Trends and Incidence of Hearing Implant Utilization in Italy: A Population-Based Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

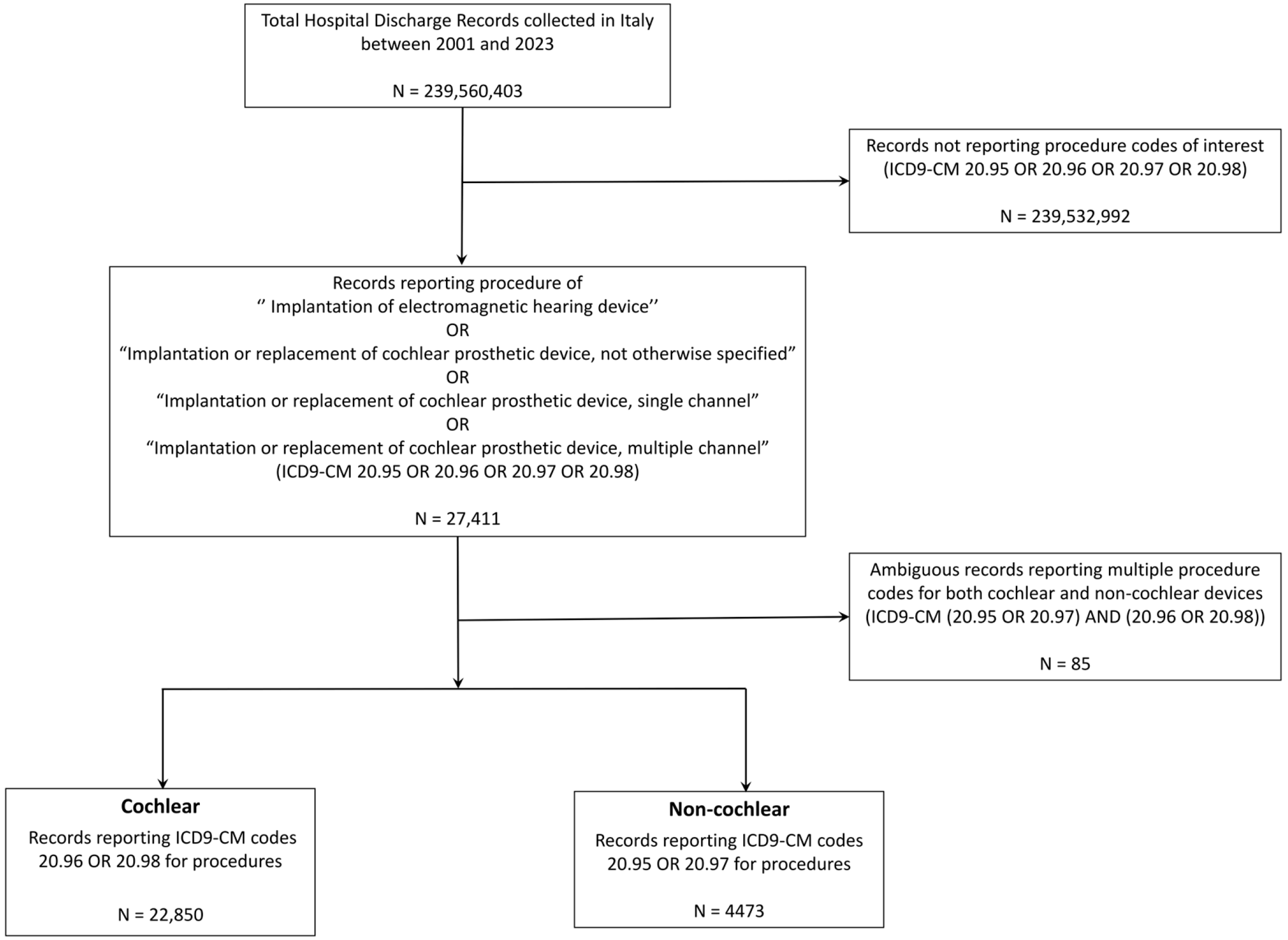

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data Source

2.2. Study Design

2.3. Measures

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Overview

