Data-Driven AI Modeling of Renewable Energy-Based Smart EV Charging Stations Using Historical Weather and Load Data

Abstract

1. Introduction

Novelty and Contribution

- Multi-Source Long-Term Data: This study incorporates more than 10 years of actual weather and load data of various operation conditions, as compared to most previous studies that used short-term or synthetic datasets, which could only adequately serve a limited range of different conditions.

- Urban-Centric SEVCS Forecasting: The approach is specifically designed for urban high-density settings, in which the challenge of renewable variability and load volatility is a special concern of the SEVCS implementation.

- Clear and Well-Defined Workflow: The entire data source becomes publicly available, and the research workflow (data acquisition to training) is reproducible in MATLAB, facilitating research transparency.

- AI Methods Benchmarking: Comparing the Neural Fitting and Regression Learner models, the research provides a justifiable reference point to AI-based prediction of the renewable-based EV charging systems.

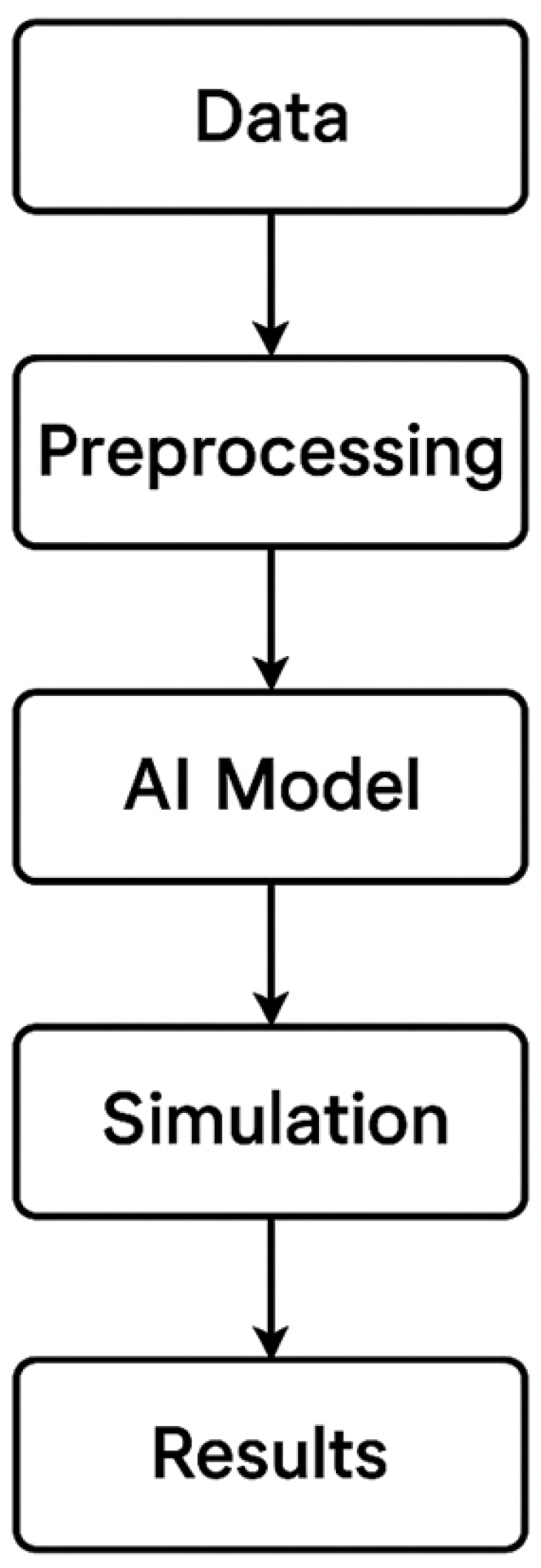

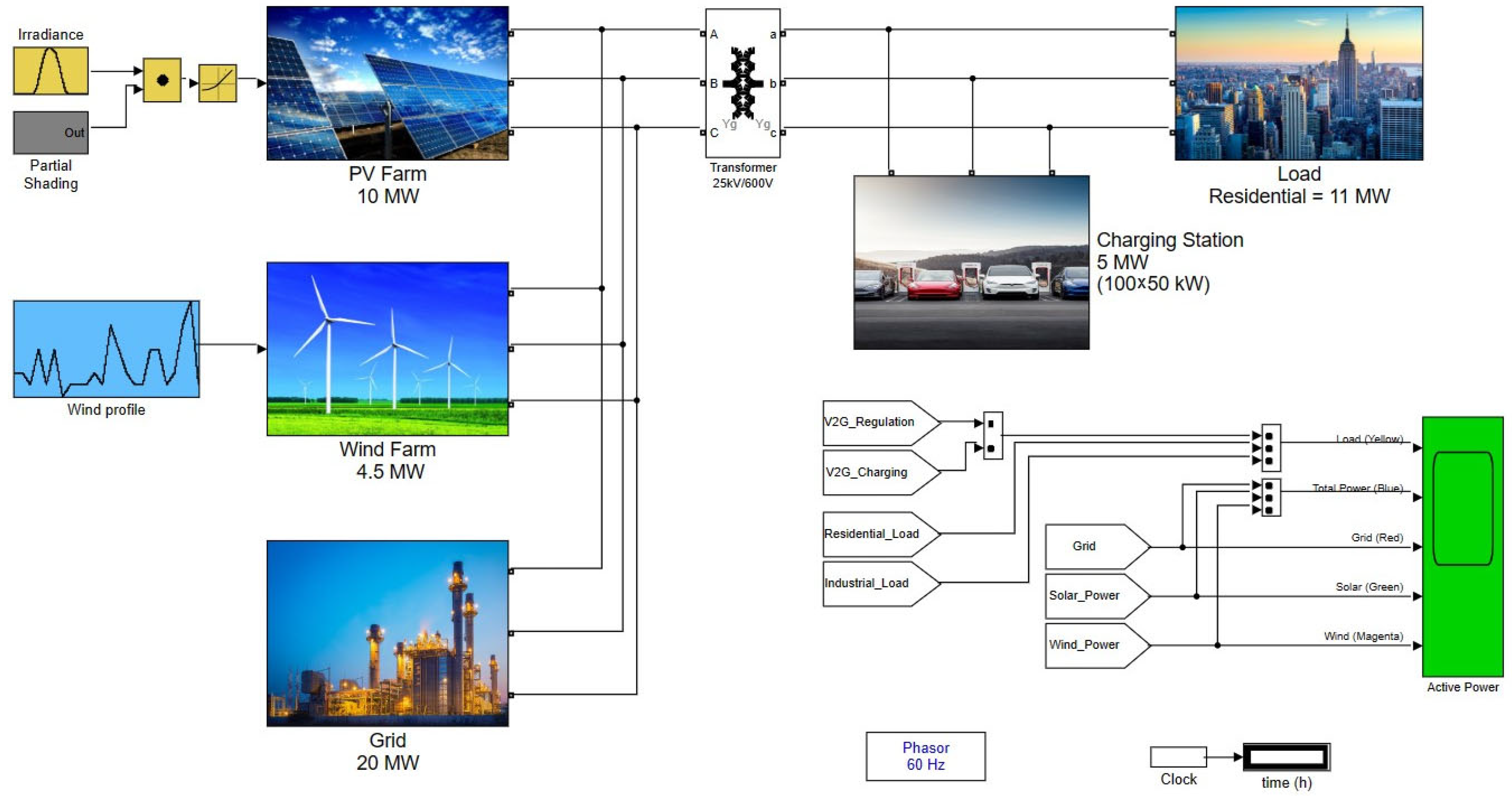

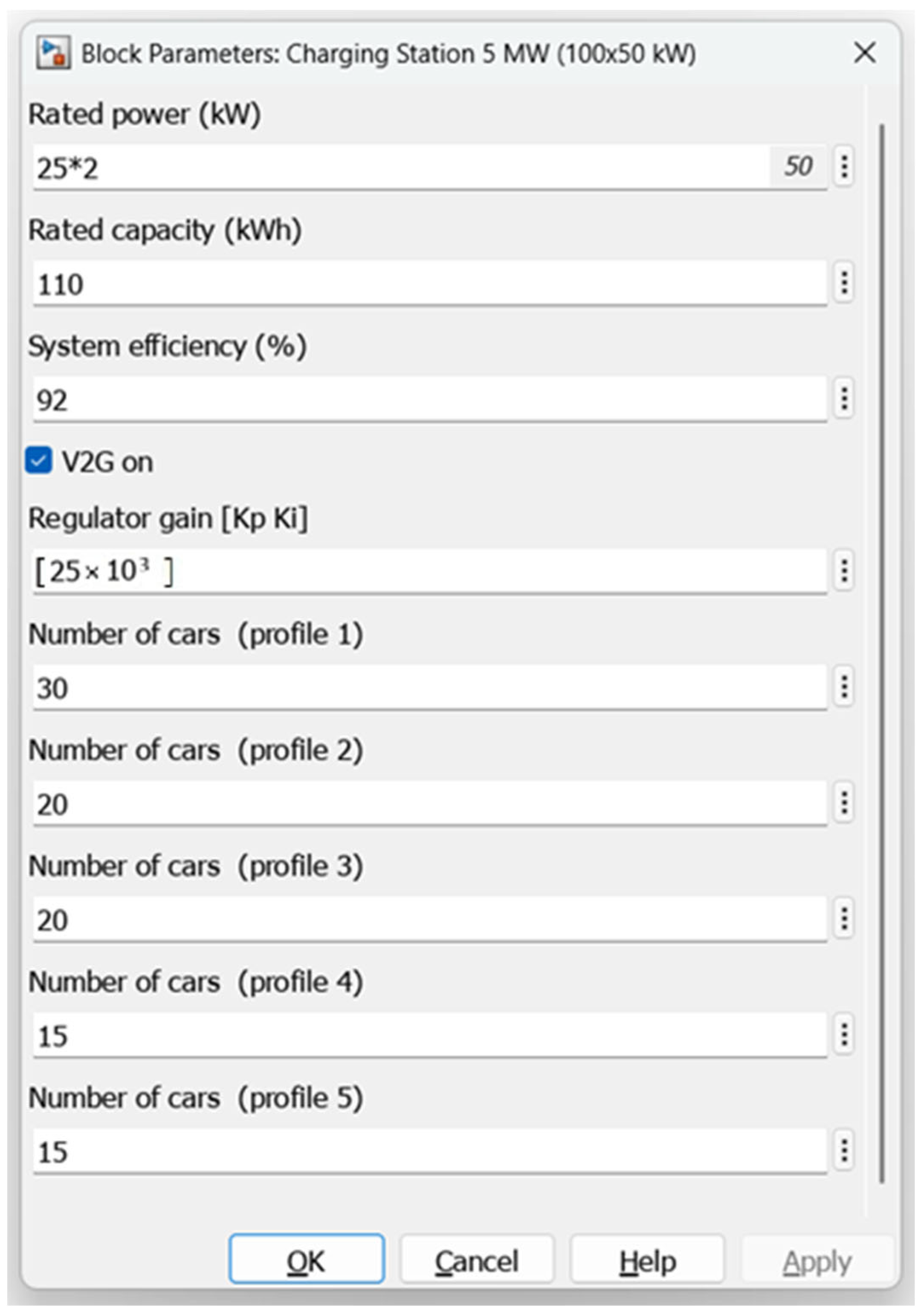

2. Materials and Methods

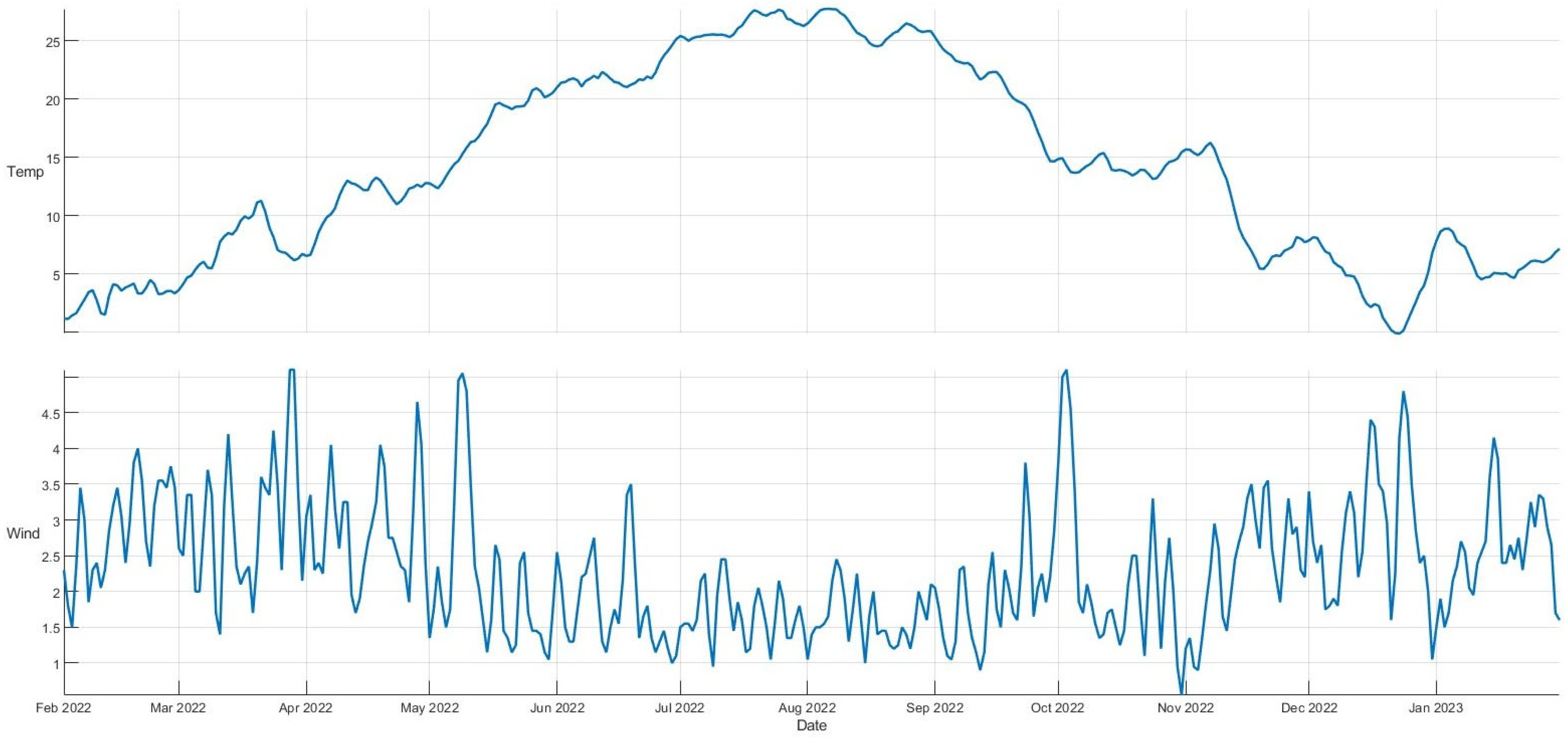

2.1. Data Sources and Provenance

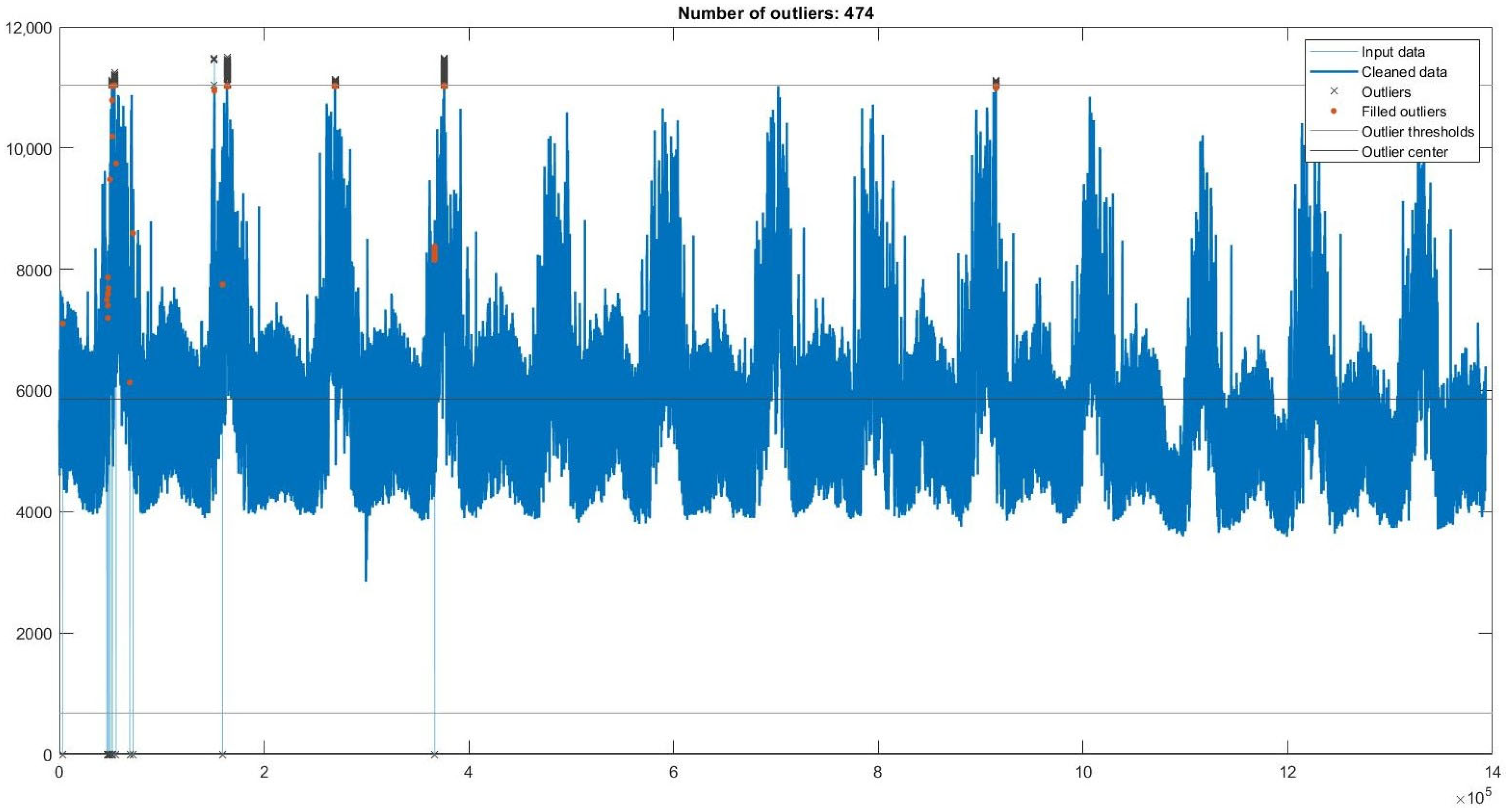

2.2. Preprocessing and Feature Engineering Data

- Missing Data Handling: The missing values are spotted and then replaced with linear interpolation to maintain time continuity.

- Outlier Detection and Correction: The value of 3.5 was taken as the threshold to identify outliers, and the outliers were replaced with linear interpolations to ensure the integrity of underlying trends.

- Smoothing: To eliminate the variation in random values, a moving average filter with a smoothing factor of 0.3 was used to avoid eliminating long-term fluctuations.

