Energy Harvesting Devices for Extending the Lifespan of Lithium-Polymer Batteries: Insights for Electric Vehicles

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Related Works

1.2. Research Context

- Research and development to improve energy harvesting efficiency. Innovations such as triboelectric nanogenerators and hybrid systems improve power output by utilizing multiple energy sources. For instance, Khan et al. [21] developed a solar optimizer based on maximum power point tracking (MPPT), while Liao et al. [22] explored cellulose-based harvesters. Mondal et al. [23] and Sevcik et al. [24] reviewed hybrid devices and energy transducer technologies. Further research focuses on the advancement of thermal and solar harvesting techniques [25,26,27,28].

- Hybrid systems for IoT and wearable devices. Various studies investigate the integration of energy harvesting in IoT systems and wearable devices to reduce the need for battery replacement and optimize energy use [29,30]. Abdulmalek et al. [31] developed a hybrid wearable healthcare system for real-time monitoring. Nishanth and Senthilkumar [3] proposed using solar or piezoelectric harvesters to extend the battery life of the fitness tracker. Ali et al. [32] reviewed wearable energy harvesting methods, focusing on the heat and motion of the human body, and examined various technologies, including piezoelectric, triboelectric, thermoelectric, and hybrid systems.

- Electric and hybrid vehicles. In recent years, several studies have examined how best to utilize the energy of electric and hybrid vehicles. Particularly, Prasad et al. [33] introduced a method that integrates an optimization algorithm with a neural architecture to determine the optimal energy distribution. In addition, Manivannan [34] applied machine learning to create a smart energy management system for hybrid electric vehicles. To enhance its performance, an IoT-based smart charging system was implemented to schedule vehicle-to-grid connections. Finally, Shen [35] studied the trends in IoT-based charging stations for electric vehicles and their roles in smart energy dispatch, load balancing, remote monitoring, and the integration of renewable energy. Furthermore, the study highlighted the primary challenges of scaling and implementing IoT-based systems, including cost ineffectiveness, interoperability issues, and security concerns.

- Advanced energy storage and harvesting systems. Portable energy storage and harvesting systems are vital for daily use, especially in healthcare and wearable technology. Traditional batteries tend to be bulky, but advances in materials have allowed for flexible, lightweight alternatives. These integrated systems support continuous operation and reduce dependency on external power. Zhang et al. [36] reviewed technologies such as solar cells, biofuel cells, nanogenerators, super-capacitors, and various batteries, analyzing energy density, power, and durability. To address the mismatch between intermittent energy harvesting and constant power needs, advanced storage solutions such as super-capacitors are being explored [37,38,39,40,41]. Their fast charge/discharge capabilities and long cycle life make them a promising option for hybrid systems [42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49].

- Smart energy management systems. Hybrid systems are based on smart circuits to efficiently manage the energy of both harvesters and batteries [50,51,52]. These systems dynamically balance power sources to ensure a stable supply and maximize the use of harvested energy [53,54,55,56]. In this sense, Yaseen et al. [57] developed a framework for resilient IoT systems using dynamic energy management and sustainable harvesting methods.

1.3. Contribution

- Experimental data link driving profiles to the battery SoC in an electric vehicle. It supports safe and efficient operation, helps estimate battery life through charge-discharge cycles, and enables discharge curve analysis to assess the available energy.

- Test findings on the application of wind energy harvesters as supplementary power sources in small EVs are presented. These results help estimate the potential improvement in the SoC and lifespan of the battery.

- A detailed assessment is conducted to quantify efficiency losses and estimate the net energy contribution of the energy harvesters. This assessment is based on the technical specifications of the Savonius-rotor microturbine.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Considerations

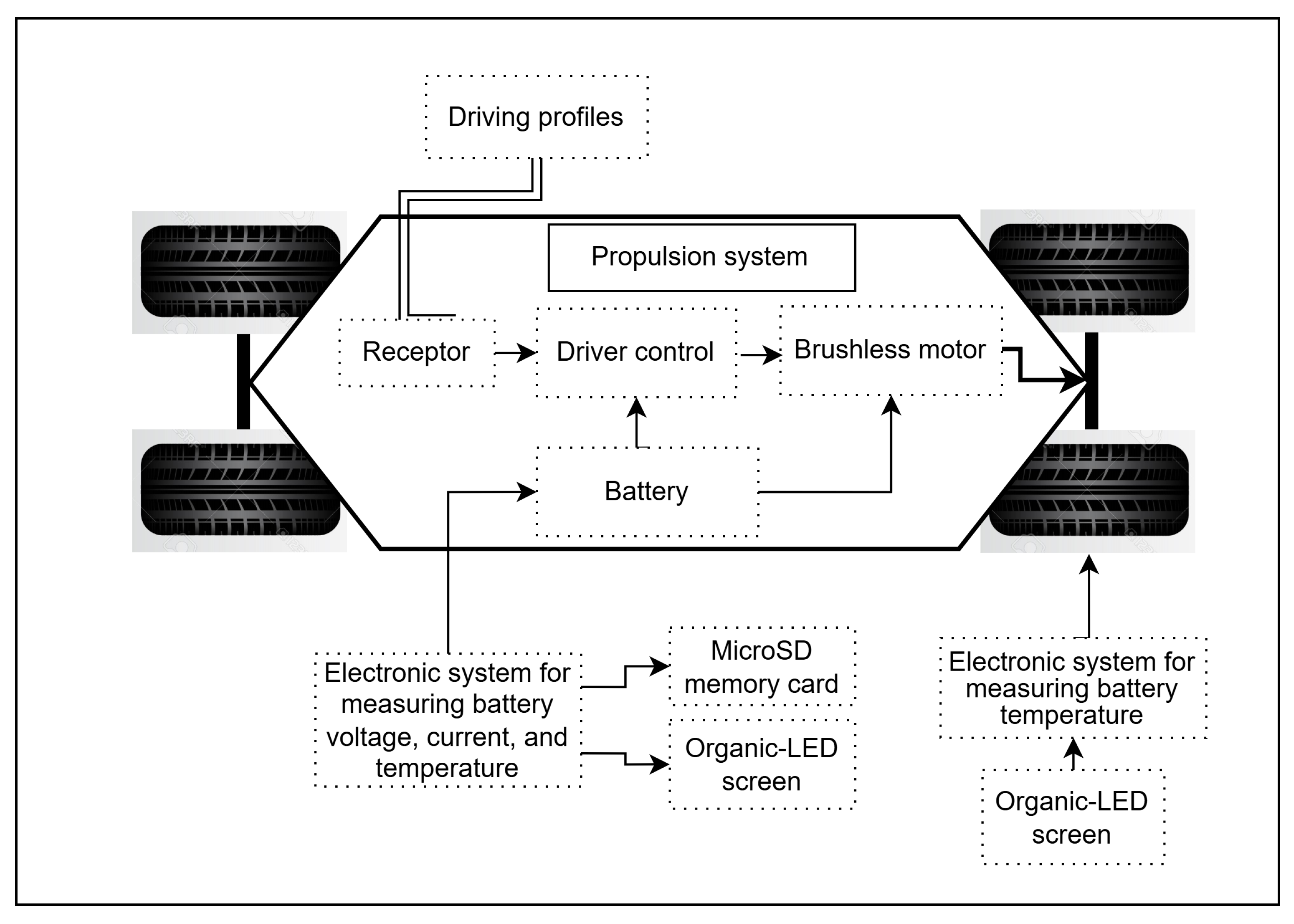

2.2. Method Description

- Fully charge the vehicle battery to its nominal capacity.

- Connect the electric vehicle to the docking platform, ensuring a secure coupling.

- Select a driving profile and start the electric vehicle to begin the experimental procedure.

- Acquire the voltage, current, and temperature of the vehicle battery.

- Save the data to the microSD memory card, enabling subsequent review via the organic LED screen integrated within the electronic system.

- Estimate the battery SoC using the Coulomb counting method as defined by Equation (1)where represents the initial battery SoC at full capacity (100%), is the instantaneous battery current, and denotes the nominal battery capacity.

- Terminate the experiment once the battery voltage, , approaches the predefined cut-off voltage, .

- Compute the instantaneous power consumption as .

- Ascertain the power output () of a single energy harvester using the manufacturer specifications or design-based calculations, accounting for the efficiencies of both the power source and conversion circuitry.

- Determine the minimum number of energy harvesting circuits () required to sustain continuous system operation, ensuring that the aggregated power output meets or exceeds the system’s average energy demand, formally expressed as:Note that if = 0, then N = 0, since there is no energy available for harvesting. Therefore, should be estimated according to Equation (3) when > 0.where indicates that the number should be rounded up to the next whole number, as using only a fraction of an energy harvesting circuit is not feasible.

