Hearing Loss in Young and Middle-Aged Adults as a Modifiable Risk Factor for Late-Life Dementia: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data Sources and Searches

2.2. Study Selection

2.2.1. Population

2.2.2. Exposure

2.2.3. Comparison

2.2.4. Outcome

2.2.5. Study Designs

2.3. Data Extraction

2.4. Risk of Bias Assessment

2.5. Data Synthesis

3. Results

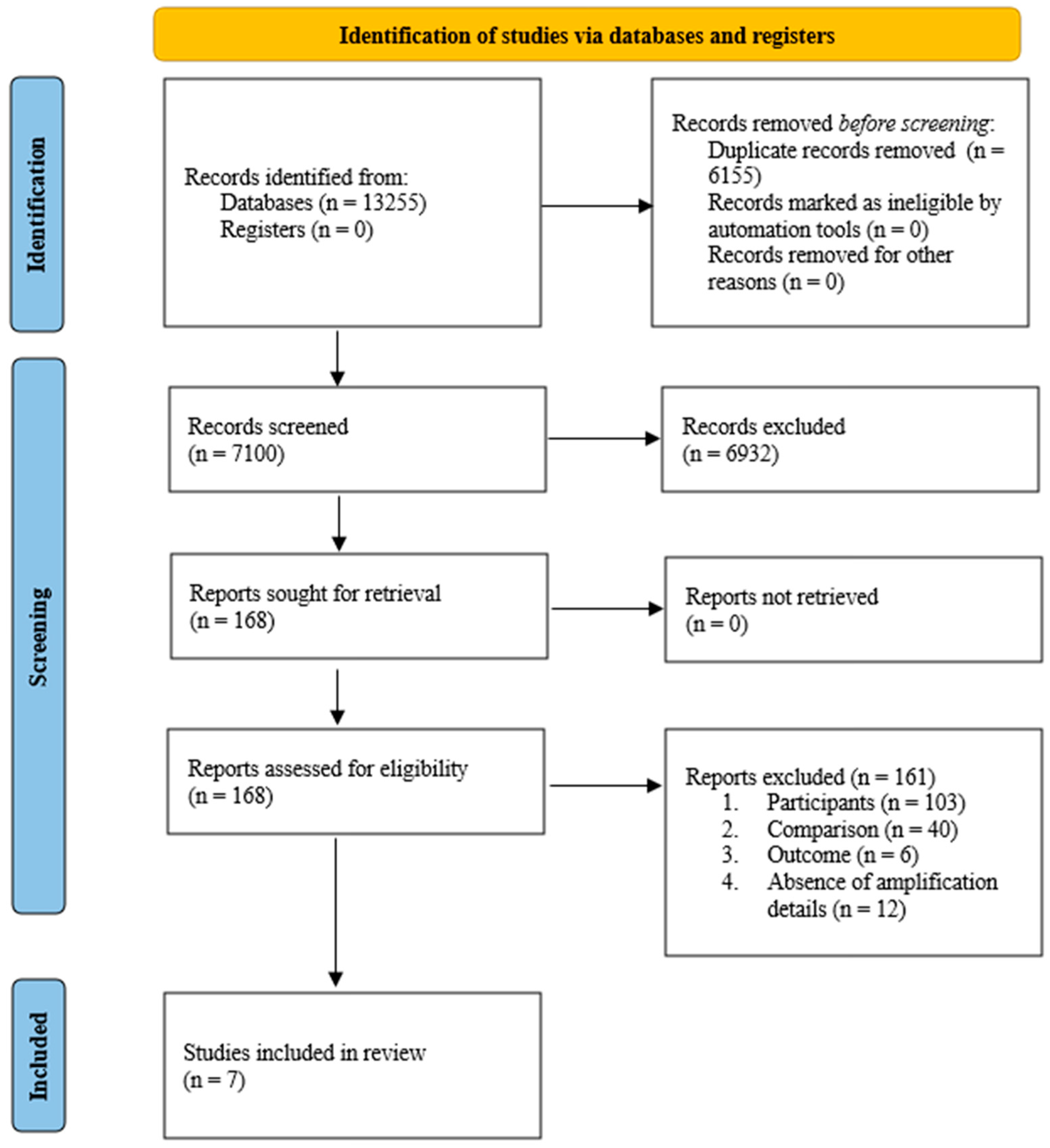

3.1. Study Selection and Characteristics

3.2. Risk of Bias Assessment

3.3. Narrative Synthesis

3.3.1. Population

3.3.2. Cognitive Domains and Outcomes

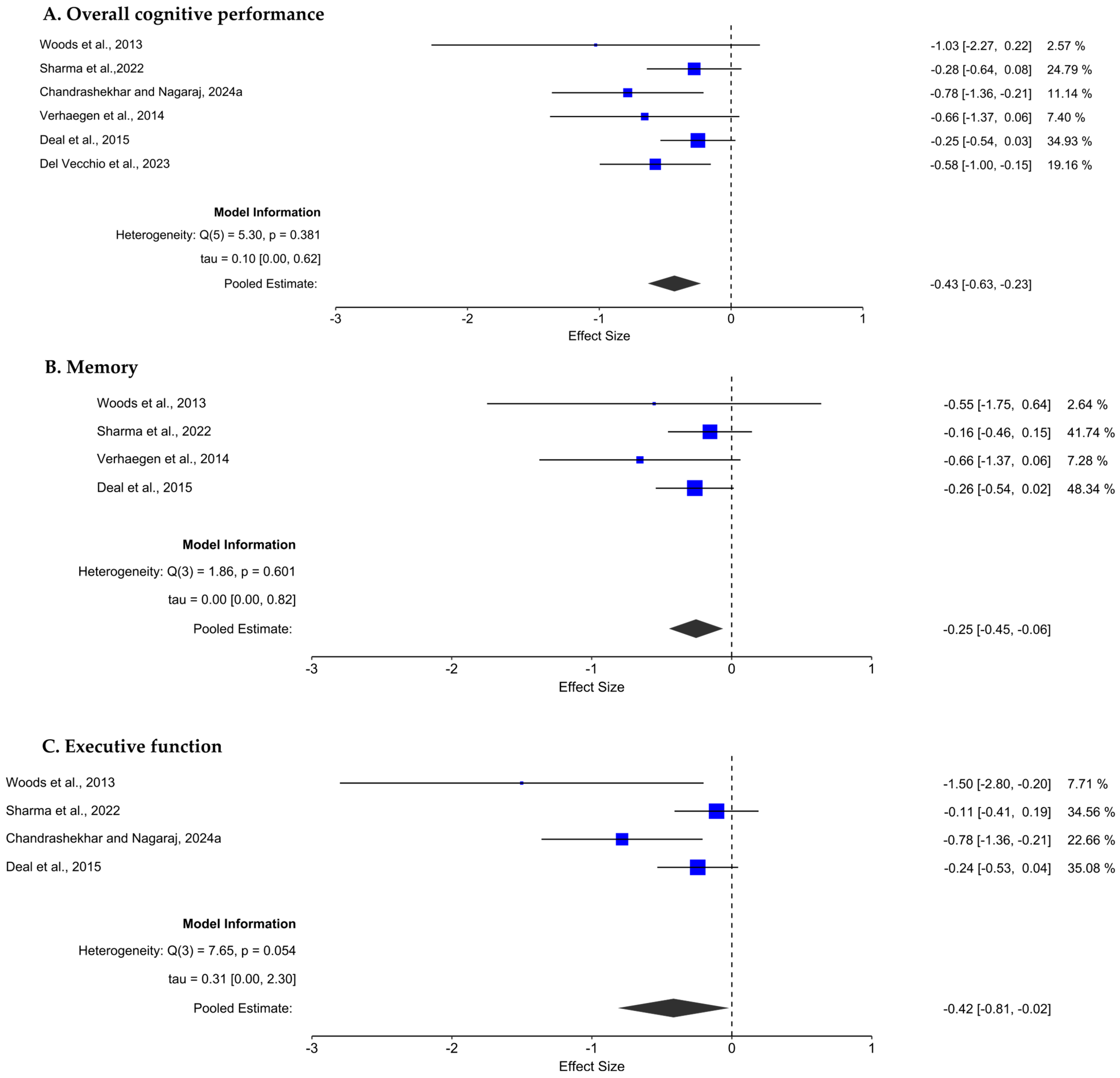

3.4. Meta-Analysis

3.4.1. Effect of Hearing Loss on Overall Cognitive Performance

3.4.2. Effect of Hearing Loss on Memory

3.4.3. Effect of Hearing Loss on Executive Function

3.5. Sensitivity Analysis

4. Discussion

4.1. Effect of Hearing Loss on Memory

4.2. Effect of Hearing Loss on Executive Function

4.3. Effect of Hearing Loss on Global Cognition

4.4. Effect of Hearing Loss on Attention

4.5. Limitations of the Study

4.6. Future Implications

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| PRISMA | Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses |