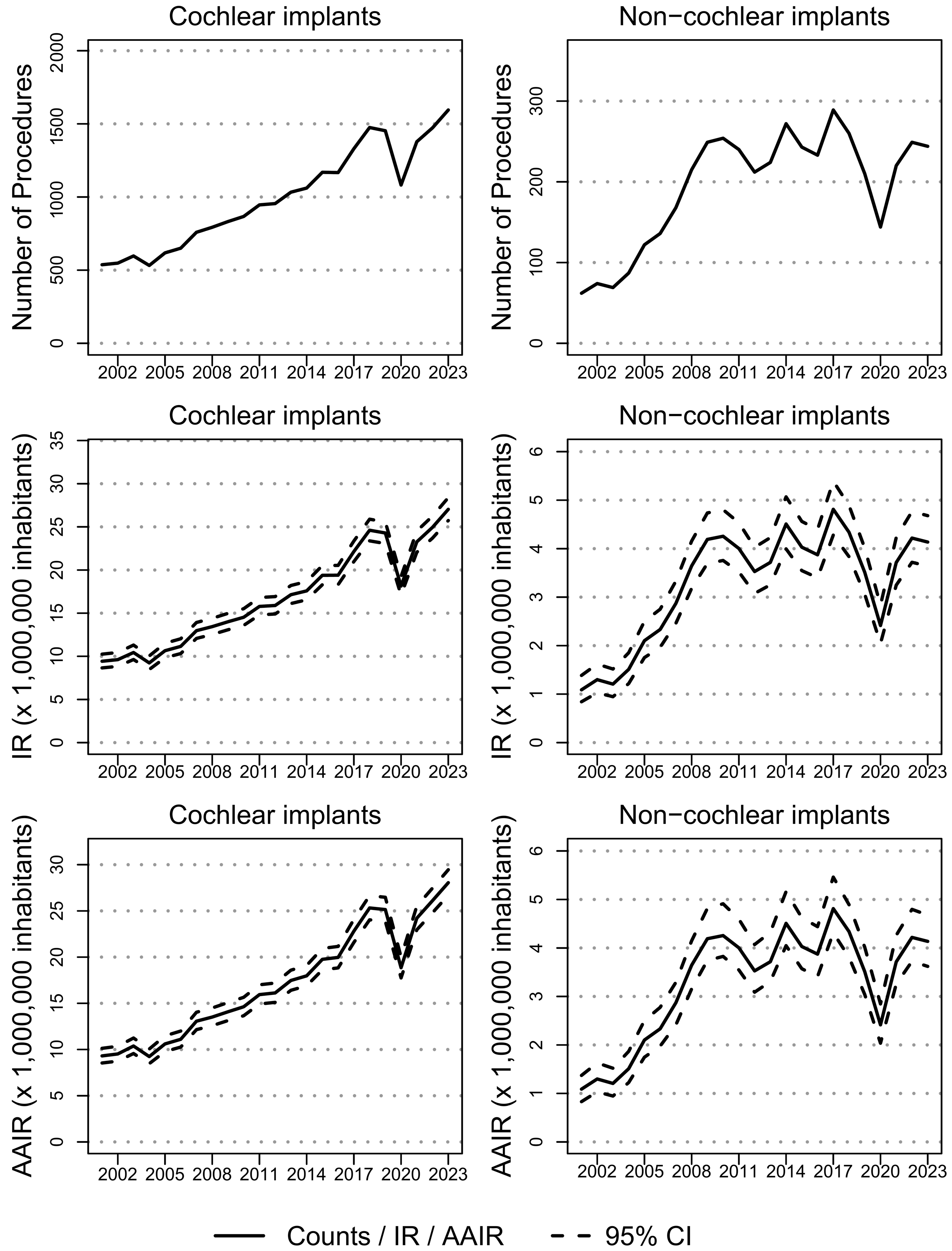

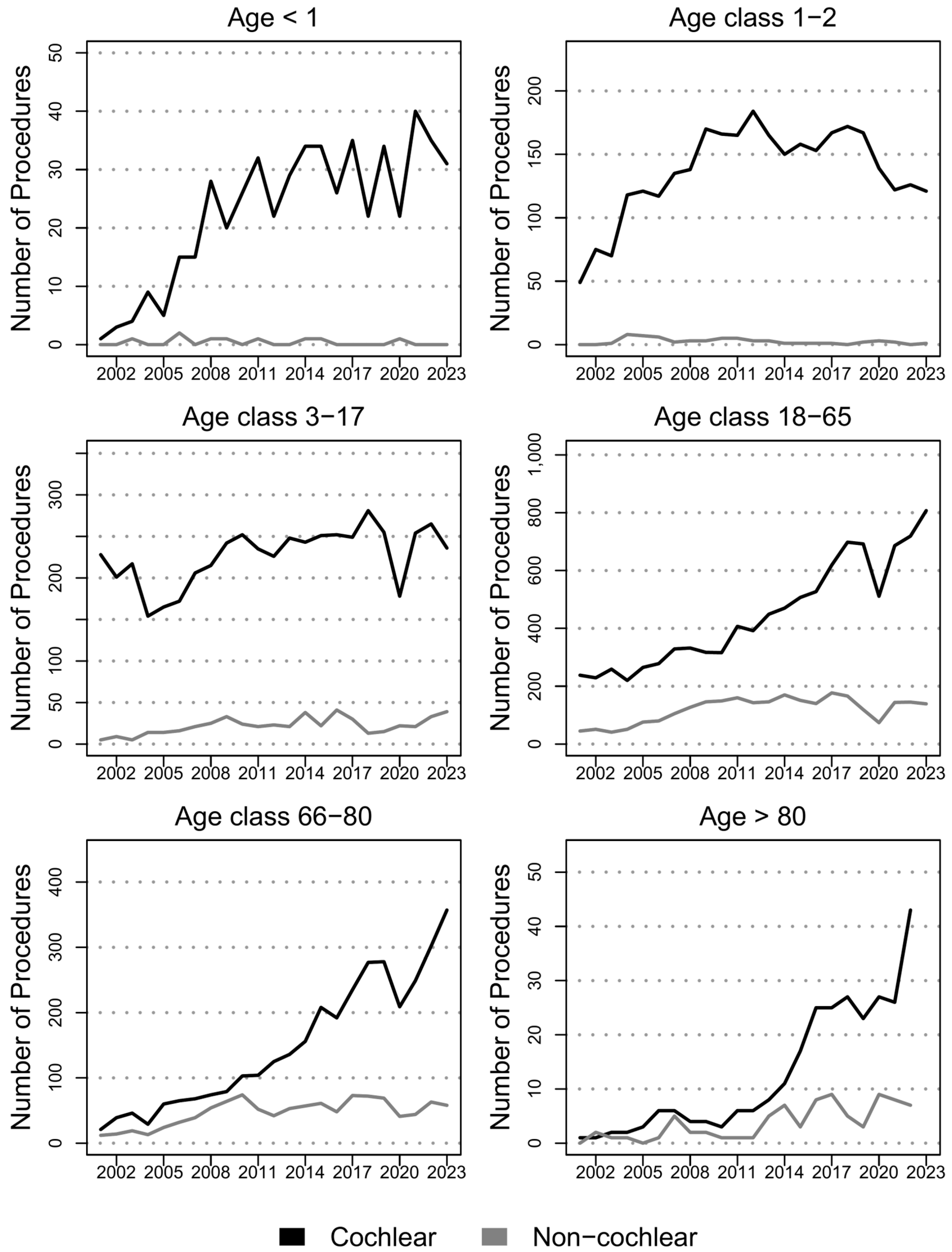

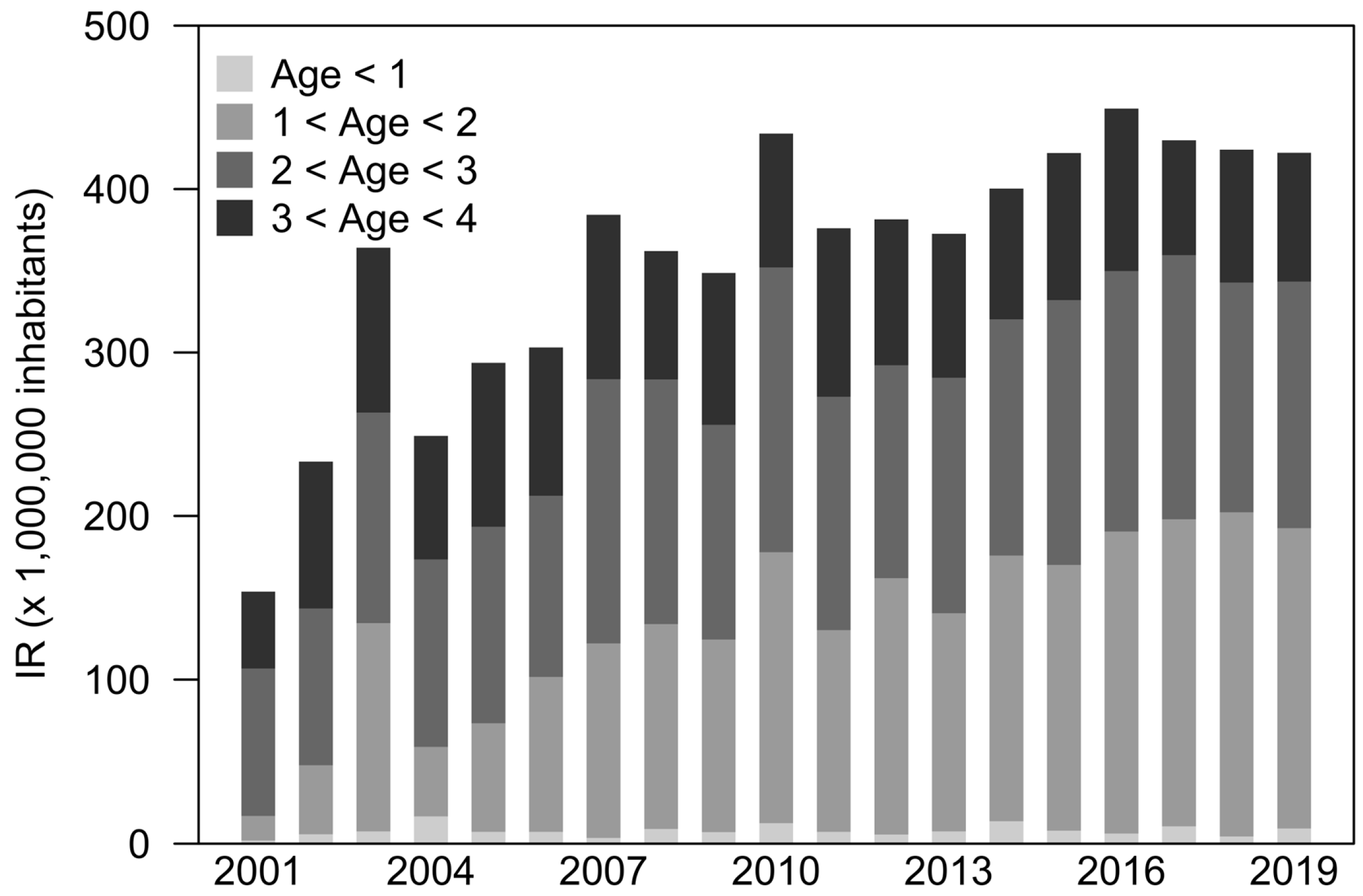

3.2. Cochlear Implants

3.3. Non-Cochlear Implants

4. Discussion

4.1. Cochlear Implants

4.2. Non Cochlear Implants

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| SSD | Single-side deafness |

| HL | Hearing loss |

| CI | Cochlear implant |

| HDR | Hospital discharge record |

| ISS | Istituto Superiore di Sanità—Italian National Institute of Health |

| ICD9-CM | International classification of diseases—clinical modification |

| CI95% | 95% confidence interval |

| IR | Incidence rate |

| AAIR | Age-adjusted incidence rate |

| IRR | Incidence rate ratio |

References

- National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (Great Britain). Cochlear Implants for Children and Adults with Severe to Profound Deafness. National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence. 2009. Available online: www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ta566 (accessed on 30 October 2025).

