Socio-Cultural Sustainability of Private Healthcare Providers in an Indian Slum Setting: A Bottom-of-the-Pyramid Perspective

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Background of the Study

2.1. Health-Seeking Behavior at the BOP

2.2. Consumer Choice at the BOP

2.3. Recent Developments in the BOP Paradigm

3. Research Design and Methodology

3.1. Empirical Setting: The Indian Healthcare System

3.2. Quantitative Study

3.2.1. Sampling Technique

3.2.2. Data Collection and Measures

3.2.3. Data Analysis

3.4. Qualitative Study

3.4.1. Selection of Respondents

3.4.2. Data Collection

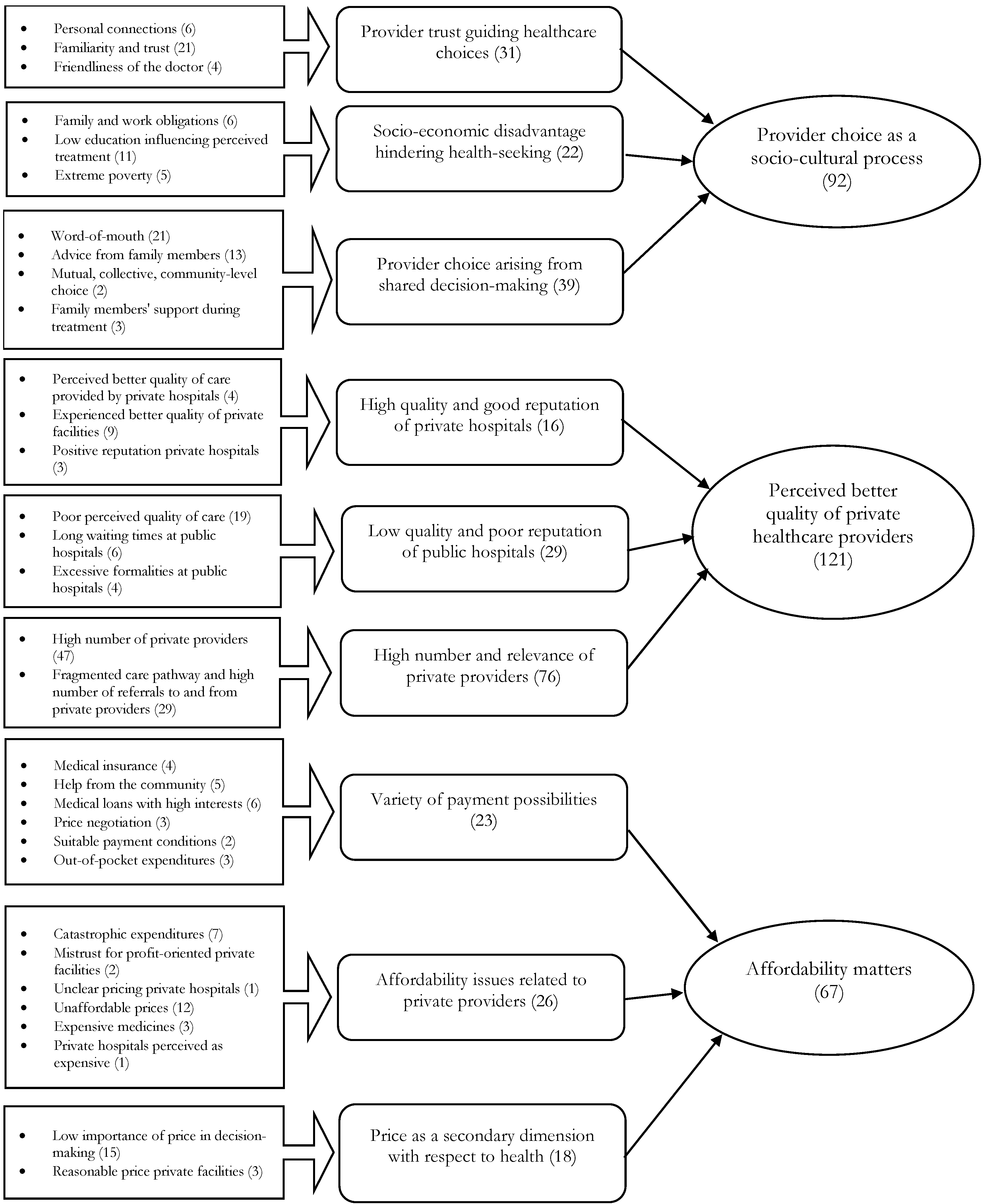

3.4.3. Data Analysis

4. Results

4.1. Findings of the Quantitative Study

4.1.1. Descriptive Statistics

4.1.2. Pearson’s Chi-Square Analyses

Dependent Variable: Private vs. Public

Dependent Variable: Inpatient (IP) vs. Outpatient (OP) Treatments

4.2. Findings of the Qualitative Study

4.2.1. Provider Choice as a Socio-Cultural Process

I am the eldest sister of three sisters—all unmarried. So, I have the responsibility of the house, and of the two younger sisters as well. If I go for the operation, if something happens to my life, who will take care of my house and my two younger sisters? I’ll have some care when my family problems will come down. At that time, I’ll get operated.(Jamuna)

