Emotional Intelligence in the Professional Development of Nurses: From Training to the Improvement of Healthcare Quality

Abstract

1. Introduction

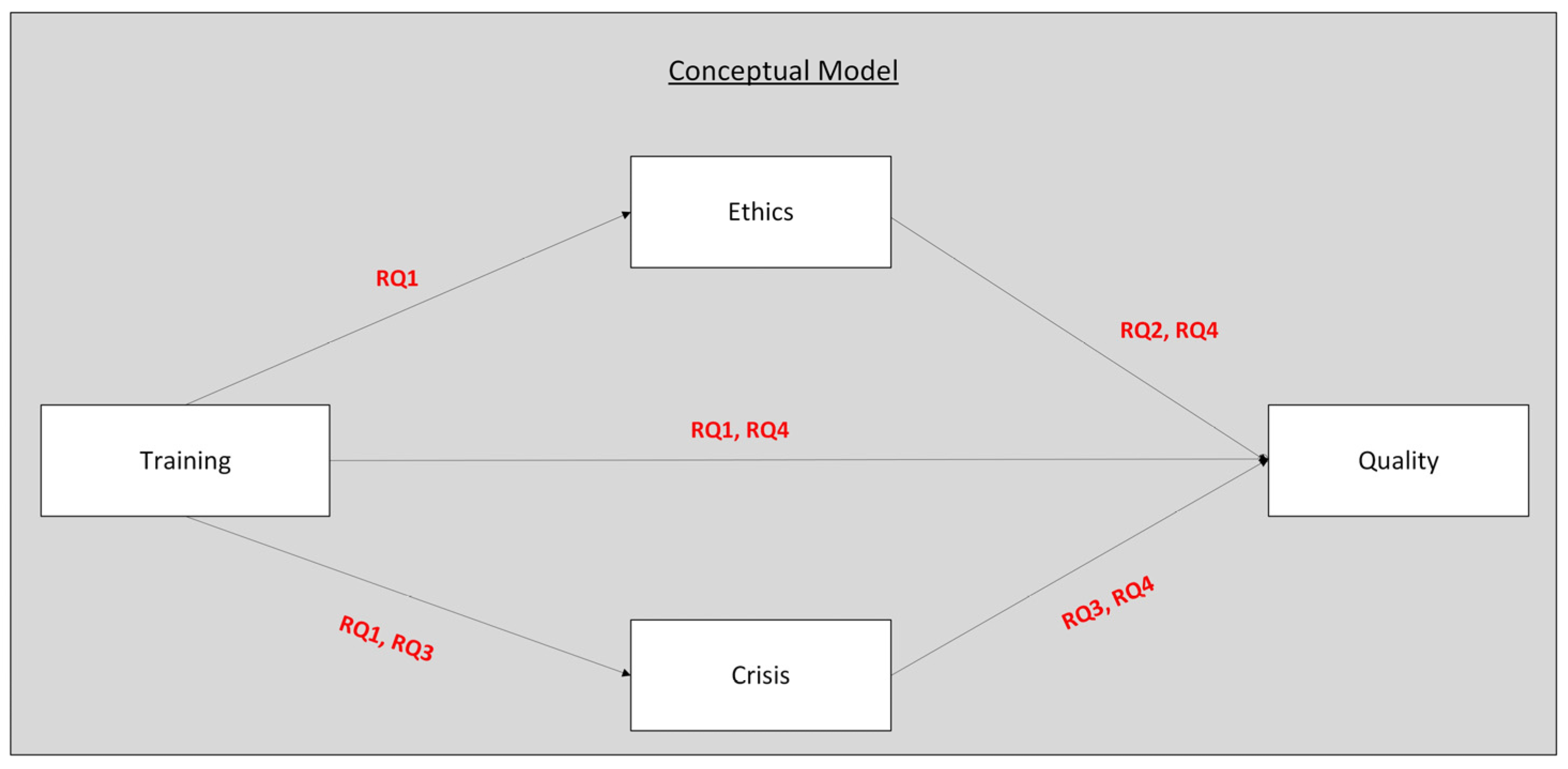

Conceptual Model

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Setting

2.2. Data Collection Procedure

2.3. Sampling

2.4. Measurements

2.5. Questionnaire Development and Content Validation

2.6. Statistical Analysis

- Training → Ethics → Quality of Care

- Training → Crisis Management → Quality of Care

2.7. Model Fit and Bias Assessment

2.8. Ethical Considerations

3. Results

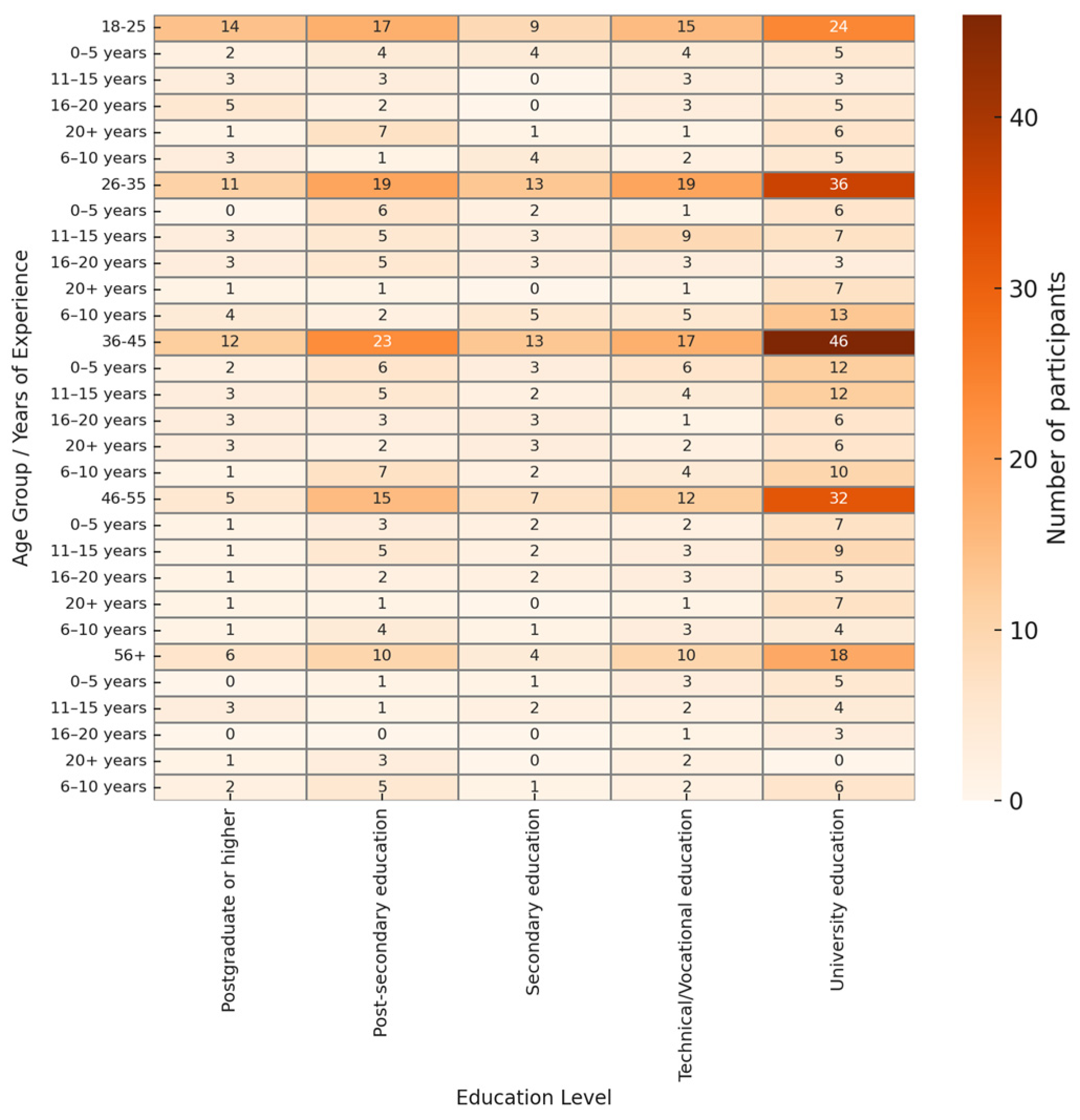

3.1. Descriptive Statistics

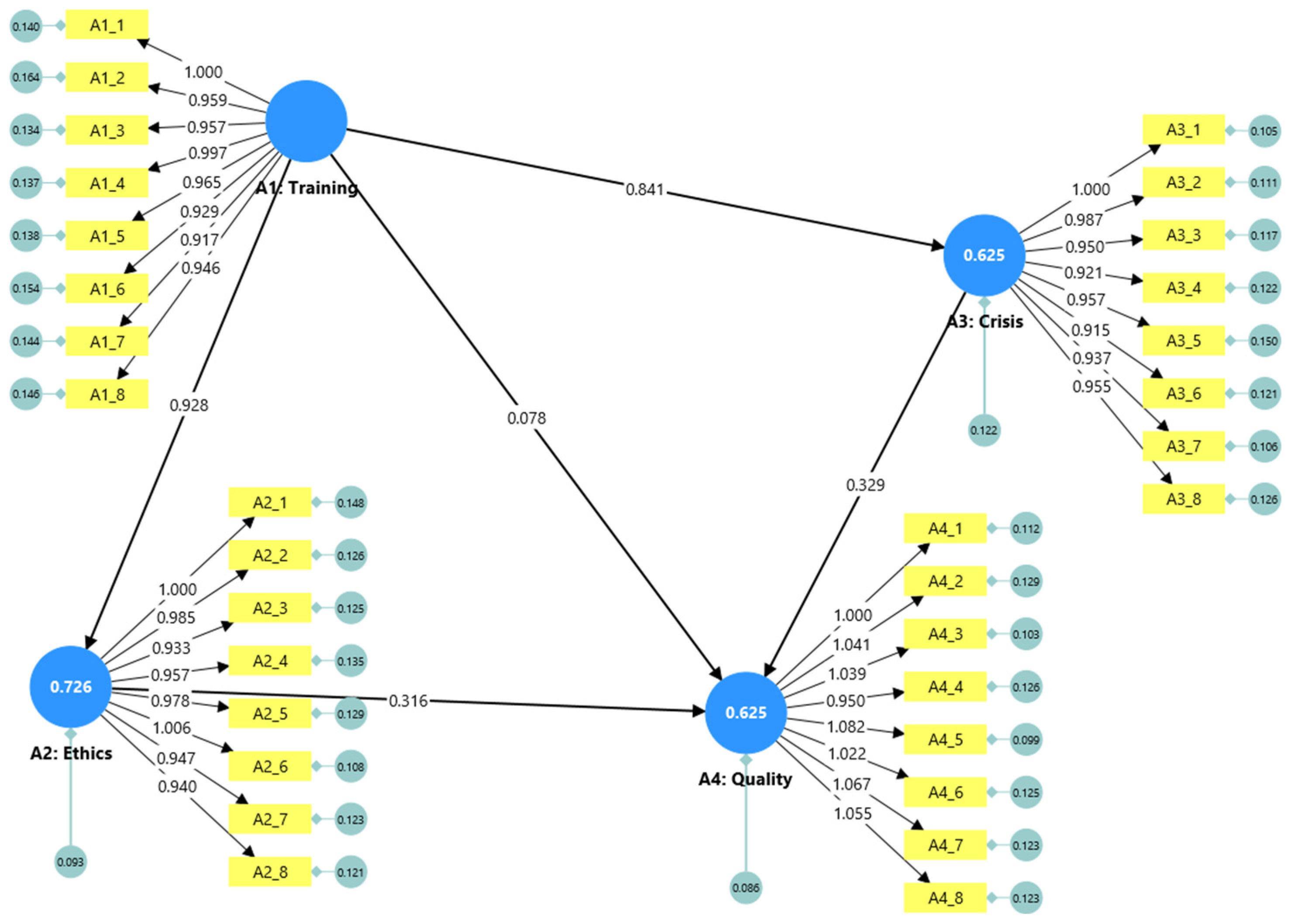

