Abstract

The major objective was to investigate the protective capabilities of endophytic bacterial strains isolated from a number of medicinal plant species towards Aspergillus spp. secured from the internal tissues of fungi-infected peanuts. Among 32 fungal isolates surveyed for mycotoxin production in various culture media (PDA, RBCA, YES, CA), 10 isolates qualitatively producing AFB1, besides 10 OTA-producers, were assayed by HPLC for quantitative toxin production. Aspergillus spp. isolate Be 13 produced an extraordinary quantity of 1859.18 μg mL−1 AFB1, against the lowest toxin level of 280.40 μg mL−1 produced by the fungus isolate IS 4. The estimated amounts of OTA were considerably lower and fell in the range 0.88–6.00 μg mL−1; isolate Sa 1 was superior, while isolate Be 7 seemed inferior. Based on ITS gene sequencing, the highly toxigenic Aspergillus spp. isolates Be 13 and Sa 1 matched the description of A. novoparasiticus and A. ochraceus, respectively, ochraceus, respectively, which are present in GenBank with identity exceeding 99%. According to 16S rRNA gene sequencing, these antagonists labeled Ar6, Ma27 and So34 showed the typical characteristics of Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Bacillus subtilis and Bacillus velezensis, respectively, with similarity percentages of 99–100. The plant growth-promoting activity measurements of the identified endophytes indicated the production of 16.96–80.00 μg/100 mL culture medium of IAA. Phosphate-solubilizing capacity varied among endophytes from 2.50 to 21.38 μg/100 mL. The polysaccharide production pool of bacterial strains ranged between 2.74 and 6.57 mg mL−1. P. aeruginosa Ar6 and B. velezensis successfully produced HCN, but B. subtilis failed. The in vitro mycotoxin biodegradation potential of tested bacterial endophytes indicated the superiority of B. velezensis in degrading both mycotoxins (AFB1-OTA) with average percentage of 88.7; B. subtilis ranked thereafter (85.6%). The 30-day old peanut (cv. Giza 6) seedlings grown in gnotobiotic system severely injured due to infection with AFB1/OTA-producing fungi, an effect expressed in significant reductions in shoot and root growth traits. Simultaneous treatment with the endophytic antagonists greatly diminished the harmful impact of the pathogens; B. velezensis was the pioneer, not P. aeruginosa Ar6. In conclusion, these findings proved that several endophytic bacterial species have the potential as alternative tools to chemical fungicides for protecting agricultural commodities against mycotoxin-producing fungi.

1. Introduction

Multiple outbreaks involving a large number of illnesses have been attributed to the consumption of contaminated agricultural products. The majority of well-documented outbreaks are associated with parasites, viruses and bacteria. However, little attention has been paid to the potential public health risks arising from the presence of various pathogenic and/or toxin-producing fungi in the food commodities. This is despite the fact that most farm products consumed in developing countries are often cultivated by farmers with no formal education or sufficient knowledge about safe and hygienic crop cultivation practices.

Numerous fungal genera, particularly Aspergillus, Fusarium and Penicillium, have the ability to infect a wide range of field crops, including legumes. Their growth often results in the production of secondary metabolites known as mycotoxins. These naturally synthesized fungal products have attracted global attention due to their sever economic implications, which directly impact human health, animal productivity and international food trade [1,2]. These metabolites are responsible for a variety of diseases in humans, ranging from allergic reactions to immunosuppression and even cancer [3]. The term “mycotoxin” was first introduced in the 1960s during investigations into the cause of numerous deaths among Turkish people in England following the consumption groundnut meal. The toxic agent was later identified as aflatoxin B1 (AFB1) [4]. AFB1 is widely recognized for its carcinogenic, mutagenic and immunosuppressive effects, which have been documented in several studies [5,6]. Aspergillus flavus, an opportunistic plant pathogen, is known to be a primary producer of aflatoxins such as AFB1 and AFB2. It can grow on various agricultural commodities, including cereals (e.g., wheat and maize), as well as cotton, nuts and spices [7]. Mycotoxins such as aflatoxin, citrinin, ergot alkaloids, fumonisins, ochratoxin a, patulin, trichothecenes and zearalenone are among the most common toxins associated with both human and veterinary diseases. As reported by [8], food contamination depends on several factors, including AF vulnerability, prevailing environmental conditions, the fungal community present, and their ability to penetrate foods matrices.

Actually, the prevention and mitigation strategies implemented to restrict/avoid aflatoxin presence have been extensively investigated. Effective pre-harvest measures include crop genetic modification, optimized irrigation regimes, and crop rotation. Additionally, the use of non-toxicogenic Aspergillus strains, such as the commercial products Afla-guard and Afla-safe has shown promising results. Post-harvest methods involve adequate control of storage conditions, particularly through reduced water activity and temperature, alongside with sorting and eliminating contaminated seeds [9]. However, when aflatoxin contamination persists, special procedures must be applied to foodstuffs, such as degradation or inactivation through adsorption or physical/chemical treatment. These techniques have been reported to negatively affect the nutritional properties and overall quality of food, in addition to increasing production costs. In this context, the biological degradation of AFs has attracted substantial attention as a valuable and practical alternative to physico-chemical strategies. It offers several benefits, including minimal loss of product quality, safety, efficiency and a more economical and eco-friendlier approach [10,11].

OTA is another toxic mycotoxin produced by several fungal genera, including Aspergillus (e.g., A. carbonarius, A. niger, A. ochraceus), Penicillium (P. verrucosum) and Fusarium spp. [12]. These toxins were identified by South African scientists in 1965 [13]. The production of OTA by fungal species is strongly influenced by environmental factors such as temperature, pH, moisture content and water activity (aw), which are critical factors necessary for mold germination and growth on nutrient-rich substances [14]. Ochratoxins are commonly present in a wide range of food products, such as coffee, cocoa beans, chocolate, nuts, dried fruits, chili sauce, ham, spices, cereals and their byproducts, poultry, cheese, milk, pork meat and salami, beer and other produts [15,16,17,18,19,20,21]. Fortunately, the adoption of advanced agricultural technologies, proper agricultural manufacturing practices and safe storage conditions can significantly reduce the risk of OTA contamination. Good Agricultural Practices (GAP) include appropriate crop cultivation and rotation, efficient irrigation system, the proper use of agrochemicals (fertilizers and pesticides), timely harvesting and using fungi-resistant crop genotypes [22]. The excessive use of chemical pesticides has shown negative impacts on both the quality and quantity of food. In response, alternative biological methods that pose no threat to consumers’ health or the environment are highly recommended. Specific groups of microorganisms, e.g., bacteria, fungi and yeasts, as well as certain natural compounds produced by plants—like essential oils and phenolic compounds—have demonstrated the ability to degrade, transform, or absorb OTA, and are increasingly being used worldwide [14].

Over the past decades, numerous species of bacteria and fungi have been successfully exploited in the management of mycotoxins contamination. These include non-toxigenic strains of Aspergillus flavus [23], Mycobacterium fluoranthenivorans [24], Rhodococcus erythropolis [25], Pseudomonas putida [26], Streptomyces sp. [27], Rhodococcus pyridinivoruns [28] and Pontibacter sp. [29] in addition to some saprophytic yeasts [30]. Several Bacillus spp. have also demonstrated strong capabilities in controlling the growth and mycotoxin production of many filamentous fungal genera [31]. In this context, Bacillus licheniformis CFR1 notably reduced AFB1 by ca. 95% and significantly eliminated the mycotoxin-induced mutagenicity. These findings highlight the bacterium as an excellent candidate in the field of food safety and quality enhancement [32].

Peanut (Arachis hypogaea L., family: Fabaceae) is among the most prominent and popular food and oilseed crops worldwide. However, this legume is a trading commodity susceptible to a variety of bacterial and fungal diseases, resulting in yield losses and reduced quality [33]. The majority of peanut diseases are attributed to fungal infection, e.g., damping-off (Aspergillus sp., Fusarium oxysporum, Rhizoctonia solani, Rhizopus sp.), leaf blight (Alternaria tenuissima), root rot (F. moniliforme), crown rot (A. niger) and pod rot (R. solani) [34]. Several procedures, including fungicide treatment, biological control and resistant genotype breeding, have been adopted over the past few decades [35]. So far, treatment with certain species of microorganisms has proved as promising and environmentally friendly strategy for preventing/alleviating plant diseases.

Endophytes are a unique group of microorganisms that have the ability to invade and colonize various plant organs (roots, stems and leaves). They are widely recognized for their capabilities of inhibiting and suppressing many host plant pathogens, accelerating seed germination, supporting seedling development and stimulating plant growth and yield. Thus, they are considered more applicable and suitable as biocontrol agents. Among them, Bacillus spp. and Pseudomonas spp. represent the endophytic pioneers as plant growth-promoting rhizobacteria, and their bioformulations are strongly recommended in biocontrol programs. As reviewed by [36], Bacillus spp., as multifunctional organisms, were reported to produce several antibiotics such as bacteriocin and subtilisin that inhibit the growth of fungal pathogens. B. subtilis successfully restricted A. parasiticus growth and aflatoxin production by up to 92 and 100%, respectively. Similarly, B. amyloliquefaciens exhibited extraordinary capability to degrade the aflatoxins B1, B2, G1 and G2 after a period of co-cultivation. P. fluorescens also showed an ability to reduce AFB1 production by the fungus A. flavus in peanut culture medium by ca. 99%. Moreover, the endophyte P. protegens AS15 isolated from rice grains significantly reduced aflatoxin production and mycelia biomass of A. flavus by 82.9 and 68.3%, respectively.

In light of the above-mentioned data, the present work provides an insight into the possible alleviation of growth and toxin production by pathogenic fungi responsible for pod rot of peanut plants via endophytic bacteria. Hopefully, the outcomes of the study might help in adopting efficient endophytic consortia for formulating novel biofungicides to rationalize the excessive use of chemically synthetic fungicides commonly applied for controlling the legume-phytopathogenic fungi, particularly those producing exotoxins.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Soil

Soil used in the present study was taken from Nobaria fields, Behera governorate, commonly cultivated with peanut, with no recorded history of peanut pod rot diseases. It is sandy in texture and characterized by the following: organic matter, 0.8%; available N, 18.0 ppm; available P, 18.0 ppm; available K, 102 ppm; EC, 1.53 dSm−1 and pH, 8.6; based on methods described by Carter and Gregorich [37].

