‘A Nut We Have Officially yet to Crack’: Forcing the Attention of Athletic Departments Toward Sustainability Through Shared Governance

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Research Context

2.1. Sustainability Management in Higher Education

2.2. Sustainability Management in Intercollegiate Athletics

3. Theoretical Background

3.1. Loosely Coupled Systems

…loose coupling allows theorists to posit that any system, in an organizational location, can act on both a technical level, which is closed to outside forces (coupling produces stability), and an institutional level, which is open to outside forces (looseness produces flexibility).(p. 205)

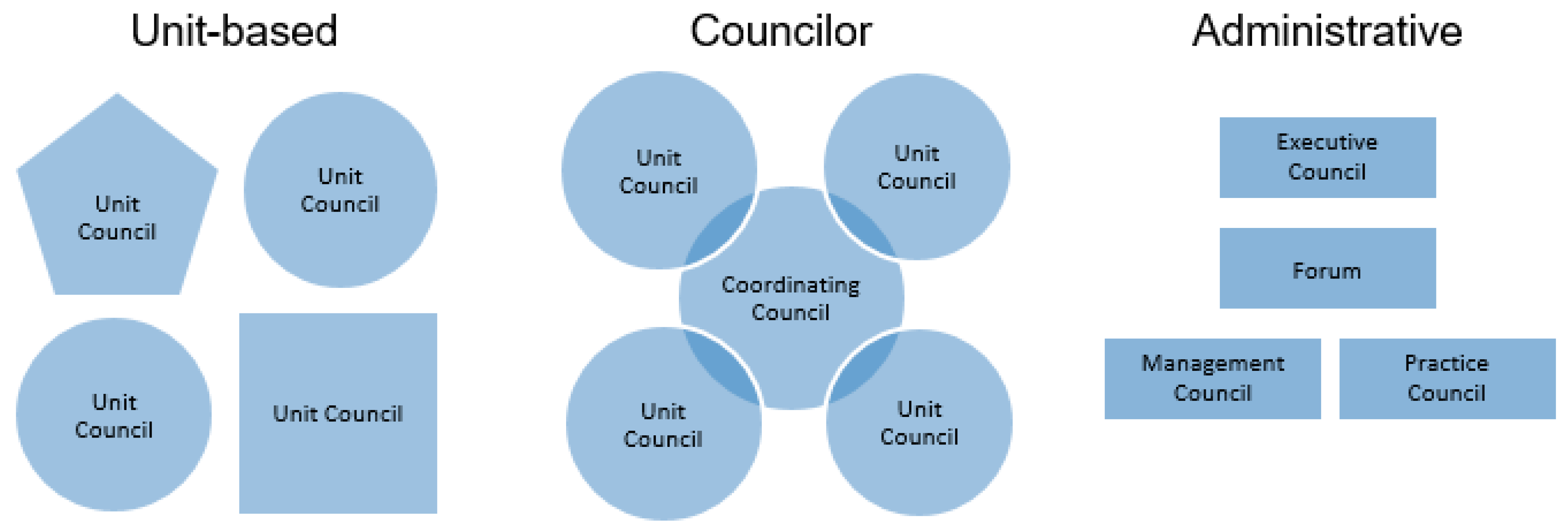

3.2. Shared Governance as a Compensation for Loose Coupling

4. Methods

4.1. Research Design

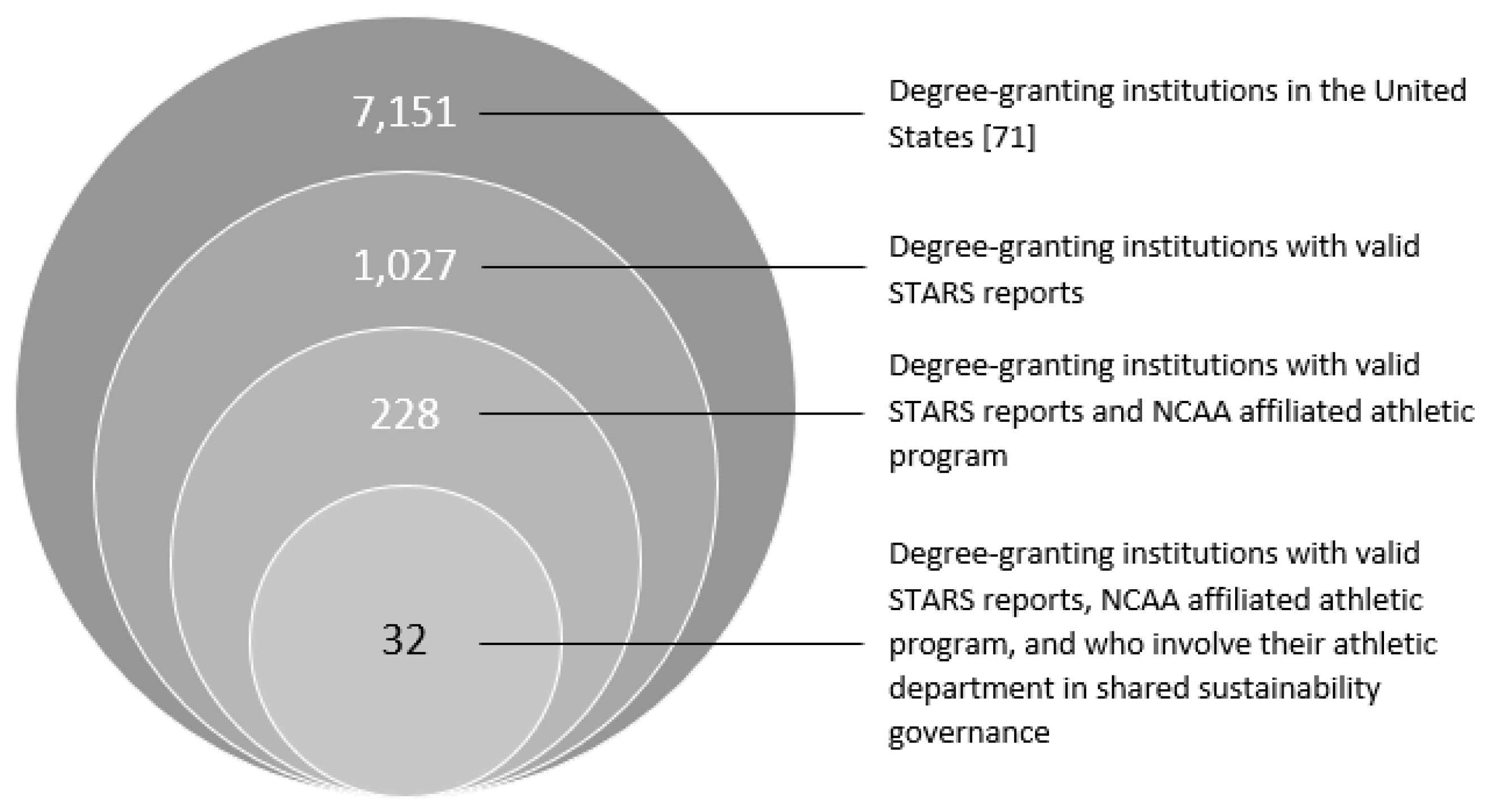

4.2. Study Population

4.3. Data Collection

4.4. Data Analysis

5. Findings and Discussion

5.1. Engaging Athletics in Shared Sustainability Governance

It’s primarily staff, facilities, campus planning and development, academic affairs, so the deans of all of the colleges on campus or their designate is represented, and then a representative from housing and residential life, and then those students who are designate environmental senators serve on the committee along with a handful of other students that have various roles on campus.

I liken this to a job I had in the private sector where we were committed to sustainability, but it didn’t have a face until we tied it to one of the more popular products. Once we tied sustainability to athletics that gave us a front door to open conversations with a number of different stakeholders.

Athletics has two primary areas where they overlap with sustainability—one is greenhouse gas emissions, and the other is materials.… So by engaging the Athletics Director we are reaching an important subset of campus that is having an impact in those sustainability areas.

So we did have someone within athletics two years ago who had more experience working with green athletic programs at other universities. He helped us to implement green soccer games, we connected him with our composting and catering on campus, and worked really hard to make sure there was as little waste at games as possible.

