Scientific and Regulatory Perspectives on Chemical Risk Assessment of Pesticides in the European Union

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Evidence and Regulation: State of the Art

3. Emerging Critical Issues in Risk Assessment

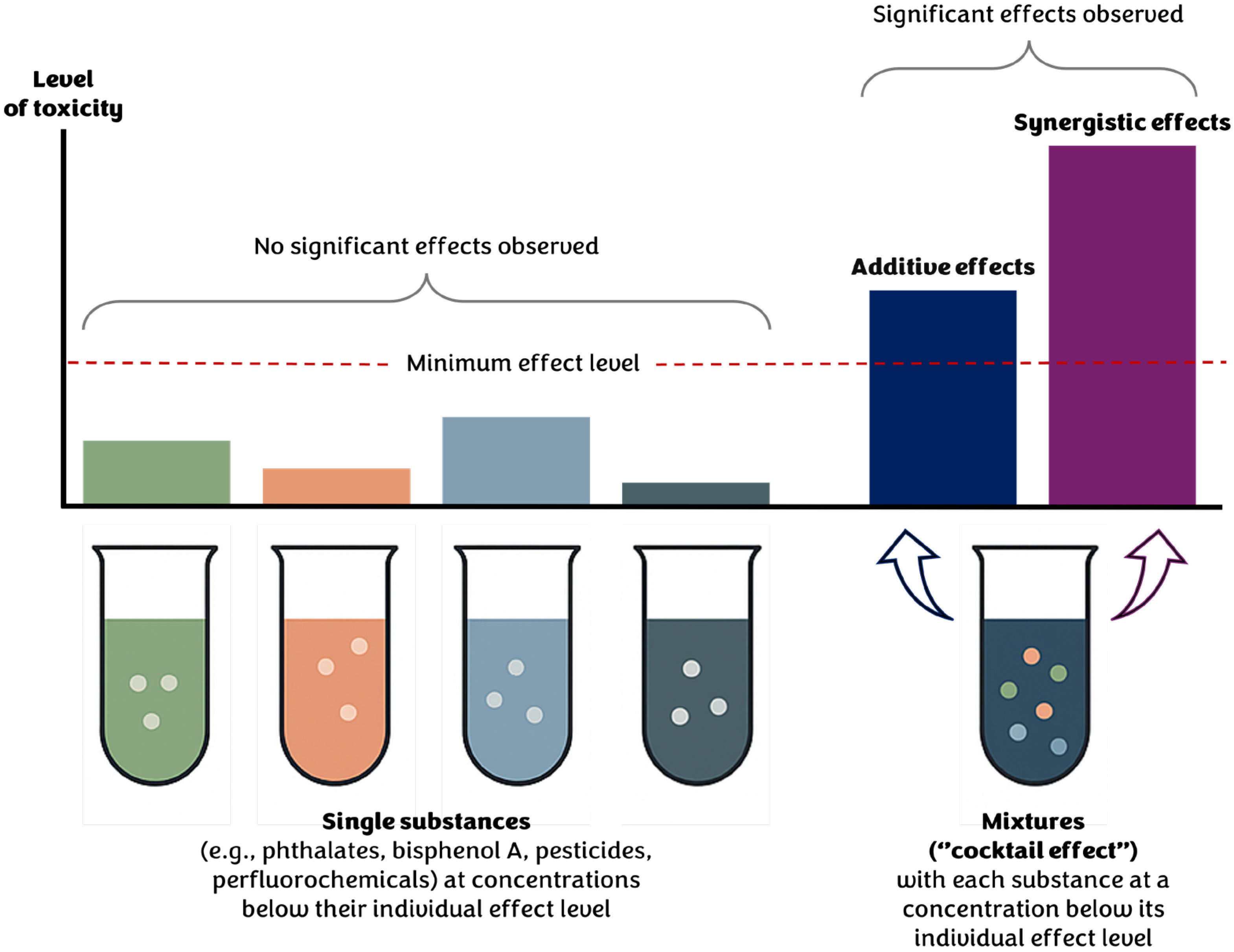

3.1. Cumulative Exposure and Chemical Mixtures

3.2. Low-Dose Effects and Non-Monotonic Dose–Response Curves

3.3. Environmental Persistence and Bioaccumulation Under Climate Change Scenarios

3.4. Endocrine Disruptors and Reprotoxicants

3.4.1. Evolving Regulatory Criteria and Implementation Gaps

| Active Substance | Chemical Class (Type) | Mechanism of Action in Human and Animals | Observed Effects | Category a | Regulatory Classification (EU) b | EU Status c |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Carbendazim | Benzimidazole (fungicide) | Inhibition of meiosis | Malformations and spermatogenesis toxicity [94] | Repr. 1B | ✔ Repr. 1B (CLP) + ✖ ED (not classified) | Not approved (Expiry: 30 November 2014) |

| Chlorpyrifos | Organophosphorus (insecticide) | Acetylcholinesterase inhibition, neuroendocrine alterations | Delayed brain development [95] | Suspected ED, Neurotoxic | ✖ ED (not classified) | Not approved (Expiry: 16 January 2020) |

| Epoxiconazole | Triazole (fungicide) | Aromatase inhibition | Fetal and developmental toxicity [96] | Repr. 1B, Repr. 2, suspected ED | ✔ Repr. 1B and 2 (CLP) + ✖ ED (not classified) | Not approved (Expiry: 30 April 2020) |

| Linuron | Phenylurea (herbicide) | Androgenic antagonism | Sexual development disorders [97] | Repr. 1B, Repr. 2, suspected ED | ✔ Repr. 1B and 2 (CLP) + ✖ ED (not classified) | Not approved (Expiry: 3 March 2017) |

| Mancozeb | Dithiocarbamate (fungicide) | Thyroid interference | Neurotoxicity, thyroid dysfunctions [98] | Repr. 1B, suspected ED | ✔ Repr. 1B (CLP) + ✖ ED (not classified) | Not approved (Expiry: 4 January 2021) |

| Prochloraz | Imidazole (fungicide) | Inhibition of steroidogenic enzymes | Testicular dysfunction, thyroid alterations [99] | Suspected Repr. 1B and ED | ✖ Repr. 1B and ED (not classified) | Not approved (Expiry: 31 December 2021) |

| Vinclozolin | Dicarboximide (fungicide) | Androgen receptor antagonism | Transgenerational effects [100] | Repr. 1B | ✔ Repr. 1B (CLP) + ✖ ED (not classified) | Banned |

3.4.2. Implications for Risk Assessment: Toward a Science-Based Paradigm Shift

4. Regulatory Implementation Proposals

- Retrospective re-evaluation of legacy substances: Substances approved before 2018, prior to the adoption of harmonized ED criteria, should undergo re-assessment under the updated scientific framework. This is essential to ensure consistency across the EU market and prevent the persistence of hazardous compounds based on outdated evaluations.

- Mandatory inclusion of ED-specific test guidelines: Regulatory submissions should require the systematic application of OECD testing guidelines specifically designed to detect endocrine and reproductive effects, such as Test Guidelines (TG) 440, 443, 456, and 458 [116,117,118,119]. These should be complemented by mechanistic and receptor-binding assays, where relevant.

- Modernized, transparent data systems: Platforms like OpenFoodTox, IUCLID, and the substance database of ECHA should be enhanced with standardized visual flags (e.g., ED, Repr. 1B, PMT), searchable endpoints, and dynamic links to scientific references. These improvements would allow regulators, researchers, and stakeholders to quickly access hazard classifications, support comparative assessments and substitution, and improve transparency for consumers.

- Regulatory harmonization across frameworks: Increased alignment is needed between Regulation (EC) No. 1107/2009 (plant protection products), REACH (industrial chemicals), and the CLP Regulation, particularly in terms of classification criteria, data requirements, hazard communication and workplace exposure. This would reduce redundancy, promote consistent decision-making, and avoid regulatory “blind spots” between sectors.

