The Pyruvate–Glyoxalate Pathway as a Toxicity Assessment Tool of Xenobiotics: Lessons from Prebiotic Chemistry

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Chemicals and Water Extraction

2.2. Pyruvate–Glyoxylate Assay

2.3. Rainbow Trout Acute Lethality Tests

2.4. Data Analysis

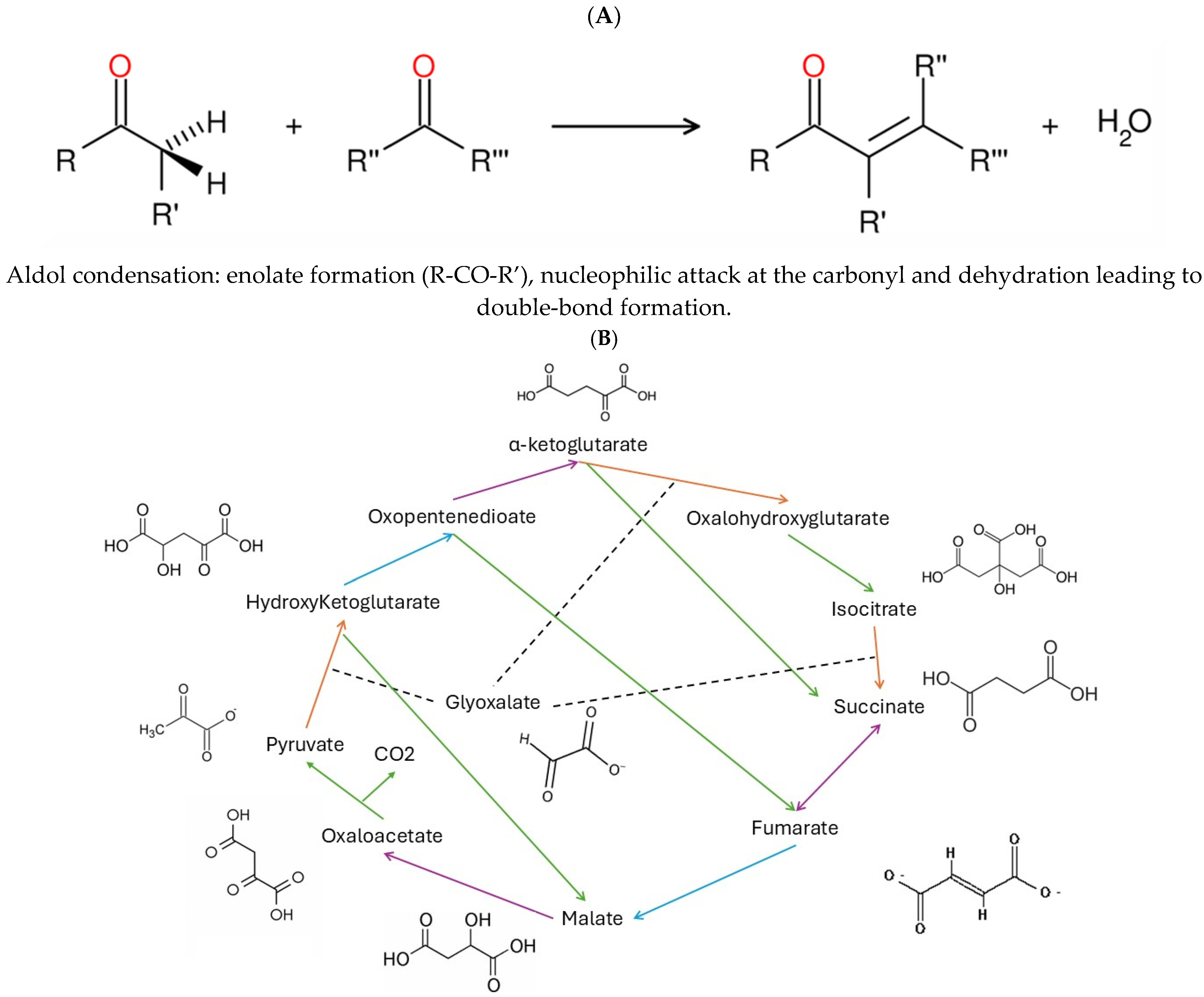

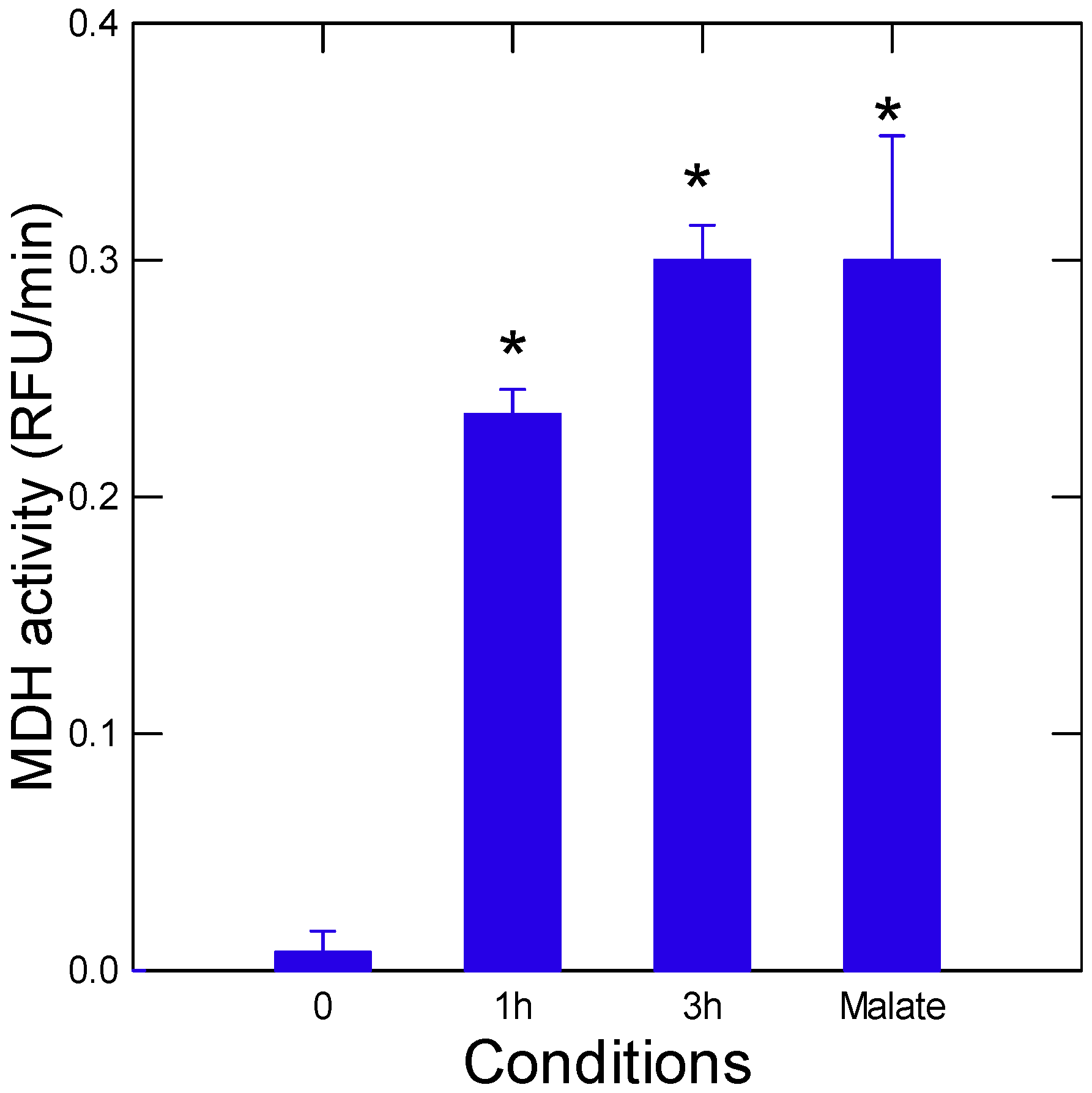

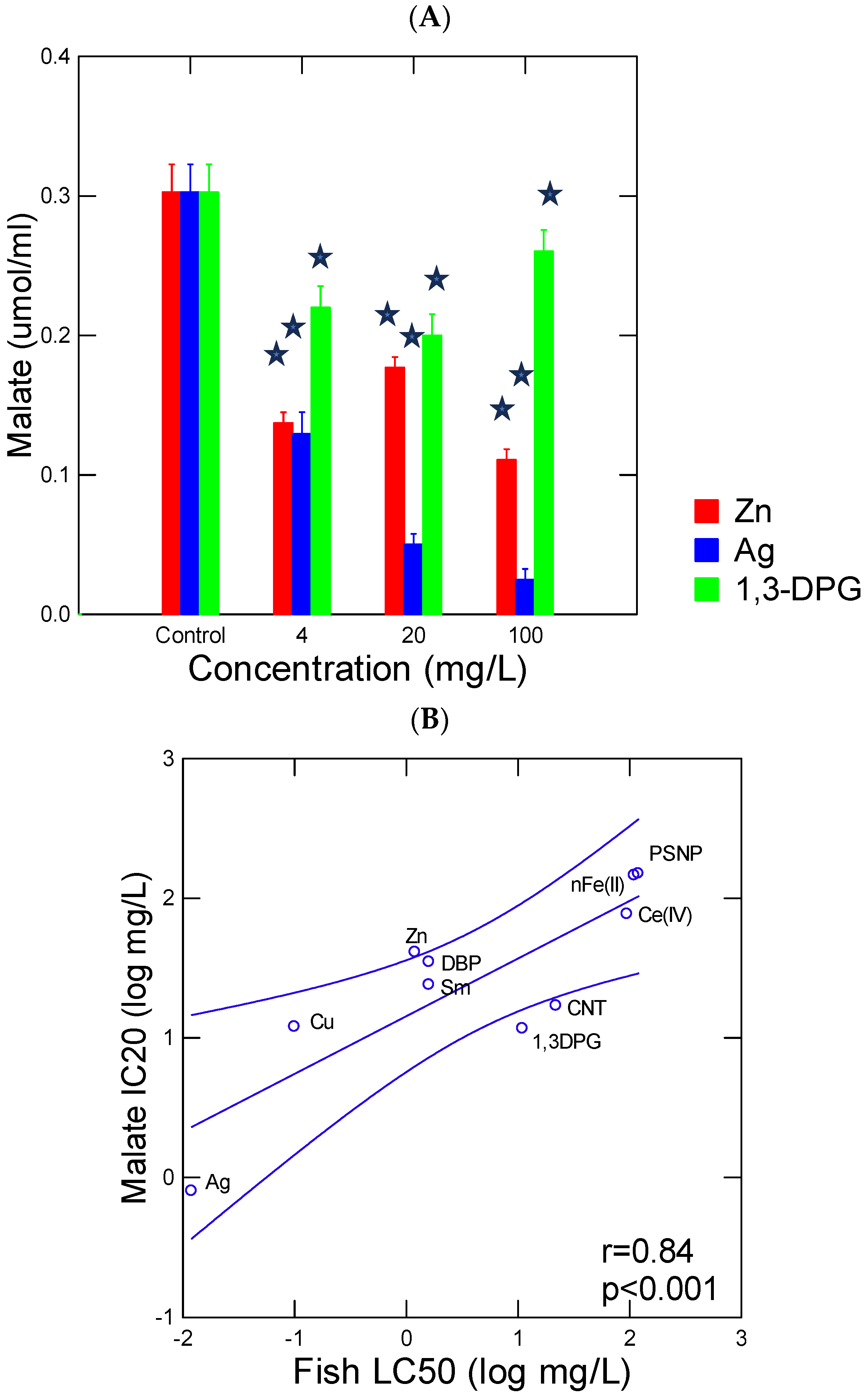

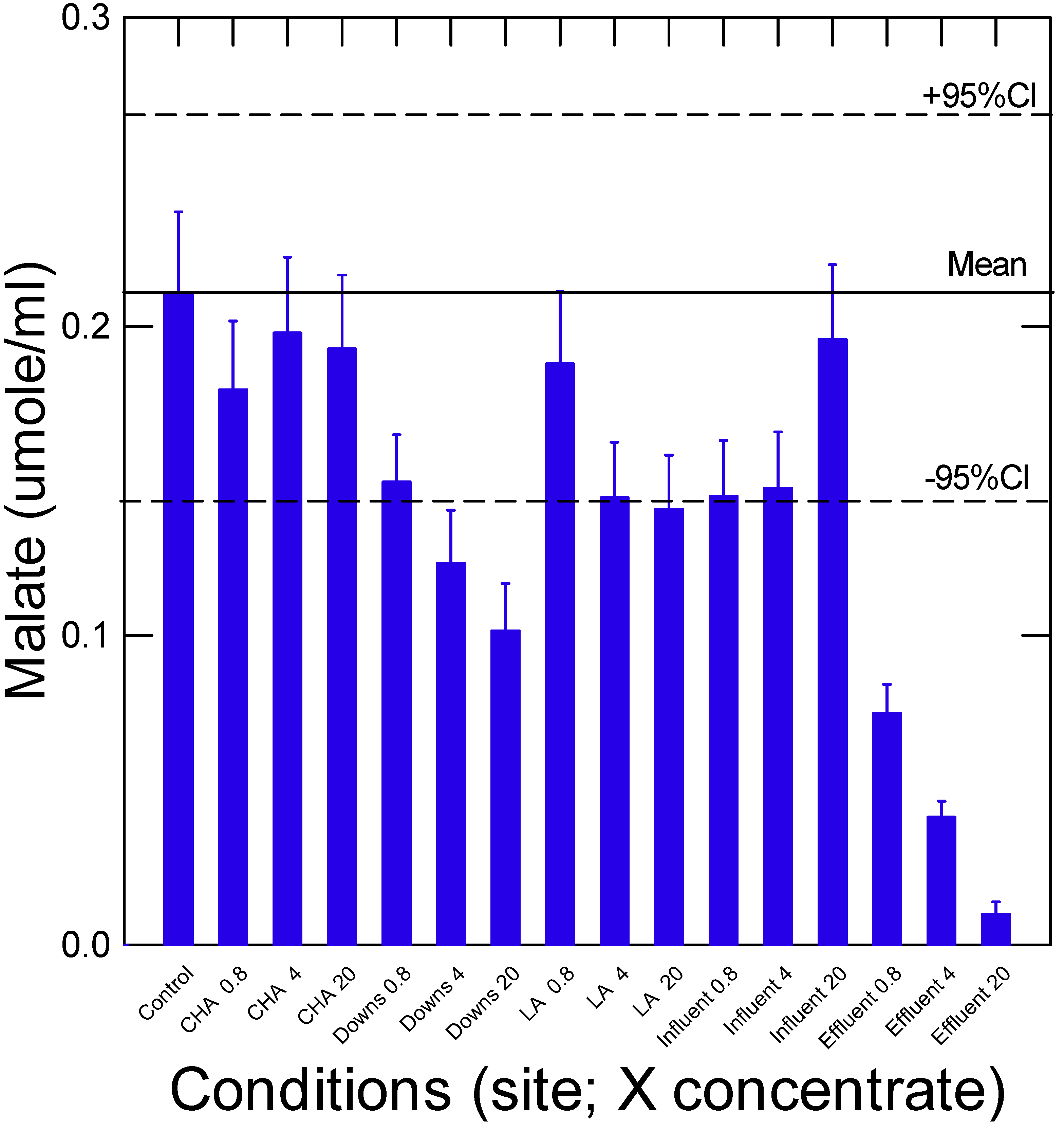

3. Results and Discussion

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ten Brink, B.J.E.; Woudstra, J.H. Towards an effective and rational water management: The aquatic outlook project-integrating water management, monitoring and research. Eur. Water Pollut. Control 1991, 1, 20–27. [Google Scholar]

