The Impact of Consumers’ Attitudes toward a Theme Park: A Focus on Disneyland in the Los Angeles Metropolitan Area

Abstract

:1. Introduction

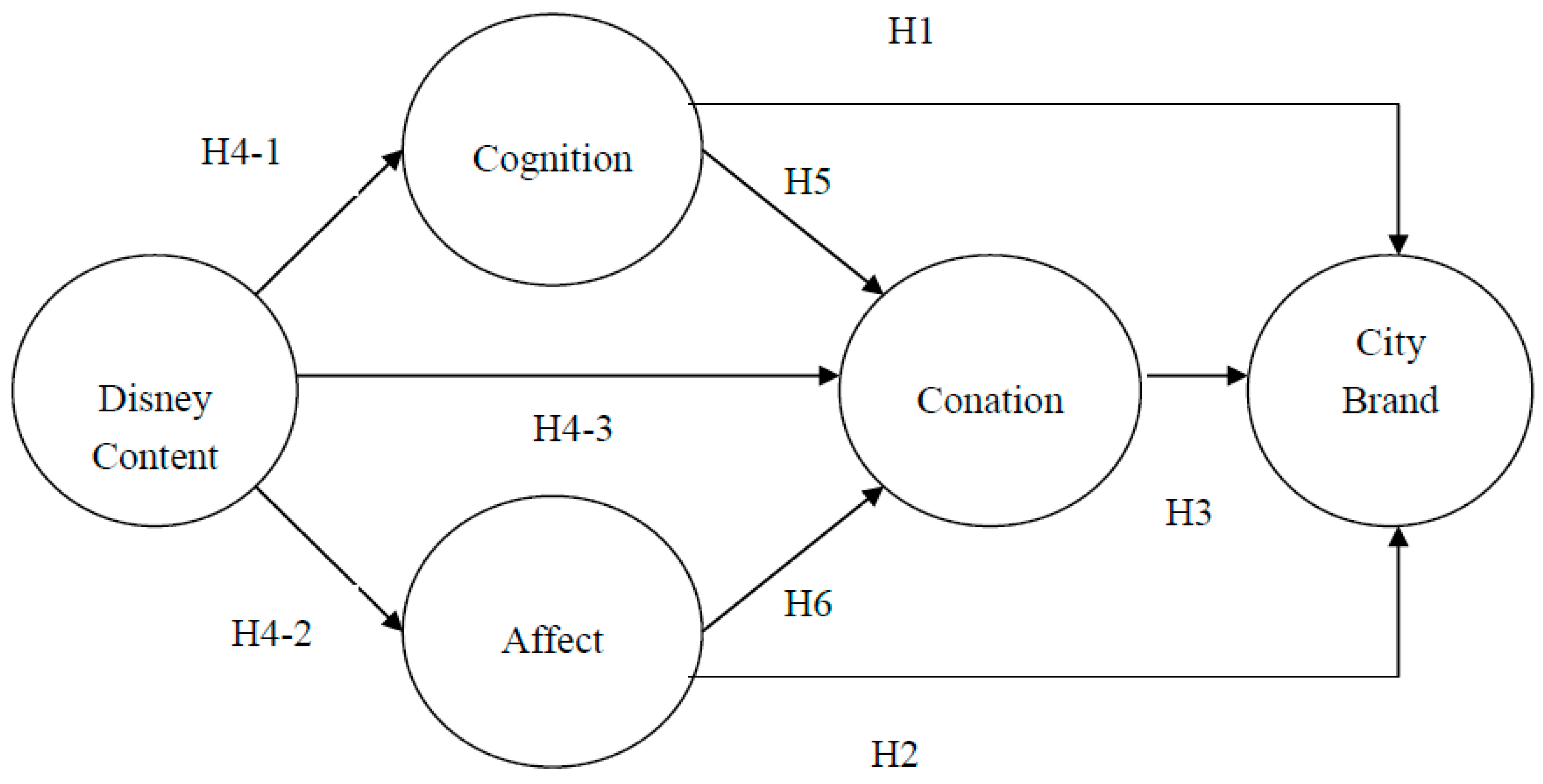

2. Conceptual Framework

2.1. Theme Parks

2.2. City Branding

2.3. Tripartite Model of Attitudes

