1. Introduction

The earthen defensive heritage of southeast Spain is recognised for its heritage value. As a result, it has been granted the maximum level of protection available under national legislation. However, the fact that these assets are currently in a poor state of conservation is incoherent with this position. The methodological approaches currently being researched centre on proposals for the sustainable preventive conservation of these structures. As part of this approach, and in order to enhance the value of this Cultural Heritage, different perspectives should be considered and how these positions interact should be examined. Specifically, aspects relating to preventive conservation and those associated with the socioeconomic management of the heritage asset need to be considered. Sustainable preventive conservation means that the heritage landmark becomes viewed as a resource which contributes to the socioeconomic growth of the surrounding area. It could be used and developed, it would undoubtedly act as an agent of economic growth, wealth, and employment but it might also be the key factor in the social and economic development of an area (quality of life, feeling of belonging, identity, etc.), which would be of particular importance to areas with limited economic activity. By combining adequate economic management with sustainable management, a portion of the profits generated by the asset could be reinvested into preventive conservation activities.

The design of heritage conservation strategies considers heritage as a resource for economic development, but when it does not receive this attention, the corollary is that it becomes marginalised and destroyed [

1].

According to [

2], public interest or lack of interest in heritage sites is greatly dependent on their state of conservation. It is scientifically accepted that Cultural Heritage assets can contribute as capital goods to socioeconomic development [

3], as they have the inherent potential to become tourist attractions, thus contributing to local development [

4].

Therefore, leveraging these heritage resources in a sustainable and responsible manner presents an excellent opportunity to improve people´s lives, both in terms of material gain (wealth, employment, innovation, entrepreneurship) as well as in nonmaterial ways (identity, participation, training, satisfaction, enjoyment, etc.) [

3].

In order to achieve this, most modern societies are committed to and concerned with their heritage worth [

2]; as a result, there has been an increase in research in the last few years which approaches heritage appraisal from different perspectives and using different methods [

2,

5,

6,

7,

8,

9,

10]. One perspective that has gained particular attention and relevance is that of consumer-based brand equity, that is, the consumer’s appraisal of the brand heritage as regards heritage landmarks.

The American Marketing Association defines a brand as the “name, term, sign, symbol or design, or a combination of them intended to identify the goods and services of one seller or group of sellers and differentiate them from those of other sellers.” Brand management is the consequent effort “to create, maintain, protect and improve” [

11] a specific brand to ensure a sustainable competitive advantage. As with any brand, those responsible for managing it have an inherent obligation to preserve and improve its reputation and prestige.

In the field of heritage tourism, this translates as guaranteeing the authenticity, integrity, and preservation of the sites and making them available for tourists to visit and enjoy [

12], whilst simultaneously taking into account the sustainable development agenda outlined by the World Tourism Organization in 2017 [

13]. In fact, the United Nations declared 2017 as the International Year of Sustainable Tourism for Development due to its potential for development worldwide. In the context of brand strategy, heritage landmark, brand management could contribute to tourism growth in a sustainable manner, yet also guarantee conservation of the asset and the best possible outcomes for the local community [

13].

Although “brand” has become a buzzword in academia as well as in commercial settings in the last few years, knowledge has concentrated on assets and commercial services and less so on locations and specific tourist destinations [

14]. However, in recent years, the strategic needs of destination managers as well as the need to broaden knowledge about the brand´s effects have led to the emergence of research on the destination as a brand [

15,

16].

In the context of tourist destinations, visitor loyalty is considered to be an important factor in the successful development of a destination. Numerous studies carried out in different settings (country, states, city) examine the antecedents to tourist loyalty, including motivation, destination image, quality of travel, perceived value, and satisfaction [

17,

18,

19,

20]. Place attachment and tourist engagement have also been considered to be predictors of loyalty to the destination [

21,

22,

23]. More specifically, these predictors have been widely examined in the contexts of leisure and recreational destinations [

24] and heritage sites which are established and well-known tourist destinations [

25]. According to [

4], such heritage resources have the potential to become attractions and contribute to the sustainable development of the area. However, to date, and as far as we know, no studies have been carried out which examine the antecedents of loyalty to heritage sites which are not already established destinations.

