Indoor Airborne VOCs from Water-Based Coatings: Transfer Dynamics and Health Implications †

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

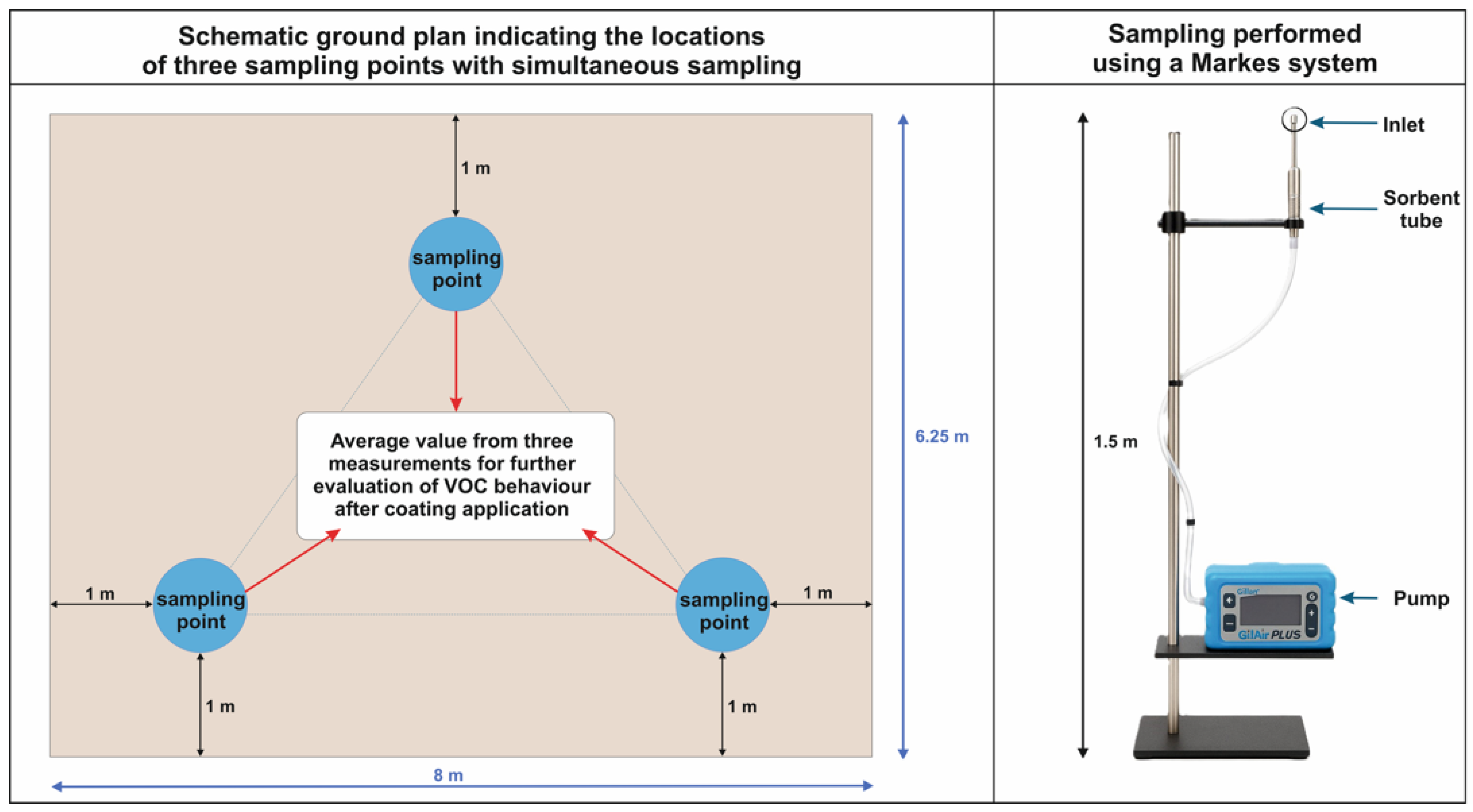

2.2. Sampling Procedure

2.3. Analytical Methods

2.4. Statistical Evaluation

Statistical Robustness and Component Retention Criteria

2.5. Potential Risk Assessment of Chemical Substances in Relation to Sick Building Syndrome (SBS)

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Characterisation of Organic Compounds in Indoor Air and Water-Based Varnishes