3. Methodology

3.1. Data Collection

3.2. Sample

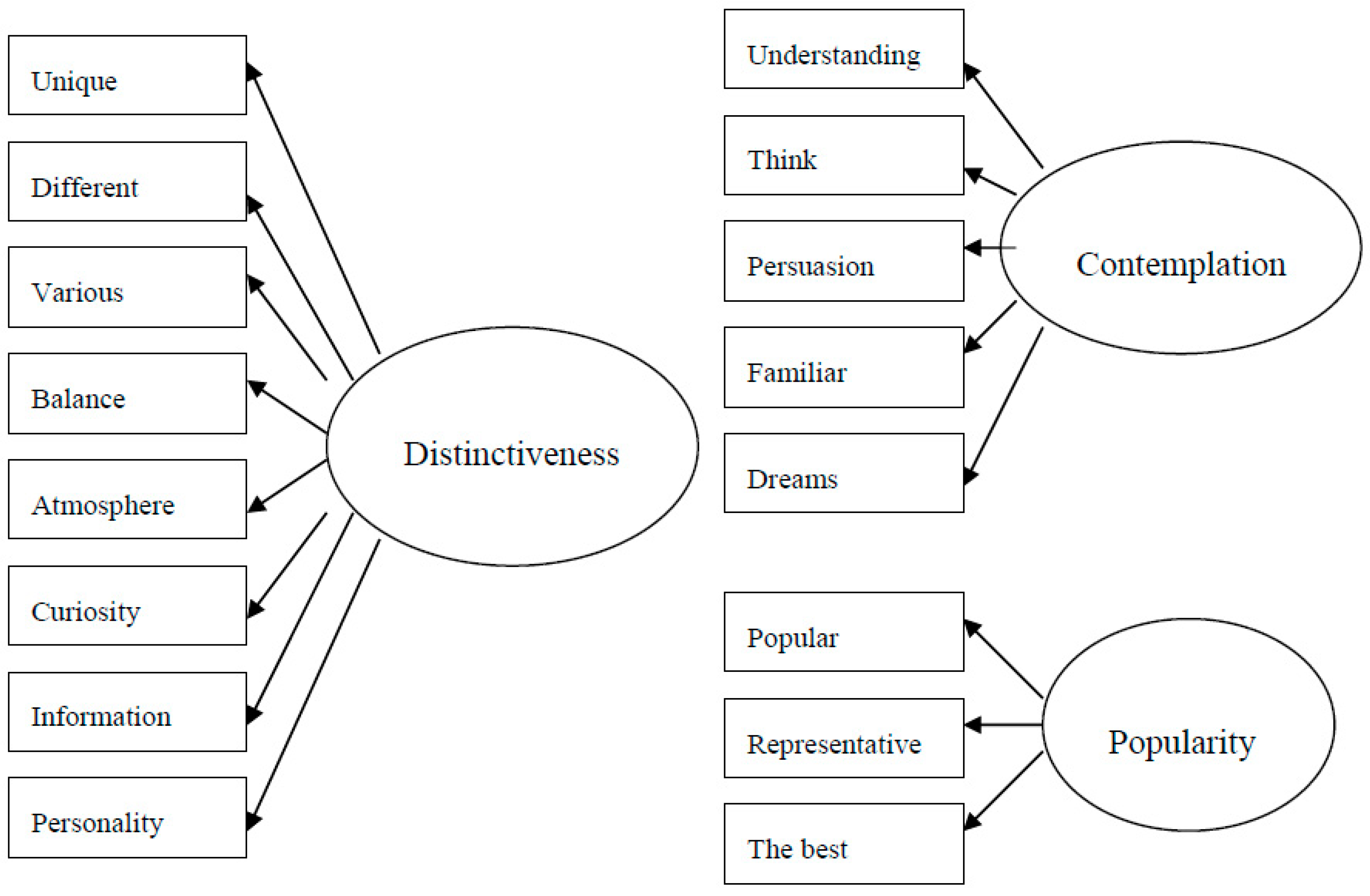

3.3. Measurement

4. Research Findings

4.1. Exploratory Factor Analysis

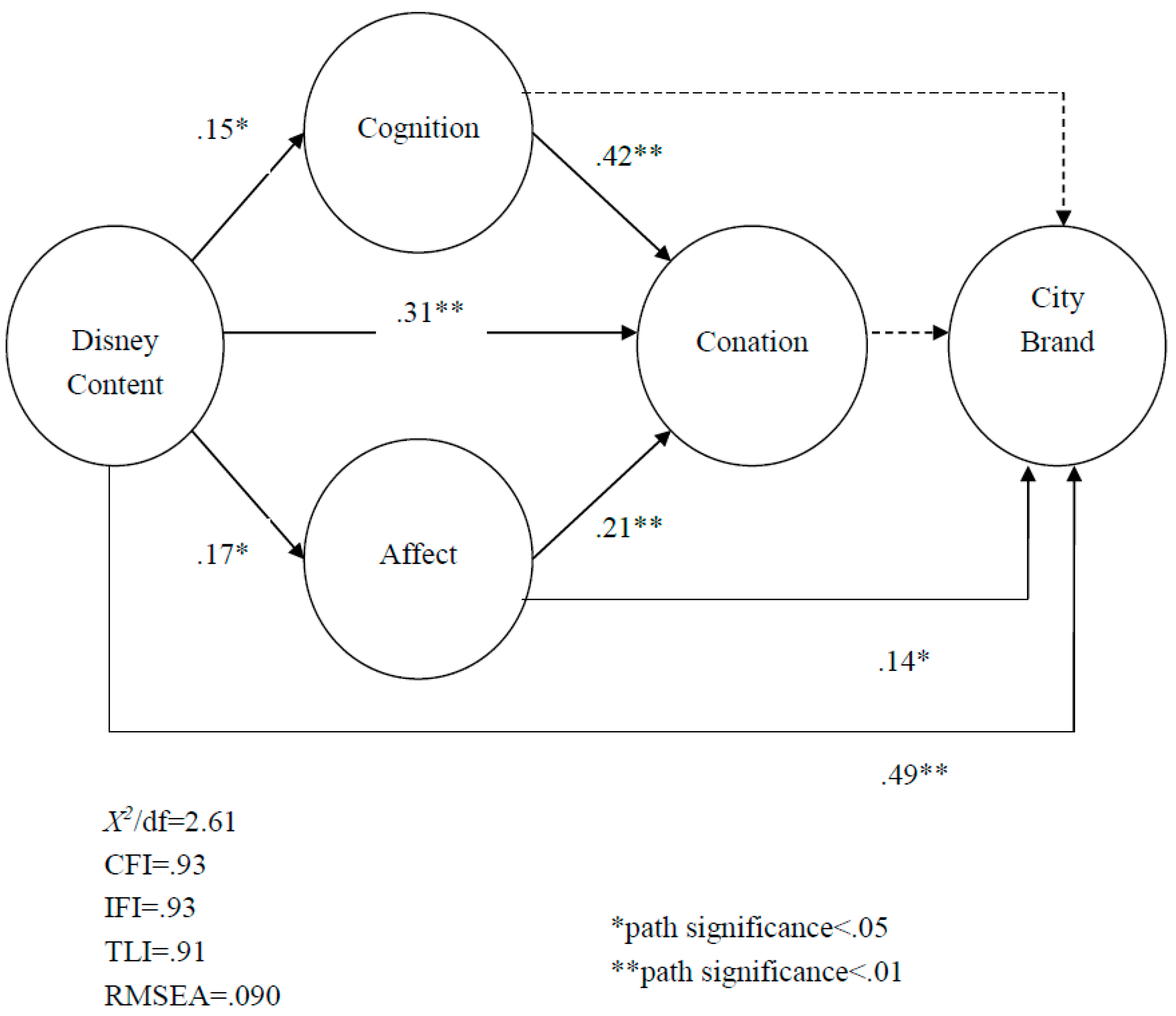

4.2. Model Testing

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Warnaby, G.; Ashworth, G.J.; Kavaratzis, M. Sketching futures for place branding. In Rethinking Place Branding; Kavaratzis, M., Warnaby, G., Ashworth, G.J., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2015; pp. 241–248. [Google Scholar]

