The Regulatory Framework and Minerals Development in Vietnam: An Assessment of Challenges and Reform

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Mining Regulations in Vietnam and Beyond

2.1. Towards a Modern Mining Code

2.2. Vietnamese Mining Regulations

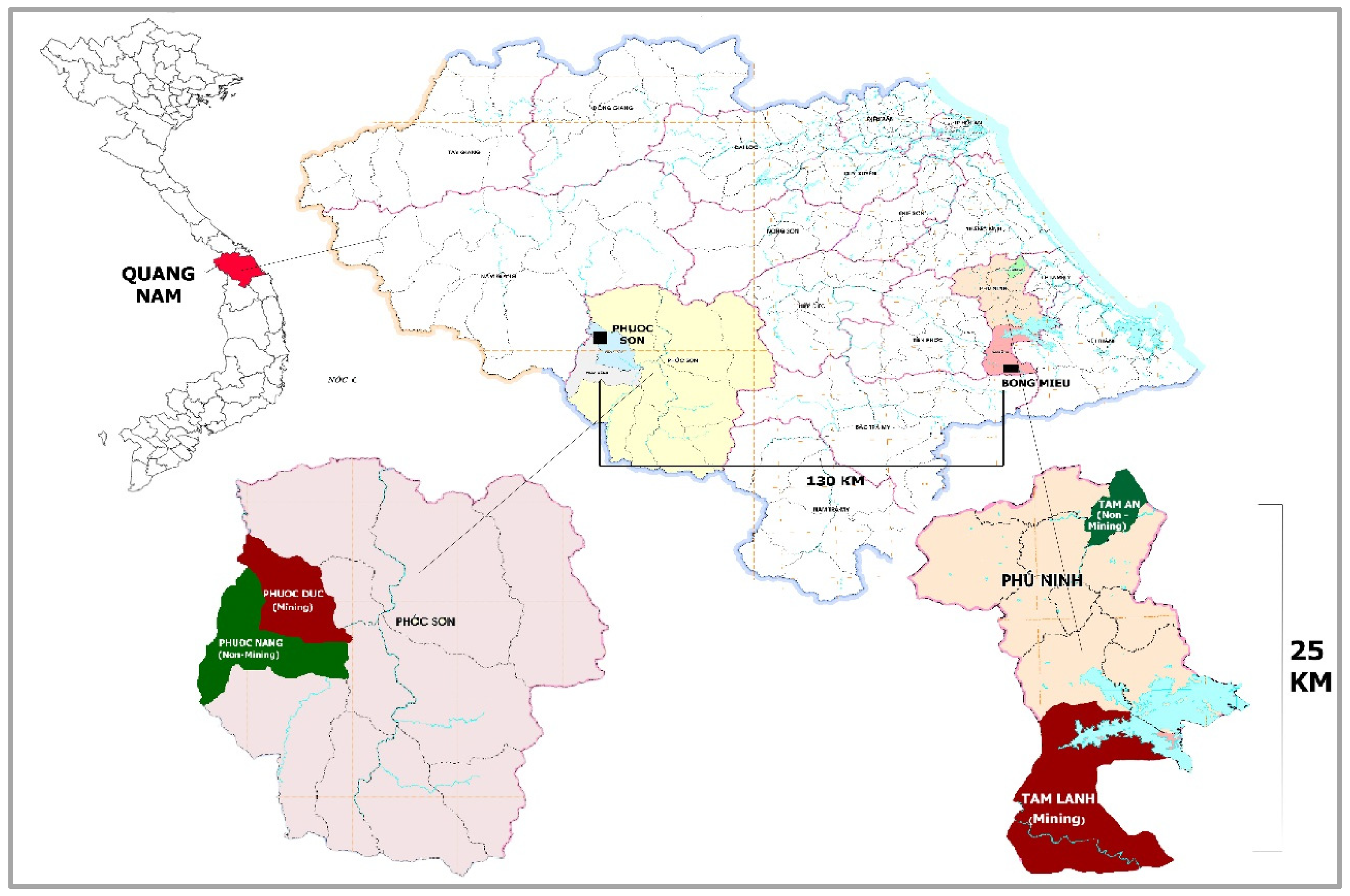

3. Methods

4. The Modern Mining Code and Regulatory Reform in Vietnam

4.1. Complexity and Inconsistency in Regulations

4.2. Licensing and Transparency

4.3. Corruption and Rent-Seeking

4.4. Tax Regulations

4.5. Environmental Protection

4.6. Societal Impacts

4.7. Improvements to Mining Regulations

5. Mining Legislation at the Local Level

5.1. Fees and Taxes

5.2. Environment and Society

5.3. Corporate Social Responsibility

6. Discussion and Conclusions

6.1. Regulatory Reform Outcomes

6.2. Limitations of the Regulatory System

6.3. Future Considerations

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Weinthal, E.; Luong, P.J. Combating The Resource Curse: An Alternative Solution To Managing Mineral Wealth. Perspect. Politics 2006, 4, 35–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bebbington, A.; Hinojosa, L.; Bebbington, D.H.; Burneo, M.L.; Warnaars, X. Contention And Ambiguity: Mining And The Possibilities Of Development. Dev. Change 2008, 39, 887–914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bastida, E. Integrating Sustainability Into Legal Frameworks for Miningin Some Selected Latin American Countries. In Mining, Minerals and Sustainable Development; Centre For Energy, Petroleum And Mineral: Dundee, UK, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Worldbank. Sector Licensing Studies: Mining Sector; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2011; Available online: http://Documents.Worldbank.Org/Curated/En/867071468155129330/Sector-Licensing-Studies-Mining-Sector (accessed on 10 November 2017).

- Cameron, P.D.; Stanley, M.C. Oil, Gas., And Mining: A Sourcebook for Understanding The Extractive Industries; World Bank Publications: Washington, DC, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Campbell, B. Revisiting The Reform Process of African Mining Regimes. Can. J. Dev. Stud. Rev. Can. D’études Dév. 2010, 30, 197–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onorato, W.; Fox, P.; Strongman, J.E. World Bank Group Assistance for Minerals Sector: Development and Reform in Member Countries; World Bank Technical Paper, No. Wtp 405; The World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- General Statistic Office. Statistic Handbook of Vietnam; General Statistic Office, Statistical Publishing House: Ha Noi, Vietnam, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen, B.N.; Boruff, B.; Tonts, M. Indicators of Mining in Development: A Q-Methodology Investigation of Two Gold Mines in Quang Nam Province, Vietnam. Res. Policy 2018, 57, 147–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, N.B.; Boruff, B.; Tonts, M. Mining, Development and Well-Being