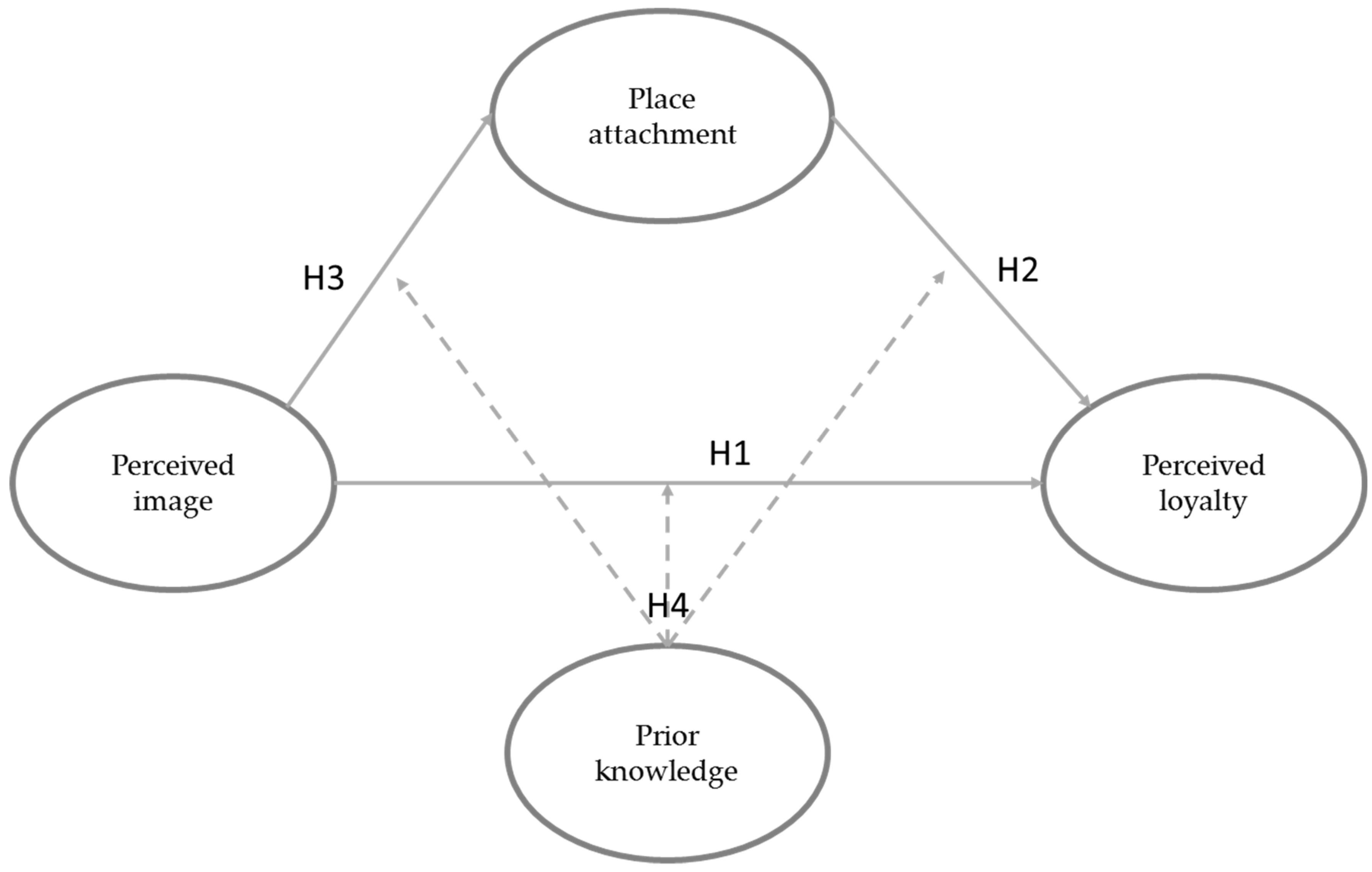

Therefore, the main objective of this article is to examine if loyalty to a heritage site arises as a result of the perceived image that individuals have of it, as well as to what degree place attachment mediates the relationship between the effect of image and loyalty. This main objective is supplemented by an analysis of the moderating effect of knowledge about how the heritage site affects these associations.

By so doing, this paper seeks to contribute to the literature on heritage landmark (Goods of Cultural Interest) brand management in several ways. Firstly, further what is currently known about which factors determine loyalty to heritage sites. Secondly, assess the role that perceived image and place attachment plays in developing loyalty to this brand type. Thirdly, examine the degree of knowledge about the heritage site as a moderating factor associated with the antecedents to loyalty. As proper management of the brand leads to increased loyalty to the heritage site, it becomes more likely that it will be visited and recommended. The resultant increased income to local communities, especially those with scarce economic resources, in turn facilitates the sustainable management of the heritage asset. All of these factors in turn help to protect and preserve the heritage landmark for future generations.

5. Conclusions

The purpose of this paper is to assess a theoretical model of the development of loyalty to a heritage landmark, on the basis of the perceived image of the heritage site and place attachment to the heritage site. Loyalty to a tourist destination is key to how the tourist behaves with regards to that destination, demonstrated as their intention to visit and how likely they are to recommend it [

48,

51,

54,

55]. Of the factors which contribute to the development of loyalty to the destination, destination image should be noted [

17,

23,

49,

55,

86,

88,

89].