5.2. Shared Sustainability Governance as a Compensation for Loose Coupling

A lot of times athletics can feel like its own separate world because they are funded differently and all that. But they are still a part of the university. So I think having them be a part of a larger sustainability committee helps them realize being bold and savvy should translate over to athletics as well.

We understand athletics has special needs and concerns, but we might not fully understand what those concerns are. So to have them at the table, it’s great. So for example, just turf, our baseball fields are turf. So for sustainability it reduces water I guess and pesticide use because it’s not real grass. But that wasn’t their only reason for getting it, it was because we can’t compete with southern schools because it’s cold and shitty, you know, up here in spring. So we have to have artificial turf in order for our fields not to flood.

Perhaps there may be an actual reason why the stadium lights are on all night long and there’s no game. Maybe there’s an actual reason. Like they’re doing construction in there or something like that. And those kind of things come up in meeting and people were actually getting an answer, and they were like ‘Right. OK. That makes sense.’

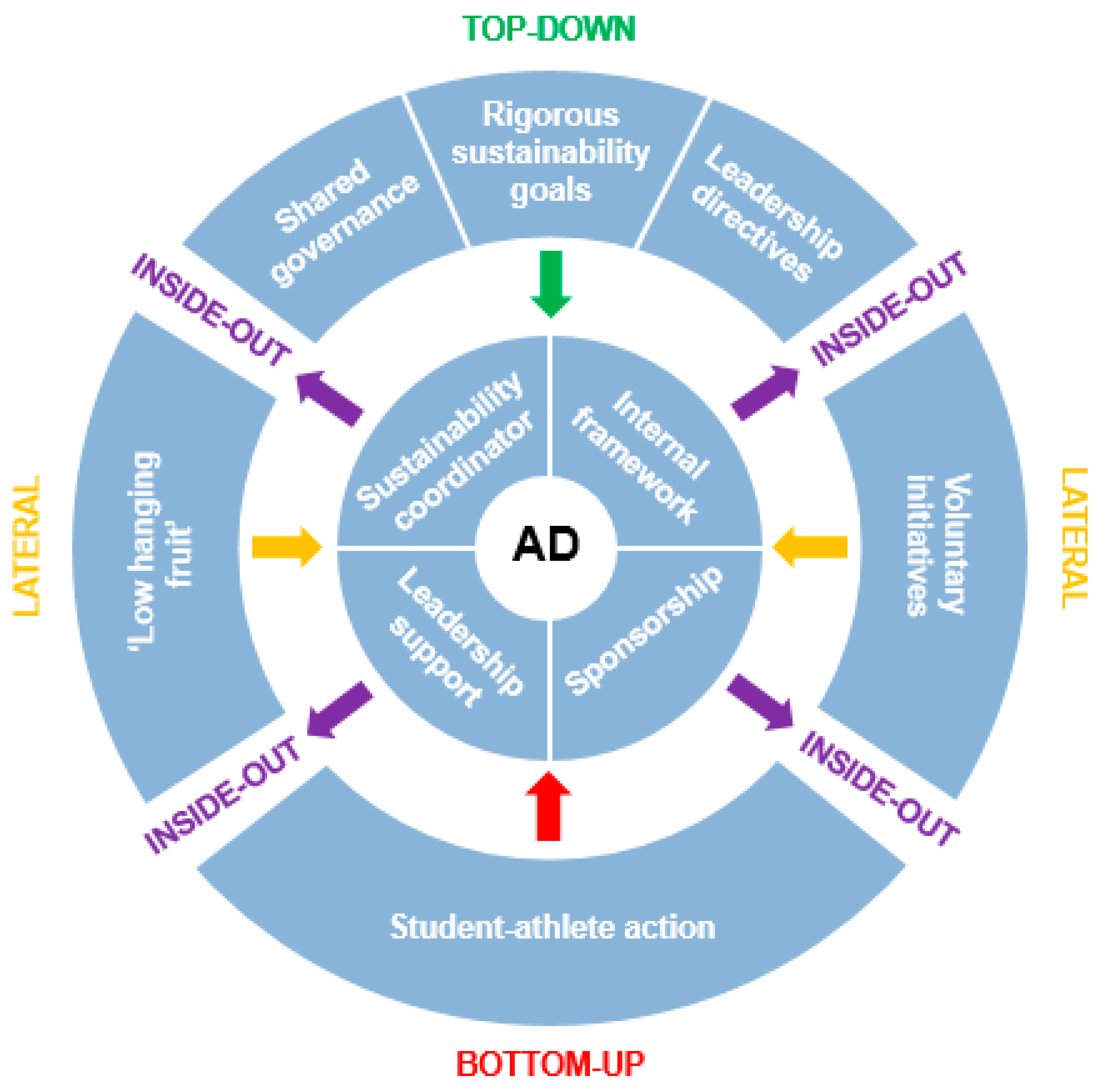

5.3. ‘A Perfect Storm’: Supplementing Shared Sustainability Governance

They see the benefit, but I think it’s still at the point where we’re making them do something. So I think it’s been a long time where I think that’s where we’re perceived as we’re telling them to do something rather than working with them.

5.4. Limitations of the Study

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Krizek, K.J.; Newport, D.; White, J.; Townsend, A.R. Higher education’s sustainability imperative: How to practically respond? Int. J. Sustain. High. Educ. 2012, 13, 19–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reponen, T. Is leadership possible at loosely coupled organizations such as universities? High. Educ. Policy 1999, 12, 237–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD. Changing patterns of governance in higher education. In Education Policy Analysis; OECD: Paris, France, 2003; Available online: https://www.oecd.org/education/skills-beyond-school/35747684.pdf (accessed on 12 September 2019).

- Orton, J.D.; Weick, K.E. Loosely coupled systems: A reconceptualization. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1990, 15, 203–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, J.W.; Rowan, B. The structure of educational organizations. In Schooling in a Social Context, 3rd ed.; Ballantine, J.H., Spade, J.Z., Eds.; Pine Forge Press: Lose Angeles, CA, USA, 2008; pp. 217–226. [Google Scholar]