2.2. Peanut Pod Samples

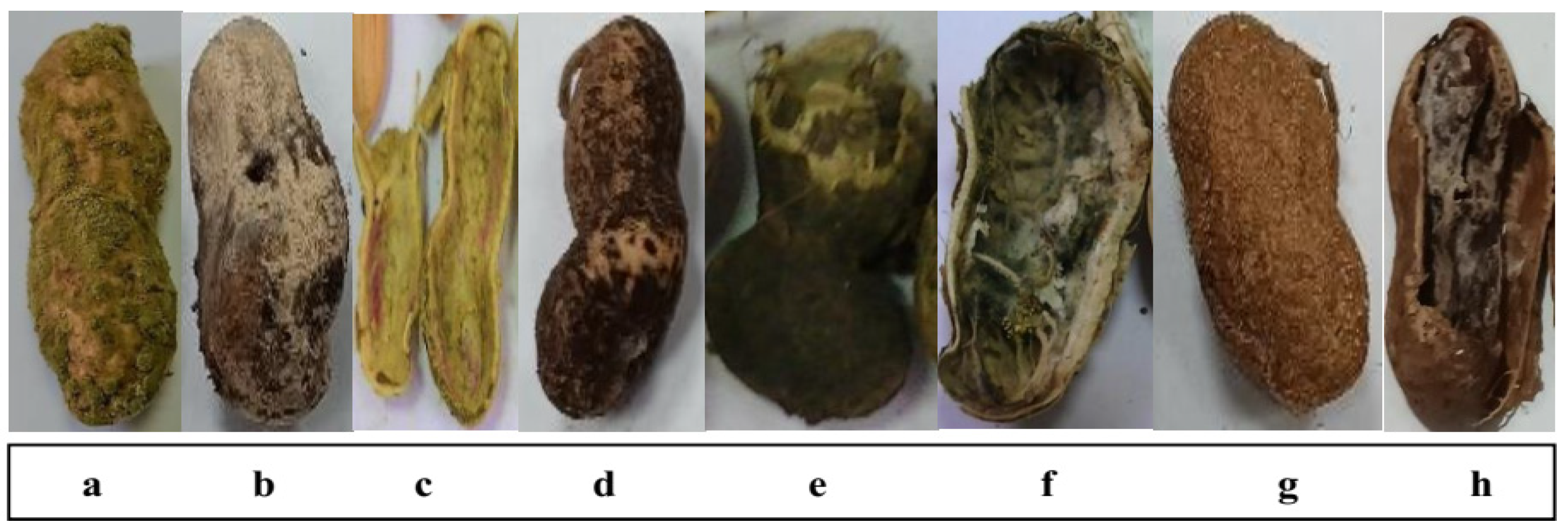

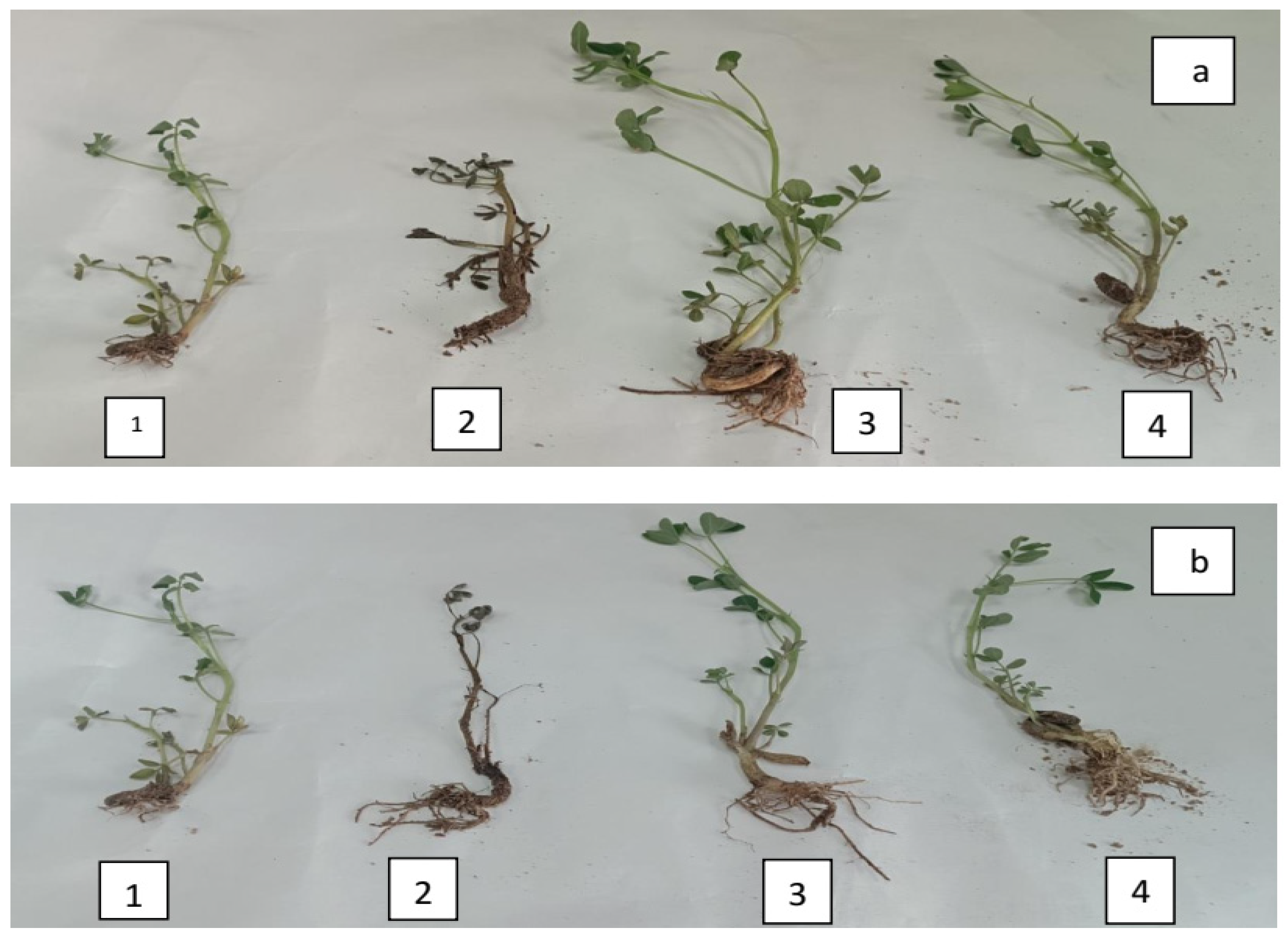

Thirteen peanut (Arachis hypogaea L.) pod samples showing rot disease symptoms (Figure 1) were randomly collected from different sources, including field-grown plants, local selling shops and storage facilities located in various governorates. Samples were collected in sterile paper bags, sealed properly and examined one day after collection.

Figure 1.

Infected peanut pods showing rot symptoms differed according to causal fungal species: (a), Aspergillus flavus; (b), Aspergillus tamarii; (c), Fusarium sp.; (d), Aspergillus niger; (e), Pythium sp.; (f), Aspergillus parasiticus; (g), Aspergillus ochraceus; and (h), Rhizoctonia sp.

2.3. Enumeration and Isolation of Toxin-Producing Fungi

Initially, surface-sterilized pods were determined for (a) fungal frequency, using the formula: Frequency (Fr, %) = No. of pods on which fungi are growing/total No. of pods × 100 and (b) disease incidence (DI), for non-sterilized pods, expressed as percentage of diseased pods among the total number of examined pods.

The infected pods were subjected to surface sterilization by immersion in 1% sodium hypochlorite for 2 min, washed several times in sterile distilled water, dried between two layers of sterilized filter paper and then ground in adequate amount of sterile distilled water. Spread-plate method was adopted for the enumeration of fungi, where the homogenized pod suspensions were 10-fold serially diluted in sterile distilled water up to 10−4. Aliquots of 0.1 mL dilutions were deposited, in triplicate, on potato dextrose agar (PDA) plates for counting total molds and Aspergillus spp. as well as on yeast extract sucrose (YES) agar for toxigenic Aspergillus types [38,39]. After incubation at 28 °C for 5–7 days, plates of 10–100 colonies were selected and counted as CFUs g−1. The relative density percentage (RD%) of toxigenic Aspergillus spp. was calculated as RD% = No. of the genus colonies/No. of total fungi × 100.

From developed colonies, 62 representative isolates were randomly selected and purified by successive transfers several times on PDA medium. Pure isolates were cultivated on rose bengal chloramphenicol agar (RBCA) medium and incubated at 28 °C for 5 days.

2.4. Toxin-Producing Ability of Aspergillus spp. Isolates

The toxigenic capabilities of the 62 pathogenic isolates of Aspergillus spp. were examined using the method described by [40] as follows: a single fungal colony was allowed to grow at the center of a Petri dish containing YES medium for 5 days at 28 °C. Thereafter, plates were exposed to ammonium hydroxide vapor by adding 2 drops of 27% solution to the inverted lid of the plate and kept in dark for 30 min. The formation of pink to plum-red color on the underside of fungal colony indicates positive reaction. The production of fungal toxins was further confirmed on coconut agar (CA) medium using the procedure of [41]. A portion of 100 g shredded coconut was homogenized in 200 mL hot distilled water for 5 min. The mixture was stirred and filtered by cheese cloth. The pH of the filtrate was adjusted to 6.9 using 2N NaOH, 2% agar was added then autoclaved at 121 °C for 15 min. Single fungal colonies were introduced on centers of agar plates containing CA medium and incubation took place at 28 °C for 7 days. When the reverse sides of plates exposed to UV at 365 nm, the presence/absence of fluorescence indicates a toxigenic/atoxigenic isolate. The toxigenic ones that absorbed and emitted fluorescence were categorized as strong (+++)-, moderate (++)- and weak (+)- toxin producers based on fluorescence intensity.

2.5. Pathogenicity of Selected Aspergillus spp. Isolates Towards Peanut

Among the 62 isolates tested on YES and CA media, 32 isolates that exhibited positive results on both media were further selected for pathogenicity against peanuts. Fungal suspensions were prepared from 7-day old cultures where spores were added to 10 mL of 1% NaCl (w/v) solution containing 5% tween-80 (w/v). Decimal serial dilutions were prepared in sterile peptone solution to ensure a concentration of ca. 106 spores mL−1.

Fresh and healthy peanut seeds cv. Giza 6 obtained from the Field Crops Research Institute, Agricultural Research Center, Giza, were surface-sterilized in 1% sodium hypochlorite for 2 min followed by several washes in sterile distilled water. Seeds were partially hydrated by immersion in sterile distilled water up to ca. 20% water content and assayed for possible fungal infection by direct plating technique of [42]. In triplicate, 10 moistened seeds were wounded by flamed sterile needles and inoculated at the wounds with fungal spores; control seeds were treated with sterile distilled water. Both treated and untreated peanut seeds were placed in sterile Petri dishes and kept in the dark at 28 °C. After 10 days, seeds were examined for surface mycelial growth coverage under an Olympus SZ61 stereoscopic microscope (Olympus corporation, Tokyo, Japan).

2.6. Quantification of the Aflatoxigenic and Ochratoxigenic Potentials of Selected Pathogenic Fungal Isolates

Among the 32 fungal isolates assessed for pathogenicity against peanut seeds, only 20 were successful in the test. Based on conidial colors of those isolates on PDA plates, ten aflatoxin B1 (AFB1) producers characterized by green coloration and ten ochratoxin A (OTA)-producers by yellow coloration were selected for quantitative toxin production using high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC), according to the method described by [43] with slight modifications. Aliquots of 10 µL of fungal isolates were centrally inoculated onto PDA plates and incubated in the dark at 30 °C for 10 days. The produced toxins were then extracted following the method described by [44]. A total of 1000 µL of methanol was added into Eppendorf tubes containing five mycelial plugs and mixed using a vortex. Tubes were incubated at ambient temperature for 30 min., followed by centrifugation (Spectrofuge 16 M, Labnet, Edison, NJ, USA) at 10,000× g for 5 min.

The HPLC analysis was performed at Central Laboratories Network, Desert Research Center, Cairo, Egypt, using a Thermo System (Ultimate 3000) (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) consisting of a pump, automatic sample injector, and associated DELL-compatible computer supported with Chromeleon7.2.10 interpretation software. A diode array detector DAD-3000 (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) was used. The Thermo-hypersil reversed phase RP-C18 column (2.5 × 30 cm) temperature was operated at 30 °C and 40 °C for AFB1 and OTA, respectively. The mobile phase consisted of a mixture of water–methanol–acetonitrile (60:20:20) for AFB1 and acetonitrile–water–acetic acid (50:49:1) for OTA. The fluorescence detector was monitored at 365 nm and 330 nm excitation, and the UV absorption spectra of the standards as well as the samples were recorded at 244 nm and 254 nm for AFB1 and OTA, respectively. Samples and standard solutions as well as the mobile phase were degassed and filtered through 0.45 µm membrane filter (Millipore). An injection volume of 20 µL and a flow rate of 0.8 mL/min were employed during the analysis process. The identification of the compounds was performed by comparing their retention times and UV absorption spectrum with those of the standard [45].

2.7. Morphological Features of the Extremely Toxigenic Aspergillus spp. Isolates

The two most toxigenic Aspergillus spp. isolates (labeled Be13 and Sa1) producing AFB1 and OTA, respectively, were first identified to the species level based on their colony morphology such as color, texture, and surface appearance as well as microscopic observations of the fungal features including head seriation, conidial shape and size. These phenotypic traits were examined using standard mycological identification techniques [46,47], which were performed with a compound bright-field light microscope (Olympus CX23, Olympus Corporation, Japan). To confirm their identity, both isolates were subsequently analyzed using molecular methods.

2.8. Source and Isolation of Endophytic Bacteria

A total of 60 endophytic bacteria were isolated from the internal tissues of 12 medicinal plants: argel (Solenostemma argel), basil (Ocimum basilicum), cumin (Cuminum cyminum), drum sticks (Moringa olerifera), ginger (Zingiber officinale), ginseng (Panax quinquefolius), roselle (Hibiscus sabdariffa), rosemary (Rosmarinus officinalis), rue (Peganum harmala), sage (Salvia officinalis), spearmint (Mentha viridis) and thyme (Thymus vulgaris). These plants were taken from private fields located at 9 governorates (Table 1). Shoot and root portions were tap-water-washed, surface-sterilized by immersion in 95% ethanol for 30 s, followed by 30 min immersion in 3% sodium hypochlorite, and then thoroughly washed with sterilized distilled water. Plant materials were triturated for 5 min in a waring blender in appropriate amounts of sterile distilled water and decimal serial dilutions were prepared. To select the endophytes capable of degrading toxins, one mL of either dilution was introduced into Petri dishes filled with 15 mL coumarin nutrient agar medium (CNAM), incubation was carried out at 25 °C for 48 h [48].

Table 1.

Endophytic bacterial isolates taken from different medicinal plant species and successfully cultivated on coumarin nutrient agar medium (CNAM).

Developed colonies were picked up, purified by successive sub-culturing on the same medium, and preserved as pure isolates at 4 °C. After purification, isolates were subjected to morphological characterization. The morphological properties included cell shape, Gram staining and motility testing, which were carried out according to standard protocols described by Cappuccino and Sherman [49]. For Gram staining, bacterial smears were prepared on clean glass slides, heat-fixed, and then stained with crystal violet for 1 min. After rinsing with water, Gram’s iodine was applied for 1 min to form a complex with the primary stain. The slides were then decolorized with 95% ethanol for 10–15 s and counterstained with safranin for 30 s; the slides were rinsed again, air-dried and examined under a light microscope. Gram-positive bacteria retained the crystal violet and appeared purple, whereas Gram-negative bacteria lost the primary stain and took up the safranin, appearing pink/red.

2.9. Antibiosis Potentials of Endophytes Against Aspergillus spp. Isolates

The in vitro antifungal activities of 36 endophytic isolates, successfully grown on CMNAM among the examined 60 colonies, towards the fungal isolates Be13 and Sa1, were monitored using the paper disk diffusion method. An amount of 1 mL fungal suspension (ca. 106 spores mL−1) was introduced into test tube containing 15 mL melted PDA medium and poured into Petri dishes in triplicates. After solidification, 5 mm diameter sterile paper disks spotted with 10 µL endophytic bacterial culture suspension (ca. 107 cells mL−1) were placed on agar surface, and plates were then incubated at 25 °C for 10 days. The diameters of inhibition zones were measured daily, and the absence of mycelium mass indicated complete suppression. Fungal inhibition (FI) percentage was calculated as well using equation FI % = (R − r)/R × 100, where R is radial growth of fungi in control plate, and r is the radial growth of fungi in endophytic treated plates [50]. The three pioneer endophytic antagonists (labeled Ar6, Ma27 and So34) were selected for molecular identification.

2.10. Molecular Identification of Selected Toxigenic Fungi and Endophytic Antagonists

Molecular identification of selected microorganisms was performed using the internal transcribed spacer (ITS) region of nuclear ribosomal DNA for toxigenic fungi and 16S rRNA gene sequencing for endophytic antagonists.

