4.1. Endangered State of Chengdu Lacquer Art

Chengdu lacquer art is one of the earliest lacquer art in China and one of the four largest lacquerware in China; it was also included in the first batch of national intangible cultural heritage lists in 2006 [

11]. As early as 3000 years ago in the ancient Shu period, Chengdu’s lacquerware craft reached a high level. During the Warring States Period, Chengdu lacquerware was spread to many parts of China as a cultural and commercial product. From the existing archaeological data, we can witness the superexcellent workmanship and glory of Chengdu lacquerware at that time. Chengdu lacquerware is exquisite in workmanship, and most of the working procedures are handmade. The bottom body is made of fine-texture and dehydrated logs, and the craft involves carving, inlaying, filling, tracing, pushing, painting, pasting, and other methods. The most distinctive one is “three carving and one etching” (carved solder wire halo color, carved flower and filled color, carved and filled hidden flower, broach needle etching). Through the analysis of documentation and interview materials, the following was found:

Influenced by policies, Chengdu lacquer art has experienced several ups and downs since modern times. The first stage: since the founding of the People’s Republic of China, all trades and industries were flourished and thriving, and Chengdu lacquer art, a significant component of Chinese lacquer culture, was fully restored and developed. Chengdu Arts and Crafts Shop was established in 1954, and Chengdu Halogen Lacquer Shop was formally established in 1956. The number of skilled workers expanded to 40 and reached 200 in 1960. This period was the most prosperous period of Chengdu lacquer art after liberation.

The second stage: in 1963, the higher authorities decided to abolish Chengdu Halogen Lacquer Shop. The vast majority of skilled workers were transferred from the shop, retaining 49 people engaged in paint processing for buildings and furniture, and only 9 people were left by 1965. From 1966 to 1973, for well-known reasons, the cause of arts and crafts was basically at a standstill. To meet the needs of politics, many arts and crafts with prominent political themes were produced for the sole purpose of “three loyal to” activities. In this way, Chengdu lacquer art was once again in trouble, almost destroying Chengdu lacquer art.

The third stage: in 1975, the Ministry of Light Industry decided to resume the production of lacquerware in Chengdu and set up a factory in Jinhe Street, Chengdu. Upon examination of the competent department and the company, 50 new workers were selected on the basis of merit, and the old artists—Chen Chunhe, Yu Shuyun, and Zhang Fuqing, among others—led the learning workers to learn lacquering techniques, respectively engaging in woodworking, painting, decoration, paint making, and so on. After more than 30 years of hard work, Chengdu lacquerware craft, which had been lost for many years, was fully transmitted and protected.

The fourth stage: in 1999, Chengdu Lacquerware Craft Factory, as one of the first batch of small and medium-sized state-owned enterprises and urban collective enterprises in Chengdu, was transferred to Qingyang District by the head of Chengdu Light Industry Bureau. Now, it is managed by Shaocheng Street Office, pushing Chengdu lacquerware to the top of market economy and letting it run its own course. Because of the fact that traditional crafts are not suitable for market competition, Chengdu Lacquerware Craft Factory ceased production in 1995 and more than 80 technicians were laid off.

The fifth stage: in 2000, out of the sense of historical responsibility for the transmission of Chengdu lacquer art, enterprise employees and masters of arts and crafts worked together with the newly elected factory director and leadership team resumed the production of traditional Chengdu lacquerware. At present, Chengdu lacquer art is still in deep trouble because most of the skilled workers have found another job or retired, and only 20 skilled workers are still engaged in lacquer.