in Vietnam: A Comparative Analysis. Ext. Ind. Soc. 2017, 4, 564–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fong-Sam, Y. The Mineral Yearbook: The Mineral Industry of Viet Nam. In Survey; United States Geological, US Government: Reston, VA, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Murfitt, R. Reform of The Minerals Law: Clarity of Administrative/Permitting Procedures and Governmental Authority. In Business Issues Bulletin; Vietnam Chamber of Commerce and Industry (Vcci): Hanoi, Vietnam, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Natural Resources and Environment (MONRE); Central Economic Council (CEC); National Assembly Economic Council (NAEC). Tham Luận Hội Thảo: Đánh Giá 5 Năm Thực Hiện Chủ Trương Chính Sách Và Pháp Luật Về Khoáng Sản; Ministry of Natural Resources and Environment/The Central Economic Council/The National Assembly Economic Council: Hànoi, Vietnam, 2017.

- Bourgouin, F. The Politics Of Large-Scale Mining In Africa: Domestic Policy, Donors, And Global Economic Processes. J. S. Afr. Inst. Min. Metall. 2011, 111, 525–529. [Google Scholar]

- Worldbank. Strategy for African Mining; Technical Paper Number 181; Mining Unit, Industry and Energy Division: Washington, DC, USA, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Worldbank. Mining Strategy for Latin America and Caribbean; Worldbank Technical Paper No. 345; Worldbank: Washington, DC, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Pring, G.; Otto, J.L.; Naito, K. Trends In International Environmental Law Affecting The Minerals Industry. J. Energy Nat. Res. Law 1999, 17, 39–55. [Google Scholar]

- UN. United Nations Declaration on The Rights of Indigenous Peoples; United Nations: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2007; Available online: http://Www.Un.Org/En/Genocideprevention/Documents/Atrocity-Crimes/Doc.18_Declaration%20rights%20indigenous%20peoples.Pdf (accessed on 1 November 2017).

- Rustad, S.A.; Le Billon, P.; Lujala, P. Has The Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative Been A Success? Identifying And Evaluating Eiti Goals. Res. Policy 2017, 51, 151–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sagebien, J.; Lindsay, N. Governance Ecosystems: Csr in The Latin American Mining Sector; Palgrave Macmillan: New York, NY, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Besada, H.; Martin, P. Mining Codes in Africa: Emergence of A ‘Fourth’ Generation? Camb. Rev. Int. Aff. 2015, 28, 263–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IFC. Performance Standards on Environmental and Social Sustainability; International Finance Corporation: Washington, DC, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Miranda, M.; Chambers, D.; Coumans, C. Framework for Responsible Mining: A Guide to Evolving Standards; Center for Science in Public Participation: Bozeman, MT, USA, 2005; Available online: http://Wedocs.Unep.Org/Handle/20.500.11822/19664 (accessed on 25 October 2017).

