1. Introduction

There has been a lively debate among urban scholars and practitioners about the potential and mechanisms of ‘urban transformation’. However, there is still limited agreement on what exactly sustainable urban transformation looks like in practice and how (and even whether) it can be achieved. While there is widespread agreement among urban scholars that ‘radical’ transformations are needed, cities are complex systems and urbanization is not a linear and simple process. Given the fast pace of urban expansion [

1,

2], how to spark and sustain sustainable urban transformations is one the most important development questions of our time. Answering it is essential for achieving the change needed for safe, inclusive, resilient and sustainable cities [

2,

3,

4].

However, this question is remarkably difficult to answer. Real world examples of deep urban transformations are hard to come by. Study after study finds little evidence of radical changes happening in cities [

3,

5]. In fact, scarce empirical evidence in the academic literature leads some scholars to diagnose an “implementation gap” between theoretical concepts and claims about the nature of sustainable urban transformation. While far-reaching, radical, cross and multi-sectoral transformations are needed, the evidence of the practical performance of projects and initiatives is at best partial, sector-based and incremental [

4,

5]. Therefore, there is a need to surface good examples of urban transformation that can help build a knowledge base that responds to the complexity of urban challenges and sparks a pragmatic movement around progressive urban agendas that practitioners can use to transform their cities [

6].

This paper is set in the context of an ‘emergent epistemic community’ on urban transformation that is attempting to do exactly that. An interdisciplinary field with open boundaries, at the intersection of complex systems studies and urban studies [

7], it has been forming around a normative framing of urban transformations to sustainability [

6]. There are several things to note about this, according to two recent systematic literature reviews [

6,

7]. For one, the term itself (‘urban transformation’) has been used heterogeneously for the last six decades. It has mostly been applied outside of the ‘sustainability’ debate, to issues as diverse as rural–urban migration, post-socialist transformation, and changes in the built environment or in urban cultures [

6]. The approaches that do focus on the need for “sustainable” urban transformation are a small—albeit growing—subset of the larger body of research. Second, there is internal diversity within this subset, with publications covering a variety of sustainability goals, including low-carbon cities and adaptation, efficiency and innovations in urban infrastructures and services, and systems of consumption. Third, despite internal diversity, there is concentration in terms of a focus on higher income cities (in particular, Western Europe) and megacities, which are published within a relatively small radius of academic publications [

5,

8], and a larger sphere of grey (often not peer-reviewed) publications.

Our contribution to this emerging community of practitioners is aligned with a recent call for strategic extensions and alternative research methods to complement and push the horizon of the existing empirical knowledge base and methodological repertoire [

8,

9]. It is also responsive to cautions surrounding the ‘elasticity’ in how the concept of ‘transformation’ is used, having entered policy and practice without consensus and empirical grounding, and little guidance for implementation in all three spheres of practice, research and funding [

10,

11,

12]. Our research is informed by an initiative at the World Resources Institute, namely, the WRI Ross Prize for Cities (hereafter, ‘the prize’), a global award for transformative projects that have ignited sustainable changes in their city. Between February 2018 and April 2019, we carried out an evaluation of almost 200 submissions to the first edition of the prize. We developed and implemented a process to source, evaluate and help select one winning submission from a diverse pool of sectors, countries, organizations, types of activities, project sizes, types of transformation and impacts.

In this context, we found it useful to contrast transformation with another concept, namely that of ‘transition’. The relationship between these two concepts has received attention in the academic literature, with a focus on whether there is a qualitative distinction between ‘transformation’ versus ‘transition’ [

9,

13]. While sometimes used interchangeably [

7], our experience validates the etymological distinction that links transition to a meaning of ‘going across’, while transformation relates to a ‘change in form’ [

13], indicating a relative and contextual shift that is knowable as the difference between two points in time.

In

Section 2 of this paper we explain the competition-based approach that was used to source and evaluate transformative projects and initiatives and describe in detail the evaluative framework and process. We argue that this approach helped select high impact examples of urban transformation—a significant achievement, given the aforementioned dearth of real-world examples of deep urban transformations.

Section 3 introduces the five finalists. Basing our analysis on the five high impact initiatives, in

Section 4 we reflect on a basic, yet still underexplored, question at the core of the normative urban transformation agenda: what does urban transformation look like in practice? In

Section 5 we draw conclusions relating to implications arising from the research.

2. Description of the Competition-Based Methodology

In recent years there has been a rise in the number of competitions, challenges and other prize-based approaches to source new ideas and solutions to public problems [

14]. This trend cuts across sectors—public, private, and philanthropic—and topic areas, health and international development [

15], smart cities [

16], urban innovation [

17], and local sustainability awards [

18]. Within this broader context, the WRI Ross Prize for Cities [

19] is the largest global award celebrating and spotlighting transformative projects that have ignited sustainable changes in their city. Set within the organizational context of WRI (a global research organization and ‘do tank’), it is an explicit objective of the prize to surface real world instances of deep urban transformation, and to learn from them about what makes initiatives successful, ultimately to help catalyze and inspire other transformative initiatives.

