1. Introduction

The world is experiencing a revolution in transportation electrification, and the sales of plug-in electric vehicles (PEVs) have been explosively growing since 2010 [

1]. By the end of 2019, the global stock of plug-in electric passenger vehicles was more than 7 million [

2]. The share of PEV annual sales in the global vehicle market reached 2.5% in 2019, an increase from the 2.2% market share in 2018 [

3]. China contributes significantly to the development of the global PEV market, amounting to around 45% of PEV passenger vehicles on the road in 2018 [

4]. However, the pathway of PEV development has not always been easy in China. The vehicle market in China experienced downturns for two successive years (2018–2020), and this gloomy atmosphere also explicitly spread to its PEV sales. In 2019, the PEV sales in China were just over 1.2 million [

3], which dropped about 4% off from 1.25 million PEV sales in 2018 [

5]. In 2020, the COVID-19 pandemic and its social and economic impacts also brought new challenges to the development of Chinese vehicle market [

6]. Meanwhile, even though the Chinese economy faced unprecedented uncertainties in 2020, the annual sales of passenger PEVs were estimated to be about 1.246 million units in 2020, reaching a new sales record in the Chinese market [

7]. The development of the electric vehicle industry is much faster than the vehicle industry as a whole, and it will lead the development of the Chinese manufacturing, especially the green energy industry [

7]. Nevertheless, future sales of PEVs still face uncertainties due to consumer perception, charging infrastructure deployment, technology progress, and even potential new policies [

8]. Therefore, the market dynamics of the electric vehicle market development in China is of great interest to the stakeholders from industry, policymakers, and academics.

PEV is deemed a critical technological promotion trend and an effective green energy transition pathway in terms of future mobility choices [

9]. Policy orientation has often been adopted as a significant impetus on PEV development in China in order to promote electrified transportation [

1]. The Chinese policies started with a strong demand-pull strategy on the consumer side through subsidizing PEV sales (including subsidies from both central government and local government) or non-monetary incentives such as license plate privilege for PEVs, urban free parking, and free charging pile installation. Although criticized that they could distort the market demand and magnify local protectionism [

1], these incentives motivated the sales of PEVs and enlarged the PEV user community in the early stage of PEV market development. For example, the most powerful non-monetary incentive for PEV purchase is a special priority given for vehicle registration and license plate/PEV license plate privilege, with the estimated value of this policy being about USD 13,060 quantified by Ou et al. (2019) [