So, from childhood days, father and sons, everyone is going to this hospital, and they get cured by the prescribed medicines; now, they have an emotional touch and good experience. Because we are emotional people…you know. Yeah, so an emotional connection with this hospital.(Abhijit)

Author: So he’s scared about the VS hospital because he fears that they will treat him badly.Translator: Yeah. Not badly, but, ehm, he fears that they want to experiment with his body.Author: Because he is poor?Translator: Yeah obviously because he is poor.(Akshay)

So, everyone has said that Dr. Umesh is good, his treatment is good. We knew that he is good, we are familiar with him and he is very nice. A strong advantage is that he straightaway starts the treatment because he is familiar with the local people here. So he doesn’t always ask to deposit the advance amount first. Everybody really likes him, and he’s a specialist for children. Most of the people who go to him get cured by taking the prescribed medicines.(Rupa)

I think the Latesia [private hospital] is good because the doctor doesn’t think the patient as a patient, he himself seems like they are my near ones and dear one. The moment I was scared to go for angioplasty because I was in a very bad condition; the doctors said it’s curable, think of me as your brother or as your father. At that time, I thought that he is not my brother my father but he is like a god for me. Because when I was done with angioplasty, I was perfectly alright, and he was the one who encouraged me and gave all the motivation and support that I was looking for at that point of time. So I have great respect for him.(Jamuna)

So, they went twice to the government hospital, but their medical problem wasn’t cured, so they decided to visit Bhavanbhai [private hospital], because she’s very popular, and they don’t want to get operated in a government hospital. There, a couple of people died because they believe that most of the people in government hospitals are trainees, they are not the actual doctors. So, they try to keep themselves away; when it comes to the operation, they are scared to get it done at the government hospital.(Preeti)

4.2.2. Perceived Better Quality of Private Healthcare Provision

I have not visited the GH (government hospital), but everyone has a bad experience there, so I prefer not to go. I prefer private. Because everyone is saying they don’t have equipment and personnel, so they have the impression that they will not get proper attention and treatment.(Shanti)

My father needed emergency care, and it took around 2–3 h to actually get the treatment started. I needed to fill up many forms. It took really lot of time for the doctor to attend him. When the doctor came, he just suggested that my father should have gotten a CT scan done first. Now, at the CT scan, there is also a queue, but my father was lying on the stretcher for 2 h. And he was an emergency case.(Raj)

Translator: He’s saying that they had to wait for two days outside the hospital to get in. There were a lot of formalities they had to perform…Author: And they had to sleep outside of the hospital?Translator: Yes, they had to sleep outside of the hospital, in the street.(Soni)

I went to the Civil Hospital. Once there, initially I was told that I had heart problems and I should go to the heart specialist. When I went to see the heart specialist, he said that I had a problem in the kidney. So, this was the experience at Civil. I went in the morning, and by that time, I wasted so much time that it became afternoon, so I just came back home.(Chandan)

So, when we go to the government hospital, we have to stand in a long queue, and then come back home and cook the meals for the family. We can save their time and go to a private hospital and we will get personal attention from the doctors, in the private hospital. In the government hospital, we don’t get the proper answers, and nobody is there to attend us.(Kriti)

I enjoyed watching the TV (television) and the facilities which were clean.…Cleanliness, neat and tidy, because, I mean, we’re living in the street and we do not have our own TV and we enjoy this kind of thing in the hospital. We felt like we’re in a hotel.…We took the general class. And the general class was on the terrace, there were 15 beds. But the cleanliness was good, there was a TV, there was a bathroom. And the treatment was really good, there were nurses visiting every 5–10 min, there were check-ups and everything.(Preeti)

4.2.3. Affordability Matters

Actually, we visited a government hospital. We can’t afford to go to another hospital.(Soni)

So, the point is, we are considering to visit some other [private] hospital, but due to lack of money, we cannot really afford to go.(Meena)

Translator: And the same angioplasty, if she wants to do over there in the private hospital, they will charge INR Indian rupee) 50,000–80,000. The private hospital is for rich people.Author: Did she ever consider to go to a private hospital?Translator: She won’t be able to afford so she didn’t consider. Yeah, so they didn’t. That’s a waste of time to think about that because they won’t afford it.