| PECOS | Population, Exposure, Comparison, Outcome, and Study design |

| PROSPERO | Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews |

| TMT | Trail Making Test |

| JBI | Joanna Briggs Institute |

| MMSE | Mini-Mental State Examination |

| MoCA | Montreal Cognitive Assessment |

| RAVLT | Rey Auditory Verbal Learning Test |

Appendix A

| Database | Search String |

|---|---|

| Pubmed | ((“young*”[Text Word] OR “middle aged”[Text Word] OR “midlife”[Text Word] OR “adult*” [Text Word]) AND (“hearing loss”[Title/Abstract] OR “hearing impairment”[Title/Abstract]) AND (“cogniti*”[Title/Abstract] OR “memory”[Title/Abstract] OR “executive function”[Title/Abstract] OR “verbal fluency”[Title/Abstract] OR “processing speed”[Title/Abstract])) AND ((humans[Filter]) AND (english[Filter])) |

| Scopus | (TITLE-ABS-KEY (((“young*” OR “middle-aged” OR “midlife” OR “adult”) AND (“hearing loss” OR “hearing impairment”) AND (“cogniti*” OR “memory” OR “executive function” OR “attention” OR “verbal fluency” OR “processing speed”)))) AND (LIMIT-TO (SUBJAREA, “MEDI”) OR LIMIT-TO (SUBJAREA, “NEUR”) OR LIMIT-TO (SUBJAREA, “HEAL”) OR LIMIT-TO (SUBJAREA, “PSYC”)) AND (LIMIT-TO (DOCTYPE, “ar”)) AND (LIMIT-TO (LANGUAGE, “English”)) |

| Web of Science | TS = (((“young*” OR “middle aged” OR “midlife” OR “adult*”) AND (“hearing loss” OR “hearing impairment”) AND (“cogniti*” OR “memory” OR “executive function” OR “attention” OR “verbal fluency” OR “processing speed”))) and English (Languages) and Article (Document Types) and English (Languages) |

| Embase | (‘young*’:ti,ab,kw OR ‘middle aged’:ti,ab,kw OR ‘midlife’:ti,ab,kw OR ‘adult*’:ti,ab,kw) AND (‘hearing loss’:ti,ab,kw OR ‘hearing impairment’:ti,ab,kw) AND (‘cognition’:ti,ab,kw OR ‘cognitive’:ti,ab,kw OR ‘memory’:ti,ab,kw OR ‘executive function’:ti,ab,kw OR ‘attention’:ti,ab,kw OR ‘verbal fluency’:ti,ab,kw OR ‘processing speed’:ti,ab,kw) |

Appendix B

| Study Omitted | Pooled Sample Size | Estimate | 95% Confidence Interval | I2 (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower Limits | Upper Limits | ||||

| Del Vecchio et al. [33] | 524 | −0.392 | −0.613 | −0.171 | 11.28 |

| Deal et al. [4] | 383 | −0.524 | −0.772 | −0.276 | 9.43 |

| Verhaegen et al. [34] | 604 | −0.411 | −0.621 | −0.202 | 15.42 |

| Chandrashekhar and Nagaraj [36] | 586 | −0.369 | −0.557 | −0.181 | 0 |

| Sharma et al. [35] | 461 | −0.512 | −0.785 | 0.238 | 28.68 |

| Woods et al. [32] | 622 | −0.409 | −0.606 | −0.212 | 11.54 |

| Study Omitted | Pooled Sample Size | Estimate | 95% Confidence Interval | I2 (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower Limits | Upper Limits | ||||

| Deal et al. [4] | 221 | −0.301 | −0.672 | −0.070 | 19.59 |

| Verhaegen et al. [34] | 442 | −0.223 | −0.424 | −0.022 | 0 |

| Sharma et al. [35] | 299 | −0.326 | −0.580 | 0.072 | 0 |

| Woods et al. [32] | 460 | −0.246 | −0.443 | −0.050 | 0.002 |

| Study Omitted | Pooled Sample Size | Estimate | 95% Confidence Interval | I2 (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower Limits | Upper Limits | ||||