9]. This value is equivalent to half of the vehicle’s average price in China [

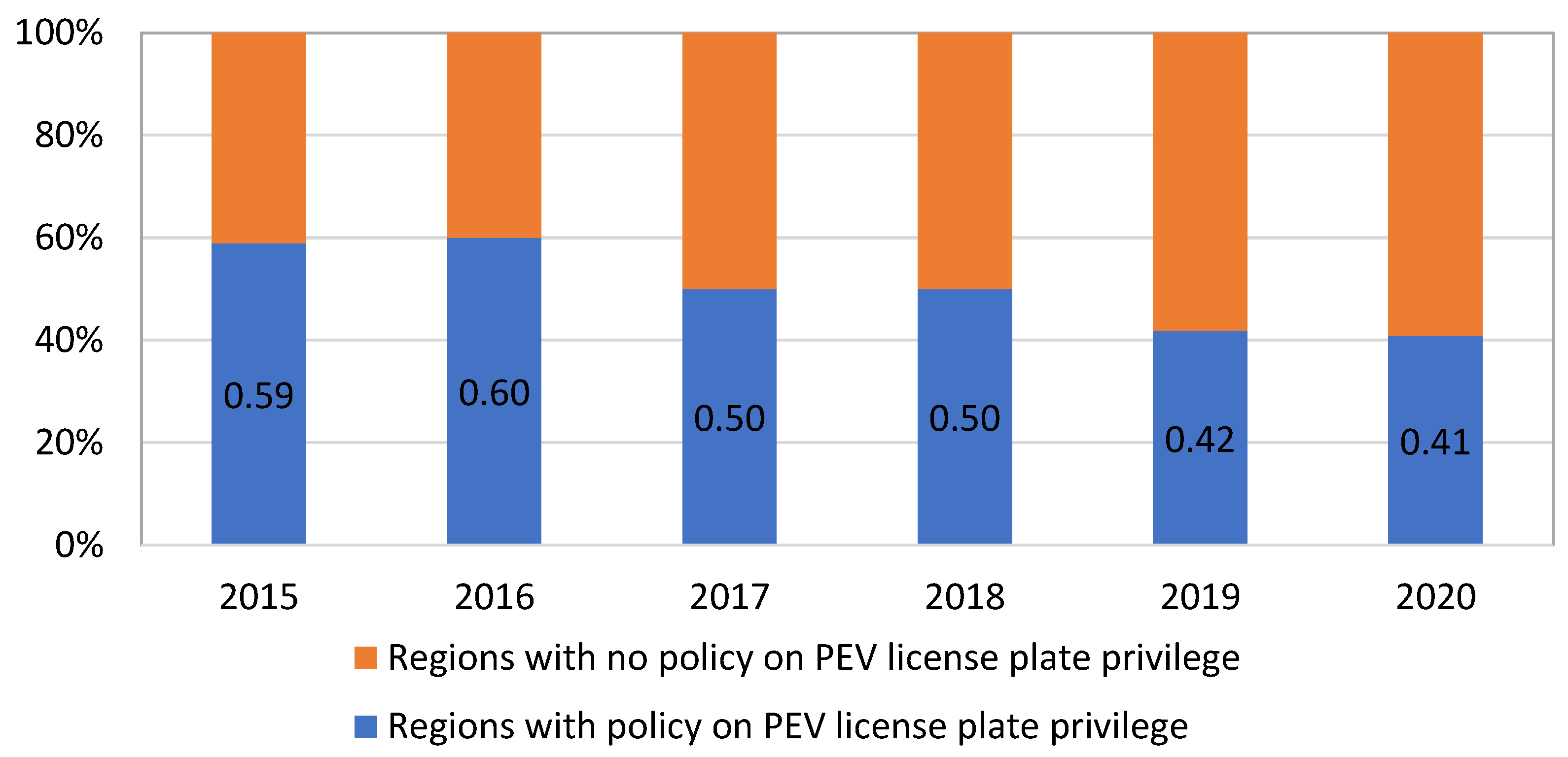

9]. According to the report by Ren et al. (2019), nearly half of the PEVs were purchased by the consumers who live in the regions with policy on PEV license plate privilege, as shown in

Figure 1 [

5].

However, the demand-push brings extra financial burdens to the governments and also causes some problems such as wasting of resources and subsidy cheating [

1]. Therefore, while the Chinese government has promised that it will not end the PEV subsidy at least before the end of 2022 [

10], it intends to transition the PEV support in a more supply-push approach, indicated by the reduction of purchase subsidies, the enforcement of restrictions on corporate average fuel consumption (CAFC) rate, and the implementation of PEV quota policy. In 2017, the Chinese government issued a policy named

Measures for Passenger Cars Corporate Average Fuel Consumption and New Energy Vehicle Credit Regulation (dual credit policy) for the years 2018–2020 to enforce the auto industry to improve the fuel economy of their vehicle products, and more importantly, to divert the auto industry to an electrification path. This policy does not only lessen the financial pressures of direct subsidies by the government, but also avoids the controversial regional protectionisms blamed by stakeholders. At the same time, the government could divert its resources to investing in public charging infrastructure.

After 3 years of implementation, the Chinese government issued a new official version of

Measures for Passenger Cars Corporate Average Fuel Consumption and New Energy Vehicle Credit Regulation (a new version of dual credit policy) for the years 2021–2023 in June 2020 to replace the old version [

11]. The new version of dual credit policy is called dual credit policy (2021–2023) in this study. On the basis of the feedback from the automotive industry and other stakeholders, this vehicle policy formulates the new fuel consumption targets and electric vehicle quotas for the Chinese auto industry in years from 2021 to 2023. This policy is believed to continue to strongly impact the future trends of the vehicle market and the strategies of transportation energy in China [

12]. How are the PEV sales and market impacted by the policy? What type of powertrain technology could benefit from this new policy? Will the downturn of the vehicle industry in 2018–2020 be reversed with the prosperity of electric vehicles? It is essential to answer these questions considering the huge market size and the role of China in global climate change.

Currently, the dual credit policy, adopted only in the passenger vehicles, consists of two sections: the Corporate Average Fuel Consumption (CAFC) credit rules, and the New Energy Vehicle (NEV) credit rules. Similar to the U.S. Corporate Average Fuel Economy Standards, the CAFC credit rules require that the weighted average fuel consumption of vehicles produced or imported by auto companies should be no larger than the required CAFC limit calculated by the Chinese Vehicle Fuel Economy Standards. Auto companies are allowed to accumulate their positive CAFC credits and to use them for the CAFC deficits in other years. Furthermore, similar to the Zero-emission Vehicle Mandate in California, the NEV credit rules in dual credit policy require that the ratio of the PEV numbers to the conventional vehicle numbers from auto companies must be no smaller than a quota. The auto companies can accumulate positive NEV credits and use them for trading or filling the deficits of their CAFC credits. Both the CAFC limit and NEV quota are more stringent year to year to the auto companies in the dual credit policy, so as to increase the share of PEVs in the market.

This study adopted the New Energy and Oil Consumption Credits (NEOCC) model, a vehicle policy analysis tool developed by the Oak Ridge National Laboratory, to quantify the policy impacts on the electric vehicle market in China and to project the future trends of market dynamics through 2023. This paper consists of four sections.

Section 1 presents research motivations and objectives, and generally introduces the current Chinese PEV market.

Section 2 describes the modeling assumptions and modeling approach for the analysis of impacts of the vehicle policies in 2021–2023.

Section 3 presents scenario analyses and provides the market share projection through 2023 under the impacts of dual credit policy (2021–2023). The final section summarizes the conclusions and the future work. In this study, the exchange rate of USD 1.00 is CNY 6.91 (a yearly currency exchange rate in 2019) [

13].