For the consultancy he did, the doctor charged me INR 450 and he prescribed me a sonography. He charged INR 600. With the sonography they gave me, I went back to the Bhavanbai’s place, and then he told me it’s the appendix, I paid INR 12,000, filled up the form and I was operated. After the operation, there were lots of medicines and injections, and one injection was like INR 750, and then INR 1500 needed to be paid for the medicine, and everything. That has cost me around INR 25,000–30,000.(Preeti)

The doctor charged INR 50,000 as a deposit, and then 5000 more for a medicine that he prescribed. And now I feel that they only wanted to fetch money from people like us. That’s why he kept my father there for 10 days. Just to make more money. So, yeah, going there was a big mistake.(Rajesh)

From 30,000 rupees, the doctor reduced the price to 12,000 on humanitarian grounds, which is good of him. However, if a horse will do a friendship with the grass, how will he eat? If he shows more humanity to people, how much he will earn? So what is in his hand, he did the best for you but not more.(Preeti)

We changed to government hospital from Sola to VS, but even the problem wasn’t cured, so it’s better to go to the private. Even if it costs more, not an issue, we will go to the private. It’s then that we decided to the Bhavanbai, who diagnosed properly that it was an appendix issue and not a blood clot. So he operated and the appendix was removed.(Preeti)

It’s not the question of the cheaper or higher prices, but when we don’t get attended by the doctor, we don’t get any consultancy or prescription or guidance, so what’s the point going to the CH [civil hospital]. Even if it’s cheaper, it doesn’t make any sense, because they are not suggesting anything, they are not attending the patient.(Chandan)

They knew the DKH is a kidney special hospital and it’s a good hospital, but first, they wanted to have a cheaper option, like CH or some other cheaper hospital, which they can afford. But finally, when they were not satisfied, they didn’t want to risk their father’s treatment and health. So they went to the private, now nothing is more important than their father. Money is not important.(Chandan)

…So she is saying the money is not important for me, my grandson is important for me.(Rupa)

It doesn’t matter actually, the point is, I should recover, I should be treated, the money didn’t make a difference.(Ramesh)

No, she didn’t feel bad because, after seeing the treatment, she thought it’s reasonable that he took 10,000–12,000 INR. This is a must for the treatment. And the doctor is really good, she is still appreciating his treatment. So she has recovered from the pain. She has a great respect for the doctor now. The doctor is really very nice.(Rita)

We paid in two installments because he stayed there for four days, so, on the first day, we paid some of the amounts, and then as the expenses were getting bigger and bigger, we recollected the money from neighbors and relatives, so we paid in two or three installments.(Rupa)

His daughter and his son had a little bit of money. So everyone contributed, from the community, everyone, neighbors, their friends. He wanted to mortgage his house, to save his father’s life, but the community told him not to mortgage the house. They helped him in whatever way they could.(Sweta)