- Goodland, R. Responsible Mining: The Key to Profitable Resource Development. Sustainability 2012, 4, 2099–2126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IESR. The Framework for Extractive Industries Governance In Asean; Institute For Essesntial Service Reform: Jakarta, Indonesia, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- IESR. Governance of Extractive Industries in Southeast Asia; Institute for Essesntial Service Reform: Jakarta, Indonesia, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Hilson, G.; Hilson, A.; Mcquilken, J. Ethical Minerals: Fairer Trade for Whom? Res. Policy 2016, 49, 232–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NRGI. Natural Resource Charter Benchmarking Framework; Natural Resource Governance Institute: New York, NY, USA, 2017; Available online: Https://Resourcegovernance.Org/Sites/Default/Files/Documents/Natural-Resource-Charter-Benchmarking-Framework-Report-2017-Web_0.Pdf (accessed on 10 July 2019).

- Ambe-Uva, T. Whither The State? Mining Codes And Mineral Resource Governance in Africa. Can. J. Afr. Stud. Revue Can. Études Afr. 2017, 51, 81–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goverment of Vietnam. Mineral Law; Goverment of Vietnam: Hanoi, Vietnam, 2011.

- Fong-Sam, Y. The Mineral Industry of Vietnam. In 2010 Minreal Yearbook: Vietnam; U.S. Geological Survey: Reston, VA, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- National Assembly. Luật Khoáng Sản. In Assembly; 60/2010/Qh12; National Assembly: Ha Noi, Vietnam, 2010; Available online: Http://Vanban.Chinhphu.Vn/Portal/Page/Portal/Chinhphu/Hethongvanban?Class_Id=1&_Page=1&Mode=Detail&Document_Id=98639 (accessed on 22 October 2017).

- Monre. Đánh Giá Tình Hình 05 Năm Thực Hiện Chủ Trương Chính Sách Và Pháp Luật Về Khoáng Sản; Ministry of Natural Resources and Environment/The Central Economic Council/The National Assembly Economic Council: Hànoi, Vietnam, 2017.

- Binh, H.T. Reform of The Minerals Law: Consistent and Fair Fiscal Regime should be Established. In Business Issues Bulletin; Vietnam Chamber of Commerce and Industry: Hanoi, Vietnam, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Tran, T.T.; Nguyen, T.L.; Nguyen, V.D. Khoáng Sản—Phát Triển—Môi Trường: Đối Chiếu Giữa Lý Thuyết Và Thực Tiễn; People and Nature Reconciliation: Hanoi, Vietnam, 2012; Available online: http://Nature.Org.Vn/Vn/2013/05/Khoang-San-Phat-Trien-Moi-Truong/ (accessed on 30 October 2017).

- Nguyen, N.; Boruff, B.; Tonts, M. Fool’s Gold: Understanding Social, Economic and Environmental Impacts from Gold Mining in Quang Nam Province, Vietnam. Sustainability 2018, 10, 1355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steven, M.; Fulton, G. Technical Report on Feasibility Studies for the Phuoc Son Gold Project in Quang Nam Province, Vietnam; Olympus Pacific Mineral Inc.: Ha Noi, Vietnam, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Stevens, M.; Fulton, G. Technical Review of Bong Mieu Gold Project in Quang Nam Province; Vietnam for Olympus: Hanoi, Vietnam, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen, D.A.; Tran, T.T.T.; Tran, T.T.H. Bộ Tiêu Chuẩn Eiti 2013 Và Khả Năng Đáp Ứng Chính Sách Của Việt Nam; Nhà Xuất Bản Hà Nội: Hanoi, Vietnam, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Prime Minister. Quy Định Chi Tiết Thi Hành Một Số Điều Của Luật Khoáng Sản. In Minister; 15/2012/Nđ-Cp; Office of The Prime Minister: Ha Noi, Vietnam, 2012; Available online: http://Vanban.Chinhphu.Vn/Portal/Page/Portal/Chinhphu/Hethongvanban?Class_Id=1&Mode=Detail&Document_Id=156031&Category_Id=0 (accessed on 24 October 2017).

- Naec. Tăng Cường Vai Trò Giám Sát Của Quốc Hội Trong Việc Thực Hiện Chính Sách, Pháp Luật Về Khoáng Sản. Đánh Giá 5 Năm Thực Hiện Chủ Trương, Chính Sách Và Pháp Luật Về Khoáng Sản; Monre, National Assembly Economic Committee: Hanoi, Vietnam, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Vusta. Thực Trạng Về Quản Lý Khai Thác Và Sử Dụng Tài Nguyên Khoáng Sản Việt Nam; Vietnam Science and Technology Association: Hanoi, Vietnam, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Monre. Báo Cáo Hoạt Động Khoáng Sản; A Report of Mineral Activities; Ministry of Natural Resources and Environment: Moscow, Russia, 2015.