| Deal et al. [4] | 239 | −0.614 | −1.319 | −0.092 | 74.40 |

| Chandrashekhar and Nagaraj [36] | 442 | −0.212 | −0.418 | −0.007 | 0 |

| Sharma et al. [35] | 317 | −0.630 | −1.222 | −0.037 | 64.87 |

| Woods et al. [32] | 478 | −0.293 | −0.589 | −0.003 | 50.22 |

References

- World Health Organization. Deafness and Hearing Loss; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2025; Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/deafness-and-hearing-loss (accessed on 25 March 2025).

- Belin, P.; Zatorre, R.J.; Hoge, R.; Evans, A.C.; Pike, B. Event-related fMRI of the auditory cortex. Neuroimage 1999, 10, 417–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, C.G.; Rapport, L.J.; Billings, B.A.; Ramachandran, V.; Stach, B.A. Hearing loss and verbal memory assessment among older adults. Neuropsychology 2019, 33, 47–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deal, J.A.; Sharrett, A.R.; Albert, M.S.; Coresh, J.; Mosley, T.H.; Knopman, D.; Wruck, L.M.; Lin, F.R. Hearing Impairment and Cognitive Decline: A Pilot Study Conducted Within the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities Neurocognitive Study. Am. J. Epidemiol. 2015, 181, 680–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uhlmann, R.F.; Teri, L.; Rees, T.S.; Mozlowski, K.J.; Larson, E.B. Impact of Mild to Moderate Hearing Loss on Mental Status Testing. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 1989, 37, 223–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wayne, R.V.; Johnsrude, I.S. A review of causal mechanisms underlying the link between age-related hearing loss and cognitive decline. Ageing Res. Rev. 2015, 23 Pt B, 154–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Powell, D.S.; Oh, E.S.; Lin, F.R.; Deal, J.A. Hearing Impairment and Cognition in an Aging World. J. Assoc. Res. Otolaryngol. 2021, 22, 387–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Loughrey, D.G.; Kelly, M.E.; Kelley, G.A.; Brennan, S.; Lawlor, B.A. Association of Age-Related Hearing Loss With Cognitive Function, Cognitive Impairment, and Dementia: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. JAMA Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 2018, 144, 115–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, R.C.; Proctor, D.; Soni, J.; Pikett, L.; Livingston, G.; Lewis, G.; Schilder, A.; Bamiou, D.; Mandavia, R.; Omar, R.; et al. Adult-onset hearing loss and incident cognitive impairment and dementia—A systematic review and meta-analysis of cohort studies. Ageing Res. Rev. 2024, 98, 102346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Verma, R.R.; Konkimalla, A.; Thakar, A.; Sikka, K.; Singh, A.C.; Khanna, T. Prevalence of hearing loss in India. Natl. Med. J. India 2022, 34, 216–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferguson, M.A.; Nakano, K.; Jayakody, D.M.P. Clinical Assessment Tools for the Detection of Cognitive Impairment and Hearing Loss in the Ageing Population: A Scoping Review. Clin. Interv. Aging 2023, 18, 2041–2051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Livingston, G.; Sommerlad, A.; Orgeta, V.; Costafreda, S.G.; Huntley, J.; Ames, D.; Ballard, C.; Banerjee, S.; Burns, A.; Cohen-Mansfield, J.; et al. Dementia prevention, intervention, and care. Lancet 2017, 390, 2673–2734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sperling, R.A.; Aisen, P.S.; Beckett, L.A.; Bennett, D.A.; Craft, S.; Fagan, A.M.; Iwatsubo, T.; Jack, C.R., Jr.; Kaye, J.; Montine, T.J.; et al. Toward defining the preclinical stages of Alzheimer’s disease: Recommendations from the National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer’s Association workgroups on diagnostic guidelines for Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimer’s Dement. 