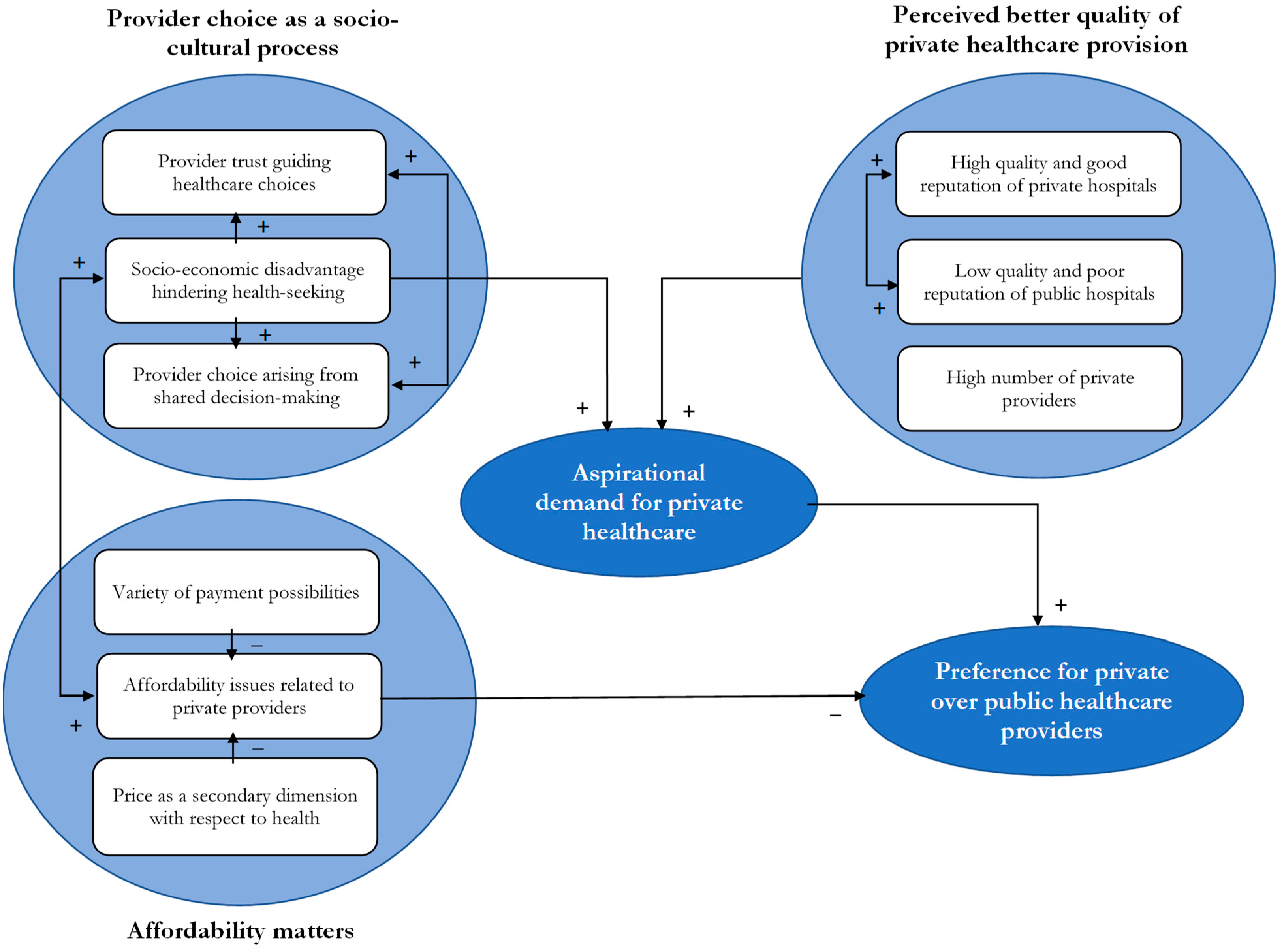

5. Discussion

5.1. Hospital Choice and Its Drivers

5.2. Drivers for Choosing a Private Hospital

5.3. Drivers for Choosing a Public Hospital

5.4. A Grounded Theory Model of Private Healthcare Provider Choice: The Role of Aspirational Demand

6. Contribution, Implications, and Limitations

6.1. Contributions and Implications

6.2. Limitations and Directions for Future Research

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Ethical Considerations

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviation List

| BOP | Bottom of the pyramid |

| IBEF | Indian Brand Equity Foundation |

| IMR | Infant mortality rate |

| IP | Inpatient |

| OP | Outpatient |

| SDG | Sustainable development goal |

| TBL | Triple bottom line |

| TOP | Top of the pyramid |

| U5MR | Under-five mortality rate |

| UNDP | United Nations Development Program |

| WHO | World Health Organization |

References

- Prahalad, C.K. The Fortune at the Bottom of the Pyramid: Eradicating Poverty through Profits; Pearson Prentice Hall: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Prahalad, C.K.; Hart, S.L. The Fortune at the Bottom of the Pyramid. Strategy Mag. 2002, 273, 99–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalid, U.; Seuring, S. Analyzing Base-of-the-Pyramid Research from a (Sustainable) Supply Chain Perspective. Available online: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-017-3474-x (accessed on 10 December 2018).

- Kolk, A.; Rivera-Santos, M.; Rufin, C. Reviewing a Decade of Research on the “Base/Bottom of the Pyramid” (BOP) Concept. Bus. Soc. 2014, 53, 338–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnold, D.G.; Valentin, A. Corporate social responsibility at the base of the pyramid. J. Bus. Res. 2013, 66, 1904–1914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnold, D.G.; Williams, L.H.D. The paradox at the base of the pyramid: Environmental sustainability and market-based poverty alleviation. Int. J. Technol. Manag. 2012, 60, 44–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammond, A.; Kramer, W.J.; Katz, R.S.; Tran, J.T.; Walker, C. The Next 4 Billion: Market Size and Business Strategy at the Base of the Pyramid; World Resources Institute and International Finance Corporation/World Bank Group: Washington, DC, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- George, G.; Howard-Grenville, J.; Joshi, A.; Tihanyi, L. Understanding and tackling societal grand challenges through management research. Acad. Manag. J. 2016, 59, 1880–1895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elkington, J. Cannibals with Forks, the Triple Bottom Line of 21 Century Business; Kluwer Academic Publishers: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Hussain, N.; Rigoni, U.; Orij, R.P. Corporate Governance and Sustainability Performance: Analysis of Triple Bottom Line Performance. J. Bus. Ethics 2018, 149, 411–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Svensson, G.; Høgevold, N.; Ferro, C.; Varela, J.C.; Padin, C.; Wagner, B. A Triple Bottom Line Dominant Logic for Business Sustainability: Framework and Empirical Findings. J. Bus. Bus. Mark. 2016, 23, 153–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reid, D. Sustainable Development: An Introductory Guide; Earthscan: Abingdon-on-Thames, UK, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- WHO. WHO|Poverty and Health; World Health Organ; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- UNDP. Barriers and Opportunities at the Base of the Pyramid—The Role of the Private Sector in Inclusive Development; UDNP: New York, NY, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Wagstaff, A. Poverty and health sector inequalities. Bull. World Health Organ. 2002, 80, 97–105. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Government of India. Draft National Health Policy 2015; Ministry of Health and Family Welfare: New Delhi, India, 2014.