- Vo, H.D. Thực Trạng Công Tác Quản Lý Khai Thác Tài Nguyên Thiên Nhiên Ở Nước Ta Và Nhu Cầu Tăng Cường Tính Minh Bạch. 2014. Available online: http://nature.org.vn/vn/wp-content/uploads/2014/07/Prof.-Dang-Hung-Vo.pdf (accessed on 3 October 2017).

- Dau, A.; Phan, M.T.; Nguyễn, M.D.; Đinh, T. Báo Cáo Về Mức Độ Tuân Thủ Các Quy Định Pháp Luật Về Minh Bạch Trong Lĩnh Vực Khoáng Sản; Vietnam Chamber of Commerce and Industry and Vietnam Mining Coalition: Ha Noi, Vietnam, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Tran, V.T. Vietnamese Economy at The Crossroads: New Doi Moi For Sustained Growth. Asian Econ. Policy Rev. 2013, 8, 122–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Worldbank. Natural Resource Management; Vietnam Development Report 2011; The Worldbank: Hanoi, Vietnam, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Monre. Tổng Kết 13 Năm Thi Hành Luật Khoáng Sản (1996–2009) (A Report Of Thirteen Year to Implement The Mineral Law (1996–2009); Ministry of Natural Resources and Environment: Ha Noi, Vietnam, 2010.

- Tran, B. Dễ Dãi Cấp Phép Khai Thác Khoáng Sản. Người Lao Động. 2013. Available online: http://nld.com.vn/thoi-su-trong-nuoc/de-dai-cap-phep-khai-thac-khoang-san-20130826100042488.htm (accessed on 30 October 2017).

- Dau, A.T.; Nguyen, M.D.; Tran, T.T.; Trinh, L.N.; Duong, V.T.; Le, X.T. Thực Thi Eiti: Để Cải Cách Ngành Công Nghiệp Khai Thác Khoáng Sản Ở Việt Nam; Vietnam Chamber of Commerce and Industry, Vietnam Mining Coalition and Pannature: Ha Noi, Vietnam, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- VCCI. Thực Trạng Hoạt Động Của Doanh Nghiệp Khai Khoáng Tại Việt Nam; Vietnam Chamber of Commerce And Industry: Hanoi, Vietnam, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Rgi. The 2013 Resource Governance Index: Vietnam; Natural Resouce Governance Institute: Hanoi, Vietnam, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Sang, H.; Huy, Q. Tôi Đi ‘Chạy’ Giấy Phép Khai Thác Mỏ. Vietnamnet. 2011. Available online: http://vietnamnet.vn/vn/xa-hoi/toi-di--chay--giay-phep-khai-thac-mo-21192.html (accessed on 24 October 2017).

- Tuyen, P. Lĩnh Vực Khoáng Sản: Khâu Nào Cũng Có Thể Tham Nhũng. Tienphong. 2011. Available online: http://www.tienphong.vn/Print.aspx?id=539362 (accessed on 30 October 2017).

- Dougherty, M.L. The Global Gold Mining Industry: Materiality, Rent-Seeking, Junior Firms and Canadian Corporate Citizenship. Compet. Chang. 2013, 17, 339–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.J.P.; Li, Z.; Su, X.; Sun, Z. Rent-Seeking Incentives, Corporate Political Connections, and The Control Structure of Private Firms: Chinese Evidence. J. Corp. Finan. 2011, 17, 229–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vu, M.H. Kết Quả 5 Năm Thực Hiện Nghị Quyêt Số 02-Nq/Tư Của Bộ Chính Trị. Đánh Giá 5 Năm Thực Hiện Chủ Trường Chính Sách Và Pháp Luật Về Khoáng Sản; Ministry Of Natural Resource And Environment: Hànoi, Vietnam, 2017.

- Le, D.D. Ngành Công Nghiệp Khai Thác Khoáng Sản Ở Việt Nam Còn Nhiều Bất Cập. In Bản Tin Chính Sách: Tài Nguyên-Môi Trường-Phát Triển Bền Vững; Pannature: Hanoi, Vietnam, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Nam, C.N.; Bich, T.D. Thuế Phí Khoáng Sản Hiện Đang Quá Cao; Vietnam National Coal Mineral Industries Holding Corporation Limited: Hanoi, Vietnam, 2016; Available online: http://Www.Vinacomin.Vn/Tap-Chi-Than-Khoang-San/Thue-Phi-Khoang-San-Hien-Dang-Qua-Cao-201608031132109479.Htm (accessed on 18 January 2017).

- Government. Quy Định Về Phương Pháp Tính, Mức Thu Tiền Cấp Quyền Khai Thác Khoáng Sản. 203/2013/Nđ-Cp. 2014. Available online: http://Vanban.Chinhphu.Vn/Portal/Page/Portal/Chinhphu/Hethongvanban?Class_Id=1&Mode=Detail&Document_Id=171117 The Vietnamese Government (accessed on 9 October 2017).