2. Market and Model

The vehicle market data for calibration of the NEOCC model was supplied by the China Automotive Research and Technology Center (CATARC), and the data are the aggregated information on the different vehicle technologies with respect to their annual sales, sales-weighted vehicle prices, sales-weighted fuel economy, and sales-weighted electricity consumption of other vehicle performance indexes in 2016–2019. The aggregated information on the vehicle market in the years 2016–2019 is presented in

Table A1,

Table A2,

Table A3 and

Table A4 (

Appendix A). Moreover, the most recent official version of the dual credit policy (2021–2023) was released in June 2020, and it can be downloaded through the website by China’s Ministry of Industry and Information Technology [

11].

The NEOCC model was firstly released in 2017 and has been improved and integrated with various functions and features in following versions on the basis of user feedback [

14]. The NEOCC model is an optimization model used to capture the dynamic changes of the vehicle market while considering the quantitative impacts from the consumer driving patterns (personal-owned vehicles and public vehicle fleet), the vehicle ownership and production costs, and the government incentives or policy constraints on different powertrain technologies [

15].

Figure 2 shows the algorithm of the NEOCC 2020 model version. The NEOCC model includes the main model section, the consumer information such as time value and travel patterns, the industry dynamics such as production cost and markup factors, the charging infrastructure such as the electricity cost and charging inconvenience cost under different charging scenarios, and the projections for technology evolution and fuel economy requirements in 2020–2050.

The NEOCC model comprehensively considers the vehicle market dynamics with impacts from consumers, government, and the auto industry. It assumes that the auto industry is able to distribute its internal subsidies on different powertrain types of vehicles so as to sell as many cars as possible and maximize its profit. At the same time, the sales and the shares of the vehicle types sold to consumers depend on ownership costs in responding to the vehicle price, driving patterns, charging infrastructure, fuel cost, and so on. The sales and shares by vehicle types are calculated through the method of the nested multinomial logit model. To reach the optimized results, the calculation constantly adjusts the internal subsidies for different vehicle technologies until it is believed that the total profit reaches the largest one. In sum, this NEOCC model integrates the optimization (for example, the genetic algorithm was adopted for 2019 NEOCC model and later versions) for seeking the maximum profits with the discrete choice modelling on allocating the market share of vehicles to the consumers on the basis of their utilities [

14]. For the detailed model algorithms, one can be referred to Ou et al. (2018) [

15] and Ou et al. (2019) [

14].

In this NOECC model version, the shares and the sales of 16 different vehicle powertrain technologies are projected through the discrete choice modelling. The vehicle powertrain types include internal combustion engine vehicle (ICEV), plug-in hybrid electric vehicle (PHEV), and battery electric vehicle (BEV). ICE vehicles are further classified into three categories on the basis of their fuel economy level: ICEVs with a high-fuel consumption rate (ICEV-High), ICEVs with a medium-fuel consumption rate (ICEV-Med), and ICEVs with a low-fuel consumption rate (ICEV-Low, referring to pure hybrid electric vehicles in this model). PHEVs and BEVs are classified on the basis of their electric ranges, with sedans having more classifications than SUVs/crossovers. More detailed classification of these vehicle technologies in 2016–2019 is presented in

Table A1,

Table A2,

Table A3 and

Table A4 (

Appendix A).

In addition, the purchase features and the travel patterns of two consumer types are considered: (a) personal-owned vehicle drivers and (b) public fleet drivers. The probabilities of consumers choosing a particular vehicle type depend on the value of the total ownership cost for each type of vehicle. The total cost of vehicle ownership is summed on the basis of the implicit or explicit values in responding to travel patterns, driver’s incomes (value of time), and personal preferences of consumers, etc. [

14,

15]. For example, the NEOCC model quantifies the costs of vehicle ownership impacted by the charging activities and distributions of electric infrastructure. For a BEV owned by a personal consumer, the total cost of vehicle ownership impacted by charging related activities are estimated through three different perceived costs: the electricity charging costs (at home, at public charging stations, and at workplace), the charging inconvenience cost, and the range anxiety cost [

14]. What is more, this total cost of vehicle ownership impacted by charging-related activities varies depending on whether the consumer owns a dedicated residential parking spot or not [