- Bhatnagar, N.; Grover, M. Health care for the “bottom of the pyramid”. Popul. Health Manag. 2014, 17, 5–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yunus, M.; Moingeon, B.; Lehmann-Ortega, L. Building social business models: Lessons from the grameen experience. Long Range Plan. 2010, 43, 308–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, M.; Angeli, F.; Krumeich, A.J.S.M.; Van Schayck, O.C.P. Patterns of illness disclosure among Indian slum dwellers: A qualitative study. BMC Int. Health Hum. Rights 2018, 18, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Das, M.; Angeli, F.; Krumeich, A.J.S.M.; Van Schayck, O.C.P. The gendered experience with respect to health-seeking behaviour in an urban slum of Kolkata, India. Int. J. Equity Health 2018, 17, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Angeli, F.; Jaiswal, A.K. Competitive Dynamics between MNCs and Domestic Companies at the Base of the Pyramid: An Institutional Perspective. Long Range Plan. 2015, 48, 182–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivera-Santos, M.; Rufín, C. Global village vs. small town: Understanding networks at the Base of the Pyramid. Int. Bus. Rev. 2010, 19, 126–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angeli, F.; Jaiswal, A.K. Business Model Innovation for Inclusive Health Care Delivery at the Bottom of the Pyramid. Organ. Environ. 2016, 29, 486–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharyya, O.; Khor, S.; McGahan, A.; Dunne, D.; Daar, A.S.; Singer, P.A. Innovative health service delivery models in low and middle income countries—What can we learn from the private sector? Health Res. Policy Syst. 2010, 8, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marmot, M.; Friel, S.; Bell, R.; Houweling, T.A.; Taylor, S. Closing the gap in a generation: Health equity through action on the social determinants of health. Lancet 2008, 372, 1661–1669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexy, O.; George, G. Category Divergence, Straddling, and Currency: Open Innovation and the Legitimation of Illegitimate Categories. J. Manag. Stud. 2013, 50, 173–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- George, G.; Rao-Nicholson, R.; Corbishley, C.; Bansal, R. Institutional entrepreneurship, governance, and poverty: Insights from emergency medical response servicesin India. Asia Pac. J. Manag. 2015, 32, 39–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Černauskas, V.; Angeli, F.; Jaiswal, A.K.; Pavlova, M. Underlying determinants of health provider choice in urban slums: Results from a discrete choice experiment in Ahmedabad, India. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2018, 18, 473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gangolli, L.V.; Duggal, R.; Shukla, A. Review of Healthcare in India; Centre for Enquiry into Health and Allied Themes: Mumbai, India, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Howard, D.H.; Roy, K. Private Care and Public Health: Do Vaccination and Prenatal Care Rates Differ between Users of Private versus Public Sector Care in India? Health Serv. Res. 2004, 39, 2013–2026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Bank. Landscape of Inclusive Business Models of Healthcare in India Business Model Innovations; The World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- WHO; NHA Indicators. Glob. Health Expend. Database; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- IBEF. Healthcare Industry in India, Indian Healthcare Sector Services; IBEF: New Delhi, India, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Peters, D.H.; Yazbeck, A.S.; Sharma, R.R.; Ramana, G.N.; Pritchett, L.H.; Wagstaff, A. Better Health Systems for India’s Poor; The World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Rangan, V.K.; Thulasiraj, R.D. Making Sight Affordable. Innovations Case Narrative: The Aravind Eye Care System; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Subrahmanyan, S.; Gomez-Arias, J.T. Integrated approach to understanding consumer behavior at bottom of pyramid. J. Consum. Mark. 2008, 25, 402–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahal, A.; Yazbeck, A.S.; Peters, D.H.; Ramana, G.N.V. The Poor and Health Services Use in India; The World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Kuo, T.; Hanafi, J.; Sun, W.; Robielos, R. The Effects of National Cultural Traits on BOP Consumer Behavior. Sustainability 2016, 8, 272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakravarti, D. Voices Unheard: The Psychology of Consumption in Poverty and Development. J. Consum. Psychol. 2006, 16, 363–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chikweche, T.; Stanton, J.; Fletcher, R. Family purchase decision making at the bottom of the pyramid. J. Consum. Mark. 2012, 29, 202–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dawar, N.D.N.; Chattopadhyay, A. Rethinking Marketing Programs for Emerging Markets. Long Range Plan. 2002, 35, 457–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radwan, I. India: Private Health Services for the Poor; The World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Arora, S.; Romijn, H. The empty rhetoric of poverty reduction at the base of the pyramid. Organization 2012, 19, 481–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karnani, A. The Mirage of Marketing to the Bottom of the Pyramid. Calif. Manag. Rev. 2007, 49, 90–111. [Google Scholar]

- Walsh, J.P.; Kress, J.C.; Beyerchen, K.W. Promises and perils at the bottom of the pyramid. Adm. Sci. Q. 2005, 50, 473–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simanis, E.; Hart, S.; Duke, D. The Base of the Pyramid Protocol: Beyond “Basic Needs” Business Strategies. Innov. Technol. Gov. Glob. 2008, 3, 57–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sachs, W. The Development Dictionary: A Guide to Knowledge as Power; Zed Books: London, UK; New York, NY, USA, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Simanis, E.; Hart, S. The Base of the Pyramid Protocol: Toward Next Generation BoP Strategy. Innov. Technol. Gov. Glob. 2008, 2, 1–57. [Google Scholar]

- Sen, A. Development Freedom; Anchor Books: New York, NY, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- India Brand Equity Foundation, Healthcare Industry in India; IBEF: New Delhi, India, 2018.

