Abstract

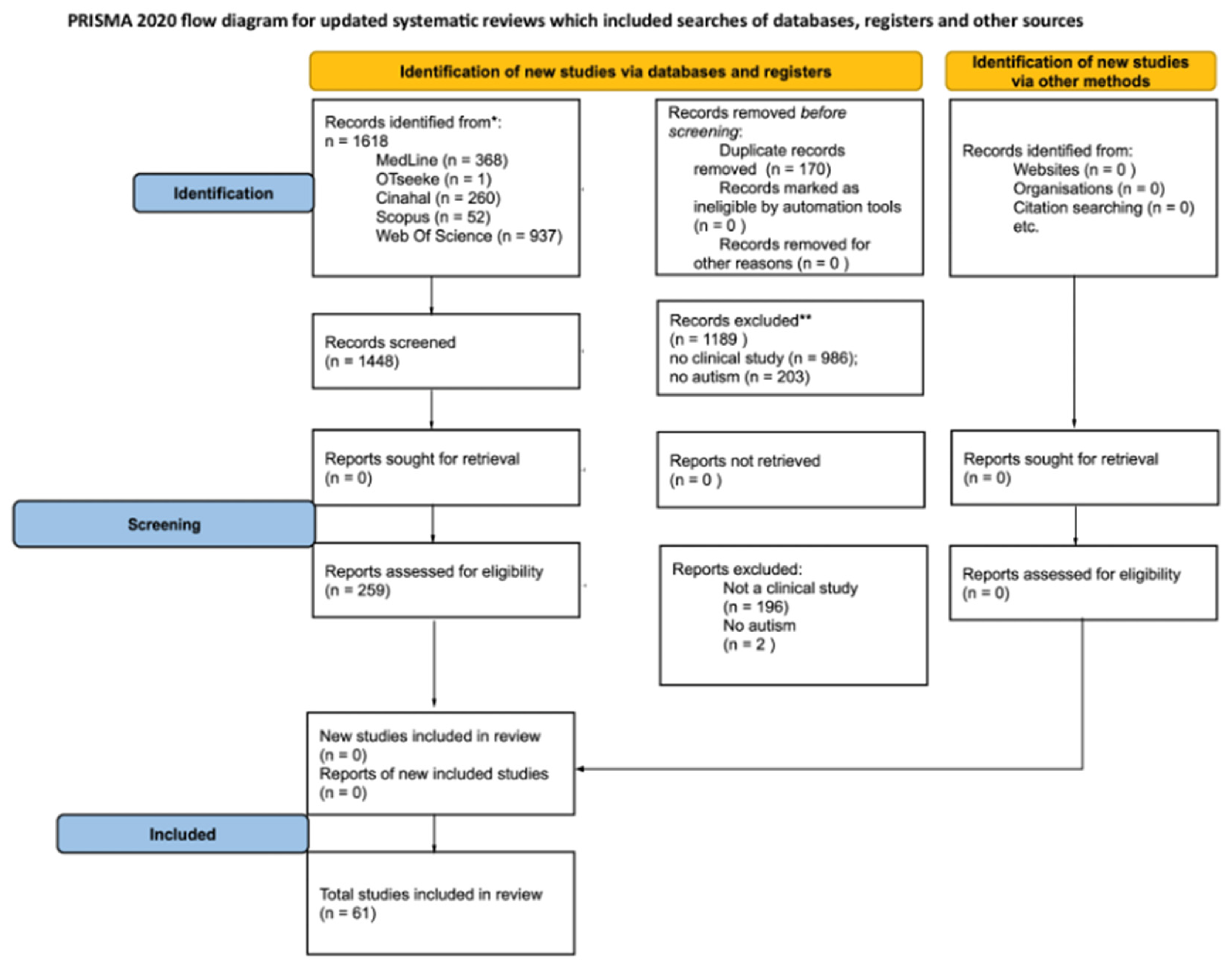

Background: This scoping review aims to synthesize existing evidence on non-pharmacological interventions for managing food selectivity in individuals with autism spectrum disorder (ASD). Specifically, it explores sensory, behavioral, and environmental factors influencing intervention outcomes and examines the role of occupational therapists (OTs) within multidisciplinary teams. Methods: A search was conducted across MEDLINE, EBSCO, Web of Science, OTseeker, and SCOPUS from August 2023 to October 2023. Only experimental studies published in English were included, focusing on behavioral treatments and/or occupational therapy interventions. Results: A total of 1618 studies were identified. After removing duplicates (170 records), 259 full-text articles were assessed for eligibility, resulting in 61 studies included for qualitative synthesis. Conclusions: The findings highlight a wide range of interventions, yet methodological inconsistencies and small sample sizes limit the strength of the evidence. While occupational therapists play an increasing role in feeding interventions, their specific impact remains underexplored. Future research should focus on larger, well-designed studies with standardized outcome measures to better define the effectiveness of interventions and the role of OTs within multidisciplinary teams.

1. Introduction

Autism spectrum disorder (ASD) is classified in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5) as a chronic neurodevelopmental disorder with a multifactorial etiology encompassing genetic, neurobiological, and environmental determinants [1]. It is characterized by persistent deficits in social communication and interaction across multiple contexts, along with restricted, repetitive patterns of behavior, interests, or activities. These core symptoms, including impaired reciprocal social interaction and highly stereotyped interests, significantly impact daily functioning. Symptoms typically emerge in early childhood, becoming apparent when social demands exceed developmental capacities, and their severity varies depending on context [2]. Recent studies highlight a rising global prevalence of ASD, with estimates suggesting that approximately 1 in 100 children worldwide receive a diagnosis [3].