4.2. The Living Transmission of Chengdu Lacquer Art Training Institute

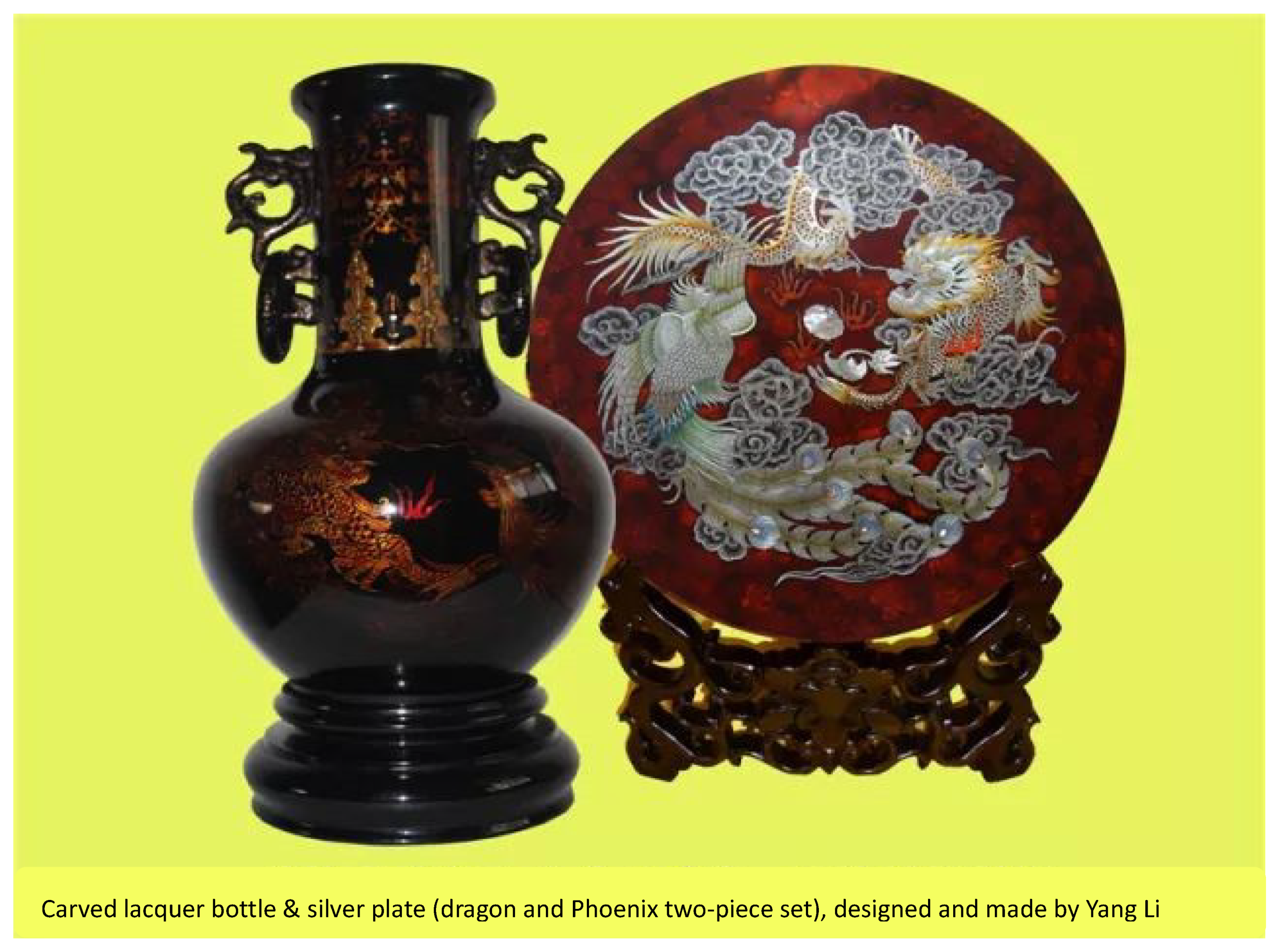

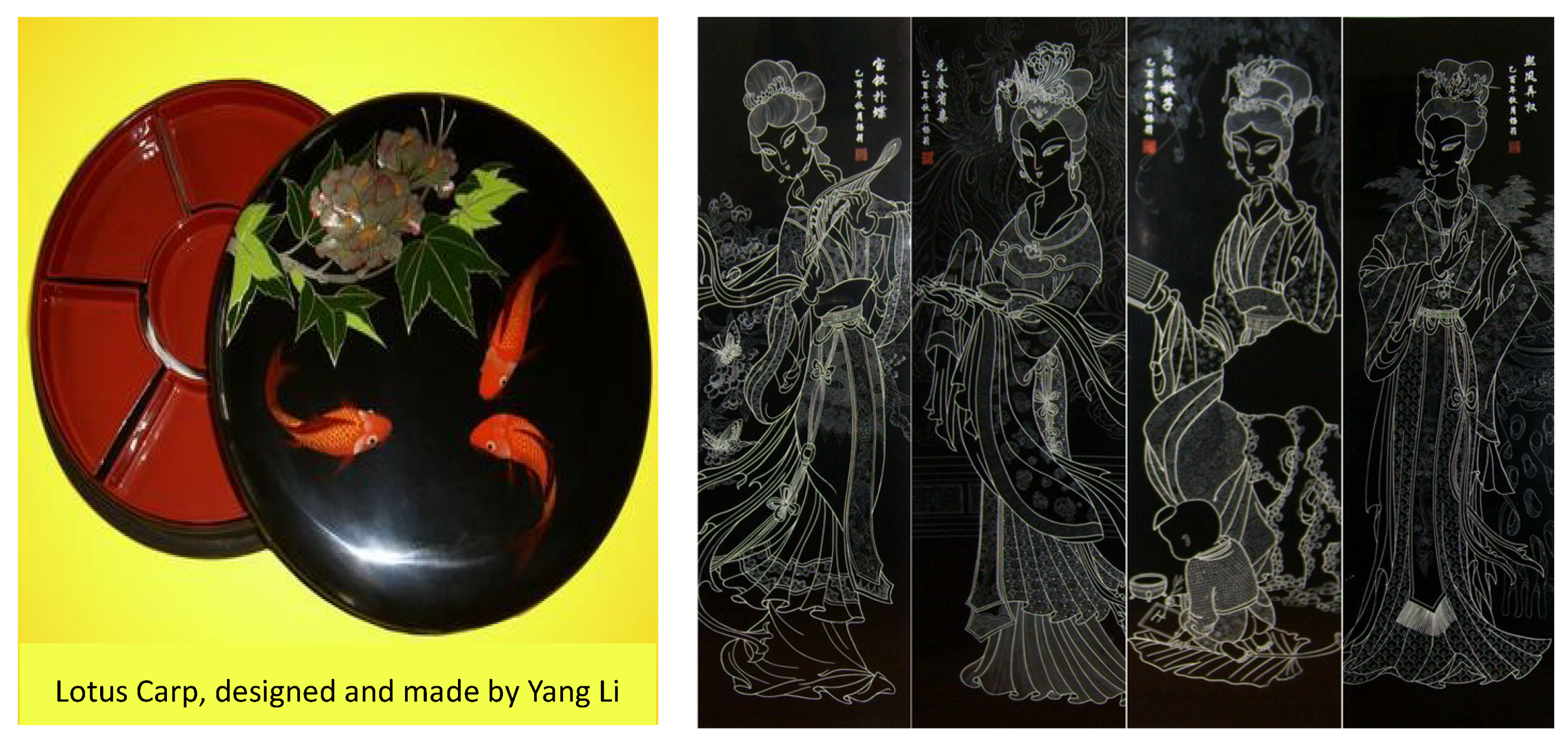

Established in 1995, Chengdu Lacquer Art Training Institute was an outstanding representative of the transmission and development of Chengdu lacquer art. Its director, Yang Li (also known as Irgen Gioro·Erqian), born in 1949, Manchu, is the transmitter of “Chengdu Lacquer Art”, China’s first batch of intangible cultural heritage. She has been engaged in lacquer art for 43 years and is renowned as a lacquer artist and a master of Chinese arts and crafts. Her works have won a dozen national-level and provincial-level awards such as China’s Hundred Flowers Award for Arts and Crafts and China’s First Lacquer Painting Exhibition Award for Arts and Crafts. She has produced large-scale lacquer paintings “Hongtong White Crane”, “Lotus Carp”, and many other works for the Sichuan Hall of the Great Hall of the People, which have been collected by Chinese and foreign museums, or given to foreign distinguished guests as state gifts. Moreover, her artistic achievements have been recorded in ancient books such as “Dictionary of Chinese Contemporary Literary Celebrities”, “Complete Works of Chinese Modern Art, Lacquerware”, and “Excellent Collection of Chinese Masters of Arts and Crafts”. According to the interviews, since she officially started the first lacquer art class in 2004, she has recruited apprentices every three years and has successfully trained more than 30 apprentices so far. The apprentices learned the main processes of design and creation, lacquering, decoration, cleaning, and polishing of lacquer art, as well as more than 30 traditional decoration techniques, and their works won more than 20 awards at or above the provincial level (part of the lacquer works is shown in

Figure 1). Now, some outstanding apprentices, such as Lv Xingzhen, Huang Jinhong, Wu Xungui, and so on, have also begun to recruit their own apprentices and continue to impart lacquer art skills. Through interviews, they learned about the whole process of live transmission of Chengdu Lacquer Art Training Institute, as well as some challenges in its transmission.