- A new hazard class is proposed for chemicals that have harmful effects on the immune system (immunotoxic substances), which would be incorporated into the CLP Regulation [7] to define their classification and labeling. In fact, various studies conducted in recent times showed that exposure to fungicides, herbicides, and insecticides is associated with an enormous number of diseases, including inflammatory diseases, rheumatoid arthritis, metabolic syndrome, cancer, respiratory diseases, nervous system diseases, and alteration in various organ systems [120,121]. These disorders are strongly associated with immunological dysfunction, one of the principle aims of the toxic activity of pesticides. Immuno-toxic substances, to which many pesticides belong, are capable of inhibiting innate and acquired immune functions, causing toxicity of varied severity to the organism. Tests conducted during the past few years on cells, animals, and human subjects have proved that pesticides substantially alter humoral and cell-mediated immunity [122,123,124]. These medications can specifically target single cells of the immune system, such as T lymphocytes, B lymphocytes, natural killer (NK) cells, and macrophages, inhibiting their survival, growth, and functional capability. Effects most frequently observed are apoptosis, or programmed cell death, cell cycle inhibition, DNA damage, and alteration of intracellular signal transduction mechanisms. On the molecular level, pesticides interfere with vital biological pathways and induce oxidative stress, mitochondrial injury, and endoplasmic reticulum stress [125,126]. These pathways lead to modifications of the expression of key factors like nuclear factor kappa B (NF-κB), pro-inflammatory cytokines including inter-leukin-6 (IL-6), interleukin-8 (IL-8), and interferon-gamma (IFN-γ), and anti-inflammatory mediators like interleukin-10 (IL-10) [127,128]. It has been noted that widely used or banned pesticides, like organophosphorus compounds (OPs), carbamates, pyrethroids, and other chemicals, have been associated with reduced antibody formation, inhibition of virus-induced B-cell differentiation into plasma cells, decreased T-lymphocyte proliferation, and repressed lytic activity of NK cells [120,121,129]. Certain pesticides have caused decreased phagocytosis, oxidative injury, and reorganization of cytokine production in macrophages that are essential for anti-viral and inflammatory function. These results, both in models and in studies of exposed populations, such as farmers, confirm the high immuno-toxic potential of pesticides. It has been observed that during peak agricultural seasons, B and T lymphocytes among workers exhibit higher levels of DNA damage than unexposed populations, posing a real risk to human health [130,131]. These immune system alterations can have long-term consequences, resulting in the onset of chronic diseases and increased susceptibility to infections, cancer, and inflammatory disorders. However, pesticide exposure can affect not only adults, particularly workers, but also children. Studies demonstrate an association between residential pesticide exposure in children and adolescents and the onset of leukemia, the most common pediatric cancer. In addition to leukemia, pesticide exposure increases the risk of non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma (NHL), amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, asthmatic events, type 2 diabetes, and neurodegenerative diseases such as Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s [128,132,133,134].On this basis, which adds to that about endocrine-disrupting and reprotoxic activities of some pesticides, it is a question of priority to improve new assessments based on immuno-toxicological markers, capable of identifying the risks early on and guiding the use of more restrictive regulation for pesticide use. At the same time, efforts must be made to encourage the development of less hazardous substitutes and integrated control methods in a manner that will protect public health without jeopardizing agricultural production.

5. Future Scientific Directions: Predictive Toxicology and Innovative Approaches

5.1. Human Biomonitoring and Real-World Exposure

5.2. Alternative Models and Advanced Technologies

5.3. Regulatory Review and the Precautionary Principle

6. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Correction Statement

References

- Pretty, J.; Bharucha, Z.P. Integrated pest management for sustainable intensification of agriculture in Asia and Africa. Insects 2015, 6, 152–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mostafalou, S.; Abdollahi, M. Pesticides and human chronic diseases: Evidences, mechanisms, and perspectives. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 2013, 268, 157–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silva, E.; Rajapakse, N.; Kortenkamp, A. Something from “nothing”—Eight weak estrogenic chemicals combined at concentrations below NOECs produce significant mixture effects. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2019, 36, 1751–1756. [Google Scholar]

- European Food Safety Authority (EFSA); Carrasco Cabrera, L.; Pastor, P.M. The 2019 European Union report on pesticide residues in food. EFSA J. 2021, 19, e06491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Consolidated Text: Regulation (EC) No 1107/2009 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 21 October 2009 Concerning the Placing of Plant Protection Products on the Market and Repealing Council Directives 79/117/EEC and 91/414/EEC. Available online: http://data.europa.eu/eli/reg/2009/1107/2022-11-21 (accessed on 3 April 2025).

- Consolidated Text: Regulation (EC) No 1907/2006 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 18 December 2006 Concerning the Registration, Evaluation, Authorisation and Restriction of Chemicals (REACH), Establishing a European Chemicals Agency, Amending Directive 1999/45/EC and Repealing Council Regulation (EEC) No 793/93 and Commission Regulation (EC) No 1488/94 as Well as Council Directive 76/769/EEC and Commission Directives 91/155/EEC, 93/67/EEC, 93/105/EC and 2000/21/EC (Text with EEA Relevance). Available online: http://data.europa.eu/eli/reg/2006/1907/2024-12-18 (accessed on 3 April 2025).

- Consolidated Text: Regulation (EC) No 1272/2008 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 16 December 2008 on Classification, Labelling and Packaging of Substances and Mixtures, Amending and Repealing Directives 67/548/EEC and 1999/45/EC, and Amending Regulation (EC) No 1907/2006 (Text with EEA Relevance). Available online: http://data.europa.eu/eli/reg/2008/1272/2025-02-01 (accessed on 3 April 2025).

- European Commission. Chemicals Strategy for Sustainability Towards a Toxic-Free Environment. COM(2020)667 Final. 2020. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=celex:52020DC0667 (accessed on 3 April 2025).

- Vandenberg, L.N.; Colborn, T.; Hayes, T.B.; Heindel, J.J.; Jacobs, D.R.; Lee, D.H.; Shioda, T.; Soto, A.M.; vom Saal, F.S.; Welshons, W.V.; et al. Hormones and endocrine-disrupting chemicals: Low-dose effects and nonmonotonic dose responses. Endocr. Rev. 2012, 33, 378–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvalho, F.P. Pesticides, environment, and food safety. Food Energy Secur. 2017, 6, 48–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergman, Å.; Heindel, J.J.; Jobling, S.; Kidd, K.A.; Zoeller, R.T.; Endocrine Disrupting Chemicals-2012. Geneva: United Nations Environment Programme and the World Health Organization 2013. Available online: https://iris.who.int/bitstream/handle/10665/78102/WHO_HSE_PHE_IHE_2013.1_eng.pdf (accessed on 3 April 2025).

- La Merrill, M.A.; Vandenberg, L.N.; Smith, M.T.; Goodson, W.; Browne, P.; Patisaul, H.B.; Guyton, K.Z.; Kortenkamp, A.; Cogliano, V.J.; Woodruff, T.J.; et al. Consensus on the key characteristics of endocrine-disrupting chemicals as a basis for hazard identification. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 2020, 16, 45–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Transparency International EU & PAN Europe. Emergency Authorisations and Pesticide Regulation in the EU. 2023. Available online: https://www.pan-europe.info/resources/reports/2023/01/banned-pesticides-still-use-eu?utm_source=chatgpt.com (accessed on 3 April 2025).

- Carisio, L.; Delso, N.S.; Tosi, S. Beyond the urgency: Pesticide Emergency Authorisations’ exposure, toxicity, and risk for humans, bees, and the environment. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 947, 174217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EFSA (European Food Safety Authority); Carrasco Cabrera, L.; Di Piazza, G.; Dujardin, B.; Marchese, E.; Medina Pastor, P. The 2022 European Union report on pesticide residues in food. EFSA J. 2024, 22, e8753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, M.; Wang, Y.; Yang, G.; Wang, Y.; Liu, F.; Chen, C. A review of cumulative risk assessment of multiple pesticide residues in food: Current status, approaches and future perspectives. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2024, 144, 104340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EFSA (European Food Safety Authority); Carrasco Cabrera, L.; Di Piazza, G.; Dujardin, B.; Medina Pastor, P. The 2021 European Union report on pesticide residues in food. EFSA J. 2023, 21, e07939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Z.; Wang, D.; Zhu, T.; Tao, Y.; Ni, C. Review of deep learning-based methods for non-destructive evaluation of agricultural products. Biosyst. Eng. 2024, 245, 56–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dedeoglu, V.; Malik, S.; Ramachandran, G.; Pal, S.; Jurdak, R. Chapter Nine—Blockchain meets edge-AI for food supply chain traceability and provenance. In Comprehensive Analytical Chemistry; Nelis, J.L.D., Tsagkaris, A.S., Eds.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2023; Volume 101, pp. 251–275. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, M.W.H.; Goodman, J.M.; Allen, T.E.H. Machine learning in predictive toxicology: Recent applications and future directions for classification models. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 2020, 34, 217–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Commission Regulation (EU) 2022/1438 of 31 August 2022 Amending Annex II to Regulation (EC) No 1107/2009 of the European Parliament and of the Council as Regards Specific Criteria for the Approval of Active Substances That Are Micro-Organisms. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:32022R1438 (accessed on 22 September 2025).