2011, 7, 280–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osler, M.; Christensen, G.T.; Mortensen, E.L.; Christensen, K.; Garde, E.; Rozing, M.P. Hearing loss, cognitive ability, and dementia in men age 19–78 years. Eur. J. Epidemiol. 2019, 34, 125–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, C.M.; Lee, C.T.C. Association of Hearing Loss With Dementia. JAMA Netw. Open 2019, 2, e198112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roy, R.A. Auditory Working Memory: A Comparison Study in Adults with Normal Hearing and Mild to Moderate Hearing Loss. Glob. J. Otolaryngol. 2018, 13, 67–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agrawal, D.; Malo, P.K.; Singh, S.; Issac, T.G. Hearing loss and its relation to cognition in Indian cohort: A behavioral and neuroimaging study. Alzheimer’s Dement. 2025, 17, e70106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Livingston, G.; Huntley, J.; Liu, K.Y.; Costafreda, S.G.; Selbæk, G.; Alladi, S.; Ames, D.; Banerjee, S.; Burns, A.; Brayne, C.; et al. Dementia prevention, intervention, and care: 2024 report of the Lancet standing Commission. Lancet 2024, 404, 572–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taljaard, D.S.; Olaithe, M.; Brennan-Jones, C.G.; Eikelboom, R.H.; Bucks, R.S. The relationship between hearing impairment and cognitive function: A meta-analysis in adults. Clin. Otolaryngol. 2016, 41, 718–729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, F.R.; Yaffe, K.; Xia, J.; Xue, Q.-L.; Harris, T.B.; Purchase-Helzner, E.; Satterfield, S.; Ayonayon, H.N.; Ferrucci, L.; Simonsick, E.M.; et al. Hearing loss and cognitive decline in older adults. JAMA Intern. Med. 2013, 173, 293–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dawes, P.; Cruickshanks, K.J.; Fischer, M.E.; Klein, B.E.K.; Klein, R.; Nondahl, D.M. Hearing-aid use and long-term health outcomes: Hearing handicap, mental health, social engagement, cognitive function, physical health, and mortality. Int. J. Audiol. 2015, 54, 838–844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Glick, H.A.; Sharma, A. Cortical Neuroplasticity and Cognitive Function in Early-Stage, Mild-Moderate Hearing Loss: Evidence of Neurocognitive Benefit From Hearing Aid Use. Front. Neurosci. 2020, 14, 93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.J. The Relationship between Hearing Impairment and Cognitive Function in Middle-Aged and Older Adults: A Meta-Analysis. Commun. Sci. Disord. 2018, 23, 378–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Morais, E.A.; dos Santos, I.B.; Massi, G.; Ravazzi, G.; Marques, C.L.B.; Garcia, A.C.; Magrini, A.M.; Galarza, K.M.; Raignieri, J.; Lacerda, A.; et al. Cognitive Aspects of Adults and Older Adults with Hearing Loss, Users or not of Hearing Aids: A Meta-Analysis. Glob. J. Hum.-Soc. Sci. 2025, 25, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joanna Briggs Institute. Checklist for Analytical Cross Sectional Studies. 2016. Available online: https://jbi.global/critical-appraisal-tools (accessed on 16 February 2025).