Toxigenic fungal isolates were grown on PDA medium and incubated at 28 °C for 5 days. Similarly, endophytic bacterial isolates were cultured on nutrient agar (NA) medium at 30 °C for 72 h. Genomic DNA was extracted from agar-grown cultures using the Quick-DNA Fungal/Bacterial Microprep Kit (Zymo Research; D6007, Irvine, CA, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. DNA extraction and sequencing were conducted by Macrogen, Incorporation, Seoul, Republic of Korea, a Public Biotechnology Company for Research Services.

PCR amplification was performed using the Maxima Hot Start PCR Master Mix (Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA; K1051). The fungal ITS region was amplified using the forward primer ITS5-F (5′ GGA AGT AAA AGT CGT AAC AAG G-3′) and the reverse primer ITS4-R (5′-TCCTCCGCTTATTGATATGC-3′). Bacterial 16S rDNA gene was amplified using primers 27F (5′ AGA GTT TGA TCM TGG CTC AG-3′) and 1492R (5′-TAC GGY TAC CTT GTT ACG ACT T-3′). PCR conditions included an initial denaturation at 95 °C for 10 min, followed by 35 cycles of denaturation at 95 °C for 30 s, annealing at 57 °C for 30 s and extension at 72 °C for 1.5 min; a final extension phase was performed at 72 °C for 10 min. A total of 50 µL total PCR reaction contained the following: 25 µL Maxima Hot Start PCR Master Mix (2×), 1 μL of each primer at a concentration of 2 μM, 5 µL of template DNA and 18 µL nuclease-free water. PCR products were purified using Gene JET PCR Purification Kit (Thermo Scientific; K0701), following the manufacturer’s protocol. DNA sequences were analyzed using BioEdit software (version 7.2.5) and compared to the NCBI GenBank (National Center for Biotechnology Information) through BLASTn tool (https://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Blast.cgi; accessed on 15 June 2025) to identify the closest matching species. Phylogenetic trees were constructed using the maximum likelihood method in Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis MEGA 11 [51].

2.11. Plant Growth-Promoting Activities of Identified Endophytic Bacteria

The plant growth-promoting capabilities of the identified endophytic candidates were limited for the following assessments:

- 1.

- Indole acetic acid production:The indole acetic acid content was determined according to Bric et al. [52] with modifications. Bacterial endophytes were grown in nutrient broth containing 1 mM tryptophan at 28 °C for 3 days. After centrifugation, the supernatant was mixed with orthophosphoric acid and Salkowski’s reagent. The pink color developed was measured at 530 nm, and IAA concentration was determined using a standard curve.

- 2.

- Phosphate dissolving efficiency:Bacterial endophytes were qualitatively screened for phosphate solubilization by inoculating them on modified pikoviskaya agar medium. The formation of a clear zone around the colonies was observed after an incubation at 30 °C for 4 days was estimated. Quantitative estimation was carried out by inoculating 1 mL of bacterial suspension into Bunt and Rovira broth medium supplemented with 0.9 g rock phosphate per 100 cm3 medium. The cultures were incubated at 30 °C for 10 days, then centrifuged at 6000 rpm for 15 min, and the supernatant was then used to determine the concentration of dissolved following the method adopted of [53].

- 3.

- HCN production:HCN production was assessed following Geetha et al. [54]. King’s B agar medium supplemented with 4.4 g/L glycine was sterilized and poured into plates. Each isolate was streaked in triplicate plates. Whatman No. 1 filter paper pads soaked in 2 mL of picric acid solution (12.5 g/L Na2Co3, 2.5 g/L picric acid) were placed on plate lids. The plates were sealed with parafilm and incubated at 30 °C for 7 days. HCN production was evaluated based on color change in the filter paper: no change (−), brown (+), brownish-orange (++) or complete orange (++++), indicating increasing HCN levels.

- 4.

- Production of exo-polysaccharides (EPS):Endophytes were cultured in sucrose broth medium at 30 °C. After incubation, cells were centrifuged at 6000 rpm in 1 Mm EDTA. The supernatant was mixed with equal volume of cold acetone to precipitate EPS. The precipitate was collected by centrifugation at 6000 rpm for 30 min, dried at 60 °C and weighed as described by [55].

2.12. Afla-/Ochratoxin Degradation by Endophytic Bacterial Strains

The ability of tested endophytic antagonists to degrade AFB1 and OTA in culture medium was assessed using the method described by [56]. Two disks (8 mm) of toxigenic fungal growth representing either Be13 or Sa1 isolates were introduced into 50 mL YES broth medium; this was followed by inoculation with either the endophytes Ar6, Ma27 or So34. Incubation lasted 15 days at 28 °C in the dark, with fungi-YES culture medium without bacteria allocated as control. Mixed cultures were then centrifuged (12,000 rpm, 3 min, 4 °C) and filtered through 0.22 μm pore size membrane. The residual amounts of toxins were quantified by HPLC using the formula of [11]:

2.13. The Endophyte–Pathogen Interweave Affecting Peanut Seedling Development

Adopting the gnotobiotic model, the antifungal potentials of the superior bacterial endophytes (Ar6, Ma27 and So34) against the most aggressive Aspergillus spp. (isolates Be13 and Sa1) were evaluated in relation to peanut seedling growth. Glass tubes of 40 cm in length and 5 cm in diameter were filled with 260 g of sandy soil, then autoclaved at 121 °C for 20 min. Surface-sterilized seeds of peanut cv. Giza 6 were germinated on Petri dishes containing water-moistened cotton pieces for 3 days. Aseptically, two well-developed seedlings of similar sizes were introduced into the tube where the roots were gently dipped down into holes. Hoagland nutrient solution [57] with half the recommended level of nitrogen source was added at a rate equivalent to 60% WHC of soil. An amount of 2 mL spore suspension (ca. 106 spores mL−1) of either fungal pathogen was added. Thereafter, 2 mL freshly prepared inoculum of Bradyrhizobium japonicum (ca. 106 cells mL−1), obtained from Agricultural Research Center, Giza, were distributed over the soil. In addition, 2 mL of either endophyte suspension (ca. 107 cells mL−1) was uniformly spread on soil surface. Seedling tubes were kept at ambient temperature for one month and received sterile Hoagland solution when needed. The experimental layout comprised 12 treatments, in triplicates, representing all the possible interactions between the endophytes and toxigenic fungi (Table 2). The 30-day-old seedlings were measured for length and fresh weights of shoots and roots, in addition to the number of Aspergillus spp. and endophytes in soil counted by using agar plate technique.

Table 2.

Layout of gnotobiotic experiment encompassing the various interactions between toxigenic fungi and endophytes.

2.14. Statistical Analysis

Data were subjected to statistical analysis using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA). Comparisons among means were performed using Duncan’s multiple range tests at p ≤ 0.05 significance level according to [58]. Standard deviation (SD) was calculated to express the variability within replicates.

3. Results

3.1. Disease Attributes of Fungi-Infected Peanut Pods

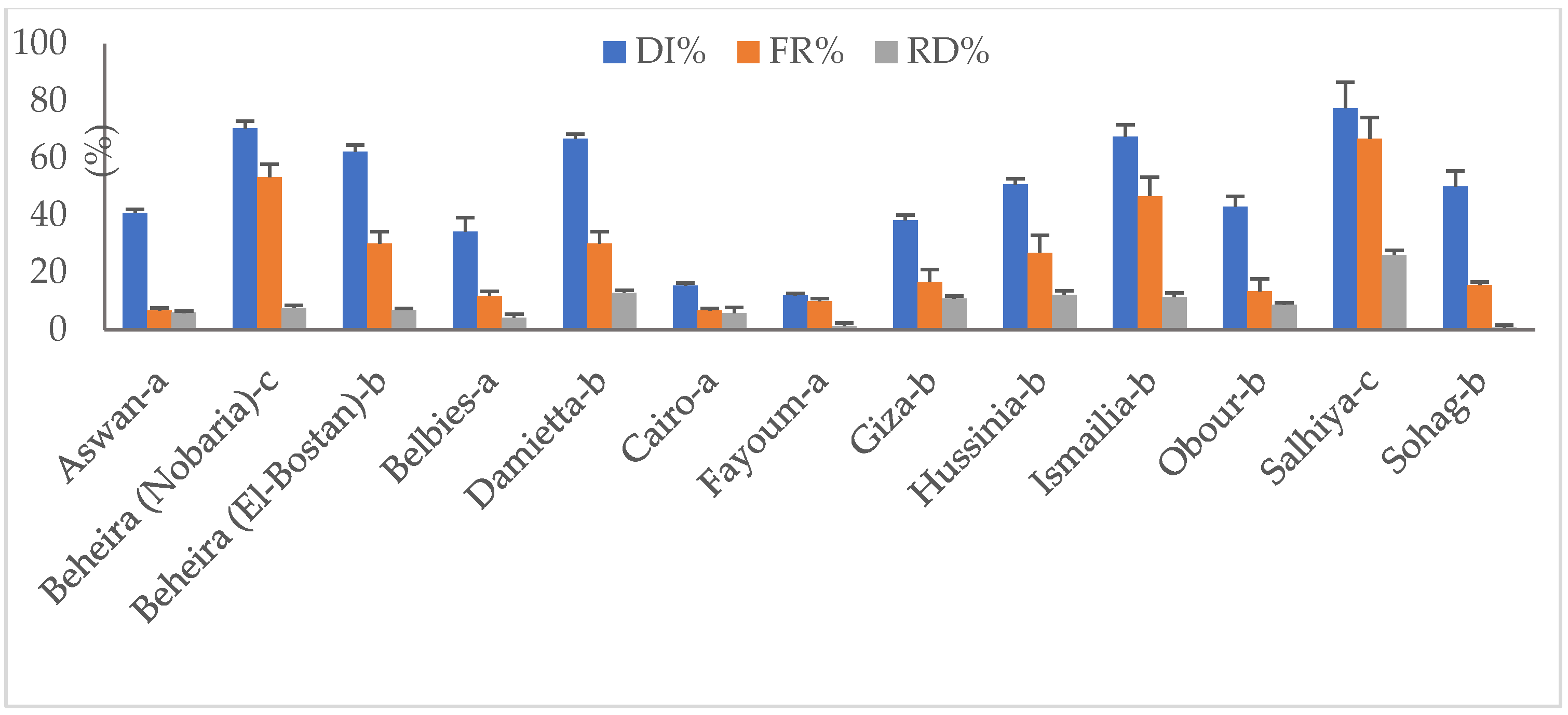

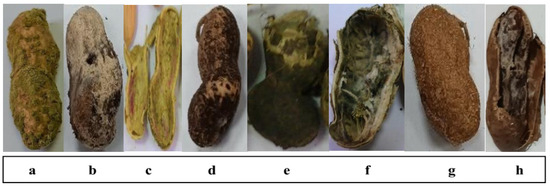

Fungal disease traits of 13 representative pod samples showing rot disease symptoms are illustrated in Figure 2. Apart from sampling source, rot disease incidences (DI) ranged from 11.9% to 77.5%. Pods obtained from Salhiya severely infected by pathogenic fungi recorded the highest DI %, followed by those of Beheira (Nobaria) (70.4%), while Fayoum pods had the lowest DI level. Fungal frequency (Fr) percentages significantly varied among sources and were estimated at 6.7–66.8%. Samples of Aswan and Cairo appeared more hygienic than others and recorded a 6.7% frequency. As expected, pods collected from Salhiya field-grown legume exhibited the highest frequency level of 66.8%. Irrespective of sampling source, stored peanut pods reported average frequency percentages of ca. 26.

Figure 2.

Disease attributes (%) of fungi-infected peanut pods collected from different sources: (a) selling shops, (b) stores, (c) field-grown plants. DI, disease incidence; FR, frequency; RD, relative density.

Diverse fungal community monitored for the surface-sterilized legume plant pods is presented in Figure 3. Total molds (TMC) were enumerated as high as 150 CFU g−1 for the Salhiya field sample, Beheira (Nobaria) pods ranked thereafter (131 CFU g−1). Samples of Cairo and Fayoum accommodated the lowest TMC load of 59 CFU g−1, while other pod samples hosted 80–129 CFU g−1 of TMC. Aspergillus spp. population represented variable levels among the whole fungal community. The pathogen counts were highest for the Salhiya field pods at 83 CFU g−1, representing ca. 55% of TMC. The pathogen load in the total population was the lowest (<30%) in Cairo and Fayoum samples and the highest (>60%) for pods taken from Damietta. Irrespective of sampling source, the toxigenic Aspergillus spp. colonies developed on yeast extract sucrose agar medium averaged 10.6 CFU g−1, representing 26.4% of total fungus density. An exceptional occurrence of toxigenic members (39 CFU g−1) was found in the Salhiya field pods. The relative density of toxigenic candidates to TMC did not exceed 12.9% for the majority of pod samples, but was estimated at 26% for those from Salhiya.

Figure 3.

Fungal community composition of surface-sterilized peanut pods of the experimented samples. TMC, total mold counts; AC, Aspergillus spp. counts; TAC, toxigenic Aspergillus spp. counts.

3.2. Prevalence of Toxigenic Aspergillus spp. Infecting Peanut Pods

Sixty-two Aspergillus spp. isolates were secured from surface-sterilized and ground-infected peanut pod samples and allowed to grow on PDA and RBCA media for 5 days at 28 °C. Seen by the naked eye, the color of fungal colonies somewhat indicates the pod-infecting species. A yellowish-green color characterizes A. flavus, green represents A. parasiticus, dark yellow indicates A. ochraceus, white-brown color represents A. tamari, while A. niger produces black-colored conidia. Supplementary Table S1 reveals the great variability in colony colors among the isolates. On PDA, the majority of developed colonies (29%) appeared yellowish-green, indicating a higher presence of A. flavus compared to the other species. In contrast, A. tamarii forming white-brown colonies rarely cultured (11%). The colony colors of fungal members slightly differed when cultivated on RBCA medium. When screened for the ability to produce extracellular toxins on both yeast extract sucrose (YES) and coconut agar (CA) media, 32 isolates (ca. 52%) tested positive to the reactions. Based on fluorescence intensity under UV light at 365 nm, six isolates screened as strong toxin-producers (+++), six as moderate-producers (++) and twenty as weak producers of mycotoxins (+).