2.3. Case Study

2.4. Experimental Conditions and Settings

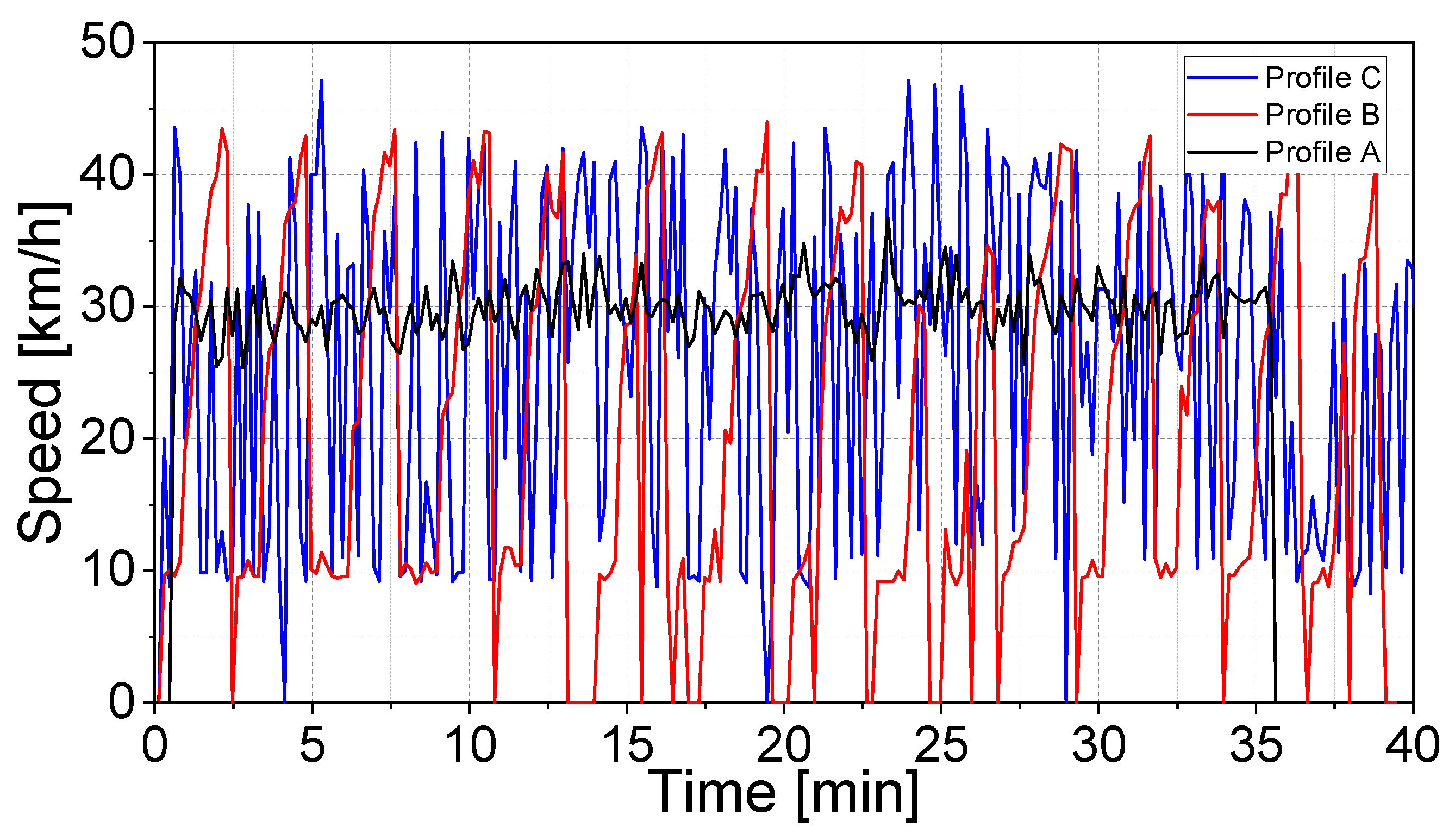

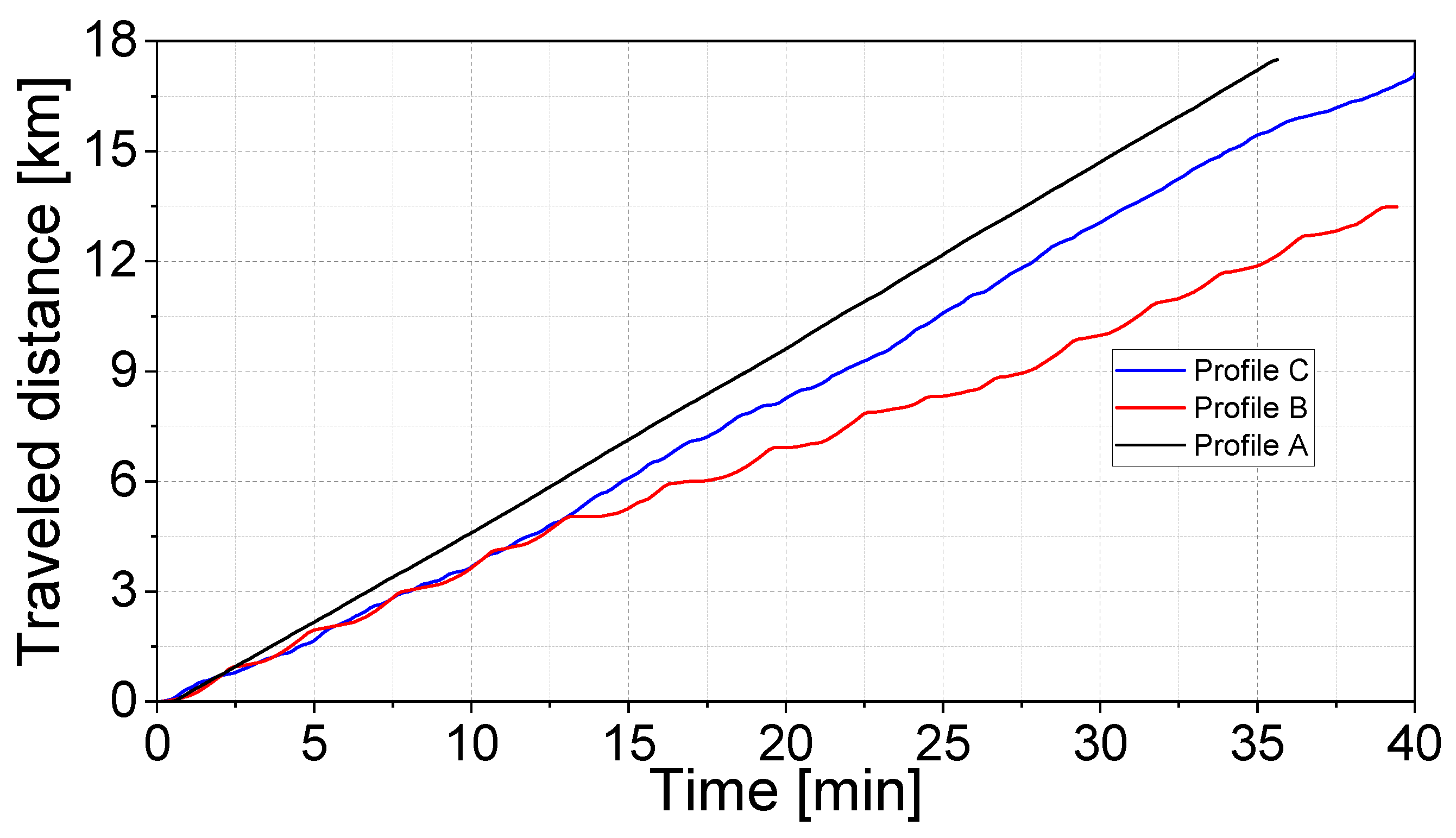

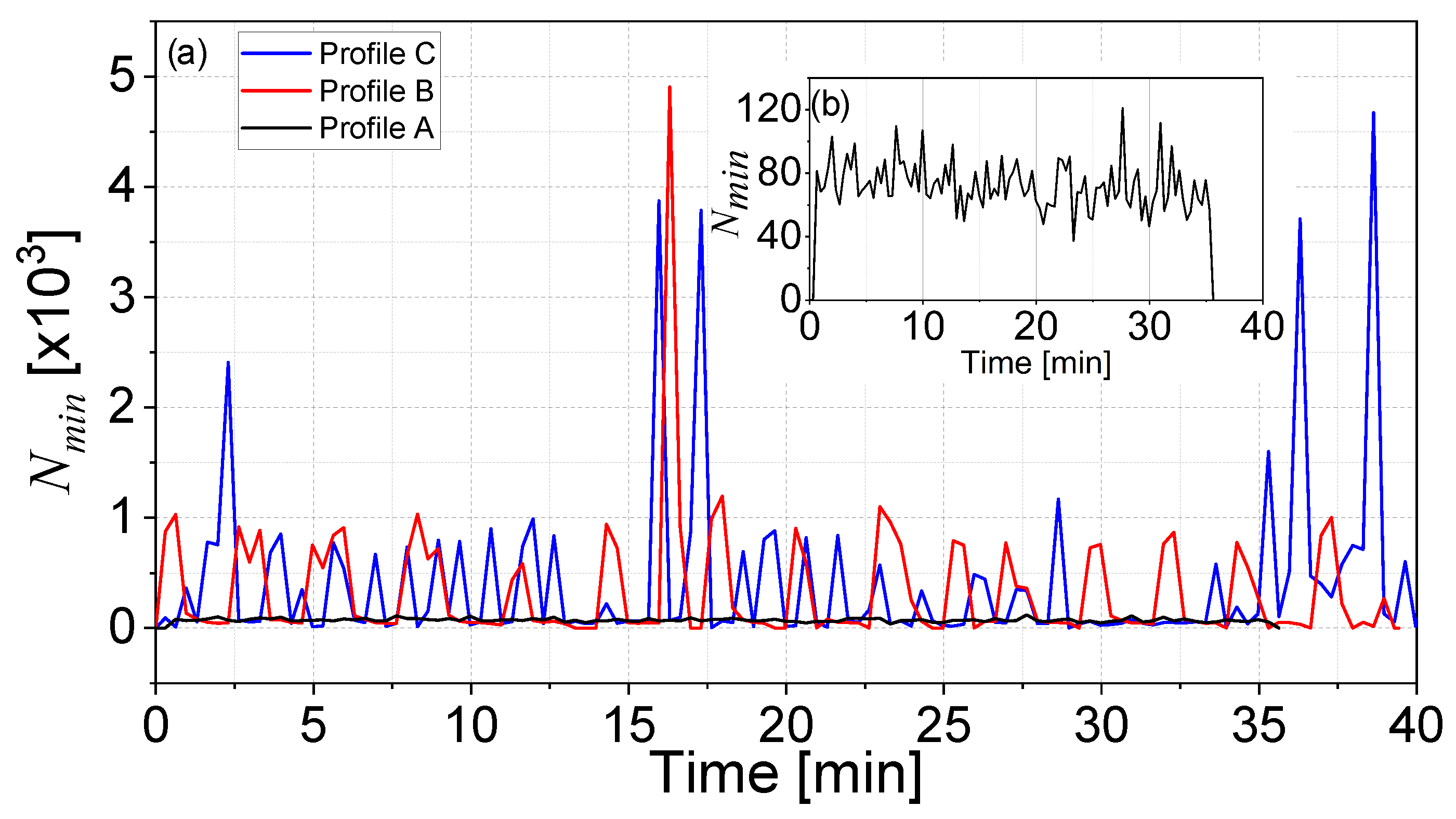

- Profile A. It is characterized by a constant speed of approximately 30 km/h.

- Profile B. It features a variable speed according to a sawtooth signal.

- Profile C. It entails a driving profile with randomly varying speeds.