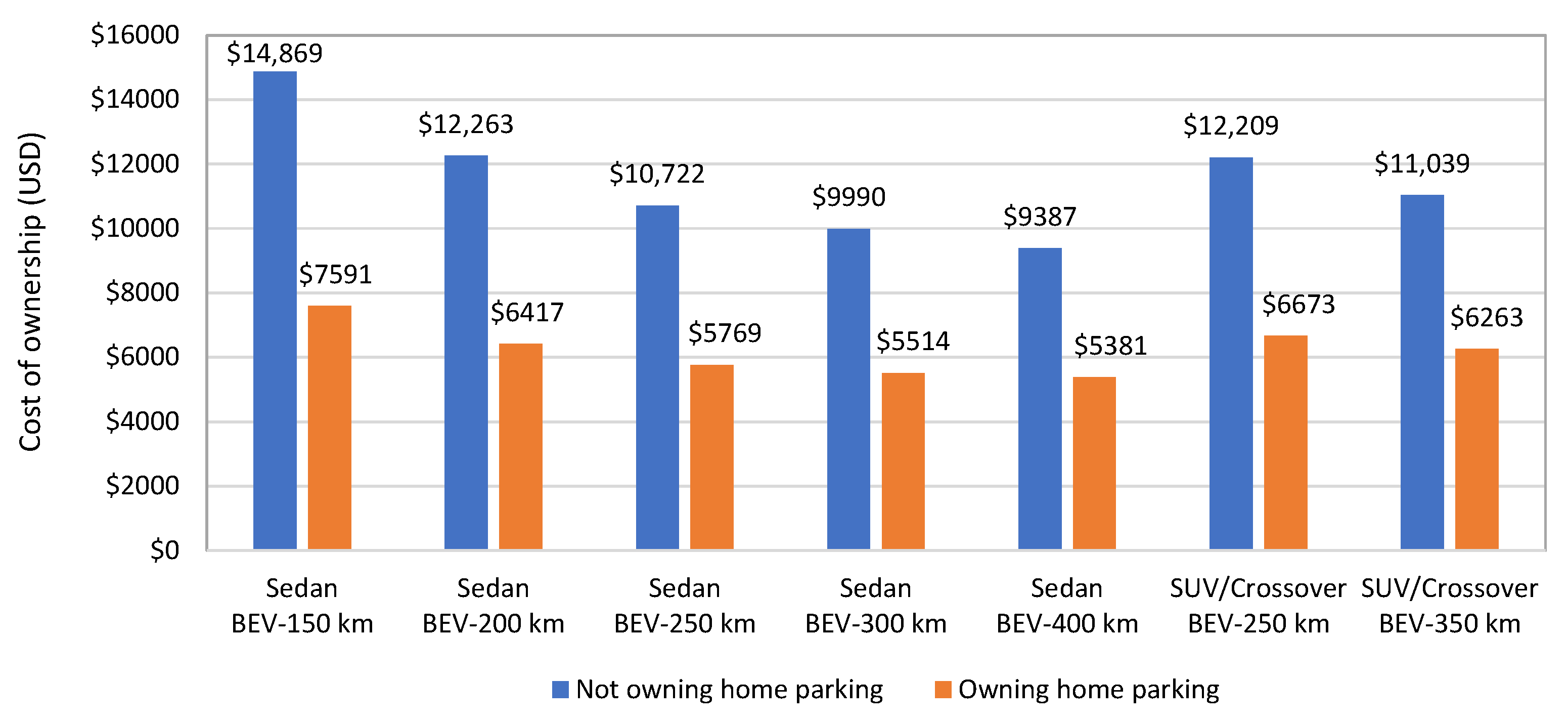

16]. Calculating through the NEOCC model,

Figure 3 reveals the lifetime charging activities costs on individually owning a BEV in 2023. The charging activities include the charging at home, at workplaces, and at public stations with either DC fast charging or slow charging. Additionally, these charging-related costs consider the actual electricity cost, the charging inconvenience cost, the time cost, and the range anxiety cost [

14]. We can see that, by 2023, the sedan BEVs with electric range at 400 km had the lowest cost of ownership related to the charging activities. In addition, owning dedicated residential parking could largely decrease the ownership cost on charging activities by 43–49%, although owning dedicated residential parking is high-cost spending.

Except the explicit and implicit values from consumer travel patterns and charging infrastructure, the monetary and non-monetary incentives from the government are also significant to determine the purchase selection in the vehicle market. The government has confirmed that its subsidies to electric vehicle purchasing will continue at least by the end of 2022 [

10]. Meanwhile, the subsidies will be 10%, 20%, or 30% less than they are in the last year during 2020–2022 [

10]. The subsidies to PEV vehicles also depend on the technical indexes, such as electric range, electricity consumption rate, specific energy density, and maximum speed. For simplification, the subsidies adopted in the NEOCC model only consider the electric range. The maximum subsidies offered by the central government are presented in

Table 1. Moreover, the purchase privilege, which refers to the vehicle license plate privilege for PEVs in major cities in China, is also considered in the NEOCC model. Because of the ratio of PEVs sold to the major cities that still have the vehicle license plate privilege policies becomes less by year, as shown in

Figure 1, the sales weighted purchase privilege is assumed to decrease by year in the NEOCC model. In the NEOCC model 2020 version, the purchase privilege is 30,000 CNY in 2019 and is assumed to linearly decrease to 0 by 2035.

3. Scenario Analysis for Vehicle Market in 2021–2023

To find out the effectiveness of the dual credit policy (2021–2023) in the vehicle market, this study quantified the market evolution of PEVs and ICEV-Low (hybrid electric vehicles) impacted by dual credit policy (2021–2023) and compared it with the market dynamics under different vehicle policies. Four different policy scenarios are simulated in the NEOCC model, and the definitions of these scenarios are described below. Additionally, please note that the monetary incentives to PEVs are also effective in the reference scenario, the CAFC credit-only policy scenario, the NEV credit-only policy scenario, and the old dual credit policy scenario.

Reference scenario: this scenario assumes that the vehicle market is constrained by the dual credit policy (2021–2023).