- Hardy, C.; Langley, A.; Mintzberg, H.; Rose, J. Strategy formation in the university setting. Rev. High. Educ. 1983, 6, 407–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birnbaum, R. How Academic Leadership Works; Jossey-Bass: San Francisco, CA, USA, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Blackburn, R.T.; Lawrence, J.H. Faculty at Work; The John Hopkins Press: Baltimore, MD, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Del Favero, M.; Bray, N.J. Herding cats and big dogs: Tensions in the faculty-administrator relationship. In Higher Education: Handbook of Theory and Research; Paulsen, M.B., Perna, L.W., Eds.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2010; Volume 25. [Google Scholar]

- Peterson, M.W.; White, T.H. Faculty and administrator perceptions of their environments: Different views of different models of organization? Res. High. Educ. 1992, 33, 177–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandler, J.C., III. Bridging the Chasm: Emerging Model of Leadership in Intercollegiate Athletics Governance. Ph.D. Theis, The University of Las Vegas Nevada, Las Vegas, NV, USA, December 2011. Available online: https://digitalscholarship.unlv.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?referer=https://scholar.google.com/&httpsredir=1&article=2375&context=thesesdissertations (accessed on 12 September 2019).

- Hanford, G.H.; Greenberg, M. We should speak the “awful truth” about college sports…or does the public like the status quo? Chron. High. Educ. 2003, 49, 10–13. [Google Scholar]

- Sack, A.L. College sport and the student athlete. J. Sport Soc. Issues 1987, 11, 31–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suggs, W. Old challenges and new opportunities for studying the financial aspects of intercollegiate athletics. N. Dir. High. Educ. 2009, 148, 11–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duderstadt, J.J. Intercollegiate Athletics and the American University: A University President’s Perspective; The University of Michigan Press: Ann Arbor, MI, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Sanderson, A.R.; Siegfried, J.J. The case for paying college athletes. J. Econ. Perspect. 2015, 29, 115–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bass, J.R.; Schaeperkoetter, C.C.; Bunds, K.S. The ‘Front Porch’: Examining the Increasing Interconnection of University and Athletic Department Funding; ASHE higher education report; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2015; Volume 41. [Google Scholar]