- Monre. Quy Định Chi Tiết Một Số Điều Của Nghị Định Số 22/2012/Nđ-Cp Ngày 26 Tháng 3 Năm 2012 Của Chính Phủ Quy Định Về Đấu Giá Quyền Khai Thác Khoáng Sản. 201254/2014/Ttlt-Btnmt-Btc. 2012. Available online: http://vanban.chinhphu.vn/portal/page/portal/chinhphu/hethongvanban?class_id=1&_page=1&mode=detail&document_id=176161 (accessed on 21 October 2017).

- National Assembly. Luật Bảo Vệ Môi Trường in Assembly. 5/2014/Qh13. 2015. Available online: Http://Vanban.Chinhphu.Vn/Portal/Page/Portal/Chinhphu/Hethongvanban?Class_Id=1&_Page=1&Mode=Detail&Document_Id=175357 (accessed on 23 October 2017).

- Government. Quyết Định: Về Cải Tạo, Phục Hồi Môi Trường Và Ký Quỹ Cải Tạo, Phục Hồi Môi Trường Đối Với Hoạt Động Khai Thác Khoáng Sản 18/2013/Qđ-Ttg. 2013. Available online: http://Congbao.Chinhphu.Vn/Noi-Dung-Van-Ban-So-18-2013-Qd-Ttg-4013 (accessed on 9 October 2017).

- Monre. Thông Tư: Về Cải Tạo, Phục Hồi Môi Trường Trong Hoạt Động Khai Thác Khoáng Sản. 38/2015/Tt-Btnmt. 2015. Available online: http://Congbao.Chinhphu.Vn/Noi-Dung-Van-Ban-So-38-2015-Tt-Btnmt-15380 (accessed on 21 October 2017).

- Manh, M. Hà Giang: Tổn Thất Tài Nguyên Rừng, Ô Nhiễm Tăng Vì Khai Thác Mỏ. Vietnam Plus. 2015. Available online: http://www.vietnamplus.vn/ha-giang-ton-that-tai-nguyen-rung-o-nhiem-tang-vi-khai-thac-mo/346735.vnp (accessed on 25 October 2017).

- Monre. Báo Cáo Môi Trường Quốc Gia 2011 Về Chất Thải Rắn; Ministry of Natural Resource and Environment: Hanoi, Vietnam, 2011. Available online: http://Vanban.Chinhphu.Vn/Portal/Page/Portal/Chinhphu/Hethongvanban?Class_Id=1&_Page=1&Mode=Detail&Document_Id=176161 (accessed on 21 October 2017).

- Government. Nghị Định: Quy Định Tổ Chức, Bộ Phận Chuyên Môn Về Bảo Vệ Môi Trường Tại Cơ Quan Nhà Nước Và Doanh Nghiệp Nhà Nước. 81/2007/Nđ-Cp. 2007. Available online: https://thuvienphapluat.vn/van-ban/Bo-may-hanh-chinh/Nghi-dinh-81-2007-ND-CP-to-chuc-bo-phan-chuyen-mon-bao-ve-moi-truong-tai-co-quan-doanh-nghiep-nha-nuoc-20494.aspx (accessed on 3 October 2017).

- Government. Nghị Định: Quy Định Tổ Chức Các Cơ Quan Chuyên Môn Thuộc Ủy Ban Nhân Dân Tỉnh, Thành Phố Trực Thuộc Trung Ương in 13/2008/NĐ-CP. 2008. Available online: thuvienphapluat.vn: https://thuvienphapluat.vn/van-ban/Bo-may-hanh-chinh/Nghi-dinh-13-2008-ND-CP-to-chuc-co-quan-chuyen-mon-thuoc-Uy-ban-nhan-dan-tinh-thanh-pho-truc-thuoc-Trung-uong-62259.aspx (accessed on 5 October 2017).

- Government. Quyết Định: Về Ký Quỹ Cải Tạo, Phục Hồi Môi Trường Đối Với Hoạt Động Khai Thác Khoáng Sản in 71/2008/QĐ-TTg. thuvienphapluat.vn; 2008. Available online: https://thuvienphapluat.vn/van-ban/Tai-nguyen-Moi-truong/Quyet-dinh-71-2008-QD-TTG-ky-quy-cai-tao-phuc-hoi-moi-truong-doi-voi-hoat-dong-khai-thac-khoang-san-66456.aspx (accessed on 6 October 2017).

- Government. Nghị Định: Về Phí Bảo Vệ Môi Trường Đối Với Khai Thác Khoáng Sản in 63/2008/NĐ-CP. thuvienphapluat.vn; 2008. Available online: https://thuvienphapluat.vn/van-ban/Thue-Phi-Le-Phi/Nghi-dinh-63-2008-ND-CP-phi-bao-ve-moi-truong-doi-voi-khai-thac-khoang-san-65781.aspx (accessed on 10 October 2017).