- European Commission. Procedure to Apply for Authorisation of a PPP. Available online: https://food.ec.europa.eu/plants/pesticides/authorisation-plant-protection-products/ppp-auth_en (accessed on 20 September 2025).

- Consolidated Text: Commission Regulation (EU) No 283/2013 of 1 March 2013 Setting Out the Data Requirements for Active Substances, in Accordance with Regulation (EC) No 1107/2009 of the European Parliament and of the Council Concerning the Placing of Plant Protection Products on the Market. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:02013R0283-20221121&qid=1758704708346 (accessed on 22 September 2025).

- Consolidated Text: Commission Regulation (EU) No 284/2013 of 1 March 2013 Setting Out the Data Requirements for Plant Protection Products, in Accordance with Regulation (EC) No 1107/2009 of the European Parliament and of the Council Concerning the Placing of Plant Protection Products on the Market. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:02013R0284-20221121&qid=1758704783082 (accessed on 22 September 2025).

- Commission Regulation (EU) 2022/1439 of 31 August 2022 Amending Regulation (EU) No 283/2013 as Regards the Information to Be Submitted for Active Substances and the Specific Data Requirements for Micro-Organisms. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:32022R1439 (accessed on 22 September 2025).

- Commission Regulation (EU) 2022/1440 of 31 August 2022 Amending Regulation (EU) No 284/2013 as Regards the Information to Be Submitted for Plant Protection Products and the Specific Data Requirements for Plant Protection Products Containing Micro-Organisms. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:32022R1440&qid=1758704962525 (accessed on 22 September 2025).

- Consolidated Text: Commission Regulation (EU) No 546/2011 of 10 June 2011 Implementing Regulation (EC) No 1107/2009 of the European Parliament and of the Council as Regards Uniform Principles for Evaluation and Authorisation of Plant Protection Products. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:02011R0546-20221121&qid=1758705109929 (accessed on 22 September 2025).

- Commission Regulation (EU) 2022/1441 of 31 August 2022 Amending Regulation (EU) No 546/2011 as Regards Specific Uniform Principles for Evaluation and Authorisation of Plant Protection Products Containing Micro-Organisms. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:32022R1441&qid=1758705216629 (accessed on 22 September 2025).

- European Commission. Approval of Active Substances, Safeners and Synergists. Available online: https://food.ec.europa.eu/plants/pesticides/approval-active-substances-safeners-and-synergists_en (accessed on 22 September 2025).

- European Chemicals Agency (ECHA), IUCLID 6. Available online: https://iuclid6.echa.europa.eu/ (accessed on 22 September 2025).

- Consolidated Text: Regulation (EC) No 178/2002 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 28 January 2002 Laying Down the General Principles and Requirements of Food Law, Establishing the European Food Safety Authority and Laying Down Procedures in Matters of Food Safety. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:02002R0178-20240701 (accessed on 22 September 2025).

- Consolidated Text: Regulation (EC) No 396/2005 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 23 February 2005 on Maximum Residue Levels of Pesticides in or on Food and Feed of Plant and Animal Origin and Amending Council Directive 91/414/EEC. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:02005R0396-20250512 (accessed on 22 September 2025).

- Barbieri, M.V.; Monllor-Alcaraz, L.S.; Postigo, C.; López de Alda, M. Improved fully automated method for the determination of medium to highly polar pesticides in surface and groundwater and application in two distinct agriculture-impacted areas. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 745, 140650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shiva, S.; Hofman, K. A worldwide review of currently used pesticides’ monitoring in agricultural soils. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 812, 152344. [Google Scholar]

- Hussari, M.N.; Chronister, B.N.C.; Yang, K.; Tu, X.; Martinez, D.; Parajuli, R.P.; Suarez-Torres, J.; Boyd Barr, D.; Hong, S.; Suarez-Lopez, J.R. Associations Between Urinary Pesticide Metabolites and Serum Inflammatory Biomarkers in Adolescents Living in an Agricultural Region. Expo. Health 2025, 17, 887–904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mostafalou, S.; Abdollahi, M. Pesticides: An update of human exposure and toxicity. Arch. Toxicol. 2017, 91, 549–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, L.; Abd El-Aty, A.M.; Eun, J.B.; Shim, J.H.; Zhao, J.; Lei, X.; Gao, S.; She, Y.; Jin, F.; Wang, J.; et al. Recent advances in rapid detection techniques for pesticide residue: A review. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2022, 70, 13093–13117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esbaugh, A.J.; Khursigara, A.; Johansen, J. Toxicity in Aquatic Environments: The Cocktail Effect. In Development and Environment; Burggren, W., Dubansky, B., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Gomez-Gimenez, B.; Llansola, M.; Cabrera-Pastor, A.; Hernandez-Rabaza, V.; Agusti, A.; Felipo, V. Endosulfan and cypermethrin pesticide mixture induces synergistic or antagonistic effects on developmental exposed rats depending on the analyzed behavioral or neurochemical end points. ACS Chem. Neurosci. 2018, 9, 369–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gordon, C.J.; Herr, D.W.; Gennings, C.; Graff, J.E.; McMurray, M.; Stork, L.; Coffey, T.; Hamm, A.; Mack, C.M. Thermoregulatory response to an organophosphate and carbamate insecticide mixture: Testing the assumption of dose-additivity. Toxicology 2006, 217, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Food Safety Authority (EFSA); Crivellente, F.; Hernández-Jerez, A.F.; Lanzoni, A.; Metruccio, F.; Mohimont, L.; Nikolopoulou, D.; Castoldi, A.F. Specific effects on the thyroid relevant for performing a dietary cumulative risk assessment of pesticide residues: 2024 update. EFSA J. 2024, 22, e8672. [Google Scholar]

- Metruccio, F.; Castelli, I.; Baroni, A.; Marazzini, M.; Mammone, T.; Tosti, L. Data collection, hazard characterisation and establishment of cumulative assessment groups of pesticides for specific effects on the thyroid: 2024 update. EFSA Support. Publ. 2024, 21, 9012E. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Chemicals Agency (ECHA) 2023. Annual Report 2022. Available online: https://echa.europa.eu/annual-report-2022 (accessed on 3 April 2025).

- Commission Delegated Regulation (EU) 2023/707 of 19 December 2022 Amending Regulation (EC) No 1272/2008 as Regards Hazard Classes and Criteria for the Classification, Labelling and Packaging of Substances and Mixtures (Text with EEA Relevance). Available online: http://data.europa.eu/eli/reg_del/2023/707/oj (accessed on 3 April 2025).

- Backhaus, T. Exploring the mixture assessment or allocation factor (MAF): A brief overview of the current discourse. Curr. Opin. Toxicol. 2024, 37, 100460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Treu, G.; Schulze, J.; Galert, W.; Hassold, E. Regulatory and practical considerations on the implementation of a mixture allocation factor in REACH. Environ. Sci. Eur. 2024, 36, 101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Environmental Protection Agency (EPA)—Pesticide Environmental Stewardship Program (PESP). Available online: https://www.epa.gov/pesp (accessed on 19 July 2025).

- Environmental Protection Agency (EPA)—Endocrine Disruptor Screening Program (EDSP). Available online: https://www.epa.gov/endocrine-disruption (accessed on 19 July 2025).

- Pest Management Regulatory Agency (PMRA)—Pest Control Products (Pesticides) Acts and Regulations. Available online: https://www.canada.ca/en/health-canada/services/consumer-product-safety/pesticides-pest-management/public/protecting-your-health-environment/pest-control-products-acts-and-regulations-en.html (accessed on 20 July 2025).

- Chintada, V.; Veraiah, K.; Golla, N. Monitoring and Managing Endocrine Disrupter Pesticides (EPDS) for Environmental Sustainability. In Biotechnology for Environmental Sustainability; Interdisciplinary Biotechnological Advances; Verma, P., Ed.; Springer: Singapore, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Environmental Protection Agency (EPA)—Overview of Risk Assessment in the Pesticide Program. Available online: https://www.epa.gov/pesticide-science-and-assessing-pesticide-risks/overview-risk-assessment-pesticide-program (accessed on 22 August 2025).