3.3. Quantitative Production of Aflatoxin B1 (AFB1) and Ochratoxin A (OTA) by Toxigenic Aspergillus spp.

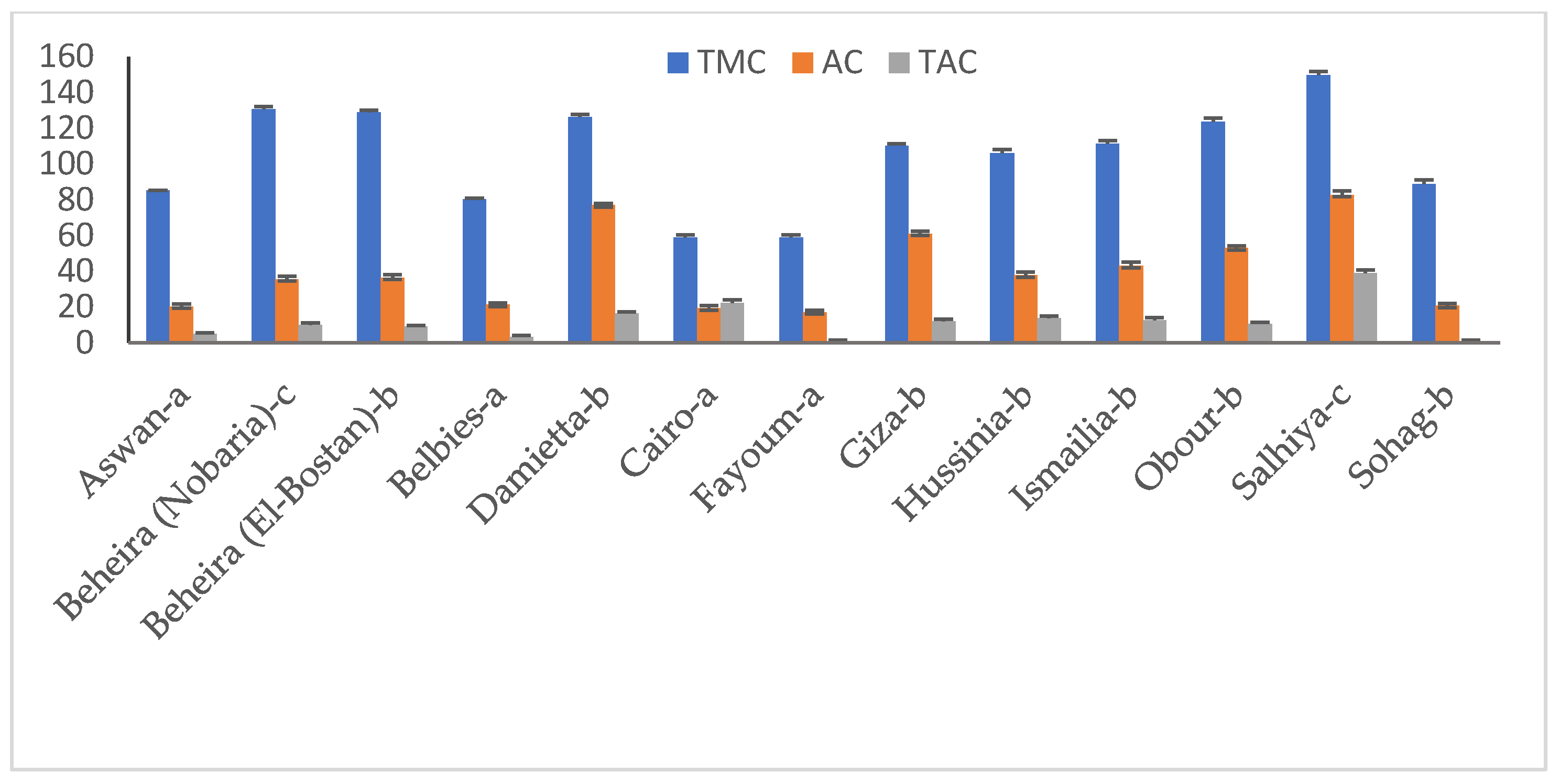

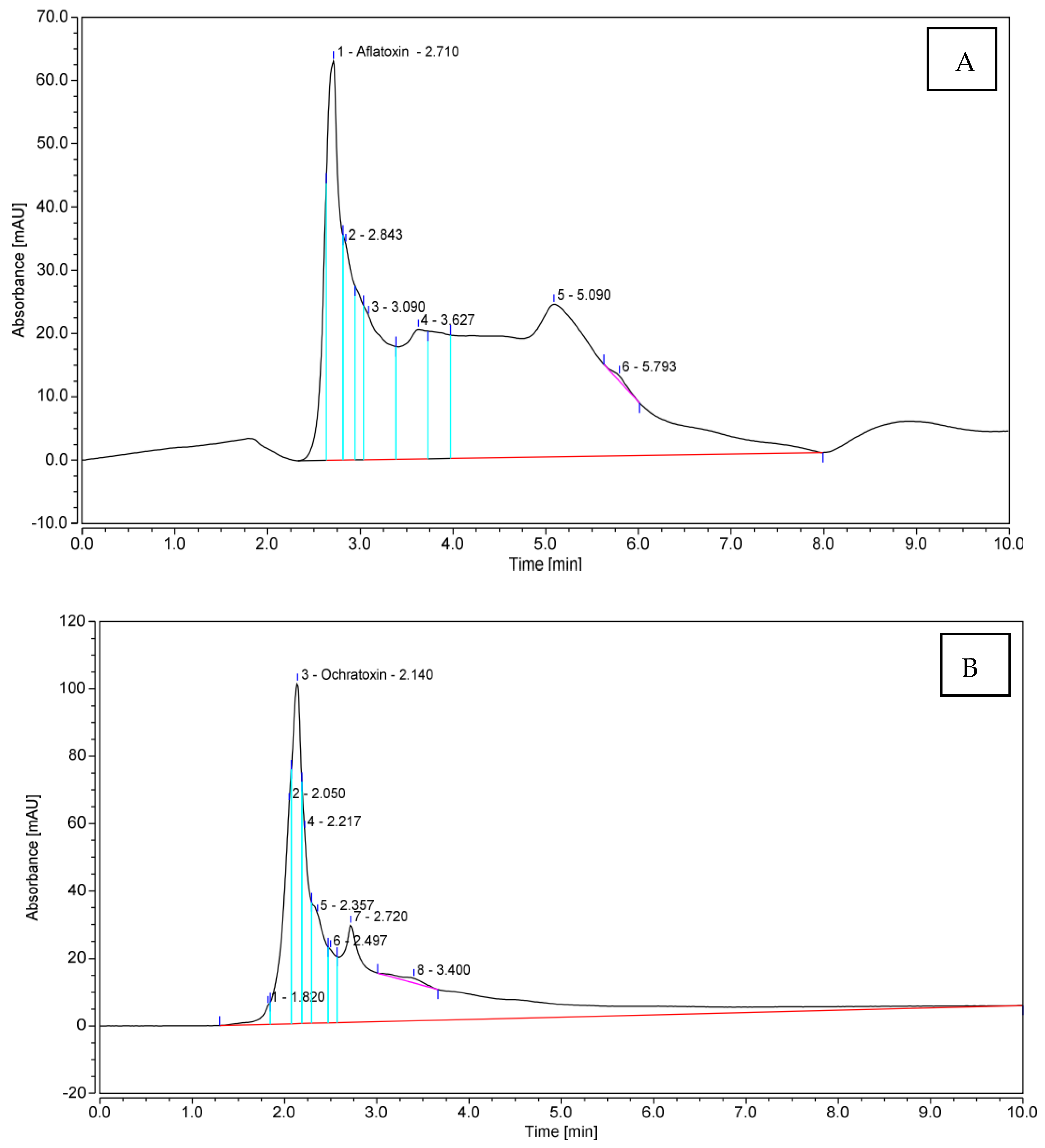

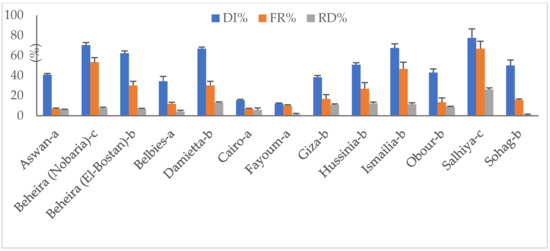

Referring to the previous pre-selection of 32 toxigenic Aspergillus spp. isolates nicely grown on YES and CA culture media, 10 isolates producing AFB1 in addition to 10 OTA-producers, were assessed for quantitative toxin production by HPLC analysis. With respect to AFB1, extraordinary quantities of the toxin were produced by the tested isolates (Table 3). An amount of 1859.18 μg mL−1 was produced by Aspergillus spp. isolate Be13; another potent producer was isolate So2, which yielded 1162.74 μg mL−1 of AFB1. On the contrary, Aspergillus spp. isolate IS 4 was the inferior one, producing the lowest quantity of the toxin (280.40 μg mL−1). The remaining eight fungal candidates produced AFB1 in amounts falling in the range of 304.91–696.92 μg mL−1. The amounts of OTA produced by the examined pathogenic fungi were considerably lower than those of AFB1, and varied from 0.88 to 6.00 μg mL−1. The fungus isolate Sa1 was superior, while isolate Be7 was the inferior one. Figure 4 illustrates the flow charts of HPLC analyses for mycotoxins produced by the most toxic fungal members.

Table 3.

Quantitative determinations of aflatoxin (AFB1) and ochratoxin (OTA) produced by the selected toxigenic Aspergillus spp. isolates.

Figure 4.

HPLC flowcharts ofAFB1 and OTA produced by Aspergillus spp. isolates Be13 (A) and Sa1 (B), respectively.

3.4. Morphological Features and Molecular Identification of AFB1- and OTA-Producing Isolates

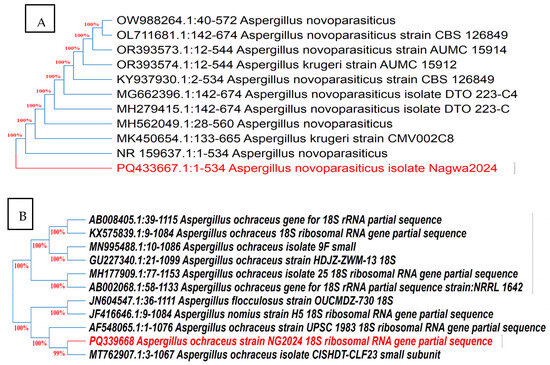

The cultural and microscopic characteristics of Aspergillus isolates Be13 and Sa1 producing AFB1 and OTA, respectively, are presented in Supplementary Table S2. Molecular identification based on ITS gene sequencing (Figure 5) revealed more than 99% similarity with reference sequences of Aspergillus novoparasiticus and Aspergillus ochraceus strains, respectively, in GenBank. These sequences were deposited in GenBank under the accession numbers PQ 433667 and PQ339668, respectively.

Figure 5.

Neighbor-joining trees based on ITS gene sequencing of toxigenic fungal isolates Be13 (A) and Sa1 (B). Trees show the relationships of isolates to closely related fungi recovered from GenBank. Both isolates shared more than 99 identities with closest phylogenetic relatives.

3.5. Endophytic Microbiome of Medicinal Plants

Seventy-three samples representing 12 medicinal plants were subjected for isolation of the endophytic microbiomes of both plant compartments (endo-phyllospheres and endo-rhizospheres). When introduced into coumarin nutrient agar medium, 60 isolates successfully grown indicating their ability to use coumarin as a carbon source, a chemical substrate as a precursor for both afla- and ochratoxin biosynthesis.

Out of those assessed for antibiosis towards the toxigenic fungal isolates Be13 and Sa1 on PDA medium, 36 appeared positive on the test (Figure 6, Table 4). The majority originated from the endorhizospheres of tested plants. As to the endophyte effect, regardless of fungal members, the pioneer endophyte antagonists could be arranged in the following descending order: isolate So34 (av. 18 mm, representing inhibition percentage of 21.8), Ar6 (17 mm, 19.9%) and Ma27 (15 mm, 17.9%). In general, fungal isolate Sa1 seemed more susceptible for the endophytic antagonists than the other one, where average inhibition zone diameter of 8.4 mm was measured for the former against 5.9 mm for the latter.

Figure 6.

Antifungal activity of the superior endophytes against the toxigenic fungi Aspergillus novoparasiticus Be13 (A) and Aspergillus ochraceus Sa1 (B).

Table 4.

Antibiosis of endophytic bacterial isolates towards the toxigenic fungal pathogens Aspergillus novoparasiticus Be13 and Aspergillus ochraceus Sa1.

3.6. Taxonomic Position of Selected Endophytic Bacterial Isolates

The microscopic examinations of bacterial endophytes indicated that isolate Ar6 appeared Gram-negative, motile short rods, while isolate Ma27 was Gram-positive, motile long rods, similar to isolate So34.