3. Results

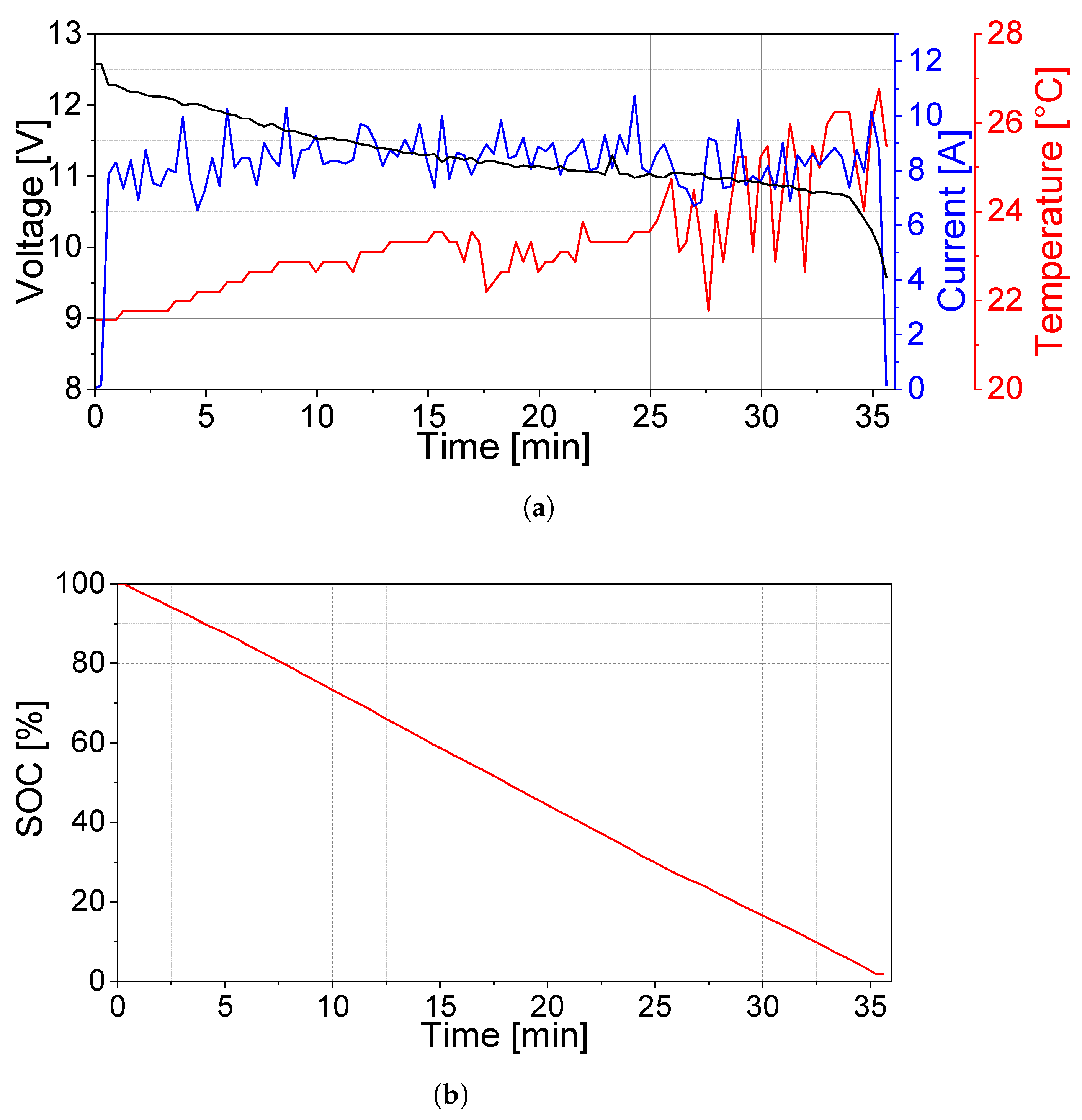

3.1. Experiment Based on Driving Profile A

3.2. Experiment Based on Driving Profile B

3.3. Experiment Based on Driving Profile C

3.4. Integration of Wind Energy Harvesters into the Li-Po Battery System

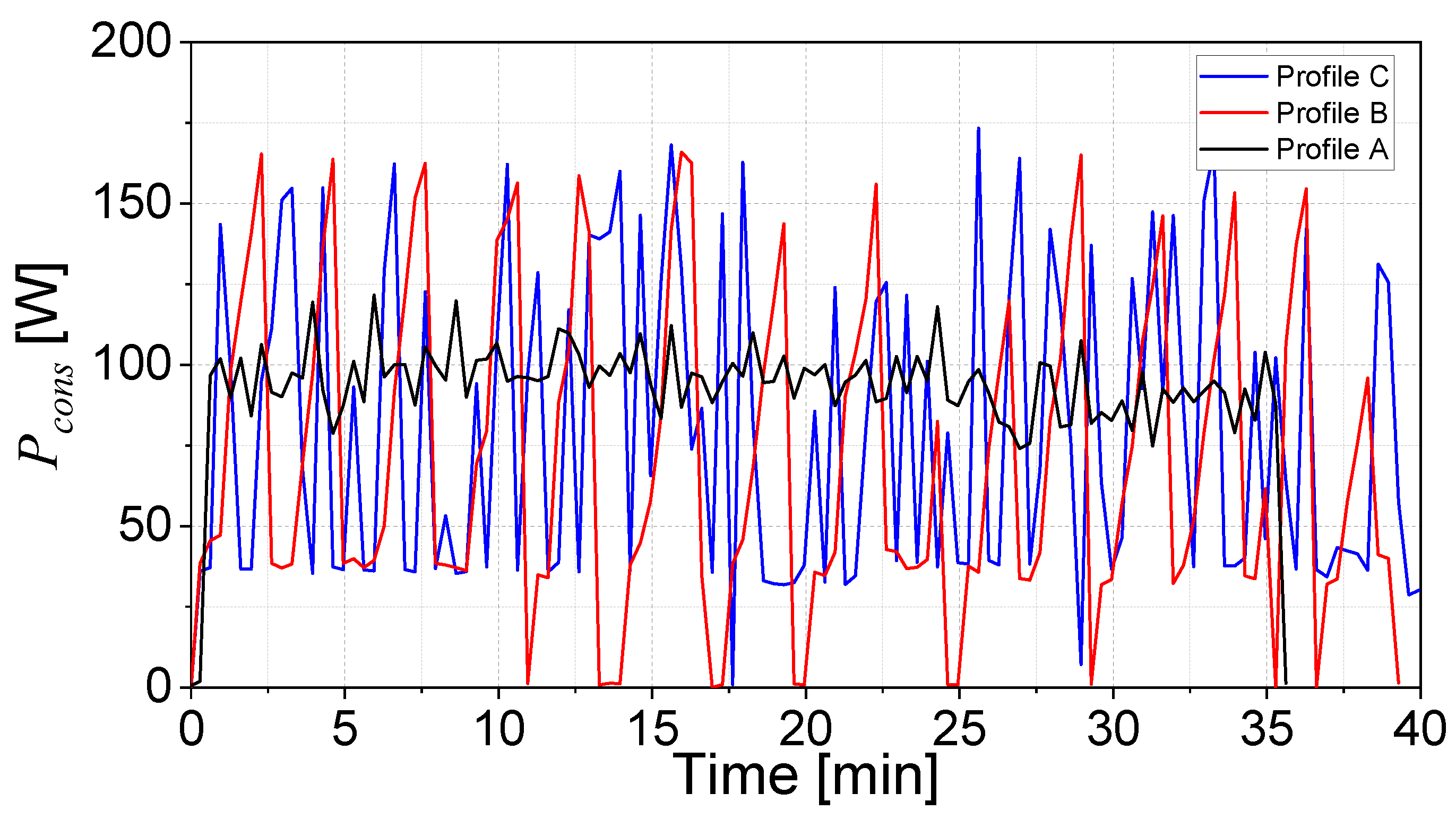

- Estimation of . Figure 9 shows the instantaneous power consumption of the 1:10 scale electric vehicle under each driving profile. The black, red, and blue lines represent profiles A, B, and C, respectively. Instantaneous consumed power, = was calculated from the voltage and current of the battery over time.

