Implementation Strategy for a Mandatory Interprofessional Training Program Using an Instructional Design Model

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Background

3. Theoretical Foundations

4. Instructional Theories and Design

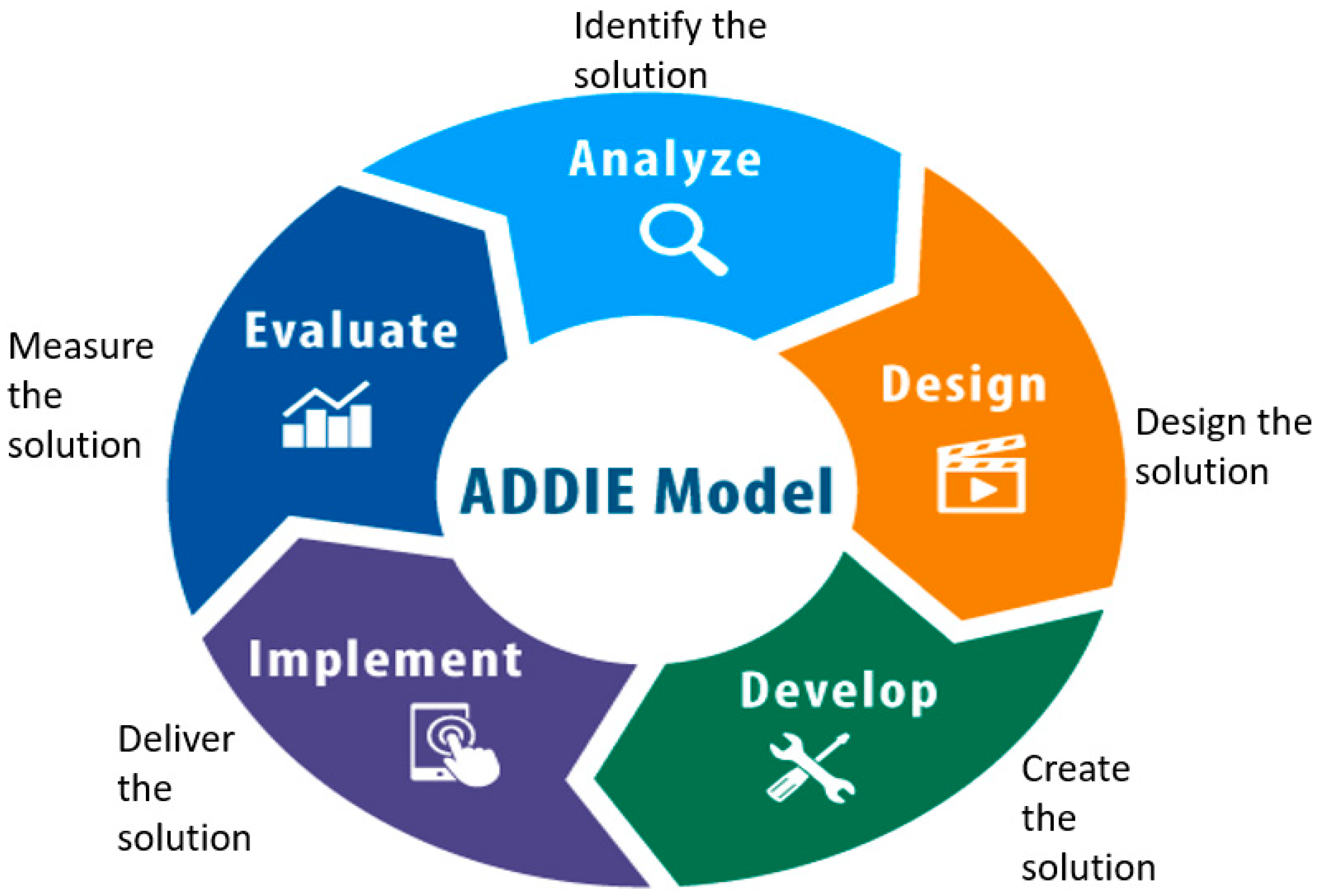

5. Method—Mandatory Training Process Using the ADDIE Model

5.1. Figure 1: Elements of the Instructional Design ‘ADDIE’ Model

5.2. Analysis—Best Approach to Design and Develop

- Assessing the organisations readiness by engaging key stakeholders in the process. Support and communication from Leadership is critical, ensuring alignment with the co design of the training [3].