The use of evaluative approaches as a way of establishing the strength of a phenomenon is a generally well-established practice, however it has not been systematically used to understand ‘urban transformation’. We propose to take an evaluative framework, such as ours, as a ‘strategic extension’ to the existing repertoire of research designs and methods [

7]. The methodology was designed to source and evaluate submissions in terms of the extent to which they were “transformative projects igniting citywide change” (the adopted tagline of the prize). A key requirement was to have a methodology that would attract high-quality submissions and that would help us compare between entries from different sectors, countries, organizations, types of activities, project sizes, transformation and impacts. The competition-based approach had the following phases, set out in

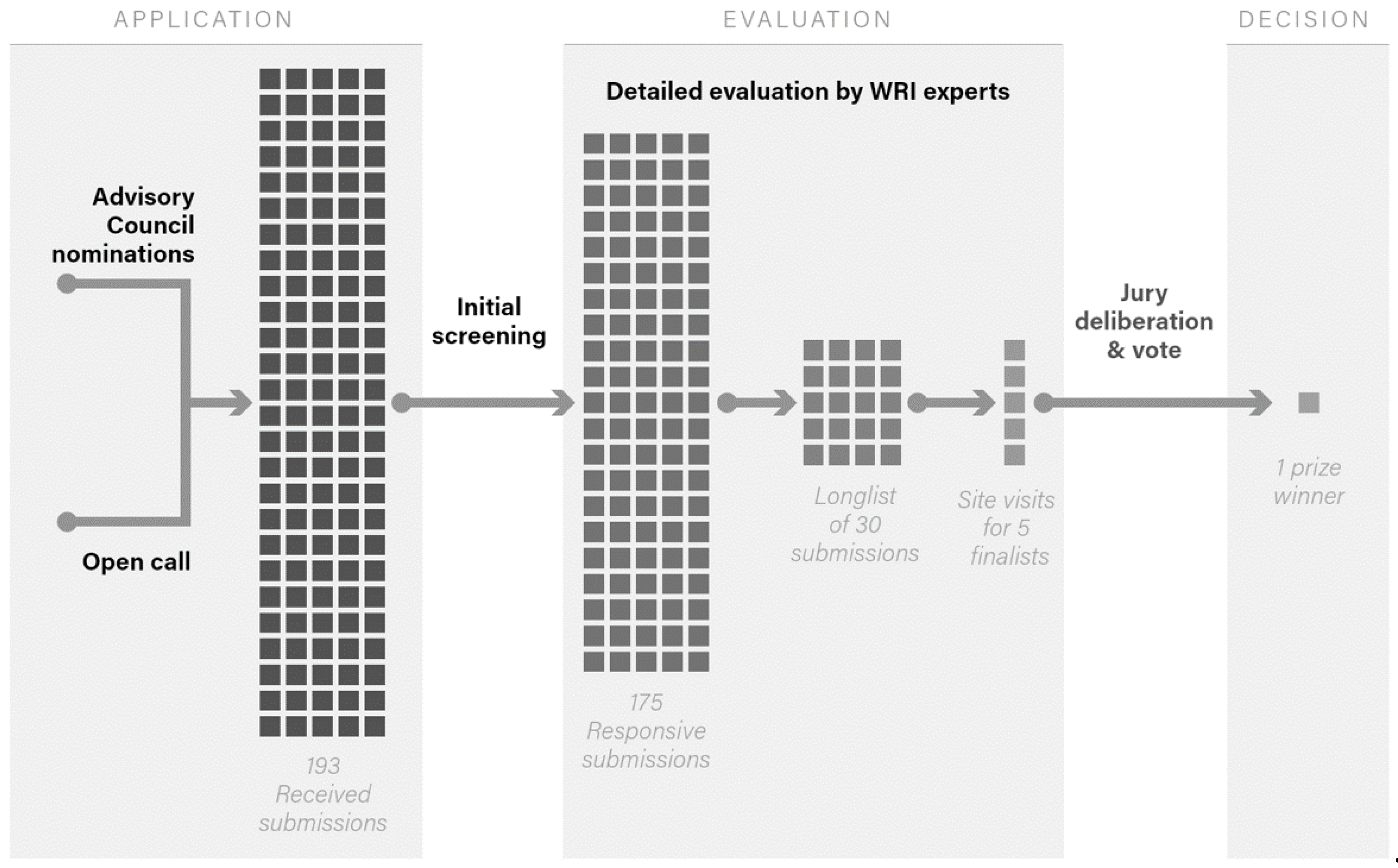

Figure 1: Preparation, Submissions, Evaluation, and Selection.