This paper contributes to current understandings of the factors which determine how loyalty to a heritage site is developed and the role played by the degree of knowledge.

In the first place, our findings show that the heritage landmark image has a direct, positive effect on the development of loyalty, and as such, is an antecedent to loyalty towards the destination, in line with the academic literature [

49,

55,

81]. In addition, place attachment to the heritage site has a direct, positive effect on the development of loyalty, as has been found by other authors [

23,

66,

67,

68,

69,

70], being antecedent to loyalty. Therefore, increased loyalty is found where there is greater place attachment to the heritage site. Likewise, findings show that image has a direct and positive effect on place attachment to the heritage site, as has previously been asserted [

69,

94]; therefore, as the image of the heritage asset improves, so place attachment to it increases. An additional conclusion derived from these results and of equal relevance, the association between the perceived image of the Torre de Romilla and place attachment does not appear to be affected by the degree of subjects’ prior knowledge about the heritage landmark, counter to what would be expected according to [

97]. These results seem to indicate that the link between the heritage landmark and attachment is strong regardless of the degree of knowledge about the heritage site.

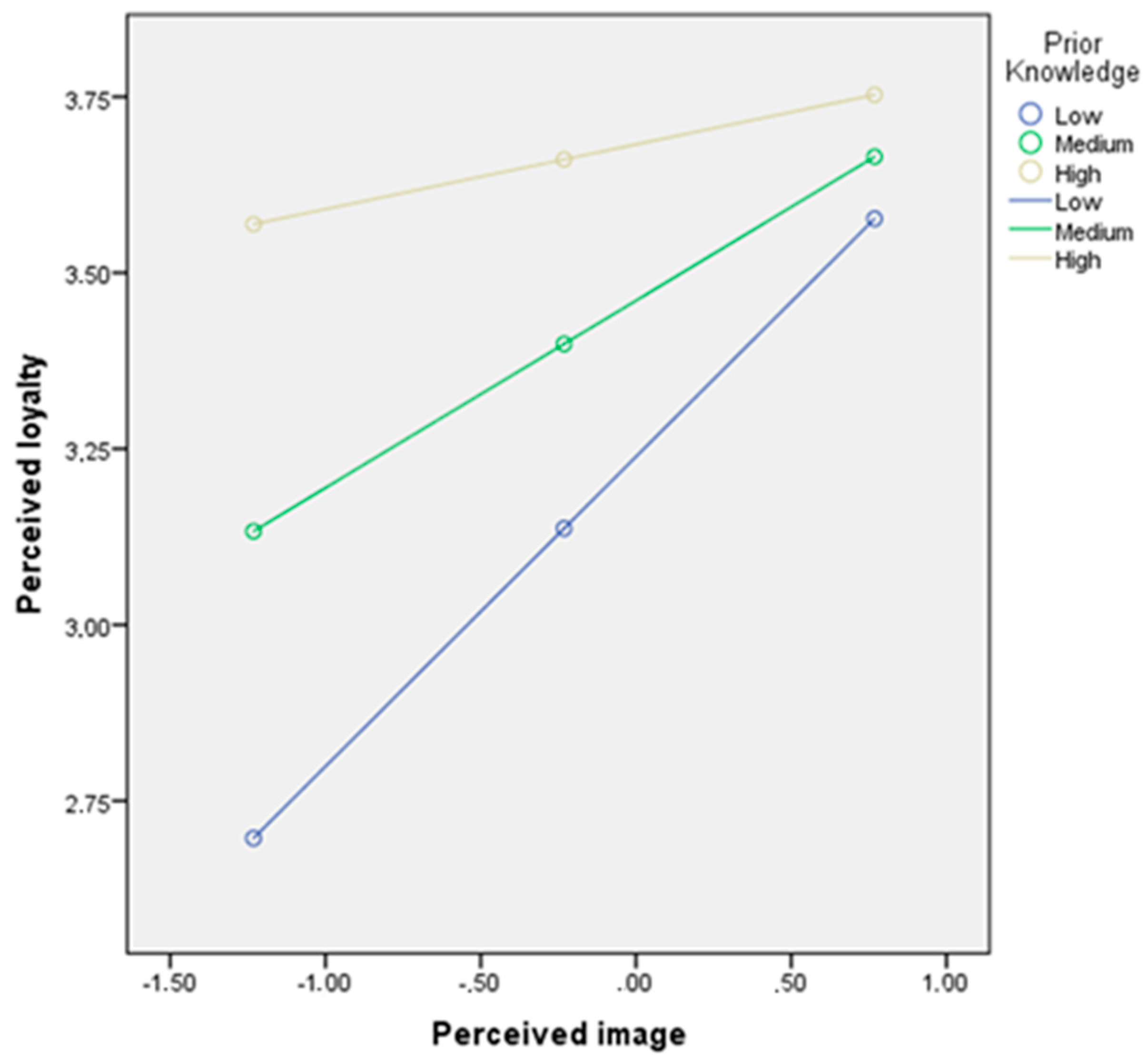

In the second place, our findings show that the degree of knowledge regarding the heritage site does in fact moderate the existing direct relationship between the perceived image and loyalty. This is demonstrated by the fact that when there is a small degree of knowledge about the heritage site, the image perceived to it is a greater determinant of loyalty towards it; in this case, loyalty increases as the perceived image of the asset improves. However, in the case of a large degree of knowledge about the heritage site, image is not the determining factor in the development of loyalty to it. The results indicate that those who know the Torre de Romilla (either because they have visited or from other sources of information) had a more positive image of the heritage site and were more likely to visit and/or recommend it, in line with [

105]. However, counter to the predictions, the effect of place attachment on the association between the asset’s perceived image and interest in or likelihood to visit the Torre de Romilla is influenced by the degree of knowledge, contrary to prediction.

6. Implications for Management

Our findings also have considerable implications for tourist destination heritage site managers. On the one hand, we have found that a positive perceived image of the heritage site can lead to strong attachment, which paves the way for greater loyalty [

23,

63]. On the other hand, the findings also suggest that, in order to maximally affect loyalty (intention to visit and recommend), managers should take proactive action to increase knowledge about a site, make investments to improve its conservation, and promote the site to a target audience.

Heritage managers should consider all aspects related to such heritage in an integrated manner. As note by [

36] citing [

119] notes that successful heritage tourism threatens the very heritage resources that are the basis of such tourism. Consequently, these managers’ current task is to identify and appropriately respond to strategic opportunities to develop these sites. In line with [

120,