- Consider organisational requirements around mandatory training and BLS.

- Analysing the health professional (HP) learner profiles (learner needs, cultural and special needs, working backgrounds and learning environment) and professional standards, and how mandatory practical training processes will be undertaken and the specific content to be taught.

- Analysing the broad goals of training and using task analysis (skills, knowledge, and communication) required by the HP. Discussing objectives and expectations of key stakeholders, underlying philosophies to be used and training resources and constraints.

- Analysing achievements, for example, quality of HP skill development and evaluating increased HP attendance rates.

- Determining training and competency needs for the BLS clinical assessors undertaking BLS assessments and requirements of other educational experts delivering mandatory training.

- Identifying the psychological safety of the team and HPs using BLS scenarios.

5.3. Design—Using the Analysis Information to Inform Design of the Learning and Assessment Resources

- Benchmarking involves comparing performances against known standards using appropriate assessment measures, that is, identifying learning outcomes and evaluating how the HP achieved successful completion of the assessment (learning objectives).

- Designing and selecting appropriate instructional strategies, for example, applying e-learning, assessment processes that are underpinned by the philosophies of idealism, realism, pragmatism and existentialism using blended learning theories of cognitivism and constructivism.

- Determining organisational requirements of the sequence of BLS skills to achieve.

- Engage the multidisciplinary stake holders in the co design to build clear communication to limit resistance.

5.4. Develop—Learning Materials Are Created

- Utilising instructional strategies to facilitate the learning objectives and validate the learning resources for the mandatory training sessions. Planning the logistics for the training (flexible scheduling can accommodate shift workers, venue, clinical assessors, tools, high fidelity mannequins). Shared resources can reduce duplication and promote collaboration.

- Embedding motivational learning aspects, for example, Keller’s ARCS Motivation Model incorporates Attention, Relevance, Confidence and Satisfaction components [26]. Research has shown that student motivation and interest in an IPE setting can be increased through the use of design strategies including video simulations, application of real-world scenarios, interactivity through gaming via online digital platforms that are cost effective and open-ended questions [26,38,39].

- Other design learning strategies that are associated with IPE include role play and inter-disciplinary or case-based group activities [38]. Create learning that builds compassion and communication. For the patient and self-care for the HPs.

- BLS training scenarios in an IPE setting. Rubrics for assessing interprofessional collaboration during training.Ensuring that training aligns with safety and quality standards.

5.5. Implementation—Delivering the Training to HP

- Start with a pilot group to allow for iterative refinement from initial data from HP feedback and facilitators to inform adjustments to the co design for continuous improvement and adaptation. Engage key stakeholders and HPs with the co design.

- Preparing the training setting to engage the HP for the training, for instance, provide feedback during practice, ensuring appropriate ergonomics of equipment and assessment processes.

- Providing professional development for the facilitator in IPE competencies by role modelling collaborative behaviours to manage team-based challenges, reflection, debrief and structured feedback. Delivering a combination of purposeful and interactive facilitation to the HPs [40].

5.6. Evaluation—Ensure Quality Training and Quality Learning Assessment Outcomes

- Confirming that training resources are accurate and up to date.

- Ensuring a safe work environment during BLS training and assessment.

- Reviewing and updating content to maintain quality.

- Empirical validation from pilot group looking at evaluation metrics of pre- and post-implementation surveys by HPs and clinical assessors of BLS competency and IPE collaboration, assessor skill level observation or use of an assessment tool. Qualitative feedback of the HPs experience by reviewing what was successful, what was learnt and what needs changing. Organisational data tracking of HPs skill competence aligning with accreditation standards to support future sustainability. Repeat ADDIE again, if required.