During the Preparation phase, an evaluation approach was developed, which was subsequently used to assess submissions to the prize. Through consulting the prevailing literature in transformation and urban studies, and adapting existing insights to the specific requirements of the prize, a six-criteria, five-point evaluation scale was constructed. This covered the following three dimensions of transformation, as relevant to the prize (for a full evaluation matrix, see

Appendix A):

Reach of impact: Given a focus on ‘city-wide’ transformation, it was important for us to assess whether the intervention had substantially changed the project site and surrounding areas, and that it could be demonstrated that positive impacts were sustained over time and could increase further still.

Balance of impact: Given a focus on ‘sustainable’ urban transformation, we were interested in identifying initiatives that had had positive impacts in three categories—social, environmental, and economic—and whether these were large relative to the size of the projects and their resources.

Catalytic nature: Given our focus on initiatives that ‘ignited’ deep transformations, we were concerned with identifying initiatives that deliberately targeted an important problem the city faced and contributed to tackling this problem, and whether the intervention was reproduced elsewhere.

In the Submission phase, entries were solicited from two sources: through an open call advertised through the World Resources Institute’s and partners’ various communication channels, as well as from a purposefully recruited Advisory Council, a network of more than 50 thought leaders in urban affairs. Over 90 recommendations were submitted by the Advisory Council, from over 30 countries. The importance of the Advisory Council is clear when considering that four of the five finalists were advisor-recommended (including the cash prize winner), and over one-third of recommendations ended up applying (a relatively high conversion rate). By the submission deadline, 193 submissions from 120 cities in 41 countries, across six continents were recorded in the system.

The Evaluation phase consisted of a successive narrowing of the pool of submissions, culminating in site visits to the five finalist sites. Of 193 submissions, 175 passed the initial screening, meaning that they met the formal eligibility criteria according to the Terms and Conditions and had submitted complete information through the application form. In the first round of the evaluation, a 13-person evaluation team rated 175 submissions, and based on this, a longlist of 30 submissions was produced (narrowed down from 175). In the second round, this was narrowed down to only five finalists. The creation of the long and short lists used a combination of the following decision-making rules:

“Minimum threshold”: a defined set of criteria that every submission needs to meet (e.g., minimum average rating of 3, lowest rating in any single criteria not below 2).

“Best in class”: top submissions in each category of geography and project type.

“Evaluators choice”: if a particular submission was not picked up through the former two rules, then there was room for discussion within the evaluation team to include the submission if it was deemed worthy by the majority (this affected two submissions in the pool, neither of which eventually became a finalist).

The eventual selection for the longlist was discussed and endorsed by a majority vote from the evaluation team, while the finalist shortlist concluded after additional research and due diligence had been carried out. This involved site visits to each finalist location. Site visits had the principal objective of completing and validating the understanding of the urban transformation case, and involved a tour of the project site(s), an extended meeting with the project team, and interviews with beneficiaries and key stakeholders. For additional due diligence, the team consulted a range of additional sources, as available, including official reports and evaluations, anecdotes, testimonials, press releases, and media and social coverage.

The Decision phase consisted of the selection of one finalist to receive the cash prize through a deliberative process by an external jury of 11 high-profile leaders in urban affairs, including architects, financiers, developers, business leaders, and philanthropists. The jury was briefed through a document containing a write up of each finalist and notes from the site visits. Ahead of the jury meeting, jury members submitted an initial ranking. Another vote took place on the day, following a three-hour deliberation, revealing the recipient of the cash prize. The voting method was the Borda count, a simple method in which voters rank candidates according to their preferences, and the least favorite receives one point, the second least favorite two points, and so on until the top candidates receives the topmost points (five, in this case). The candidate with the most points wins. The Borda count was seen as preferable to alternatives, such as Instant-runoff voting or the Combs method, as it does not exclusively focus on voters’ top (or bottom) choices, but takes into account the entire ordering. It was also appropriate, given the jury’s high degree of knowledge of all five candidates.

It is important to note that the winner selection was not an ‘evaluative’ process in which shared criteria were applied and does not indicate that the cash prize recipient was necessarily a ‘better’ or more impactful initiative than the other finalists. Rather, jury members were asked to determine ‘prizeworthiness’ based on which of the finalists should be elevated before a global audience through receiving the cash prize. Importantly, the jury deliberation offered an opportunity to surface opinions and views about urban transformation from leading thinkers and practitioners in the field.

