Informed Consent in Perinatal Care: Challenges and Best Practices in Obstetric and Midwifery-Led Models

Abstract

1. Introduction

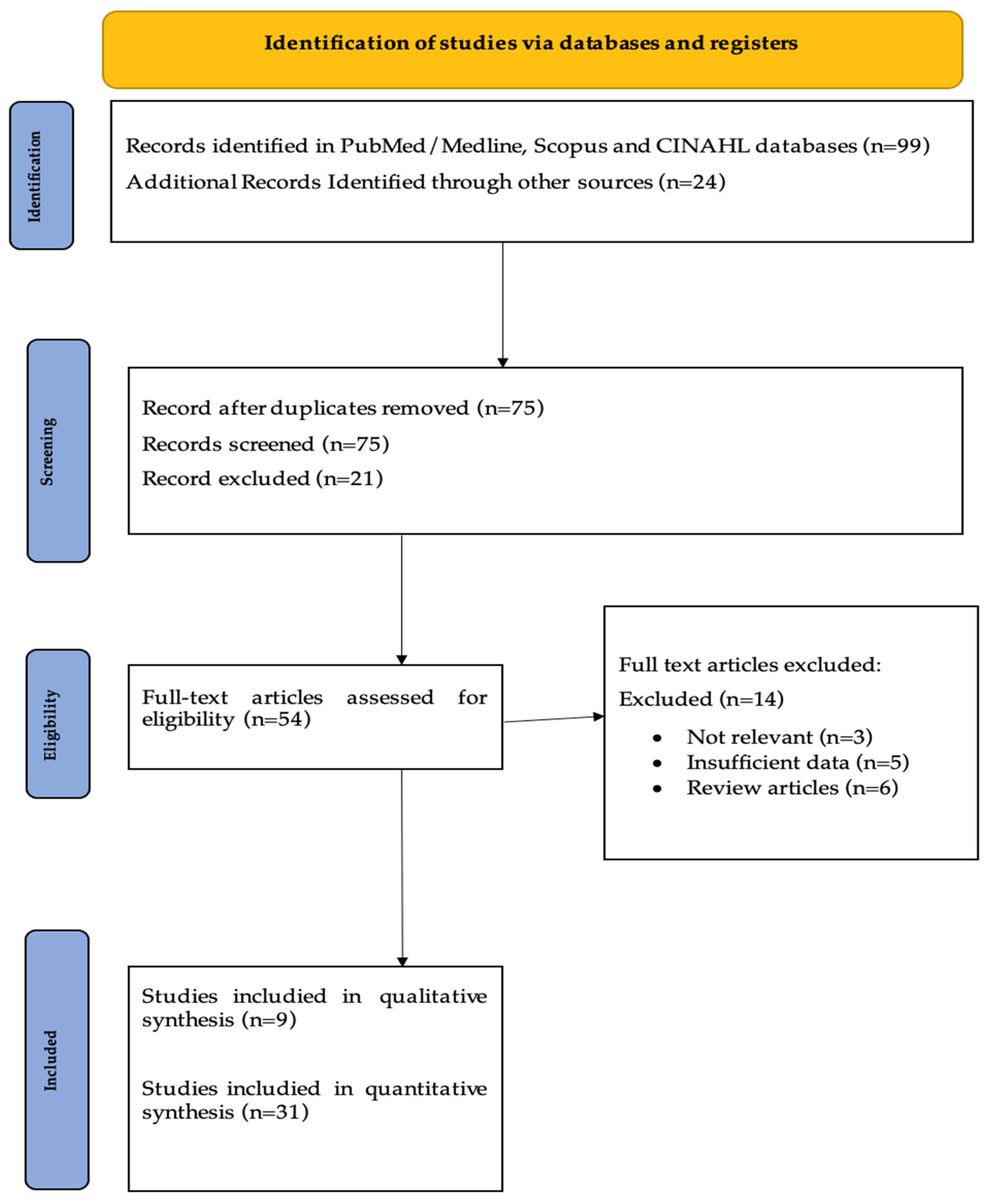

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Information Sources

2.2. Search Strategy

- PubMed:

- Scopus:

- CINAHL:

2.3. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

2.4. PICO-Based Research Question and Eligibility Criteria

2.5. Study Selection Process

2.6. Data Extraction and Analysis

2.7. Thematic Analysis

3. Results

Critical Appraisal of Included Studies

4. Discussion

5. Limitations

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Public Involvement Statement