6. Evaluation

6.1. The Learning Setting

6.2. P Model Incorporating Presage–Process–Product

6.3. Task Analysis

6.4. Post Implementation Evaluation

7. Results

8. Discussion

9. Limitations and Recommendations

10. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Public Involvement Statement

Guidelines and Standards Statement

Use of Artificial Intelligence

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Spinelli, G.; Brogi, E.; Sidoti, A.; Pagnucci, A.; Forfori, F. Assessment of the knowledge level and experience of healthcare personnel concerning CPR and early defibrillation: An internal survey. BMC Cardiovasc. Disord. 2021, 21, 195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gum, L.; Salfi, J. Interprofessional education (IPE): Trends and context. In Clinical Education for Health Professions: Theory and Practice, 1st ed.; Nestel, D., Reedy, G., McKenna, L., Gough, S., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2023; pp. 168–180. [Google Scholar]

- Collaborative, I.E. IPEC Core Competencies for Interprofessional Collaborative Practice; Interprofessional Education Collaborative: Washington, DC, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- O’Leary, N.; Salmon, N.; Clifford, A. ‘It benefits patient care’: The value of practice-based IPE in healthcare curriculum. BMC Med. Educ. 2022, 20, 424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weeks, K.W.; Coben, D.; O’Neill, D.; Jones, A.; Weeks, A.; Brown, M.; Pontin, D. Developing and integrating nursing competence through authentic technology-enhanced clinical simulation education: Pedagogies for reconceptualising the theory-practice gap. Nurse Educ. Pract. 2019, 37, 29–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandran, K.V.; Abraham, S.V. Basic Life Support: Need of the Hour—A Study on the Knowledge of Basic Life Support among Young Doctors in India. Indian J. Crit. Care Med. 2020, 24, 332–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brix, L.D.; Skjødt-Jensen, A.M.; Jensen, T.H.; Aarkrog, V. Enhancing nursing students’ self-reported self-efficacy and professional competence in basic life support: The role of virtual simulation prior to high-fidelity training. Teach. Learn. Nurs. 2025, 20, e236–e243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Australian and New Zealand Committee on Resuscitation. ANZCOR Guidelines 8 Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation; Australian and New Zealand Committee on Resuscitation: Melbourne, Australia, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Cheung, J.H.; Kulasegaram, K.M. Beyond the tensions within transfer: Implications for adaptive expertise in the health professions. Adv. Health Sci. Educ. 2022, 27, 1293–1315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ornstein, A.C.; Hunkins, F.P. Curriculum: Foundations, Principles, and Issues; Pearson Education Limited: London, UK, 2018; Volume 7. [Google Scholar]

- Dalrymple, K.; di Napoli, R. Philosophy for healthcare professions education: A tool for thinking and practice. In Clinical Education for Health Professions: Theory and Practice; Nestel, D., Reedy, G., McKenna, L., Gough, S., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2023; pp. 555–572. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Q.; Li, Z.; Tang, S.; Zhou, C.; Castro, A.; Jiang, S.; Huang, C.; Xiao, J. Development of a blended emergent research training program for clinical nurses (part 1). BMS Nurs. 2022, 21, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knott, G.; Mylrea, M.; Glass, B. How should we prepare our pharmacist preceptors? Design, development and implementation of a training program in a regional Australian university. Pharmacy 2023, 11, 148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, B.; Zhang, J.; Qu, Z.; Jiang, N.; Chen, C.; Cheng, S. Development of COVID-19 infection prevention and control training program based on ADDIE model for clinical nurses: A pretest-posttest study. Nurs. Health Sci. 2024, 26, e13194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Chen, H.; Wang, X.; Huang, X.; Xie, D. Application of flipped classroom teaching method based on ADDIE concept in clinical teaching for neurology residents. BMC Med. Educ. 2024, 24, 366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tobase, L.; Peres, H.H.C.; Almeida, D.M.D.; Tomazini, E.A.S.; Ramos, M.B.; Polastri, T.F. Instructional design in the development of an online course on Basic Life Support. Rev. Esc. Enferm. USP 2017, 51, e03288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neubauer, F.B.; Wagner, F.L.; Lörwald, A.; Huwendiek, S. Sharpening the lens to evaluate interprofessional education and interprofessional collaboration by improving the conceptual framework: A critical discussion. BMC Med. Educ. 2024, 24, 615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care (ACSQHC). National Safety and Quality Health Service Standards. 2021. Available online: https://www.safetyandquality.gov.au/ (accessed on 14 December 2024).