- Braun, E.; Kavaratzis, M.; Zenker, S. My city–my brand: The role of residents in place branding. J. Place Manag. Dev. 2013, 61, 18–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotler, P.; Gertner, D. Country as brand, product, and beyond: A place marketing and brand management perspective. J. Brand Manag. 2002, 9, 249–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papadopoulos, N. Place branding: Evolution, meaning and implications. Place Brand. 2004, 1, 36–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Fabio, A. The psychology of sustainability and sustainable development for well-being in organizations. Front. Psychol. 2017, 8, 1534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Di Fabio, A. Positive Healthy Organizations: Promoting well-being, meaningfulness, and sustainability in organizations. Front. Psychol. 2017, 8, 1938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Di Fabio, A.; Bucci, O. Green positive guidance and green positive life counseling for decent work and decent lives: Some empirical results. Front. Psychol. 2016, 7, 261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anholt, S. The Anholt-GMI city brands index: How the world sees the world’s cities. Place Brand. 2006, 2, 18–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, B. Destination Branding for Small Cities, 2nd ed.; Creative Leap Books: Tualatin, OR, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Hultman, M.; Yeboah-Banin, A.A.; Formaniuk, L. Demand- and supply-side perspectives of city branding: A qualitative investigation. J. Bus. Res. 2016, 69, 5153–5157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kavaratzis, M. From city marketing to city branding: Toward a theoretical framework for developing city brands. Place Brand 2004, 1, 58–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucarelli, A.; Berg, P. City branding: A state-of-the-art of the research domain. J. Place Manag. Dev. 2011, 4, 9–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merrilees, B.; Miller, D.; Herington, C. City branding: A facilitating framework for stressed satellite cities. J. Bus. Res. 2013, 66, 37–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moilanen, T. Challenges of city branding: A comparative study of 10 European cities. Place Brand. Public Dipl. 2015, 11, 216–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papadopoulos, N.; Heslop, L. Country equity and country branding: Problem and prospects. J. Brand Manag. 2002, 9, 294–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warnaby, G.; Davies, B. Commentary: Cities as service factories? Using the servuction system for marketing cities as shopping destinations. Int. J. Retail Distrib. Manag. 1997, 25, 204–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanna, S.; Rowley, J. An Analysis of terminology use in place branding. Place Brand. Public Dipl. 2008, 4, 61–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsueh, Y.-H.; Chang, C.-C. Promoting city branding by defining the tourism potential area based on GIS mapping. In Strategy Place Branding Method Theory Tourism Attraction; Bayraktar, A., Uslay, C., Eds.; IGI Global: Hershey, PA, USA, 2017; pp. 140–156. [Google Scholar]

- Roult, R.; Adjizian, J.-M.; Auger, D. Tourism conversion and place branding: The case of the Olympic Park in Montreal. Int. J. Tour. Cities 2016, 2, 77–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Q.; Du, R.; Ma, Y. Factors influencing theme park visitor brand-switching behavior as based on visitor perception. Curr. Issues Tour. 2016, 19, 1425–1446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubin, J. Themed Entertainment Association/Economics Research Associates Attraction Attendance Report, 2009. Available online: www.themeit.com/TEAERA2008.pdf (accessed on 3 May 2016).

- World Tourism Organization. 2009. Available online: http://www.world-tourism.org (accessed on 4 May 2016).

- Clave, S.A. The Global Theme Park Industry; CABI: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Bennett, T. The Birth of the Museum; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Davis, S.G. The theme park: Global industry and cultural form. Media Cult. Soc. 1996, 18, 399–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stylidis, D.; Cherifi, B. Characteristics of destination image: Visitors and non-visitors’ images of London. Tour. Rev. 2018, 73, 55–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, D. The Quotable Walt Disney Compiled; Disney Editions: New York, NY, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Milman, A. The global theme park industry. Worldw. Hosp. Tour. Themes 2010, 2, 220–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mills, S.F. Disney and the promotions of synthetic worlds. Am. Stud. Int. 1990, 28, 66–80. [Google Scholar]

- Milman, A. Evaluating the guest experience at theme parks: An empirical investigation of key attributes. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2010, 11, 373–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kemperman, A.; Borgers, A.; Oppewal, H.; Timmermans, H. Predicting the duration of theme park visitors’ activities: An ordered logit model using conjoint choice data. J. Travel Res. 2003, 41, 375–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milman, A. The future of the theme park and attraction industry: A management perspective. J. Travel Res. 2001, 40, 139–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geissler, G.; Rucks, C. The overall theme park experience: A visitor satisfaction tracking study. J. Vacat. Mark. 2011, 17, 127–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milman, A. Market identification of a new theme park: An example from central Florida. J. Travel Res. 1998, 26, 7–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapferer, J. Strategic Brand Management: New Approaches to Creating and Evaluating Brand Equity; Kogan Page: London, UK, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Hankinson, G. The brand image of tourism destinations: A study of the saliency of organic images. J. Prod. Bran. Manag. 2004, 13, 6–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dinnie, K. Place branding: Overview of an emerging literature. Place Brand. 2004, 1, 106–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, Y. Branding the nation: What is being branded. J. Vacat. Mark. 2006, 12, 5–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kavaratzis, M.; Ashworth, G.J. City Branding: An effective assertion of identity or a transitory marketing trick? J. Econ. Soc. Geogr. 2005, 96, 506–514. [Google Scholar]