Common comorbidities include cognitive impairments, hyperactivity, and difficulties in affective and sensory regulation. Sensory sensitivities—hypo- or hyper-sensitivity to stimuli—are particularly prevalent, often contributing to altered adaptive responses, including maladaptive eating behaviors [1,4]. For instance, hyper-sensitivity to taste, texture, or temperature may lead to the rejection of foods, while hypo-sensitivity may manifest as the ingestion of non-food items. Feeding difficulties affect up to 75% of children with ASD, with food selectivity, also known as selective eating disorder SED) [1,5] being the most common presentation [6]. This condition frequently overlaps with avoidant/restrictive food intake disorder (ARFID), a condition characterized by a restriction or avoidance of food intake that may lead to nutritional deficiencies and impair physical health [6]. Maladaptive eating behaviors, such as SED or anorexia nervosa [7,8], obesity, repeated ingestion of non-food products (PICA), restrictive eating avoidance disorder (AFRID), rumination and food neophobia [9], significantly compromise both physical health and psychosocial functioning. These disturbances disrupt family routines, elevate caregiver stress, and limit social participation, creating challenges that affect multiple domains of life. Among these, food selectivity stands out as one of the most pervasive and difficult symptoms to manage, with profound implications for nutritional status, quality of life, and overall family dynamics. While sensory sensitivities to taste and texture are recognized as contributing factors, they are not the sole determinants. Other influences, such as rigid adherence to routines or aversive experiences (e.g., choking or vomiting), may also play a role. Furthermore, diagnostic frameworks developed for the general population are often challenging to apply to individuals with severe cognitive impairments and high support needs, leading to inconsistencies in diagnosis and treatment approaches. While diagnostic criteria and therapeutic strategies for food selectivity in ASD remain inconsistent, the primary gap in the literature concerns the lack of clarity regarding the specific roles of healthcare professionals in managing these feeding difficulties. Despite the clinical significance of food selectivity in ASD, research remains fragmented, with significant gaps in understanding professional roles and intervention strategies. While existing studies have explored various interventions, there is a lack of clarity regarding the specific professional roles involved in managing food selectivity in children with ASD. The contribution of different specialists—such as occupational therapists, nutritionists, psychologists, and speech therapists—remains poorly defined, leading to inconsistencies in multidisciplinary approaches.

Unlike other aspects of ASD-related feeding difficulties, treatment standardization regarding type and duration is not a primary gap in the literature. However, the absence of a clear framework outlining the roles and responsibilities of healthcare professionals hinders the development of integrated, evidence-based interventions. A scoping review is therefore needed to map the existing evidence, clarify the involvement of different professionals, and provide guidance on how multidisciplinary teams can optimize treatment strategies for food selectivity in ASD. Pharmacological treatments, such as selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) and antipsychotics, have been explored in ASD-related feeding difficulties, but their efficacy remains uncertain. Studies suggest that while these medications may help with comorbid anxiety or obsessive–compulsive behaviors, they do not directly target food selectivity and often come with significant side effects, such as weight gain and metabolic disturbances. In contrast, behavioral and sensory-based interventions address the underlying mechanisms of food selectivity and have shown promising results in modifying maladaptive eating behaviors. Given these considerations, this review focuses on non-pharmacological interventions as a more targeted and sustainable approach to managing food selectivity in ASD [3]. These findings align with the growing recognition of the need for holistic, individualized approaches that address behavioral and contextual factors influencing feeding difficulties [10]. The majority of programs are based on behavioral, sensory, and nutritional approaches. Behavioral therapies, such as Applied Behavior Analysis (ABA), use positive reinforcement and escape extinction strategies to reduce food avoidance. Sensory interventions focus on gradual desensitization to tastes and textures, while nutritional approaches involve nutrition education and diet customization [11].

The involvement of occupational therapists in multidisciplinary teams is important, as their expertise in sensory processing and adaptive behaviors addresses factors that contribute to the development and persistence of pediatric feeding disorders. Occupational therapy interventions, such as modifying food textures and enhancing sensory experiences, can play a significant role in promoting more effective feeding behaviors and supporting long-term treatment success) [11].

This scoping review aims to address the following questions: (1) What are the non-pharmacological interventions for managing food selectivity in individuals with ASD? (2) How do sensory, behavioral, and environmental factors influence the outcomes of these interventions? (3) What is the role of occupational therapists in these programs? By answering these questions, this study seeks to provide evidence-based guidance for clinicians and caregivers, ultimately improving care for individuals with ASD.

2. Methods

The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR) statement was used for the manuscript reporting [12]. The protocol was registered in the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews [PROSPERO: CRD42023476083] and is publicly available.

2.1. Eligibility Criteria

Inclusion criteria: studies were selected based on the following criteria: (i) Randomized Controlled Trials, Pilot Randomized Controlled Trials, Pilot Studies, Quasi-experimental Studies, and Case Series; (ii) studies involving participants with a confirmed diagnosis of ASD, with no age or gender differences considered; (iii) studies that report non-pharmacological treatments (psychological, rehabilitative, behavioral, sensory, etc.). Exclusion criteria: data published as abstracts or conference proceedings, observational studies, letters to editors, reviews, meta-analyses, or animal model research.

2.2. Information Sources

To identify potentially relevant documents, the following bibliographic databases were searched from 2023 to October 2024: MEDLINE, EBSCO, Web of Science, OTseeker, and SCOPUS. The search strategies were drafted by an experienced librarian (G.G) and further refined through team discussion. The final search strategy for MEDLINE was: ((autism or ASD or autism spectrum disorder or Asperger’s or Asperger syndrome or autistic disorder or Aspergers) AND (food selectivity or eating disorders or anorexia or bulimia or disordered eating or binge eating disorder) AND (treatment or intervention or therapy or management or rehabilitation)), and was subsequently adapted for the other databases. The search was performed to find English-language articles.

2.3. Selection of Sources of Evidence

Two independent reviewers (R.S., S.C.) extensively searched MEDLINE, EBSCO, Web of Science, OTseeker, and SCOPUS to identify eligible studies. Each information source was examined from inception to October 2024. References of included papers were reviewed to ensure that no relevant studies were missing through the electronic database searches. We resolved disagreements on study selection and data extraction by consensus and discussion with other reviewers if needed.