CAFC credit-only policy scenario: this scenario assumes that the vehicle market is constrained by the CAFC credit rules for 2021–2023 only. Therefore, the fuel consumption of vehicles instead of the PEV quota is the only factor that impacts the industry market strategy.

NEV credit-only policy scenario: this scenario assumes that the vehicle market is constrained by the NEV credit rules for 2021–2023 only. Therefore, the PEV quota instead of the fuel consumption of vehicles is the only factor that impacts the industry market strategy.

Old dual credit policy scenario: this scenario assumes that the dual credit policy (2018–2020) was applied to the vehicle market in 2021–2022. For example, the quota targets on PEV share in 2021–2023 are 8%, 10%, and 12% respectively for 2021–2023, instead of 14%, 16%, and 18% required by the dual credit policy (2021–2023). In addition, the requirements of CAFC credit rules and tested driving cycles are also both changed. In the dual credit policy (2018–2020), the requirement of CAFC is 5 L/100 km under the New European Driving Cycle (NEDC) by 2020 [

17]. In the dual credit policy (2021–2023), the requirement of CAFC is 4.6 L/100 km under the Worldwide Harmonized Light Vehicles Test Cycle (WLTC) by 2023 [

11]. Generally, the fuel consumption rate under WLTC is 10% higher than it under NEDC for the same vehicle [

18]. Consequently, the industry CAFC targets in 2021–2023 are 6.60 L/100 km, 6.05 L/100 km, and 5.50 L/100 km under WLTC, respectively, for 2021–2023, instead of 4.92 L/100 km, 4.8 L/100 km, and 4.6 L/100 km under WLTC required by the dual credit policy (2021–2023) [

11];

Monetary incentives-only scenario: this scenario assumes that the vehicle market is constrained by no dual credit policy (2021–2023) during 2021 and 2023; however, the government subsidies and vehicle license purchase privileges are still in the market to incentivize PEV purchases.

This paper aimed to discuss and compare the short-term (2021–2023) market dynamics impacts under different vehicle policies, and thus we did not focus on the evaluation of model uncertainties by the external factors, which have been discussed by He et al. (2020) [

18].