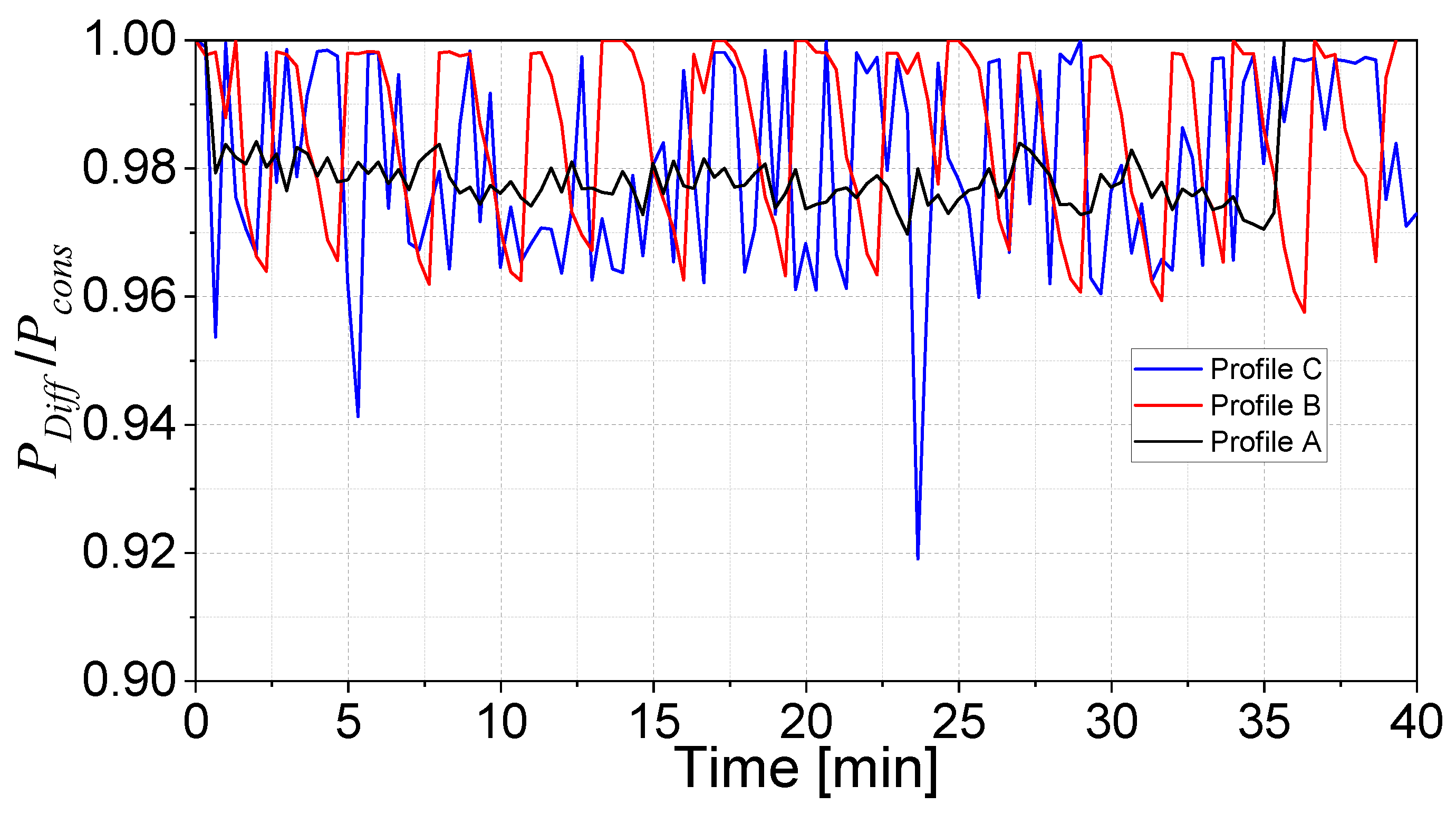

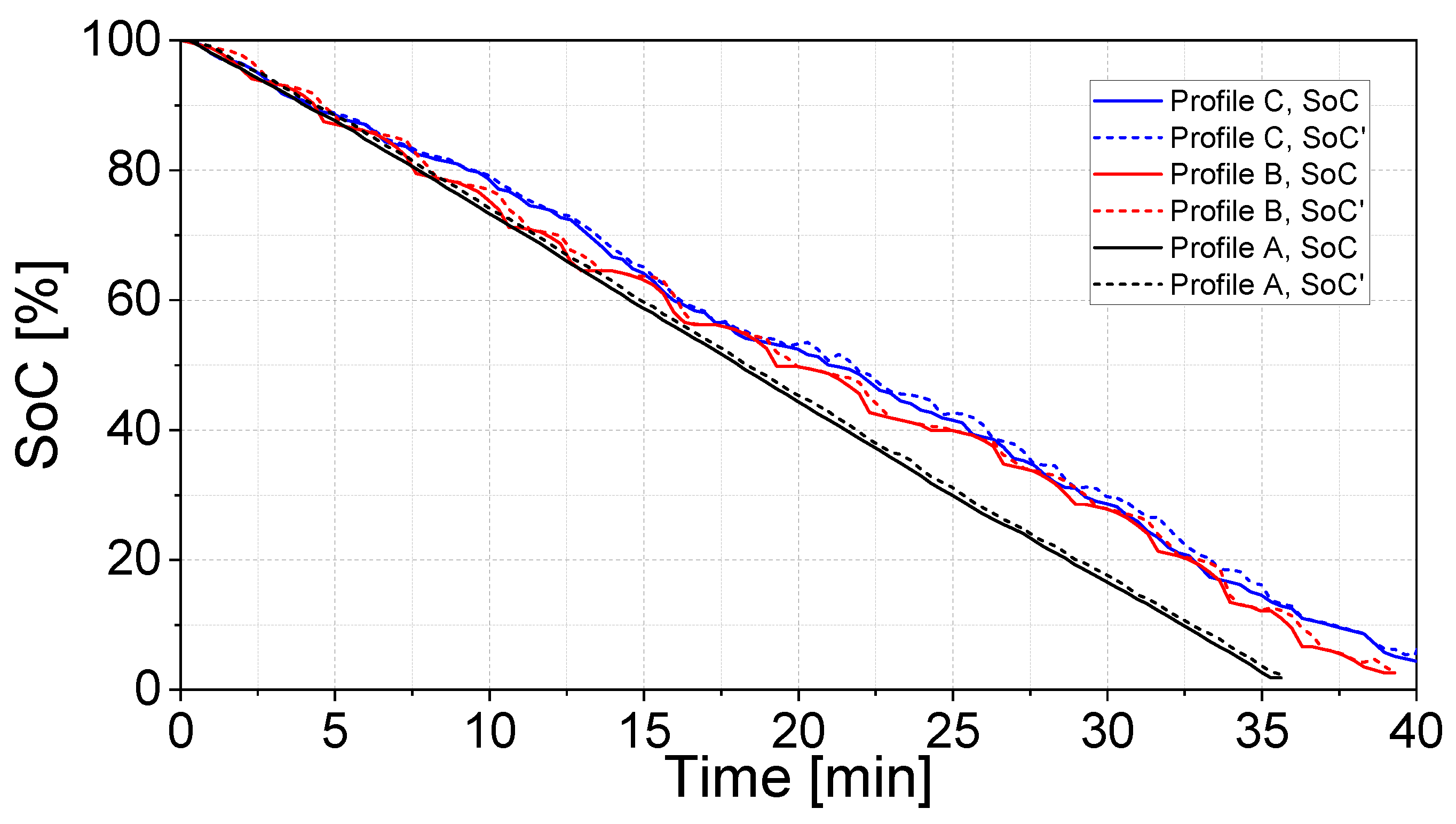

- Determine and the efficiency losses of the microturbine. In the first term, considering that the microturbine was based on a Savonius rotor [66]. was given according to Equation (8).where = , with representing the mechanical efficiency and denoting the generator efficiency of the microturbine.It is assumed that is the power coefficient and is the available wind power calculated using Equation (9), where = , H is the height of the rotor in m, D is the diameter of the rotor in m, is the air density in kg/m3, and v is the wind speed in m/s.Assuming that = 0.95 due to the direct gear system with minimal friction, = 0.7 reflecting the simplicity of the microturbine electronics, and = 0.923 kg/m3 at 27 °C and 2000 m altitude, was given by Equation (10). Since the power coefficient of the Savonius microturbine is usually between 0.15 and 0.25, a worst-case scenario was assumed, and was set to 0.15.Similar to Figure 9, Figure 10 shows the harvested electric power, , for driving profiles A (black), B (red), and C (blue).Using battery power data (Figure 9) and microturbine output (Figure 10), Figure 11 illustrates how the integration of two microturbines reduced the power demand of the Li-Po battery over time across driving profiles A, B, and C, assuming that = . Figure 11 shows that by integrating two microturbines, the energy demand was reduced to 97.21%, 98.06%, and 95.64% for the driving profiles A, B, and C, respectively. In this way, the use of two microturbines suggests that the battery life could be extended by up to 2.79%, 1.94%, and 4.36% for driving profiles A, B, and C, respectively. This gain is proportional to the reduced energy demand from harvested power.As demonstrated in Figure 12, the results indicate enhancements in the SoC of the battery, attributable to the energy yield of the microturbine-based energy harvester. Note that SoC’ represents the estimated SoC when the wind energy harvester was used in the EV.To confirm that the microturbine rotational speed, n, ranged from 0 to 25,000 RPM as indicated in Section 3.4, Equation (11) was considered.Note that is a dimensionless quantity representing the specific speed of the microturbine. For a Savonius system, 1, since the tangential speed at the end of the rotor vanes is nearly equal to the wind speed. During the experiments, n ranged from 0 to 2800 RPM, which is well within the operating range of 25,000 RPM for the motor. The efficiency losses for any wind speed could be estimated using Equation (12).Note that L was estimated using the worst-case scenario for a Savonius microturbine, with = 0.95 and = 0.7.

- Determine . Figure 13 shows calculated using Equation (3), which accounts for how the speed of the electric vehicle impacted for each driving profile. Table 5 shows a summary and comparison of the results from the three driving profiles.Note that with only two microturbines () and assuming W under driving profile A, each harvester must supply at least 50 W. To achieve this, the EV must maintain a speed greater than v = 27.88 m/s (100.36 km/h). However, such conditions increase power demands under other profiles.