- Minister of Justice. Fishery Act; R.S., c. F-14, s. 1; Minister of Justice: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 2025; 111p, Available online: https://laws.justice.gc.ca/eng/acts/f-14/index.html (accessed on 1 November 2025).

- Costan, G.; Bermingham, N.; Blaise, C.; Ferard, J.F. Potential ecotoxic effects probe (PEEP): A novel index to assess and compare the toxic potential of industrial effluents. Environ. Toxicol. Water Qual. 1993, 8, 115–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.; Sun, F.; Liao, H.; Guo, Y.; Wang, J.; Wu, F. Quantitative characteristics and multiple probabilistic risk assessment of small-sized microplastics in the middle and lower reaches of the Hanjiang River, China. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2025, 220, 118404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farley, G.; Bouchard, P.; Faille, C.; Trottier, S.; Gagné, F. Towards the standardization of Hydra vulgaris bioassay for toxicity assessments of liquid samples. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2025, 290, 117560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gagné, F.; Roubeau Dumont, E.; Chantale, A. The effects of selected metals and rare earth elements on the peroxidase toxicity assay. Adv. Earth Environ. Sci. 2025, 6, 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Braakman, R.; Smith, E. The compositional and evolutionary logic of metabolism. Phys. Biol. 2013, 10, 011001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nogal, N.; Sanz-Sanchez, M.; Vela-Gallego, S.; Ruiz-Mirazo, K.; de la Escosura, A. The protometabolic nature of prebiotic chemistry. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2023, 52, 7359–7388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, P.Q.; Adam, Z.R.; Fahrenbach, A.C. Prebiotic Reaction Networks in Water. Life 2020, 10, 352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muchowska, K.B.; Varma, S.J.; Moran, J. Synthesis and breakdown of universal metabolic precursors promoted by Iron. Nature 2019, 569, 104–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Varma, S.J.; Muchowska, K.B.; Chatelain, P.; Moran, J. Native iron reduces CO2 to intermediates and end-Products of the acetyl-CoA Pathway. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 2018, 2, 1019–1024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Emsley, J. The Elements; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2019; 256p. [Google Scholar]