- McAuliffe, M.J.; Gledhill, S. Enablers and barriers for mandatory training including Basic Life Support in an interprofessional environment: An integrated literature review. Nurse Educ. Today 2022, 119, 105539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abolfotouh, M.A.; Alnasser, M.A.; Berhanu, A.N.; Al-Turaif, D.A.; Alfayez, A.I. Impact of basic life-support training on the attitudes of health-care workers toward cardiopulmonary resuscitation and defibrillation. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2017, 17, 674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levett-Jones, T.; Burdett, T.; Chow, Y.L.; Jönsson, L.; Lasater, K.; Mathews, L. Case studies of interprofessional education initiatives from five countries. J. Nurs. Scholarsh. 2018, 50, 324–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babaei, S.; Taleghani, F.; Farzi, S. Components of compassionate care in nurses working in the cardiac wards: A descriptive qualitative study. J. Caring Sci. 2022, 11, 239–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinclair, S.; Hack, T.F.; McClement, S.; Raffin-Bouchal, S.; Chochinov, H.M.; Hagen, N.A. Healthcare providers perspectives on compassion training: A grounded theory study. BMC Med. Educ. 2020, 20, 249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thommes, M.S.; Schmidt, M.; Lambert, S.I.; Schauwinhold, M.T.; Klasen, M.; Sopka, S. Reflective practice improves Basic Life Support training outcomes: A randomized controlled study. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0287908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavlis, D.; Gkiosis, J. John Dewey, from philosophy of pragmatism to progressive education. J. Arts Humanit. 2017, 6, 23–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Başer, A.; Şahin, H. An interprofessional education program based on the ARCS-V motivation model on the theme of “Chronic Disease Management and Patient Safety”: Action research. BMC Med. Educ. 2025, 25, 532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, R.; Li, J.; Zhang, X.; Tian, D.; Zhang, Y. Effects of applying blended learning based on the ADDIE model in nursing staff training on improving theoretical and practical operational aspects. Front. Med. 2024, 11, 1413032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braungart, M.M.; Braungart, R.G.; Gramet, P.R. Applying learning theories to healthcare practice. In Nurse as Educator: Principles of Teaching and Learning, 6th ed.; Bastable, S., Ed.; Jones & Bartlett Learning: Burlington, MA, USA, 2021; pp. 79–120. [Google Scholar]

- Cecilio-Fernandes, D.; Patel, R.; Sandars, J. Using insights from cognitive science for the teaching of clinical skills: AMEE Guide No. 155. Med. Teach. 2023, 35, 1214–1223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.H.; Lin, C.C.; Han, C.Y.; Huang, Y.L.; Hsiao, P.R.; Chen, L.C. Undergraduate nursing student academic resilience during medical surgical clinical practicum: A constructivist analysis of Taiwanese experience. J. Prof. Nurs. 2021, 37, 521–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burgess, A.; Matar, E.; Roberts, C.; Haq, I.; Wynter, L.; Singer, J.; Kalman, E.; Bleasel, J. Scaffolding medical student knowledge and skills: Team-based learning (TBL) and case-based learning (CBL). BMC Med. Educ. 2021, 21, 238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coombs, N. Back to basics for nursing education in the 21st century. Nurse Educ. Today 2018, 68, 198–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, H.; Perry, S.; Badu, E.; Mwangi, F.; Mazurskyy, A.; Walters, J.; Tavener, M.; Noble, D.; Sherphard, C.; Lethbridge, L.; et al. A scoping review of interprofessional education in healthcare: Evaluating competency development, educational outcomes and challenges. BMC Med. Educ. 2025, 25, 409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.-O. Effect of case-based small-group learning on care workers’ emergency coping abilities. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 11458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aydin, A.; Gursoy, A.; Karal, H. Mobile care app development process; Using the ADDIE model to manage symptoms after breast cancer (step 1). Discov. Oncol. 2023, 14, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mackh, B.M. Pivoting Your Instruction: A Guide to Comprehensive Instructional Design for Faculty; Routledge: Oxfordshire, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Addie Model. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/training-development/php/about/ (accessed on 9 July 2025).