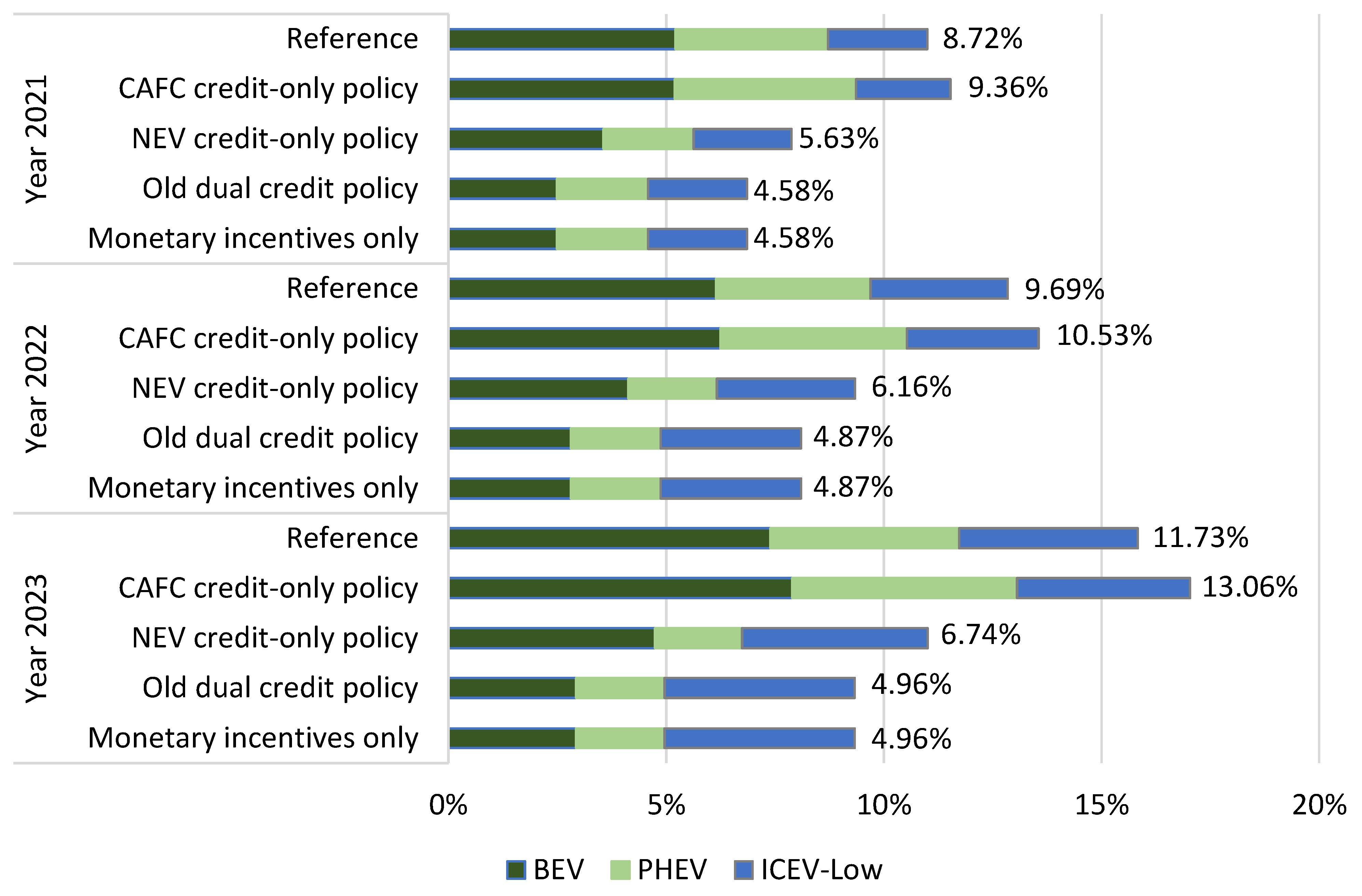

Figure 4 presents the market shares of PEVs and high fuel-efficient ICE vehicles under these four policy scenarios. Three types of vehicle are discussed: BEV, PHEV, and ICEV-Low. The ICEV-Low refers to high fuel-efficient ICEV such as pure hybrid electric vehicles in the NEOCC model.

As shown in

Figure 4, the reference scenario, with the dual-credit policy constraints, motivates more PEV market shares than the monetary incentives only scenario, as well as the NEV credit-only policy scenario and the old dual credit policy scenario. When compared to the dual credit policy (2018–2020), two major types of adjustments in the dual credit policy (2021–2023) are changed: (a) the dual credit policy (2021–2023) mostly emphasizes the energy efficiency of BEVs, and the electricity consumption for a certain driving range (kW/100 km) and the battery’s energy capacity (kWh/kg) become more critical performance indicators to determine the value of NEV credit that each BEV can obtain; (b) unlike the dual credit policy (2018–2020), the dual credit policy (2021–2023) also encourages high fuel-efficiency ICE vehicles in the NEV credit rules. Therefore, because of more incentives on the ICEV-Low by the dual credit policy (2021–2023), the sales number of ICEV-Low in the reference scenario is the most among these five scenarios simulated.

The PEV market shares show much less than the quotas required by the dual-credit policy (2021–2023). This is because the quota defined by the NEV-credit rules refers to the ratio of PEV sales scores to ICEV sales scores, instead of the ratio of PEV sales to ICEV sales. When calculating the ratio, in the numerator, a BEV with long electric range could amplify the scores earned by PEV sales. In the denominator, a qualified hybrid electric vehicle can reduce the scores earned by ICEV sales. Accordingly, the rules bring the automakers to produce more BEVs with long electric range or more hybrids. Consequently, the market share of PEVs would be very likely smaller than the quota given by the dual-credit policy (2021–2023).

Figure 4 also clearly shows, with more strict requirements, the ratio of PEVs in the passenger vehicle market under the reference scenario increases more than it did under the old dual credit policy scenario. For example, comparing the PEV share under the old dual credit policy scenario, we found that the PEV share under the reference scenario increases to 11.7% in 2023 instead of 5.0% in the old dual credit policy scenario. At the same time, surprisingly, the total PEV share (11.7% in 2023) in the reference scenario was found to be smaller than it (13.1% in 2023) is in the CAFC credit-only policy scenario. Several reasons could possibly explain this: (a) the CAFC rules could incentivize the production of more PHEVs, which can be helpful for further reducing the industrial CAFC [

15]; (b) the positive NEV credits can be used for offsetting the negative CAFC credits in the dual credit policy, and thus the dual credit policy seems less stringent on improving zero-emissions vehicles (PEVs) compared to the CAFC credit-only rules. Meanwhile, because the dual credit policy (2021–2023) has more incentives for the ICEV-Low, the market shares and sales of ICEV-Low under the reference scenario are much more than they are in the CAFC credit-only policy scenario or other scenarios, as shown in

Table 2.

It was also found that the NEV credit-only policy scenario has less PEV sales. It means that the NEV credit rules create less policy incentives on PEV sales in the market than the CAFC credit rules. The major drive force of PEV growth is the CAFC credit rules in the dual credit policy (2021–2023). However, the NEV credit-only policy scenario creates a larger market share of ICEV-Low than the reference scenario or the CAFC credit-only policy scenario. In addition, the impacts of the scenarios—the old dual credit policy scenario, and the monetary incentives-only scenario—on the market sales are the same: their shares and sales in 2021–2023 are indifferent. It indicates that the requirements in the old dual credit policy have been relatively not strict enough to push forward the growth of PEV sales anymore in the current market. The market with the government subsidies and the vehicle license privilege policy (monetary incentives only scenario) could still motivate the PEV market to grow to 5.0% by 2023. Combined with the dual credit policy (2021–2023), the PEV market could grow to 11.7% by 2023.

4. Competitiveness of Plug-In Electric Vehicles in 2021–2023

The NEOCC can also reveal the possible PEV shares and sales by powertrain technologies.