2.4. Data Charting

A data-charting form was jointly developed by two reviewers to determine which variables to extract. Rayyan QCRI online software was used to remove duplicates and for the study selection [13]. The two reviewers independently charted the data (R.S.; S.C.), discussed the results, and continuously updated the data-charting form in an iterative process. A third reviewer (A.B.) solved disagreements.

Data Items

The following data from included studies were extracted by two independent reviewers (R.S., S.C.) using a planned standardized spreadsheet: (i) study design; (ii) aim of the study; (iii) sample size; (iv) mean age (SD); (v) intervention; (vi) intervention duration; (vii) results; (viii) health professionals.

2.5. Analysis

Given the heterogeneity of the study designs and outcome measures in the included articles, data synthesis was performed in a structured manner. First, we grouped the studies based on the clinical focus of each reported outcome. Specifically, we categorized them into the following domains: (1) type of intervention and (2) health professionals involved. The data were pooled and analyzed within the most appropriate category for studies reporting multiple outcomes across different domains.

3. Results

As reported in Figure 1, the total number of items retrieved from databases was 1618. Once duplicates were removed (170 searches), the full text of 259 articles was analyzed and 61 articles were included for qualitative synthesis.

Figure 1.

PRISMA Flowchart. * Consider, if feasible to do so, reporting the number of records identified from each database or register searched (rather than the total number across all databases/registers). ** If automation tools were used, indicate how many records were excluded by a human and how many were excluded by automation tools.

As reported in Table 1, sixty-one studies were published between 2001 and 2023. Of these, there were 14 case series [14,15,16,17,18,19]; 12 clinical trials [20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31]; 7 pilot studies [32,33,34,35,36,37,38]; 10 between experimental and quasi-experimental studies [39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48]; 2 retrospective studies [49,50]; 6 prospective studies [51,52,53,54,55,56]; 3 preliminary studies [57,58,59]; 4 qualitative studies [60,61,62,63]; a quantitative follow-up study [64]; and 10 studies between RCT and pilot RCT [5,65,66,67,68,69,70,71,72,73]. All studies analyzed the effects of different non-pharmacological therapeutic approaches aimed at improving feeding difficulties in individuals with ASD. As reported in Table 2, the studies focused on various interventions, including behavioral, sensory, and nutritional approaches. In particular, five studies examined the effects of the “Bringing Adolescent Learners with Autism Nutrition and Culinary Education” (BALANCE) intervention; four evaluated the effectiveness of Applied Behavior Analysis (ABA); four others studied sequential and simultaneous food presentation strategies; three focused on the Managing Eating Aversions and Limited Variety (MEAL) Plan; three examined video modeling techniques; three assessed behavioral interventions based on Differential Reinforcement of Alternative Behavior (DRA) and Escape Extinction (EE); two analyzed the dietary intervention “Easing Anxiety Together with Understanding and Perseverance” (EAT-UP); and two evaluated the Parent Training for Feeding (PT-F) program. Tables were used to report the following main data: author (year), study design, target, sample size, average age of the sample, intervention, duration of intervention, outcome measures, control, professional figures, follow-up, and results. The content and methodology of the studies were qualitatively analyzed, summarizing the main results based on intervention on eating disorders.

Table 1.

Data extraction table.

Table 2.

Intervention type.

3.1. Nutritional Intervention “Bringing Adolescent Learners with Autism Nutrition and Culinary Education” (BALANCE)

The BALANCE intervention program incorporates principles of Social and Cognitive Theory (SCT) and techniques for treating food selectivity and feeding difficulties in ASD. This specific intervention was analyzed in five different studies [35,54,60,61,62] and the feasibility of its application in a virtual environment, through the optimization of the theoretical framework, was evaluated in terms of acceptability, benefits, and undesirable consequences. In general, good results were found with regard to: feasibility, attendance rate, completion of tasks, treatment fidelity, and lack of technical difficulties, with improvements in dietary intake levels and self-efficacy. Findings indicate good feasibility, high attendance rates, successful task completion, and treatment fidelity. Positive effects were observed in dietary intake and self-efficacy. However, limitations include small sample sizes and the need for individualized adaptations.

3.2. Behavioral Analytical Interventions (ABA)

The ABA method is based mainly on four key principles: reinforcement, extinction, stimulus control, and generalization. Studies using ABA (n = 4) consistently reported increased food acceptance and reduced problem behaviors related to feeding. Two of these studies involved an occupational therapist, whose role included supporting sensory adaptations and structuring mealtime environments. However, the effectiveness of ABA may depend on factors such as intervention intensity, individual responsiveness, and co-occurring sensory sensitivities.

3.3. Simultaneous and Sequential Presentation Mode of Food

Four studies examined the impact of presenting preferred and non-preferred foods either simultaneously or sequentially. Results were mixed: while sequential presentation, combined with escape extinction, showed promising results in increasing acceptance of non-preferred foods, simultaneous presentation alone was generally less effective. Some studies suggest that combining these methods with reinforcement strategies may enhance their efficacy.

3.4. Managing Eating Aversions and Limited Variety (MEAL) Plan

The MEAL Plan is a structured intervention that actively involves parents in addressing food selectivity in children with ASD. Three studies evaluated its effectiveness, reporting improvements in food acceptance and reductions in parental stress. However, successful implementation relies on caregivers’ adherence and consistency, which may present challenges in real-world settings.

3.5. Videomodeling

Video modeling is an observational learning technique used to teach appropriate behaviors. Three studies explored its application in home settings, demonstrating positive effects on food-related autonomy and behavior regulation. One study specifically highlighted the role of occupational therapists in structuring and implementing video modeling sessions. However, more research is needed to determine the long-term sustainability of these outcomes.