- EFSA (European Food Safety Authority); Charistou, A.; Coja, T.; Craig, P.; Hamey, P.; Martin, S.; Sanvido, O.; Chiusolo, A.; Colas, M.; Istace, F. Guidance on the assessment of exposure of operators, workers, residents and bystanders in risk assessment of plant protection products. EFSA J. 2022, 20, e07032. [Google Scholar]

- Zaller, J.G. What is the problem? Pesticides in our everyday life. In Daily Poison: Pesticides—An Underestimated Danger; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 1–125. [Google Scholar]

- Orton, F.; Ermler, S.; Kugathas, S.; Rosivatz, E.; Scholze, M.; Kortenkamp, A. Mixture effects at very low doses with combinations of anti-androgenic pesticides, antioxidants, industrial pollutant and chemicals used in personal care products. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 2014, 278, 201–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EFSA Panel on Plant Protection Products and their Residues (PPR). Scientific Opinion on the identification of pesticides to be included in cumulative assessment groups on the basis of their toxicological profile (2014 update). EFSA J. 2013, 11, 3293. [Google Scholar]

- Beausoleil, C.; Beronius, A.; Bodin, L.; Bokkers, B.G.H.; Boon, P.E.; Burger, M.; Cao, Y.; De Wit, L.; Fischer, A.; Hanberg, A.; et al. Review of non-monotonic dose-responses of substances for human risk assessment. EFSA Support. Publ. 2016, 13, 1027E. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EFSA Scientific Committee; More, S.; Benford, D.; Hougaard Bennekou, S.; Bampidis, V.; Bragard, C.; Halldorsson, T.; Hernandez-Jerez, A.; Koutsoumanis, K.; Lambré, C.; et al. Opinion on the impact of non-monotonic dose responses on EFSA′s human health risk assessments. EFSA J. 2021, 19, e06877. [Google Scholar]

- McMahon, T.A.; Romansic, J.M.; Rohr, J.R. Nonmonotonic and monotonic effects of pesticides on the pathogenic fungus Batrachochytrium dendrobatidis in culture and on tadpoles. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2013, 47, 7958–7964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skinner, M.K. Endocrine disruptor induction of epigenetic transgenerational inheritance of disease. Mol. Cell. Endocrinol. 2014, 398, 4–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simms, A.; Robert, K.; Spencer, R.J.; Treby, S.; Williams-Kelly, K.; Sexton, C.; Korossy-Horwood, R.; Terry, R.; Parker, A.; Van Dyke, J. A systematic review of how endocrine-disrupting contaminants are sampled in environmental compartments: Wildlife impacts are overshadowed by environmental surveillance. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2025, 32, 8670–8678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vischetti, C.; Casucci, C.; De Bernardi, A.; Monaci, E.; Tiano, L.; Marcheggiani, F.; Ciani, M.; Comitini, F.; Marini, E.; Taskin, E.; et al. Sub-Lethal Effects of Pesticides on the DNA of Soil Organisms as Early Ecotoxicological Biomarkers. Front. Microbiol. 2020, 11, 1892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomes, I.B. The overlooked interaction of emerging contaminants and microbial communities: A threat to ecosystems and public health. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2025, 136, lxaf064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hooper, M.J.; Ankley, G.T.; Cristol, D.A.; Maryoung, L.A.; Noyes, P.D.; Kent, E. PinkertonInteractions between chemical and climate stressors: A role for mechanistic toxicology in assessing climate change risks. Environ. Toxicol. Chem. 2013, 32, 32–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Delnat, V.; Tran, T.T.; Verheyen, J.; Van Dinh, K.; Janssens, L.; Stoks, R. Temperature variation magnifies chlorpyrifos toxicity differently between larval and adult mosquitoes. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 690, 1237–1244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Hou, J.; Deng, R. Co-exposure of environmental contaminants with unfavorable temperature or humidity/moisture: Joint hazards and underlying mechanisms. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2023, 264, 115432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, W.; Chen, C.; Yang, L.; Chen, Z.; Zhu, L.; Zhu, L.; Feng, J. Chemical Ecological Risk Assessment for Aquatic Life Under Climate Change: A Review from Occurrence, Bioaccumulation, and Toxicity Perspective. Rev. Environ. Contam. Toxicol. 2025, 263, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khatib, I.; Rychter, P.; Falfushynska, H. Pesticide Pollution: Detrimental Outcomes and Possible Mechanisms of Fish Exposure to Common Organophosphates and Triazines. J. Xenobiot. 2022, 12, 236–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossi, A.S.; Fantón, N.; Michlig, M.P.; Repetti, M.R.; Cazenave, J. Fish inhabiting rice fields: Bioaccumulation, oxidative stress and neurotoxic effects after pesticides application. Ecol. Indic. 2020, 113, 106186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schönhart, M.; Schmid, E.; Schneider, U.A. CropRota—A crop rotation model to support integrated land use assessments. Eur. J. Agron. 2011, 34, 263–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasche, L. Estimating Pesticide Inputs and Yield Outputs of Conventional and Organic Agricultural Systems in Europe under Climate Change. Agronomy 2021, 11, 1300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mnif, W.; Hassine, A.I.H.; Bouaziz, A.; Bartegi, A.; Thomas, O.; Roig, B. Effect of Endocrine Disruptor Pesticides: A Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2011, 8, 2265–2303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallo, A. Reprotoxic Impact of Environment, Diet, and Behavior. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 1303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Consolidated Text: Commission Regulation (EU) 2018/605 of 19 April 2018 Amending Annex II to Regulation (EC) No 1107/2009 by Setting Out Scientific Criteria for the Determination of Endocrine Disrupting Properties (Text with EEA Relevance). Available online: http://data.europa.eu/eli/reg/2018/605/2018-04-20 (accessed on 3 April 2025).

- Colborn, T.; Vom Saal, F.S.; Soto, A.M. Developmental effects of endocrine-disrupting chemicals in wildlife and humans. Environ. Health Perspect. 1993, 101, 378–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colborn, T. Neurodevelopment and endocrine disruption. Environ. Health Perspect. 2004, 112, 944–949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Endocrine Disruptor List. Available online: https://edlists.org/the-ed-lists (accessed on 21 August 2025).

- EFSA (European Food Safety Authority); Álvarez, F.; Arena, M.; Auteri, D.; Leite, S.B.; Binaglia, M.; Castoldi, A.F.; Chiusolo, A.; Colagiorgi, A.; Colas, M.; et al. Peer review of the pesticide risk assessment of the active substance fludioxonil. EFSA J. 2024, 22, e9047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EFSA (European Food Safety Authority); Álvarez, F.; Arena, M.; Auteri, D.; Leite, S.B.; Binaglia, M.; Castoldi, A.F.; Chiusolo, A.; Colagiorgi, A.; Colas, M.; et al. Peer review of the pesticide risk assessment of the active substance flufenacet. EFSA J. 2024, 22, e8997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dias, G.R.M.; Giusti, F.C.V.; de Novais, C.O.; de Oliveira, M.A.L.; Paiva, A.G.; Kalil-Cutti, B.; Mahoney, M.M.; Graceli, J.B. Intergenerational and transgenerational effects of endocrine-disrupting chemicals in the offspring brain development and behavior. Front. Endocrinol. 2025, 16, 1571689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eaton, D.L.; Daroff, R.B.; Autrup, H.; Bridges, J.; Buffler, P.; Costa, L.G.; Coyle, J.; McKhann, G.; Mobley, W.C.; Nadel, L.; et al. Review of the Toxicology of Chlorpyrifos With an Emphasis on Human Exposure and Neurodevelopment. Crit. Rev. Toxicol. 2008, 38 (Suppl. S2), 1–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, H.; Zheng, W.; Han, H.; Hu, X.; Hu, B.; Wang, G.; Su, L.; Li, H.; Li, Y. Reproductive toxicity of linuron following gestational exposure in rats and underlying mechanisms. Toxicol. Lett. 2017, 266, 49–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patisaul, H.B.; Adewale, H.B. Long-term effects of environmental endocrine disruptors on reproductive physiology and behavior. Front. Behav. Neurosci. 2009, 3, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heindel, J.; Newbold, R.; Schug, T. Endocrine disruptors and obesity. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 2015, 11, 653–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Commission Delegated Regulation (EU) 2017/2100 of 4 September 2017 Setting Out Scientific Criteria for the Determination of Endocrine-Disrupting Properties Pursuant to Regulation (EU) No 528/2012 of the European Parliament and Council (Text with EEA Relevance). Available online: http://data.europa.eu/eli/reg_del/2017/2100/oj (accessed on 3 April 2025).