3.2. Measurement Model and Model Fit

3.3. Structural Model Results

3.4. Mediation Analysis

3.5. Research Questions

3.5.1. RQ1: Improvement of Emotional Intelligence Skills

3.5.2. RQ2: EI and Ethical Standards

3.5.3. RQ3: EI and Crisis Management

3.5.4. RQ4: EI, Quality of Care, and Patient Satisfaction

4. Discussion

4.1. Practical Implications

4.2. Theoretical Implications

4.3. Limitations and Future Research

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Public Involvement Statement

Guidelines and Standards Statement

Use of Artificial Intelligence

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Estimated Model | Null Model | |

|---|---|---|

| Chi-square | 497.672 | 12,084.297 |

| Number of model parameters | 69.000 | 32.000 |

| Number of observations | 407.000 | n/a |

| Degrees of freedom | 459.000 | 496.000 |

| p value | 0.103 | 0.000 |

| ChiSqr/df | 1.084 | 24.364 |

| RMSEA | 0.014 | 0.240 |

| RMSEA LOW 90% CI | 0.000 | 0.236 |

| RMSEA HIGH 90% CI | 0.023 | 0.243 |

| GFI | 0.929 | n/a |

| AGFI | 0.919 | n/a |

| PGFI | 0.808 | n/a |

| SRMR | 0.033 | n/a |

| NFI | 0.959 | n/a |

| TLI | 0.996 | n/a |

| CFI | 0.997 | n/a |

| AIC | 635.672 | n/a |

| BIC | 912.280 | n/a |

| Parameter Estimates | Standard Errors | T Values | p Values | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| A1_1 <- A1: Training | 1.000 | n/a | n/a | n/a |