3.6. Behavioral Intervention Based on Differential Reinforcement of Behavior Alternative (DRA) and Leak Quenching (EE)

DRA involves reinforcing appropriate eating behaviors, while EE prevents avoidance behaviors by ensuring continued exposure to non-preferred foods. Three studies examined these techniques, showing increased food variety and consumption. However, the effectiveness of these interventions may be influenced by factors such as individual tolerance levels and parental involvement. In one study, the occupational therapist played a critical role in assessing feeding-related skills and selecting target foods in collaboration with parents [26,57].

3.7. Food Intervention Easing Anxiety Together with Understanding and Perseverance (EAT-UP)

The EAT-UP model is a family-centered intervention designed to reduce anxiety and increase food acceptance in children with ASD. Two studies (one follow-up and one preliminary) reported improvements in food acceptance and meal-related behaviors. High procedural fidelity among both clinicians and parents suggests strong feasibility. However, further research is needed to compare EAT-UP with other family-based interventions [59,64].

3.8. Parent Training for Feeding (PT-F) Program

The PT-F program trains parents in behavioral strategies to manage mealtime challenges. Two studies found it effective in reducing disruptive behaviors and improving parental confidence. Overall satisfaction with the program was high, but the need for structured follow-up and ongoing support was emphasized [63,65].

From the analysis of the results, several trends emerge: (i) Behavioral interventions (e.g., ABA, DRA/EE, PT-F) show strong effectiveness in increasing food acceptance and reducing mealtime challenges. However, their success depends on consistent implementation and individual responsiveness. (ii) Sensory-based approaches (BALANCE, EAT-UP) demonstrate potential benefits, but further research is needed to directly compare them with behavioral interventions. (iii) Parental involvement is a critical factor in successful outcomes. Programs like MEAL Plan and PT-F highlight the importance of training caregivers, though challenges related to adherence remain. (iv) The role of occupational therapists varies across studies. While some studies integrate OTs into intervention teams, their specific contributions (e.g., sensory adaptations and environmental structuring) are not always clearly defined. Future research should explore their impact in greater detail. (v) Long-term sustainability of intervention outcomes is unclear. Most studies assess short-term effects, and few examine maintenance beyond the intervention period. Longitudinal studies are needed to determine lasting benefits.

This review underscores the importance of integrating multiple approaches to address food selectivity in ASD. Future research should focus on optimizing intervention strategies, defining the role of occupational therapists, and evaluating long-term effectiveness.

4. Discussion

This scoping review aimed to address the following questions: (1) What are the non-pharmacological interventions for managing food selectivity in individuals with ASD? (2) How do sensory, behavioral, and environmental factors influence the outcomes of these interventions? (3) What is the role of occupational therapists in these programs? This study aims to offer evidence-based guidance to clinicians and caregivers to enhance care for individuals with ASD. Sixty-one studies were examined, and a critical analysis revealed significant methodological limitations across most of them. Specifically, only 13 studies included a control group [5,16,21,23,30,53,65,66,68,69,70,72,73]; limiting the ability to establish causal relationships between interventions and outcomes. Furthermore, only three studies featured a homogeneous sample in terms of age [22,26,55]; while most studies had small sample sizes (<30 participants), with the exception of eight studies [36,42,49,65,66,70,72,73]. Follow-up assessments were conducted in only 26 studies, indicating that long-term effectiveness remains largely unexplored [15,16,17,18,21,25,26,29,30,32,39,41,47,48,49,51,52,55,56,59,66,67,70,71,72,73]. Several studies were published between 2022 and 2023. Replication studies and larger-scale trials are needed to validate these findings [25,35,43,44,54,58,60,62,67,71,72,73]. Despite these limitations, the analysis of 61 articles highlights the growing involvement of occupational therapists in ASD feeding interventions over time [5,15,20,21,32,33,34,45,49,53,57,70]. Among the included studies, 49 articles focused on sensory and behavioral interventions, 7 on nutritional interventions, 3 on sensory interventions, 1 on muscular reinforcement, and 1 on rehabilitation. However, the lack of standardization in intervention protocols, outcome measures, and participant characteristics makes direct comparisons challenging. Among the studies that concern behavioral interventions, those both statistically and clinically significant are: the study by Marshall et al. (2015) [70], which compared operant conditioning (OC) and systematic desensitization (SysD) in improving food variety and reducing mealtime problem behaviors; Sharp et al. (2014) [69], which evaluated the feasibility and effectiveness of the MEAL Plan study, highlighting its structured approach to managing food selectivity; Laud et al. (2009) [49], which assessed an interdisciplinary feeding program using behavioral treatment strategies; the study by Panerai et al. (2018) [25], which examined a multidisciplinary, intensive behavioral intervention for children with ASD and intellectual disability (ID); the study by Miyajima et al. (2017) [53], which developed and tested a new parenting intervention program to improve selective eating behaviors in children with ASD; and the study by Thorsteinsdottir et al. (2022) [71], investigated the effects of the “Taste Education” program on mealtime behaviors in children with ASD. Among the most studied interventions, the BALANCE program—an 8-week nutritional intervention—has been analyzed in five studies. One study [62] incorporated virtual focus groups, adding an interactive component to the intervention. However, the age range (12–21 years) and the use of varying outcome measures (FFQ, PAS, ABI-SF) limit the generalizability of the findings.

ABA-based interventions lack consistency in the number of weekly sessions, total duration, and assessment methods. Different measurement tools (CEBI, SSIS) were applied across studies, further complicating comparisons. Additionally, participant age ranges varied significantly, reducing the ability to draw generalized conclusions.

In the case of sequential and simultaneous food presentation strategies, only three studies [27,44,63] evaluated their effectiveness, with intervention frequency ranging from two to four sessions per week. These studies lacked standardized outcome measures and included heterogeneous age groups, making it difficult to determine the efficacy of these strategies.