- Nagel, D.A.; Penner, J.L.; Halas, G.; Philip, M.T.; Cooke, C. Exploring experiential learning within interprofessional practice education initiatives for pre-licensure healthcare students: A scoping review. BMC Med. Educ. 2024, 24, 139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oudbier, J.; Verheijck, E.; van Diermen, D.; Tams, J.; Bramer, J.; Spaai, G. Enhancing the efectiveness of interprofessional education in health science education: A state-of-the-art review. BMC Med. Educ. 2024, 24, 1492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bogossian, F.; New, K.; George, K.; Barr, N.; Dodd, N.; Hamilton, A.L.; Nash, G.; Masters, N.; Pelly, F.; Reid, C.; et al. The implementation of interprofessional education: A scoping review. Adv. Health Sci. Educ. 2023, 28, 243–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Branch, R.M. Instructional Design: The ADDIE Approach, 1st ed.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Branch, R.M. Instructional design for training programs. In Educational Technology to Improve Quality and Access on a Global Scale Papers from the Educational Technology World Conference (ETWC 2016); Persichitte, K.A., Suparman, A., Spector, M., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2018; pp. 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Graham, A.C.; McAleer, S. An overview of realist evaluation for simulation-based education. Adv. Simul. 2018, 3, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parra, J.D.; Edwards, D.B., Jr. Systems, complexity and realist evaluation: Reflections from a large-scale education policy evaluation in Colombia. In Systems Thinking in International Education and Development; Faul, M., Savage., L., Eds.; Edward Elgar Publishing: Camberley, UK, 2023; pp. 183–203. [Google Scholar]

- Chan, Y.K. Investigating the relationship among extracurricular activities, learning approach and academic outcomes: A case study. Act. Learn. High. Educ. 2016, 17, 223–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grimes, T.C.; Guinan, E.M. Interprofessional education focused on medication safety: A systematic review. J. Interprofessional Care 2023, 37, 131–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbasi, M.; Asadoola, Y.; Ebrahimi, H.; Bahonar, E.; Dabirian, Z.; Esmaeili, S.M.; Mahdizadeh, A.; Mahdi, S. Comparison of mannequin-based simulation training method with virtual training method on nursing students’ learning cardiopulmonary resuscitation: A controlled randomized parallel trial. Iran. J. Nurs. Midwifery Res. 2024, 29, 425–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dabney, B.; Eid, F. Comparing educational frameworks: Unpacking differences between Fink’s and Bloom’s taxonomies in nursing education. Teach. Learn. Nurs. 2024, 19, 347–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Diggele, C.; Roberts, C.; Burgess, A.; Mellis, C. Interprofessional education: Tips for design and implementation. BMC Med. Educ. 2020, 20, 455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cortes, T. Building interprofessional teams through partnerships to address quality. Nurs. Sci. Q. 2019, 32, 288–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dempsey, A.; Robinson, C.; Moffatt, N.; Hennessy, T.; Bradshaw, A.; Teeling, S.P.; Ward, M.; McNamara, M. Lean Six Sigma redesign of a process for healthcare mandatory education in basic life support—A pilot study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 11653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Awaisi, A.; Ali, S.S.; Nada, A.A.; Rainkie, D.; Awaisu, A. Insights from healthcare academics on facilitating interprofessional education activities. J. Interprofessional Care 2021, 5, 760–770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Göksu, I.; Özcan, K.V.; Çakir, R.; Göktas, Y. Content analysis of research trends in instructional design models: 1999–2014. J. Learn. Des. 2017, 10, 85–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lafleur, A.; Babin, M.J.; Michaud-Couture, C.; Lacasse, M.; Giguère, Y.; Cantat, A.; Allen, C.; Gingras, N. Implementing competency-based education in multiple programs: A workshop to structure and monitor programs’priorities using ADDIE. Competency-Based Educ. 2021, 6, e1257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Q.; Chen, Q.; Ma, C.; Zhang, Y.; Gou, M.; Yang, W. Moral sensitivity, moral courage, and ethical behaviour among clinical nurses. Nurs. Ethics 2025, 32, 665–677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hislop, J.; Lane, J.; Hegarty, D.; Thomas, J. ‘Being and becoming a practice educator’: An AHP online programme. Clin. Teach. 2022, 21, e13648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| ADDIE Phase Applicable to BLS Training | IPE Competencies | BLS Specific Strategies | ExpectedOutcomes | Suggested Training Tools | Promote Compassion |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Analysis Identify learner needs, roles and skill gaps across health profession. Broad goals for the training. | Roles/Responsibilities, Values/Ethics. Assess team dynamics of the clinical assessors from different professions, role clarity and communication barriers. Assess organisational readiness. | Identify learning needs across HPs and clinical in BLS—AED adults and children’s assessments. | Clear understanding of team’s ability and training needs. | Needs/task analysis of training. BLS assessment reviewed with IPE educational experts. Analyse organisational compliance data requirements. | Identify emotional and psychological safety of the team and HPs using BLS scenarios. |