| A1_2 <- A1: Training | 0.959 | 0.052 | 18.482 | 0.000 |

| A1_3 <- A1: Training | 0.957 | 0.049 | 19.460 | 0.000 |

| A1_4 <- A1: Training | 0.997 | 0.050 | 19.893 | 0.000 |

| A1_5 <- A1: Training | 0.965 | 0.050 | 19.429 | 0.000 |

| A1_6 <- A1: Training | 0.929 | 0.050 | 18.556 | 0.000 |

| A1_7 <- A1: Training | 0.917 | 0.049 | 18.718 | 0.000 |

| A1_8 <- A1: Training | 0.946 | 0.050 | 19.010 | 0.000 |

| A2_1 <- A2: Ethics | 1.000 | n/a | n/a | n/a |

| A2_2 <- A2: Ethics | 0.985 | 0.045 | 21.737 | 0.000 |

| A2_3 <- A2: Ethics | 0.933 | 0.044 | 21.176 | 0.000 |

| A2_4 <- A2: Ethics | 0.957 | 0.045 | 21.054 | 0.000 |

| A2_5 <- A2: Ethics | 0.978 | 0.045 | 21.545 | 0.000 |

| A2_6 <- A2: Ethics | 1.006 | 0.044 | 22.655 | 0.000 |

| A2_7 <- A2: Ethics | 0.947 | 0.044 | 21.455 | 0.000 |

| A2_8 <- A2: Ethics | 0.940 | 0.044 | 21.369 | 0.000 |

| A3_1 <- A3: Crisis | 1.000 | n/a | n/a | n/a |

| A3_2 <- A3: Crisis | 0.987 | 0.041 | 23.856 | 0.000 |

| A3_3 <- A3: Crisis | 0.950 | 0.041 | 22.934 | 0.000 |

| A3_4 <- A3: Crisis | 0.921 | 0.041 | 22.322 | 0.000 |

| A3_5 <- A3: Crisis | 0.957 | 0.044 | 21.597 | 0.000 |

| A3_6 <- A3: Crisis | 0.915 | 0.041 | 22.304 | 0.000 |

| A3_7 <- A3: Crisis | 0.937 | 0.040 | 23.441 | 0.000 |

| A3_8 <- A3: Crisis | 0.955 | 0.042 | 22.573 | 0.000 |

| A4_1 <- A4: Quality | 1.000 | n/a | n/a | n/a |

| A4_2 <- A4: Quality | 1.041 | 0.053 | 19.601 | 0.000 |

| A4_3 <- A4: Quality | 1.039 | 0.050 | 20.643 | 0.000 |

| A4_4 <- A4: Quality | 0.950 | 0.051 | 18.721 | 0.000 |

| A4_5 <- A4: Quality | 1.082 | 0.051 | 21.209 | 0.000 |

| A4_6 <- A4: Quality | 1.022 | 0.052 | 19.560 | 0.000 |

| A4_7 <- A4: Quality | 1.067 | 0.053 | 20.056 | 0.000 |

| A4_8 <- A4: Quality | 1.055 | 0.053 | 19.966 | 0.000 |

| Harman’s Single-Factor Test | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Factor | SS Loadings | % of Variance | Cumulative % |

| 1 | 13.44 | 42.0 | 42.0 |

| Cronbach’s Alpha (Standardized) | Cronbach’s Alpha (Unstandardized) | Composite Reliability (Rho_c) | Average Variance Extracted (AVE) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| A1: Training | 0.937 | 0.936 | 0.936 | 0.645 |

| A2: Ethics | 0.953 | 0.952 | 0.953 | 0.715 |

| A3: Crisis | 0.952 | 0.951 | 0.952 | 0.711 |

| A4: Quality | 0.944 | 0.944 | 0.943 | 0.674 |

| A1: Training | A2: Ethics | A3: Crisis | A4: Quality | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| A1: Training | ||||

| A2: Ethics | 0.839 | |||

| A3: Crisis | 0.774 | 0.763 | ||

| A4: Quality | 0.709 | 0.748 | 0.742 |

| A1: Training | A2: Ethics | A3: Crisis | A4: Quality | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| A1: Training | 0.803 | |||

| A2: Ethics | 0.852 | 0.846 | ||

| A3: Crisis | 0.791 | 0.674 | 0.843 | |

| A4: Quality | 0.726 | 0.724 | 0.721 | 0.821 |

References

- Rossell, S.L.; Neill, E.; Phillipou, A.; Tan, E.J.; Toh, W.L.; Van Rheenen, T.E.; Meyer, D. An overview of current mental health in the general population of Australia during the COVID-19 pandemic: Results from the COLLATE project. Psychiatry Res. 2021, 296, 113660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goleman, D. Emotional Intelligence, 25th ed.; Bloomsbury: London, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Nadler, R.; Carswell, J.J.; Minda, J.P. Online Mindfulness Training Increases Well-Being, Trait Emotional Intelligence, and Workplace Competency Ratings: A Randomized Waitlist-Controlled Trial. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawashima, T.; Ota, Y.; Aikawa, G.; Watanabe, M.; Ashida, K.; Sakuramoto, H. Effectiveness of emotional intelligence training on nurses’ and nursing students’ emotional intelligence, resilience, stress, and communication skills: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Nurse Educ. Today 2025, 151, 106743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, L.; Huang, L.; Chen, Q. Promoting resilience and lower stress in nurses and improving inpatient experience through emotional intelligence training in China: A randomized controlled trial. Nurse Educ. Today. 2021, 107, 105130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lambert, S. Role of emotional intelligence in effective nurse leadership. Nurs. Stand. 2021, 36, 45–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dulewicz, V.; Higgs, M. Emotional intelligence—A review and evaluation study. J. Manag. Psychol. 2000, 15, 341–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schutte, N.; Malouff, J. Increasing emotional intelligence through training: Current status and future directions. Int. J. Emot. Educ. 2013, 5, 56–72. [Google Scholar]