Similarly, MEAL Plan interventions showed heterogeneity in session duration, total treatment length, and participant characteristics. Three studies applied the Brief Autism Mealtime Behavior Inventory (BAMBI), but additional outcome measures varied across studies, limiting comparability.

The video modeling technique was assessed in three studies, but none utilized objective outcome measures. Sample sizes were extremely small (n = 3 per study), with significant age variability. Only two studies [15,31] included children of similar ages (3–4 years), making it difficult to determine broader applicability. For DRA and Escape Extinction (EE) interventions, the number and duration of sessions varied significantly among the three studies that examined them. Only one study [41] employed an objective evaluation measure (the Brief Parent Satisfaction Questionnaire), while the other two lacked standardized assessments. Participant age ranges were inconsistent across studies, preventing clear conclusions about the effectiveness of these techniques.

The EAT-UP model, analyzed in two studies, had a treatment duration of 5–6 months. Effectiveness was assessed using BAMBI and FFQ in both studies, with one study [59] additionally employing the Behavioral Pediatrics Feeding Assessment Scale (BPFAS). However, age heterogeneity across studies limits generalizability.

Finally, the Parent Training for Feeding (PT-F) program lacks sufficient data to determine the optimal age group, session frequency, and duration of effectiveness. The two studies that examined this intervention used multiple evaluation tools (BAMBI, PSQ, Treatment Fidelity Checklist, ABC, PSI-Short Form), making cross-study comparisons difficult.

This review highlights key clinical implications. Clinicians should implement structured behavioral interventions, such as ABA-based programs, with standardized protocols and assessments. Moreover, sensory-based interventions like BALANCE and EAT-UP should be further explored in larger studies to confirm their efficacy. A key recommendation for clinicians is to actively involve caregivers in intervention plans, as programs like MEAL and PT-F show that parental participation greatly enhances treatment adherence and success. Lastly, clinicians should advocate for long-term follow-up assessments to better understand the sustainability of intervention effects over time.

The findings of this review have important implications for clinical practice:

(i) Behavioral interventions, particularly ABA-based approaches, show promise but require greater standardization in treatment protocols, session duration, and outcome assessments. (ii) Sensory-based interventions, such as BALANCE and EAT-UP, offer potential benefits, but their effectiveness needs to be validated through larger, well-controlled studies. (iii) Parental involvement plays a crucial role in intervention success. Programs like MEAL and PT-F highlight the importance of training caregivers, yet adherence and implementation fidelity remain challenges. (iv) The role of occupational therapists in feeding interventions is increasing, but future research should focus on quantifying their specific contributions to treatment outcomes. (v) There is a lack of long-term follow-up studies, making it difficult to assess the sustainability of intervention effects over time.

The role of occupational therapists in feeding interventions is increasingly recognized, but their specific contributions need further clarification. Occupational therapists apply a holistic, occupation-based approach that focuses on feeding as an essential daily activity within various life contexts. Their interventions include sensory integration techniques, adaptive strategies for mealtime participation, and caregiver training to enhance feeding routines. Several studies [5,15,20,21,32,33,34,45,49,53,57,70] highlight their involvement in feeding programs, demonstrating their role in improving sensory processing, motor coordination, and behavioral adaptations during mealtimes. Future research should aim to quantify the impact of occupational therapy interventions within multidisciplinary teams, ensuring their systematic integration into feeding programs for individuals with ASD. To address the variability in methodologies across studies, future research should prioritize the standardization of intervention protocols and outcome measures. Establishing uniform assessment criteria, such as using validated tools like BAMBI and FFQ across studies, would facilitate comparability and improve the reliability of findings. Furthermore, defining optimal session duration, frequency, and intervention length for ABA-based and sensory interventions would enhance the applicability of results in clinical practice. Standardized methodologies would also support the development of meta-analyses, enabling a more comprehensive understanding of effective strategies for managing food selectivity in ASD.

Future research should prioritize larger, well-designed RCTs to establish causal relationships between interventions and outcomes. Standardizing outcome measures will improve cross-study comparability and support meta-analyses. Additionally, long-term follow-ups are needed to assess intervention sustainability. Finally, further research is needed to clearly define the specific role of occupational therapists within interdisciplinary feeding programs, ensuring their contributions are well understood and effectively integrated into treatment approaches. This review highlights the need for more rigorous research methodologies to strengthen the evidence supporting non-pharmacological interventions for food selectivity in ASD. Addressing these gaps will enhance the practical application of interventions and improve outcomes for individuals with ASD and their families.