Guidelines and Standards Statement

Use of Artificial Intelligence

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ayudiah, F.; Putri, Y.; Sulastri, M. Informed Consent in Midwifery: Bridging Legal Requirements and Patient Communication. J. Curr. Health Sci. 2024, 4, 25–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barry, M.J.; Edgman-Levitan, S. Shared decision making--pinnacle of patient-centered care. N. Engl. J. Med. 2012, 366, 780–781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanders, R.A.; Crozier, K. How do informal information sources influence women’s decision-making for birth? A meta-synthesis of qualitative studies. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2018, 18, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Regan, M.; McElroy, K.G.; Moore, K. Choice? Factors That Influence Women’s Decision Making for Childbirth. J. Perinat. Educ. 2013, 22, 171–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Hanson, M.A.; Bardsley, A.; De-Regil, L.M.; Moore, S.E.; Oken, E.; Poston, L.; Ma, R.C.; McAuliffe, F.M.; Maleta, K.; Purandare, C.N.; et al. The International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics (FIGO) recommendations on adolescent, preconception, and maternal nutrition: “Think Nutrition First”. Int. J. Gynaecol. Obstet. 2015, 131 (Suppl. S4), S213–S253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nunes, R. Healthcare as a Universal Human Right: Sustainability in Global Health, 1st ed.; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Capron, A.M. Where Did Informed Consent for Research Come From? J. Law. Med. Ethics 2018, 46, 12–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Horn, R.; Hall, A.; Lucassen, A. Ethical considerations in prenatal genomic testing. Best. Pract. Res. Clin. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2024, 97, 102548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaw, P.; Greenstein, D.; Lerch, J.; Clasen, L.; Lenroot, R.; Gogtay, N.; Evans, A.; Rapoport, J.; Giedd, J. Intellectual ability and cortical development in children and adolescents. Nature 2006, 440, 676–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomson, G.; Dykes, F.; Singh, G.; Cawley, L.; Dey, P. A public health perspective of women’s experiences of antenatal care: An exploration of insights from a community consultation. Midwifery 2013, 29, 211–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hodnett, E.D.; Gates, S.; Hofmeyr, G.J.; Sakala, C. Continuous support for women during childbirth. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2012, 10, CD003766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vedam, S.; Stoll, K.; Taiwo, T.K.; Rubashkin, N.; Cheyney, M.; Strauss, N.; McLemore, M.; Cadena, M.; Nethery, E.; Rushton, E.; et al. The Giving Voice to Mothers study: Inequity and mistreatment during pregnancy and childbirth in the United States. Reprod. Health 2019, 16, 77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vedam, S.; Stoll, K.; McRae, D.N.; Korchinski, M.; Velasquez, R.; Wang, J.; Partridge, S.; McRae, L.; Martin, R.E.; Jolicoeur, G.; et al. Patient-led decision making: Measuring autonomy and respect in Canadian maternity care. Patient Educ. Couns. 2019, 102, 586–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vedam, S.; Stoll, K.; Martin, K.; Rubashkin, N.; Partridge, S.; Thordarson, D.; Jolicoeur, G.; Changing Childbirth in, B.C.S.C. The Mother’s Autonomy in Decision Making (MADM) scale: Patient-led development and psychometric testing of a new instrument to evaluate experience of maternity care. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0171804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heaman, M.I.; Sword, W.A.; Akhtar-Danesh, N.; Bradford, A.; Tough, S.; Janssen, P.A.; Young, D.C.; Kingston, D.A.; Hutton, E.K.; Helewa, M.E. Quality of prenatal care questionnaire: Instrument development and testing. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2014, 14, 188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caron-Flinterman, J.F.; Broerse, J.E.; Bunders, J.F. The experiential knowledge of patients: A new resource for biomedical research? Soc. Sci. Med. 2005, 60, 2575–2584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murugesu, L.; Damman, O.C.; Derksen, M.E.; Timmermans, D.R.M.; de Jonge, A.; Smets, E.M.A.; Fransen, M.P. Women’s Participation in Decision-Making in Maternity Care: A Qualitative Exploration of Clients’ Health Literacy Skills and Needs for Support. Int. J. Env. Res. Public. Health 2021, 18, 1130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, J.M.; Baston, H.A. Feeling in control during labor: Concepts, correlates, and consequences. Birth 2003, 30, 235–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warren, C.; Njuki, R.; Abuya, T.; Ndwiga, C.; Maingi, G.; Serwanga, J.; Mbehero, F.; Muteti, L.; Njeru, A.; Karanja, J.; et al. Study protocol for promoting respectful maternity care initiative to assess, measure and design interventions to reduce disrespect and abuse during childbirth in Kenya. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2013, 13, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nijagal, M.A.; Wissig, S.; Stowell, C.; Olson, E.; Amer-Wahlin, I.; Bonsel, G.; Brooks, A.; Coleman, M.; Devi Karalasingam, S.; Duffy, J.M.N.; et al. Standardized outcome measures for pregnancy and childbirth, an ICHOM proposal. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2018, 18, 953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lukasse, M.; Schroll, A.M.; Karro, H.; Schei, B.; Steingrimsdottir, T.; Van Parys, A.S.; Ryding, E.L.; Tabor, A.; Bidens Study, G. Prevalence of experienced abuse in healthcare and associated obstetric characteristics in six European countries. Acta Obstet. Gynecol. Scand. 