Finally, it is important to note several limitations and challenges. Methodologically, this is uncharted territory. Developing markers of transformation, impact and attribution, and managing comparability (across sectors, countries, organizations, activities, and time frames) were key aspects of this methodological challenge. We were able to draw on the emerging scholarship on urban transformation and to learn from operational aspects from peer-prize initiatives. However, there are no accepted methodologies for evaluating urban transformation or transformative initiatives. In fact, in the literature, there is a lack of agreement on some of the basic terminology and concepts of urban transformation, and there are only limited efforts to relate these to practical real-world instances (e.g., [

12]). In addition, information availability and verifying the accuracy of the information provided was also a factor. Submissions to the prize were self-reported, sometimes incomplete, and additional information was not always readily available. Initiatives applied with their statement of impact and the WRI’s evaluators assessed to what extent this impact qualified as urban transformation, as defined in the evaluation matrix. For a smaller subset of submissions (finalists and top-ranking contenders), self-reported impacts were verified during deep desktop and site visit research.

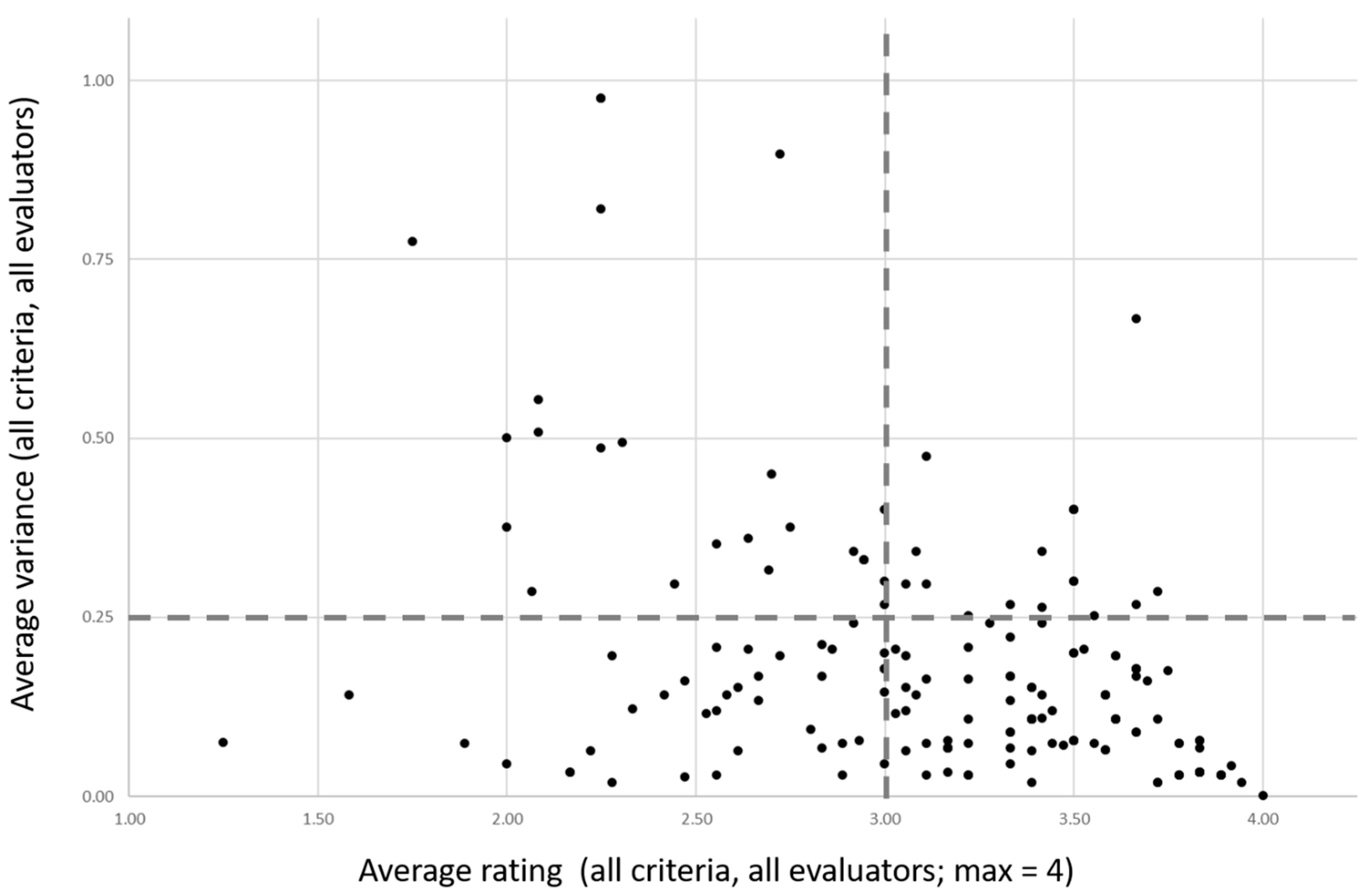

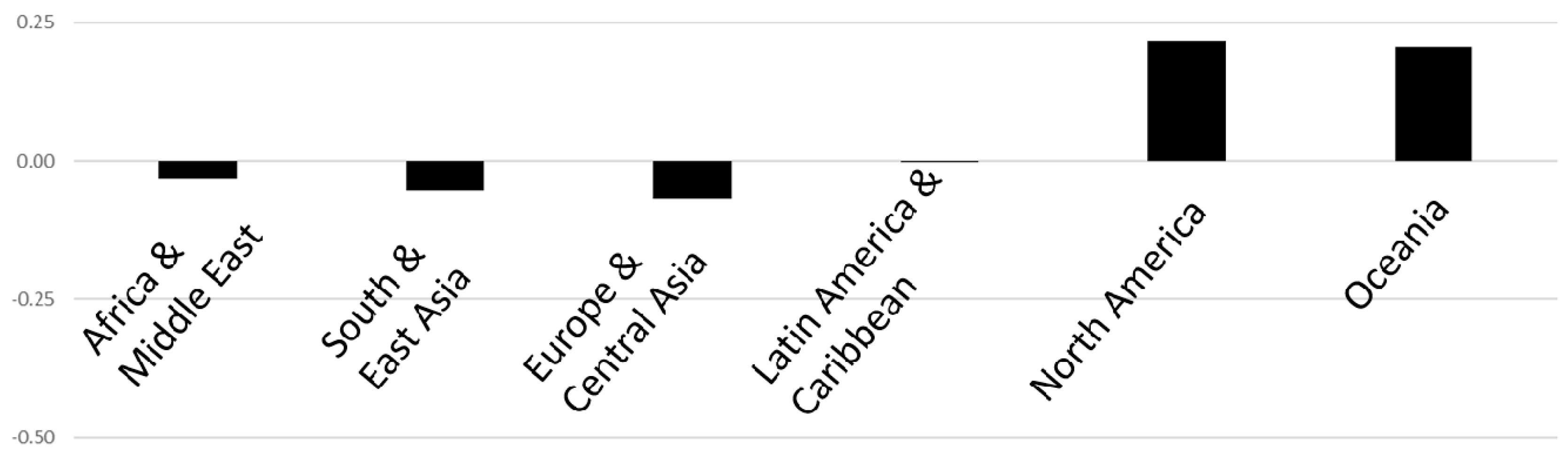

We, the authors, were involved in a leadership and support function in the evaluation process, which means we developed the evaluation methodology and led the team through the process; however, we did not take part in rating submissions or subsequently deciding the winner. In addition, we developed several measures for bias control across the evaluation team and for dealing with inconsistencies between ratings. On the one hand, we recruited a large interdisciplinary team of more than ten experts with different technical and geographical expertise; on the other hand, we ensured that almost all (98 percent) of submissions were seen by at least three evaluators in each round. Where variance between average ratings exceeded a value of 1, submissions were inspected individually to understand the source of divergence. In fact, evaluators disagreed very little. Most submissions had a variance of less than 1, and we found no significant effect of geography or type of initiative based on a simple ‘distance from average’ calculation (see

Figure 2,

Figure 3 and