- Time Synchronization: The load data and the weather data were resampled to a common time step of 30 min, which made the records synchronized.

- Construction of Features: New predictor features were constructed, such as hour of day, week of the day, month of the year, year, and a binary variable indicating weekend, which improved the behavioral and temporal coverage of the dataset.

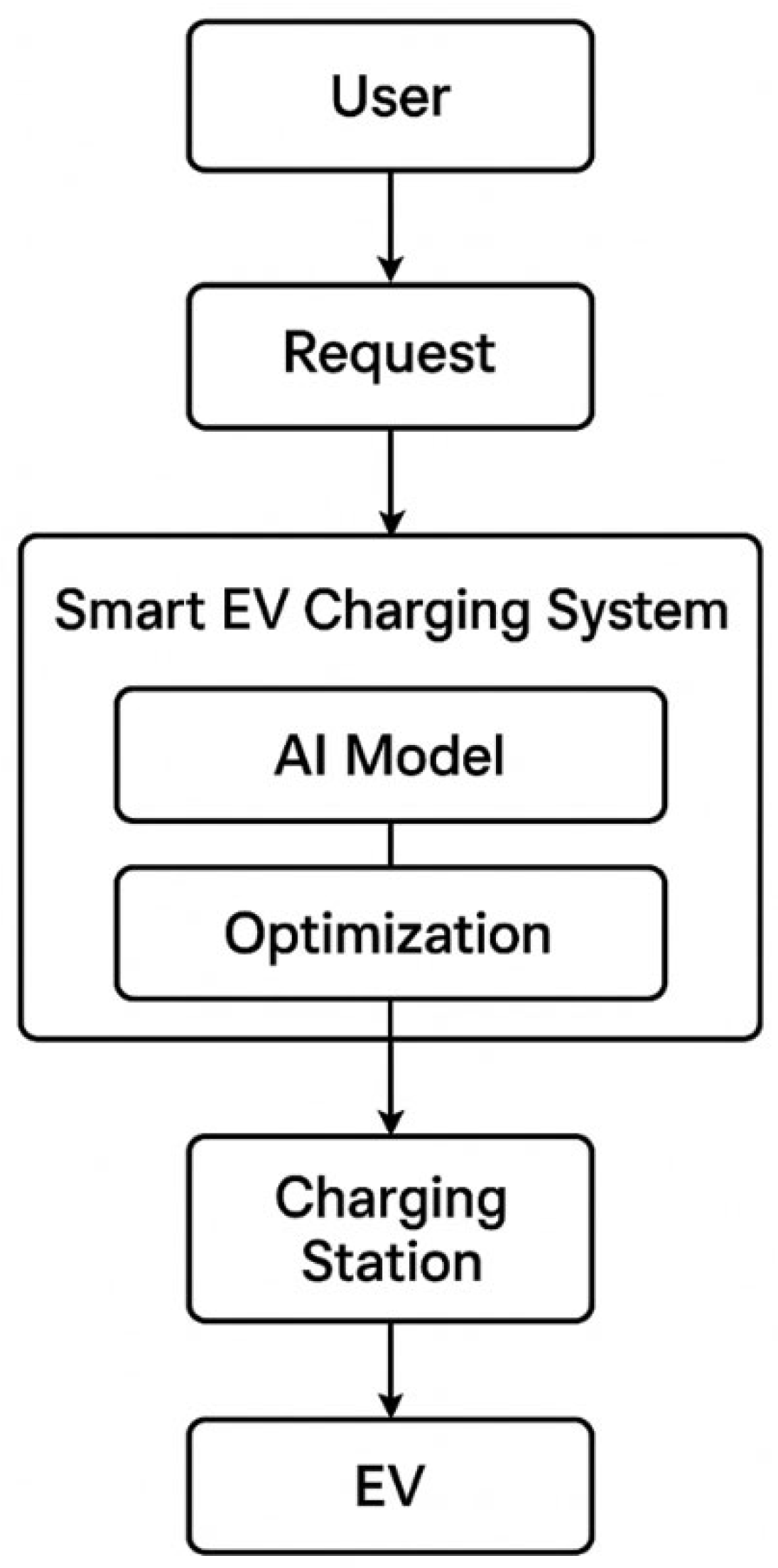

2.3. AI Model Development

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Model Performance and Comparative Analysis

3.2. Analysis of Error Sources and Model Behavior

3.3. Implications for Renewable-Based Smart EV Charging Stations

- Prioritize charging during periods of renewable energy surplus.

- Reduce dependency on fossil-fuel-based backup generators.

- Prevent transformer overloading and peak-hour congestion.