- Government. Nghị Định: Về Phí Bảo Vệ Môi Trường Đối Với Khai Thác Khoáng Sản in 74/2011/NĐ-CP. thuvienphapluat.vn; 2011. Available online: https://thuvienphapluat.vn/van-ban/Thue-Phi-Le-Phi/Nghi-dinh-74-2011-ND-CP-phi-bao-ve-moi-truong-khai-thac-khoang-san-128376.aspx (accessed on 6 October 2017).

- Vusta. Xung Quanh Việc Triển Khai Các Dự Án Khai Thác Bauxit Ở Tây Nguyên—Những Kiến Nghị Khoa Học; Vietnam Union Of Science And Technology Association: Hanoi, Vietnam, 2009; Available online: http://www.vusta.vn/vi/news/Trao-doi-Thao-luan/Xung-quanh-viec-trien-khai-cac-du-an-khai-thac-bauxit-o-Tay-Nguyen-Nhung-kien-nghi-khoa-hoc-29832.html (accessed on 3 November 2017).

- Lan, H. ‘Làng Nhiễm Chì’ Dưới Chân Núi Phja Khao. Saigon Online. 2007. Available online: http://www.sggp.org.vn/SGGP12h/2007/6/103138/# (accessed on 16 October 2017).

- Besra. Besra Welcomes Improvements To Vietnam Gold Royalty Law. 2015. Available online: http://Www.Besra.Com/Besra-Welcomes-Improvements-To-Vietnam-Gold-Royalty-Law/ (accessed on 25 September 2017).

- Government. Nghị Quyết: Về Việc Ban Hành Chương Trình Hành Động Của Chính Phủ Thực Hiện Nghị Quyết Số 02/Nq Tw Ngày 25 Tháng 4 Năm 2011 Của Bộ Chính Trị Về Định Hướng Chiến Lược Khoáng Sản Và Công Nghiệp Khai Khoáng Đến Năm 2020, Tầm Nhìn Đến Năm 2030. 103/Nq Cp. 2011. Available online: http://congbao.chinhphu.vn/noi-dung-van-ban-so-103-nq-cp-4814 (accessed on 8 October 2017).

- Government. Quyết Định: Phê Duyệt Chiến Lược Khoáng Sản Đến Năm 2020, Tầm Nhìn Đến Năm 203. 2427/Qđ Ttg. 2011. Available online: http://Congbao.Chinhphu.Vn/Noi-Dung-Van-Ban-So-2427-Qd-Ttg-794 (accessed on 8 October 2017).

- National Assembly. Nghị Quyết: Về Việc Ban Hành Biểu Mức Thuế Suất Thuế Tài Nguyên. 928/2010/Ubtvqh12. 2010. Available online: https://Thuvienphapluat.Vn/Van-Ban/Thue-Phi-Le-Phi/Nghi-Quyet-928-2010-Ubtvqh12-Bieu-Muc-Thue-Suat-Thue-Tai-Nguyen-105808.Aspx (accessed on 22 October 2017).

- Besra. Besra Completes Divestment of Vietnam Subsidiaries. 2017. Available online: http://Www.Besra.Com/Vn-Sale-Complete/ (accessed on 26 September 2017).

- Ilo. C169—Indigenous and Tribal Peoples Convention (No. 169). International Labour Organisation, 1989. Available online: http://Www.Ilo.Org/Dyn/Normlex/En/F?P=Normlexpub:12100:0::No::P12100_Ilo_Code:C169 (accessed on 20 October 2017).

- Moti. Tình Hình 5 Năm Thực Hiện Nghị Quyết 02-Nq/Tư Ngày 25/04/2011 Của Bộ Chính Trị Và Các Tác Động Của Luật Khoáng Sản Năm 2010. Đánh Giá 5 Năm Thực Hiện Chủ Trương Chính Sách, Pháp Luật Về Khoáng Sản; Monre: Hanoi, Vietnam, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Ti. Corruption Perceptions Index; Transparency International: Berlin, Germany, 2017; Available online: https://Www.Transparency.Org/News/Feature/Corruption_Perceptions_Index_2017 (accessed on 25 October 2017).