5. Conclusions

This review highlights the variety of non-pharmacological interventions for food selectivity in ASD, though their effectiveness is limited by methodological inconsistencies. Stronger evidence is needed through larger, well-designed RCTs with standardized outcome measures and longer follow-up periods. A key finding is the growing role of occupational therapists (OTs) in feeding interventions. OTs address sensory sensitivities and behavioral challenges, yet their specific impact remains underexplored. Future research should clarify their role and effectiveness within interdisciplinary teams. Clinically, integrating behavioral, sensory, and nutritional strategies appears most effective. Standardized protocols are needed to improve implementation and outcomes. Advancing research in these areas will provide clearer guidance for practitioners and caregivers.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th ed.; American Psychiatric Association Publishing: Washington, DC, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kodak, T.; Bergmann, S. Autism Spectrum Disorder. Pediatr. Clin. N. Am. 2020, 67, 525–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choi, H.; Kim, J.H.; Yang, H.S.; Kim, J.Y.; Cortese, S.; Smith, L.; Koyanagi, A.; Dragioti, E.; Radua, J.; Fusar-Poli, P.; et al. Pharmacological and non-pharmacological interventions for irritability in autism spectrum disorder: A systematic review and meta-analysis with the GRADE assessment. Mol. Autism 2024, 15, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esposito, M.; Mirizzi, P.; Fadda, R.; Pirollo, C.; Ricciardi, O.; Mazza, M.; Valenti, M. Food Selectivity in Children with Autism: Guidelines for Assessment and Clinical Interventions. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 5092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peterson, K.M.; Piazza, C.C.; Volkert, V.M. A comparison of a modified sequential oral sensory approach to an applied behavior-analytic approach in the treatment of food selectivity in children with autism spectrum disorder. J. Appl. Behav. Anal. 2016, 49, 485–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kozak, A.; Czepczor-Bernat, K.; Modrzejewska, J.; Modrzejewska, A.; Matusik, E.; Matusik, P. Avoidant/Restrictive Food Disorder (ARFID), Food Neophobia, Other Eating-Related Behaviours and Feeding Practices among Children with Autism Spectrum Disorder and in Non-Clinical Sample: A Preliminary Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 5822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Postorino, V.; Sanges, V.; Giovagnoli, G.; Fatta, L.M.; De Peppo, L.; Armando, M.; Vicari, S.; Mazzone, L. Clinical differences in children with autism spectrum disorder with and without food selectivity. Appetite 2015, 92, 126–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brown, C.M.; Stokes, M.A. Intersection of Eating Disorders and the Female Profile of Autism. Child. Adolesc. Psychiatr. Clin. N. Am. 2020, 29, 409–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petitpierre, G.; Luisier, A.-C.; Bensafi, M. Eating behavior in autism: Senses as a window towards food acceptance. Curr. Opin. Food Sci. 2021, 41, 210–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertelli, M.O.; Paletti, F.; Merli, M.P.; Hassiotis, A.; Bianco, A.; Lassi, S. Eating and feeding disorders in adults with intellectual developmental disorder with and without autism spectrum disorder. J. Intellect. Disabil. Res. 2025, 69, 153–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharp, W.G.; Volkert, V.M.; Scahill, L.; McCracken, C.E.; McElhanon, B. A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Intensive Multidisciplinary Intervention for Pediatric Feeding Disorders: How Standard Is the Standard of Care? J. Pediatr. 2017, 181, 116–124.e4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ouzzani, M.; Hammady, H.; Fedorowicz, Z.; Elmagarmid, A. Rayyan—A web and mobile app for systematic reviews. Syst. Rev. 2016, 5, 210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crowley, J.G.; Peterson, K.M.; Fisher, W.W.; Piazza, C.C. Treating food selectivity as resistance to change in children with autism spectrum disorder. J. Appl. Behav. Anal. 2020, 53, 2002–2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hillman, H. Home-Based Video Modeling on Food Selectivity of Children with an Autism Spectrum Disorder. Phys. Occup. Ther. Pediatr. 2019, 39, 629–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taylor, T.; Blampied, N.; Roglić, N. Controlled case series demonstrates how parents can be trained to treat paediatric feeding disorders at home. Acta Paediatr. 2021, 110, 149–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koegel, R.L.; Bharoocha, A.A.; Ribnick, C.B.; Ribnick, R.C.; Bucio, M.O.; Fredeen, R.M.; Koegel, L.K. Using Individualized Reinforcers and Hierarchical Exposure to Increase Food Flexibility in Children with Autism Spectrum Disorders. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2012, 42, 1574–1581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seiverling, L.; Williams, K.; Sturmey, P.; Hart, S. Effects of Behavioral Skills Training on Parental Treatment of Children’s Food Selectivity. J. Appl. Behav. Anal. 2012, 45, 197–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Connor, E.; Cividini-Motta, C.; MacNaul, H. Treatment of food selectivity: An evaluation of video modeling of contingencies. Behav. Interv. 2020, 35, 57–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, T.; Kozlowski, A.M.; Girolami, P.A. Comparing behavioral treatment of feeding difficulties and tube dependence in children with cerebral palsy and autism spectrum disorder. NeuroRehabilitation 2017, 41, 395–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seiverling, L.; Anderson, K.; Rogan, C.; Alaimo, C.; Argott, P.; Panora, J. A Comparison of a Behavioral Feeding Intervention with and Without Pre-meal Sensory Integration Therapy. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2018, 48, 3344–3353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, V.R.; Ledford, J.R.; Lord, A.K.; Harbin, E.R. Response shaping to improve food acceptance for children with autism: Effects of small and large food sets. Res. Dev. Disabil. 2020, 98, 103574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levin, L.; Carr, E.G. Food Selectivity and Problem Behavior in Children with Developmental Disabilities. Behav. Modif. 2001, 25, 443–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silbaugh, B.C.; Swinnea, S. Failure to Replicate the Effects of the High-Probability Instructional Sequence on Feeding in Children with Autism and Food Selectivity. Behav. Modif. 2019, 43, 734–762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panerai, S.; Suraniti, G.S.; Catania, V.; Carmeci, R.; Elia, M.; Ferri, R. Improvements in mealtime behaviors of children with special needs following a day-center-based behavioral intervention for feeding problems. Riv. Psichiatr. 2018, 53, 299–308. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Russo, S.R.; Croner, J.; Smith, S.; Chirinos, M.; Weiss, M.J. A further refinement of procedures addressing food selectivity. Behav. Interv. 2019, 34, 495–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Penrod, B.; VanDalen, K.H. An evaluation of emerging preference for non-preferred foods targeted in the treatment of food selectivity. Behav. Interv. 2010, 25, 239–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burton, C.; Allan, E.; Eckhardt, S.; Le Grange, D.; Ehrenreich-May, J.; Singh, M.; Dimitropoulos, G. Case Presentations Combining Family-Based Treatment with the Unified Protocols for Transdiagnostic Treatment of Emotional Disorders in Children and Adolescents for Comorbid Avoidant Restrictive Food Intake Disorder and Autism Spectrum Disorder. J. Can. Acad. Child. Adolesc. Psychiatry 2021, 30, 280–291. [Google Scholar]