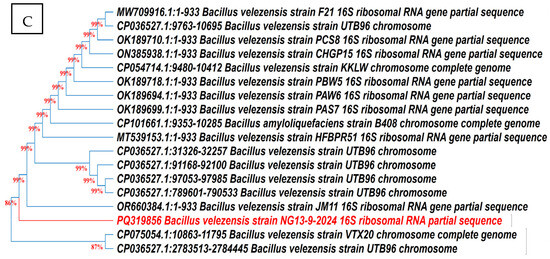

According to 16S rRNA gene sequencing and phylogenetic evaluation analysis (Figure 7), the closest relative of the endophyte Ar6 was Pseudomonas aeruginosa with 100% identity. The isolate Ma27 showed the typical description of Bacillus subtilis with 100.00% similarity. Isolate So34 identified as Bacillus velezensis with 99.00% similarity. The three identified endophytic antagonists were deposited in GenBank under the accession numbers PV798377, PV798378 and PQ319856, respectively.

Figure 7.

Phylogenetic trees of the endophytic antagonists Ar6, Ma27 and So34 identified as Pseudo monas aeruginosa (A), Bacillus subtilis (B) and Bacillus velezensis (C), respectively, based on 16S rRNA gene sequencing.

3.7. Plant Growth-Promoting Properties of the Endophytes

The tested endophytic bacterial strains exhibited several plant growth-promoting traits including production of indole acetic acid, polysaccharides and hydrogen cyanide, as well as phosphate solubilization (Table 5). Extraordinary quantity of indole acetic acid approximated 80 μg/100 mL was detected in Bacillus velezensis So34 culture medium being the highest among the examined endophytes. Bacillus subtilis Ma27 ranked thereafter with the production of ca. 38 μg/100 mL. The lowest level of the chemical compound (16.94 μg/100 mL) was produced by the endophyte Pseudomonas aeruginosa Ar6. In contrast, the performance of bacterial strains in phosphate solubilization and polysaccharide production differed significantly. A solubilization activity as high as 21.38 μg/100 mL P was estimated for P. aeruginosa, while the lowest rate of 2.50 mg/100 mL was shown for B. velezenesis. An appreciable solubilization pattern of 17.13 µg/100 mL was achieved by B. subtilis strain. The amounts of polysaccharides produced by the endophytes were falling in the range 2.74–6.57 mg mL−1 being the highest for B. subtilis. The latter strain failed to produce hydrogen cyanide, while other strains obviously formed a storm of gas.

Table 5.

Biological activities of the antagonistic endophytic strains.

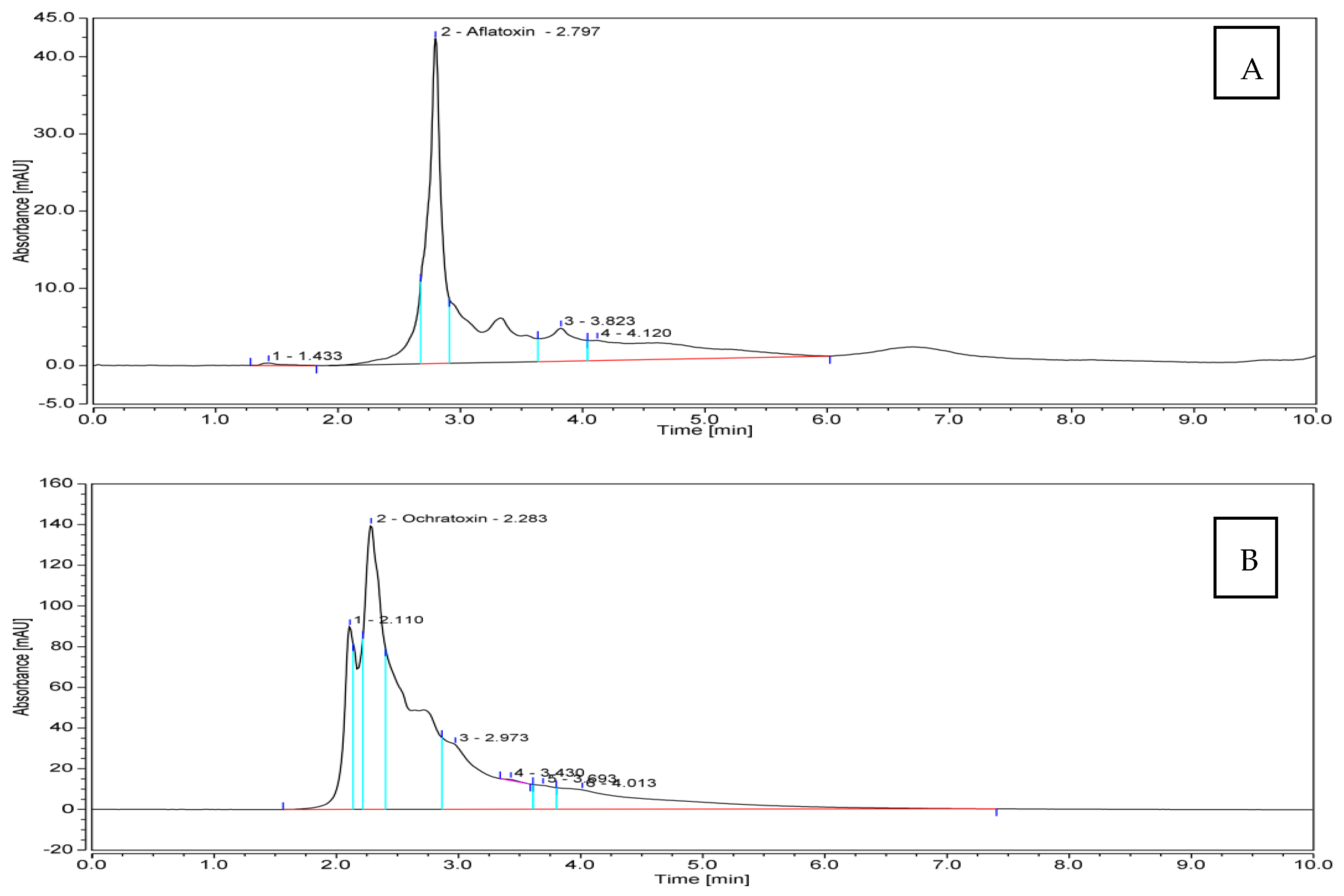

3.8. Biodegradation of Fungal Toxins by Endophytic Bacterial Strains

The in vitro mycotoxin biodegradation pattern was found to be endophyte-dependent. Apart from toxigenic fungal candidate, the endophyte B. velezensis scored the highest levels of AFB1 and OTA biodegradation with an average percentage of 88.7, followed by B. subtilis (85.6). Relatively lower efficiency of toxin degradation was reported for P. aeruginosa (av. 71.2%). No significant differences between AFB1 and OTA biodegradation rates were attributed to the antagonistic endophytes, where the biodegradation percentages of both were almost similar. HPLC chromatograms illustrated in Figure 8 speak well on the situation, with B. velezensis/toxin patterns as an example.

Figure 8.

HPLC chromatograms representing the biodegradation profiles of AFB1 (A) and OTA (B) due to the endophyte B. velezensis.

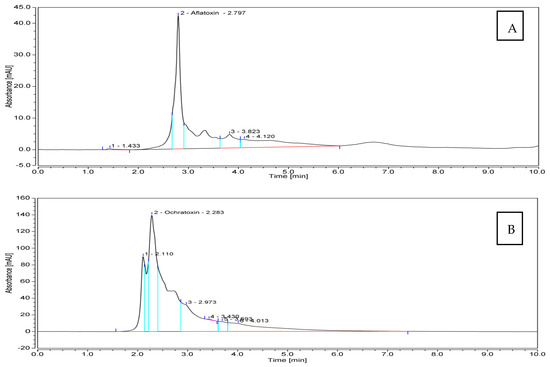

3.9. Endophytic Antagonists/Toxigenic Fungi/Peanut Panorama in Gnotobiotic System

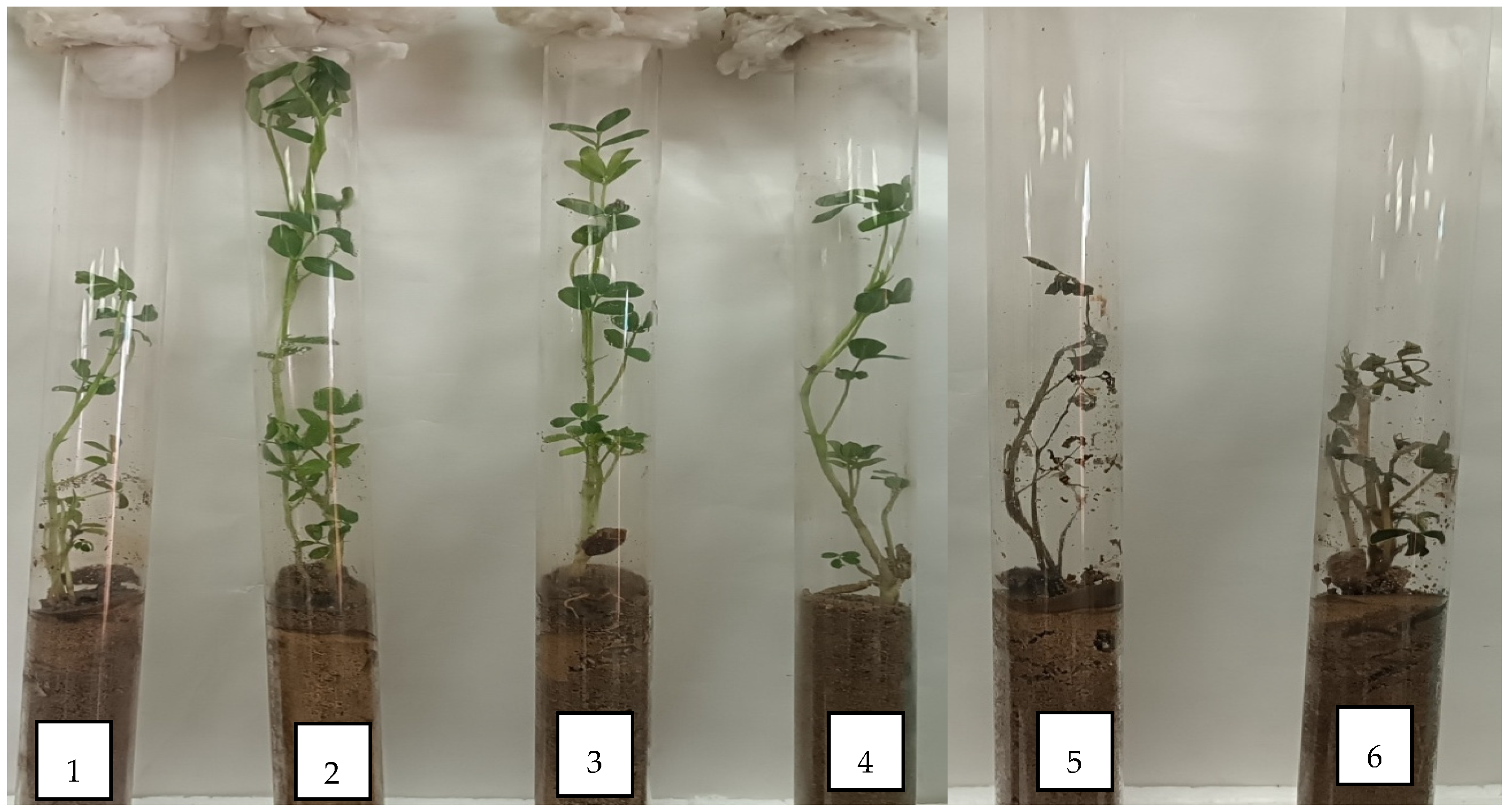

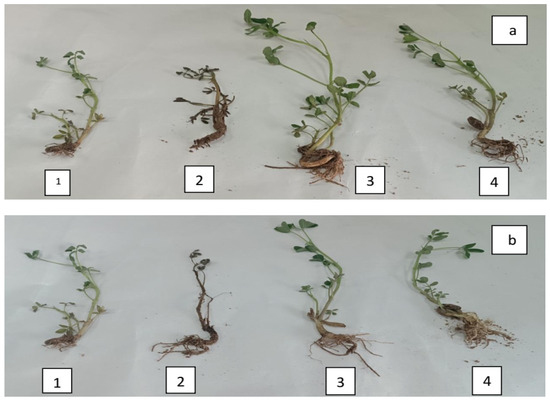

After 30 days of cultivation in sand soil applying the gnotobiotic model experiment, the peanut seedlings variably responded to treatment with either bacterial endophytes or toxigenic fungi. The apparent development and growth of the legume plant conspicuously expressed the direct effect of the allocated treatments (Figure 9). While fungi-infected seedlings developed poorly, as expected, those inoculated with the endophytes developed and appeared healthier. The promotive impact of endophytic bacteria was further demonstrated in peanuts infested with toxigenic fungal strains, where plants treated with both endophyte and the pathogen appeared to be in good condition.

Figure 9.

Apparent growth of 30-day old peanut (cv. Giza 6) seedlings with different treatments 1, control; 2, B. velezenesis; 3, B. subtilis; 4, P. aeruginosa; 5, A. ochraceus and 6, A. novoparasiticus.