| Design Create learning objectives and inclusive and collaborative content assessment. | Interprofessional communication, Teams/Teamwork. Collaborative scenarios and role-based learning. | Choose instructional design strategies (simulation mannequins with feedback). Design assessment methods. | Defined learning goals, inclusive and relevant training plans that algins with organisation. | Lesson plans, relevant scenarios and key learning objectives. | Objectives that promote empathy and person-centred care |

| Develop Resources, simulation, and assessments training material. | Interprofessional communication, Roles/Responsibilities. Create content and input from multiple professions. | CPR mannequins with skill guide feedback, AED trainers and skill stations. Script guides for clinical assessors. | Functioning training equipment and resources for clinical assessors. | Logistical access and scheduling for training. Instruction, guides, IPE assessments, scenarios, videos, video simulations, role play, gaming, BLS learning on digital platform. Training for HPs aligns with quality standards. | Create learning that promotes compassion and communication and support during emergencies. Self-care for HPs. |

| Implementation Deliver training through workshop, simulation and team practice. | Teams/Teamwork, Interprofessional communication. Facilitate interprofessional participation and clinical assessor training and rotating Team Leader role. | Real time BLS simulation, closed loop communication and feedback. Pilot group and iterative refinement. | Teamwork improved, engaged collaborative BLS training and compliance data. | Training schedule, simulation guides and equipment. Attendance tracking. | Encourage compassionate interaction by the clinical assessor and HP during simulation and feedback on empathy. Dedicated time for reflective Practice end of the session. |

| Evaluation Assess learning performance and feedback for improvement | Values/Ethics, Roles/Responsibilities. Use peer review, team debrief and self-assessment from HPs and clinical assessors. | Skill checklist, scenario debrief and pre/post feedback survey. | Data to inform co design and refinement. Quality and continuous improvement to enhance IPE. Repeat ADDIE if required. | Evaluation metrics: qualitative pre/post survey feedback (skill improvement for HPs and clinical assessors. Iterative refinement. reflective Practice. | Observe and discuss compassionate behaviour for the patient during emergencies. Use peer review and reflective practice from clinical assessors and HPs. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Gledhill, S.; McAuliffe, M.J. Implementation Strategy for a Mandatory Interprofessional Training Program Using an Instructional Design Model. Nurs. Rep. 2025, 15, 274. https://doi.org/10.3390/nursrep15080274

Gledhill S, McAuliffe MJ. Implementation Strategy for a Mandatory Interprofessional Training Program Using an Instructional Design Model. Nursing Reports. 2025; 15(8):274. https://doi.org/10.3390/nursrep15080274

Chicago/Turabian StyleGledhill, Susan, and Mary Jane McAuliffe. 2025. "Implementation Strategy for a Mandatory Interprofessional Training Program Using an Instructional Design Model" Nursing Reports 15, no. 8: 274. https://doi.org/10.3390/nursrep15080274

APA StyleGledhill, S., & McAuliffe, M. J. (2025). Implementation Strategy for a Mandatory Interprofessional Training Program Using an Instructional Design Model. Nursing Reports, 15(8), 274. https://doi.org/10.3390/nursrep15080274