2015, 94, 508–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Connor, A.M.; Bennett, C.L.; Stacey, D.; Barry, M.; Col, N.F.; Eden, K.B.; Entwistle, V.A.; Fiset, V.; Holmes-Rovner, M.; Khangura, S.; et al. Decision aids for people facing health treatment or screening decisions. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2009, CD001431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, S.R.; Choi, P.Y.; Henshaw, C.A.; Tree, J. ‘I felt as though I’d been in jail’: Women’s experiences of maternity care during labour, delivery and the immediate postpartum. Fem. Psychol. 2005, 15, 315–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joo, J.Y.; Liu, M.F. Culturally tailored interventions for ethnic minorities: A scoping review. Nurs. Open 2021, 8, 2078–2090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creedy, D.K.; Shochet, I.M.; Horsfall, J. Childbirth and the development of acute trauma symptoms: Incidence and contributing factors. Birth 2000, 27, 104–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvarez, M.; Hotton, E.J.; Harding, S.; Ives, J.; Crofts, J.F.; Wade, J. Women’s and midwives’ views on the optimum process for informed consent for research in a feasibility study involving an intrapartum intervention: A qualitative study. Pilot. Feasibility Stud. 2023, 9, 98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kruske, S.; Young, K.; Jenkinson, B.; Catchlove, A. Maternity care providers’ perceptions of women’s autonomy and the law. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2013, 13, 84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Declercq, E.R.; Sakala, C.; Corry, M.P.; Applebaum, S.; Herrlich, A. Listening to Mothers SM III. New Mothers Speak Out; Childbirth Connections: New York, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Shay, L.A.; Lafata, J.E. Where is the evidence? A systematic review of shared decision making and patient outcomes. Med. Decis. Mak. 2015, 35, 114–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Neill, O. Some limits of informed consent. J. Med. Ethics 2003, 29, 4–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kruk, M.E.; Kujawski, S.; Mbaruku, G.; Ramsey, K.; Moyo, W.; Freedman, L.P. Disrespectful and abusive treatment during facility delivery in Tanzania: A facility and community survey. Health Policy Plan. 2018, 33, e26–e33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bohren, M.A.; Vogel, J.P.; Hunter, E.C.; Lutsiv, O.; Makh, S.K.; Souza, J.P.; Aguiar, C.; Saraiva Coneglian, F.; Diniz, A.L.; Tuncalp, O.; et al. The Mistreatment of Women during Childbirth in Health Facilities Globally: A Mixed-Methods Systematic Review. PLoS Med. 2015, 12, e1001847, discussion e1001847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rawlinson, C.; Carron, T.; Cohidon, C.; Arditi, C.; Hong, Q.N.; Pluye, P.; Peytremann-Bridevaux, I.; Gilles, I. An Overview of Reviews on Interprofessional Collaboration in Primary Care: Barriers and Facilitators. Int. J. Integr. Care 2021, 21, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stacey, D.; Lewis, K.B.; Smith, M.; Carley, M.; Volk, R.; Douglas, E.E.; Pacheco-Brousseau, L.; Finderup, J.; Gunderson, J.; Barry, M.J.; et al. Decision aids for people facing health treatment or screening decisions. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2024, 1, CD001431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shay, L.A.; Lafata, J.E. Understanding patient perceptions of shared decision making. Patient Educ. Couns. 2014, 96, 295–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alkhamees, M.; Alasqah, I. Patient-physician communication in intercultural settings: An integrative review. Heliyon 2023, 9, e22667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schouten, B.C.; Meeuwesen, L. Cultural differences in medical communication: A review of the literature. Patient Educ. Couns. 2006, 64, 21–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kruk, M.E.; Gage, A.D.; Arsenault, C.; Jordan, K.; Leslie, H.H.; Roder-DeWan, S.; Adeyi, O.; Barker, P.; Daelmans, B.; Doubova, S.V.; et al. High-quality health systems in the Sustainable Development Goals era: Time for a revolution. Lancet Glob. Health 2018, 6, e1196–e1252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Legare, F.; Adekpedjou, R.; Stacey, D.; Turcotte, S.; Kryworuchko, J.; Graham, I.D.; Lyddiatt, A.; Politi, M.C.; Thomson, R.; Elwyn, G.; et al. Interventions for increasing the use of shared decision making by healthcare professionals. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2018, 7, CD006732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Idris, I.B.; Hamis, A.A.; Bukhori, A.B.M.; Hoong, D.C.C.; Yusop, H.; Shaharuddin, M.A.; Fauzi, N.; Kandayah, T. Women’s autonomy in healthcare decision making: A systematic review. BMC Womens Health 2023, 23, 643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dixon, J. Improving the quality of care in health systems: Towards better strategies. Isr. J. Health Policy Res. 2021, 10, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fredriksson, M.; Holmstrom, I.K.; Hoglund, A.T.; Fleron, E.; Mattebo, M. Caesarean section on maternal request: A qualitative study of conflicts related to shared decision-making and person-centred care in Sweden. Reprod. Health 2024, 21, 97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baslam, A.; Merrou, S.; Azraida, H.; Belghali, M.Y.; Ouzennou, N.; Marfak, A. Factors Associated with Perinatal Mortality in Pregnant Women in Marrakech: Case Control Study. Acad. J. Health Sci. Med. Balear. 2023, 38, 50–56. [Google Scholar]