- Malesky, E.; Phan, T.N.; Pham, N.T. The Vietnam Provincial Competitiveness Index: Measuring Economic Governance For Private Sector Development, 2017; Final Report; Vietnam Chamber of Commerce and Industry and United States Agency for International Development: Hanoi, Vietnam, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Pannature & Oxfam. Quản Trị Bền Vững Ngành Khai Thác Khoáng Sản Tại Việt Nam Thông Qua Thực Hiện Sáng Kiến Minh Bạch Công Nghiệp Khai Thác (Eiti); Đánh Giá 5 Năm Thực Hiện Chủ Trương Chính Sách Và Pháp Luật Về Khoáng Sản/Monre: Hanoi, Vietnam, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Gso. Sự Phát Triển Của Doanh Nghiệp Việt Nam Giai Đoạn 2010–2014; General Statistics Office: Hanoi, Vietnam, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Vu, T.T.A.; Chirot, L.; Dapice, D.; Huynh, T.D.; Pham, D.N.; Perkins, D.; Nguyen, X.T. Institutional Reform: From Vision To Reality. In Vietnam Executive Leadership Program (Velp); Harvard Kennedy School: Cabridge, MA, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Vinacomin. Báo Cáo Tài Chính Kiểm Toán Cho Năm Tài Chính Kết Thúc Vào 31/12/2016; Vietnam National Coal-Mineral Industry Holding Corporation Limited: Hanoi, Vietnam, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Besra. Besra Resumes Operations At The Phuoc Son Mine In Vietnam After A Temporary Shutdown. 2013. Available online: http://Www.Besra.Com/Besra-Production-Resumes-At-Phuoc-Son/ (accessed on 28 October 2017).

- Goverment Of Vietnam. Thông Báo 207/Tb-Vpcp: Kêt Luận Của Phó Thủ Tướng Trương Hòa Bình Tại Buổi Làm Việc Với Lãnh Đạo Tỉnh Quảng Nam. 2016. Available online: http://Vanban.Chinhphu.Vn/Portal/Page/Portal/Chinhphu/Hethongvanban?Class_Id=2&_Page=1&Mode=Detail&Document_Id=185793: Văn Phòng Chính Phủ (accessed on 2 October 2017).

- Besra. Besra Suspends Operations In Vietnam. 2014. Available online: http://Www.Besra.Com/Besra-Suspends-Operations-Vietnam/ (accessed on 27 October 2017).

- Chung, Q. Tài Nguyên Khoáng Sản Và … Thuế. Thoi Bao Kinh Te Sai Gon. 2009. Available online: http://duthaoonline.quochoi.vn/DuThao/Lists/TT_TINLAPPHAP/View_Detail.aspx?ItemID=286 (accessed on 28 September 2017).

- Lan, N. Bộ Tài Chính Lấy Ý Kiến Về Đề Nghị Nâng Thuế Tài Nguyên. Kinh Te Sai Gon. 2015. Available online: https://www.thesaigontimes.vn/130765/bo-tai-chinh-lay-y-kien-ve-de-nghi-nang-thue-tai-nguyen.html/ (accessed on 30 October 2017).

- Huyen, K. Chính Sách Tài Chính: Bảo Vệ, Khai Thác, Sử Dụng Hiệu Quả Nguồn Tài Nguyên Khoáng Sản. Thoi Bao Tai Chinh. 2017. Available online: http://thoibaotaichinhvietnam.vn/pages/thoi-su/2017-04-26/chinh-sach-tai-chinh-bao-ve-khai-thac-su-dung-hieu-qua-nguon-tai-nguyen-khoang-san-42771.aspx (accessed on 15 October2017).

- Devi, B.; Prayogo, D. Mining and Development in Indonesia an Overview of The Regulatory Framework and Policies; Sustainable Minerals Institute, The University of Queensland: Indooroopilly QLD, Australia, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- ASEAN. Sustainable Mineral Development: Best Practices in Asean; The Association of Southeast Asian Nations: Jakarta, Indonesia, 2017. [Google Scholar]

| Element | Component |

|---|---|

| Legal frameworks |

|

| Economic and fiscal policies |

|

| Institutional reforms |

|

| Corporate Social Responsibility(CSR) and participation of affected peoples |

|

| Access to mining activities |

|

| Ongoing obligations |

|

| Regulatory aspects |

|

| Ancillary licenses and permits |

|

| Investment contracts |

|

| Environmental and Social matters |

|

| Government Agencies | Responsibilities |

|---|---|

| Ministry of Natural Resources and Environment (MONRE) |

|

| Ministry of Commerce (MOCOM) |

|

| Ministry of Construction (MOCON) |

|

| Ministry of Planning and Investment (MPI) |

|

| Ministry of Finance (MOF) |

|

| Provincial People’s Committee (PPC) |

|

| Commune and District People’s Committee (CPC and DPC) |

|

| Phuoc Duc | Phuoc Nang | Tam Lanh | Tam An | District | Province | Total | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mining | Non-Mining | Mining | Non-Mining | |||||||||||

| Male (M) | Female (F) | M | F | M | F | M | F | M | F | M | F | M | F | |

| Local residents 1 | 10 | 19 | 21 | 39 | 37 | 14 | 30 | 26 | 98 | 98 | ||||

| Miners | 14 | 1 | 4 | 19 | 0 | |||||||||

| Mining management | 1 | 3 | 1 | 4 | 1 | |||||||||

| NGO (World Vision) | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||||||||