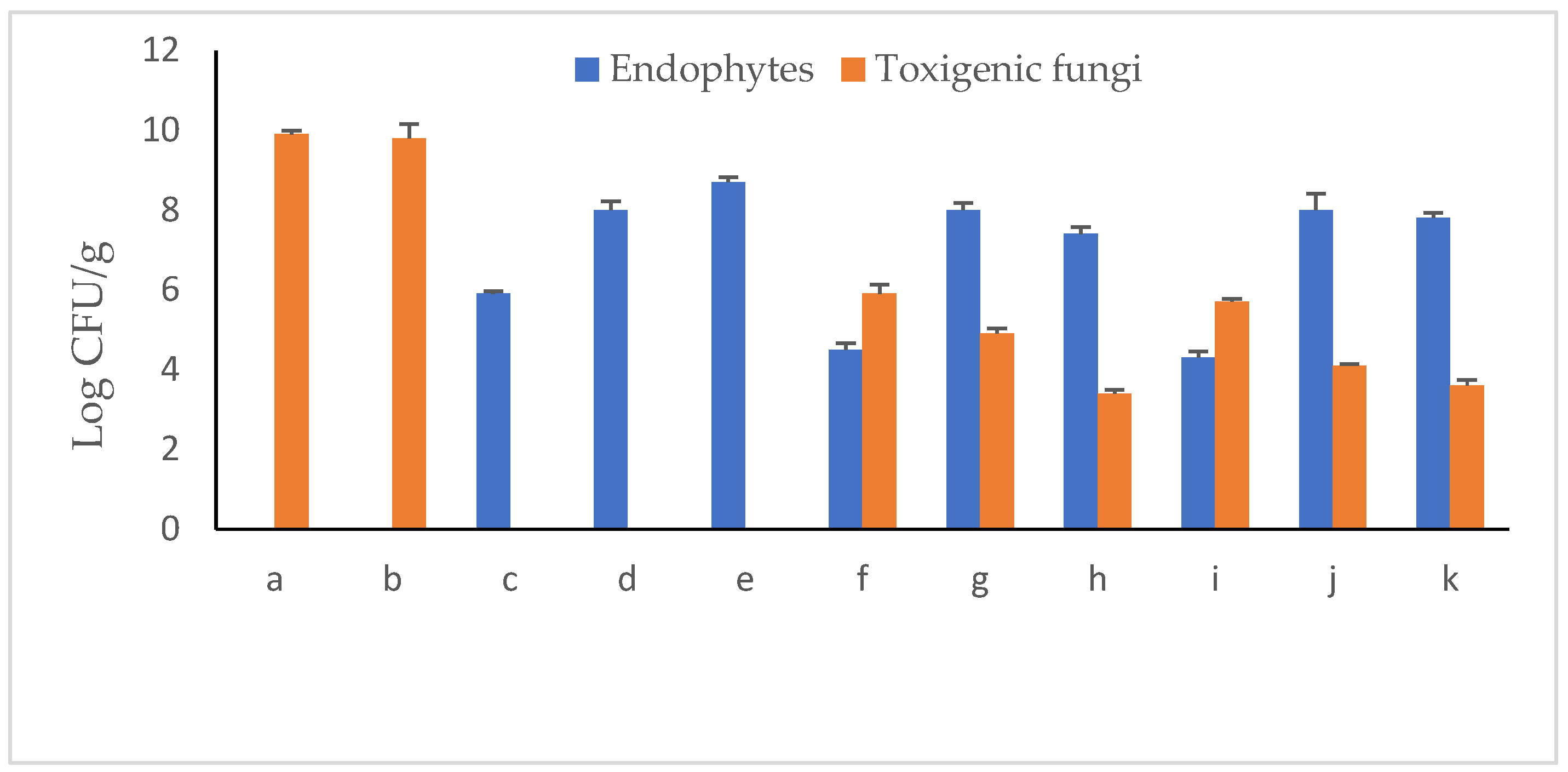

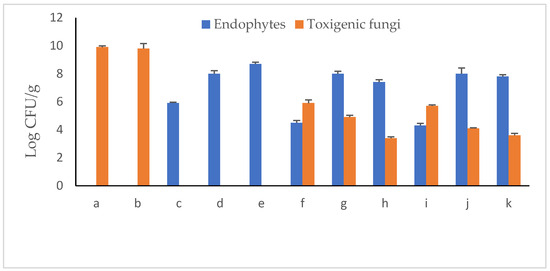

3.10. Endophytes and Fungi Populations in Legume Root Environment

Immediately following the mono-infestation of peanut seedling–soil systems with the toxigenic fungal strains A. novoparasiticus or A. ochraceus, the numbers of CFUs developed on PDA medium were log 6.8 CFU g−1 for either (Figure 10). With prolonged incubation to 30 days, counts significantly elevated to ca. log 10 CFU g−1 for both. Similarly, the initial endophyte populations were almost the same (log 7.9 CFU g−1). At the 30th growth period, estimated CFUs counts were endophyte strain-dependent. While Pseudomonas aeruginosa Ar6 decreased to log 5.9 CFU g−1, Bacillus subtilis Ma27 remained somewhat constant (log 8.0 CFU g−1). Relative increase in CFU counts of Bacillus velezensis So34 was recorded representing 10.1% of the initial load. In respect to toxigenic fungi, counts of both markedly increased up to 45% at the end of the experiment. When both microorganisms were introduced to the legume–soil system, the situation was different. P. aeruginosa was greatly injured in the presence of A. ochraceus, in particular, recording a reduction of 45.5% in its numbers. Both Bacillus strains seemed more resistant to the fungus. As to toxigenic Aspergillus spp. population in soil, no remarkable changes were observed due to the effect of the antagonist P. aeruginosa. Bacillus strains successfully restricted the multiplication rates of both fungal candidates with reduction percentages of 26.8–49.3%.

Figure 10.

Log CFU/g−1 counts of endophytic antagonists and toxigenic fungi in peanut–soil system of 30-day gnotobiotic experiment (a, A. novoparasiticus; b, A. ochraceus; c, P. aeruginosa; d, B. subtilis; e, B. velezensis; f, A. novoparasiticus + P. aeruginosa; g, A. novoparasiticus + B. subtilis; h, A. novoparasiticus + B. velezensis; i, A. ochraceus + P. aeruginosa; j, A. ochraceus + B. subtilis and k, A. ochraceus + B. velezensis).

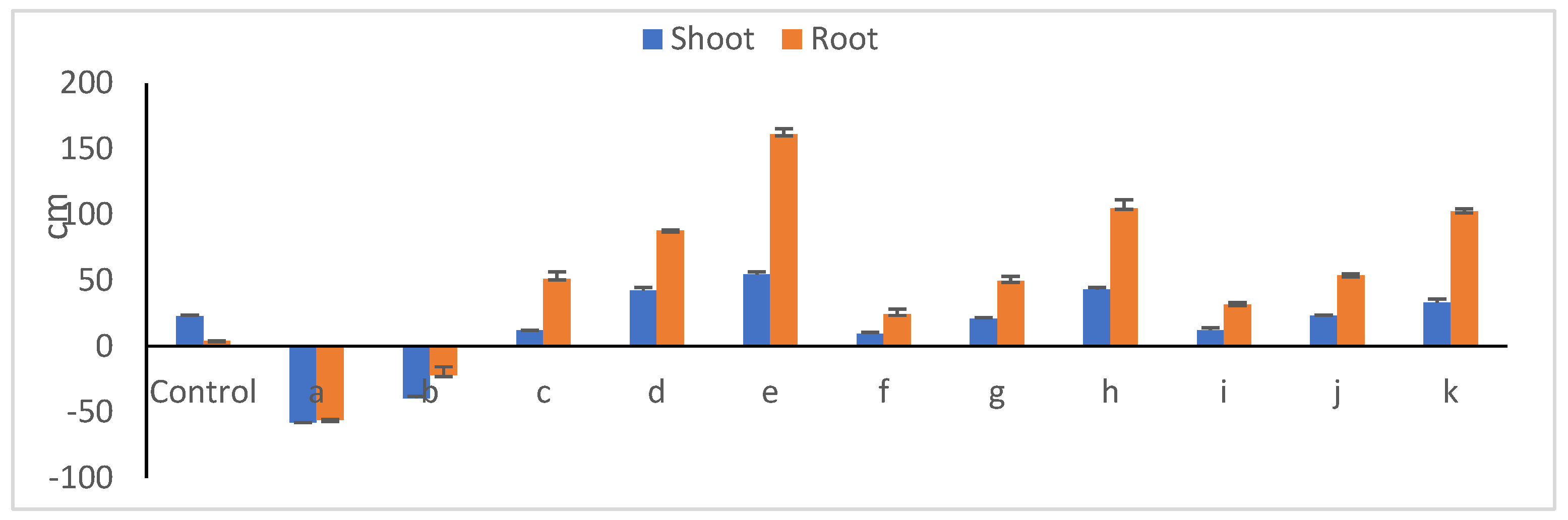

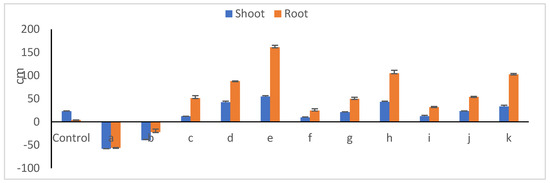

3.11. Peanut Seedling Growth Parameters in Presence of Microbial Communities

Relative changes in shoot and root lengths of 30-day old peanut seedlings due to endophyte/toxigenic fungi interweaves are presented in Figure 11. In the presence of fungal members, seedlings developed poorly (Figure 12), with the lowest shoot (av. of 11.6 cm) and root (av 2.5 cm) lengths; this is expressed in reduction percentages of 48.9 and 39.1%, respectively. The suppression impact of Aspergillus novoparasiticus Be13 exceeded that of Aspergillus ochraceus Sa1. Among the endophyte mono-cultures, Bacillus velezenesis supported the tallest shoots recording a 54.7% increase over untreated plants, an effect that extended to root system as well (a 161.2% increase). Bacillus subtilis Ma27 ranked thereafter, with respective increases of 42.6 and 87.1%. Simultaneous introduction of both microorganisms into soil diminished, to an extent, the suppressive influence of fungi towards seedling development (Figure 12). In the case of A. novoparasiticus-treated peanut, B. velezenesis was the superior one and resulted in 43.4 and 105.1% increases in shoot and root lengths, respectively. This effect was observed in A. ochraceus-treated seedlings, where respective increases of 33.6 and 52.94% were estimated. Pseudomonas aeruginosa Ar6 was the least effective (increases of less than 9.0 and 23% were estimated, respectively). Table 6 presents the fluctuations among the microbial treatments regarding shoot and root fresh and dry weights. Differences between treatments regarding fresh weights of both seedling organs were more or less similar to those reported in case of lengths. Dry matter yield, as a more reliable indicator plant growth, better reflects the impact of the applied treatments. As expected, the introduction of the toxigenic fungi, whatever the candidate, into peanut–soil system dramatically reduced the biomass production of both legume shoots and roots, an effect that was more pronounced with A. novoparasiticus, where the respective reductions in dry weights reached 84.9 and 95.7%. The harmful impact of A. ochraceus was relatively lower with 71.7 and 78.3% reductions. Exceptional increases in biomass yields were attributed to inoculation with the bacterial endophytes.

Figure 11.

Relative changes in length (cm) of peanut shoots and roots (related to untreated seedlings (a, A. novoparasiticus; b, A. ochraceus; c, P. aeruginosa; d, B. subtilis; e, B. velezensis; f, A. novoparasiticus + P. aeruginosa; g, A. novoparasiticus + B. subtilis; h, A. novoparasiticus + B. velezensis; i, A. ochraceus + P. aeruginosa; j, A. ochraceus + B.subtilis and k, A. ochraceus + B. velezensis).

Figure 12.

Comparable development of 30-day-old peanut seedlings with different treatments. (a) A. novoparasiticus/B. velezensis, (b) A. ochraceus/B. velezensis, 1, control; 2, pathogen; 3, endophyte; 4, pathogen + endophyte (an example for the pathogen/endophyte interaction).

Table 6.

Decrease/increase percentages in peanut seedling shoot and root weights as affected by the endophytic antagonists and toxigenic fungi interactions (related to untreated seedlings).

B. velezenesis was the most supportive, recording >390 and >360% increases in dry weights of shoots and roots, respectively. No obvious differences between P. aeruginosa and B. subtilis were noticed in this respect. In general, endophyte introduction to fungi-treated peanuts greatly overcame the suppressive influence of toxigenic fungi. This particular effect is expressed in exceptional increases in dry weights of shoots and roots. In respect to root/shoot ratio, on dry weight bases, the variations among treatments were mostly endophyte strain-dependent. While the narrowest ratio of 0.23, on average, was calculated for toxigenic fungi-treated legume plant, conspicuously wider ratios were estimated when endophytic bacteria were introduced into gnotobiotic model, a phenomenon that indicating higher root biomass production. In mono-bacterial cultivation media, no obvious differences were found from one strain to another; this was not the case in the presence of the pathogenic fungi, where remarkable variations were obtained. Again, B. velezenesis successfully alleviated the toxigenicity of pathogens, particularly A. novoparasiticus, resulting in higher root biomass and, in turn, a larger root/shoot ratio (0.50). On the contrary, P. aeruginosa exhibited ratios as small as 0.31 and 0.33 with A. novoparasiticus and A. ochraceus, respectively.

4. Discussion

Along the various successive steps in the farm-to-table continuum that includes cultivation, irrigation, growth, harvest, processing, packaging, transportation, handling and retain, microbial contamination is highly likely from a variety of sources, e.g., surrounding environments, animals and/or humans. This, actually, leads to large losses of crop produces, which reflects on profit, i.e., earnings are significantly affected. Great numbers of pathogenic fungi are opportunistic soil creatures that are implicated in contamination issues in the agricultural field besides being responsible for high economic losses. Among those, Aspergillus spp. is commonly infecting a variety of crops such as maize, soybean and peanuts, as well as dried fruits [8,59,60]. These particular fungal species produce several secondary metabolites encompassing a large number of exo-mycotoxins which seriously affect food sanitary quality and are established to be carcinogenic and hepatotoxic [3,61].

The global occurrence besides toxicity of mycotoxins greatly attracted the attention of some national and international organizations. In this respect, the European Food Safety Authority (EFSA) and the United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA) have established a number of rules and guidelines for addressing the fungal toxin issue in food products. For example, while the European Union (EU) set the permissible limit of 15 µg kg−1 for total aflatoxins in nuts including peanut, the FDA set the maximum level of 20 µg kg−1 [62]. Aflatoxins are the most common mycotoxins, mainly recognized as B1, B2, G1 and G2 [36]. Ref. [63] mentioned that that poisoning comes from ingesting aflatoxin-containing foods has been identified either as acute, severe intoxication that causes direct liver damage or chronic sub symptomatic exposure.