Figure 4). Where variance exceeded 1, we inspected individual submissions to look for explanations of disagreement. We found these related to, for example, one evaluator unearthing negative reports through additional desktop research, and disagreement about whether it was ‘too soon to tell’ the degree of transformation. In the second round, more than two-thirds of submissions were rated between 4.25–4.5 average (out of 5), and 100% of submissions had a variance of 1 or lower, implying substantial agreement between evaluators.

4. What Does Urban Transformation Look Like?

Across the literature, transformation—urban or otherwise—is commonly described using adjectives such as deep, far-reaching, radical, long-term, persistent [

6,

7,

8,

31,

32] and sometimes also as systemic and structural [

7,

33,

34], irreversible [

31], non-linear [

32,

35], non-incremental [

12], complex (multi-scale, multi-actor, multi-level) [

6,

32,

36], and inherently contextual and political [

37]. However, despite broad convergence around these abstract descriptors there is considerable ‘elasticity’ [

10,

38] with respect to how transformation is used across different disciplines and in spheres of policy, practice, and science. This has been noted by various publications that map the term’s conceptual and methodological diversity (e.g., [

10,

12,

38]). The growing convergence towards a broad paradigm of ‘transformation’ indicates a shared recognition and desire for more fundamental changes [

39], which are needed, given climate and development imperatives. However, the lack of grounding has important implications because transformation is becoming increasingly institutionalized within the discourses of agenda-setting bodies such as the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), the latest World Social Science Report, and the Future Earth collaborative initiative [

38]. Risks that have been noted are that too much diversity results in vagueness (and therefore a lack of rigor and effectiveness), and that the term could be co-opted by incumbents seeking to maintain the status quo.

This section aims to address the lack of systematic efforts to relate abstract concepts to concrete situations. Our intention is to help bring to life what urban transformation can look like in practice, in order to stimulate discussion and debate, rather than provide the definitive answer to this question. We are doing so by focusing, in particular, on the set of five finalists to the prize, since they provide us with good examples of urban transformation that many—advisors, evaluators, and the jury—agree on.