| Gov. authorities 2 | 4 | 6 | 10 | 9 | 4 | 5 | 9 | 3 | 17 | 4 | 13 | 1 | 57 | 28 |

| Total | 30 | 26 | 32 | 48 | 45 | 19 | 39 | 29 | 17 | 4 | 16 | 2 | 179 | 128 |

| MMc Element | MMc Indicator | Achievements and Deficiencies |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Legal frameworks | 1.1. Clarity, constancy, minimal discretion and coordination | - Overly complicated |

| - Difficult to understand | ||

| - Policy inconsistencies | ||

| 1.2. Applying equally to all investors | - Priorities and privileges to SOEs and related-SOEs | |

| 1.3. Long-term security of tenure | ✓ | |

| 1.4. Guarantee of commitments in exchange | ✓ | |

| 2. Economic and fiscal policies | 2.1. Promote good macroeconomic policy and governance | - Inconsistent mining regulations |

| - Illogical economic policies | ||

| - Prevalence of corruption | ||

| - Ineffective management | ||

| 2.2. Foreign exchange access | ✓ | |

| 2.3. Focusing on earning-based taxes and decrease operating losses | - Does not identify natural resource tax for a specific mineral | |

| - High taxes | ||

| - Tax calculated by volume and quality of ores | ||

| 3. Institutional reforms and infrastructure | 3.1. Responsibility of Government for privatisation of SOEs | ✓ |

| 3.2. Elimination of political pressure | - “Master plans” created by the Government | |

| - Privileges to SOEs | ||

| - Numerous Governmental agencies involved with management | ||

| - Bureaucracy | ||

| - Lack of transparency | ||

| - Breaches of licensing process | ||

| - Corruption and rent-seeking behaviour | ||

| 3.3. Health and safety regulations | ✓ | |

| 3.4. Good infrastructure to address environmental issues | - Further provisions and clarification required | |

| 3.5. Regulate artisanal mining | - Not identified | |

| 4. CSR and participation of affected peoples | 4.1. Development and empowerment | - Further provisions and clarification required |

| 4.2. Adopting CSR codes | - Not identified | |

| 4.3. Arbitration of impacts on local peoples | - Unclear and need further clarification | |

| 4.4. Free, prior, informed consent | - Not identified | |

| 4.5. Address indigenous issues | - Unclear and unsubstantiated concerns | |

| - Further provisions needed | ||

| 4.6. Address resettlement issue | ✓ | |

| 5. Access to mining activities | 5.1. Mining rights | ✓ |

| 5.2. Conversion rights | ✓ | |

| 5.3. Prospecting rights | ✓ | |

| 6. Ongoing obligations | 6.1. Compliance by mining company | - Increased specificity required |

| - Ineffective law enforcement | ||

| 6.2. Provide Force Majeure | - Not identified | |

| - Clarification of environmental regulations required | ||

| 7. Regulatory aspects | 7.1. Stipulate rights of regulatory authority | ✓ |

| 7.2. Provide sufficient powers to regulatory bodies | ✓ | |

| 8. Supporting licenses | 8.1. Identify rights of resource use | ✓ |

| 9. Investment contracts | 9.1. Provide opportunities to modify or supersede | ✓ |

| 10. Environmental and social matters | 10.1. Assessing and monitoring mining projects | - Inconsistent management of mining tailings |

| - Lack of responsibility of relevant agencies | ||

| - Noncompliance by mining companies | ||

| - Reclamation and rehabilitation requirements not met | ||

| - Inadequate protection of local people’s property rights. | ||

| 10.2. Incorporating safeguard measures for environment, health and safety | - Inadequate (low) environmental fee | |

| - Ineffective collaboration among agencies | ||

| - Ineffective monitoring of transfer tax revenues | ||

| - Vulnerabilities to health and livelihoods | ||

| 10.3. Compliance incentives and tax deductions | - Not identified | |

| - Low recruitment of local peoples | ||

| - Ineffective CSR initiatives |

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ba Nguyen, N.; Boruff, B.; Tonts, M. The Regulatory Framework and Minerals Development in Vietnam: An Assessment of Challenges and Reform. Sustainability 2019, 11, 4861. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11184861

Ba Nguyen N, Boruff B, Tonts M. The Regulatory Framework and Minerals Development in Vietnam: An Assessment of Challenges and Reform. Sustainability. 2019; 11(18):4861. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11184861

Chicago/Turabian StyleBa Nguyen, Nhi, Bryan Boruff, and Matthew Tonts. 2019. "The Regulatory Framework and Minerals Development in Vietnam: An Assessment of Challenges and Reform" Sustainability 11, no. 18: 4861. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11184861

APA StyleBa Nguyen, N., Boruff, B., & Tonts, M. (2019). The Regulatory Framework and Minerals Development in Vietnam: An Assessment of Challenges and Reform. Sustainability, 11(18), 4861. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11184861