Ochratoxins, similarly, are mycotoxins produced by some molds, particularly those belonging to the genera Aspergillus and Penicillium [14]. Ochratoxin A (OTA) is best-known due to its widespread occurrence and high stability. OTA contaminates several agricultural products such as cereals, coffee, wine, beer, tea, fruit juices, etc. [64,65,66]. Carcinogenicity, genotoxicity, hepatotoxicity, immunotoxicity, neurotoxicity and teratogenicity represent the main toxic effects of OTA [67].

Mycotoxin-producing fungi have been reported to significantly reduce both the quality and quantity of peanut yield due to their ability to invade pods and produce harmful toxins that affect seed viability and safety [35]. The combined legume yield losses due to incidence of fungal diseases were as high as ca. 50%. This dramatic situation highlights the urgent need to adopt an appropriate strategy to avoid the expected harmful effects of toxigenic fungi on the legume plant production. A great number of synthetic antifungal chemical compounds or preservatives have been extensively used for many decades to control mycotoxin contamination in foodstuff; such chemicals are hazardous to both consumers and the environment. Here, other control strategies that are effective, non-toxic and environmentally friendly are a necessity. Therefore, the last few decades witnessed the development of biological detoxifying procedures to support food safety for direct consumption. Several microorganisms proved to have strong bioactive characteristics to control mycotoxin-producing fungi [36]. In this context, a great number of bacteria, particularly those of endophytic nature, were reported to possess great capabilities to inhibit/restrict the growth of fungal pathogens invading several plant species [68,69,70]. Bacillus subtilis CW14 exhibits strong antifungal activity against A. ochraceus, achieving an inhibition rate of 85.7%. Further investigation revealed that the antifungal compounds produced by CW14 interfered with mycelium growth and spore formation, induced chitin accumulation, triggered a cellular stress response and changed the morphology and quantity of hyphae and spores [71]. Bacillus velezensis, isolated from the bulbs of Lilium leucanthum, showed antifungal activities against plant pathogens like Botryosphaeria dothidea, Fusarium oxysporum, Botrytis cinerea and Fusarium fujikuroi [72].

Owing to semi-tropical climate of Egypt, where the temperature remains between 25 and 35 °C with relative humidity of 30–40% during peanut growth season, the environment is favorable for mycotoxin-producing Aspergillus spp. to contaminate pods and seeds of peanut besides producing afla- and ochratoxins. Accordingly, the need arose in the present study to verify the prevalence and potential of fungi that might associate with peanut during cultivation in respect to their capability to produce toxins of public health implication. When 13 randomly selected fungi-infected pod samples collected from different sources were examined for disease indexes, disease incidence (DI), frequency (Fr) and relative density (RD), those collected from field-grown plants appeared severely infected, compared to the corresponding ones taken from commercial shops which were relatively safer. From colonies developed on PDA and YESA media, 62 isolates were secured, and all were belonging to the genus Aspergillus. Based on colony colors, 29% of isolates belonged to A. flavus, while A. parasiticuwas rarely found. Upon introduction into coconut agar (CA) medium, 32 isolates appeared to be extracellular toxin-producers. In this respect, ref. [73] recorded the abundance of Aspergillus spp. (A. flavus; A. fumigatus; A. niger; A. parasiticus), Mucor spp., Penicillium spp. and Rhizopus spp. in ground nuts selected from various markets at Zimbabwe. Also, ref. [74] isolated Aspergillus spp., Mucor spp., Penicillium spp. and Rhizopus spp. from groundnuts collected from local markets in Kenya. In an extensive survey conducted by [75], 25 out of 29 samples of animal feed cultured on PDA medium exhibited the prevalence of Aspergillus flavus. The isolates A. niger, Fusarium spp., Herminthosporium spp., Mucor spp., Penicillium spp., Rhizopus spp. and Trichoderma spp. were common as well. The authors mentioned that the dominance of Aspergillus spp. is attributed to it being widespread in the environment as a result of its capability to produce plenty of reproductive units tolerant to the prevailing conditions which form airborne plankton, in addition to growing at wide ranges of humidity and temperature of 5–50 °C or sometimes higher.

When YES-developed Aspergillus spp. colonies in the present study were exposed to ammonium vapor, they showed plum red/pink color, indicating that they are AFB1-/OTA-toxin producers. The color intensity identified Aspergillus spp. to be as high/low toxic. Visual observations revealed that 18.8% of isolates were highly toxic, 18.8% were moderately toxic, while 62.4% seemed least toxic. In accordance with these findings, ref. [75] reported ML6 and NG8 A. flavus isolates revealing high intensity of fluorescence ring, while isolates CH4, Ch7, ML9, ML11, MY5 and NG3 showed moderate color intensity; compared to CH11, MY1, MT2 and MY3 had less intensity of fluorescence ring on CA medium.

Ten isolates producing AFB1 and 10 producing OTA were assessed for quantitative production of toxins using high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC). Results indicated considerably high levels of 280.40–1859.18 µg mL−1 AFB1 being Aspergillus isolate-dependent. The quantities of OTA produced were significantly lower (0.88–6.00 µg mL−1). Preliminary screening for aflatoxin production by several Aspergillus isolates conducted by [3] revealed the detection of 93.40–106.39 µg kg−1 in coconut agar medium compared to 83.16–99.67 µg kg−1 in potato dextrose broth. On the other hand, ref. [66] reported an accumulation of OTA in corn and wheat plants in quantities of 187–611 µg kg−1 due to infection with Aspergillus spp. and Penicillium spp.

Based on ITS gene sequencing, the highly AFB1- and OTA-producing fungal isolates secured in the present study fitted the description of Aspergillus novoparasiticus Be13 and Aspergillus ochraceus Sa1, respectively. A total of 60 endophytic bacterial isolates were obtained from endorhizospheres and endophyllospheres of 12 various medicinal plant types, and examined for the possible antagonistic potentials towards the highly toxigenic fungal isolates. The superior theee endophytic antagonists were identified via 16S rRNA gene sequencing as Pseudomonas aeruginosa Ar6, Bacillus subtilis Ma27 and Bacillus velezensis So34. The identified endophytic bacteria exhibited high biological potential, including indole acetic acid, exo-polysaccharides and hydrogen cyanide production, in addition to phosphate solubilization. These findings confirm those of [76], who reported appreciable quantities of indole acetic acid and a high rate of phosphate solubilization obtained by several endophytic bacterial strains belonging to Pseudomonas spp. and Serratia spp. Also, ref. [77] recorded antagonistic effects of Bacillus subtilis strains EFS3, EFS9 and EFS13 against Aspergillus spp., Fusarium spp. and Penicillium spp., together with improving the quality of some food raw materials due to production of biologically active substances. A comprehensive investigation was carried out by [78] on the ability of numerous endophytic microorganisms to produce plant growth-promoting substances in addition to their antibiosis potential towards some toxigenic fungal species. A total of 32 bacterial isolates out of 156, representing the seed, root and rhizosphere microbiomes of sugar beet, were selected and assayed for in vitro plant growth-promoting activities, including N2-fixation; P-solubilization; siderophore, IAA and HCN production; enzymatic activities (amylase, cellulase, gelatinase, lipase, mannanase, pectinase, protease, xylanase); mitigation of environmental stresses (salinity, drought); in addition to antifungal activities. The results indicated that Bacillus subtilis KO3-18, Curtobacterium pusillum ED2-6, Mixta theiocola KO3-44 and Providencia vermicola ED3-10 exhibited the highest plant growth-stimulating effects due to their multiple capabilities. The endophytes Bacillus halotolerans C3-16/2.1, Bacillus velezensis C3-19 and Paenibacillus polymyxa C3-36 showed the highest antagonistic impacts against the phytopathogens Fusarium spp. (F. coffeatum IP32; F. denticulatum IP39; F. equiseti TS3; F. falciforme IP31; F. foetens IP27; F. graminearum CIK, GDI, S3-7; F. ipomoeae; F. nigamai TS6; F. oxysporum S4-2; F. oxysporum TS2; F. semitectum; F. solani TS8; F. subglutinans; F. venatum CIK; F. verticilloides K67 5.1.) and Cercospora beticola TS4. Pseudomonas aeruginosa isolated from the leaves of Achyranthes aspera L. had plant growth-stimulating attributes including siderophore, indole acetic acid release and inorganic phosphate solubilization; it also exhibited antifungal property against Rhizoctonia solani. This study emphasizes the role of P. aeruginosa AL2-14B in stimulating growth of A. aspera L. and the improvement of its medicinal properties [79].

Globally, among all mycotoxins, aflatoxins and ochratoxins represent a great threat to humans, plants and animals that resulted in the adoption of a number of food regulations for protecting the public health. In this context, food safety refers to the procedures/conditions that maintain the quality of food aimed at preventing contamination and food-borne diseases. It is expressed as an integrated “farm to fork” concept that includes human welfare, plant health, food production and processing, animal nutrition and health, storage, transport and export, as well as retail sales [33]. Peanut, as a principal trading commodity, is exposed to phytopathogen attacks that lead to sever losses in terms of productivity [80]. Due to the negative effects of using physical and chemical procedures on the quality/quantity of food products, biological strategies using microorganisms are considered a significant shift away from the conventional techniques. Here, a great variety of endophytic bacteria are nesting the internal tissues of some plants without any deleterious effects on their development or productivity. In such plant repositories, the endophytes modify/improve the host tolerance to biotic and abiotic stresses [81]. Therefore, a part of the present study introduces an answer to the raised question, are endophytic microorganisms able to alleviate the harmful impact of toxigenic fungi on peanut?

A gnotobiotic model experiment was designed to expound how far the endophytic bacterial strains P. aeruginosa Ar6, Bacillus subtilis Ma27 and Bacillus velezensis So34 can protect/support peanut development and growth against the toxigenic Aspergillus spp. invasion. The microbial community composition in the legume plant–soil system of 30-day-old seedlings speaks much of the high antibiosis potential of tested endophytes towards the pathogens. This is expressed in the high reduction in numbers of CFUs of fungi in the presence of the endophytic antagonists; Bacillus velezensis So34 was the superior compared to others. On the other hand, among the endophytes, the OTA-producer Aspergillus ochraceus Sa1 appeared more susceptible to endophyte attacks than Aspergillus novoparasiticus Be13. In this context, ref. [81] screened the antagonistic effects of 15 endophytic Bacillus spp. strains against the phytopathogens Fusarium graminearum and Macrophomina phaseolina. Bacillus spp. WS 1-16, WS 1-25 and WS 1-23 exhibited the strongest antibiosis patterns compared to the other strains, an effect that is attributed to the production of antimicrobial agents based on microbial metabolite. The produced antifungal metabolites were tetradecanoic acid [82]; 2,5-piperazinedione; 3,6-bis (2-methylpropyl) [83]; 9-octadecenamide (z) [84]; n-hexaadecanoic acid [85] and hexane-1,3,4-triol, 3,5-dimethyl [86]. Strikingly, the antagonistic effect of Bacillus spp. towards toxigenic fungi was not limited to the suppression of pathogen growth but extended, as well, to some morphological changes where mycelia exposed to bacterial methanolic extract showed thinning, less branching and non-germinated microsclerotia in M. phaseolina. Lysis of fungal cell walls is among the antagonistic mechanisms that bacterial species employ. Reference [87] reported that the chitinolytic Serratia marcescens strain JPPI isolated from peanut hulls is an active antagonist against Botrytis cinerea, Fusarium oxysporum and Rhizoctonia solani due to its ability to produce chitinase enzyme. The reseaerch of [88] confirmed the remarkable effect of the hydrolytic enzyme chitinase on reducing the growth and pathogenicity of toxigenic fungi. Additionally, ref. [77] reported that, when fungal pathogens were exposed to bacilli antagonists, several morphological changes in the mycelium structure of micromycetes were observed, which presented as increases and swelling of hyphae, extensive vacuolization, together with the presence of some cells devoid of cytoplasm. Generally speaking, as previously mentioned by [89], the detoxification of afla-/ochratoxins by biological agents includes two main processes, i.e., absorption and decadence (degradation). Either AFB1 or OTA could be absorbed by microorganisms via concatenation to cell wall constituents through effectual internalization or congregation.

In addition to restricting the multiplication/pathogenicity of A. novoparasiticus Be13 and A. ochracceus Sa1, the endophytic antagonists successfully supported the peanut development; this resulted in nicely grown and taller seedlings, an effect that varied from one endophyte to another. While B. velezensis So34 was the most efficient against both mycotoxin-producing A. novoparasiticus Be13 and A. ochraceus Sa1 strains, the bacterium Pseudomonas aeruginosa Ar6 had the lowest antagonistic effect. The endophyte/pathogen-interaction also reflected on the legume root and shoot biomass yields. In the absence of bacterial antagonists, fungi-infected peanuts showed dramatic reductions in shoot and root dry weights of 71.7–84.9 and 78.3–95.7%, respectively. Exceptional increases in dry weights of both plant organs were attributed to simultaneous treatment with the endophytes.