- Hutchinson, M.; Hurley, J.; Kozlowski, D.; Whitehair, L. The use of emotional intelligence capabilities in clinical reasoning and decision—Making: A qualitative, exploratory study. J. Clin. Nurs. 2017, 27, e600–e610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foji, S.; Vejdani, M.; Salehiniya, H.; Khosrorad, R. The effect of emotional intelligence training on general health promotion among nurse. J. Educ. Health Promot. 2020, 9, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karimi, L.; Leggat, S.G.; Bartram, T.; Rada, J. The effects of emotional intelligence training on the job performance of Australian aged care workers. Health Care Manag. Rev. 2020, 45, 41–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheraghi, R.; Parizad, N.; Alinejad, V.; Piran, M.; Almasi, L. The effect of emotional intelligence on nurses’ job performance: The mediating role of moral intelligence and occupational stress. BMC Nurs. 2025, 24, 130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skeva, A.; Salmond, E. Pursuing the inclusion of social and emotional learning in the everyday school environment; attitudes and tendencies that arise from the current Greek and international experience. Pan Hell. Conf. Educ. Sci. 2016, 2015, 1299–1306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Mattingly, V.; Kraiger, K. Can emotional intelligence be trained? A meta-analytical investigation. Hum. Resour. Manag. Rev. 2019, 29, 140–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cherry, M.G.; Fletcher, I.; O’Sullivan, H.; Dornan, T. Emotional intelligence in medical education: A critical review. Med. Educ. 2014, 48, 468–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeffrey, D.; Downie, R. Empathy—Can it be Taught? J. R. Coll. Physicians Edinb. 2016, 46, 107–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, H.; Miao, L. (Eds.) Transition and Opportunity: Strategies from Business Leaders on Making the Most of China’s Future; China and Globalization; Springer Nature: Singapore, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raeissi, P.; Zandian, H.; Mirzarahimy, T.; Delavari, S.; Zahirian Moghadam, T.; Rahimi, G. Relationship between communication skills and emotional intelligence among nurses. Nurs. Manag. 2019, 26, 31–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shah, M.K.; Gandrakota, N.; Cimiotti, J.P.; Ghose, N.; Moore, M.; Ali, M.K. Prevalence of and Factors Associated with Nurse Burnout in the US. JAMA Netw. Open. 2021, 4, e2036469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Junges, J.R.; Zóboli, E.L.C.P.; Schaefer, R.; Nora, C.R.D.; Basso, M. Validation of the comprehensiveness of an instrument on ethical problems in primary care. Rev. Gaúcha Enferm. 2014, 35, 148–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, H.J.; Hur, W.-M.; Moon, T.-W.; Jun, J.-K. Is all support equal? The moderating effects of supervisor, coworker, and organizational support on the link between emotional labor and job performance. BRQ Bus. Res. Q. 2017, 20, 124–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luke, D.M.; Gawronski, B. Political Ideology and Moral Dilemma Judgments: An Analysis Using the CNI Model. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 2021, 47, 1520–1531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karimi, L.; Leggat, S.G.; Bartram, T.; Afshari, L.; Sarkeshik, S.; Verulava, T. Emotional intelligence: Predictor of employees’ wellbeing, quality of patient care, and psychological empowerment. BMC Psychol. 2021, 9, 93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wocial, L. In Search of a Moral Community. OJIN Online J. Issues Nurs. 2018, 23. Available online: https://ojin.nursingworld.org/table-of-contents/volume-23-2018/number-1-january-2018/search-of-moral-community/ (accessed on 14 April 2025). [CrossRef]

- Amiri, E.; Ebrahimi, H.; Vahidi, M.; Asghari Jafarabadi, M.; Namdar Areshtanab, H. Relationship between nurses’ moral sensitivity and the quality of care. Nurs. Ethics 2019, 26, 1265–1273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belay, A.S.; Kassie, A. Emotional Intelligence and Clinical Performance of Undergraduate Nursing Students During Obstetrics and Gynecology Nursing Practice; Mizan-Tepi University, South West Ethiopia. Adv. Med. Educ. Pract. 2021, 12, 913–922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Numminen, O.; Repo, H.; Leino-Kilpi, H. Moral courage in nursing: A concept analysis. Nurs. Ethics 2017, 24, 878–891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silén, M.; Svantesson, M.; Kjellström, S.; Sidenvall, B.; Christensson, L. Moral distress and ethical climate in a Swedish nursing context: Perceptions and instrument usability. J. Clin. Nurs. 2011, 20, 3483–3493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schoenfelder, J.; Heins, J.; Brunner, J.O. Task assignments with rotations and flexible shift starts to improve demand coverage and staff satisfaction in healthcare. J. Sched. 2025, 28, 329–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahnavazi, M.; Parsa-Yekta, Z.; Yekaninejad, M.-S.; Amaniyan, S.; Griffiths, P.; Vaismoradi, M. The effect of the emotional intelligence education programme on quality of life in haemodialysis patients. Appl. Nurs. Res. 2018, 39, 18–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seitz, C. The European Health Union and the protection of public health in the European Union: Is the European Union prepared for future cross-border health threats? ERA Forum 2023, 23, 543–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roukas, D.; Tsouvelas, G. Natural disasters and communication strategy and healthcare systems. Arch. Hell. Med. 2025, 42, 14–28. [Google Scholar]

- Soltani, T.; Baghianimoghadam, M.H.; Ehrampoush, M.H.; Baghian, N.; Jafari, A. Knowledge, Attitude, and Performance of Nurses’Crisis Management in Natural Disasters in Yazd City. J. Community Health Res. 2016, 5, 195–201. [Google Scholar]