- Gale, C.M.; Eikeseth, S.; Rudrud, E. Functional Assessment and Behavioural Intervention for Eating Difficulties in Children with Autism: A study Conducted in the Natural Environment Using Parents and ABA Tutors as Therapists. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2011, 41, 1383–1396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Flanagan, J.; Penrod, B.; Silbaugh, B.C. Further evaluation of contingency modeling to increase consumption of nutritive foods in children with autism and food selectivity. Behav. Interv. 2021, 36, 892–909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, R.J.; Wilder, D.A.; Kelley, M.E.; Ryan, V. Evaluation of Instructions and Video Modeling to Train Parents to Implement a Structured Meal Procedure for Food Selectivity Among Children with Autism. Behav. Anal. Pr. 2020, 13, 674–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuschner, E.S.; Morton, H.E.; Maddox, B.B.; de Marchena, A.; Anthony, L.G.; Reaven, J. The BUFFET Program: Development of a Cognitive Behavioral Treatment for Selective Eating in Youth with Autism Spectrum Disorder. Clin. Child. Fam. Psychol. Rev. 2017, 20, 403–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harpster, K.; Burkett, K.; Walton, K.; Case-Smith, J. Evaluating the Effects of the Engagement–Communication–Exploration (ECE) Snack Time Intervention for Preschool Children with Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD). Am. J. Occup. Ther. 2015, 69, 6911515227p1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suarez, M.A.; Bush, E. Pilot Study of the Just Right Challenge Feeding Protocol for Treatment of Food Selectivity in Children. Open J. Occup. Ther. 2020, 8, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buro, A.W.; Gray, H.L.; Kirby, R.S.; Marshall, J.; Strange, M.; Hasan, S.; Holloway, J. Pilot Study of a Virtual Nutrition Intervention for Adolescents and Young Adults with Autism Spectrum Disorder. J. Nutr. Educ. Behav. 2022, 54, 853–862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manzanarez, B.; Garcia, S.; Iverson, E.; Lipton-Inga, M.R.; Blaine, K. Lessons in Adapting a Family-Based Nutrition Program for Children with Autism. J. Nutr. Educ. Behav. 2021, 53, 1038–1047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matheson, B.E.; Drahota, A.; Boutelle, K.N. A Pilot Study Investigating the Feasibility and Acceptability of a Parent-Only Behavioral Weight-Loss Treatment for Children with Autism Spectrum Disorder. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2019, 49, 4488–4497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johnson, C.R.; Foldes, E.; DeMand, A.; Brooks, M.M. Behavioral Parent Training to Address Feeding Problems in Children with Autism Spectrum Disorder: A Pilot Trial. J. Dev. Phys. Disabil. 2015, 27, 591–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, T. Side Deposit with Regular Texture Food for Clinical Cases In-Home. J. Pediatr. Psychol. 2020, 45, 399–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cihon, J.; Weiss, M.J.; Ferguson, J.L.; Leaf, J.B.; Zane, T.; Ross, R. Observational Effects on the Food Preferences of Children with Autism Spectrum Disorder. Focus. Autism Other Dev. Disabl. 2021, 36, 25–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Najdowski, A.C.; Wallace, M.D.; Reagon, K.; Penrod, B.; Higbee, T.S.; Tarbox, J. Utilizing a home-based parent training approach in the treatment of food selectivity. Behav. Interv. 2010, 25, 89–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, L.M.Y.; Law, Q.P.S.; Fong, S.S.M. Using Physical Food Transformation to Enhance the Sensory Approval of Children with Autism Spectrum Disorders for Consuming Fruits and Vegetables. J. Altern. Complement. Med. 2020, 26, 1074–1079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, L.; Hu, X.; Zhai, Y.; Zhang, G.; Wang, X. Teaching self-control to reduce overt food stealing by children with autism and developmental disorders. Behav. Interv. 2023, 38, 725–738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, M.; Slaton, J.; MacDonald, J.; Parry-Cruwys, D. Comparing Simultaneous and Sequential Food Presentation to Increase Consumption of Novel Target Foods. Behav. Anal. Pract. 2023, 16, 1124–1137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, H. The Effect of Oral Motor Therapy on Feeding Difficulties and Eating Behaviors in Younger ASD Children. J. Res. Med. Dent. Sci. 2021, 9, 334–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.Y.; Chung, K.-M.; Jung, S. Effects of repeated food exposure on increasing vegetable consumption in preschool children with autism spectrum disorder. Res. Autism Spectr. Disord. 2018, 47, 26–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- VanDalen, K.H.; Penrod, B. A comparison of simultaneous versus sequential presentation of novel foods in the treatment of food selectivity. Behav. Interv. 2010, 25, 191–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Penrod, B.; Wallace, M.D.; Reagon, K.; Betz, A.; Higbee, T.S. A component analysis of a parent-conducted multi-component treatment for food selectivity. Behav. Interv. 2010, 25, 207–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laud, R.B.; Girolami, P.A.; Boscoe, J.H.; Gulotta, C.S. Treatment Outcomes for Severe Feeding Problems in Children With Autism Spectrum Disorder. Behav. Modif. 2009, 33, 520–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seiverling, L.; Hendy, H.M.; Yusupova, S.; Kaczor, A.; Panora, J.; Rodriguez, J. Improvements in Children’s Feeding Behavior after Intensive Interdisciplinary Behavioral Treatment: Comparisons by Developmental and Medical Status. Behav. Modif. 2020, 44, 891–908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, S.B.; Penrod, B.; Fernand, J.K.; Whelan, C.M.; Griffith, K.; Medved, S. The Effects of Modeling Contingencies in the Treatment of Food Selectivity in Children with Autism. Behav. Modif. 