3.1.1. Reproductive Toxicants

3.1.2. Mutagens in Indoor Air from Polyurethane and Acryl-Polyurethane Lacquers

3.1.3. Carcinogens and Potential Carcinogens in Indoor Air from Polyurethane and Acryl–Polyurethane Lacquers

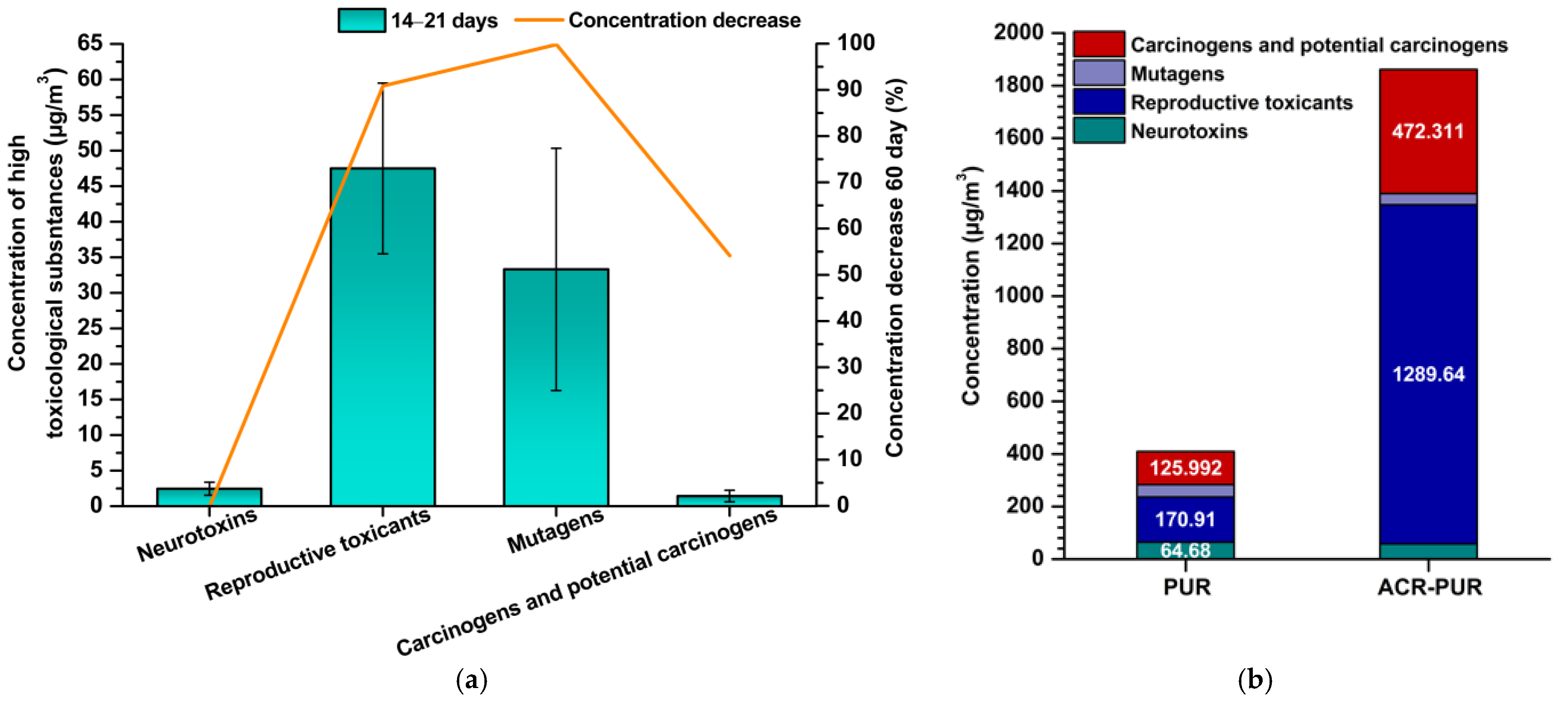

3.2. Toxicological Profile of PUR and ACR–PUR Coatings

3.3. Toxicological Assessment of Indoor Air Following Coating Application

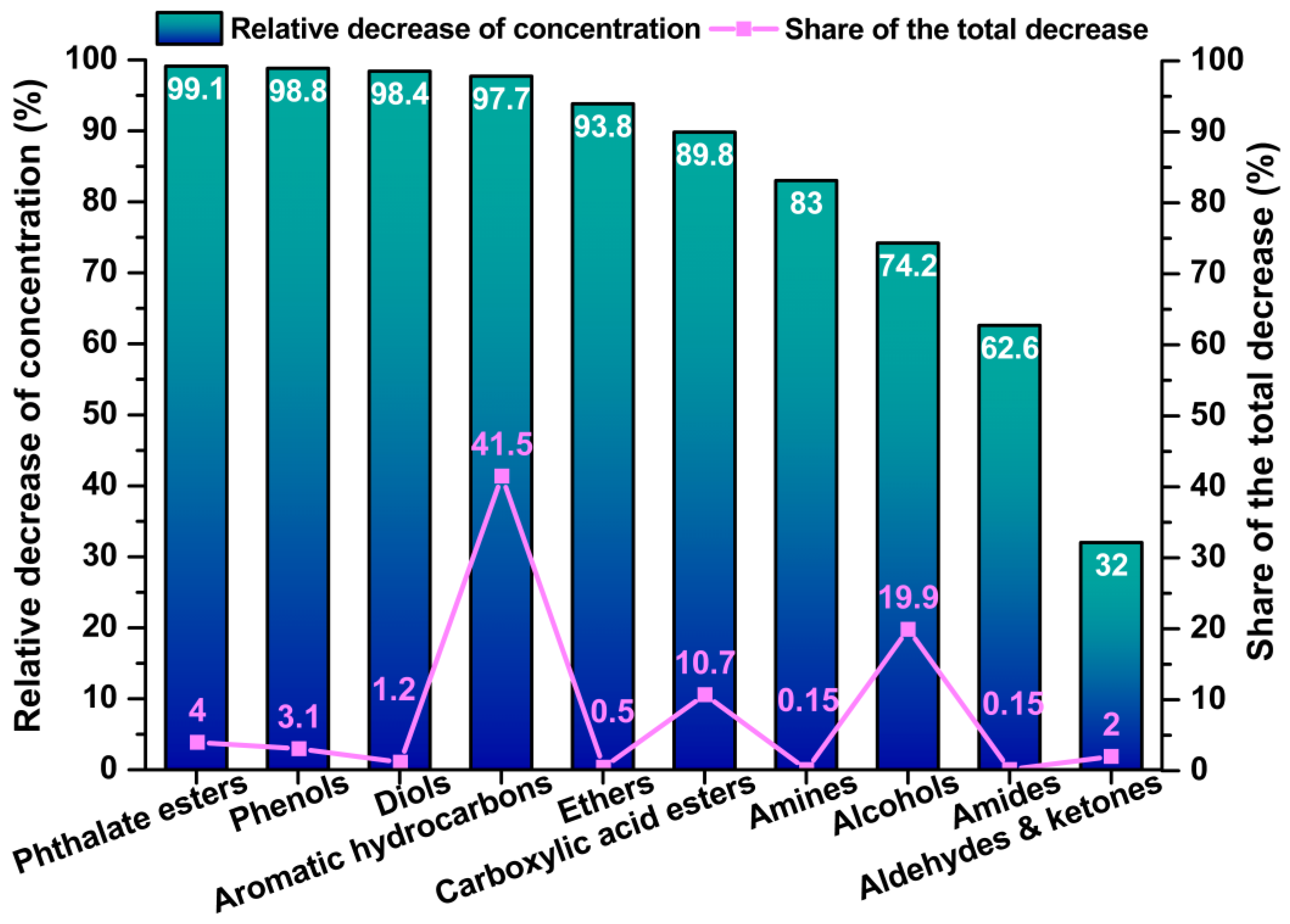

3.4. Integrated Evaluation of Emission Behaviour and Exposure Relevance

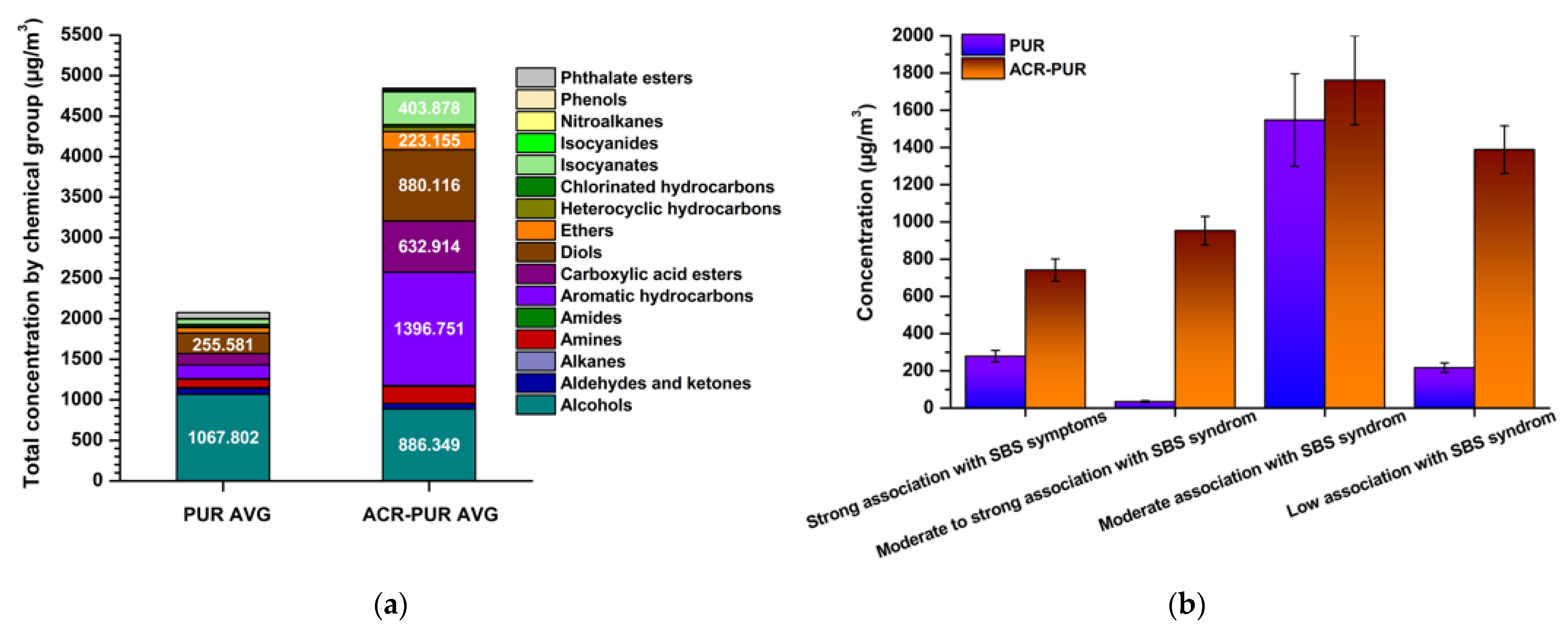

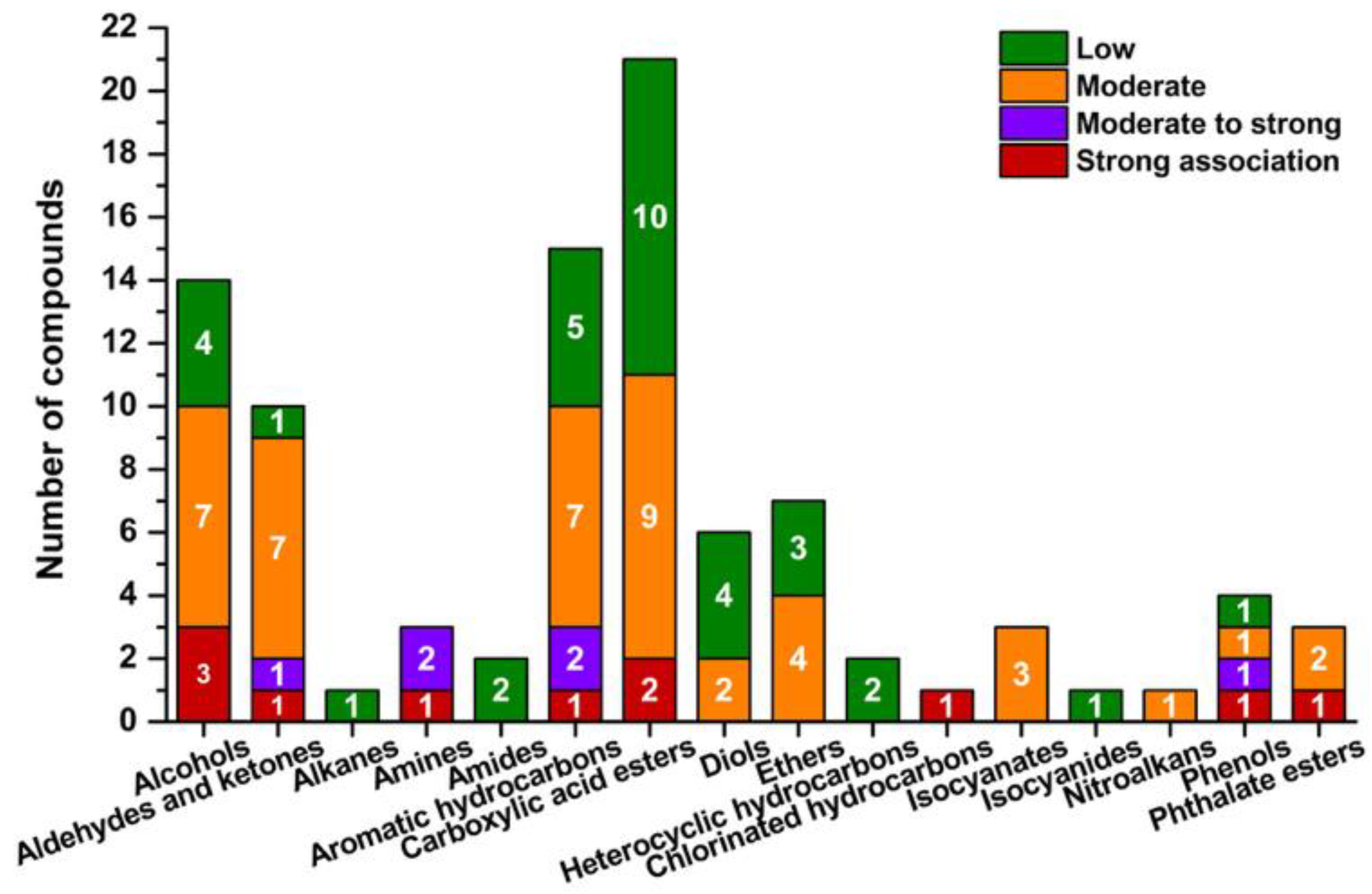

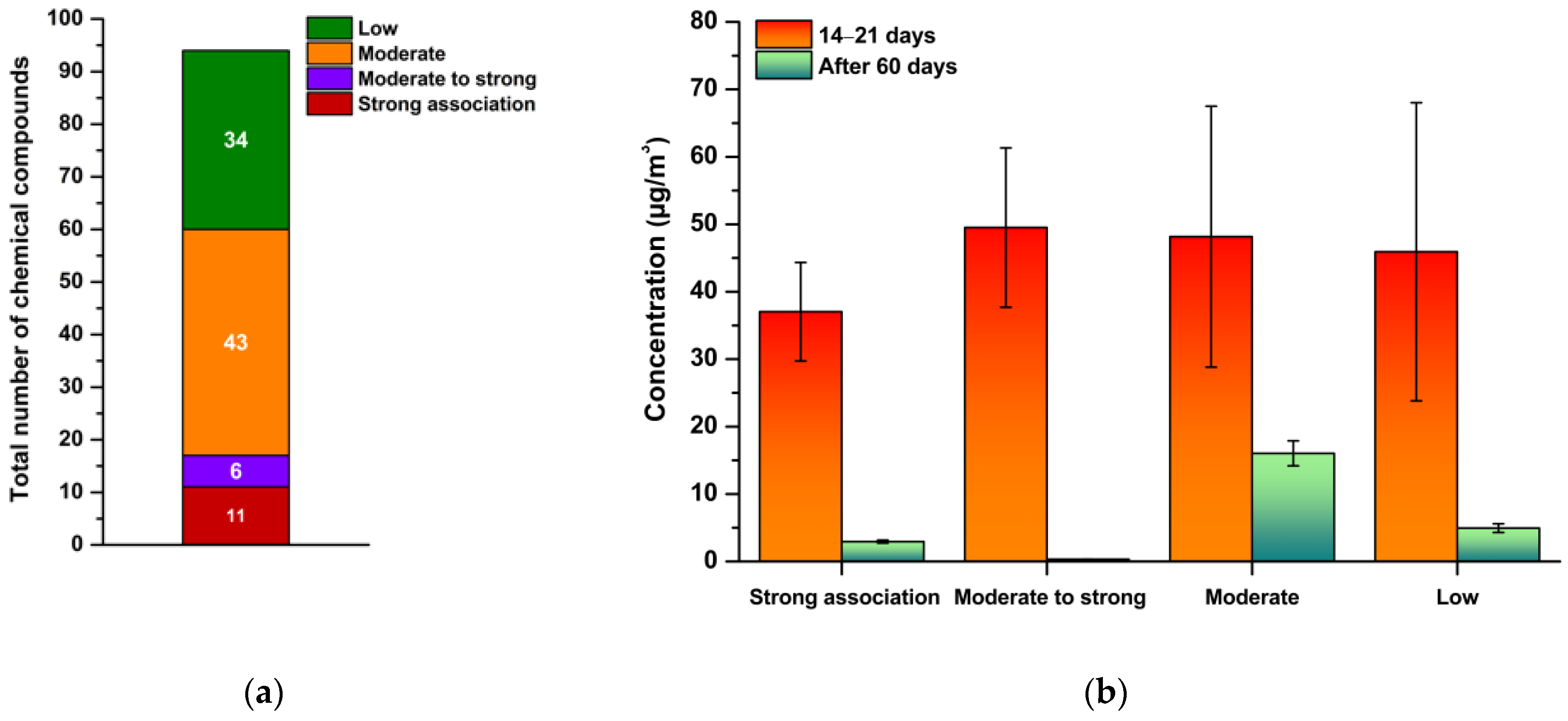

3.5. Sick Building Syndrome

3.5.1. Comparison of Coatings

3.5.2. Indoor Air Quality After Coating Application

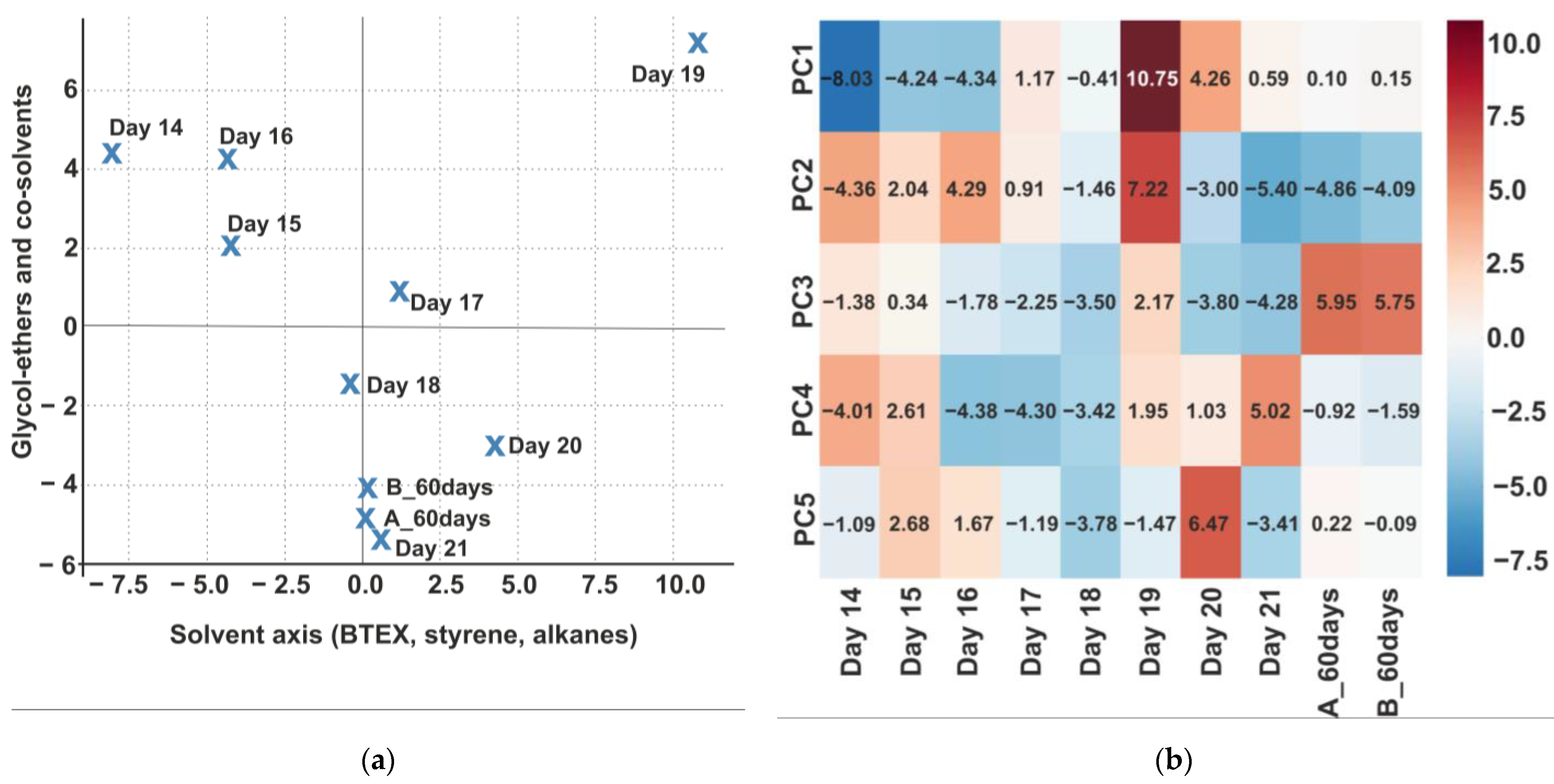

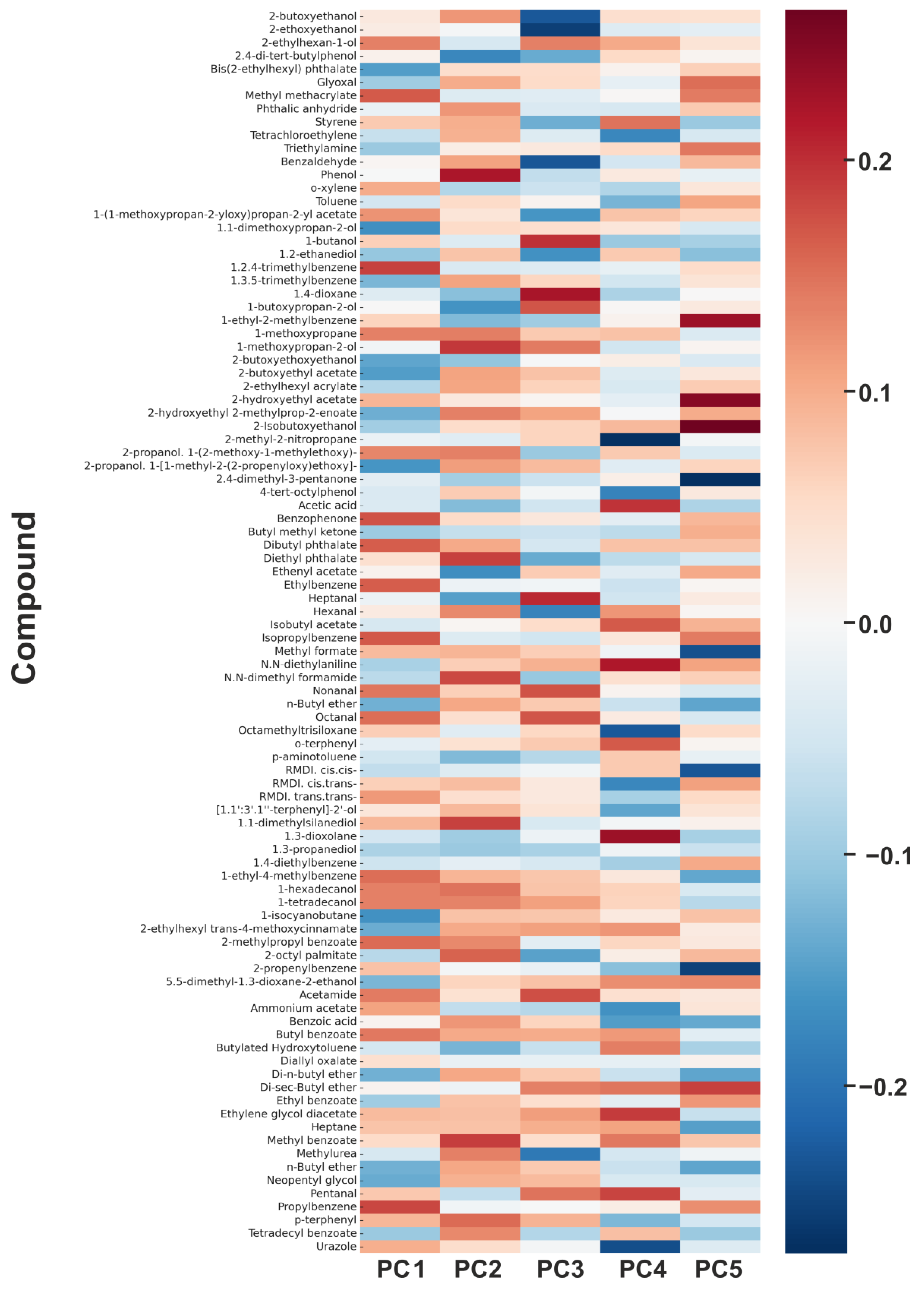

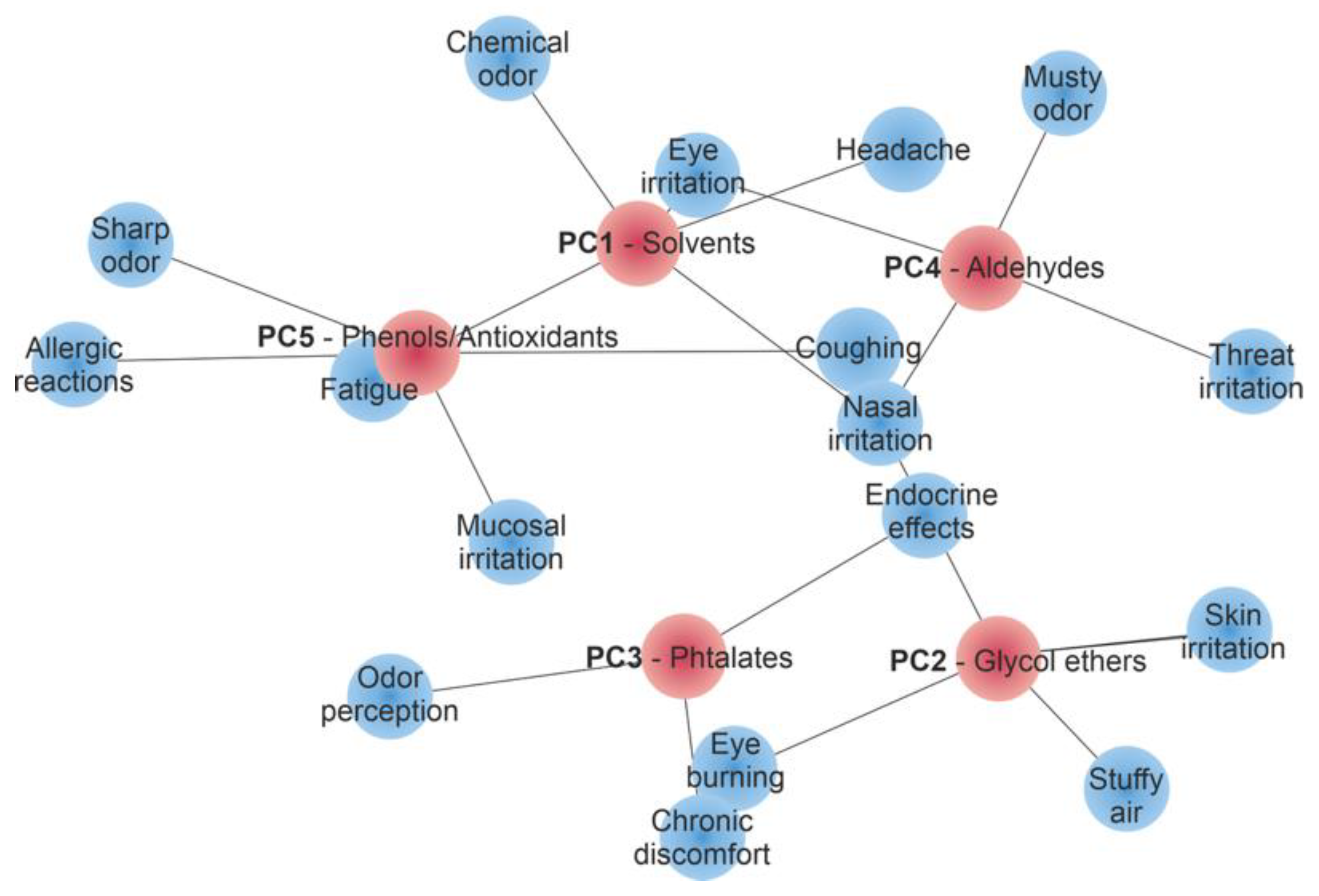

3.5.3. Principal Component Analysis (PCA) of VOC Profiles and Their Relevance to SBS