- Simon, F.; Roman, S.; Truy, E.; Barone, P.; Belmin, J.; Blanchet, C.; Borel, S.; Charpiot, A.; Coez, A.; Deguine, O.; et al. Guidelines (short version) of the French Society of Otorhinolaryngology (SFORL) on pediatric cochlear implant indications. Eur. Ann. Otorhinolaryngol. Head Neck Dis. 2019, 136, 385–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hermann, R.; Lescanne, E.; Loundon, N.; Barone, P.; Belmin, J.; Blanchet, C.; Borel, S.; Charpiot, A.; Coez, A.; Deguine, O.; et al. French Society of ENT (SFORL) guidelines Indications for cochlear implantation in adults. Eur. Ann. Otorhinolaryngol. Head Neck Dis. 2019, 136, 193–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berrettini, S.; Cuda, D.; Minozzi, S.; Artioli, F.; Barbieri, U.; Borghi, C.; Cristofari, E.; Conte, G.; Cornolti, D.; di Lisi, D.; et al. Cochlear implant procedure Italian Clinical Practice Guidelines of the Italian Society of Otorhinolaryngology (SIOeChCF) and Italian Society of Audiology and Phoniatrics (SIAF) Part 1: Cochlear implants in adults. ACTA Otorhinolaryngol. 2025, 45, 47–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cuda, D.; Berrettini, S.; Minozzi, S.; Artioli, F.; Barbieri, U.; Borghi, C.; Cristofari, E.; Conte, G.; Cornolti, D.; di Lisi, D.; et al. Cochlear Implant (CI) procedure Italian Clinical Practice Guidelines of the Italian Society of Otorhinolaryngology (SIOeChCF) and Italian Society of Audiology and Phoniatrics (SIAF) Part 2: Cochlear implants in children. ACTA Otorhinolaryngol. 2025, 45, 124–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bruschini, L.; Canzi, P.; Canale, A.; Covelli, E.; Laborai, A.; Monteforte, M.; Cinquini, M.; Barbara, M.; Beltrame, M.A.; Bovo, R.; et al. Implantable hearing devices in clinical practice Systematic review and consensus statements. ACTA Otorhinolaryngol. 2024, 44, 52–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Raeve, L.; Archbold, S.; Lehnhardt-Goriany, M.; Kemp, T. Prevalence of cochlear implants in Europe: Trend between 2010 and 2016. Cochlear Implant. Int. 2020, 21, 275–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stöver, T.; Plontke, S.K.; Lai, W.K.; Zahnert, T.; Guntinas-Lichius, O.; Welkoborsky, H.J.; Aschendorff, A.; Deitmer, T.; Loth, A.; Lang, S.; et al. The German cochlear implant registry: One year experience and first results on demographic data. Eur. Arch. Oto-Rhino-Laryngol. 2024, 281, 5243–5254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kashio, A.; Takahashi, H.; Nishizaki, K.; Hara, A.; Yamasoba, T.; Moriyama, H. Cochlear implants in Japan: Results of cochlear implant reporting system over more than 30 years. Auris Nasus Larynx 2021, 48, 622–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sorkin, D.L.; Buchman, C.A. Cochlear implant access in six developed countries. Otol. Neurotol. 2016, 37, e161–e164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Humes, L.E. US population data on hearing loss trouble hearing and hearing-device use in adults: National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2011-12 2015-16 and 2017-20. Trends Hear. 2023, 27, 23312165231160978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vandenbroucke, J.P.; von Elm, E.; Altman, D.G.; Gøtzsche, P.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Pocock, S.J.; Poole, C.; Schlesselman, J.J.; Egger, M. Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE): Explanation and Elaboration. Ann. Intern. Med. 2007, 147, W-163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benchimol, E.I.; Smeeth, L.; Guttmann, A.; Harron, K.; Moher, D.; Petersen, I.; Sørensen, H.T.; von Elm, E.; Langan, S.M. The REporting of studies Conducted using Observational Routinely-collected health Data (RECORD) Statement. PLoS Med. 2015, 12, e1001885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministero della Salute Ex-Direzione Generale della Programmazione sanitaria-Ufficio 6. Rapporto Annuale Sull’attività Di ricovero Ospedaliero Dati SDO 2022. 2024. Available online: https://www.salute.gov.it/imgs/C_17_pubblicazioni_3441_allegato.pdf (accessed on 2 December 2025).

