theory. Qual. Rep. 2013, 18, 1–25. [Google Scholar]

- Charmaz, K. Constructing Grounded Theory, 2nd ed.; SAGE: London, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Weick, K.E. Sensemaking in Organizations; SAGE Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor, J.R.; van Every, E.J. The Emergent Organization: Communication as Its Site and Surface; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Strauss, A.L. A social world perspective. Stud. Symb. Interact. 1978, 1, 119–128. [Google Scholar]

- Volbers, J. Theorie und Praxis im Pragmatismus und in der Praxistheorie. In Praxis Denken; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2015; pp. 193–214. [Google Scholar]

- Latour, B. The Powers of Association. Sociol. Rev. 1984, 32, 264–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruner, J. The Narrative Construction of Reality. Crit. Inq. 1991, 18, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamberelis, G.; Dimitriadis, G. Focus Groups. From Structured Interviews to Collective Conversations; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Barbour, R.S. Analyising Focus Groups. In The SAGE Handbook of Qualitative Data Analysis; Flick, U., Ed.; SAGE Publications: London, UK, 2013; pp. 313–326. [Google Scholar]

- Vogl, S. Gruppendiskussion [Group discussion]. In Handbuch Methoden der Empirischen Sozialforschung [Manual Methods of Empirical Social Research]; Baur, N., Blasius, J., Eds.; Springer VS: Wiesbaden, Germany, 2014; pp. 581–596. [Google Scholar]

- Flick, U. An Introduction to Qualitative Research; SAGE: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Kidd, P.S.; Parshall, M.B. Getting the focus and the group: Enhancing analytical rigor in focus group research. Qual. Health Res. 2000, 10, 293–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgan, D.L. Focus Groups as Qualitative Research; SAGE Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Morgan, D.L. Focus Groups. Annu. Rev. Sociol. 1996, 22, 129–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creswell, J.W. Research Design. Qualitative, Quantitative, and Mixed Methods Approaches, 4th ed.; SAGE: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- SEKUM. Fran Sekum Till ISU [From Sekum to ISU]; [internal programm document]; SEKUM: Malmö, Sweden, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- ISU. Verksamhetsplan 2014; [internal programm document]; ISU: Malmö, Sweden, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Ryan, G.W.; Bernard, H.R. Techniques to identify themes. Field Methods 2003, 15, 85–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saldaña, J. The Coding Manual for Qualitative Researchers; SAGE: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Palmberger, M.; Gingrich, A. Qualitative Comparative Practices: Dimensions, Cases and Strategies. In The SAGE Handbook of Qualitative Data Analysis; Flick, U., Ed.; SAGE Publications: London, UK, 2013; pp. 94–108. [Google Scholar]

- ISU. Årsrapport 2013 [Annual Report 2013]; ISU: Malmö, Sweden, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Holgersen, S. The Rise (and Fall?) of Post-Industrial Malmö. Investigations of City-Crisis Dialectics; Department of Human Geography, Lund University: Lund, Sweden, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- SEKUM. Minnesanteckningar fran SEKUMs visionsdag 19-11-2003; [Internal Minutes from SEUMs vision day]; SEUM: Malmö, Sweden, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson, T. Malmo: A city in transition. Cities 2014, 39, 10–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Öquist, G.; Benner, M. Why are some nations more successful than others in research impact? A comparison between Denmark and Sweden. In Incentives and Performance: Governance of Research Organizations; Welpe, I.M., Wollersheim, J., Ringelhan, S., Osterloh, M., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2015; pp. 241–257. [Google Scholar]

- SEKUM. Minnesanteckningar fran SEKUM 16.03.2003; [Internal Minutes]; SEKUM: Malmö, Sweden, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- SEKUM. Verksamhetsplan och Budgetunderlag 2005 [Business Plan and Budget Basis 2005]; [internal programm document; SEKUM: Malmö, Sweden, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- SEKUM. Minnesantekningar fran SEKUM [Minutes from SEKUM]; [internal minutes]; SEKUM: Malmö, Sweden, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Persson, B. ISU—Institutet för Hållbar Stadsutveckling—Utvärdering av Verksamhetens tre Första år. [ISU—Institute for Sustainable Urban Development—Evaluation of the Business’s First Three Years]; Larki Lund: Lund, Sweden, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Persson, C. Institutet för Hållbar Stadsutveckling—Förslag Till Framtida Verksamhet [Institute for Sustainable Urban Development—Proposal for Future Activities]; ISU—Institutet för Hållbar Stadsutveckling: Malmö, Sweden, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- ISU. Årsrapport 2013; [internal programm document]; ISU: Malmö, Sweden, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- ISU. Strategiskt Basdokument 2012 [Strategic Basic Document 2012]; ISU: Malmö, Sweden, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- ISU. Verksamhetsplan 2014 [Business Plan 2014]; ISU: Malmö, Sweden, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Weick, K.E.; Sutcliffe, K.M.; Obstfeld, D. Organizing and the process of sensemaking. Organ. Sci. 2005, 16, 409–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, M. Landkarten der Narrativen Therapie [Narrative Therapy Maps]; Carl-Auer-Verlag: Heidelberg, Germany, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Gavazzi, S.M.; Fox, M. Understanding campus and community relationships through marriage and family metaphors: A town-gown typology. Innov. High. Educ. 2014, 39, 361–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Picione, R.D.L.; Valsiner, J. Psychological functions of semiotic borders in sense-making: Liminality of narrative processes. Eur. J. Psychol. 2017, 13, 532–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Picione, R.D.L.; Freda, M.F. Borders and modal articulations. Semiotic constructs of sensemaking processes enabling a fecund dialogue between cultural psychology and clinical psychology. Integr. Psychol. Behav. Sci. 2016, 50, 29–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Mehling, S.; Kolleck, N. Cross-Sector Collaboration in Higher Education Institutions (HEIs): A Critical Analysis of an Urban Sustainability Development Program. Sustainability 2019, 11, 4982. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11184982

Mehling S, Kolleck N. Cross-Sector Collaboration in Higher Education Institutions (HEIs): A Critical Analysis of an Urban Sustainability Development Program. Sustainability. 2019; 11(18):4982. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11184982

Chicago/Turabian StyleMehling, Sebastian, and Nina Kolleck. 2019. "Cross-Sector Collaboration in Higher Education Institutions (HEIs): A Critical Analysis of an Urban Sustainability Development Program" Sustainability 11, no. 18: 4982. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11184982

APA StyleMehling, S., & Kolleck, N. (2019). Cross-Sector Collaboration in Higher Education Institutions (HEIs): A Critical Analysis of an Urban Sustainability Development Program. Sustainability, 11(18), 4982. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11184982