3.5. Aerodynamic Drag Introduced by Microturbines

4. Discussion

4.1. Energy Requirements in an Electric Vehicle

4.2. Comparison Between Wind Energy Harvesters and Ambient RF Energy Harvesters

4.3. Comparison Between Wind Energy Harvesters and Photovoltaic Harvesters

4.4. Advantages of Experimental Design

4.5. Perspectives and Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| BMS | Battery management system |

| CFD | Computational fluid dynamic |

| C-rates | Discharge rates |

| DC | Direct current |

| EPA | Environmental Protection Agency |

| EV | Electric vehicle |

| IoT | Internet of Things |

| LED | Light-emitting diode |

| Li-Po | Lithium-polymer |

| MPPT | Maximum power point tracking |

| NTC | Negative temperature coefficient |

| RF | Radio frequency |

| RPM | Revolutions per minute |

| SoC | State of Charge |

| SST | Shear stress transport |

| SoH | State of health |

| VAWT | Vertical-axis wind turbine |

References

- Umamaheswari, B.; Santhosh, S.; Ulugbek, A.; Singh, R.; Abbas, A.H.R.; Sherje, N.P. Innovative approaches to harvesting and storing renewable energy from ambient sources. E3S Web Conf. 2024, 540, 13016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, M.; Yeo, W.H. Advances in energy harvesting technologies for wearable devices. Micromachines 2024, 15, 884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishanth, J.R.; Senthilkumar, B. Hybrid energy harvesting by reverse di-electric on a piezo-electric generator with thermo-couple and monitoring in WSN. Automatika 2024, 65, 738–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Ma, S.; Gao, P.; Guo, Y.; Sun, J.; Qiao, D.; Ma, B.; Yuan, W.; Ramakrishna, S.; Ye, T. The state-of-the-art fundamentals and applications of micro-energy systems on chip (MESOC). Natl. Sci. Open 2025, 4, 20240044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adhikari, C. High-efficiency nanostructured materials for flexible and wearable energy harvesting technologies. EPJ Web Conf. 2025, 325, 01002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, L.; Kou, F.; Wang, G.; Liu, P.; Lv, W.; Yang, C. Energy recovery and energy-saving control of a novel hybrid electromagnetic active suspension system for electric vehicles. Energy 2025, 335, 138030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Luo, M.; Tan, C.A. Ride comfort and energy harvesting of inflatable hydraulic-electric regenerative suspension system for heavy-duty vehicles. J. Mech. Sci. Technol. 2024, 38, 2277–2289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behara, N.S.R.; Rao, P.S. Vibration energy harvesting using telescopic suspension system for conventional two-wheeler and EV. Res. Eng. Struct. Mater. 2023, 9, 687–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Guo, X.; Liu, W.; Lee, C. Recent progress in the energy harvesting technology—From self-powered sensors to self-sustained IoT, and new applications. Nanomaterials 2021, 11, 2975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Oliveira, T.; Girardi, A.; De Aguirre, P.C.; Severo, L. A 915 MHz closed-loop self-regulated RF energy harvesting system for batteryless devices. J. Integr. Circuits Syst. 2023, 18, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosseini, S.M.; Soleymani, M.; Kelouwani, S.; Amamou, A.A. Energy recovery and energy harvesting in electric and fuel cell vehicles, a review of recent advances. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 83107–83135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mhatre, A.S.; Shukla, P. A comprehensive review of energy harvesting technologies for sustainable electric vehicles. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Z.; Zhou, Y.; Zhang, J.; Foroughi, J.; Peng, S.; Baughman, R.H.; Wang, Z.L.; Wang, C.H. Advanced energy harvesters and energy storage for powering wearable and implantable medical devices. Adv. Mater. 2024, 36, 2404492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, A.; Shaukat, H.; Elahi, H.; Taimur, S.; Manan, M.Q.; Altabey, W.A.; Kouritem, S.A.; Noori, M. Advancements in energy harvesting techniques for sustainable IoT devices. Results Eng. 2025, 26, 104820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Safaei, B.; Peiravian, M.; Siamaki, M. Eco-friendly IoT: Leveraging energy harvesting for a sustainable future. IEEE Sens. Rev. 2025, 2, 32–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, Z.M.; Anbalagan, R.; Jayabalakrishnan, D.; Naga Muruga, D.B.; Prabhahar, M.; Bhaskar, K.; Sendilvelan, S. Charging of car battery in electric vehicle by using wind energy. Mater. Today Proc. 2021, 45, 5873–5877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Surendran, A.; Baig, A.; Acharya, R.K. Smart energy harvesting in electric vehicles: Integrating automation for enhanced sustainability. Int. J. Res. Publ. Rev. 2023, 4, 1650–1662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helera, C.; Stoichescu, D.A. Utilizing relative wind energy for dynamic charging in electric and hybrid vehicles. In Wind Power—From Energy Conversion to Technological and Operational Challenges; Ismail, D.B.I.A., Ed.; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2025; Volume Chapter 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dinh Le, A.; Minh, B.D.; Trinh, C.D. High efficiency energy harvesting using a Savonius turbine with multicurve and auxiliary blade. J. Fluids Eng. 2022, 144, 111207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arbiyani, F.; Lasut, F.P. Design of Savonius vertical axis wind turbine for vehicle. J. Mech. Eng. Sci. Technol. 2020, 4, 125–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamran Khan, M.; Hamza Zafar, M.; Riaz, T.; Mansoor, M.; Akhtar, N. Enhancing efficient solar energy harvesting: A process-in-loop investigation of MPPT control with a novel stochastic algorithm. Energy Convers. Manag. X 2024, 21, 100509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, H.; Na, J.; Zhou, W.; Hur, S.; Chien, P.M.; Wang, C.; Wang, L.; Yamauchi, Y.; Yuan, Z. Enhancing energy harvesting performance and sustainability of cellulose-based triboelectric nanogenerators: Strategies for performance enhancement. Nano Energy 2023, 116, 108769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mondal, A.; Gautam, A.K.; Khare, N. Boosting electrical efficiency in hybrid energy harvesters by scavenging ambient thermal and mechanical energy. Energy Convers. Manag. 2025, 332, 119739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sevcik, P.; Sumsky, J.; Baca, T.; Tupy, A. Self-sustaining operations with energy harvesting systems. Energies 2025, 18, 4467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nkele, A.; Ikhioya, I.; Chime, C.; Ezema, F. Improving the performance of solar thermal energy storage systems. J. Energy Power Technol. 2023, 5, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, S.Y.; Rauf, S.; Liu, S.; Chen, W.; Shen, Y.; Kumar, M. Revolutionizing the solar photovoltaic efficiency: A comprehensive review on the cutting-edge thermal management methods for advanced and conventional solar photovoltaics. Energy Environ. Sci. 2025, 18, 1130–1175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guarino, S.; Lo Brano, V.; Kosny, J. Understanding the transformative potential of solar thermal technology for urban sustainability. Front. Sustain. Cities 2025, 7, 1583316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Appalasamy, K.; Mamat, R.; Kumarasamy, S. Smart thermal management of photovoltaic systems: Innovative strategies. AIMS Energy 2025, 13, 309–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Li, Y.Z.; Yuan, M. Requirements, challenges, and novel ideas for wearables on power supply and energy harvesting. Nano Energy 2023, 115, 108715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogdakis, K.; Psaltakis, G.; Fagas, G.; Quinn, A.; Martins, R.; Kymakis, E. Hybrid chips to enable a sustainable internet of things technology: Opportunities and challenges. Discov. Mater. 