- Raine, C. Cochlear implants in the United Kingdom: Awareness and utilization. Cochlear Implant. Int. 2013, 14 (Suppl. 1), S32–S37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliver, J. New expectations: Pediatric cochlear implantation in Japan. Cochlear Implant. Int. 2013, 14 (Suppl. 1), S13–S17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Bruijnzeel, H.; Bezdjian, A.; Lesinski-Schiedat, A.; Illg, A.; Tzifa, K.; Monteiro, L.; della Volpe, A.; Grolman, W.; Topsaka, V. Evaluation of pediatric cochlear implant care throughout Europe: Is European pediatric cochlear implant care performed according to guidelines? Cochlear Implant. Int. 2017, 18, 287–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loth, A.; Vazzana, C.; Leinung, M.; Guderian, D.; Issing, C.; Baumann, U.; Stöver, T. Quality control in cochlear implant therapy: Clinical practice guidelines and registries in European countries. Eur. Arch. Oto-Rhino-Laryngol. 2022, 279, 4779–4786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stöver, T.; Plontke, S.K.; Guntinas-Lichius, O.; Welkoborsky, H.J.; Zahnert, T.; Delank, K.W.; Deitmer, T.; Esser, D.; Dietz, A.; Wienke, A.; et al. Structure and establishment of the German Cochlear Implant Registry (DCIR). Hno 2023, 71, 82–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parent, V.; Codet, M.; Aubry, K.; Bordure, P.; Bozorg-Grayeli, A.; Deguine, O.; Eyermann, C.; Franco-Vidal, V.; Guevara, N.; Karkas, A.; et al. The French Cochlear Implant Registry (EPIIC): Cochlear implantation complications. Eur. Ann. Otorhinolaryngol. Head Neck Dis. 2020, 137, S37–S43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eurostat. Demography of Europe—2023 Edition. 2023. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/web/interactive-publications/demography-2023#about-publication (accessed on 30 October 2025).

- Stöver, T.; Zeh, R.; Gängler, B.; Plontke, S.K.; Ohligmacher, S.; Deitmer, T.; Hupka, O.; Welkoborsky, H.J.; Schulz, M.; Delank, W.; et al. Regional distribution of cochlear implant (CI)-providing institutions in Germany. Laryngo-Rhino-Otol. 2020, 99, 863–871. [Google Scholar]

- Sahin, M.I.; Sagers, J.E.; Stankovic, K.M. Cochlear implantation: Vast unmet need to address deafness globally. Otol. Neurotol. 2017, 38, 786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bruijnzeel, H.; Ziylan, F.; Stegeman, I.; Topsakal, V.; Grolman, W. A Systematic Review to Define the Speech and Language Benefit of Early (<12 Months) Pediatric Cochlear Implantation. Audiol. Neuro-Otol. 2016, 21, 113–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bubbico, L.; Ferlito, S.; Antonelli, G.; Martini, A.; Pescosolido, N. Hearing and Vision Screening Program for newborns in Italy. Ann. Ig. 2021, 33, 433–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wooltorton, E. Cochlear implant recipients at risk for meningitis. Can. Med. Assoc. J. 2002, 167, 670, Erratum in Can. Med. Assoc. J. 2003, 168, 257.. [Google Scholar]

- Josefson, D. Cochlear implants carry risk of meningitis agencies warn. BMJ 2002, 325, 298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lenarz, M.; Sönmez, H.; Joseph, G.; Büchner, A.; Lenarz, T. Cochlear implant performance in geriatric patients. Laryngoscope 2012, 122, 1361–1365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuda, D.; Manrique, M.; Ramos, Á.; Marx, M.; Bovo, R.; Khnifes, R.; Hilly, O.; Belmin, J.; Stripeikyte, G.; Graham, P.L.; et al. Improving quality of life in the elderly: Hearing loss treatment with cochlear implants. BMC Geriatr. 2024, 24, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mosnier, I.; Belmin, J.; Cuda, D.; Manrique Huarte, R.; Marx, M.; Ramos Macias, A.; Khnifes, R.; Hilly, O.; Bovo, R.; James, C.J.; et al. Cognitive processing speed improvement after cochlear implantation. Front. Aging Neurosci. 2024, 16, 1444330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsai Do, B.S.; Bush, M.L.; Weinreich, H.M.; Schwartz, S.R.; Anne, S.; Adunka, O.F.; Bender, K.; Bold, K.M.; Brenner, M.J.; Hashmi, A.Z.; et al. Clinical Practice Guideline: Age-Related Hearing Loss. Otolaryngol.–Head Neck Surg. 2024, 170, S1–S54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wazen, J.J.; Ortega, C.; Nazarian, R.; Smith, J.; Thompson, J., Jr.; Lange, L. Expanding the indications for the bone anchored hearing system (BAHS) in patients with single sided deafness. Am. J. Otolaryngol. 2021, 42, 102864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schafer, E.C.; Grisel, J.J.; de Jong, A.; Ravelo, K.; Lam, A.; Burke, M.; Griffin, T.; Winter, M.; Schrader, D. Creating a framework for data sharing in cochlear implant research. Cochlear Implant. Int. 2016, 17, 283–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandavia, R.; Knight, A.; Carter, A.W.; Toal, C.; Mossialos, E.; Littlejohns, P.; Schilder, A.G. What are the requirements for developing a successful national registry of auditory implants? A qualitative study. BMJ Open 2018, 8, e021720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Italia. Decreto del Presidente del Consiglio dei Ministri 3 Marzo 2017. Gazzetta Ufficiale—Serie Generale n 109 12 Maggio 2017. 2017. Available online: https://www.gazzettaufficiale.it/eli/id/2017/05/12/17A03142/sg (accessed on 2 December 2025).