2015, 39, 771–784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paul, C.; Williams, K.E.; Riegel, K.; Gibbons, B. Combining repeated taste exposure and escape prevention: An intervention for the treatment of extreme food selectivity. Appetite 2007, 49, 708–711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miyajima, A.; Tateyama, K.; Fuji, S.; Nakaoka, K.; Hirao, K.; Higaki, K. Development of an Intervention Programme for Selective Eating in Children with Autism Spectrum Disorder. Hong Kong J. Occup. Ther. 2017, 30, 22–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buro, A.W.; Gray, H.L.; Kirby, R.S.; Marshall, J.; Strange, M.; Pang, T.; Hasan, S.; Holloway, J. Feasibility of a virtual nutrition intervention for adolescents with autism spectrum disorder. Autism 2022, 26, 1436–1450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Levin, D.S.; Volkert, V.M.; Piazza, C.C. A Multi-Component Treatment to Reduce Packing in Children with Feeding and Autism Spectrum Disorders. Behav. Modif. 2014, 38, 940–963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Penrod, B.; Gardella, L.; Fernand, J. An Evaluation of a Progressive High-Probability Instructional Sequence Combined with Low-Probability Demand Fading in the Treatment of Food Selectivity. J. Appl. Behav. Anal. 2012, 45, 527–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ulloa, G.; Borrero, C.S.W.; Borrero, J.C. Behavioral Interventions for Pediatric Food Refusal Maintain Effectiveness Despite Integrity Degradation: A Preliminary Demonstration. Behav. Modif. 2020, 44, 746–772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ivy, J.W.; Williams, K.; Davison, L.; Bacon, B.; Carriles, F.E. Increasing Vegetable Consumption in Students with Autism Spectrum Disorder Using Pre-Meal Presentation: A Preliminary Analysis. J. Behav. Educ. 2022, 31, 561–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cosbey, J.; Muldoon, D. EAT-UPTM Family-Centered Feeding Intervention to Promote Food Acceptance and Decrease Challenging Behaviors: A Single-Case Experimental Design Replicated Across Three Families of Children with Autism Spectrum Disorder. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2017, 47, 564–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buro, A.; Gray, H. O01 Optimizing a Theoretical Framework for Virtual Nutrition Education Programs for Adolescents with Autism Spectrum Disorder. J. Nutr. Educ. Behav. 2022, 54, S1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buro, A.; Rolle, L.; Gray, H. O13 Acceptability, Perceived Benefits, and Unintended Consequences of a Virtual Nutrition Intervention for Adolescents with Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD). J. Nutr. Educ. Behav. 2021, 53, S6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buro, A.W.; Gray, H.L.; Kirby, R.S.; Marshall, J.; Rolle, L.; Holloway, J. Parent and Adolescent Attitudes Toward a Virtual Nutrition Intervention for Adolescents with Autism Spectrum Disorder. Adv. Neurodev. Disord. 2023, 7, 94–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weber, J.; Gutierrez, A., Jr. A Treatment Package without Escape Extinction to Address Food Selectivity. J. Vis. Exp. 2015, e52898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muldoon, D.; Cosbey, J. A Family-Centered Feeding Intervention to Promote Food Acceptance and Decrease Challenging Behaviors in Children With ASD: Report of Follow-Up Data on a Train-the-Trainer Model Using EAT-UP. Am. J. Speech Lang. Pathol. 2018, 27, 278–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johnson, C.R.; Brown, K.; Hyman, S.L.; Brooks, M.M.; Aponte, C.; Levato, L.; Schmidt, B.; Evans, V.; Huo, Z.; Bendixen, R. Parent Training for Feeding Problems in Children with Autism Spectrum Disorder: Initial Randomized Trial. J. Pediatr. Psychol. 2019, 44, 164–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharp, W.G.; Burrell, T.L.; Berry, R.C.; Stubbs, K.H.; McCracken, C.E.; Gillespie, S.E.; Scahill, L. The Autism Managing Eating Aversions and Limited Variety Plan vs Parent Education: A Randomized Clinical Trial. J. Pediatr. 2019, 211, 185–192.e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burrell, T.L.; Scahill, L.; Nuhu, N.; Gillespie, S.; Sharp, W. Exploration of Treatment Response in Parent Training for Children with Autism Spectrum Disorder and Moderate Food Selectivity. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2023, 53, 229–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peterson, K.M.; Piazza, C.C.; Ibañez, V.F.; Fisher, W.W. Randomized controlled trial of an applied behavior analytic intervention for food selectivity in children with autism spectrum disorder. J. Appl. Behav. Anal. 2019, 52, 895–917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharp, W.G.; Burrell, T.L.; Jaquess, D.L. The Autism MEAL Plan: A parent-training curriculum to manage eating aversions and low intake among children with autism. Autism 2014, 18, 712–722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marshall, J.; Hill, R.J.; Ware, R.S.; Ziviani, J.; Dodrill, P. Multidisciplinary Intervention for Childhood Feeding Difficulties. J. Pediatr. Gastroenterol. Nutr. 2015, 60, 680–687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thorsteinsdottir, S.; Njardvik, U.; Bjarnason, R.; Olafsdottir, A.S. Changes in Eating Behaviors Following Taste Education Intervention: Focusing on Children with and without Neurodevelopmental Disorders and Their Families: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Nutrients 2022, 14, 4000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kral, T.V.E.; O’Malley, L.; Johnson, K.; Benvenuti, T.; Chittams, J.; Quinn, R.J.; Thomas, J.G.; Pinto-Martin, J.A.; Levy, S.E.; Kuschner, E.S. Effects of a mobile health nutrition intervention on dietary intake in children who have autism spectrum disorder. Front. Pediatr. 2023, 11, 1100436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gray, H.L.; Pang, T.; Agazzi, H.; Shaffer-Hudkins, E.; Kim, E.; Miltenberger, R.G.; Waters, K.A.; Jimenez, C.; Harris, M.; Stern, M. A nutrition education intervention to improve eating behaviors of children with autism spectrum disorder: Study protocol for a pilot randomized controlled trial. Contemp. Clin. Trials 2022, 26, 1436–1450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).