Biological degradation of mycotoxins occupies significant role in the detoxification strategies of exo-toxin-producing fungi. As observed by HPLC analyses, the endophyte B. velezensis So34 successfully degraded both AFB1 and OTA at the high rates of 86.48 and 90.81%, respectively. Biodegradation percentages for other endophytic candidates were lower. Average estimates of 71.20 and 85.57% were recorded with P. aeruginosa Ar6 and B. subtilis Ma27, respectively. In accordance to this, ref. [90] reported the ability of B. amylolyticus, B. schafferii, B. subtilis and B. velezensis to detoxify AFB1. Reference [91] recorded high levels of OTA reduction in culture medium inoculated by B. subtilis KU-153. Biodegradation efficiencies of 52.9 and 59.0% were estimated by B. subtilis for OTA in contaminated maize and lentil, respectively, but lower levels of 18.7 and 41.2% were attributed to P. fungorum [92]. B. subtilis WJ6 exhibited high capability to degrade AFB1 in the presence of high levels of the toxin in shorter catalytic time [93]. According to ref. [94], the degradation rate of AFB1 by P. aeruginosa reached 99.67% in moldy maize. As mentioned by [95], Actinobacter tandoii DSM 14970 successfully hydrolyzed the amide bond of OTA yielding non-toxic OTα and L-β-phenylalanine due to the degrading enzyme carboxypeptidase PJ15-1540.

5. Conclusions

The selected endophytic bacterial isolates represent promising candidates for the use as starter cultures that possess a broad spectrum of activities/antagonism, thus showing high potential for the development of efficient and applicable biocontrol formulations. Further studies are needed to monitor the quantitative inhibitory impacts against AFB1 and OTA production on peanuts. In addition, dedicated efforts should focus on testing the compatibility of potent bacterial strains, forming viable “bottom-up” consortia and testing their effects on the legume plant development and productivity, as well as toxigenic pathogen survival/resistance under field conditions.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/microbiolres16070141/s1, Table S1: Colony colors and toxigenicity of fungal members isolated from infected peanut pods collected from different sources; Table S2: Cultural characteristics and microscopic observations of toxigenic fungal isolates grown on PDA medium.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, N.I.M.H., M.H.B., A.M.E.-H., M.K.M.A. and M.F.; methodology, N.I.M.H., M.H.B., A.M.E.-H., M.K.M.A. and M.F.; software, N.I.M.H., M.H.B., A.M.E.-H., M.K.M.A. and M.F.; validation, N.I.M.H., A.M.E.-H., M.K.M.A. and M.K.M.A.; formal analysis, N.I.M.H., M.K.M.A., M.H.B., A.M.E.-H., M.K.M.A. and M.F.; investigation, N.I.M.H., M.H.B., A.M.E.-H., M.K.M.A. and M.F.; resources, N.I.M.H., M.K.M.A., M.H.B., A.M.E.-H. and M.F.; data curation, N.I.M.H., M.H.B., A.M.E.-H. and M.F.; writing—original draft preparation, N.I.M.H., M.H.B., M.K.M.A., A.M.E.-H. and M.F.; writing—review and editing, A.A.-S.; visualization, N.I.M.H., M.H.B., M.K.M.A. and M.F.; supervision, M.H.B., M.K.M.A. and M.F.; project administration, M.H.B., M.K.M.A. and M.F.; funding acquisition, N.I.M.H. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Desert Research Center, Egypt. 21/12/2022.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- González-Curbelo, M.Á.; Kabak, B. Occurrence of mycotoxins in dried fruits worldwide, with a focus on aflatoxins and ochratoxin A: A Review. Toxins 2023, 15, 576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mukhtar, K.; Nabi, B.G.; Ansar, S.; Bhat, Z.F.; Aadil, R.M.; Mousavi Khaneghah, A. Mycotoxins and consumers awareness: Recent progress and future challenges. Toxicon 2023, 232, 107227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akinde, S.B.; Olaitan, J.O.; Ajayi, E.I.; Adeniyi, M.A. Fungal quality and molecular characterization of aflatoxin-producing Aspergillus species in irrigation water and fresh vegetables in southwest Nigeria. Jordan J. Agri. Sci. 2018, 14, 1. [Google Scholar]

- McCormick, S.P. Microbial Detoxification of Mycotoxins. J. Chem. Ecol. 2013, 39, 907–918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, J. Current understanding on aflatoxin biosynthesis and future perspective in reducing aflatoxin contamination. Toxins 2012, 4, 1024–1057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azzoune, N.; Mokrane, S.; Riba, A.; Bouras, N.; Verheecke, C.; Sabaou, N.; Mathieu, F. Contamination of common spices by aflatoxigenic fungi and aflatoxin B1 in Algeria. Qual. Assur. Saf. Crops Foods 2016, 8, 137–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agriopoulou, S.; Stamatelopoulou, E.; Varzakas, T. Advances in occurrence, importance and mycotoxin control strategies: Prevention and detoxification in foods. Foods 2020, 9, 137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, R.; Ghazali, F.M.; Mahyudin, N.A.; Samsudin, N.P. Morphological characterization and determination of aflatoxigenic and non-aflatoxigenic Aspergillus flavus isolated from sweet corn kernels and soil in Malaysia. Agriculture 2020, 10, 450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birck, N.M.M.; Lorini, I.; Scussel, V.M. Fungus and mycotoxins in wheat grain at post-harvest. In Proceedings of the 9th International Working Conference on Stored Product Protection, Campinas, Brazil, 15–18 October 2006; pp. 198–205. [Google Scholar]

- Sangare, L.; Zhao, Y.; Folly, Y.; Chang, J.; Li, J.; Selvaraj, J.; Xing, F.; Zhou, L.; Wang, Y.; Liu, Y. Aflatoxin B1 Degradation by a Pseudomonas Strain. Toxins 2014, 6, 3028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adebo, O.A.; Njobeh, P.B.; Mavumengwana, V. Degradation and detoxification of AFB 1 by Staphylocococcus warneri, Sporosarcina sp. and Lysinibacillus fusiformis. Food Cont. 2016, 68, 92–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alshannaq, A.; Yu, J.H. Occurrence, toxicity and analysis of major mycotoxins in food. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2017, 14, 632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van der Merwe, K.J.; Steyn, P.S.; Fourie, L.; Scott, D.B.; Theron, J.J. Ochratoxin A, a toxic metabolite produced by Aspergillus ochraceus Wilh. Nature 1965, 205, 1112–1113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben Miri, Y.; Benabdallah, A.; Chentir, I.; Djenane, D.; Luvisi, A.; De Bellis, L. Comprehensive insights into ochratoxin A: Occurrence, analysis and control strategies. Foods 2024, 13, 1184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jonatova, P.; Dzuman, Z.; Prusova, N.; Hajslova, J.; Stranska-Zachariasova, M. Occurrence of ochratoxin A and its stereoisomeric degradation product in various types of coffee available in the Czech market. World Mycotoxin J. 2020, 13, 97–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, L.J.G.; Teixeira, A.C.; Pereira, A.M.P.T.; Pena, A.; Lino, C.M. Ochratoxin A in beers marketed in portugal: Occurrence and human risk assessment. Toxins 2020, 12, 249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torović, L.; Lakatoš, I.; Majkić, T.; Beara, I. Risk to public health related to the presence of ochratoxin A in wines from Fruška Gora. LWT 2020, 129, 109537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carballo, D.; Fernández-Franzón, M.; Ferrer, E.; Pallarés, N.; Berrada, H. Dietary exposure to mycotoxins through alcoholic and non-alcoholic beverages in Valencia, Spain. Toxins 2021, 13, 438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikolchina, I.; Rodrigues, P. A Preliminary study on microbiota and ochratoxin a contamination in commercial palm dates (Phoenix dactylifera). Mycotoxin Res. 2021, 37, 215–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Celik, D.; Kabak, B. Assessment to propose a maximum permitted level for ochratoxin A in dried figs. J. Food Compos. Anal. 2022, 112, 104705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delfino, D.; Lucchetti, D.; Mauti, T.; Mancuso, M.; Di Giustino, P.; Triolone, D.; Vaccari, S.; Bonanni, R.C.; Neri, B.; Russo, K. Investigation of ochratoxin A in commercial cheeses and pork meat products by liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry. J. Food Sci. 2022, 87, 4465–4475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wafula, E.N.; Muhonja, C.N.; Kuja, J.O.; Owaga, E.E.; Makonde, H.M.; Mathara, J.M.; Kimani, V.W. Lactic acid bacteria from African fermented cereal-based products: Potential biological control agents for mycotoxins in Kenya. J. Toxicol. 2022, 2397767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chang, P.K.; Hua, S.S. Non aflatoxigenic Aspergillus flavus TX9-8 competitively prevents aflatoxin accumulation by A. flavus isolates of large and small sclerotial morphotypes. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2007, 114, 275–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hormisch, D.; Hormisch, D.; Brost, I.; Kohring, G.W.; Giffhorn, F.; Kroppenstedt, R.M.; Stackebradt, E.; Färber, P.; Holzapfel, W.H. Mycobacterium fluoranthenivorans sp. nov.; a fluoranthene and aflatoxin B1 degrading bacterium from contaminated soil of a former coal gas plant. Syst. Appl. Microbiol. 2004, 27, 653–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alberts, J.F.; Engelbrecht, Y.; Steyn, P.S.; Holzapfel, W.H.; van Zyl, W.H. Biological degradation of aflatoxin B1 by Rhodococcus erythropolis cultures. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2006, 109, 121–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samuel, M.S.; Sivaramakrishna, A.; Mehta, A. Degradation and detoxification of aflatoxin B1 by Pseudomonas putida. Int. Biodeter. Biodegr. 2014, 86, 202–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harkai, P.; Szabó, I.; Cserháti, M.; Krifaton, C.; Risa, A.; Radó, J.; Balázs, A.; Berta, K.; Kriszt, B. Biodegradation of aflatoxin-B1 and zearalenone by Streptomyces sp. collection. Int. Biodeter. Biodegr. 2016, 108, 48–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prettl, Z.; Dési, E.; Lepossa, A.; Kriszt, B.; Kukolya, J.; Nagy, E. Biological degradation of aflatoxin B1 by a Rhodococcus pyridinivorans strain in by-product of bioethanol. Anim. Feed Sci. Technol. 2017, 224, 104–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adebo, O.A.; Njobeh, P.B.; Sidu, S.; Adebiyi, J.A.; Mavumengwana, V. Aflatoxin B1 degradation by culture and lysate of a Pontibacter sp. Food Cont. 2017, 80, 99–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afsah-Hejri, L. Saprophytic yeasts: Effective biocontrol agents against Aspergillus flavus. Int. Food Res. J. 2013, 20, 3403–3409. [Google Scholar]

- Xia, X.; Zhang, Y.; Li, M.; Garba, B.; Zhang, Q.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, H.; Li, P. Isolation and characterization of a Bacillus subtilis strain with aflatoxin B1 biodegradation capability. Food Cont. 2017, 75, 92–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raksha, R.K.; Vipin, A.V.; Hariprasad, P.; Anu Appaiah, K.A.; Venkateswaran, G. Biological detoxification of Aflatoxin B1 by Bacillus licheniformis CFR1. Food Cont. 2017, 71, 234–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meneely, J.P.; Kolawole, O.; Haughey, S.A.; Sarah, J.; Miller, S.J.; Rudolf Krska, R.; Christopher, T.; Elliott, C.T. The challenge of global aflatoxins legislation with a focus on peanuts and peanut products: A systematic review. Expo. Health 2023, 15, 467–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Shi, H.; Heng, J.; Wang, D.; Bian, K. Antimicrobial, plant growth-promoting and genomic properties of the peanut endophyte Bacillus velezensis LDO2. Microbiol. Res. 2019, 218, 41–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, H.; Carvalhais, L.C.; Crawford, M.; Singh, E.; Dennis, P.G.; Pieterse, C.M.J.; Schenk, P.M. Inner plant values: Diversity, colonization and benefits from endophytic bacteria. Front. Microbiol. 2017, 8, 2552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ren, X.; Zhang, Q.; Zhang, W.; Mao, J.; Li, P. Control of aflatoxigenic molds by antagonistic microorganisms: Inhibitory behaviors, bioactive compounds, related mechanisms, and influencing factors. Toxins 2020, 12, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carter, M.R.; Gregorich, E.G. Soil Sampling and Methods of Analysis; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2007; Available online: https://www.aweimagazine.com (accessed on 1 January 2023).

- Corry, J.E.L.; Curtis, G.D.W.; Baird, R.M. Handbook of culture media for food microbiology. Progress in Industrial Microbiology, 3rd ed.; Elsevier Sci. B.V.: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2003; Volume 37, ISBN 0-444-51084-2. [Google Scholar]

- Hoque, J.; Shamsi, S. Study of fungi associated with some selected vegetables of Dhaka City. Bangladesh J. Sci. Res. 2011, 24, 181–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zrari, T.J.O. Detection of aflatoxin from some Aspergillus sp. isolated from wheat seeds. J. Life Sci. 2013, 7, 1041–1047. [Google Scholar]

- Davis, N.D.; Iyer, S.K.; Diener, U.L. Improved method of screening for aflatoxin with a coconut agar medium. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 1987, 53, 1593–1595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, X.Q.; Holbrook, C.C.; Lynch, R.C.; Guo, B.Z. β-1,3-Glucanase activity in peanut seeds (Arachis hypogaea) is induced by inoculation with Aspergillus flavus and Copuriflies with a conglutun-like protein. Amer. Phytopathol. Soc. 2005, 95, 5–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, L.; Duan, C.; Zhao, Y.; Gao, L.; Niu, C.; Xu, J.; Li, S. Reduction of aflatoxin B 1 toxicity by Lactobacillus plantarum C88: A potential probiotic strain isolated from Chinese traditional fermented food “tofu”. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0170109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohale, S.; Magan, N.; Medina, A. Comparison of growth, nutritional utilization patterns and niche overlap indices of toxigenic and atoxigenic Aspergillus flavus strains. Fungal Biol. 2013, 117, 650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- AOAC. Official Methods of Analysis, 20th ed.; AOAC International: Gaithersburg, MD, USA, 2016; Chapter 49; no. 991.31. [Google Scholar]