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ACGIH | American Conference of Governmental Industrial Hygienists |

| ACR–PUR | Acrylate–Polyurethane |

| AI | Artificial Intelligence |

| AT | Acute Toxicity |

| BHT | Butylated Hydroxytoluene |

| CASRN | Chemical Abstracts Service Registry Number |

| CIS | Cooled Injection System |

| CLP | Classification, Labelling and Packaging |

| DBP | Dibutyl Phthalate |

| DEHP | Bis(2-ethylhexyl)phthalate |

| DEP | Diethyl Phthalate |

| DMF | N,N-Dimethylformamide |

| DNT | Developmental Neurotoxicity |

| ECHA | European Chemicals Agency |

| EGEE | 2-Ethoxyethanol |

| EU | European Union |

| GHS | Globally Harmonised System of Classification and Labelling of Chemicals |

| IARC | International Agency for Research on Cancer |

| ISO | International Organisation for Standardisation |

| LC/MS | Liquid Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry |

| MBK | Methyl Butyl Ketone/2-hexanone |

| MDF | Medium-Density Fibreboard |

| NIOSH | National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (U.S.) |

| OEL | Occupational Exposure Limit |

| OECD | Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development |

| OSHA | Occupational Safety and Health Administration (U.S. Department of Labour) |

| PCA | Principal Component Analysis |

| PC | Principal Component |

| PC1–PC5 | Principal Components 1 to 5 (as identified by PCA) |

| PUR | Polyurethane |

| RE | Repeated Exposure |

| Repr. | Reproductive Toxicant |

| RMDI | Residual Polymeric Methylene Diphenyl Diisocyanate |

| SBS | Sick Building Syndrome |

| SDS | Safety Data Sheet |

| SE | Single Exposure |

| STOT | Specific Target Organ Toxicity |

| SVOC | Semi-Volatile Organic Compounds |

| TD-GC/MS | Thermal Desorption-Gas Chromatography/Mass Spectrometry |

| TG | Test Guideline |

| TVOC | Total Volatile Organic Compound |

| UBA | Umweltbundesamt (German Environment Agency) |

| USA | United States of America |

| UV | Ultraviolet |

| VSB | VSB—Technical University of Ostrava |

| VOC | Volatile Organic Compound |

| VVOC | Very Volatile Organic Compound |

| WHO | World Health Organisation |

| U.S. EPA | United States Environmental Protection Agency |

References

- Wu, F.; Jacobs, D.; Mitchell, C.; Miller, D.; Karol, M.H. Improving Indoor Environmental Quality for Public Health: Impediments and Policy Recommendations. Environ. Health Perspect. 2007, 115, 953–957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orkomi, A.A. Impacts of Environmental Parameters on Sick Building Syndrome Prevalence among Residents: A Walk-through Survey in Rasht, Iran. Arch Public Health 2024, 82, 247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kishi, R.; Norbäck, D.; Araki, A. Indoor Environmental Quality and Health Risk toward Healthier Environment for All; Current Topics in Environmental Health and Preventive Medicine; Springer: Singapore, 2020; ISBN 978-981-329-181-2. [Google Scholar]