- Rowland, L.; Jones, C. Research midwives: Importance and practicalities. Br. J. Midwifery 2013, 21, 60–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shiyanbola, O.O.; Wen, M.J.; Maurer, M.A. Incorporating health literacy principles into the adaptation of a methods motivational interviewing approach for enrolling black adults in a pilot randomized trial. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 4833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mancin, S.; Sguanci, M.; Andreoli, D.; Soekeland, F.; Anastasi, G.; Piredda, M.; De Marinis, M.G. Systematic review of clinical practice guidelines and systematic reviews: A method for conducting comprehensive analysis. MethodsX 2024, 12, 102532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicholls, J.; David, A.L.; Iskaros, J.; Lanceley, A. Patient-centred consent in women’s health: Does it really work in antenatal and intra-partum care? BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2022, 22, 156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Handtke, O.; Schilgen, B.; Mosko, M. Culturally competent healthcare—A scoping review of strategies implemented in healthcare organizations and a model of culturally competent healthcare provision. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0219971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Twimukye, A.; Nabukenya, S.; Kawuma, A.N.; Bayigga, J.; Nakijoba, R.; Asiimwe, S.P.; Byenume, F.; Ojara, F.W.; Waitt, C. ‘Some parts of the consent form are written using complex scientific language’: Community perspectives on informed consent for research with pregnant and lactating mothers in Uganda. BMC Med. Ethics 2024, 25, 149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vandecasteele, R.; Robijn, L.; Willems, S.; De Maesschalck, S.; Stevens, P.A.J. Barriers and facilitators to culturally sensitive care in general practice: A reflexive thematic analysis. BMC Prim. Care 2024, 25, 381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vaswani, V.; Saxena, A.; Shah, S.K.; Palacios, R.; Rid, A. Informed consent for controlled human infection studies in low- and middle-income countries: Ethical challenges and proposed solutions. Bioethics 2020, 34, 809–818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| PICO Element | Inclusion Criteria | Exclusion Criteria |

|---|---|---|

| Population (P) | Pregnant women in perinatal care settings (prenatal, intrapartum, postpartum); all ages and parities. Studies with mixed populations included only if data specific to pregnant women can be extracted. | Non-pregnant individuals; non-human studies; pediatric or non-maternal care; studies where pregnant women’s data are not separable. |

| Intervention (I) | Studies addressing informed consent in maternity care using tools (e.g., MADM, MOR); shared decision-making. | No relevance to informed consent; general ethics without maternity focus. |

| Comparator (C) | Usual care or non-structured consent protocols as baseline. | No comparator; non-empirical opinion articles. |

| Outcomes (O) | Autonomy, satisfaction, PTSD, mistreatment, frequency of interventions. | No patient-centered outcomes; purely technical/clinical results. |

| Criteria | Inclusion | Exclusion |

|---|---|---|

| Study | Qualitative, quantitative (cross-sectional, cohort), systematic reviews | Case reports, editorials, abstracts without full text |