- World Bank. The World Bank Data: Health; The World Bank Open Data: Washington, DC, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Rao, N. Who Is Paying for India’s Healthcare? Available online: https://thewire.in/health/who-is-paying-for-indias-healthcare (accessed on 10 December 2018).

- National Institute for Transforming India. Health Index, Transforming States to Transform India. Available online: http://social.niti.gov.in/uploads/sample/health_index_report.pdf (accessed on 10 December 2018).

- Kurian, O.C. Gujarat: Economically Upfront, but Far behind in Health. Available online: https://www.orfonline.org/expert-speak/gujarat-economically-upfront-far-behind-health/ (accessed on 10 December 2018).

- Jegede, A. Top 10 Largest Hospitals in the World. Available online: https://www.trendrr.net/3980/best-largest-hospitals-world-cancer-famous-luxurious-expensive/ (accessed on 10 December 2018).

- Government of India. Ninety-Ninth Report, Demands for Grants 2017–2018 (Demand No. 42). Available online: http://164.100.47.5/newcommittee/reports/EnglishCommittees/Committee on Health and Family Welfare/99.pdf (accessed on 10 December 2018).

- Roy, S.; Katoti, R.G.; Tata Services Ltd. Department of Economics and Statistics. In Statistical outline of India, 2006–2007; Tata Services: Mumbai, India, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Government of Gujarat. District wise Government Hospitals. Available online: http://www.magujarat.com/DistrictwiseHospitalEmpanelment.html (accessed on 10 December 2018).

- Polit, D.F.; Beck, C.T. Nursing Research: Generating and Assessing Evidence for Nursing Practice; Lippincott Williams & Wilkins: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Foley, G.; Timonen, V. Using grounded theory method to capture and analyze health care experiences. Health Serv. Res. 2015, 50, 1195–1210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elsey, H.; Manandah, S.; Sah, D.; Khanal, S.; MacGuire, F.; King, R.; Wallace, H.; Baral, S.C. Public health risks in urban slums: Findings of the qualitative “healthy kitchens healthy cities” study in Kathmandu, Nepal. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0163798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beech, R.; Henderson, C.; Ashby, S.; Dickinson, A.; Sheaff, R.; Windle, K.; Wistow, G.; Knapp, M. Does integrated governance lead to integrated patient care? Findings from the innovation forum. Health Soc. Care Commun. 2013, 21, 598–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bain, N.S. Treating patients with colorectal cancer in rural and urban areas: A qualitative study of the patients’ perspective. Fam. Pract. 2000, 17, 475–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Flink, M.; Öhlén, G.; Hansagi, H.; Barach, P.; Olsson, M. Beliefs and experiences can influence patient participation in handover between primary and secondary care—A qualitative study of patient perspectives. BMJ Qual. Saf. 2012, 21 (Suppl. 1), 76–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goudet, S.M.; Kimani-Murage, E.W.; Wekesah, F.; Wanjohi, M.; Griffiths, P.L.; Bogin, B.; Madise, N.J. How does poverty affect children’s nutritional status in Nairobi slums? A qualitative study of the root causes of undernutrition. Public Health Nutr. 2017, 20, 609–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clarke, V.; Braun, V. Teaching thematic analysis: Over- coming challenges and developing strategies for effective learning. Psychologist 2013, 26, 120–123. [Google Scholar]

- Ritchie, J.; Lewis, J.; McNaughton Nicholls, C.; Ormston, R. Qualitative Research Practice: A Guide for Social Science Students and Researchers; SAGE: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Gioia, D.A.; Corley, K.G.; Hamilton, A.L. Seeking Qualitative Rigor in Inductive Research: Notes on the Gioia Methodology. Organ. Res. Methods 2013, 16, 15–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corbin, J.M.; Strauss, A. Grounded theory research: Procedures, canons, and evaluative criteria. Qual. Sociol. 1990, 13, 3–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strauss, A.L.; Corbin, J.M. Basics of Qualitative Research: Techniques and Procedures for Developing Grounded Theory; SAGE: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Gruiskens, J.; Ormiston, J.; Angeli, F.; Van Schayck, O.C. The antecedents of healthcare social entrepreneurship. In Healthcare Entrepreneurship; Wilden, R., Garbuio, M., Angeli, F., Mascia, D., Eds.; Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group: Abingdon, UK, 2018; pp. 221–258. [Google Scholar]

- Burns, D.J. Husband-wife innovative consumer decision making: Exploring the effect of family power. Psychol. Mark. 1992, 9, 175–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lackman, C.; Lanasa, J.M. Family decision-making theory: An overview and assessment. Psychol. Mark. 1993, 10, 81–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, C.; Fern, E.F.; Ye, K. A Temporal Dynamic Model of Spousal Family Purchase-Decision Behavior. J. Mark. Res. 2003, 40, 268–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klein, T. Why do India’s Urban Poor Choose to Go Private? Health Policy Simulations in Slums of Hyderabad; Ibidem-Verl: Stuttgart, Germany, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Sengupta, A.; Nundy, S. The private health sector in India. BMJ 2005, 331, 1157–1158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Das, J.; Hammer, J. Money for nothing: The dire straits of medical practice in Delhi, India. J. Dev. Econ. 2007, 83, 1–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trocchia, P.J.; Saine, R.Q.; Luckett, M.G. I’ve wanted a BMW since I was a kid: An exploratory analysis of the aspirational brand. J. Appl. Bus. Res. 2015, 31, 331–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capaldo, A.; Della Piana, B.; Vecchi, A. Managing Across Cultures in a Globalized World. Findings from a Systematic Literature Review. Glob. Commun. 2012, 1, 7–40. [Google Scholar]