- Solecki, R.; Kortenkamp, A.; Bergman, Å.; Chahoud, I.; Degen, G.H.; Dietrich, D.; Greim, H.; Håkansson, H.; Hass, U.; Husoy, T.; et al. Scientific principles for the identification of endocrine-disrupting chemicals: A consensus statement. Arch. Toxicol. 2017, 91, 1001–1006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kättström, D.; Beronius, A.; Boije af Gennäs, U.; Rudén, C.; Ågerstrand, M. Impact of the new hazard classes in the CLP regulation on EU chemicals legislation. Env. Sci. Eur. 2025, 37, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EFSA (European Food Safety Authority). Peer review of the pesticide risk assessment for the active substance epoxiconazole in light of confirmatory data submitted. EFSA J. 2015, 13, 4123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EFSA (European Food Safety Authority). Peer review of the pesticide risk assessment of the active substance linuron. EFSA J. 2016, 14, 4518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EFSA (European Food Safety Authority); Bellisai, G.; Bernasconi, G.; Binaglia, M.; Carrasco Cabrera, L.; Castellan, I.; Castoldi, A.F.; Chiusolo, A.; Crivellente, F.; Del Aguila, M.; et al. Updated reasoned opinion on the toxicological properties and maximum residue levels (MRLs) for the benzimidazole substances carbendazim and thiophanate-methyl. EFSA J. 2024, 22, e8569. [Google Scholar]

- Council Decision (EU) 2021/592 of 7 April 2021 on the Submission, on Behalf of the European Union, of a Proposal for the Listing of Chlorpyrifos in Annex A to the Stockholm Convention on Persistent Organic Pollutants. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/HTML/?uri=CELEX:32021D0592 (accessed on 18 July 2025).

- Stockholm Convention on Persistent Organic Pollutants (POPs). Available online: https://www.pops.int/TheConvention/ThePOPs/AllPOPs/tabid/2509/Default.aspx (accessed on 11 October 2025).

- Commission Implementing Regulation (EU) 2020/18 of 10 January 2020 Concerning the Non-Renewal of the Approval of the Active Substance Chlorpyrifos, in Accordance with Regulation (EC) No 1107/2009 of the European Parliament and of the Council Concerning the Placing of Plant Protection Products on the Market, and Amending the Annex to Commission Implementing Regulation (EU) No 540/2011. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/HTML/?uri=CELEX:32020R0018 (accessed on 11 October 2025).

- EFSA (European Food Safety Authority). Statement on the available outcomes of the human health assessment in the context of the pesticides peer review of the active substance chlorpyrifos. EFSA J. 2019, 17, e05809. [Google Scholar]

- Rama, E.M.; Bortolan, S.; Vieira, M.L.; Gerardin, D.C.C.; Moreira, E.G. Reproductive and possible hormonal effects of carbendazim. Regul. Toxicol. Pharmacol. 2014, 69, 476–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ur Rahman, H.U.; Asghar, W.; Nazir, W.; Sandhu, M.A.; Ahmed, A.; Khalid, N. A comprehensive review on chlorpyrifos toxicity with special reference to endocrine disruption: Evidence of mechanisms, exposures and mitigation strategies. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 755, 142649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Wang, F.; Li, L.; Fan, B.; Kong, Z.; Tan, J.; Li, M. The potential endocrine-disrupting of fluorinated pesticides and molecular mechanism of EDPs in cell models. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2025, 289, 117615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.; Pedersen, M.; Vinggaard, A.M. In vitro antiandrogenic effects of the herbicide linuron and its metabolites. Chemosphere 2024, 349, 140773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norouzi, F.; Alizadeh, I.; Faraji, M. Human exposure to pesticides and thyroid cancer: A worldwide systematic review of the literatures. Thyroid. Res. 2023, 16, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blystone, C.R.; Lambritth, C.S.; Howdeshell, K.L.; Furr, J.; Sternberg, R.M.; Butterworth, B.C.; Durhan, E.J.; Makynen, E.A.; Ankley, G.T.; Wilson, V.S.; et al. Sensitivity of fetal rat testicular steroidogenesis to maternal prochloraz exposure and the underlying mechanism of inhibition. Toxicol. Sci. 2007, 97, 512–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rizzo, R.; Bortolotti, D.; Rizzo, S.; Schiuma, G. Endocrine disruptors, epigenetic changes, and transgenerational transmission. In Environment Impact on Reproductive Health; Robert, M., Ed.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2023; pp. 49–74. [Google Scholar]

- EFSA (European Food Safety Authority). Targeted risk assessment for prochloraz. EFSA J. 2023, 21, e08231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- EFSA (European Food Safety Authority); Abdourahime, H.; Anastassiadou, M.; Arena, M.; Auteri, D.; Barmaz, S.; Brancato, A.; Bura, L.; Carrasco Cabrera, L.; Chaideftou, E.; et al. Peer review of the pesticide risk assessment of the active substance mancozeb. EFSA J. 2020, 18, e05755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Commission Implementing Regulation (EU) 2018/113 of 24 January 2018 Renewing the Approval of the Active Substance Acetamiprid in Accordance with Regulation (EC) No 1107/2009 of the European Parliament and of the Council Concerning the Placing of Plant Protection Products on the Market, and Amending the Annex to Commission Implementing Regulation (EU) No 540/2011. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=OJ:L:2018:020:TOC (accessed on 8 October 2025).

- EFSA PPR Panel (EFSA Panel on Plant Protection Products and their Residues); Hernandez Jerez, A.; Adriaanse, P.; Berny, P.; Coja, T.; Duquesne, S.; Focks, A.; Marinovich, M.; Millet, M.; Pelkonen, O.; et al. Statement on the active substance acetamiprid. EFSA J. 2022, 20, e07031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EFSA (European Food Safety Authority); Hernandez-Jerez, A.; Coja, T.; Paparella, M.; Price, A.; Henri, J.; Focks, A.; Louisse, J.; Terron, A.; Binaglia, M.; et al. Statement on the toxicological properties and maximum residue levels of acetamiprid and its metabolites. EFSA J. 2024, 22, e8759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Standing Committee on Plants, Animals, Food and Feed Section Phytopharmaceuticals—Legislation 4–5 December 2024. Summary Report. Available online: https://food.ec.europa.eu/document/download/bbbd95c0-c323-4a91-a534-4d496f280db2_en?filename=sc_phyto_20241204002_ppl_sum.pdf (accessed on 8 October 2025).