- Buhalis, D. Marketing the competitive destination of the future. Tour. Manag. 2000, 21, 97–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kaplan, M.; Yurt, O.; Guneri, B.; Kurtulus, K. Branding places: Applying brand personality concept to cities. Euro. J. Mark. 2010, 44, 1286–1304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Westerbeek, H.; Turner, P.; Ingerson, L. Key success factors in bidding for hallmark sporting events. Int. Mark. Rev. 2002, 19, 303–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapareliotis, I.; Panopoulos, A.; Panigyrakis, G. The Influence of the Olympic games on Beijing consumers’ perceptions of their city tourism development. Asia Pac. J. Mark. Logist. 2010, 22, 90–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eagly, A.; Chaiken, S. The Psychology of Attitudes; Harcourt Brace Jovanovich: Fort Worth, TX, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Nijssen, E.; Douglas, S. Consumer world-mindedness and attitudes toward product positioning in advertising: An examination of global versus foreign versus local position. J. Int. Mark. 2011, 19, 113–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Youn, S.; Kim, H. Antecedents of consumer attitudes toward cause-related marketing. J. Adv. Res. 2008, 48, 123–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fabrigar, L.; MacDonald, T.; Wegener, D. The structure of attitudes. In Handbook of Attitudes; Albarracin, D., Johnson, B.T., Zanna, M.P., Eds.; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates: Mahwah, NJ, USA, 2005; pp. 79–124. [Google Scholar]

- Detenber, B.H.; Simons, R.F.; Bennett, G.G. Roll ‘em!: The effects of picture motion on emotional responses. J. Broadcast. Electron. Med. 1998, 42, 113–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kipper, P. Television camera movement as a source of perceptual information. J. Broadcast. Electron. Media 1986, 30, 295–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breckler, S.J. Empirical validation of affect, behavior, and cognition as distinct components of attitude. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1984, 47, 1191–1205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krech, D.; Crutchfield, R.S. Theory of Probability for Social Psychology; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 1948. [Google Scholar]

- Vaughn, R. How advertising works: A planning model. J. Adv. Res. 1980, 20, 27–33. [Google Scholar]

- Oliver, R.L. Satisfaction: A Behavioral Perspective on the Consumer; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Back, K.-J.; Parks, S. A brand loyalty model involving cognitive, affective, and conative brand loyalty and customer satisfaction. J. Hosp. Tour. Res. 2003, 27, 419–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zajonc, R.B.; Markus, H. Affective and cognitive factors in preferences. J. Consum. Res. 1982, 9, 123–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burke, M.C.; Edell, J.A. The impact of feelings on ad-based affect and cognition. J. Mark. Res. 1989, 26, 69–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holbrook, M.B.; Batra, R. Assessing the role of emotions as mediators of consumer responses to advertising. J. Consum. Res. 1987, 14, 404–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morris, J.D. Observations: SAM: The self-assessment manikin; an efficient cross-cultural measurement of emotional response. J. Adv. Res. 1995, 35, 63–68. [Google Scholar]

- Morris, J.D.; Woo, C.M.; Cho, C.-H. Internet measures of advertising effects: A global issue. J. Curr. Issues Res. Adv. 2003, 25, 25–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osgood, C.E.; Suci, G.J.; Tannenbaum, P.H. The Measurement of Meaning; University of Illinois Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 1957. [Google Scholar]

- Mehrabian, A.; Russell, J.A. An Approach to Environmental Psychology; M.I.T. Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1974. [Google Scholar]

- Speed, R.; Thompson, P. Determinants of sports sponsorship response. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2000, 28, 226–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jun, J.; Cho, C.-H.; Kwon, H. The role of affect and cognition in consumer evaluations of corporate visual identity: Perspectives from the United States and Korea. J. Bran. Manag. 2008, 15, 382–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wakefield, K.; Bennett, G. Affective intensity and sponsor identification. J. Adv. 2010, 39, 99–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bigne, J.; Mattila, A.; Andreu, L. The impact of experiential consumption cognitions and emotions on behavioral intentions. J. Serv. Mark. 2008, 22, 303–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jun, J.; Lee, H.; Park, J. Roles of media exposure and interpersonal experiences on country brand: The mediated risk perception model. J. Promot. Manag. 2009, 15, 321–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Appadurai, A. Disjuncture and difference in the global cultural economy. Public Cult. 1990, 2, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kruglanski, A.; Stroebe, W. The Influence of beliefs and goals on attitudes; issues of structure, function, and dynamics. In The Handbook of Attitudes; Albarracin, D., Johnson, B.T., Zanna, M.P., Eds.; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates: Mahwah, NJ, USA, 2005; pp. 323–368. [Google Scholar]