Viewing from the origin, the transmission behavior of lacquer art originated from the recognition of skill value by the master and apprentices. The transmission path is transferred by the master, the main body of knowledge transmission, and guided by wishes, motives, incentives, and so on, to select appropriate transmission methods to transmit knowledge and skills to the recipients, thus completing the process of “transmission” [

22,

30,

32]. However, it was mentioned in the interview that,

“at present, the skilled workers are relatively old and their energy, physical strength and eyesight are not as good as before. Among the existing artists, 5 of the 8 masters of arts and crafts in Sichuan Province have retired and 3 are on the job; all of them are over 50 years old; there are 23 outstanding skilled workers, only 10 are on the job now, and most of them have not recruited apprentices in the past 20 years. Furthermore, some masters in the industry are rather “conservative” and unwilling to recruit apprentices, and they may always let their apprentices do some odd jobs after recruitment. Faced with the demand of “inlaying artifacts by means of chasing with hundreds of skills and thousands of workers”, Chengdu lacquer art, which has been praised as “a unique skill throughout the country”, is really on the verge of death. If it is not rescued and protected, it will be deserted”. Meanwhile, prospective recipients will decide whether to conduct knowledge survival after multiple considerations [

5,

33]. Some interviewees said, “

many people are not willing to engage in lacquer art industry because of the many basic processes, complex production processes, great labor intensity, high technical content and low labor remuneration in lacquerware production”.

Thus, only when both parties have the willingness to transmit can the transmission relationship be truly established, and then the transmission behavior can occur with the mutual cooperation and guidance of the transmission parties. Moreover, whether the master and apprentices have their own “bright spots” to attract each other to choose and recognize themselves is also the key to the establishment of the transmission relationship [

25]. Just as the master intends to select the students with “good painting skills and good moral character” from the many students visiting the master as apprentices, the apprentices will also find those boasting “great reputation and excellent works” among the many lacquer art masters as teachers. Hence, skill transmission is the matching and collection of master and apprentice’s transmission capability and will. To some extent, the first stage of skill transmission is a process of mutual identification and mutual exploration between the initiator and the successor.

Upon establishment of the transmission relationship, the formal process of skill transmission will also begin. Through participatory observation, it is found that in the process of working together, apprentices will try to understand the master’s thinking process, observe and imitate master’s behavioral style, and gradually master and internalize the external behavior through continuous practice [

34]. The master will offer appropriate guidance and help to his apprentices, helping them to understand and grasp the basic principles and know-how of their experience and skills through personal demonstrations and lectures, among others [

30]. As for the whole process of skill formation, it has certain stage characteristics based on participation observation and interviews [

16]. First of all, the master imparts some basic knowledge of lacquer art to his apprentices, such as introducing the materials and tools, processes and flows needed for lacquerware making, and displaying some typical techniques (See

Figure 2). This is the reserving stage of skill formation, requiring apprentices to form visual representations and rough perceptions in relation with knowledge and skills in their brains. There will be some difficulties in this process, for instance, the interviewee mentioned the following:

“Since Chengdu lacquer art is mainly a handmade craft, which needs to be constantly adjusted in line with the conditions of raw materials, body shape and climate, the technical know-how discovered and summarized by artists in practice can only be applied under specific conditions, thus it is hard to summarize in modern technical language. Besides, most artists are old and have different cultural levels and expressive capabilities, so systematic summary must be carried out in practice, which will be a time-consuming and labor-consuming systematic project. Moreover, master and apprentices have their own creative ideas, which needs to be constantly coordinated”.

Next, the organization and coordination of cognitive turning action, static knowledge turning to dynamic operation, and turning action of individual action are needed to form a coherent preliminary action system [

22,

30].

In practice, “the master taught a skill once a week, and apprentices first learned lacquer making at that rime. Chengdu lacquer art was mainly characterized by natural wood and raw lacquer as the main raw materials, but raw lacquer was expensive and it is difficult to find resources. Furthermore, some people are allergic to raw lacquer and have blisters on their bodies, so they have to give up the study of making lacquer. The body skeleton of lacquerware is the foundation of lacquered ware, which is crucial to the shaping and function of lacquer ware. In specific artifacts, transmitters often adopt different body skeletons and manufacturing methods based on the shape and function of the artifacts. After the body skeleton has been made, the next process is the cutting and making of the lacquer body and the paint gray. The quality of the paint gray affects whether the refined art works can be well preserved, whether they will crack in the later stage, whether the pits will be formed by reason of the wet paint in the polishing process, etc.”. Therefore, the master’s willingness to teach and the extent to which he teaches his apprentices, as well as the extent to which the apprentices put into practice, exert a significant impact on the quality of lacquer art works, and are also in relation with the transmission of lacquer art.