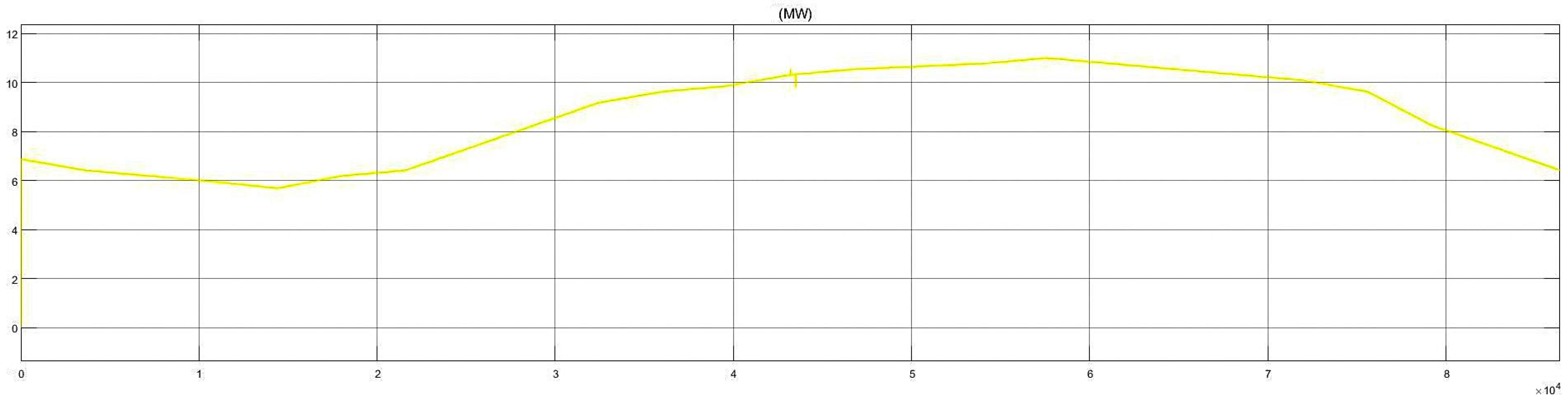

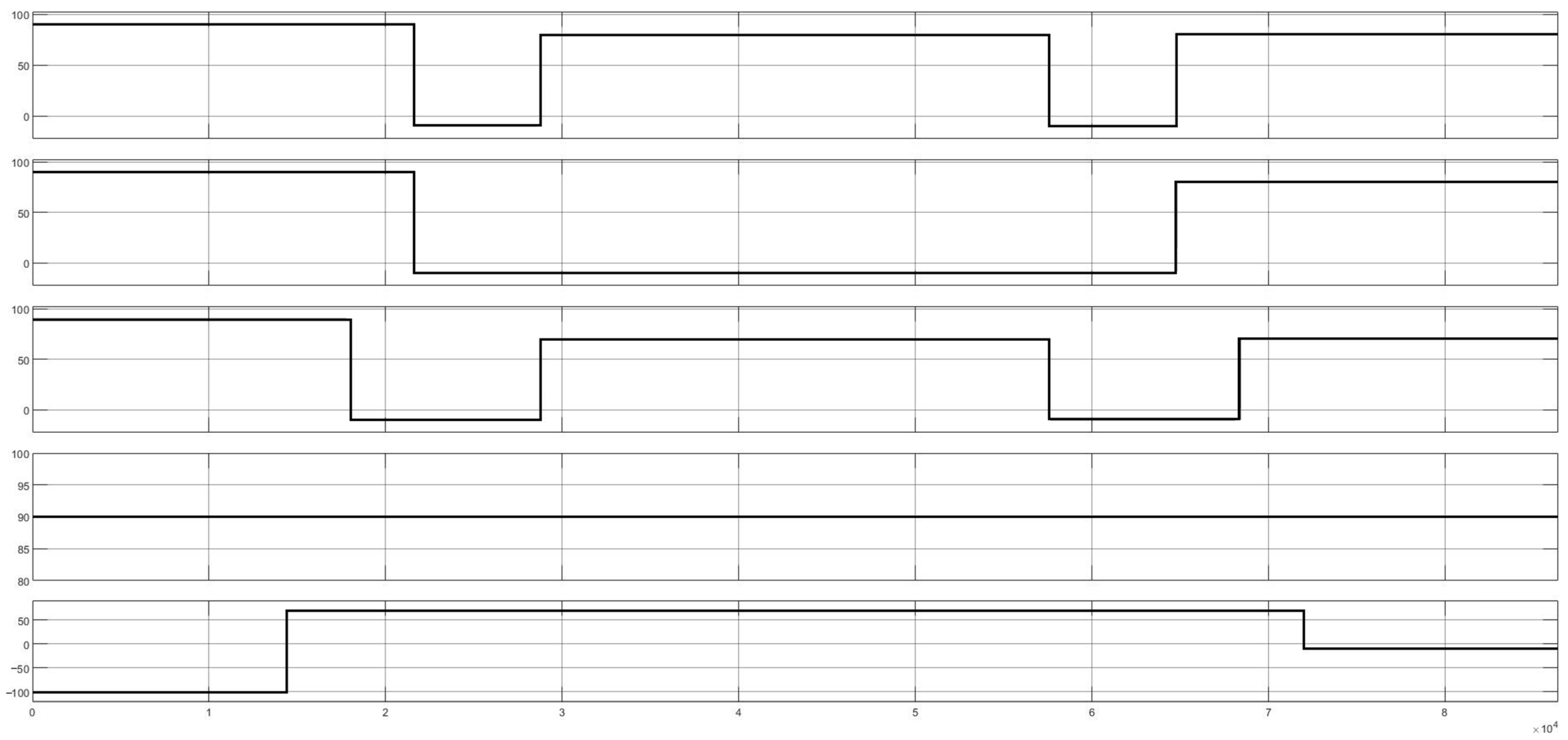

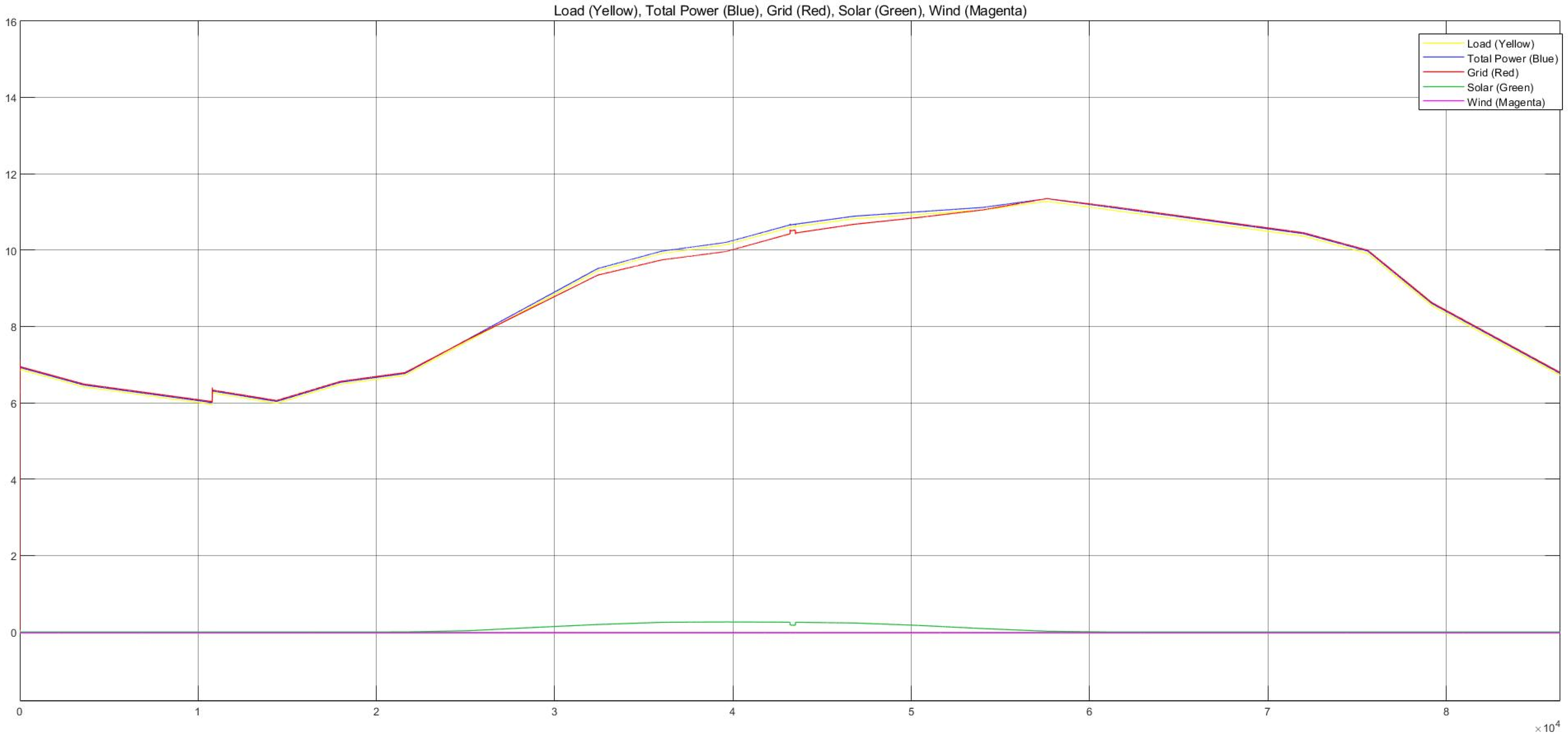

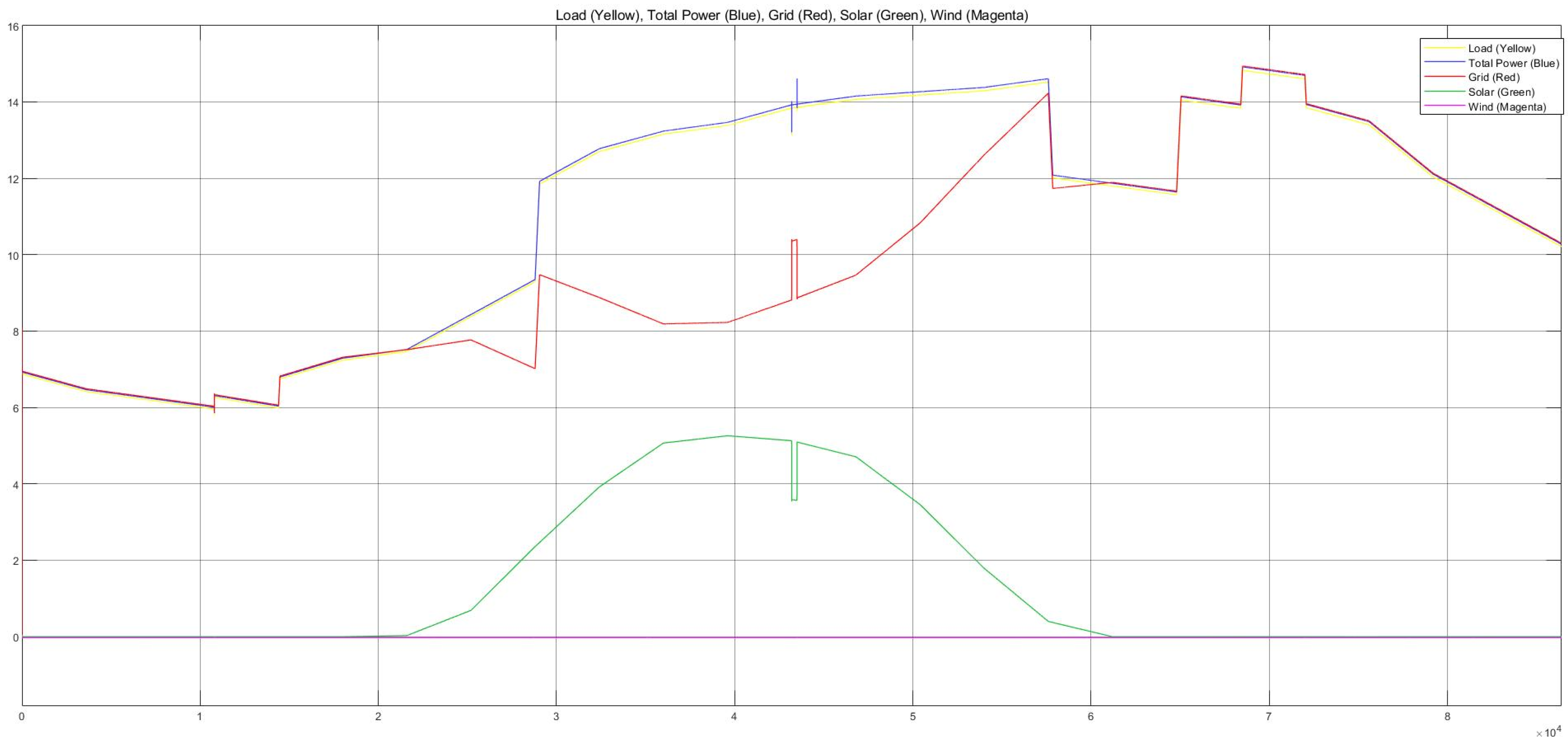

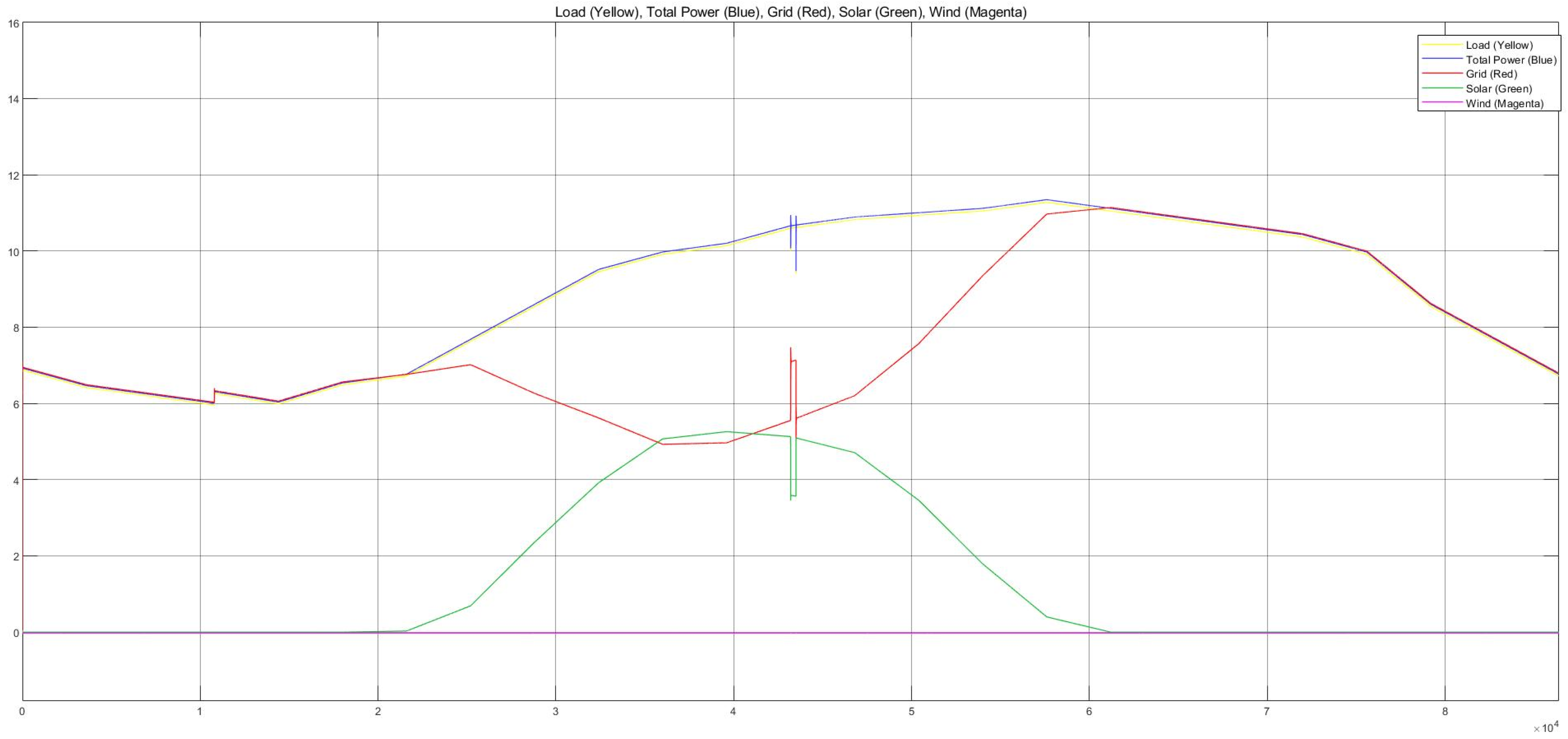

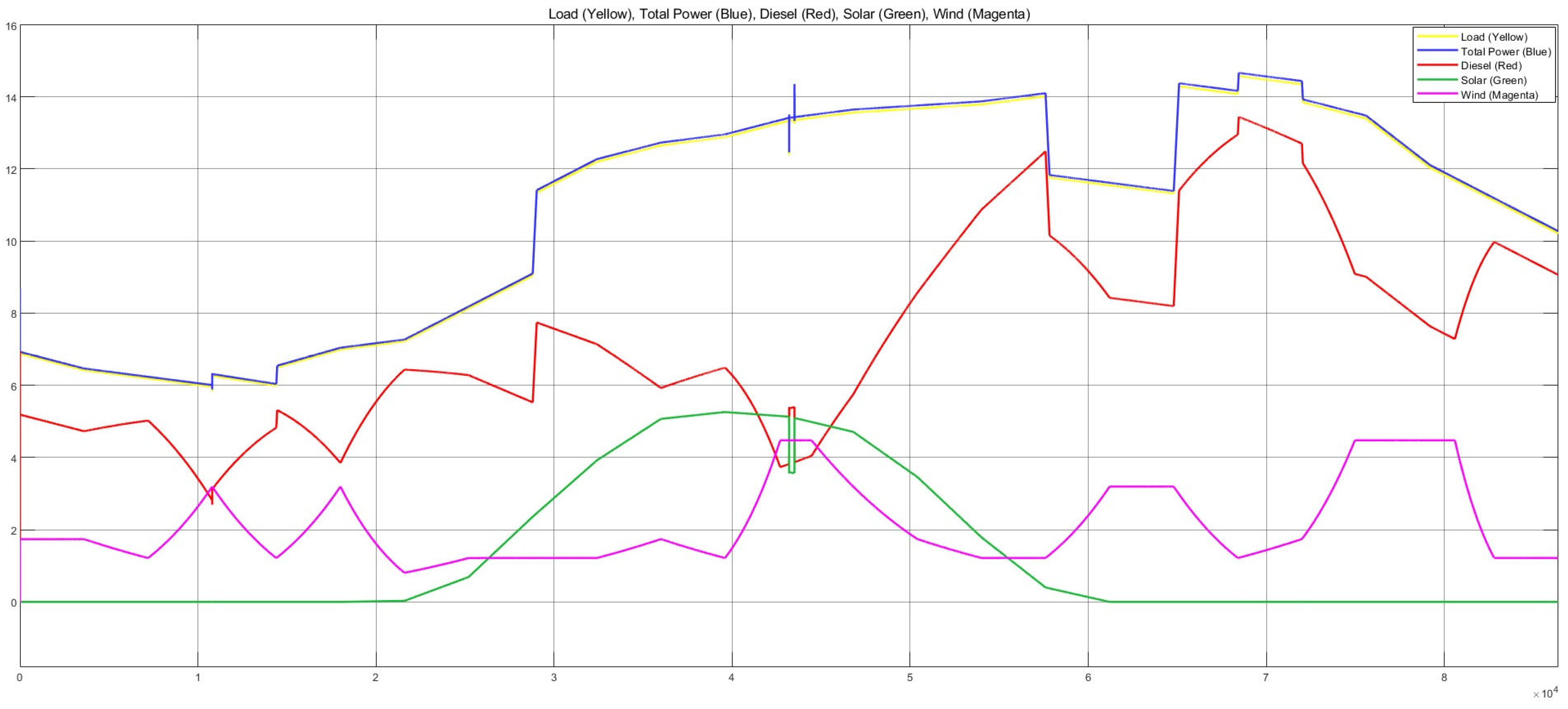

3.4. Analysis of Simulation and System Behavior

3.5. Comparison and Related Studies

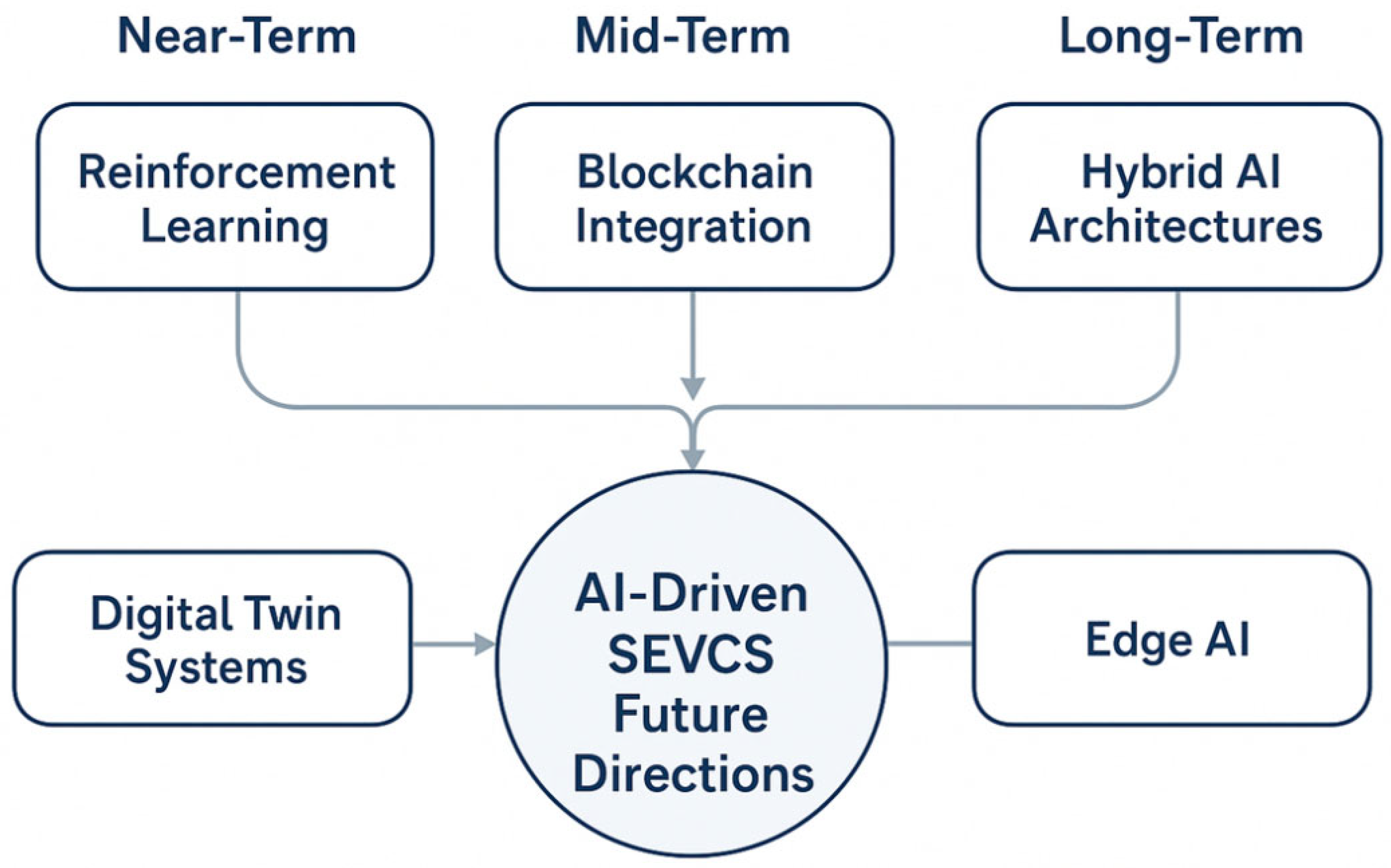

3.6. Limitations and Future Improvements

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AI | Artificial intelligence |

| CO2 | Carbon Dioxide |

| CSP | Concentrating Solar-Thermal Power |

| DC | Direct Current |

| EV | Electric vehicle |

| G2V | Grid to Vehicle |

| GW | Gigawatt |

| kW | Kilowatt |

| MW | Megawatt |

| PV | Photovoltaic |

| REBSCS | Renewable Energy-Based Smart Charging Station |

| SEVCS | Smart Electric Vehicle Charging Station |

| TOU | Time of Use |

| V2G | Vehicle to Grid |

References

- Chien, F.; Hsu, C.-C.; Ozturk, I.; Sharif, A.; Sadiq, M. The role of renewable energy and urbanization towards greenhouse gas emission in top Asian countries: Evidence from advance panel estimations. Renew. Energy 2022, 186, 207–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.; Shao, M.; Zheng, C.; Ji, H.; Gao, X.; Wang, Q. Air pollutant emissions from fossil fuel consumption in China: Current status and future predictions. Atmos. Environ. 2020, 231, 117536. [Google Scholar]