- Villamena, F.; Forman, H.J. Molecular Basis of Oxidative Stress: Chemistry, Toxicology, Disease Pathogenesis, Diagnosis, and Therapeutics; John Wiley & Sons, Inc.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2025; ISBN 9781119790266. [Google Scholar]

- Shrestha, S.; Wang, B.; Dutta, P. Nanoparticle processing: Understanding and controlling aggregation. Adv. Colloid Interface Sci. 2020, 279, 102162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Environment Canada. Biological Test Method: Acute Lethality Test Using Rainbow Trout Environmental Protection Series; Report EPS 1/RM/9; Environment Canada: Gatineau, QC, Canada, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Finney, D.J. Statistical Method in Biological Assay; Hafner Publishing Company: New York, NY, USA, 1964; 668p. [Google Scholar]

- Bhajiwala, H.M.; Patil, H.R.; Gupta, V. Studies of amino acids for inhibition of aldol condensation and dissolution of polymeric product of aldehyde in alkaline media. Appl. Petrochem. Res. 2013, 3, 17–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- dos Santos, M.M.; Snyder, S.A. Occurrence of polymer additives 1,3-Diphenylguanidine (DPG), N-(1,3-Dimethylbutyl)-N′-phenyl-1,4-benzenediamine (6PPD), and chlorinated byproducts in drinking water: Contribution from plumbing polymer materials. Environ. Sci. Technol. Lett. 2023, 10, 885–890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maxwell, K.L.; Bona, D.; Liu, C.; Arrowsmith, C.H.; Edwards, A.M. Refolding out of guanidine hydrochloride is an effective approach for high-throughput structural studies of small proteins. Protein Sci. 2003, 12, 2073–2080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blanco, F.; Kelly, B.; Sánchez-Sanz, G.; Trujillo, C.; Alkorta, I.; Elguero, J.; Rozas, I. Non-covalent interactions: Complexes of guanidinium with DNA and RNA nucleobases. J. Phys. Chem. B 2013, 117, 11608–11616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gasmi, A.; Peana, M.; Arshad, M.; Butnariu, M.; Menzel, A.; Bjørklund, G. Krebs cycle: Activators, inhibitors and their roles in the modulation of carcinogenesis. Arch. Toxicol. 2021, 95, 1161–1178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cafferty, B.J.; Wong, A.S.Y.; Semenov, S.N.; Belding, L.; Gmür, S.; Huck, W.T.S.; Whitesides, G.M. Robustness, entrainment, and hybridization in dissipative molecular networks, and the origin of life. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2019, 141, 8289–8295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grady, S.R.; Wang, J.K.; Dekker, E.E. Steady-state kinetics and inhibition studies of the aldol condensation reaction catalyzed by bovine liver and Escherichia coli 2-keto-4-hydroxyglutarate aldolase. Biochemistry 1981, 20, 2497–2502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brooke, D.N.; Nielsen, I.R.; Dobson, S.; Howe, P.D. Environmental Hazard Assessment: Di-(2-ethylhexyl) Phthalate; TSD 2; UK Department of the Environment: Garston, UK, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- European Chemical Agency Registration Dossier. Available online: https://echa.europa.eu/registration-dossier/-/registered-dossier/14992/6/1 (accessed on 1 November 2025).