- Tommasi, M.; Sergi, M.R.; Picconi, L.; Saggino, A. The location of emotional intelligence measured by EQ-i in the personality and cognitive space: Are there gender differences? Front. Psychol. 2023, 13, 985847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fitzpatrick, J.J.; Alfes, C.M. Nurse Leadership and Management: Foundations for Effective Administration, 1st ed.; Springer Publishing Company: New York, NY, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Usher, K.; Redman-MacLaren, M.L.; Mills, J.; West, C.; Casella, E.; Hapsari, E.D.; Bonita, S.; Rosaldo, R.; Liswar, A.K.; Zang Amy, Y. Strengthening and preparing: Enhancing nursing research for disaster management. Nurse Educ. Pract. 2015, 15, 68–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Labrague, L.J.; Yboa, B.C.; McEnroe–Petitte, D.M.; Lobrino, L.R.; Brennan, M.G.B. Disaster Preparedness in Philippine Nurses. J. Nurs. Sch. 2016, 48, 98–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morrison, L.E.; Joy, J.P. Secondary traumatic stress in the emergency department. J. Adv. Nurs. 2016, 72, 2894–2906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nightingale, S.; Spiby, H.; Sheen, K.; Slade, P. The impact of emotional intelligence in health care professionals on caring behaviour towards patients in clinical and long-term care settings: Findings from an integrative review. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2018, 80, 106–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Loke, A.Y.; Guo, C.; Molassiotis, A. Development of disaster nursing education and training programs in the past 20 years (2000–2019): A systematic review. Nurse Educ. Today 2021, 99, 104809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, K.L.; Iseler, J.I. The Relationship of Bedside Nurses’ Emotional Intelligence with Quality of Care. J. Nurs. Care Qual. 2014, 29, 174–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oyur Celik, G. The relationship between patient satisfaction and emotional intelligence skills of nurses working in surgical clinics. Patient Prefer. Adherence 2017, 11, 1363–1368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Codier, E.; Codier, D.D. Could Emotional Intelligence Make Patients Safer? AJN Am. J. Nurs. 2017, 117, 58–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Søvold, L.E.; Naslund, J.A.; Kousoulis, A.A.; Saxena, S.; Qoronfleh, M.W.; Grobler, C.; Münter, L. Prioritizing the Mental Health and Well-Being of Healthcare Workers: An Urgent Global Public Health Priority. Front. Public Health 2021, 9, 679397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Szczygieł, D.; Mikolajczak, M. Why are people high in emotional intelligence happier? They make the most of their positive emotions. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2017, 117, 177–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weng, H.-C.; Chen, H.-C.; Chen, H.-J.; Lu, K.; Hung, S.-Y. Doctors’ emotional intelligence and the patient–doctor relationship. Med. Educ. 2008, 42, 703–711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saikia, M.; George, L.S.; Unnikrishnan, B.; Nayak, B.S.; Ravishankar, N. Thirty years of emotional intelligence: A scoping review of emotional intelligence training programme among nurses. Int. J. Ment. Health Nurs. 2024, 33, 37–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Öztürk, Ş. The effect of a distance-delivered mindfulness-based psychoeducation program on the psychological well-being, emotional intelligence and stress levels of nursing students in Turkey: A randomized controlled study. Health Educ. Res. 2023, 38, 575–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Economou, C.; Kaitelidou, D.; Katsikas, D.; Siskou, O.; Zafiropoulou, M. Impacts of the economic crisis on access to healthcare services in Greece with a focus on the vulnerable groups of the population1. Soc. Cohes. Dev. 2016, 9, 99–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakoyannis, M. Investigating Organizational Culture in a Public Hospital: A Case Study; National School of Public Administration: Athens, Greece, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Polit, D.F.; Beck, C.T. Nursing Research: Generating and Assessing Evidence for Nursing Practice, 11th ed.; international edition; Wolters Kluwer: Philadelphia, PA, USA; Baltimore, MD, USA; New York, NY, USA; London, UK; Buenos Aires, Argentina; Hong Kong; Sydney, Australia; Tokyo, Japan, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Etikan, I. Comparison of Convenience Sampling and Purposive Sampling. Am. J. Theor. Appl. Stat. 2016, 5, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sedgwick, P. Convenience sampling. BMJ 2013, 347, f6304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herbert, R.; Edgar, L. Emotional Intelligence: A Primal Dimension of Nursing Leadership? Nurs. Leadersh. 2004, 17, 56–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stichler, J.F. Emotional Intelligence. Awhonn Lifelines 2006, 10, 422–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayre, C.; Scally, A.J. Critical Values for Lawshe’s Content Validity Ratio: Revisiting the Original Methods of Calculation. Meas. Eval. Couns. Dev. 2014, 47, 79–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polit, D.F.; Beck, C.T. The content validity index: Are you sure you know what’s being reported? critique and recommendations. Res. Nurs. Health 2006, 29, 489–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hair, J.F.; Black, W.C.; Babin, B.J.; Anderson, R.E. Multivariate Data Analysis, 8th ed.; Cengage: Andover, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Byrne, B.M. Structural Equation Modeling with AMOS: Basic Concepts, Applications, and Programming, 3rd ed.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2016; Available online: https://www.taylorfrancis.com/books/9781317633136 (accessed on 15 June 2025). [CrossRef]