- .Wolkoff, P.; Clausen, P.A.; Jensen, B.; Nielsen, G.D.; Wilkins, C.K. Are We Measuring the Relevant Indoor Pollutants? Indoor Air 1997, 7, 92–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knudsen, H.N.; Kjaer, U.D.; Nielsen, P.A.; Wolkoff, P. Sensory and Chemical Characterization of VOC Emissions from Building Products: Impact of Concentration and Air Velocity. Atmos. Environ. 1999, 33, 1217–1230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, S.; Liang, W. Volatile Organic Compounds and Odor Emissions Characteristics of Building Materials and Comparisons with the On-Site Measurements during Interior Construction Stages. Build. Environ. 2024, 252, 111257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Shen, J.; Shao, Y.; Dong, H.; Li, Z.; Shen, X. Volatile Organic Compounds and Odor Emissions from Veneered Particleboards Coated with Water-Based Lacquer Detected by Gas Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry/Olfactometry. Eur. J. Wood Prod. 2019, 77, 771–781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Parliament and Council Directive 2004/42/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 21 April 2004 on the Limitation of Emissions of Volatile Organic Compounds Due to the Use of Organic Solvents in Certain Paints and Varnishes and Vehicle Refinishing Products and Amending Directive 1999/13/EC. Off. J. 2004, L 143, 0087–0096.

- EN 71-9; Safety of Toys–Part 9: Organic Chemical Compounds–Requirements. European Committee for Standardization (CEN): Brussels, Belgium, 2005.

- Gavande, V.; Mahalingam, S.; Kim, J.; Lee, W.-K. Optimization of UV-Curable Polyurethane Acrylate Coatings with Hexagonal Boron Nitride (hBN) for Improved Mechanical and Adhesive Properties. Polymers 2024, 16, 2544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, C.; Zhang, Y.-J.; Liu, L.-Y.; Wang, F.; Guo, Y. Exposure to Phthalates and Correlations with Phthalates in Dust and Air in South China Homes. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 782, 146806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olkowska, E.; Ratajczyk, J.; Wolska, L. Determination of Phthalate Esters in Air with Thermal Desorption Technique–Advantages and Disadvantages. TrAC Trends Anal. Chem. 2017, 91, 77–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Xie, D.; He, L.; Zhao, A.; Wang, L.; Kreisberg, N.M.; Jayne, J.; Liu, Y. Dynamics of Di-2-Ethylhexyl Phthalate (DEHP) in the Indoor Air of an Office. Build. Environ. 2022, 223, 109446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anh, H.Q.; Nguyen, H.M.N.; Do, T.Q.; Tran, K.Q.; Minh, T.B.; Tran, T.M. Air Pollution Caused by Phthalates and Cyclic Siloxanes in Hanoi, Vietnam: Levels, Distribution Characteristics, and Implications for Inhalation Exposure. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 760, 143380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, W.; Greer, S.; Howard-Reed, C.; Persily, A.; Zhang, Y. VOC Emissions from a LIFE Reference: Small Chamber Tests and Factorial Studies. Build. Environ. 2012, 57, 282–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO 16000-9:2024; Indoor Air-Part 9: Determination of the Emission of Volatile Organic Compounds from Samples of Building Products and Furnishing-Emission Test Chamber Method. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2024.

- Wolkoff, P.; Wilkins, C.K.; Clausen, P.A.; Nielsen, G.D. Organic Compounds in Office Environments-Sensory Irritation, Odor, Measurements and the Role of Reactive Chemistry. Indoor Air 2006, 16, 7–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO 16017-2:2003; Indoor, Ambient and Workplace Air-Sampling and Analysis of Volatile Organic Compounds by Sorbent Tube/Thermal Desorption/Capillary Gas Chromatography Part 2: Diffusive Sampling. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2023.

- ISO 16000-5:2007; Indoor Air Part 5: Sampling Strategy for Volatile Organic Compounds (VOCs). International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2007.

- Marzocca, A.; Di Gilio, A.; Farella, G.; Giua, R.; De Gennaro, G. Indoor Air Quality Assessment and Study of Different VOC Contributions within a School in Taranto City, South of Italy. Environments 2017, 4, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EN 16798-1:2019; Energy Performance of Buildings-Ventilation for Buildings-Part 1: Indoor Environmental Input Parameters for Design and Assessment of Energy Performance of Buildings Addressing Indoor Air Quality, Thermal Environment, Lighting and Acoustics-Module M1-6. European Committee for Standardization: Brussels, Belgium, 2019.

- Nazaroff, W.W.; Weschler, C.J. Cleaning Products and Air Fresheners: Exposure to Primary and Secondary Air Pollutants. Atmos. Environ. 2004, 38, 2841–2865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norbäck, D.; Wålinder, R.; Wieslander, G.; Smedje, G.; Erwall, C.; Venge, P. Indoor Air Pollutants in Schools: Nasal Patency and Biomarkers in Nasal Lavage. Allergy 2000, 55, 163–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ait Bamai, Y. Semi-Volatile Organic Compounds (SVOCs): Phthalates and Phosphorous Frame Retardants and Health Risks. In Indoor Environmental Quality and Health Risk Toward Healthier Environment for All; Kishi, R., Norbäck, D., Araki, A., Eds.; Current Topics in Environmental Health and Preventive Medicine; Springer: Singapore, 2020; pp. 159–178. ISBN 978-981-329-181-2. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, W.; Shen, X.; Zhang, S.; Lv, R.; Liu, M.; Xu, W.; Chen, Y.; Wang, H. Research on Very Volatile Organic Compounds and Odors from Veneered Medium Density Fiberboard Coated with Water-Based Lacquers. Molecules 2022, 27, 3626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alapieti, T.; Castagnoli, E.; Salo, L.; Mikkola, R.; Pasanen, P.; Salonen, H. The Effects of Paints and Moisture Content on the Indoor Air Emissions from Pinewood (Pinus sylvestris) Boards. Indoor Air 2021, 31, 1563–1576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Zhu, X.; Qin, X.; Wang, W.; Hu, Y.; Yuan, D. Identification and Characterization of Odorous Volatile Organic Compounds Emitted from Wood-Based Panels. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2020, 192, 348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- CASRN 117-81-7; Di(2-Ethylhexyl)Phthalate (DEHP). U.S. Environmental Protection Agency: Washington, DC, USA, 1988.