2024, 4, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdulmalek, S.; Nasir, A.; Jabbar, W.A. LoRaWAN-based hybrid internet of wearable things system implementation for smart healthcare. Internet Things 2024, 25, 101124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, A.; Shaukat, H.; Bibi, S.; Altabey, W.A.; Noori, M.; Kouritem, S.A. Recent progress in energy harvesting systems for wearable technology. Energy Strategy Rev. 2023, 49, 101124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prasad, P.V.; Mallala, B.; Chinnave, S.; Arunachalam, K.P. Enhanced energy management in IoT-assisted hybrid microgrids through builder optimization algorithm and neural architecture search-guided physics-informed neural network. Wind. Eng. 2025, 0309524X251389729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manivannan, R. Research on IoT-based hybrid electrical vehicles energy management systems using machine learning-based algorithm. Sustain. Comput. Inform. Syst. 2024, 41, 100943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, J. The convergence of internet of things and electric vehicles: A path toward smarter charging solutions. Intell. Decis. Technol. 2025, 19, 3692–3706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Soham, D.; Liang, Z.; Wan, J. Advances in wearable energy storage and harvesting systems. Med-X 2025, 3, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, X.; Manthiram, A. Sustainable battery materials for next-generation electrical energy storage. Adv. Energy Sustain. Res. 2021, 2, 2000102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bao, J.; Mao, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Jiang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Yang, Y. A data-driven-aided thermoelectric equivalent circuit model for accurate temperature prediction of Lithium-ion batteries. Int. J. Energy Res. 2024, 2024, 5544635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.K.; Raza, M.; Shahbaz, M.; Farooq, U.; Akram, M.U. Recent advancement in energy storage technologies and their applications. J. Energy Storage 2024, 92, 112112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adeyinka, A.M.; Esan, O.C.; Ijaola, A.O.; Farayibi, P.K. Advancements in hybrid energy storage systems for enhancing renewable energy-to-grid integration. Sustain. Energy Res. 2024, 11, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alphonse Raj, R.; Raaju Sundhar, A.S.; Bejigo, K.S.; Kim, S. Interfacial engineering with Lithium Titanate on MCMB anode for Lithium-ion batteries. Energy Environ. Mater. 2025, e70099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srivastava, S.K.; Awasthi, H.; Hota, C.; Goel, S. Synthetic data–based approach for supercapacitor characterization and areal capacitance optimization using cyclic voltammetry data. Int. J. Energy Res. 2024, 2024, 3993551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czagany, M.; Hompoth, S.; Keshri, A.K.; Pandit, N.; Galambos, I.; Gacsi, Z.; Baumli, P. Supercapacitors: An efficient way for energy storage application. Materials 2024, 17, 702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shuja, A.; Khan, H.R.; Murtaza, I.; Ashraf, S.; Abid, Y.; Farid, F.; Sajid, F. Supercapacitors for energy storage applications: Materials, devices and future directions: A comprehensive review. J. Alloys Compd. 2024, 1009, 176924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iqbal, M.F.; Nasir, F.; Shabbir, F.; Babar, Z.U.D.; Saleem, M.F.; Ullah, K.; Sun, N.; Ali, F. Supercapacitors: An emerging energy storage system. Adv. Energy Sustain. Res. 2025, 6, 2400412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Liu, X.; Wang, S.; Liu, H.K.; Li, L. Transition metal based battery-type electrodes in hybrid supercapacitors: A review. Energy Storage Mater. 2020, 28, 122–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benoy, S.M.; Pandey, M.; Bhattacharjya, D.; Saikia, B.K. Recent trends in supercapacitor-battery hybrid energy storage devices based on carbon materials. J. Energy Storage 2022, 52, 104938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almusawi, M.; Shukla, A.; S., H.; Kavitha, P.; Gambhire, G.M.; Pardeshi, P.R.; Pragathi, B. Comparative analysis of supercapacitors vs. batteries. E3S Web Conf. 2024, 591, 01010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muralee Gopi, C.V.V.; Alzahmi, S.; Narayanaswamy, V.; Vinodh, R.; Issa, B.; Obaidat, I.M. Supercapacitors: A promising solution for sustainable energy storage and diverse applications. J. Energy Storage 2025, 114, 115729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabeyi, M.J.B.; Olanrewaju, O.A. Smart grid technologies and application in the sustainable energy transition: A review. Int. J. Sustain. Energy 2023, 42, 685–758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, D.; Song, C.K.; Lee, G.; Song, W.; Park, S. A comprehensive review of battery-integrated energy harvesting systems. Adv. Mater. Technol. 2024, 9, 2302236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheng, H.; Ma, Y.; Zhang, H.; Yuan, J.; Li, F.; Li, W.; Xie, E.; Lan, W. Integration of supercapacitors with sensors and energy-harvesting devices: A review. Adv. Mater. Technol. 2024, 9, 2301796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lund, H.; Østergaard, P.A.; Connolly, D.; Mathiesen, B.V. Smart energy and smart energy systems. Energy 2017, 137, 556–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammadi, M.; Noorollahi, Y.; Mohammadi-Ivatloo, B. An introduction to smart energy systems and definition of smart energy hubs. In Operation, Planning, and Analysis of Energy Storage Systems in Smart Energy Hubs; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Yan, C.; Liu, H.; Wang, J.; Yang, Z.; Jiang, Y. Smart energy systems: A critical review on design and operation optimization. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2020, 62, 102369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kechida, A.; Gozim, D.; Toual, B.; Alharthi, M.M.; Agaije, T.F.; Ghoneim, S.M.S.; Ghaly, R.N.R. Smart control and management for a renewable energy based stand-alone hybrid system. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 32039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yaseen, D.; Qays, H.; Abdulkareem, H.; Ahmed, F. Enhancing energy efficiency utilized IoT: Power optimization and energy harvesting techniques for sustainable and resilient systems. J. Educ. Sci. 2025, 34, 45–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lohse-Busch, H.; Duoba, M.; Rask, E.; Stutenberg, K.; Gowri, V.; Slezak, L.; Anderson, D. Ambient Temperature (20 °F, 72 °F and 95 °F) Impact on Fuel and Energy Consumption for Several Conventional Vehicles, Hybrid and Plug-in Hybrid Electric Vehicles and Battery Electric Vehicle; SAE Technical Paper Series; SAE International: Warrendale, PA, USA, 2013; p. 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United States, Department of Energy and Environmental Protection Agency, Office of Energy Efficiency and Renewable Energy. Where the Energy Goes: Electric Cars. 2017. U.S. Government Source for Fuel Economy Information. Available online: https://www.fueleconomy.gov/feg/atv-ev.shtml (accessed on 30 October 2025).