- Preacher, K.J.; Hayes, A.F. Asymptotic and resampling strategies for assessing and comparing indirect effects in multiple mediator models. Behav. Res. Methods 2008, 40, 879–891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheung, M.W.L. Some reflections on combining meta—Analysis and structural equation modeling. Res. Synth. Methods 2019, 10, 15–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Henseler, J.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. A new criterion for assessing discriminant validity in variance-based structural equation modeling. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2015, 43, 115–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Evaluating Structural Equation Models with Unobservable Variables and Measurement Error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, L.; Bentler, P.M. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Struct. Equ. Model. Multidiscip. J. 1999, 6, 1–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; MacKenzie, S.B.; Lee, J.Y.; Podsakoff, N.P. Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. J. Appl. Psychol. 2003, 88, 879–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waskom, M. seaborn: Statistical data visualization. J. Open Source Softw. 2021, 6, 3021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunter, J.D. Matplotlib: A 2D Graphics Environment. Comput. Sci. Eng. 2007, 9, 90–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharjee, A. Effectiveness Of Emotional Intelligence Training Programs for Healthcare Providers in Kolkata. Educ. Adm. Theory Pract. 2024, 30, 3748–3757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doğan, P.; Tarhan, M.; Kürklü, A. Impact of interactive ethics education program on nurses’ moral sensitivity. Nurs. Ethics 2025, 09697330251324319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McQueen, A.C.H. Emotional intelligence in nursing work. J. Adv. Nurs. 2004, 47, 101–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heffernan, M.; Quinn Griffin, M.T.; McNulty, S.R.; Fitzpatrick, J.J. Self—Compassion and emotional intelligence in nurses. Int. J. Nurs. Pract. 2010, 16, 366–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Berrocal, P.; Extremera, N. Ability Emotional Intelligence, Depression, and Well-Being. Emot. Rev. 2016, 8, 311–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Silva, T.M.H.R. Fostering Emotional Intelligence for Competency Development in Nursing Education. In Advances in Educational Technologies and Instructional Design; IGI Global: Hershey, PA, USA, 2024; pp. 39–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akerjordet, K.; Severinsson, E. Emotional intelligence: A review of the literature with specific focus on empirical and epistemological perspectives. J. Clin. Nurs. 2007, 16, 1405–1416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rankin, B. Emotional intelligence: Enhancing values—Based practice and compassionate care in nursing. J. Adv. Nurs. 2013, 69, 2717–2725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lewis, H.S.; Cunningham, C.J.L. Linking Nurse Leadership and Work Characteristics to Nurse Burnout and Engagement. Nurs. Res. 2016, 65, 13–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Birks, Y.F.; Watt, I.S. Emotional intelligence and patient-centred care. J. R. Soc. Med. 2007, 100, 368–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCutcheon, K.; Lohan, M.; Traynor, M.; Martin, D. A systematic review evaluating the impact of online or blended learning vs. face-to-face learning of clinical skills in undergraduate nurse education. J. Adv. Nurs. 2014, 71, 255–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arthur Jr, W.; Bennett Jr, W.; Stanush, P.L.; McNelly, T.L. Factors That Influence Skill Decay and Retention: A Quantitative Review and Analysis. Hum. Perform. 1998, 11, 57–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blume, B.D.; Ford, J.K.; Baldwin, T.T.; Huang, J.L. Transfer of Training: A Meta-Analytic Review. J. Manag. 2010, 36, 1065–1105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mann, C.J. Observational research methods. Research design II: Cohort, cross sectional, and case-control studies. Emerg. Med. J. 2003, 20, 54–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaitelidou, D.; Kontogianni, A.; Galanis, P.; Siskou, O.; Mallidou, A.; Pavlakis, A.; Kostagiolas, P.; Theodorou, M.; Liaropoulos, L. Conflict management and job satisfaction in paediatric hospitals in Greece: Conflict and job satisfaction in Greek paediatric hospitals. J. Nurs. Manag. 2012, 20, 571–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karimi, L.; Leggat, S.G.; Donohue, L.; Farrell, G.; Couper, G.E. Emotional rescue: The role of emotional intelligence and emotional labour on well-being and job-stress among community nurses. J. Adv. Nurs. 2014, 70, 176–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tashakkori, A.; Teddlie, C. SAGE Handbook of Mixed Methods in Social & Behavioral Research; SAGE Publications, Inc.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2010; Available online: https://methods.sagepub.com/book/sage-handbook-of-mixed-methods-social-behavioral-research-2e (accessed on 14 June 2025). [CrossRef]

- Kline, R.B. Principles and Practice of Structural Equation Modeling, 4th ed.; Methodology in the social sciences; The Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Wolf, E.J.; Harrington, K.M.; Clark, S.L.; Miller, M.W. Sample Size Requirements for Structural Equation Models: An Evaluation of Power, Bias, and Solution Propriety. Educ. Psychol. Meas. 2013, 73, 913–934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Oostveen, C.J.; Mathijssen, E.; Vermeulen, H. Nurse staffing issues are just the tip of the iceberg: A qualitative study about nurses’ perceptions of nurse staffing. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2015, 52, 1300–1309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duffield, C.; Roche, M.; O’Brien-Pallas, L.; Catling-Paull, C.; King, M. Staff satisfaction and retention and the role of the Nursing Unit Manager. Collegian 2009, 16, 11–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yildirim, D.; Aycan, Z. Nurses’ work demands and work–family conflict: A questionnaire survey. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2008, 45, 1366–1378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Papastavrou, E.; Efstathiou, G.; Tsangari, H.; Karlou, C.; Patiraki, E.; Jarosova, D.; Balogh, Z.; Merkouris, A.; Suhonen, R. Patients’ decisional control over care: A cross-national comparison from both the patients’ and nurses’ points of view. Scand. J. Caring Sci. 2016, 30, 26–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Papastavrou, E.; Andreou, P.; Tsangari, H.; Merkouris, A. Linking patient satisfaction with nursing care: The case of care rationing—A correlational study. BMC Nurs. 2014, 13, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aiken, L.H.; Sloane, D.M.; Bruyneel, L.; Van Den Heede, K.; Griffiths, P.; Busse, R.; Diomidous, M.; Kinnunen, J.; Kózka, M.; Lesaffre, E.; et al. Nurse staffing and education and hospital mortality in nine European countries: A retrospective observational study. Lancet 2014, 383, 1824–1830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Item Code | Main Description of Each Question |