- Casper, J.M.; Pfahl, M.E.; McSherry, M. Athletics department awareness and action regarding the environment: A study of NCAA athletics department sustainability practices. J. Sport Manag. 2012, 26, 11–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casper, J.M.; Pfahl, M.E. Environment sustainability practices in U.S. NCAA Division II athletics departments. Int. J. Event Manag. Res. 2015, 10, 12–36. [Google Scholar]

- Casper, J.M.; Pfahl, M.E.; McCullough, B.P. Intercollegiate sport and the environment: Examining fan engagement based on athletics department sustainability efforts. J. Issues Intercoll. Athl. 2014, 7, 65–91. [Google Scholar]

- Ferrer-Balas, D.; Adachi, J.; Banas, S.; Davidson, C.I.; Hoshikoshi, A.; Mishra, A.; Motodoa, Y.; Onga, M.; Ostwald, M. An international comparative analysis of sustainability transformation across seven universities. Int. J. Sustain. High. Educ. 2008, 9, 295–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, R.; Martin, S.; Boom, K. University culture and sustainability: Designing and implementing an enabling framework. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 171, 434–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asif, M.; Searcy, C.; Zutshi, A.; Fisscher, O.A.M. An integrated management systems approach to corporate social responsibility. J. Clean. Prod. 2013, 56, 7–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viebahn, P. An environmental management model for universities: From environmental guidelines to staff involvement. J. Clean. Prod. 2002, 10, 3–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, H.-D.; Rowan, B. Institutional analysis and the study of education. In The New Institutionalism in Education; Meyer, H.-D., Rowan, B., Eds.; SUNY Press: Albany, NY, USA, 2006; pp. 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- De Boer, H.F.; Enders, J.; Leisyte, L. Public sector reform in Dutch higher education: The organizational transformation of the university. Public Adm. 2007, 85, 27–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velazquez, L.; Munguia, N.; Platt, A.; Taddei, J. Sustainable university: What can be the matter? J. Clean. Prod. 2006, 14, 810–819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, C.A. Sustainability reporting and performance management in universities: Challenges and benefits. Sustain. Account. Manag. Policy J. 2013, 4, 384–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pfahl, M.E. Strategic issues associated with the development of internal sustainability teams in sport and recreation organization: A framework for action and sustainable environmental performance. Int. J. Sport Manag. Rec. Tour. 2010, 6, 37–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCullough, B.P.; Kellison, T.; Wendling, E. Formation and function of a collegiate athletics sustainability committee. J. Amat. Sport 2018, 4, 52–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISCN Secretariat. International Sustainable Campus Network (ISCN): Taking Your Campus Sustainability Program to a Global Stage. In Proceedings of the 4th UNICA Green Academic Footprint Workshop, Brussels, Belgium, 27–28 March 2014; Available online: http://www.unica-network.eu/sites/default/files/ISCN%20Overview_20140327_for%20UGAF_cg.pdf (accessed on 12 September 2019).

- Swearingen White, S. Campus sustainability plans in the United States: Where, what, and how to evaluate? Int. J. Sustain. High. Educ. 2014, 15, 228–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Second Nature. History. Available online: https://secondnature.org/history/ (accessed on 12 September 2019).

- Swearingen White, S. Early participation in the American College and University Presidents’ Climate Commitment. Int. J. Sustain. High. Educ. 2009, 10, 215–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tilbury, D. Higher education for sustainability: A global overview of commitment and progress. High. Educ. World 2011, 4, 18–28. [Google Scholar]

- Stephens, J.C.; Hernandez, M.E.; Román, M.; Graham, A.C.; Scholz, R.W. Higher education as a change agent for sustainability in different cultures and contexts. Int. J. Sustain. High. Educ. 2008, 9, 317–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hottle, T.A.; Bilec, M.M.; Brown, N.R.; Landis, A.E. Toward zero waste: Composting and recycling for sustainable venue based events. Waste Manag. 2015, 38, 86–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klein-Banai, C.; Theis, T.L. An urban university’s ecological footprint and the effect of climate change. Ecol. Indic. 2011, 11, 857–860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dmochowski, J.E.; Garofalo, D.; Fisher, S.; Greene, A.; Gambogi, D. Integrating sustainability across the university curriculum. Int. J. Sustain. High. Educ. 2016, 17, 652–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dyer, G.; Dyer, M. Strategic leadership for sustainability by higher education: The American College & University Presidents’ Climate Commitment. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 140, 111–116. [Google Scholar]