- Balasingam, B.; Ahmed, M.; Pattipati, K. Battery management systems—Challenges and some solutions. Energies 2020, 13, 2825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Movassagh, K.; Raihan, A.; Balasingam, B.; Pattipati, K. A critical look at Coulomb counting approach for State of Charge estimation in batteries. Energies 2021, 14, 4074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, S.; Samanta, S.; Gupta, S. Online state-of-charge estimation by modified Coulomb counting method based on the estimated parameters of lithium-ion battery. Int. J. Circuit Theory Appl. 2023, 52, 749–768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montgomery, D.C. Design and Analysis of Experiments, 10th ed.; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Box, G.E.P.; Hunter, J.S.; Hunter, W.G. Statistics for Experimenters, 2nd ed.; Wiley Series in Probability and Statistics; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, J.; Lee, J. A review on prognostics and health monitoring of Li-ion battery. J. Power Sources 2011, 196, 6007–6014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohamed, M.H.; Alqurashi, F.; Thévenin, D. Performance enhancement of a Savonius turbine under effect of frontal guiding plates. Energy Rep. 2021, 7, 6069–6076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El, E.; Yildiz, C.; Dandil, B.; Yildiz, A. Effect of wind turbine designed for electric vehicles on aerodynamics and energy performance of the vehicle. Therm. Sci. 2022, 26, 2907–2917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yildiz, A.; Dandil, B. Influence of wind turbine mounted on vehicle on aerodynamic drag and energy gain. Sci. Iran. 2025, in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sofian, M.; Nurhayati, R.; Rexca, A.J.; Syariful, S.S.; Aslam, A. An evaluation of drag coefficient of wind turbine system installed on moving car. Appl. Mech. Mater. 2014, 660, 689–693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogowski, K.; Maroński, R. CFD computation of the Savonius rotor. J. Theor. Appl. Mech. 2015, 53, 37–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nabavi, S.; Zhang, L. Portable wind energy harvesters for low-power applications: A survey. Sensors 2016, 16, 1101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calautit, K.; Nasir, D.S.N.M.; Hughes, B.R. Low power energy harvesting systems: State of the art and future challenges. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2021, 147, 111230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yathavi, T.; Maunasree, K.; Meenakshi, G.B.; Malika, M.V.; Santhoshini, M. RF energy harvesting for low power applications. In Proceedings of the 2021 10th International Conference on Internet of Everything, Microwave Engineering, Communication and Networks (IEMECON), Jaipur, India, 1–2 December 2021; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2021; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.H.; Kim, S.J.; Kim, S.; Oh, J.I.; Lee, C.H.; Yu, J.W. Feasibility analysis of ambient RF energy harvesting for low-power IoT devices. In Proceedings of the 2022 International Symposium on Antennas and Propagation (ISAP), Sydney, Australia, 31 October–3 November 2022; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2022; pp. 329–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, J.; Li, Z.; Zhang, H. Low-wind-speed galloping wind energy harvester based on a W-shaped bluff body. Energies 2024, 17, 958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, B.; Guo, T.; Alam, M.M. A review of wind energy harvesting technology: Civil engineering resource, theory, optimization, and application. Appl. Energy 2025, 389, 125771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bzzou, M.; Karfa Bekali, Y.; El Bhiri, B. RF energy-harvesting systems: A systematic review of receiving antennas, matching circuits, and rectifiers. Eng. Proc. 2025, 112, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, S.; Yu, H.; Niu, S.; Jian, L. Power loss analysis and thermal assessment on wireless electric vehicle charging technology: The over-temperature risk of ground assembly needs attention. Appl. Energy 2020, 275, 115344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, D.; Qi, L.; Tairab, A.M.; Ahmed, A.; Azam, A.; Luo, D.; Pan, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Yan, J. Solar energy harvesting technologies for PV self-powered applications: A comprehensive review. Renew. Energy 2022, 188, 678–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roga, S.; Bardhan, S.; Kumar, Y.; Dubey, S.K. Recent technology and challenges of wind energy generation: A review. Sustain. Energy Technol. Assessments 2022, 52, 102239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhatt, K.; Kumar, S.; Kumar, S.; Sharma, S.; Singh, V. A review on energy harvesting technologies: Comparison between non-conventional and conceptual approaches. Energy Rep. 2024, 12, 4717–4740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, H.; Lu, J.; Zhang, W.; Yang, G.; Zhang, W.; Xu, Z.; Wang, H.; Dai, K.; Gao, L. Advancements and future prospects of energy harvesting technology in power systems. Micromachines 2025, 16, 964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saha, C.R.; Huda, M.N.; Mumtaz, A.; Debnath, A.; Thomas, S.; Jinks, R. Photovoltaic (PV) and thermo-electric energy harvesters for charging applications. Microelectron. J. 2020, 96, 104685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, S.; Liu, C. Overview of energy harvesting and emission reduction technologies in hybrid electric vehicles. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2021, 147, 111188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bentouba, S.; Zioui, N.; Breuhaus, P.; Bourouis, M. Overview of the potential of energy harvesting sources in electric vehicles. Energies 2023, 16, 5193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angamarca-Avendaño, D.A.; Flores-Vázquez, C.; Cobos-Torres, J.C. A photovoltaic and wind-powered electric vehicle with a charge equalizer. Energies 2024, 17, 4665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Feature | Energy Harvester | Li-Po Batteries |

|---|---|---|

| Output power | Extremely low (μW to mW). | Substantially high (tens to hundreds of watts) with even higher capacities in electric mobility applications. |

| Energy source | Ambient, intermittent, and unpredictable (wind, solar, vibration, RF, heat). | Internal stored self-contained chemical energy. |

| Energy density | Extremely low. | High (150–250 Wh/kg). |

| Conversion efficiency | Limited (10–50%, source-dependent). | High (>90%). |

| Longevity | Practically unlimited (absent chemical degradation). It depends on power source availability and is affected by component wear and environmental conditions. 1 | Limited (300–500 cycles typical for Li-Po). |

| Applications | Ultra-low power wireless sensor networks, implantable biomedical devices, and wearable wearable-mounted electronics. | Smartphones, laptops, and electric vehicles. |

| Maintenance | Minimal, generally self-sustaining once deployed. | Requires periodic monitoring and proper charging. |