- Clore, G.; Schnall, S. The Influence of affect on attitude. In The Handbook of Attitudes; Albarracin, D., Johnson, B.T., Zanna, M.P., Eds.; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates: Mahwah, NJ, USA, 2005; pp. 437–489. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, C.-H.; Morais, D.; Kerstetter, D.; Hou, J.-S. Examining the role of cognitive and affective image in predicting choice across natural, developed, and theme-park destination. J. Travel Res. 2007, 46, 183–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donovan, R.; Rossiter, J. Store atmosphere: An environmental psychology approach. J. Retail. 1982, 58, 57–71. [Google Scholar]

- Kock, N.; Moqbei, M. Statistical power with respect to true sample and true population paths: A PLS-based SEM illustration. Int. J. Data Anal. Tech. Strateg. 2014, 8, 316–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Havlena, W.; Holbrook, M. The varieties of consumption experience: Comparing two typologies of emotion in consumer behavior. J. Consum. Res. 1986, 13, 394–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goossens, C. Tourism information and pleasure motivation. Ann. Tour. Res. 2000, 27, 301–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variables | Dimensions or Indicators | M | SD | CFA Loadings |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Disney Content | To me, Disney content is: | |||

| Unfavorable/Favorable | 5.60 | 1.23 | 0.86 | |

| Bad/Good | 5.42 | 1.39 | 0.95 | |

| Unlikable/Likable | 5.45 | 1.42 | 0.92 | |

| Negative/Positive | 5.42 | 1.41 | 0.91 | |

| Index | 5.47 | 1.27 | α = 0.95 | |

| Cognition | Distinctiveness | 4.67 | 1.33 | 0.93 |

| Contemplation | 3.42 | 1.35 | 0.48 | |

| Popularity | 4.95 | 1.71 | 0.77 | |

| Index | 4.35 | 1.19 | α = 0.74 | |

| Affect | Pleasure | 3.78 | 1.44 | 0.70 |

| Arousal | 3.34 | 1.33 | 1.02 | |

| Dominance | 2.97 | 1.36 | 0.80 | |

| Index | 3.36 | 1.22 | α = 0.86 | |

| Conation | Information search intentions | 3.85 | 1.70 | 0.70 |

| Recommendation intentions to friends | 5.41 | 1.61 | 0.70 | |

| Purchase intentions of Disney character products | 4.37 | 1.52 | 0.88 | |

| Visit intentions of the LA Disneyland | 3.80 | 1.93 | 0.66 | |

| Index | 4.36 | 1.37 | α = 0.82 | |

| LA Attitudes | To me, LA is: | |||

| Unfavorable/Favorable | 5.19 | 1.28 | 0.88 | |

| Bad/Good | 5.05 | 1.34 | 0.94 | |

| Unlikable/Likable | 5.18 | 1.38 | 0.93 | |

| Negative/Positive | 5.05 | 1.38 | 0.80 | |

| Index | 5.12 | 1.23 | α = 0.94 |

© 2018 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Bae, Y.H.; Moon, S.; Jun, J.W.; Kim, T.; Ju, I. The Impact of Consumers’ Attitudes toward a Theme Park: A Focus on Disneyland in the Los Angeles Metropolitan Area. Sustainability 2018, 10, 3409. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10103409

Bae YH, Moon S, Jun JW, Kim T, Ju I. The Impact of Consumers’ Attitudes toward a Theme Park: A Focus on Disneyland in the Los Angeles Metropolitan Area. Sustainability. 2018; 10(10):3409. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10103409

Chicago/Turabian StyleBae, Young Han, Sangkil Moon, Jong Woo Jun, Taewan Kim, and Ilyoung Ju. 2018. "The Impact of Consumers’ Attitudes toward a Theme Park: A Focus on Disneyland in the Los Angeles Metropolitan Area" Sustainability 10, no. 10: 3409. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10103409

APA StyleBae, Y. H., Moon, S., Jun, J. W., Kim, T., & Ju, I. (2018). The Impact of Consumers’ Attitudes toward a Theme Park: A Focus on Disneyland in the Los Angeles Metropolitan Area. Sustainability, 10(10), 3409. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10103409