- Salvioni, D.; Franzoni, S.; Cassna, R. Sustainability in the higher education system: An opportunity to improve quality and image. Sustainability 2017, 9, 914–942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ralph, M.; Stubbs, W. Integrating environmental sustainability into universities. High. Educ. 2014, 67, 71–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Epstein, M.J. Implementing corporate sustainability: Measuring and managing social and environmental impacts. Strateg. Financ. January 2008, 25–31. [Google Scholar]

- Pfahl, M.E.; Casper, J.M.; Trendafilova, S.; McCullough, B.P.; Nguyen, S.N. Crossing boundaries: An examination of sustainability department and athletics department collaboration regarding environmental issues. Commun. Sport 2015, 3, 27–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glassman, R.B. Persistence and loose coupling in living systems. Behav. Sci. 1973, 18, 83–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bossert, S.; Dwyer, D.; Rowan, B.; Lee, G. The instructional management role of the principal. Educ. Adm. Q. 1982, 18, 34–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brusoni, S.; Prencipe, A. Managing knowledge in loosely coupled networks: Exploring the links between product and knowledge dynamics. J. Manag. Stud. 2001, 38, 1019–1035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weick, K.E. Educational organizations as loosely coupled systems. Adm. Sci. Q. 1976, 21, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldspink, C. Rehtinking educational reform: A loosely coupled and complex systems perspective. Educ. Manag. Adm. Leadersh. 2007, 35, 27–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tierney, W.G.; Minor, J.T. A cultural perspective on communications and governance. In Restructuring Shared Governance in Higher Education: New Directions for Higher Education; Tierney, W.G., Lechuga, V.M., Eds.; Jossey-Bass: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2004; pp. 85–94. [Google Scholar]

- Tricker, R.I. International Corporate Governance; Prentice Hall: Englewood Cliffs, NJ, USA, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Olson, G.A. Exactly What Is ‘Shared Governance’? The Chronicle of Higher Education: Washington, DC, USA; Available online: https://www.chronicle.com/article/Exactly-What-Is-Shared/47065 (accessed on 12 September 2019).

- Lechuga, V.M. Exploring current issues on shared governance. In Restructuring Shared Governance in Higher Education; Tierney, W.G., Lechuga, V.M., Eds.; Jossey-Bass: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2004; pp. 95–98. [Google Scholar]

- Cramer, S.F.; Mozlin, R. Sharing shared governance: The benefits of systemness. In Shared Governance in Higher Education: Demands, Transitions, Transformations; Cramer, S.F., Ed.; SUNY Press: Albany, NY, USA, 2017; pp. 89–116. [Google Scholar]

- SUNY Shared Governance Transformation Team. Preamble to Shared Governance Toolkit Guidelines. 2011. Available online: https://system.suny.edu/media/suny/content-assets/documents/powerofsuny/the-process-of-the-power-of-suny/SharedGovernance_20110408.pdf (accessed on 12 September 2019).

- Bejou, D.; Bejou, A. Shared governance and punctuated equilibrium in higher education: The case for student recruitment, retention, and graduation. J. Relatsh. Market. 2012, 11, 248–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lapworth, S. Arresting decline in shared governance: Towards a flexible model for academic participation. High. Educ. Q. 2004, 58, 299–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yanko, J.R.; Hardt, M.; Bradstock, J. The clinical nurse specialist role in shared governance. Crit. Care Nurs. Q. 1995, 18, 86–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernreuter, M. The other side of shared governance. J. Nurs. Adm. 1993, 23, 12–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hess, J.R. Shared governance: Innovation or imitation? Nurs. Econ. 1994, 12, 28–34. [Google Scholar]