- Delahaut, V.; Chen, P.J.; Tan, S.W.; Wu, W.L.; Rašković, B.; Salvado, M.S.; Bervoets, L.; Blust, R.; De Boeck, G. Toxicity and bioaccumulation of Cadmium, Copper and Zinc in a direct comparison at equitoxic concentrations in common carp (Cyprinus carpio) juveniles. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0220485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brix, K.V.; Tellis, M.S.; Crémazyc, A.; Wood, C.M. Characterization of the effects of binary metal mixtures on short-term uptake of Ag, Cu, and Ni by rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss). Aquat. Toxicol. 2016, 180, 236–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubé, M.; Auclair, J.; Hanana, H.; Turcotte, P.; Gagnon, C.; Gagné, F. Gene expression changes and toxicity of selected rare earth elements in rainbow trout juveniles. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. Part C Toxicol. Pharmacol. 2019, 223, 88–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, P.J.; Tan, S.W.; Wu, W.L. Stabilization or oxidation of nanoscale zerovalent iron at environmentally relevant exposure changes bioavailability and toxicity in medaka fish. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2012, 46, 8431–8439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Auclair, J.; Roubeau Dumont, E.; Gagné, F. Lethal and sublethal toxicity of nanosilver and carbon nanotube composites to Hydra vulgaris—A toxicogenomic approach. Nanomaterials 2024, 14, 1955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Auclair, J.; Quinn, B.; Peyrot, C.; Wilkinson, K.J.; Gagné, F. Detection, biophysical effects, and toxicity of polystyrene nanoparticles to the cnidarian Hydra attenuata. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. Int. 2020, 27, 11772–11781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deavall, D.G.; Martin, E.A.; Horner, J.M.; Roberts, R. Drug-Induced Oxidative Stress and Toxicity. J. Toxicol. 2012, 2012, 6454600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, D.; Falodah, F.A.; Almutairi, B.; Alkahtani, S.; Alarifi, S. Assessment of DNA damage and oxidative stress in juvenile Channa punctatus (Bloch) after exposure to multi-walled carbon nanotubes. Environ. Toxicol. 2020, 35, 359–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gagné, F.; André, C.; Smyth, S.-A. Screening of municipal effluents with the peroxidase toxicity assay. Discov. Water 2024, 4, 101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ichihara, M.; Asakawa, D.; Yamamoto, A.; Sudo, M. Quantitation of guanidine derivatives as representative persistent and mobile organic compounds in water: Method development. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2023, 415, 1953–1965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Compounds | Pyr-Glyox (IC20 mg/L) | Trout Toxicity (LC50 mg/L) | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dibutylphthalate (DBP) | 35 | 1.6 | [24] |

| 1,3-Diphenylguanidine (1.3-DPG) | 12 | 4.2 | [25] |

| Copper Cu(II) | 12 | 0.1 | [26] |

| Silver Ag(I) | 1 | 0.02 | [26] |

| Zinc Zn(II) | 41 | 1.6 | [26,27] |

| Samarium Sm(III) | 24 | 2 | [28] |

| Cerium Ce(IV) | 77 | 95 | [28] |

| nFe2O3 | 146 | 100 (Oryzias latipe embryo) | [29] |

| Polystyrene nanoplastic (PSNP) | 150 | >100 | This work (Section 2.3) |

| Carbon-walled nanotubes (CNTs) | 17 | 22 (Channa punctatus juvenile) | [30] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Gagné, F.; André, C. The Pyruvate–Glyoxalate Pathway as a Toxicity Assessment Tool of Xenobiotics: Lessons from Prebiotic Chemistry. J. Xenobiot. 2025, 15, 198. https://doi.org/10.3390/jox15060198

Gagné F, André C. The Pyruvate–Glyoxalate Pathway as a Toxicity Assessment Tool of Xenobiotics: Lessons from Prebiotic Chemistry. Journal of Xenobiotics. 2025; 15(6):198. https://doi.org/10.3390/jox15060198

Chicago/Turabian StyleGagné, François, and Chantale André. 2025. "The Pyruvate–Glyoxalate Pathway as a Toxicity Assessment Tool of Xenobiotics: Lessons from Prebiotic Chemistry" Journal of Xenobiotics 15, no. 6: 198. https://doi.org/10.3390/jox15060198

APA StyleGagné, F., & André, C. (2025). The Pyruvate–Glyoxalate Pathway as a Toxicity Assessment Tool of Xenobiotics: Lessons from Prebiotic Chemistry. Journal of Xenobiotics, 15(6), 198. https://doi.org/10.3390/jox15060198