| Language | English | Other languages not translated |

| Data Range | 2000–2025 | Outside 2000–2025 range |

| Study | Country | Study Design | Sample | Outcomes | Key Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ayudiah, F. et al. (2024) [1] | Pakistan | Systematic Review | - |

|

|

| Barry, M. J. and Edgman-Levitan, S. (2012) [2] | USA | Perspective | - |

|

|

| Thomson, G. et al. (2013) [10] | USA | Semi-Structured Interviews | 86 |

|

|

| Vedam, S. et al. (2019) [12] | USA | Quantitative Research | 2700 |

|

|

| Vedam, S. et al. (2017) [14] | USA | Quantitative Research | 2514 |

|

|

| Hodnett, E. D. et al. (2012) [11] | USA | Systematic Review | 10,684 |

|

|

| Heaman, MI. et al. (2014) [15] | USA | 80 |

|

| |

| Caron-Flinterman, JF, Broerse, JEW, Bunders, JFG. (2005) [16] | USA | Quantitative Research | 60 |

|

|

| Green, JM, Baston, HA (2003) [18] | USA | Quantitative Research | 1146 |

|

|

| Warren, C. et al. (2013) [19] | Nairobi | Quantitative Research | 12 |

|

|

| Nijagal MA. et al. A. et al. (2018) [20] | USA | Systematic Review | - |

|

|

| Lukasse, M. et al. (2015) [21] | USA | Quantitative Research | 6923 |

|

|

| O’Connor AM. et al. (2009) [22] | USA | Systematic Review | - |

|

|

| Baker, SR. (2015) [23] | USA | Interviews | 24 |

|

|

| Jou, J. et al. (2015) [24] | USA | Quantitative Analysis | 2400 |

|

|

| Creedy, D. et al. (2000) [25] | USA | Quantitative Research | 499 |

|

|

| Kruske, S. et al. (2013) [27] | USA | Quantitative Research | 336 |

|

|

| Declercq, E. R. et al. (2013) [28] | USA | Research Survey | 2400 |

| |

| Shay, LA, Lafata, JE. (2014) [29] | USA | Systematic Review | - |

|

|

| Baker, S. and Precilla, Y. (2005) [23] | USA | Cross-Sectional Survey | 1672 |

|

|

| Alvarez, M, Hotton, EJ, Harding, S, Ives, J, Crofts, JF, Wade, J. (2023) [26] | USA | Interviews | 51 |

|

|

| O’Neill, O. (2003) [30] | USA | Systematic Review | - |

|

|

| Kruk, M. et al. (2014) [31] | Tanzania | Quantitative | 1779 |

|

|

| Bohren, M. A. et al. (2015) [32] | USA | Systematic Review | - |

|

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kokkosi, E.; Stavros, S.; Moustakli, E.; Vedam, S.; Potiris, A.; Mavrogianni, D.; Antonakopoulos, N.; Panagopoulos, P.; Drakakis, P.; Gourounti, K.; et al. Informed Consent in Perinatal Care: Challenges and Best Practices in Obstetric and Midwifery-Led Models. Nurs. Rep. 2025, 15, 273. https://doi.org/10.3390/nursrep15080273

Kokkosi E, Stavros S, Moustakli E, Vedam S, Potiris A, Mavrogianni D, Antonakopoulos N, Panagopoulos P, Drakakis P, Gourounti K, et al. Informed Consent in Perinatal Care: Challenges and Best Practices in Obstetric and Midwifery-Led Models. Nursing Reports. 2025; 15(8):273. https://doi.org/10.3390/nursrep15080273

Chicago/Turabian StyleKokkosi, Eriketi, Sofoklis Stavros, Efthalia Moustakli, Saraswathi Vedam, Anastasios Potiris, Despoina Mavrogianni, Nikolaos Antonakopoulos, Periklis Panagopoulos, Peter Drakakis, Kleanthi Gourounti, and et al. 2025. "Informed Consent in Perinatal Care: Challenges and Best Practices in Obstetric and Midwifery-Led Models" Nursing Reports 15, no. 8: 273. https://doi.org/10.3390/nursrep15080273

APA StyleKokkosi, E., Stavros, S., Moustakli, E., Vedam, S., Potiris, A., Mavrogianni, D., Antonakopoulos, N., Panagopoulos, P., Drakakis, P., Gourounti, K., Iliadou, M., & Sarella, A. (2025). Informed Consent in Perinatal Care: Challenges and Best Practices in Obstetric and Midwifery-Led Models. Nursing Reports, 15(8), 273. https://doi.org/10.3390/nursrep15080273