- Saxton, T. The effects of partner and relationship characteristics on alliance outcomes. Acad. Manag. J. 1997, 40, 443–461. [Google Scholar]

- Asmus, D.; Griffin, J. Harnessing the power of your suppliers. McKinsey Q. 1993, 3, 63–79. [Google Scholar]

- Lawson, B.; Peterson, K.J.; Cousins, P.D.; Handfield, R.B. Knowledge sharing in interorganizational product development teams: The effect of formal and informal socialization mechanisms. J. Prod. Innov. Manag. 2009, 26, 156–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bstieler, L.; Hemmert, M.; Barczak, G. Trust formation in university-industry collaborations in the U.S. biotechnology industry: IP policies, shared governance, and champions. J. Prod. Innov. Manag. 2014, 32, 111–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anthony, M.K. Shared governance models: The theory, practice, and evidence. Online J. Nurs. Issues 2004, 9, 138–157. [Google Scholar]

- Burnside, B.; Witkin, L. Forging successful university-industry collaborations. Res.-Technol. Manag. 2008, 51, 26–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Vaus, D.A.; de Vaus, D. Research Design in Social Research; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Babbie, E. The Practice of Social Research, 13th ed.; Cengage Learning: Boston, MA, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Remler, D.K.; Van Ryzin, G.G. Research Methods in Practice: Strategies for Description and Causation; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- White, G.B.; Koester, R.J. STARS and GRI: Tools for campus greening strategies and prioritizations. Sustainability 2012, 5, 100–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NCES. Digest of Education Statistics: 2016. Available online: https://nces.ed.gov/programs/digest/d16/ch_3.asp (accessed on 12 September 2019).

- Palinkas, L.A.; Horwitz, S.M.; Green, C.A.; Wisdom, J.P.; Duan, N.; Hoagwood, K. Purposeful sampling for qualitative data collection and analysis in mixed method implementation research. Adm. Policy Ment. Health 2015, 42, 533–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrow, J.M.; Khandhar, P.B. Research Ethics. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK459281/ (accessed on 12 September 2019).

- Guest, G.; Bunce, A.; Johnson, L. How many interviews are enough? An experiment with data saturation and variability. Field Methods 2006, 18, 59–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creswell, J.W.; Plano Clark, V.L. Designing and Conducting Mixed Methods Research, 3rd ed.; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Shenton, A.K. Strategies for ensuring trustworthiness in qualitative research projects. Educ. Inf. 2004, 22, 63–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fisher, R.J. Social desirability bias and the validity of indirect questioning. J. Consum. Res. 1993, 20, 303–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saldaña, J. The Coding Manual for Qualitative Researchers; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Gigch, J.P. Applied General Systems Theory, 2nd ed.; Harper: New York, NY, USA, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Skyttner, L. General Systems Theory: Ideas and Applications; World Scientific: River Edge, NJ, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Meyer, J.W.; Rowan, B. Institutionalized organizations: Formal structure as myth and ceremony. Am. J. Sociol. 1977, 83, 340–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haas, P.M. Addressing the global governance deficit. Global Environ. Polit. 2004, 4, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newig, J.; Günther, D.; Pahl-Wostl, C. Synapses in the network: Learning in governance networks in the context of environmental management. Ecol. Soc. 2010, 15, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rio+20. People’s Sustainability Treaty on Higher Education. In Proceedings of the United Nations Conference on Sustainable Development, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 20–22 June 2012; Available online: https://sustainabilitytreaties.org/draft-treaties/higher-education/ (accessed on 12 September 2019).

- Lee, B. Campus leaders and campus senates. In Faculty in Governance: The Role of Senates and Joint Committees in Academic Decision Making; Birnbaum, R., Ed.; Jossey-Bass: San Francisco, CA, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar]

| Lever | Direction | Representative Quotation |

|---|---|---|

| Rigorous sustainability goals | Top-down | Until all sustainability is just incorporated into every single unit or until out climate commitments have some sort of teeth behind them and saying you must do it. I think the opportunity we’ve had is just applying these increasingly rigorous sustainability goals for all facilities to athletics, which sort of brings them along in a way that maybe they haven’t called out for themselves. |