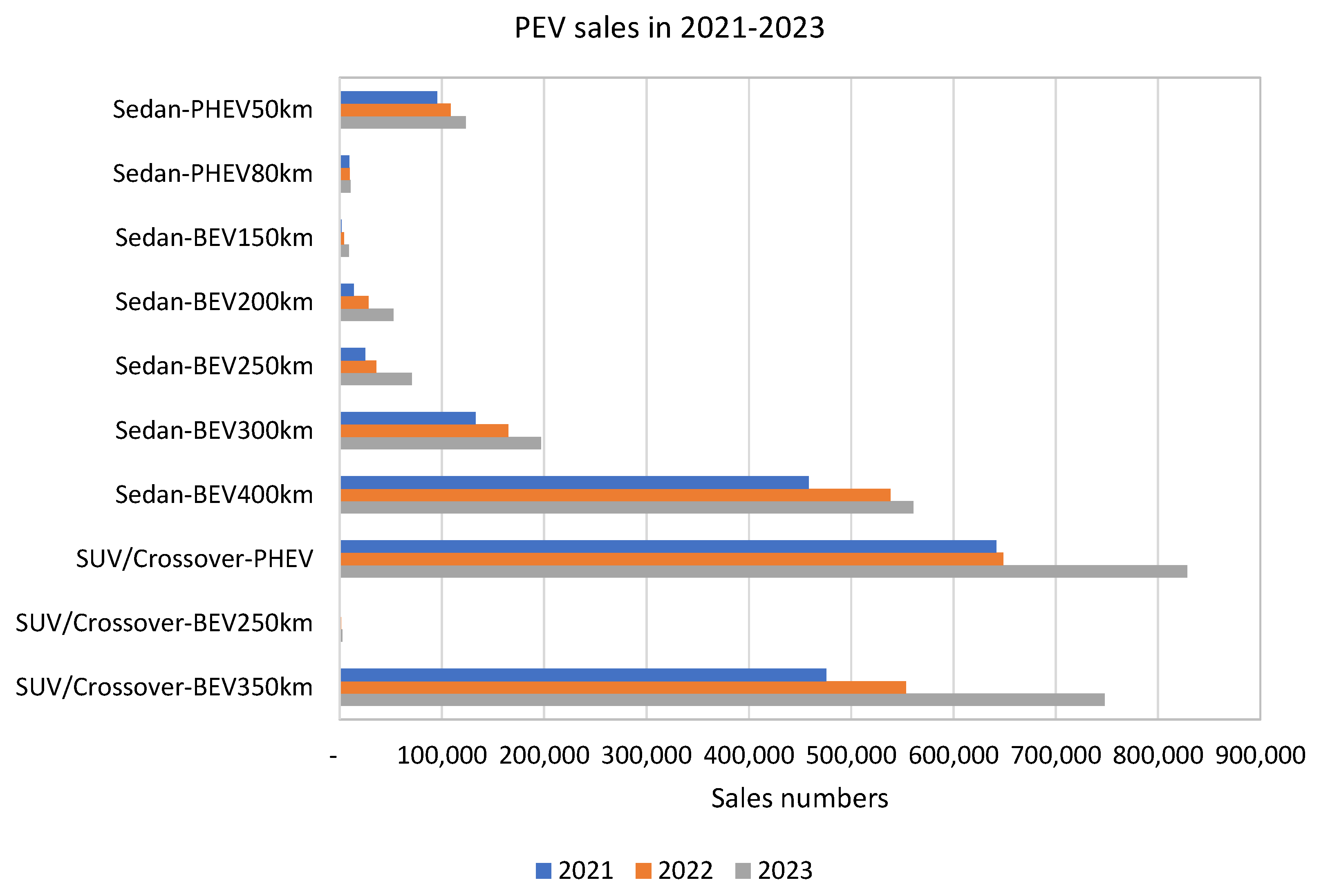

Figure 5 shows the market sales of PEV sales in 2021–2023 under the reference scenario.

Table A5 (

Appendix A) presents the projected market shares in PEVs for

Figure 5.

Table A6 (

Appendix A) presents the internal subsidies by industry for each technology so as to meet the requirements of dual-credit policy (2021–2023). This NEOCC model projects that the PEV sales could reach 1.286 million in 2020, which is very close to the 2020 passenger PEV sales—1.247 million published by the China Association of Automobile Manufacturers [

7]. Considering the downturn in the vehicle market in 2018–2019 and negative impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic, the projection could be harder to achieve. However, it is projected that the PEV sales could still reach reasonably promising numbers: 1.855 million in 2021, 2.095 million in 2022, and 2.603 million in 2023 if the sales trend continues as per the market in 2020. Among these new PEV sales, the BEVs are still more popular than the PHEVs. The BEVs with longer electric range (more than 300 km) are especially welcomed. There might be several reasons behind this: (a) the cost related to charging activities (BEV-300 km and BEV-400 km is better at saving this cost, as shown in

Figure 3), taking a nonnegligible amount in the total cost of ownership on the PEVs, and (b) both the dual credit policy (2021–2023) and the government subsidies are more clearly favorable when the BEVs have a longer electric range [

9]. However, on the other hand, it was found that 99% of the daily driving distances of a personal owned vehicle in China is no more than 112.0 km, which means that BEV-150 km could still meet most daily needs of personal vehicle drivers if the electric range anxiety is not considered [

19]. Thus, while BEVs with extended range could be used by the public-fleet drivers (such as taxis, or shared mobility), the BEVs with short electric range can still have their reasonable market space for the personal vehicle drivers. For example, the GM and SAIC’s Wuling released a car model—Hong Guang Mini EV with electric range at 120 or 170 km, which does not target on the government subsidies but aims to meet the driver’s basic travel patterns and the potential low-income buyers who are more sensitive to vehicle price [

20]. In the SUV/crossover segment, the PHEVs and the BEVs with extended range are more popular, most likely due to the SUV/crossover keeping aligned with the current market and people who want to buy an SUV/crossover being less sensitive to the vehicle price while having larger range anxiety.