- EFSA (European Food Safety Authority). Statement on the testing strategy and timelines for the assessment of developmental neurotoxicity and endocrine disruption properties of acetamiprid in the context of the review of the approval of the active substance. EFSA J. 2025, 23, e9639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colopi, A.; Guida, E.; Cacciotti, S.; Fuda, S.; Lampitto, M.; Onorato, A.; Zucchi, A.; Balistreri, C.R.; Grimaldi, P.; Barchi, M. Dietary Exposure to Pesticide and Veterinary Drug Residues and Their Effects on Human Fertility and Embryo Development: A Global Overview. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 9116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robaire, B.; Delbes, G.; Head, J.A.; Marlatt, V.L.; Martyniuk, C.J.; Reynaud, S.; Trudeau, V.L.; Mennigen, J.A. A cross-species comparative approach to assessing multi- and transgenerational effects of endocrine disrupting chemicals. Environ. Res. 2022, 204 Pt B, 112063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thorson, J.L.M.; Beck, D.; Ben Maamar, M.; Nilsson, E.E.; Skinner, M.K. Epigenome-wide association study for pesticide (Permethrin and DEET) induced DNA methylation epimutation biomarkers for specific transgenerational disease. Environ. Health 2020, 19, 109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karlsson, O.; Svanholm, S.; Eriksson, A.; Chidiac, J.; Eriksson, J.; Jernerén, F.; Berg, C. Pesticide-induced multigenerational effects on amphibian reproduction and metabolism. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 775, 145771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, C.; He, K.; Li, H.; Zhang, L.; Mao, L.; Zhu, L.; Jiang, J.; Liu, X. Transgenerational combined toxicity effects of neonicotinoids and triazole pesticides at environmentally relevant concentrations on D. magna: From individual to population level. J. Hazard. Mater. 2025, 486, 137023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stone, A.M.; Camp, O.G.; Biernat, M.M.; Bai, D.; Awonuga, A.O.; Abu-Soud, H.M. Re-Evaluating the Use of Glyphosate-based Herbicides: Implications on Fertility. Reprod. Sci. 2025, 32, 950–964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, C.; Schilirò, T.; Gea, M.; Bianchi, S.; Spinello, A.; Magistrato, A.; Gilardi, G.; Di Nardo, G. Molecular Basis for Endocrine Disruption by Pesticides Targeting Aromatase and Estrogen Receptor. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 5664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, X.; Huang, Q. Environmental pollutants exposure and male reproductive toxicity: The role of epigenetic modifications. Toxicology 2021, 456, 152780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- OECD. Test No. 440: Uterotrophic Bioassay in Rodents: A short-term screening test for oestrogenic properties. In OECD Guidelines for the Testing of Chemicals; Section 4; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- OECD. Test No. 443: Extended One-Generation Reproductive Toxicity Study. In OECD Guidelines for the Testing of Chemicals; Section 4; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- OECD. Test No. 456: H295R Steroidogenesis Assay. In OECD Guidelines for the Testing of Chemicals; Section 4; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- OECD. Test No. 458: Stably Transfected Human Androgen Receptor Transcriptional Activation Assay for Detection of Androgenic Agonist and Antagonist Activity of Chemicals. In OECD Guidelines for the Testing of Chemicals; Section 4; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Cestonaro, L.V.; Macedo, S.M.D.; Piton, Y.V.; Garcia, S.C.; Arbo, M.D. Toxic effects of pesticides on cellular and humoral immunity: An overview. Immunopharmacol. Immunotoxicol. 2022, 44, 816–831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, G.-H.; Choi, K.-C. Adverse effects of pesticides on the functions of immune system. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. Part C Toxicol. Pharmacol. 2020, 235, 108789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Naidenko, O.V.; Andrews, D.Q.; Temkin, A.M.; Stoiber, T.; Uche, U.I.; Evans, S.; Perrone-Gray, S. Investigating molecular mechanisms of immunotoxicity and the utility of ToxCast for immunotoxicity screening of chemicals added to food. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 3332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casida, J.E.; Durkin, K.A. Pesticide chemical research in toxicology: Lessons from nature. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 2017, 30, 94–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corsini, E.; Sokooti, M.; Galli, C.L.; Moretto, A.; Colosio, C. Pesticide induced immunotoxicity in humans: A comprehensive review of the existing evidence. Toxicology 2013, 307, 123–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, B.; Zhang, H.; Jia, K.; Li, E.; Zhang, S.; Yu, H.; Cao, Z.; Xiong, G.; Hu, C.; Lu, H. Effects of spinetoram on the developmental toxicity and immunotoxicity of zebrafish. Fish Shellfish Immunol. 2020, 96, 114–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, J.; Wu, S.; Wang, Y.; An, X.; Cai, L.; Zhao, X.; Wu, C. Carbendazim has the potential to induce oxidative stress, apoptosis, immunotoxicity and endocrine disruption during zebrafish larvae development. Toxicol. Vitr. 2015, 29, 1473–1481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weis, G.C.C.; Assmann, C.E.; Cadona, F.C.; Bonadiman, B.D.S.R.; de Oliveira Alves, A.; Machado, A.K.; Duarte, M.M.M.F.; da Cruz, I.B.M.; Costabeber, I.H. Immunomodulatory effect of mancozeb, chlorothalonil, and thiophanate methyl pesticides on macrophage cells. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2019, 182, 109420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, T.J.; Gabure, S.; Maise, J.; Snipes, S.; Peete, M.; Whalen, M.M. The organochlorine pesticides pentachlorophenol and dichlorodiphenyltrichloroethane increase secretion and production of interleukin 6 by human immune cells. Environ. Toxicol. Pharmacol. 2019, 72, 103263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mokarizadeh, A.; Faryabi, M.R.; Rezvanfar, M.A.; Abdollahi, M. A comprehensive review of pesticides and the immune dysregulation: Mechanisms, evidence and consequences. Toxicol. Mech. Methods 2015, 25, 258–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alam, R.T.; Imam, T.S.; Abo-Elmaaty, A.M.; Arisha, A.H. Amelioration of fenitrothion induced oxidative DNA damage and inactivation of caspase-3 in the brain and spleen tissues of male rats by N-acetylcysteine. Life Sci. 2019, 231, 116534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lone, M.I.; Nabi, A.; Dar, N.J.; Hussain, A.; Nazam, N.; Hamid, A.; Ahmad, W. Toxicogenetic evaluation of dichlorophene in peripheral blood and in the cells of the immune system using molecular and flow cytometric approaches. Chemosphere 2017, 167, 520–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Maele-Fabry, G.; Gamet-Payrastre, L.; Lison, D. Household exposure to pesticides and risk of leukemia in children and adolescents: Updated systematic review and meta-analysis. Int. J. Hyg. Environ. Health 2019, 222, 49–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, D.; Zhou, T.; Tao, Y.; Feng, Y.; Shen, X.; Mei, S. Exposure to organochlorine pesticides and non-Hodgkin lymphoma: A meta-analysis of observational studies. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 25768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falzone, L.; Marconi, A.; Loreto, C.; Franco, S.; Spandidos, D.A.; Libra, M. Occupational exposure to carcinogens: Benzene, pesticides and fibers. Mol. Med. Rep. 2016, 14, 4467–4474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD. Adverse Outcome Pathways. Available online: https://www.oecd.org/en/topics/sub-issues/testing-of-chemicals/adverse-outcome-pathways.html (accessed on 20 September 2025).

- OECD. Guidance Document on Developing and Assessing Adverse Outcome Pathways. Available online: https://one.oecd.org/document/env/jm/mono(2013)6/en/pdf (accessed on 20 September 2025).

- de Paula Nunes, E.; Abou Dehn Pestana, B.; Pereira, B.B. Human biomonitoring and environmental health: A critical review of global exposure patterns, methodological challenges and research gaps. J. Toxicol. Environ. Health Part B 2025, 1–19. [Google Scholar]

- Birolli, W.G.; Lanças, F.M.; dos Santos Neto, Á.J.; Silveira, H.C.S. Determination of pesticide residues in urine by chromatography-mass spectrometry: Methods and applications. Front. Public Health 2024, 12, 1336014. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, U.J.; Hong, M.; Choi, Y.H. Environmental Pyrethroid Exposure and Cognitive Dysfunction in U.S. Older Adults: The NHANES 2001–2002. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 12005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hsieh, N.H.; Kwok, E.S.C. Biomonitoring-Based Risk Assessment of Pyrethroid Exposure in the U.S. Population: Application of High-Throughput and Physiologically Based Kinetic Models. Toxics 2025, 13, 216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Đuc, N.; Khanh, T.; Thang, P.; Hung, T.; Thu, P.; Chi, L.; Khuyen, V.; Tuan, N. Ultra-High Performance Liquid Chromatography–Tandem Mass Spectrometry Method Development and Validation to Quantify Simultaneously Six Urinary DIALKYL Phosphate Metabolites of Organophosphorus Pesticides. J. Mass. Spectrom. 2025, 60, e5128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seo, S.H.; Batterman, S.; Karvonen-Gutierrez, C.A.; Park, S.K. Determinants of urinary dialkyl phosphate metabolites in midlife women: The Study of Women’s Health Across the Nation Multi-Pollutant Study (SWAN-MPS). J. Expo. Sci. Environ. Epidemiol. 2025, 35, 590–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roca, M.; Miralles-Marco, A.; Ferré, J.; Pérez, R.; Yusà, V. Biomonitoring exposure assessment to contemporary pesticides in a school children population of Spain. Environ. Res. 2014, 131, 77–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iglesias-Gonzalez, A.; Hardy, E.M.; Appenzeller, B.M.R. Cumulative exposure to organic pollutants of French children assessed by hair analysis. Environ. Int. 2020, 134, 105332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sexton, K.; Needham, L.L.; Pirkle, J.L. Human Biomonitoring of Environmental Chemicals: Measuring chemicals in human tissues is the "gold standard" for assessing people’s exposure to pollution. Am. Sci. 2004, 92, 38–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angerer, J.; Ewers, U.; Wilhelm, M. Human biomonitoring: State of the art. Int. J. Hyg. Environ. Health 2007, 210, 201–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Connolly, A.; Coggins, M.A.; Koch, H.M. Human Biomonitoring of Glyphosate Exposures: State-of-the-Art and Future Research Challenges. Toxics 2020, 8, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tkalec, Ž.; Codling, G.; Tratnik, J.S.; Mazej, D.; Klánová, J.; Horvat, M.; Kosjek, T. Suspect and non-Targeted screening-Based Human Biomonitoring Identified 74 Biomarkers of Exposure in Urine of Slovenian Children. Environ. Pollut. 2022, 313, 120091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jaacks, L.M.; Diao, N.; Calafat, A.M.; Ospina, M.; Mazumdar, M.; Hasan, O.S.I.; Wright, R.; Quamruzzaman, Q.; Christiani, D.C. Association of Prenatal Pesticide Exposures with Adverse Pregnancy Outcomes and Stunting in Rural Bangladesh. Environ. Int. 2019, 133, 105243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.; Wang, X.; Feary McKenzie, J.; Mannetje, A.; Cheng, S.; He, C.; Leathem, J.; Pearce, N.; Sunyer, J.; Eskenazi, B.; et al. Pesticide Exposure in New Zealand School-Aged Children: Urinary Concentrations of Biomarkers and Assessment of Determinants. Environ. Int. 2022, 163, 107206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shentema, M.G.; Kumie, A.; Bråtveit, M.; Deressa, W.; Ngowi, A.V.; Moen, B.E. Pesticide Use and Serum Acetylcholinesterase Levels Among Flower Farm Workers in ethiopia-A Cross-Sectional Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menouni, A.; Duca, R.C.; Berni, I.; Khouchoua, M.; Ghosh, M.; El Ghazi, B.; Zouine, N.; Lhilali, I.; Akroute, D.; Pauwels, S.; et al. The Parental Pesticide and offspring’s Epigenome Study: Towards an Integrated Use of Human Biomonitoring of Exposure and Effect Biomarkers. Toxics 2021, 9, 332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makris, K.C.; Efthymiou, N.; Konstantinou, C.; Anastasi, E.; Schoeters, G.; Kolossa-Gehring, M.; Katsonouri, A. Oxidative Stress of Glyphosate, AMPA and Metabolites of Pyrethroids and Chlorpyrifos Pesticides Among Primary School Children in Cyprus. Environ. Res. 2022, 212, 113316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- HBM4EU. HBM4EU Priority Substances. Human Biomonitoirng for Europe. Available online: https://www.hbm4eu.eu/hbm4eu-substances/ (accessed on 6 August 2025).