- Abbasi, K.R.; Shahbaz, M.; Zhang, J.; Irfan, M.; Alvarado, R. Analyze the environmental sustainability factors of China: The role of fossil fuel energy and renewable energy. Renew. Energy 2022, 187, 390–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voumik, L.C.; Islam, A.; Ray, S.; Yusop, N.Y.M.; Ridzuan, A.R. CO2 emissions from renewable and non-renewable electricity generation sources in the G7 countries: Static and dynamic panel assessment. Energies 2023, 16, 1044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zafar, M.W.; Shahbaz, M.; Sinha, A.; Sengupta, T.; Qin, Q. How renewable energy consumption contribute to environmental quality? The role of education in OECD countries. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 268, 122149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olabi, A.G.; Mahmoud, M.; Soudan, B.; Wilberforce, T.; Ramadan, M. Geothermal based hybrid energy systems, toward eco-friendly energy approaches. Renew. Energy 2020, 147, 2003–2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.; Khan, Z.A.; Alvarez-Alvarado, M.S.; Zhang, Y.; Huang, Z.; Imran, M. A critical review of sustainable energy policies for the promotion of renewable energy sources. Sustainability 2020, 12, 5078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gozgor, G.; Mahalik, M.K.; Demir, E.; Padhan, H. The impact of economic globalization on renewable energy in the OECD countries. Energy Policy 2020, 139, 111365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanwal, S.; Mehran, M.T.; Hassan, M.; Anwar, M.; Naqvi, S.R.; Khoja, A.H. An integrated future approach for the energy security of Pakistan: Replacement of fossil fuels with syngas for better environment and socio-economic development. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2022, 156, 111978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vinuesa, R.; Azizpour, H.; Leite, I.; Balaam, M.; Dignum, V.; Domisch, S.; Felländer, A.; Langhans, S.D.; Tegmark, M.; Nerini, F.F. The role of artificial intelligence in achieving the Sustainable Development Goals. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koch, N. Greening oil money: The geopolitics of energy finance going green. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2022, 93, 102833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, D.; Lv, M.; Yang, J.; Yi, W. Optimizing the locations and sizes of solar assisted electric vehicle charging stations in an urban area. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 112772–112782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheng, M.S.; Sreenivasan, A.V.; Sharp, B.; Du, B. Well-to-wheel analysis of greenhouse gas emissions and energy consumption for electric vehicles: A comparative study in Oceania. Energy Policy 2021, 158, 112552. [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, Y.; He, X.; Wang, H.; Wang, M.; Zhang, S.; Ma, D.; Wang, B.; Wu, Y. Well-to-wheels greenhouse gas and air pollutant emissions from battery electric vehicles in China. Mitig. Adapt. Strateg. Glob. Change 2020, 25, 355–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharifi, P.; Banerjee, A.; Feizollahi, M.J. Leveraging owners’ flexibility in smart charge/discharge scheduling of electric vehicles to support renewable energy integration. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2020, 149, 106762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, H.; Jing, P.; Wang, B.; Cai, Y.; Ye, J.; Wang, B. The effect of record-high gasoline prices on the consumers’ new energy vehicle purchase intention: Evidence from the uniform experimental design. Energy Policy 2023, 175, 113500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, L.V.; Carrel, A.L.; Shi, W.; Sintov, N.D. Why are charging stations associated with electric vehicle adoption? Untangling effects in three United States metropolitan areas. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2022, 89, 102663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chawla, U.; Mohnot, R.; Mishra, V.; Singh, H.V.; Singh, A.K. Factors Influencing Customer Preference and Adoption of Electric Vehicles in India: A Journey towards More Sustainable Transportation. Sustainability 2023, 15, 7020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharyya, S.S.; Thakre, S. Exploring the factors influencing electric vehicle adoption: An empirical investigation in the emerging economy context of India. Foresight 2021, 23, 311–326. [Google Scholar]

- Luo, T.; Song, Y.; Li, G. An agent-based simulation study for escaping the “chicken-egg” dilemma between electric vehicle penetration and charging infrastructure deployment. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2023, 194, 106966. [Google Scholar]

- Shi, L.; Hao, Y.; Lv, S.; Cipcigan, L.; Liang, J. A comprehensive charging network planning scheme for promoting EV charging infrastructure considering the Chicken-Eggs dilemma. Res. Transp. Econ. 2021, 88, 100837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thananusak, T.; Punnakitikashem, P.; Tanthasith, S.; Kongarchapatara, B. The development of electric vehicle charging stations in Thailand: Policies, players, and key issues (2015–2020). World Electr. Veh. J. 2020, 12, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiwari, D. Application of Artificial Intelligence in Three Phase Unbalanced Smart Power Distribution Grid. Ph.D. Thesis, West Virginia University, Morgantown, WV, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmad, T.; Zhang, D.; Huang, C.; Zhang, H.; Dai, N.; Song, Y.; Chen, H. Artificial intelligence in sustainable energy industry: Status Quo, challenges and opportunities. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 289, 125834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nozari, H.; Szmelter-Jarosz, A.; Ghahremani-Nahr, J. Analysis of the Challenges of Artificial Intelligence of Things (AIoT) for the Smart Supply Chain (Case Study: FMCG Industries). Sensors 2022, 22, 2931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bauer, G.S.; Zheng, C.; Shaheen, S.; Kammen, D.M. Leveraging Big Data and Coordinated Charging for Effective Taxi Fleet Electrification: The 100% EV Conversion of Shenzhen, China. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2021, 23, 10343–10353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abid, M.; Tabaa, M.; Chakir, A.; Hachimi, H. Routing and charging of electric vehicles: Literature review. Energy Rep. 2022, 8, 556–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ElHusseini, H.; Assi, C.; Moussa, B.; Attallah, R.; Ghrayeb, A. Blockchain, AI and smart grids: The three musketeers to a decentralized EV charging infrastructure. IEEE Internet Things Mag. 2020, 3, 24–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adak, D.; Bhattacharyya, R.; Barshilia, H.C. A state-of-the-art review on the multifunctional self-cleaning nanostructured coatings for PV panels, CSP mirrors and related solar devices. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2022, 159, 112145. [Google Scholar]