- Jaiswal, A.K. The Fortune at the Bottom or the Middle of the Pyramid? Innov. Technol. Gov. Glob. 2008, 3, 85–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rangan, K.V.; Chu, M.; Petkoski, D. Segmenting the Base of the Pyramid. Harv. Bus. Rev. 2011, 89, 113–117. [Google Scholar]

- Economic Times India. Ayushman Bharat Health Insurance Scheme: Who All It covers and How|Ayushman Bharat Scheme Complete Guide. Available online: https://economictimes.indiatimes.com/wealth/insure/ayushman-bharat-how-to-check-entitlement-and-eligibility/articleshow/65422257.cms (accessed on 10 December 2018).

- Capaldo, A. Network governance: A cross-level study of social mechanisms, knowledge benefits, and strategic outcomes in joint-design alliances. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2014, 43, 685–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capaldo, A. Network structure and innovation: The leveraging of a dual network as a distinctive relational capability. Strategy Manag. J. 2007, 28, 585–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capaldo, A.; Giannoccaro, I. How does trust affect performance in the supply chain? the moderating role of interdependence. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2015, 166, 36–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Factors | Implication | Sources |

|---|---|---|

| Strong social bonds | Trust relationships are key | [1,38] |

| Illiteracy, education, information, socioeconomic conditions | Hinder making rational/well-informed choice decisions | [1,39] |

| Transportation | Buy locally | [1,41,42] |

| Long working hours | Need for different opening hours | [1] |

| Income level | Buy small quantities | [1,41] |

| Income instability | Buying decisions cannot be deferred | [1] |

| Family makeup | Purchase decisions depend on what role family members take | [40] |

| Individual roles | ||

| Gender | ||

| Other family members |

| Indicator (Year) | India | Gujarat | World |

|---|---|---|---|

| Maternal mortality ratio, per 100,000 live births (2011–2013) | 167 | 112 | 226 |

| Infant mortality rate, per 1000 live births (2015) | 37 | 33 | 31.2 |

| Under-5 mortality rate, per 1000 live births (2014) | 45 | 41 | 43.5 |

| Total fertility rate (2014) | 2.3 | 2.3 | 2.4 |

| Hospital | Private/Public | MA Yojana | Number of Beds | Number of Inpatient Registrations (IP) * | Number of Outpatient Registrations (OP) * |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Anonymous | Private | Yes | 290 | 213 | / |

| 2. Civil | Public | Yes | 2000 | 1883 | 9987 |

| 3. HCG | Private | Yes | 110 | 137 | 222 |

| 4. Shardabhen | Public | Yes | 350 | 642 | / |

| 5 Jivraj Mehta | Private trust | No | 100–200 | 165 | 2779 |

| 6. Shalby | Private | No | 1700 | 165 | 1927 |

| Area | Slums | Chawls | Total Housing Stock |

|---|---|---|---|

| Wadaj | 42.32% | 7.65% | 21.633 |

| Kalupur (north and south) | 0.29% | 0% | 7.225 |

| Dariapur | 0% | 0% | 4.084 |

| # | Pseudonym | Age | Gender | Education | Employment | Household Income (INR/Month) | Members in Household | Residential Area | Cost of Treatment (INR) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Kriti | 50 | F | None | Security (H) | 8000–10,000 | 7 | Wadaj | 500 |

| 2 | Shanti | 43 | F | 5th grade | Carpenter (H) | 8000–10,000 | 7 | Wadaj | 500 |

| 3 | Meeta | 40 | F | None | Pani puri (H) | 8000–10,000 | 6 | Wadaj | 8.000 |

| 4 | Chandan | 40 | M | 10th grade | Carpenter | 8000–10,000 | 9 | Wadaj | 16,000 (monthly) |

| 5 | Akshay | 36 | M | None | Statue-maker | <4000 | 5 | Nehrunagar | ~0–10 |

| 6 | Abhijit | 40 | M | None | Peddle | <4000 | 6 | Nehrunagar | ~0–10 |

| 7 | Preeti | 40 | F | None | Garbage collector | 8000–10,000 | 8 | Nehrunagar | 30,000 |

| 8 | Raj | 46 | M | 6th grade | Driver | 20,000–25,000 | 4 25 (joint) | Ambawadi | |

| 9 | Ramesh | 35 | M | Senior 2nd grade | Worker | 10,000–12,000 | 4 | Shahibag | 5000 |