| Environmental impact | Low. | Moderate to high (mining, disposal issues). |

| Component | Parameter | Specifications |

|---|---|---|

| Electric vehicle | Length | 379 mm |

| Width | 200 mm | |

| Height | 62 mm | |

| Weight | 1.44 kg | |

| Wheel diameter | 66 mm | |

| Transmission | Single speed direct drive | |

| Battery-Traxxas 3 Cell | Technology | Li-Po |

| Total capacity, | 5000 mAh | |

| Nominal voltage | 11.1 V | |

| Continuous discharge | 125 A | |

| Maximum explosion speed | 250 A | |

| Watt Hours | 55.5 | |

| Loading rate | 5 A | |

| Maximum load rate | 10 A | |

| Dimensions | 155 mm × 26 mm × 44 mm | |

| Weight | 376 g | |

| Discharge cut-off voltage 1 | 9.25 V | |

| Temperature range (charging condition) | 0 °C to 43 °C | |

| Temperature range (discharging condition) | 0 °C to 60 °C | |

| Temperature range (storage condition) 2 | 15 °C to 25 °C | |

| Velineon 3500 motor | Technology | Brushless |

| RPM/volt | 3500 | |

| Max RPM | 50,000 | |

| Magnet type | Neodymium | |

| Connection type | 3.5 mm | |

| Current | 65 A to 100 A | |

| Diameter | 36 mm | |

| Length | 55 mm | |

| Weight | 262 g |

| Sensor | Parameter | Technical Specifications | Additional Information |

|---|---|---|---|

| ESP32 ADC | Voltage | Range: 0–33 V | Voltage divider 1:10 |

| Sensitivity: 3.3 mV/LSB | |||

| Resolution: 10 bits | |||

| Modified INA219 | Current | Range: 0–32 A | Modified for high currents |

| : 0.01 Ω (original 0.1 Ω) | Accuracy: ±1%. | ||

| Resolution: 15 bits | |||

| KY-013 | Temperature | Range: −55 °C to 125 °C | Thermistor NTC 10 kΩ |

| Accuracy: ±0.5 °C. | Linearized by software | ||

| Low energy consumption | Resolution: 10 bits | ||

| Dimensions: 22 mm × 15 mm × 9 mm | Steinhart-Hart coefficients: | ||

| A = 0.001129148, | |||

| B = 0.000234125, and | |||

| C = 0.0000000876741 |

| Parameter | Profile A | Profile B | Profile C |

|---|---|---|---|

| Final (%) | 1.80 | 5.11 | 4.44 |

| Time (min) | 36 | 39 | 40 |

| Final (V) | 9.58 | 9.38 | 9.68 |

| Battery temperature (°C) | 21.5 to 26.75 | 23 to 27 | 22 to 28 |

| Traveled distance (km) | 17.49 | 13.48 | 17.12 |

| Parameter | Profile A | Profile B | Profile C |

|---|---|---|---|

| Average of [W] | 1.35 ± 0.26 | 1.08 ± 1.30 | 1.48 ± 1.47 |

| Minimum of [devices] | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Average of [devices] | 71 | 327 | 405 |

| Maximum of [devices] | 122 | 4905 | 4672 |

| Usage and Losses | City & Highway | City | Highway |

|---|---|---|---|

| Charging battery | 10% | 10% | 10% |

| Auxiliary electric | 0–4% | 0–6% | 0–2% |

| Energy to wheels | 65–69% | 60–66% | 71–73% |

| Electric drive system | 18% | 20% | 15% |

| Accessories | 3% | 4% | 2% |

| Idle | 0% | 0% | 0% |

| Energy recovered from regenerative braking | 22% | 34% | 6% |

| Driving Profile | Energy Covered (Auxiliary Electric, %) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| A (average values) | 92.2880 | 0.1102 | 0.1194 | 0.0398 |

| A (max values) | 121.6675 | 0.2050 | 0.1685 | 0.0561 |

| B (average values) | 66.6996 | 0.0888 | 0.1331 | 0.0444 |

| B (max values) | 165.9492 | 0.3646 | 0.2197 | 0.0732 |

| C (average values) | 79.6508 | 0.1208 | 0.1517 | 0.0506 |

| C (max values) | 173.3424 | 0.4332 | 0.2499 | 0.0833 |

| Feature | Wind Energy Harvesters (Small-Scale) | Ambient RF Energy Harvesters |

|---|---|---|

| Energy source | Kinetic energy of moving air. | Ambient electromagnetic energy. |

| Power output | mW to W. Capable of powering more demanding electronic systems. | μW to tens of μW. Suitable only for ultra-low-power devices. |

| Environment | Operates most effectively in outdoors. | Operates reliably both indoors and outdoors. |

| Physical size | Typically ranges from few cm to meters. | Generally sub-centimeter in scale. |

| Maintenance | Higher. Subject to wear and tear. | Lower/None. Solid-state components with no moving parts. |

| Appearance | Potential visual and acoustic pollution even at small scales. | Invisible and silent. |

| Applications | Remote sensing and monitoring, IoT, low-power street lighting. | Wireless sensor networks, RFID tags, implantable medical devices, and battery-free IoT devices. |

| Feature | Wind Energy Harvesters (Small-Scale) | Photovoltaic Energy Harvesters |

|---|---|---|

| Energy source | Kinetic energy of moving air. | Solar radiation. |

| Time dependence | Supplies energy day and night with sufficient wind. | Output varies with light intensity and cloud cover. |

| Form factor and size | Requires a large swept area Miniaturization is difficult. | Well-suited for integration on surfaces like roofs or casings. |

| Location suitability | Areas with consistent, high-speed wind. | Areas with high solar irradiation. |

| Space/footprint | Uses less land, allowing space for farming or grazing. | Needs a large, flat, shadow-free area for optimal exposure. |

| Installation/Maintenance | Higher. Subject to wear and tear. | Lower complexity and easier installation. |

| Environmental impact | May cause noise, visual impact, and pose risks to birds if poorly sited. | Primarily associated with panel production and land use in large setups. |

| Efficiency | Can achieve high conversion rates, limited by Betz Law. | Typical module efficiency is lower, but systems are often easier to install and scale. |

| Scalability | Challenging—small turbines are inefficient at low wind speeds. | High scalable—small cells power low-duty sensors effectively. |

| Feature | Wind Energy Harvesters (Small-Scale) | Photovoltaic Energy Harvesters |

|---|---|---|

| Energy harvesting | Inefficient—harvested energy is minimal and outweighed by added drag. | Highly efficient—harvests stable energy while parked or driving in sunlight. |

| Integration | Low feasibility due to bulky, noisy turbines that add drag and reduce battery range. | Highly feasible—easily integrated into flat surfaces like the roof or hood. |

| Aesthetics and safety | Low. Not only is it visually disruptive, but its moving parts also pose safety and noise hazards. | Excellent. Flat, sleek, and safe. |

| Practical power | Very slow. Small turbine energy is negligible in electric vehicle power use. | Moderate. It can extend driving range or supply power to low-demand auxiliary systems. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Published by MDPI on behalf of the World Electric Vehicle Association. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Gutiérrez-Rosales, D.; Jiménez-Ramírez, O.; Aguilar-Torres, D.; Paredes-Rojas, J.C.; Carvajal-Quiroz, E.; Vázquez-Medina, R. Energy Harvesting Devices for Extending the Lifespan of Lithium-Polymer Batteries: Insights for Electric Vehicles. World Electr. Veh. J. 2025, 16, 682. https://doi.org/10.3390/wevj16120682

Gutiérrez-Rosales D, Jiménez-Ramírez O, Aguilar-Torres D, Paredes-Rojas JC, Carvajal-Quiroz E, Vázquez-Medina R. Energy Harvesting Devices for Extending the Lifespan of Lithium-Polymer Batteries: Insights for Electric Vehicles. World Electric Vehicle Journal. 2025; 16(12):682. https://doi.org/10.3390/wevj16120682

Chicago/Turabian StyleGutiérrez-Rosales, David, Omar Jiménez-Ramírez, Daniel Aguilar-Torres, Juan Carlos Paredes-Rojas, Eliel Carvajal-Quiroz, and Rubén Vázquez-Medina. 2025. "Energy Harvesting Devices for Extending the Lifespan of Lithium-Polymer Batteries: Insights for Electric Vehicles" World Electric Vehicle Journal 16, no. 12: 682. https://doi.org/10.3390/wevj16120682

APA StyleGutiérrez-Rosales, D., Jiménez-Ramírez, O., Aguilar-Torres, D., Paredes-Rojas, J. C., Carvajal-Quiroz, E., & Vázquez-Medina, R. (2025). Energy Harvesting Devices for Extending the Lifespan of Lithium-Polymer Batteries: Insights for Electric Vehicles. World Electric Vehicle Journal, 16(12), 682. https://doi.org/10.3390/wevj16120682