4.1. Tackling Deep-Seated Urban Problems

Drawing across the five prize finalists, we gain a picture of urban transformation as the outcomes of change processes in which large parts of cities changed in fundamental ways. In each case, this involved overcoming inherited patterns of exclusion, neglect or risk across the various social, technical, and natural systems that make up the city. For example, Durban’s Asiye eTafuleni grew out of a conviction that decades of racist apartheid-era urban design must be dismantled, and that those who suffered most from past injustices are key to reversing disinvestment and neglect. Pune’s waste picker cooperative, SWaCH, challenges the stigmatization and chronic undervaluing of a marginalized group that is nevertheless serving an important function for the city. In Dar es Salaam, the non-profit Amend places the most vulnerable and disempowered road users—school children—at the heart of urban design.

The diversity of finalists indicates that there can exist many pathways to urban transformation, involving diverse actors, goals, and strategies for pursuing and achieving change across many geographies. Amend creates corridors of safety around school zones, connecting these with settlements where schoolchildren live, so that they can reach school safely. SWaCH, on the other hand, is a waste collection service, which covers apartment buildings, individual dwellings, commercial properties and slums across the city. Eskisehir’s transformation encompasses the land and river-based transport networks, as well as large amounts of green spaces. Warwick Junction redefines the city through its gateway, its main transit hub through which the majority of commuters enter the city on daily basis. Similarly, Metrocable in Medellín transforms through connecting the peripheral areas to the main city. Across diversity in physical form and entry points, in each instance the impact that was achieved reversed a preexisting, unjust or otherwise harmful social and environmental situation.

The plurality of ways of tackling urban problems was a striking feature in the entire submission pool, but particularly in the top ranked submissions. It included variety in key protagonists, normative goals, entry points, influence strategies, and specific metrics of success. Leading protagonists ranged broadly and included transit agencies, private for profit and not for profit non-governmental organizations, and public sector administrations. Specific normative goals pursued by submissions included social inclusion, infrastructure upgrades, environmental degradation, disaster recovery, resilience, and climate mitigation, among others. There were also many different sectoral entry points (waste, energy, sanitation, transport, food, resilient infrastructure, etc.) and strategies, often used in some combination (policy change, infrastructure investment, legal advocacy, capacity and training, community organizing, entrepreneurship, etc.). This diversity resonates with the findings of recent reviews [

6]. Given the broad meaning of sustainability, it is perhaps unsurprising that we would argue, that, given the range of sustainability challenges faced by cities across the globe, it is important to accommodate the diversity through which cities can transform. Future studies of urban transformation could explore these points in more depth, investigating whether there is a pattern in terms of geographical effects and city types, and the kinds of urban transformations underway.

4.2. Non-Linearity

An analysis of the prize finalists surfaced several different ways in which ‘non-linearity’ takes place in practice. While sometimes equated with processes of scaling or acceleration, we found non-linearity manifested in ways that were not always progressive and positive. Triggers, such as when administrations change, natural disasters strike, and policy deadlines loom, can bring about accelerations as well as regressions. Triggers can constitute changes in pressures or enabling conditions, and it is also important to note that change always happens in incremental ways all along, but may become most noticeable at particular points of inflection.

For Eskişehir, a trigger point that resulted in accelerated positive change happened when an earthquake struck the city in 1999, killing almost 40 people and damaging the city’s infrastructure. The mayor and his new administration used the crisis momentum to mobilize a broad base of civil society groups, non-government organizationsand business leaders. Importantly, leading up to this moment, the city had already endured many years of decline and decay. The earthquake was a trigger that sparked activity and brought together stakeholders who previously had not felt a shared sense of urgency. A similar window of opportunity opened up in Pune for the SWaCH cooperative. In 2006, the Maharashtra state government introduced a policy deadline for door-to-door waste collection in every city. This provided the urgency for addressing a problem for which SWaCH provided a viable solution. The first memorandum of understanding between SWaCH and the municipal corporation was signed only one year later. Importantly, there had been many milestones leading up to this event (growing policy support for waste pickers, a pilot of the SWaCH model, and a decade of self-organizing by waste pickers), however the deadline imposed by the state provided the moment for SWaCH to establish itself as the vehicle to deliver on the policy mandate.