- HBM4EU. The Project|HBM4EU-Science and Policy for a Healthy Future. Available online: https://www.hbm4eu.eu/the-project/ (accessed on 6 August 2025).

- Vorkamp, K.; López, M.E.; Gilles, L.; Göen, T.; Govarts, E.; Hajeb, P.; Katsonouri, A.; Knudsen, L.E.; Kolossa-Gehring, M.; Lindh, C.; et al. Coordination of chemical analyses under the European Human Biomonitoring Initiative (HBM4EU): Concepts, procedures and lessons learnt. Int. J. Hyg. Environ. Health 2023, 251, 114183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramhøj, L.; Svingen, T.; Vanhaecke, T. Editorial: European partnership on the assessment of risks from chemicals (PARC): Focus on new approach methodologies (NAMs) in risk assessment. Front. Toxicol. 2024, 6, 1461967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nagy, K.; Duca, R.C.; Lovas, S.; Creta, M.; Scheepers, P.T.; Godderis, L.; Ádám, B. Systematic review of comparative studies assessing the toxicity of pesticide active ingredients and their product formulations. Environ. Res. 2020, 181, 108926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villaverde, J.J.; Sevilla-Morán, B.; López-Goti, C.; Alonso-Prados, J.L.; Sandín-España, P. QSAR/QSPR models based on quantum chemistry for risk assessment of pesticides according to current European legislation. SAR QSAR Environ. Res. 2019, 31, 49–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goh, M.S.; Lam, S.D.; Yang, Y.F.; Naqiuddin, M.; Addis, S.N.K.; Yong, W.T.L.; Luang-In, V.; Sonne, C.; Ma, N.L. Omics technologies used in pesticide residue detection and mitigation in crop. J. Hazard. Mater. 2021, 420, 126624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bercu, J.; Masuda-Herrera, M.J.; Trejo-Martin, A.; Hasselgren, C.; Lord, J.; Graham, J.; Schmitz, M.; Milchak, L.; Owens, C.; Lal, S.H. A cross-industry collaboration to assess if acute oral toxicity (Q)SAR models are fit-for-purpose for GHS classification and labelling. Regul. Toxicol. Pharmacol. 2021, 120, 104843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McKim, J.M.; Bradbury, S.P.; Niemi, G.J. Fish acute toxicity syndromes and their use in the QSAR approach to hazard assessment. Environ. Health Perspect. 1987, 71, 171–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhhatarai, B.; Gramatica, P. Per-and polyfluoro toxicity (LC50 inhalation) study in rat and mouse using QSAR modeling. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 2010, 23, 528–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basant, N.; Gupta, S.; Singh, K.P. Predicting toxicities of diverse chemical pesticides in multiple avian species using tree-based QSAR approaches for regulatory purposes. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2015, 55, 1337–1348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, S.; Samal, A.; Ojha, P.K. Chemometrics-driven prediction and prioritization of diverse pesticides on chickens for addressing hazardous effects on public health. J. Hazard. Mater. 2024, 471, 134326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, S.; Ojha, P.K. Revolutionizing toxicity predictions of diverse chemicals to protect human health: Comparative QSAR and q-RASAR modeling. Toxicol. Lett. 2025, 411, 16–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Upton, R.N.; Foster, D.J.R.; Abuhelwa, A.Y. An introduction to physiologically-based pharmacokinetic models. Pediatr. Anesth. 2016, 26, 1036–1046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zartarian, V.; Xue, J.; Glen, G.; Smith, L.; Tulve, N.; Tornero-Velez, R. Quantifying children’s aggregate (dietary and residential) exposure and dose to permethrin: Application and evaluation of EPA’s probabilistic SHEDS-Multimedia model. J. Expo. Sci. Environ. Epidemiol. 2012, 22, 267–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tornero-Velez, R.; Davis, J.; Scollon, E.J.; Starr, J.M.; Setzer, R.W.; Goldsmith, M.R.; Chang, D.T.; Xue, J.; Zartarian, V.; De Vito, M.J.; et al. A pharmacokinetic model of cis-and trans-permethrin disposition in rats and humans with aggregate exposure application. Toxicol. Sci. 2012, 130, 33–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isaacs, K.K.; Glen, W.G.; Egeghy, P.; Goldsmith, M.R.; Smith, L.; Vallero, D.; Brooks, R.; Grulke, C.M.; Grulke, H.O. SHEDS-HT: An integrated probabilistic exposure model for prioritizing exposures to chemicals with near-field and dietary sources. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2014, 48, 12750–12759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Programme on Chemical Safety (IPCS). Characterization and Application of Physiologically Based Pharmacokinetic Models in Risk Assessment; World Health Organization, International Programme on Chemical Safety: Geneva, Switzerland, 2010; Available online: https://iris.who.int/server/api/core/bitstreams/9a07bd8a-bc8d-4c8c-9349-63e46fca607f/content (accessed on 15 September 2025).

- Meek, M.B.; Barton, H.A.; Bessems, J.G.; Lipscomb, J.C.; Krishnan, K. Case study illustrating the WHO IPCS guidance on characterization and application of physiologically based pharmacokinetic models in risk assessment. Regul. Toxicol. Pharmacol. 2013, 66, 116–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Approaches for the Application of Physiologically Based Pharmacokinetic (PBPK) Models and Supporting Data in Risk Assessment (Final Report); NCEA Publication: S. EPA; U.S. Environmental Protection Agency: Washington, DC, USA, 2006. Available online: https://iris.epa.gov/Document/&deid=157668 (accessed on 15 September 2025).