- Rowdhwal, S.S.S.; Chen, J. Toxic Effects of Di-2-Ethylhexyl Phthalate: An Overview. BioMed Res. Int. 2018, 2018, 1750368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wakayama, T.; Ito, Y.; Sakai, K.; Miyake, M.; Shibata, E.; Ohno, H.; Kamijima, M. Comprehensive Review of 2-Ethyl-1-Hexanol as an Indoor Air Pollutant. J. Occup. Health 2019, 61, 19–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maestre-Batlle, D.; Huff, R.D.; Schwartz, C.; Alexis, N.E.; Tebbutt, S.J.; Turvey, S.; Bølling, A.K.; Carlsten, C. Dibutyl Phthalate Augments Allergen-Induced Lung Function Decline and Alters Human Airway Immunology: A Randomized Crossover Study. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2020, 202, 672–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Yuan, F.; Ye, H.; Bu, Z. Measurement of Phthalates in Settled Dust in University Dormitories and Its Implications for Exposure Assessment. Atmosphere 2023, 14, 612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fromme, H.; Sysoltseva, M.; Schieweck, A.; Röhl, C.; Gerull, F.; Burghardt, R.; Gessner, A.; Papavlassopoulos, H.; Völkel, W.; Schober, W. Very Volatile and Volatile Organic Compounds (VVOCs/VOCs) and Endotoxins in the Indoor Air of German Schools and Apartments (LUPE10). Atmos. Environ. 2025, 351, 121178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, R.; Verma, V.; Thakur, M.; Singh, G.; Bhargava, B. A Systematic Review on Mitigation of Common Indoor Air Pollutants Using Plant-Based Methods: A Phytoremediation Approach. Air Qual. Atmos. Health 2023, 16, 1501–1527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Campagnolo, D.; Saraga, D.E.; Cattaneo, A.; Spinazzè, A.; Mandin, C.; Mabilia, R.; Perreca, E.; Sakellaris, I.; Canha, N.; Mihucz, V.G.; et al. VOCs and Aldehydes Source Identification in European Office Buildings-The OFFICAIR Study. Build. Environ. 2017, 115, 18–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duncan, S.M.; Sexton, K.G.; Turpin, B.J. Oxygenated VOCs, Aqueous Chemistry, and Potential Impacts on Residential Indoor Air Composition. Indoor Air 2018, 28, 198–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Su, T.; Wang, L.; Wang, N.; Xue, Y.; Dai, W.; Lee, S.C.; Cao, J.; Ho, S.S.H. Evaluation and Characterization of Volatile Air Toxics Indoors in a Heavy Polluted City of Northwestern China in Wintertime. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 662, 470–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tanaka-Kagawa, T.; Uchiyama, S.; Matsushima, E.; Sasaki, A.; Kobayashi, H.; Kobayashi, H.; Yagi, M.; Tsuno, M.; Arao, M.; Ikemoto, K.; et al. Survey of Volatile Organic Compounds Found in Indoor and Outdoor Air Samples from Japan. Kokuritsu Iyakuhin Shokuhin Eisei Kenkyusho Hokoku 2005, 123, 27–31. [Google Scholar]

- CASRN 123-91-1; Supplement to the Risk Evaluation for 1,4-Dioxane. U.S. Environmental Protection Agency: Washington, DC, USA, 2024.

- Adamová, T.; Hradecký, J.; Pánek, M. Volatile Organic Compounds (VOCs) from Wood and Wood-Based Panels: Methods for Evaluation, Potential Health Risks, and Mitigation. Polymers 2020, 12, 2289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palmiotto, G.; Pieraccini, G.; Moneti, G.; Dolara, P. Determination of the Levels of Aromatic Amines in Indoor and Outdoor Air in Italy. Chemosphere 2001, 43, 355–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, Y.; Xue, J.; Kannan, K. Occurrence of Benzophenone-3 in Indoor Air from Albany, New York, USA, and Its Implications for Inhalation Exposure. Sci. Total Environ. 2015, 537, 304–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, W.; Yang, X.; Song, Z.; Geng, J.; Liu, C.; Zhang, N.; Qi, X. Research on the Tribological Behavior of Polyurethane Acrylate Coatings with Different Matrix Constituents as Well as Graphite and PTFE. Polymers 2025, 17, 1121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghaffarianhoseini, A.; AlWaer, H.; Omrany, H.; Ghaffarianhoseini, A.; Alalouch, C.; Clements-Croome, D.; Tookey, J. Sick Building Syndrome: Are We Doing Enough? Archit. Sci. Rev. 2018, 61, 99–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norback, D.; Torgen, M.; Edling, C. Volatile Organic Compounds, Respirable Dust, and Personal Factors Related to Prevalence and Incidence of Sick Building Syndrome in Primary Schools. Occup. Environ. Med. 1990, 47, 733–741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schripp, T.; Nachtwey, B.; Toelke, J.; Salthammer, T.; Uhde, E.; Wensing, M.; Bahadir, M. A Microscale Device for Measuring Emissions from Materials for Indoor Use. Anal Bioanal Chem 2007, 387, 1907–1919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ulker, O.C.; Ulker, O.; Hiziroglu, S. Volatile Organic Compounds (VOCs) Emitted from Coated Furniture Units. Coatings 2021, 11, 806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uhde, E.; Salthammer, T. Impact of Reaction Products from Building Materials and Furnishings on Indoor Air Quality-A Review of Recent Advances in Indoor Chemistry. Atmos. Environ. 2007, 41, 3111–3128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pei, Y.; Liu, N.; Liu, S.; Guan, H.; Guo, Z.; Li, Q.; Han, W.; Cai, H. Investigation of Odor Emissions from Coating Products: Key Factors and Key Odorants. Front. Environ. Sci. 2022, 10, 1039842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DePolo, G.; Iedema, P.; Shull, K.; Hermans, J. Comprehensive Characterization of Drying Oil Oxidation and Polymerization Using Time-Resolved Infrared Spectroscopy. Macromolecules 2024, 57, 8263–8276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- German Environment Agency. Assessment of indoor air contamination using reference and guideline values. Federal Health Gazette 2007, 50, 990–1005. (In German) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. WHO Guidelines for Indoor Air Quality: Selected Pollutants; Adamkiewicz, G., World Health Organization, Eds.; World Health Organization, Regional Office for Europe: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2010; ISBN 978-92-890-0213-4. [Google Scholar]

- Wolkoff, P. Indoor Air Pollutants in Office Environments: Assessment of Comfort, Health, and Performance. Int. J. Hyg. Environ. Health 2013, 216, 371–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OSHA Toluene. Available online: https://www.osha.gov/chemicaldata/89 (accessed on 9 November 2025).

- NIOSH Toluene. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/niosh/npg/npgd0619.html (accessed on 9 November 2025).

- ACGIH Toluene. Available online: https://www.acgih.org/toluene (accessed on 9 November 2025).