121], the participation and support of key stakeholders is recommended. Developing practices based on insight, and which are in line with the remit of those responsible for heritage conservation and protection, marketing, and administration, will simultaneously achieve a balance in communication directed towards cultural tourism and tourism in general. Applying marketing techniques and increasing knowledge about the visitors’ profiles are essential components of this communication process and go towards ensuring that heritage is accessible and significant for both cultural and general tourism, in line with [

120]. Along the same lines, and as is demonstrated by the results, knowledge regarding heritage assets also needs to be increased. As has been shown, greater knowledge leads to greater attachment, which increases the latter’s effect on loyalty. These measures would allow the protection and appraisal of cultural heritage to act as a strategic engine for local development [

122], without compromising the site’s authenticity, as posited by [

120].

Therefore, tourist destination planning and management should ensure that special consideration is given to the maintenance and conservation of the natural resources which the tourist offering represents [

123]. Improved conservation of the heritage asset will improve its image, which in turn will lead to increased loyalty. This loyalty is demonstrated by the intention to visit and recommend.

This kind of initiative facilitates citizen awareness in a process of cultural identity, as a feeling of esteem for the site patrimonial that promotes its protection and appreciation, by both the local population and the occasional visitor; participants in the defense and maintenance of sites, as well as in compliance with the elementary principles of their conservation [

124].

7. Limitations and Future Lines of Research

As is the case for any scientific research, the present study presents some limitations worthy of mention. Firstly, this study focuses on presenting a model of the development of loyalty to a specific heritage landmark with the particular characteristics of the “Torre de la Romilla”: A heritage site located in the south of Spain, in the Vega de Granada region and not recognized as a tourist destination, but which is nevertheless a resource which has the potential to become one and contribute to local development, as indicated by [

4].

The question of whether future studies could replicate the findings of this study for cultural assets with similar characteristics is an interesting one. The findings of this study could be extrapolated for analysis and would potentially have repercussions for assets of a similar nature, characterized by a defensive architecture, located in areas with a population of less than 10,000 inhabitants and disadvantaged from the perspective of the availability of human or material resources. If the potential benefits identified by the present study are taken into account, these considerations taken together could lead to improvements in cultural tourism management, general tourism, and the basic social economy of the municipalities and regions in which these heritage landmarks are found

Secondly, a larger simple size would have been preferable; therefore, it is recommended that future studies attempting to replicate this study use larger simple sizes with greater heterogeneity.

Thirdly, future studies should account for other moderating variables such as the subjects’ usual residence, their degree of cultural tourism experience, the frequency of visits to these types of cultural landmarks or, as cultural values could be associated with a destination choice or with attachment [

125], the visitors’ nationality or culture in the case of using samples from other countries.