- Melo, G.; Dutra, K.L.; Filho, R.R.; Ortega, A.d.O.L.; Porporatti, A.L.; Dick, B.; Flores-Mir, C.; Canto, G.D.L. Association between psychotropic medications and presence of sleep bruxism: A systematic review. J. Oral Rehabil. 2018, 45, 545–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, D.B. Practical Meta-Analysis Effect Size Calculator (Version 2023.11.27). 2023. Available online: https://jbi.global/critical-appraisal-tools (accessed on 6 April 2025).

- Luo, D.; Wan, X.; Liu, J.; Tong, T. Optimally estimating the sample mean from the sample size, median, mid-range, and/or mid-quartile range. Stat. Methods Med. Res. 2018, 27, 1785–1805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- JASP Team. JASP (Version 0.19.3). JASP—Free and User-Friendly Statistical Software. 2025. Available online: https://jasp-stats.org/ (accessed on 25 April 2025).

- Higgins, J.P.; Thompson, S.G.; Deeks, J.J.; Altman, D.G. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ 2003, 327, 557–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellis, P.D. The Essential Guide to Effect Sizes: Statistical Power, Meta-Analysis and the Interpretation of Research Results; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woods, W.S.; Kalluri, S.; Pentony, S.; Nooraei, N. Predicting the effect of hearing loss and audibility on amplified speech reception in a multitalker listening scenario. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 2013, 133, 4268–4278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Vecchio, V.; Tricarico, L.; Pisani, A.; Serra, N.; D’errico, D.; De Corso, E.; Rea, T.; Picciotti, P.M.; Laria, C.; Manna, G.; et al. Vascular Factors in Patients with Midlife Sensorineural Hearing Loss and the Progression to Mild Cognitive Impairment. Medicina 2023, 59, 481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Verhaegen, C.; Collette, F.; Majerus, S. The impact of aging and hearing status on verbal short-term memory. Neuropsychol. Dev. Cogn. B Aging Neuropsychol. Cogn. 2014, 21, 464–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, A.; Mohanty, M.; Panda, N.; Munjal, S. Impact of Hearing Loss on Cognitive Abilities in Subjects with Tinnitus. Neurol. India 2022, 70, 554–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandrashekar, P.; Nagaraj, H. Executive functions in mid-life adults with mild sensorineural hearing loss compared with age-matched controls with normal hearing. Egypt. J. Otolaryngol. 2024, 40, 85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandrashekar, P.; Nagaraj, H. Verbal Fluency as a Measure of Executive Function in Middle-Aged Adults with Mild Sensorineural Hearing Loss. Indian J. Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 2024, 76, 5443–5450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, F.R.; Ferrucci, L.; Metter, E.J.; An, Y.; Zonderman, A.B.; Resnick, S.M. Hearing Loss and Cognition in the Baltimore Longitudinal Study of Aging. Neuropsychology 2011, 25, 763–770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Powell, D.S.; Oh, E.S.; Reed, N.S.; Lin, F.R.; Deal, J.A. Hearing Loss and Cognition: What We Know and Where We Need to Go. Front. Aging Neurosci. 2022, 13, 769405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Husain, F.T.; Medina, R.E.; Davis, C.W.; Szymko-Bennett, Y.; Simonyan, K.; Pajor, N.M.; Horwitz, B. Neuroanatomical changes due to hearing loss and chronic tinnitus: A combined VBM and DTI study. Brain Res. 2011, 1369, 74–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fortunato, S.; Forli, F.; Guglielmi, V.; De Corso, E.; Paludetti, G.; Berrettini, S.; FetonI, A. A review of new insights on the association between hearing loss and cognitive decline in ageing. ACTA Otorhinolaryngol. Ital. 2016, 36, 155–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diamond, A. Executive functions. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2013, 64, 135–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ellis, R.J.; Molander, P.; Rönnberg, J.; Lyxell, B.; Andersson, G.; Lunner, T. Predicting Speech-in-Noise Recognition From Performance on the Trail Making Test. Ear Hear. 2016, 37, 73–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quittner, A.L.; Leibach, P.; Marciel, K. The Impact of Cochlear Implants on Young Deaf Children. Arch. Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 2004, 130, 547–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Zhu, M.; Qiao, Y.; Sun, W.; Sun, Y.; Long, Y.; Guo, H.; Cai, C.; Shen, H.; Shang, Y. Visual selective attention in individuals with age-related hearing loss. NeuroImage 2024, 298, 120787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Study | Sample Size | Age (in Years), Mean ± SD | Pure Tone Average (dB HL) | Degree of Hearing Loss in HL Group | Cognitive Domains Tests Administered and Findings (‘+’ Indicates the HL Group Performed Significantly Poorer than the NH Group; ‘-’ Indicates the NH Group Performed Significantly Poorer than the HL Group, and ‘=’ Indicates no Significant Difference Between Groups) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Deal et al. [4] | Total = 253 NH = 73 Mild HL = 95 Moderate/severe HL = 85 | NH: 53.8 ± 4 Mild HL: 56.4 ± 4.9 Moderate/severe HL: 59.1 ± 5.4 | NH group 18.1 ± 6.3 HL group Mild HL: 33.2 ± 4.1 Moderate/severe HL: 49.6 ± 8.7 | Mild to moderate | Memory

|

| Woods et al. [32] | Total = 14 NH = 10 HL = 4 | NH: 60 ± 12 HL: 36 ± 14 | NH group RE: 5.4 ± 2.9 LE: 6.5 ± 3.4 HL group RE: 41.3 ± 4.6 LE: 41.2 ± 4.3 | Mild to moderate | Memory