| 10 | Soni | 40 | M | None | Worker | 6000–8000 | 4 | Shahibag | ~0–10 |

| 11 | Sweta | 40 | F | None | Worker | <4000 | 6 | Shahibag | ~0–10 |

| 12 | Suhash | 33 | M | 5th | Bamboo curtains | 10,000–12,000 | 5 | Isanpur | 3500 |

| 13 | Rita | 60 | F | None | Statue-maker | <4000 | 1 | Navrangpura | 12,000 |

| 14 | Priyanka | 20 | F | None | Trading statues | 15,000 | 10 | Gulabhai Tekra | 16,500 |

| 15 | Meena | 45 | F | None | Statue-maker | 15,000–20,000 | 5 | Gulabhai Tekra | 95,000 |

| 16 | Rajesh | 36 | M | 10th grade | Water-boring | 8000–10,000 | 5 | Vishala | 82,000 |

| 17 | Rupa | 58 | F | 7th grade | None | 10,000–12,000 | 11 | Vasna | 30,000 |

| 18 | Jayanti | 46 | F | None | None | 4000–6.000 | 6 | Vasna | 300,000 |

| 19 | Ram | 25 | M | None | Worker | 8000–10,000 | 5 | Vastrapur | 2000 |

| 20 | Baldev | 40 | M | 10th grade | Worker | 8000–10,000 | 3 | Vastrapur | ~0–10 |

| 21 | Jamuna | 51 | F | 5th grade | None | None | 3 | Khanpur | ~0–10 |

| Income Group | BOP | TOP | Total | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hospital Type | |||||

| Private | Count | 10 | 26 | 36 | |

| Expected count | 20.3 | 15.7 | 36 | ||

| % within hospital type | 27.8% | 72.2% | 100.0% | ||

| % within income group | 4.1% | 13.7% | 8.3% | ||

| % of total | 2.3% | 6.0% | 8.3% | ||

| Public | Count | 236 | 164 | 400 | |

| Expected count | 225.7 | 174.3 | 400 | ||

| % within hospital type | 59.0% | 41.0% | 100.0% | ||

| % within income group | 95.9% | 86.3% | 91.7% | ||

| % of total | 54.1% | 37.6% | 91.7% | ||

| Total | Count | 246 | 190 | 436 | |

| Expected count | 246 | 190 | 436 | ||

| % within hospital type | 56.4% | 43.6% | 100.0% | ||

| % within income group | 100.0% | 100.0% | 100.0% | ||

| % of total | 56.4% | 43.6% | 100.0% | ||

| Income Group | BOP | TOP | Total | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Type of Visit | |||||

| Unknown | Count | 0 | 1 | 1 | |

| Expected count | 0.6 | 0.4 | 1 | ||

| % within type of visit | 0.0% | 100.0% | 100.0% | ||

| % within income group | 0.0% | 0.5% | 0.2% | ||

| % of total | 0.0% | 0.2% | 0.2% | ||

| IP | Count | 34 | 19 | 53 | |

| Expected count | 30.3 | 22.7 | 53 | ||

| % within type of visit | 64.2% | 35.8% | 100.0% | ||

| % within income group | 13.8% | 10.3% | 12.3% | ||

| % of total | 7.9% | 4.2% | 12.1% | ||

| OP | Count | 212 | 165 | 377 | |

| Expected count | 215.2 | 161.8 | 377 | ||

| % within type of visit | 56.2% | 43.8% | 100.0% | ||

| % within income group | 86.2% | 89.2% | 87.5% | ||

| % of total | 49.2% | 38.3% | 87.5% | ||

| Total | Count | 246 | 184 | 430 | |

| Expected count | 246 | 184 | 430 | ||

| % within type of visit | 57.2% | 42.8% | 100.0% | ||

| % within income group | 100.0% | 100.0% | 100.0% | ||

| % of total | 57.2% | 42.8% | 100.0% | ||

© 2018 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Angeli, F.; Ishwardat, S.T.; Jaiswal, A.K.; Capaldo, A. Socio-Cultural Sustainability of Private Healthcare Providers in an Indian Slum Setting: A Bottom-of-the-Pyramid Perspective. Sustainability 2018, 10, 4702. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10124702

Angeli F, Ishwardat ST, Jaiswal AK, Capaldo A. Socio-Cultural Sustainability of Private Healthcare Providers in an Indian Slum Setting: A Bottom-of-the-Pyramid Perspective. Sustainability. 2018; 10(12):4702. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10124702

Chicago/Turabian StyleAngeli, Federica, Shila Teresa Ishwardat, Anand Kumar Jaiswal, and Antonio Capaldo. 2018. "Socio-Cultural Sustainability of Private Healthcare Providers in an Indian Slum Setting: A Bottom-of-the-Pyramid Perspective" Sustainability 10, no. 12: 4702. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10124702

APA StyleAngeli, F., Ishwardat, S. T., Jaiswal, A. K., & Capaldo, A. (2018). Socio-Cultural Sustainability of Private Healthcare Providers in an Indian Slum Setting: A Bottom-of-the-Pyramid Perspective. Sustainability, 10(12), 4702. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10124702