Another interviewee mentioned that, “

the tools used in the process of making lacquerware are mainly hand tools, which are often made by artists based on their needs in the process of making the craft and are not of complete universal property” (See

Figure 3). However, by reason of the industry’s low efficiency in recent years, these unique tools and instruments have worn down by the years without repair and many special tools are now facing the crisis of extinction and disappearance. Take the human hair paint brush as an example. In the past, the old master made the brushes himself and distributed them to his apprentices. Now there are only a handful of technicians who can make human hair brushes. Because of the scarcity of human hair resources, it is hard to use human hair paint brushes now. It is also pretty hard to find manufacturers or individuals of ox horn shovels.

After long-term study, repeated operation, and practice, various independent, partial, and fragmentary skills are gradually connected into a complete, comprehensive, and automatic skill system [

22]. Disciples began to form their own styles of creation and were able to create independently. For instance, some were good at making daily necessities such as vases, plates, and combs, and others were specialized in making fashion supplies such as lacquer paintings, jewelry, and bags… Respondents generally expressed the following:

“There are as many as hundreds of manufacturing processes from paint making to body making, paint gray application, painting, polishing and refining, as well as 20 or 30 simple ones. For example, it takes years of experience to master the thickness of paint gray applied each time, not in one day or in a few months. While only Chengdu Lacquerware Craft Factory can manufacture exquisite lacquerware in full accordance with the traditional Chengdu lacquerware art, and only a few dozen people really master the traditional craft”.

Viewing from the transmission results, the apprentices interviewed said that “

if we can make more than 30 vases a year now, we can exchange for a year’s worth of materials by selling a fine one”, while some other apprentices “opened a studio in Landing Youth Art Village to make lacquer vases, tea sets, and some accessories, such as bracelets, necklaces and combs, to feed themselves”. Despite that the Wenshu Temple, where lacquer arts are taught, has a special store (See

Figure 4) to sell lacquer art products, the products are mainly consumed by acquaintances or privately ordered, so the sales volume is not particularly large. Because of long working hours and expensive materials, the price of lacquerware is relatively high, but it is not easy for people to recognize this value. Apart from that, as the traditional products of folk lacquer art workshops and transmitters of traditional skills cannot enter the popular consumer market, the traditional lacquer art has declined in the era of industrialization and modernization; besides, as they do not have the ability to create new products for the aesthetic tastes of the new era, the traditional skills they have mastered are difficult to find space for “application” and “sustainable” development in real life, and even have been forced to the brink of extinction.

Relying on the cases of Chengdu Lacquer Art Training Institute, the current research has a relatively profound understanding of the whole process of live transmission of lacquer art. From the analysis of “the establishment of transmission relationship”, “the process of skill formation” to “the result of transmission”, we have found the survival situation of lacquer art transmission and the key problems affecting live transmission, which can be summarized as follows:

Problem 1. As for masters, most of them are older and have less energy, physical strength, and eyesight than before; their knowledge level is rather limited and it is hard for them to provide the necessary conditions and places for the transmission of skills. Either they cannot recruit apprentices or their own transmission willingness is not high.

Problem 2. On the part of apprentices, they may be allergic to raw lacquer and have limited time and energy. Apart from that, the complex production process, great labor intensity, high technical content, and low labor remuneration make them unwilling to engage in the lacquerware industry.

Problem 3. In terms of transmission relationship, the time and energy input of the master and his apprentices are not exactly the same either, and there is a certain generation gap between the new and old transmitters. The interaction and relationship between the two sides need to be continuously run-in and further improved.

Problem 4. With respect to materials/artifacts, raw lacquer is expensive and it is hard to find the resources. Special tools such as traditional paint brushes and ox horn shovels are now facing the danger of extinction and disappearance. To a certain extent, it hinders the efficient and large-scale production of lacquer art.

Problem 5. In terms of the inheritance idea, the old artists attach importance to “skills”, while the young transmitters attach importance to “arts”. Most of the inheritors’ creation tends to be traditional and conservative, which renders it difficult to create new products considering the aesthetic taste of the new era.

Problem 6. After the transmission is over, the lacquerware products produced are mainly sold through acquaintances or stores, lacking systematic marketing promotion strategies, and the sales volume is not high and the products cannot enter the popular consumer market.