At the same time, nearly 50% of PEVs could be SUVs/crossovers by 2023, as shown in

Figure 6. The plug-in hybrid SUVs/crossovers and the battery electric SUVs/crossovers with long electric range (≥350 km) could largely grow in the following several years. The PEV stocks by 2023 could be dominated by battery electric sedans with an electric range of 400 km or more, battery electric SUVs/crossovers with an electric range of 350 km or more, and plug-in hybrid electric SUVs/crossovers that take more than 70% of the market. In addition, it was found that the dual credit policy (2021–2023) encourages the BEVs with long electric range in the market more than the CAFC credit rules only, NEV credit rules only, and the dual credit policy (2018–2020). For example, in 2023, the total share of sedan-BEV 300 km, the sedan-BEV400 km, and the SUV/crossover–BEV350 km was found to take up more than 57% of the market under the reference scenario. This is higher than it was (41%) under the old dual credit policy scenario.

5. Conclusions

By adopting the vehicle policy analysis tool—NEOCC model, this study quantified the impacts of the dual credit policy (2021–2023) (official version released in June 2020) on the vehicle market in 2021–2023 in China. The impacts of several policy scenarios are compared, and the market dynamics in 2021–2023 under these scenarios are also projected. Major findings are concluded on the basis of the simulation results by the NEOCC model:

In general, the BEVs with a longer electric range often bring less cost on the charging-related activities. For example, by 2023, the sedan BEVs with electric range at 400 km were found to have the lowest cost of ownership related to the charging activities.

Owning a dedicated residential parking spot can largely reduce the cost related to charging activities; the cost-saving effectiveness of owning a parking spot is more prominent to the BEVs with a shorter electric range.

Compared to the CAFC credit rules only, the dual credit policy (2021–2023) seems less effective to incentivize the growth of PEV market shares. Meanwhile, the dual credit policy (2021–2023) can contribute more sales of hybrid electric vehicles in the market. For example, the sales of ICEV-Low could increase close to 0.91 million by 2023 under the reference scenario.

It is found that, compared to the CAFC credit-only policy scenario, the NEV credit-only policy scenario creates less motivations on the PEV growth in 2021–2023. Meanwhile, because of the increase of the NEV scores for hybrid electric vehicles, the projected sales of ICEV-Low are the highest among all the scenarios simulated. Therefore, policymakers should consider how to coordinate the relationship between the CAFC credit rules and the NEV credit rules for achieving their goals.

The impacts of the dual credit policy on the market becomes much more significant than the dual credit policy (2018–2020) and other policies such as government subsidy or the vehicle license privilege policy. Under the monetary incentives-only scenario, the market with the government subsidies and the vehicle license privilege policy could increase the PEV market to 5.0% by 2023. However, under the dual credit policy (2021–2023), the PEV market could grow to 11.7% by 2023.

Although the sedan BEVs with electric range at 150 km have also met most travel demands of personal vehicle drivers, the BEVs with short electric range are less favorable by the dual credit policy (2021–2023) and the government subsidies.

The BEVs with longer electric range could be more and more popular during 2021–2023. For example, by 2023, the sedan–BEV300 km, the sedan–BEV400 km, and the SUV/crossover–BEV350 km in total take more than 57% of the market in 2023 under the reference scenario, being higher (41%) than under the old dual credit policy scenario.

It is worth noting that these conclusions mentioned above are based on the premise that PEV sales will continuously grow up as was the case in 2016–2018. Considering that the vehicle market experienced a severe downturn during 2018 and 2019 and the longer-term uncertainties brought by the COVID-19 pandemic globally, we agree it is still an open question for researchers as to whether the electrification transition will continuously expand in this rapidly developing market. However, it is still meaningful to draw a general picture for the public, specifically for policymakers, in order to understand the possible future trend of the electric vehicle market in China under the government subsidies, the vehicle license privilege for PEVs, and the dual credit policy (2021–2023)—one of the most significant vehicle policies in recent years.

Rather than discussing which policy is more effective, with it all depending on what results the policymaker expects to have in the market, this study attempted to reveal the potential market evolution impacts by multiple vehicle policies, specifically the dual credit policy (2021–2023). Currently, some assumptions such as the projections of the fuel economy and battery cost are based on a review of recent literature, and some calculations are simplified for the data analysis. The market data needs close follow-ups and revisions as more is learnt. The analysis and the NEOCC model will be continuously updated and improved.