| ICD9-CM | Description | Implant |

|---|---|---|

| 20.95 | Implantation of electromagnetic hearing device | Non-cochlear |

| 20.97 | Implantation or replacement of cochlear prosthetic device, single channel | |

| 20.96 | Implantation or replacement of cochlear prosthetic device, not otherwise specified | Cochlear |

| 20.98 | Implantation or replacement of cochlear prosthetic device, multiple channels |

| Cochlear | Non-Cochlear | Overall | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 34 (26.7) | 49.3 (21.3) | 36.5 (26.5) |

| Females | 11,698 (51.2%) | 2362 (52.8%) | 14,060 (51.5%) |

| Males | 11,152 (48.8%) | 2114 (47.2%) | 13,266 (48.5%) |

| Age class < 1 | 522 (2.3%) | 9 (0.2%) | 531 (1.9%) |

| Age class 1–2 | 3148 (13.8%) | 58 (1.3%) | 3206 (11.7%) |

| Age class 3–17 | 5225 (22.9%) | 505 (11.3%) | 5730 (21%) |

| Age class 18–65 | 10,267 (44.9%) | 2745 (61.3%) | 13,012 (47.6%) |

| Age class 66–80 | 3412 (14.9%) | 1078 (24.1%) | 4490 (16.4%) |

| Age class > 80 | 276 (1.2%) | 81 (1.8%) | 357 (1.3%) |

| Total | 22,850 (100%) | 4476 (100%) | 27,326 (100%) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ciminello, E.; Cuda, D.; Forli, F.; Fetoni, A.R.; Berrettini, S.; Mattei, E.; Falcone, T.; Cuccu, A.; Ciccarelli, P.; Ceccarelli, S.; et al. Trends and Incidence of Hearing Implant Utilization in Italy: A Population-Based Study. Audiol. Res. 2025, 15, 175. https://doi.org/10.3390/audiolres15060175

Ciminello E, Cuda D, Forli F, Fetoni AR, Berrettini S, Mattei E, Falcone T, Cuccu A, Ciccarelli P, Ceccarelli S, et al. Trends and Incidence of Hearing Implant Utilization in Italy: A Population-Based Study. Audiology Research. 2025; 15(6):175. https://doi.org/10.3390/audiolres15060175

Chicago/Turabian StyleCiminello, Enrico, Domenico Cuda, Francesca Forli, Anna Rita Fetoni, Stefano Berrettini, Eugenio Mattei, Tiziana Falcone, Adriano Cuccu, Paola Ciccarelli, Stefania Ceccarelli, and et al. 2025. "Trends and Incidence of Hearing Implant Utilization in Italy: A Population-Based Study" Audiology Research 15, no. 6: 175. https://doi.org/10.3390/audiolres15060175

APA StyleCiminello, E., Cuda, D., Forli, F., Fetoni, A. R., Berrettini, S., Mattei, E., Falcone, T., Cuccu, A., Ciccarelli, P., Ceccarelli, S., & Torre, M. (2025). Trends and Incidence of Hearing Implant Utilization in Italy: A Population-Based Study. Audiology Research, 15(6), 175. https://doi.org/10.3390/audiolres15060175