- Virtanen, E.; Lappalainen, J.; Nurmi, M.; Viitasalo, M.; Tikanmäki, M.; Heinonen, J.; Atlaskin, E.; Kallasvuo, M.; Tikkanen, H.; Moilanen, A. Balancing profitability of energy production, societal impacts and biodiversity in offshore wind farm design. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2022, 158, 112087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivera, S.; Kouro, S.; Vazquez, S.; Goetz, S.M.; Lizana, R.; Romero-Cadaval, E. Electric vehicle charging infrastructure: From grid to battery. IEEE Ind. Electron. Mag. 2021, 15, 37–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thangavel, S.; Mohanraj, D.; Girijaprasanna, T.; Raju, S.; Dhanamjayulu, C.; Muyeen, S.M. A Comprehensive Review on Electric Vehicle: Battery Management System, Charging Station, Traction Motors. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 20994–21019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Powar, V.; Singh, R. End-to-End Direct-Current-Based Extreme Fast Electric Vehicle Charging Infrastructure Using Lithium-Ion Battery Storage. Batteries 2023, 9, 169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, A.; Shah, K.; Shah, C.; Shah, M. State of charge, remaining useful life and knee point estimation based on artificial intelligence and machine learning in lithium-ion EV batteries: A comprehensive review. Renew. Energy Focus 2022, 42, 146–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dabbaghjamanesh, M.; Moeini, A.; Kavousi-Fard, A. Reinforcement learning-based load forecasting of electric vehicle charging station using Q-learning technique. IEEE Trans. Ind. Inform. 2020, 17, 4229–4237. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed, M.; Zheng, Y.; Amine, A.; Fathiannasab, H.; Chen, Z. The role of artificial intelligence in the mass adoption of electric vehicles. Joule 2021, 5, 2296–2322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, J.; Yang, J.; Li, Y.; Wang, H.; Ji, H.; Yang, W.; Wang, K. Load forecasting of electric vehicle charging station based on grey theory and neural network. Energy Rep. 2021, 7, 487–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, F.; Iqbal, A.; Ashraf, I.; Marzband, M.; Khan, I. Optimal location of electric vehicle charging station and its impact on distribution network: A review. Energy Rep. 2022, 8, 2314–2333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, H.S.; Rahman, M.M.; Li, S.; Tan, C.W. Electric vehicles standards, charging infrastructure, and impact on grid integration: A technological review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2020, 120, 109618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gharbaoui, M.; Valcarenghi, L.; Brunoi, R.; Martini, B.; Conti, M.; Castoldi, P. An advanced smart management system for electric vehicle recharge. In Proceedings of the 2012 IEEE International Electric Vehicle Conference, Greenville, SC, USA, 4–8 March 2012; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2012; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Fernandes, F.; Morais, H.; Vale, Z.; Ramos, C. Dynamic load management in a smart home to participate in demand response events. Energy Build. 2014, 82, 592–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Brey, B. Smart Solar Charging: Bi-Directional AC Charging (V2G) in the Netherlands. J. Energy Power Eng. 2017, 11, 483–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kungl, G. The Incumbent German Power Companies in a Changing Environment: A Comparison of E. ON, RWE, EnBW and Vattenfall from 1998 to 2013; Universität Stuttgart, Institut für Sozialwissenschaften, Abteilung für Organisations- und Innovationssoziologie, Stuttgart: Stuttgart, Germany, 2014. [Google Scholar]

| Data Type | Source | Temporal Resolution | Period Covered | Variables |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Load Data | NYISO Open Data Portal | 30 min | 2010–2023 | Total City Load (MW) |

| Weather Data | NOAA NCEI | 30 min | 2010–2023 | Temperature (°C), Wind Speed (m/s) |

| Model | RMSE (MW) | MAE (MW) | MAPE (%) | R2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Linear Regression | 42.6 | 35.2 | 6.3 | 0.89 |

| Neural Fitting (Proposed) | 36.4 | 28.8 | 4.9 | 0.93 |

| Persistence Baseline (Yesterday’s Load) | 45.8 | 38.4 | 7.5 | 0.86 |

| Hour | Load (MW) | Total Power (MW) | Grid (MW) | Solar (MW) | Wind (MW) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C | Not-C | C | Not-C | C | Not-C | C | Not-C | C | Not-C | |

| 1 | 6.4 | 6.4 | 6.4 | 6.4 | 4.7 | 4.7 | 0 | 0 | 1.7 | 1.7 |

| 2 | 6.2 | 6.2 | 6.2 | 6.2 | 5 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 1.2 | 1.2 |

| 3 | 6.3 | 6.3 | 6.3 | 6.3 | 3.1 | 3.1 | 0 | 0 | 3.2 | 3.2 |

| 4 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 4.8 | 4.8 | 0 | 0 | 1.2 | 1.2 |

| 5 | 7.3 | 6.5 | 7.3 | 6.5 | 4.1 | 3.3 | 0 | 0 | 3.2 | 3.2 |

| 6 | 7.5 | 6.8 | 7.5 | 6.8 | 6.7 | 6 | 0 | 0 | 0.8 | 0.8 |

| 7 | 8.4 | 7.7 | 8.4 | 7.7 | 6.5 | 5.8 | 0.7 | 0.7 | 1.2 | 1.2 |

| 8 | 9.3 | 8.6 | 9.3 | 8.6 | 5.8 | 5.1 | 2.3 | 2.3 | 1.2 | 1.2 |

| 9 | 12.8 | 9.5 | 12.8 | 9.5 | 7.6 | 4.3 | 3.9 | 3.9 | 1.3 | 1.3 |

| 10 | 13.2 | 9.9 | 13.2 | 9.9 | 6.4 | 3.2 | 5 | 5 | 1.7 | 1.7 |

| 11 | 13.4 | 10.2 | 13.4 | 10.2 | 7 | 3.7 | 5.3 | 5.3 | 1.2 | 1.2 |

| 12 | 13.9 | 10.6 | 13.9 | 10.6 | 4.2 | 1.9 | 5.1 | 5.1 | 4.6 | 4.6 |

| 13 | 14.1 | 10.8 | 14.1 | 10.8 | 6.2 | 3 | 4.7 | 4.7 | 3.1 | 3.1 |

| 14 | 14.2 | 11 | 14.2 | 11 | 9 | 5.8 | 3.5 | 3.5 | 1.7 | 1.7 |

| 15 | 14.3 | 11.1 | 14.3 | 11.1 | 11.3 | 8.1 | 1.8 | 1.8 | 1.2 | 1.2 |

| 16 | 14.5 | 11.3 | 14.5 | 11.3 | 12.9 | 9.7 | 0.4 | 0.4 | 1.2 | 1.2 |

| 17 | 11.8 | 11 | 11.8 | 11 | 8.7 | 7.8 | 0 | 0 | 3.2 | 3.2 |

| 18 | 11.6 | 10.8 | 11.6 | 10.8 | 8.4 | 7.6 | 0 | 0 | 3.2 | 3.2 |

| 19 | 13.8 | 10.6 | 13.8 | 10.6 | 12.7 | 9.4 | 0 | 0 | 1.2 | 1.2 |

| 20 | 14.6 | 10.3 | 14.6 | 10.3 | 12.9 | 8.6 | 0 | 0 | 1.7 | 1.7 |

| 21 | 13.4 | 9.9 | 13.4 | 9.9 | 9 | 5.4 | 0 | 0 | 4.5 | 4.5 |

| 22 | 12 | 8.5 | 12 | 8.5 | 7.6 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 4.5 | 4.5 |

| 23 | 11.1 | 7.6 | 11.1 | 7.6 | 9.9 | 6.4 | 0 | 0 | 1.2 | 1.2 |

| 24 | 10.2 | 6.7 | 10.2 | 6.7 | 9 | 5.5 | 0 | 0 | 1.2 | 1.2 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Published by MDPI on behalf of the World Electric Vehicle Association. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Sajjad, H.B.; Malik, F.H.; Abid, M.I.; Khan, M.O.; Haider, Z.M.; Arshad, M.J. Data-Driven AI Modeling of Renewable Energy-Based Smart EV Charging Stations Using Historical Weather and Load Data. World Electr. Veh. J. 2026, 17, 37. https://doi.org/10.3390/wevj17010037

Sajjad HB, Malik FH, Abid MI, Khan MO, Haider ZM, Arshad MJ. Data-Driven AI Modeling of Renewable Energy-Based Smart EV Charging Stations Using Historical Weather and Load Data. World Electric Vehicle Journal. 2026; 17(1):37. https://doi.org/10.3390/wevj17010037

Chicago/Turabian StyleSajjad, Hamza Bin, Farhan Hameed Malik, Muhammad Irfan Abid, Muhammad Omer Khan, Zunaib Maqsood Haider, and Muhammad Junaid Arshad. 2026. "Data-Driven AI Modeling of Renewable Energy-Based Smart EV Charging Stations Using Historical Weather and Load Data" World Electric Vehicle Journal 17, no. 1: 37. https://doi.org/10.3390/wevj17010037

APA StyleSajjad, H. B., Malik, F. H., Abid, M. I., Khan, M. O., Haider, Z. M., & Arshad, M. J. (2026). Data-Driven AI Modeling of Renewable Energy-Based Smart EV Charging Stations Using Historical Weather and Load Data. World Electric Vehicle Journal, 17(1), 37. https://doi.org/10.3390/wevj17010037