- OECD. Guidance document on the characterisation, validation and reporting of Physiologically Based Kinetic (PBK) models for regulatory purposes. In OECD Series on Testing and Assessment; No. 331; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLanahan, E.D.; El-Masri, H.A.; Sweeney, L.M.; Kopylev, L.Y.; Clewell, H.J.; Wambaugh, J.F.; Schlosser, P.M. Physiologically based pharmacokinetic model use in risk assessment—Why being published is not enough. Toxicol. Sci. 2012, 126, 5–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perovani, I.S.; Yamamoto, P.A.; da Silva, R.M.; Lopes, N.P.; de Moraes, N.V.; de Oliveira, A.R.M. Unveiling CYP450 inhibition by the pesticide prothioconazole through integrated in vitro studies and PBPK modeling. Arch. Toxicol. 2025, 99, 2845–2854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mangas, I.; Spilioti, E.; Terron, A.; Panzarea, M.; Nepal, M.; Viviani, B.; Binaglia, M.; Crofton, K.M. European Food Safety Authority database for in vivo developmental neurotoxicity studies of pesticides. Crit. Rev. Toxicol. 2025, 55, 587–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Munnia, A.; Bollati, V.; Russo, V.; Ferrari, L.; Ceppi, M.; Bruzzone, M.; Dugheri, S.; Arcangeli, G.; Merlo, F.; Peluso, M. Traffic-Related Air Pollution and Ground-Level Ozone Associated Global DNA Hypomethylation and Bulky DNA Adduct Formation. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 2041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cao, L.; Kang, Q.; Tian, Y. Pesticide residues: Bridging the gap between environmental exposure and chronic disease through omics. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2024, 287, 117335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manzoor, R. Toxicity in the Twenty-First Century (Tox-21): A Multidisciplinary Approach for Toxicity Prediction of Marine Organic Pollutants. In Recent Trends in Marine Toxicological Assessment; Chuan, O.M., Hamid, N., Ghazali, A., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Anastas, P.T.; Warner, J.C. Principles of green chemistry. In Green Chemistry: Theory and Practice; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1998; Volume 29, pp. 14821–14842. [Google Scholar]

- Fitzgerald, D.P.; Herrmann, J.W.; Sandborn, P.A.; Schmidt, L.C.; Gogoll, T.H. Design for environment (DfE): Strategies, practices, guidelines, methods, and tools. Environ. Conscious Mech. Des. 2007, 1, 1–24. [Google Scholar]

- Jamin, E.L.; Bonvallot, N.; Tremblay-Franco, M.; Cravedi, J.P.; Chevrier, C.; Cordier, S.; Debrauwer, L. Untargeted profiling of pesticide metabolites by LC–HRMS: An exposomics tool for human exposure evaluation. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2014, 406, 1149–1161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lefèvre-Arbogast, S.; Chaker, J.; Mercier, F.; Barouki, R.; Coumoul, X.; Miller, G.W.; David, A.; Samieri, C. Assessing the contribution of the chemical exposome to neurodegenerative disease. Nat. Neurosci. 2024, 27, 812–821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kunde, H.; Ioannou, E.I.; Chovatiya, J.; Jagani, R.; Charisiadis, P.; Arora, M.; Andra, S.S.; Makris, K.C. An exposomics analysis of 125 biomarkers of exposure to food contaminants and biomarkers of oxidative stress: A randomized cross-over chrononutrition trial of healthy adults. Environ. Int. 2025, 202, 109682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gozali, L.; Kristina, H.J.; Yosua, A.; Zagloel, T.Y.M.; Masrom, M.; Susanto, S.; Tanujaya, H.; Irawan, A.P.; Gunadi, A.; Kumar, V.; et al. The improvement of block chain technology simulation in supply chain management (case study: Pesticide company). Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 3784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santos, R.d.A.; Teles, E.O.; Freires, F.G.M. Applying the Circular Economy Framework to Blockchain Agricultural Production. Sustainability 2024, 16, 8004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. EU Multi-Annual Control Programmes. Available online: https://food.ec.europa.eu/plants/pesticides/maximum-residue-levels/enforcement/eu-multi-annual-control-programmes_en (accessed on 15 September 2025).

- Nikolopoulou, D.; Ntzani, E.; Kyriakopoulou, K.; Anagnostopoulos, C.; Machera, K. Priorities and Challenges in Methodology for Human Health Risk Assessment from Combined Exposure to Multiple Chemicals. Toxics 2023, 11, 401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- D’Amore, T.; Smaoui, S.; Varzakas, T. Chemical Food Safety in Europe Under the Spotlight: Principles, Regulatory Framework and Roadmap for Future Directions. Foods 2025, 14, 1628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cattaneo, I.; Kalian, A.D.; Di Nicola, M.R.; Dujardin, B.; Levorato, S.; Mohimont, L.; Nathanail, A.V.; Carnessechi, E.; Astuto, M.C.; Tarazona, J.V.; et al. Risk Assessment of Combined Exposure to Multiple Chemicals at the European Food Safety Authority: Principles, Guidance Documents, Applications and Future Challenges. Toxins 2023, 15, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reale, E.; Zare Jeddi, M.; Paini, A.; Connolly, A.; Duca, R.; Cubadda, F.; Benfenati, E.; Bessems, J.; Galea, K.S.; Dirven, H.; et al. Human Biomonitoring and Toxicokinetics as Key Building Blocks for next Generation Risk Assessment. Environ. Int. 2024, 184, 108474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Active Substance | Chemical Class (Type) | Health Effects | Environmental Effects | Status (Status Year) | Regulatory Field |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| List I | |||||

| Asulam | Carbamate (herbicide) | No | Yes | Legally adopted (2024) | PPPR |

| Benthiavalicarb | Carbamate (fungicide) | Yes | No | Legally adopted (2024) Concluded ED in EFSA opinion (2021) | PPPR |

| Clofentezine | Tetrazine (acaricide) | Yes | No | Legally adopted (2024) Concluded ED in EFSA opinion (2021) | PPPR |

| Cyanamide | Nitrile (herbicide) | Yes | Yes | Legally adopted (2024) Concluded ED in EFSA opinion (2021) | BPR |

| Dimethomorph | Morpholine (fungicide) | Yes | Yes | Legally adopted (2024) Concluded ED in EFSA opinion (2023) | PPPR |

| Mancozeb | Dithiocarbamate (fungicide) | Yes | Yes | Legally adopted (2021) Concluded ED in EFSA opinion (2020) | PPPR |

| Mepanipyrim | Aminopyrimidines (fungicide) | Yes | Yes | Legally adopted (2024) Concluded ED in EFSA opinion (2023) | PPPR |

| Metiram | Dithiocarbamate (fungicide) | Yes | No | Legally adopted (2024) Concluded ED in EFSA opinion (2023) | PPPR |

| Metribuzin | 1,2,4-triazines (herbicide) | Yes | No | Legally adopted (2024) Concluded ED in EFSA opinion (2023) | PPPR |

| Propiconazole | Triazole (fungicide) | Yes | Yes | Legally adopted (2024) Concluded ED in BPC opinion (2022) | PPPR |

| Triflusulfuron-methyl | sulfonylurea (herbicide) | Yes | No | Legally adopted (2024) Concluded ED in EFSA opinion (2022) | PPPR |

| List II | |||||

| Deltamethrin | Pyrethroid (type 2) ester (insecticide) | Yes | No | Commission EDC list (2019) | Cosmetics |

| Ziram | Dimethyldithiocarbamate (fungicide) | Yes | Yes | CoRAP (ECHA) list (2012) | REACH |

| Diuron | Urea (herbicide) | Yes | Yes | Concluded ED in SEV (2024) CoRAP (ECHA) list (2012) | REACH |

| Thiabendazole | Benzimidazoles (fungicide) | Yes | No | Concluded ED in EFSA opinion (2022) | PPPR |

| Fludioxonil | Phenylpyrrole (fungicide) | Yes | Yes | Concluded ED in EFSA opinion (2024) | PPPR |

| Flufenacet | Thiadiazole (herbicide) | Yes | Yes | Concluded ED in EFSA opinion (2024) | PPPR |

| Cyprodinil | Anilinopyrimidine (fungicide) | Yes | Yes | Concluded ED in EFSA opinion (2025) | PPPR |

| 3-iodo-2-propynylbutylcarbamate (IPBC) | Carbamate (fungicide) | No | Yes | Concluded ED in BPC opinion (2024) | BPR |

| List III | |||||

| Prochloraz | Imidazole (fungicide) | Yes | No | List III National Authority evaluation (2020) | - |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Buonsenso, F. Scientific and Regulatory Perspectives on Chemical Risk Assessment of Pesticides in the European Union. J. Xenobiot. 2025, 15, 173. https://doi.org/10.3390/jox15050173

Buonsenso F. Scientific and Regulatory Perspectives on Chemical Risk Assessment of Pesticides in the European Union. Journal of Xenobiotics. 2025; 15(5):173. https://doi.org/10.3390/jox15050173

Chicago/Turabian StyleBuonsenso, Fabio. 2025. "Scientific and Regulatory Perspectives on Chemical Risk Assessment of Pesticides in the European Union" Journal of Xenobiotics 15, no. 5: 173. https://doi.org/10.3390/jox15050173

APA StyleBuonsenso, F. (2025). Scientific and Regulatory Perspectives on Chemical Risk Assessment of Pesticides in the European Union. Journal of Xenobiotics, 15(5), 173. https://doi.org/10.3390/jox15050173