|---|---|

| Education and Development of Emotional Intelligence (EI) | |

| 1A | EI training improves stress management |

| 1B | Training helps with emotion regulation |

| 1C | EI training supports work relationships |

| 1D | Training should include EI education |

| 1E | Program can enhance patient empathy |

| 1F | EI skills need ongoing learning |

| 1G | EI reduces professional burnout |

| 1H | Willingness to join EI training |

| Ethics, Code of Conduct, and Emotional Intelligence | |

| 2A | EI helps keep ethical principles |

| 2B | EI assists ethical decision-making |

| 2C | High EI prevents rights violations |

| 2D | Empathy supports nursing ethics |

| 2E | EI supports professional behavior |

| 2F | EI helps ethical compliance |

| 2G | EI nurses protect patient rights |

| 2H | Low EI leads to ethical dilemmas |

| Emotional Intelligence in Crisis Management | |

| 3A | EI keeps calm in emergencies |

| 3B | Anxiety control aids decisions |

| 3C | Self-awareness helps ask for help |

| 3D | Recognizing feelings in patients during crisis |

| 3E | EI improves teamwork in emergencies |

| 3F | High EI reduces errors under pressure |

| 3G | EI defuses stressful situations |

| 3H | EI is vital for crisis management |

| Emotional Intelligence, Quality of Care, and Patient Satisfaction | |

| 4A | Empathy impacts care quality |

| 4B | Patients respond to understanding nurses |

| 4C | Self-regulation for politeness/professionalism |

| 4D | EI builds patient trust |

| 4E | Satisfaction when nurses listen and understand |

| 4F | Understanding emotions enables personalized care |

| 4G | Nurses’ EI affects patient satisfaction |

| 4H | EI supports patience and professionalism |

| Pathway | Effect Type | O | M | STDEV | t | p | 2.5% | 97.5% |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A1: Training → A2: Ethics | Direct | 0.928 | 0.928 | 0.056 | 16.675 | 0.000 | 0.830 | 1.045 |

| A1: Training → A3: Crisis | Direct | 0.841 | 0.841 | 0.049 | 17.201 | 0.000 | 0.747 | 0.935 |

| A2: Ethics → A4: Quality | Direct | 0.316 | 0.313 | 0.077 | 4.119 | 0.000 | 0.149 | 0.472 |

| A3: Crisis → A4: Quality | Direct | 0.329 | 0.332 | 0.057 | 5.768 | 0.000 | 0.215 | 0.446 |

| A1: Training → A4: Quality | Direct | 0.078 | 0.078 | 0.087 | 0.895 | 0.371 | −0.097 | 0.253 |

| A1: Training → A3: Crisis → A4: Quality | Specific Indirect | 0.277 | 0.279 | 0.050 | 5.553 | 0.000 | 0.180 | 0.385 |

| A1: Training → A2: Ethics → A4: Quality | Specific Indirect | 0.293 | 0.291 | 0.073 | 4.009 | 0.000 | 0.141 | 0.434 |

| A1: Training → A4: Quality (Total Indirect) | Total Indirect | 0.570 | 0.570 | 0.083 | 6.882 | 0.000 | 0.403 | 0.730 |

| A1: Training → A4: Quality | Total Effect | 0.648 | 0.647 | 0.043 | 15.153 | 0.000 | 0.566 | 0.733 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Chatzidimitriou, E.; Triantari, S.; Zervas, I. Emotional Intelligence in the Professional Development of Nurses: From Training to the Improvement of Healthcare Quality. Nurs. Rep. 2025, 15, 275. https://doi.org/10.3390/nursrep15080275

Chatzidimitriou E, Triantari S, Zervas I. Emotional Intelligence in the Professional Development of Nurses: From Training to the Improvement of Healthcare Quality. Nursing Reports. 2025; 15(8):275. https://doi.org/10.3390/nursrep15080275

Chicago/Turabian StyleChatzidimitriou, Efthymia, Sotiria Triantari, and Ioannis Zervas. 2025. "Emotional Intelligence in the Professional Development of Nurses: From Training to the Improvement of Healthcare Quality" Nursing Reports 15, no. 8: 275. https://doi.org/10.3390/nursrep15080275

APA StyleChatzidimitriou, E., Triantari, S., & Zervas, I. (2025). Emotional Intelligence in the Professional Development of Nurses: From Training to the Improvement of Healthcare Quality. Nursing Reports, 15(8), 275. https://doi.org/10.3390/nursrep15080275