- Logue, J.M.; Price, P.N.; Sherman, M.H.; Singer, B.C. A Method to Estimate the Chronic Health Impact of Air Pollutants in U.S. Residences. Environ. Health Perspect. 2012, 120, 216–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salthammer, T. TVOC-Revisited. Environ. Int. 2022, 167, 107440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godish, T.; Spengler, J.D. Relationships between Ventilation and Indoor Air Quality: A Review. Indoor Air 1996, 6, 135–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, L.; Hajeb, P.; Fauser, P.; Vorkamp, K. Endocrine Disrupting Chemicals in Indoor Dust: A Review of Temporal and Spatial Trends, and Human Exposure. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 874, 162374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wolkoff, P. Indoor Air Humidity, Air Quality, and Health–An Overview. Int. J. Hyg. Environ. Health 2018, 221, 376–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Property | Water-Based PUR Coating | Water-Based ACR–PUR Coating |

|---|---|---|

| Binder | Polyurethane dispersion | Blend of acrylates and polyurethane |

| VOC profile | Lower; may contain reactive residues (e.g., isocyanates) | Higher initial volatility due to acrylate esters and aldehydes |

| Emission dynamics | More stable, slower VOC release | Faster and more intense VOC release |

| UV resistance | Lower | Higher (due to acrylate component) |

| Application properties | Longer drying time; requires precise application | Faster drying, better adhesion |

| Toxicological Category | Classification Source/Authority | Criteria and Scope | Examples of Classification Codes/Endpoints | Relevance to SBS Symptoms |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Carcinogenicity | CLP, IARC-U.S. EPA | Substances classified as Carcinogenicity 1A, 1B, 2 based on human or animal data | Carc. 1A (proven), Carc. 2 (suspected) | Chronic risk from prolonged exposure |

| Reproductive toxicity | CLP/GHS, Annex I Section 3.7 | Effects on fertility, development, and lactation | Repr. 1A, 1B, 2 | Fertility, developmental, and endocrine effects |

| Mutagenicity (germ cell) | CLP/GHS, Annex I Section 3.5 | Induction of heritable mutations in germ cells | Muta. 1A, 1B, 2 | Genetic stability, chronic SBS effects |

| Neurotoxicity | ECHA guidance, OECD TG 426, TG 443 | Developmental and adult neurotoxicity, DNT cohorts | Based on DNT data, not codified in CLP | Headache, dizziness, cognitive impairment |

| Acute toxicity | CLP Annex VI, ECHA, SDS | Systemic effects after single exposure via oral, dermal, and inhalation | AT1–AT4, NC; H301, H302, H312, H330, H331, H332 | Nausea, dizziness, and respiratory distress |

| Skin/eye irritation | CLP/GHS, SDS | Local effects, reversible or irreversible | Skin 1/1A/1B, Skin 2, Eye 1, Eye 2/2A/2B | Burning eyes, mucosal irritation, and skin discomfort |

| Specific Target Organ Toxicity (STOT) | CLP/GHS Annex I Section 3.8 | Organ effects after single (SE) or repeated (RE) exposure | STOT SE 1–3, STOT RE 1–2 | Burning eyes, mucosal irritation, and skin discomfort |

| Group | Key Compounds | Coating with a Higher Concentration |

|---|---|---|

| Neurotoxins | 1,3-Dioxolane | Acrylate–polyurethane |

| Reproductive toxicants | Toluene, styrene, phthalates | Acrylate–polyurethane (toluene, styrene), Polyurethane (phthalates) |

| Mutagens | Benzene, glyoxal | Polyurethane (benzene), Acrylate–polyurethane (glyoxal) |

| Carcinogens | Residual polymeric methylene-diphenyl diisocyanate (RMDI) isomers, tetrachloroethylene | Acrylate–polyurethane |

| Group | Key Compounds | Temporal Behaviour |

|---|---|---|

| Neurotoxins | 1,3-Dioxolane | Stable, persistent |

| Reproductive toxicants | Toluene, styrene, phthalates | Sharp decline; styrene—partly persistent |

| Mutagens | Benzene, phenol | Near-complete reduction |

| Carcinogens | Ethenyl acetate, acetamide, RMDI isomers | Modest decline; some persistent |

| Chemical Group | SBS-Related Risk | Dominant in |

|---|---|---|

| Amines | Sensitisation, odour | ACR–PUR |

| Aromatic hydrocarbons | Neurotoxicity, irritation | ACR–PUR |

| Isocyanates | Respiratory sensitisation | ACR–PUR |

| Esters | Mucosal irritation | ACR–PUR |

| Alcohols | High volatility, odour | PUR |

| Phenols | Mucosal irritation | ACR–PUR |

| Component | Top 10 Contributing Compounds (Loading) |

|---|---|

| PC1 Solvent fraction | Octanal (−0.396), Hexanal (0.393), 2-butoxyethoxyethanol (0.389), Styrene (−0.379), 2-butoxyethanol (0.372), o-xylene (−0.364), Nonanal (0.351), 1,2,4-trimethylbenzene (−0.342), 1-methoxypropan-2-ol (0.335), Benzaldehyde (0.328) |

| PC2 Glycol ethers and their esters | 1-methoxypropan-2-ol (0.402), Heptane (0.401), o-xylene (0.397), Styrene (0.383), 2-butoxyethanol (−0.372), Hexanal (−0.361), Phenol (0.348), 2,4-di-tert-butylphenol (0.342), Nonanal (−0.334), 1,2,4-trimethylbenzene (0.329) |

| PC3 Co-solvents and rheological modifiers | Toluene (−0.526), Bis(2-ethylhexyl) phthalate (0.498), Diethyl phthalate (0.482), Dibutyl phthalate (0.467), Nonanal (0.455), Hexanal (−0.442), Octanal (0.437), Benzaldehyde (−0.421), Styrene (0.410), Heptane (−0.397) |

| PC4 Aldehydic degradation products | Butylated Hydroxytoluene (0.440), Benzaldehyde (0.432), Phenol (−0.425), 2,4-di-tert-butylphenol (0.418), Octanal (−0.407), Hexanal (0.395), 1-methoxypropan-2-ol (−0.383), Nonanal (0.379), Styrene (−0.366), Diethyl phthalate (0.351) |

| PC5 Phenolic antioxidants and stabilisers | Phenol (0.476), o-xylene (−0.386), 2,4-di-tert-butylphenol (0.374), Butylated Hydroxytoluene (−0.362), Toluene (0.359), Bis(2-ethylhexyl) phthalate (−0.345), Diethyl phthalate (0.332), Dibutyl phthalate (−0.321), Hexanal (0.309), Nonanal (0.301) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Růžičková, J.; Raclavská, H.; Kucbel, M.; Kantor, P.; Švédová, B.; Slamová, K. Indoor Airborne VOCs from Water-Based Coatings: Transfer Dynamics and Health Implications. J. Xenobiot. 2025, 15, 197. https://doi.org/10.3390/jox15060197

Růžičková J, Raclavská H, Kucbel M, Kantor P, Švédová B, Slamová K. Indoor Airborne VOCs from Water-Based Coatings: Transfer Dynamics and Health Implications. Journal of Xenobiotics. 2025; 15(6):197. https://doi.org/10.3390/jox15060197

Chicago/Turabian StyleRůžičková, Jana, Helena Raclavská, Marek Kucbel, Pavel Kantor, Barbora Švédová, and Karolina Slamová. 2025. "Indoor Airborne VOCs from Water-Based Coatings: Transfer Dynamics and Health Implications" Journal of Xenobiotics 15, no. 6: 197. https://doi.org/10.3390/jox15060197

APA StyleRůžičková, J., Raclavská, H., Kucbel, M., Kantor, P., Švédová, B., & Slamová, K. (2025). Indoor Airborne VOCs from Water-Based Coatings: Transfer Dynamics and Health Implications. Journal of Xenobiotics, 15(6), 197. https://doi.org/10.3390/jox15060197