In contrast, Asiye eTafuleni’s experience in Durban illustrates how trigger moments may not always accelerate progress. The founders of Asiye eTafuleni (AeT)—former municipal officials themselves—left their municipal postings to uphold the vision they had for Warwick Junction, involving the inclusive governance of public space. They did so as the mood towards informality in Durban’s city center was changing within the local administration. When the city suddenly announced plans to demolish a section of Warwick Junction in the lead up to South Africa’s 2010 World Cup, the vision and approach that had begun to take root came under threat. To preserve the market, AeT pivoted towards community organizing, legal education and advocacy to preserve the market, a necessary step before resuming efforts to redesign the area. The events surrounding the World Cup were a trigger that heralded a regressive phase, with complicated implications for the transformative impact of the initiative. This finalist’s experience illustrates the importance of taking into account both positive and regressive directions of change when seeking to understand the importance of individual events, initiatives, and other larger forces.

4.3. Contextual and Relative Shifts

Rather than marked by transition, in the sense of a ‘threshold’ that is clearly crossed [

13], the finalists illustrate urban transformation as a deeply relative and contextual phenomenon that involves the aggregation of multidimensional changes. While there is no universal agreement in the literature, explicitly or implicitly, transitions manifest as a measurable ‘transitional’ threshold of change that can apply in equivalent ways across several instances. For example, transitions are often technological in nature and include major societal changes in which clear inflection points occur, such as the transition from cesspools to sewers in the 19th century [

40], or the evolution of gas and electricity networks [

41] and water supply [

42]. To illustrate the contrast with transformation, one could think of a transition to renewable energy technologies in two countries. Using a threshold of reaching 50 percent generation capacity in the energy mix as a marker for transition would in itself not indicate the magnitude of the contextual shift that has taken place. Whether reaching 50 percent constitutes a large transformation would depend on the starting point—if the energy mix was already at a 40 percent at the outset, this would imply a smaller transformation than if the starting point was 15 percent. In our view, transformation and transition are not mutually exclusive terms, but they do point to different ways of marking change.

In our experience, transformation became knowable by considering the difference between two points in time and space that act as reference points. For example, in the case of the Eskişehir Urban Development Project, the points in time are 1999 (pre-earthquake) and 2018. The big transformation that took place in this period was to turn a city suffering from post-industrial decline and decay into a bustling university and tourist town visited by local and foreign tourists and students, over the course of almost two decades. Both a qualitative and quantifiable shift in specific indicators took place during this time—residents’ access to low carbon transportation and anchor institutions, green space per capita, reduced travel times and cost, increases in tourist numbers and revenue for local businesses, as well as derivative indicators of municipal financial health. Similarly marked changes, unmistakable to evaluators and jury members, were observed in the other finalists too.

During the evaluation, the criterion of ‘problem-solving’ aimed to capture this contextual, relative shift—specifically, the extent to which the original problem a city had been facing had been solved. In the case of the finalists, these ratings were high, meaning the initiatives both targeted as well as effectively tackled an important urban problem, such as decline, disinvestment, lawlessness, and crises of waste and road traffic injuries. This can be contrasted with others in the wider pool of submissions. Many either did not address one of the major urban challenges of the city, or had not been effective in addressing and reversing it. For instance, one initiative from North America had received generally high rankings (it had established itself and even grown, and had some environmental, social and economic benefits), however, evaluators expressed doubts as to whether this initiative was in fact targeting and therefore contributing to tackling and reversing one of the key urban problems this particular city was facing. Placing the initiative in its urban context revealed its transformative impact to be relatively low.

In order to effectively analyze transformation, it is crucial to set spatial and temporal reference points, and to collect data on the ‘before’ picture of an urban area in order to understand the scope of the problem and contextualize the impacts of an initiative. We used the same principle across the other evaluation criteria. For example, the criterion of ‘spatial extent’ aimed to capture whether the initiative had had localized impacts on its project site, or impacted several parts of the city, or the city as a whole. Analyzing transformation relative to a baseline situation helped gain a deeper understanding of the relative merits of the submissions.

4.4. Types of Transformation

In seeking to capture the plurality of ways that initiatives can transform in their own deeply contextual and relative ways, we found merit in the use of evaluative approaches such as the scale we developed for the prize. Building on our experience, we further elaborated a framework for capturing different ‘types’ of urban transformation, continuing the logic of the evaluation scale. This kind of approach helps find meaning and nuance within single examples as well as build bridges across substantially different urban transformation cases. Based on our analysis of the finalists, we derived the following dimensions of transformation in which we observed changes (see

Table 1 for a detailed analysis):

Physical environment—changes to land use, the built and/or natural environment of cities, including new infrastructure and/or public spaces, the upgrade and maintenance of existing structures, and changes in externalities (e.g., reduced GHG emissions, waste collected and processed).

Institutional structures and routines—changes to institutional arrangements, practices, and laws, including new and strengthened governance structures and enterprises, planning approaches, agenda setting on new priorities, and standards, data, legal reform and precedents.

Financial money flows—changes to the type, origin, and destination of money flows, including public and private finance, such as municipal finances, market-rate and concessional funding and finance, land values and property prices, investment incentives for desirable activities; and household level impacts on financial inclusion, and the cost of living (housing, commuting, food).