| Leadership directives | Top-down | My hope would be that the department’s priorities are synced with the university’s priorities, and values, and one of those is sustainability. So it is my hope that would filter down. |

| ‘Low-hanging fruit’ | Lateral | I think there’s an interest within waste management and recycling and composting. I say that just because that’s the thing we spend the most time talking about and folks seem to get the most excited about. We do have a lot of low-hanging fruit opportunities there within that realm. So that might be one sort of focal area where I can sort of see a little bit more traction with them. |

| Voluntary initiatives | Lateral | We are also working on a program that is in-house that allows departments to sign up to make their travel carbon neutral or by helping the university to reduce greenhouse emissions through efficiency projects on campus. We are hoping that by using programs like this it will allow departments and events to advertise the fact that they are doing something that is carbon neutral and get credit for that, that will apply pressure, peer pressure. |

| Internal framework | Inside-out | I would say the responsibility of the university writ large with sustainability would be to create a culture where somebody on the inside of athletics says, ‘you know what, sustainability is really part of what we do and we need to call it out here.’ I think having a framework for them can sort of clearly define their expectations, their strategies, to make athletics more sustainable. |

| Leadership support | Inside-out | I would think it would have to be our Athletics Director wanting sustainability to be part of what they do. And that might happen through conversations with our President.… But if it became part of the leadership team and one of their goals was around sustainability, then I could imagine a greater involvement with athletics. But I think it they are going to go all in, then it’s going to take that top level leadership to say, ‘look, this is really important’. We want a culture of winning and winning games, but we’re not just winning on the field – we’re winning off the field. |

| Sustainability coordinator | Inside-out | I think it would take dedicated time from the current staff. We can help support from the outside, but with larger departments on campus there are certain sub-cultures in these departments. And so until those sub-cultures recognize sustainability as part of their daily practices, I think any change that comes from the outside will only be temporary. For the athletics department to become more sustainable and really push that, honestly it’s having someone that’s dedicated 24/7 to the operations of our athletics department. |

| Sponsorship | Inside-out | The other would be sponsorship. Nothing has come to fruition yet, but that is something that if it did happen, that would be a much easier way for athletics, especially the operations, to really make it a priority. That would be a game changer. |

| Student-athlete action | Bottom-up | Two years ago I had a student working on zero waste. They worked a lot on reducing waste and raising awareness on campus.… Our Athletics Director was engaged in that and he helped and advocated for building composting into some of the athletics events and recycling. So that connection, that student-to-director at a smaller scale and not as part of the large group was probably more impactful than coming to the large group. I think student interest goes a long, long way. And so if some of the sports teams are interested in this, saying that it is a huge problem for the future of the sport, that would go a long way. I think that goes farther than anything I can say or do as a staff member. I think on a college campus the more the student are invested in, involved in something, the better chance of success we have. |

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Barrett, M.; Bunds, K.S.; Casper, J.M.; Edwards, M.B.; Showalter, D.S.; Jones, G.J. ‘A Nut We Have Officially yet to Crack’: Forcing the Attention of Athletic Departments Toward Sustainability Through Shared Governance. Sustainability 2019, 11, 5198. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11195198

Barrett M, Bunds KS, Casper JM, Edwards MB, Showalter DS, Jones GJ. ‘A Nut We Have Officially yet to Crack’: Forcing the Attention of Athletic Departments Toward Sustainability Through Shared Governance. Sustainability. 2019; 11(19):5198. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11195198

Chicago/Turabian StyleBarrett, Martin, Kyle S. Bunds, Jonathan M. Casper, Michael B. Edwards, D. Scott Showalter, and Gareth J. Jones. 2019. "‘A Nut We Have Officially yet to Crack’: Forcing the Attention of Athletic Departments Toward Sustainability Through Shared Governance" Sustainability 11, no. 19: 5198. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11195198

APA StyleBarrett, M., Bunds, K. S., Casper, J. M., Edwards, M. B., Showalter, D. S., & Jones, G. J. (2019). ‘A Nut We Have Officially yet to Crack’: Forcing the Attention of Athletic Departments Toward Sustainability Through Shared Governance. Sustainability, 11(19), 5198. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11195198