|

| Del Vecchio et al. [33] | Total = 112 NH = 81 HL = 31 | NH: 53.2 ± 4.8 HL: 58 ± 5.2 | NH group RE: 12.5 ± 2.8 LE: 12.4 ± 3.1 HL group RE: 40.2 ± 18.7 LE: 41.2 ± 17.2 | Mild to moderate | Overall cognition

|

| Verhaegen et al. [34] | Total = 32 NH = 16 HL = 16 | NH: 24.2 ± 1.4 HL: 25.2 ± 5.5 | NH group 6.8 ± 3.7 HL group 17.2 ± 6.3 | Minimal | Memory

|

| Sharma et al. [35] | Total = 170 NH = 100 HL = 70 | NH: 37.4 ± 10.1 HL: 43.5 ± 9.7 | NH group RE: 18.7 ± 3.2 LE: 18.9 ± 3.9 HL group PTA1 RE: 34.7 ± 10.5 LE: 37.4 ± 12.4 PTA2 RE: 50.6 + 17.9 LE: 58.2 + 14.5 | Mild to moderate | Memory

|

| Chandrashekhar and Nagaraj [36] | Total = 50 NH = 25 HL = 25 | NH: 49 ± 3.3 HL: 50.4 ± 2.8 | NH group RE: 10.4 ± 4.0 LE: 10.6 ± 3.2 HL group RE: 33.3 ± 4.5 LE: 33.2 ± 4.2 | Mild | Executive function

|

| Chandrashekhar and Nagaraj [37] | Total = 50 NH = 25 HL = 25 | NH: 49 ± 3.3 HL: 50.4 ± 2.8 | NH group RE: 10.4 ± 4.0 LE: 10.6 ± 3.2 HL group RE: 33.2 ± 4.5 LE: 33.2 ± 4.2 | Mild | Executive function

|

| Study | Were the Criteria for Inclusion in the Sample Clearly Defined? | Were the Study Subjects and the Setting Described in Detail? | Was the Exposure Measured in a Valid and Reliable Way? | Were Objective, Standard Criteria Used for Measurement of the Condition? | Were Confounding Factors Identified? | Were Strategies to Deal with Confounding Factors Stated? | Were the Outcomes Measured in a Valid and Reliable Way? | Was Appropriate Statistical Analysis Used? | Overall Appraisal | No. of Yes Responses | Methodological Quality |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Del Vecchio et al. [33] | Yes | Unclear | Yes | Yes | Yes | Unclear | Yes | Yes | Include | 6 | Strong |

| Deal et al. [4] | Unclear | Unclear | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Include | 6 | Strong |

| Verhaegen et al. [34] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Unclear | Yes | Unclear | Yes | Yes | Include | 6 | Strong |

| Chandrashekhar and Nagaraj [36] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Include | 8 | Strong |

| Chandrashekhar and Nagaraj [37] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Include | 8 | Strong |

| Sharma et al. [35] | Yes | Unclear | Yes | Yes | Yes | Unclear | Yes | Yes | Include | 6 | Strong |

| Woods et al. [32] | Yes | Unclear | Yes | Yes | Yes | Unclear | Unclear | Yes | Include | 5 | Moderate |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Satheesan, L.; Shastri, U.; Bajaj, G.; Kalaiah, M.K. Hearing Loss in Young and Middle-Aged Adults as a Modifiable Risk Factor for Late-Life Dementia: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Audiol. Res. 2025, 15, 174. https://doi.org/10.3390/audiolres15060174

Satheesan L, Shastri U, Bajaj G, Kalaiah MK. Hearing Loss in Young and Middle-Aged Adults as a Modifiable Risk Factor for Late-Life Dementia: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Audiology Research. 2025; 15(6):174. https://doi.org/10.3390/audiolres15060174

Chicago/Turabian StyleSatheesan, Lakshmi, Usha Shastri, Gagan Bajaj, and Mohan Kumar Kalaiah. 2025. "Hearing Loss in Young and Middle-Aged Adults as a Modifiable Risk Factor for Late-Life Dementia: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis" Audiology Research 15, no. 6: 174. https://doi.org/10.3390/audiolres15060174

APA StyleSatheesan, L., Shastri, U., Bajaj, G., & Kalaiah, M. K. (2025). Hearing Loss in Young and Middle-Aged Adults as a Modifiable Risk Factor for Late-Life Dementia: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Audiology Research, 15(6), 174. https://doi.org/10.3390/audiolres15060174