Behaviors and daily life—changes in patterns of behavior in daily life, such as commuting and transportation patterns, consumption practices, access to economic, social, and recreational opportunities, increases in public safety (traffic, violence), and service coverage.

Perceptions and mental models—changes that could affect a range of stakeholders, such as local business owners, residents, visitors, public officials, community members and leaders, youth, in their attitudes towards social issues and self-perceptions, including awareness and support for new agenda and policy priorities, new social and public narratives.

Using an evaluative framework designed to disentangle nuances of types of change provides an analytical approach to capturing the contextual and relative nature of urban transformation, highlighting the multi-dimensional character of ‘transformative’ change.

Table 1 provides a detailed breakdown of physical, institutional, financial, behavioral and perception changes that were identified in the cases. Using these dimensions, and combining them with the characteristics of plurality, non-linearity, and contextual and relative change, gives an increasingly layered picture of what urban transformation can look like. It helps to develop nuance in relation to different ways that cities change, and about how simultaneous changes in several dimensions can build up to a transformation that is larger than the sum of its parts.

However, while the finalists of the prize are deemed examples of ‘transformative’ changes, not all change is necessarily ‘transformative’ or ‘transformational’ [

27,

28,

30] to the same degree. Projects and initiatives—i.e., deliberate and strategic interventions—interact with larger forces shaping the city, such as population growth, technological innovation, and changing employment, housing and investment patterns. As a result, some contextual shifts will be deeper than others. Changes in one dimension may in themselves not constitute deep transformation, however the degree of transformation will be stronger and deeper the more progressed the change between two moments in time is along the degrees. We hope to deepen our analysis of transformative urban initiatives in the future to include a spectrum of ‘degrees’ of transformation, through an analysis of the broader pool of (non-finalist) submissions, and by drawing on other projects and initiatives beyond the prize. We propose that a fruitful avenue for deeper analysis will be to develop and deepen the approach of working on a spectrum of ‘types’ and ‘degrees’ for analyzing urban transformation in practice.

5. Conclusions

Sustainable urban transformations—deep, far-reaching changes in how cities feel and function—are needed. Yet, despite good efforts and intentions, there is still too little empirical evidence of such dramatic changes occurring in practice. Without establishing conceptual markers for urban transformation, there is a risk that the term remains little more than a catchphrase [

32]. This is particularly important because a ‘transformation’ paradigm is beginning to take hold in research, policy and funding practice, often without grounding in sound evidence. More than one billion dollars are already being invested in urban transformation research and implementation [

11], and much of the needed urban transformation should occur in regions of the world where evidence is scantest [

6,

43].

To add to the evidence base on urban transformation, we focused in this paper on one of the questions at the heart of the normative urban transformation agenda: what does urban transformation look like in practice? In answering it, we drew on the full spectrum of the competition-based approach, including the rounds of evaluation, site visits, and jury deliberation, and focused our analysis on the five instances of deep impact that the competition surfaced. The process of running a major competition challenged us to develop an evaluative framework for assessing real world urban transformation, and enabled us to draw on an unusual case selection method for a comparative qualitative analysis of five implementation cases. The competition-based approach for sourcing instances of urban transformation yielded an expert-recommended and crowd-sourced selection of real-world examples of urban transformation. While the pool of submission constitutes a semi-self-selected sample, the multi-round evaluation process provided a reasonable degree of confidence in the quality of submissions as the basis for carrying out an investigation into the question of what urban transformation looks like in practice.

Based on a focus on the five finalists, we propose that it is possible to make meaningful statements about urban transformation. We described urban transformation as encompassing a plurality of contextual and relative changes, which may progress and accelerate positively, or regress over time. To find meaning within single cases and across several cases, an evaluative approach that considers varying ‘degrees’ and ‘types’ of urban transformation is proposed, which corresponds with several academic perspectives on evaluating transformative change processes [

44,

45]. Therefore, a key takeaway for those seeking to better understand and use the concept of urban transformation is to analyze transformation relative to a baseline situation and identify broad types, degrees and indicators of transformation that can be observed and measured through time and space.

Demystifying urban transformation in the real world is just a first step towards helping different change agents transform cities. While it is important to break ground on such foundational questions, it is even more critical that foundational research is translated into practical resources for designing, implementing and evaluating urban transformation projects, initiatives, programs, and policies. A dedicated focus on translating insights into pragmatic approaches, tools, checklists, diagnostics is needed, which can hopefully be supported by a greater alignment between the language, actions, and funding agendas to help match knowledge needs with research priorities and funding calls. To deliver more effective interventions at a faster pace, it is necessary to enhance the transformative capacity of key actors, including by increasing awareness of what is happening around the world, inspiring and attracting talent into the field, and improving the technical, managerial and coalition-and consensus building skills of potential change makers across the spectrum of potential action.