1. Introduction

With the evolution of communication technologies, the services supported by communication devices have expanded from early text and voice to today’s video streaming and immersive virtual reality. This expansion has been accompanied by increasingly stringent performance requirements. From the perspective of resource allocation, numerous algorithms have been proposed to meet diverse performance objectives such as throughput, latency, and fairness. Among the most widely recognized are the Best-channel quality indicator (CQI) algorithm [

1], in which each user equipment (UE) competes for transmission resources based on its own CQI and achieves high throughput; the maximum-largest weighted delay first (M-LWDF) algorithm [

2], which prioritizes packets nearing expiration to reduce packet loss; and the proportional fair (PF) algorithm [

2], which selects the UE with the largest ratio of instantaneous achievable rate to historical average throughput, ensuring that all UEs have opportunities to access transmission resources.

With the advent of fourth-generation (4G) mobile networks, advances extended beyond resource allocation algorithms. For example, device-to-device (D2D) communication [

3] enables direct transmission between UEs without traversing a base station (BS) and allows certain UEs to relay data on behalf of others. Similarly, orthogonal frequency division multiplexing (OFDM) [

4] exploits orthogonality to achieve significantly higher spectral efficiency compared with other modulation techniques, thereby supporting higher data rates.

With the transition to fifth-generation (5G) mobile networks, expectations rose for further increases in data rates, along with improvements in latency, energy efficiency, and service coverage. The Third Generation Partnership Project (3GPP) standards body classified services into three categories: ultra-reliable low-latency communications (URLLC), enhanced mobile broadband (eMBB), and massive machine-type communications (mMTC). Their key performance requirements are summarized in

Table 1. To meet these demands, researchers have proposed techniques such as puncturing, which allows latency-sensitive packets to preempt ongoing transmissions [

5], and power-domain non-orthogonal multiple access (NOMA) [

6], which enables multiple packets to be transmitted simultaneously over the same frequency band at different power levels, thereby enhancing 5G performance.

Over the past decade, the proliferation of mobile devices and the exponential growth of mobile traffic have driven remarkable advances in wireless communications and networking. However, the computational demands of emerging services often exceed the processing capabilities of mobile devices. Although device processing power has steadily improved, it remains limited compared with servers. To address this gap, researchers proposed mobile cloud computing (MCC) [

10], in which tasks are offloaded to remote cloud servers. Yet, due to the relatively long transmission distance between UEs and MCC servers, MCC alone is insufficient to satisfy 5G requirements. Consequently, mobile edge computing (MEC) emerged as a key 5G technology [

11]. By deploying small servers in close proximity to BSs, MEC enables data to be processed nearer to end users, potentially improving both latency and throughput.

Meanwhile, spectrum scarcity became increasingly critical. By 4G, most conventional frequency bands were already occupied, and 5G introduced millimeter-wave bands to expand capacity. Although millimeter waves provide higher data rates, their rapid attenuation and poor penetration reduce BS coverage compared with 4G and necessitate costly infrastructure densification. In response, sixth-generation (6G) research has proposed solutions such as reconfigurable intelligent surfaces (RIS) [

12] and low-earth-orbit satellite communications [

13]. RIS can enhance received signals and reflect them toward intended directions, potentially improving link quality, while satellites may help extend coverage to broader areas.

As performance requirements continue to escalate, MEC plays a pivotal role in reducing latency and increasing throughput. However, most existing MEC studies assume that each UE is served by a single MEC server, which can lead to overload when traffic is concentrated, thereby degrading both transmission and computation efficiency. Furthermore, integrating heterogeneous enabling technologies (e.g., D2D, RIS, MEC, and 6G) with diverse application perspectives (e.g., user mobility, traffic characteristics, and service heterogeneity) remains an open research challenge. In the context of 6G, designing efficient resource allocation and scheduling algorithms that jointly exploit D2D and RIS to enhance MEC networks while balancing multiple performance dimensions is a pressing issue.

To this end, we propose a framework that explicitly follows the uplink–computation–downlink process. Each UE initially offloads packets to the MEC server associated with its serving BS. On the uplink, a helper-assisted D2D scheme is introduced to assist transmission. Unlike conventional D2D without helper nodes, our scheme leverages idle UEs as relays to overcome UE power limitations and ensure more reliable connectivity. The BS then determines, based on service type and MEC load, whether to partition and redistribute packets to a selected neighboring MEC server for cooperative processing. On the downlink, RIS-assisted transmission and placement strategies are employed to return results efficiently to UEs. Building on these technologies, we design a transmission-path selection algorithm with joint computation and communication resource allocation, aiming to improve the effective packet-delivery success percentage, which intuitively represents the probability that packets are successfully delivered within the required latency bound.

The main contributions of this paper can be summarized as follows:

Transmission-path selection algorithm: We develop a transmission-path selection algorithm that jointly optimizes computation and communication resource allocation in 6G MEC networks enhanced by helper-assisted D2D, MEC cooperation, and RIS assistance. In the uplink, only one transmission path is activated at a time to ensure efficient resource utilization, whereas in the downlink, results can be flexibly returned through multiple paths—for example, partly from the local MEC and partly from a selected neighboring MEC via RIS. The algorithm is implemented under the modified maximum rate (MR) and PF scheduling policies and is designed to maximize the effective packet-delivery success percentage under stringent latency constraints.

Helper-assisted D2D uplink: We introduce a helper-assisted D2D scheme that leverages idle UEs as relays in the uplink. By constraining the broadcast power of BSs and helpers, reliable channel conditions are maintained between helpers, BSs, and UEs, thereby mitigating UE power limitations and improving uplink reliability.

Packet-partitioning cooperative MEC offloading: We design a cooperative offloading mechanism in which a packet initially offloaded to the local MEC may be partitioned and distributed to a selected neighboring MEC for joint computation. To limit complexity, each packet is processed by at most two MECs—the local MEC and one selected neighboring MEC.

RIS-assisted downlink design: We exploit the signal-enhancement capability of RIS to extend BS coverage beyond its conventional range. By carefully designing RIS placement and transmission strategies, the downlink coverage can be expanded and unnecessary handovers may be reduced.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows.

Section 2 reviews related work on packet scheduling, D2D/NOMA integration, heterogeneous 5G service scheduling, MEC optimization, and RIS-assisted systems.

Section 3 introduces the system model and formulates the problem as a joint optimization across uplink path selection, MEC cooperation, and downlink transmission, subject to service-specific latency constraints.

Section 4 presents the transmission-path selection algorithm, designed as a heuristic approximation to this joint optimization problem, integrating helper-assisted D2D uplink, MEC cooperation, and RIS-assisted downlink, and providing a formal complexity and scalability analysis.

Section 5 reports simulation results, performance evaluation, and sensitivity analyses, highlighting the effectiveness and robustness of the proposed algorithm under diverse parameter settings. Finally,

Section 6 concludes the paper, discusses limitations, and outlines potential directions for future research.

3. System Model

3.1. System Environment

We consider a 6G network comprising a set of BSs, denoted by

(indexed by

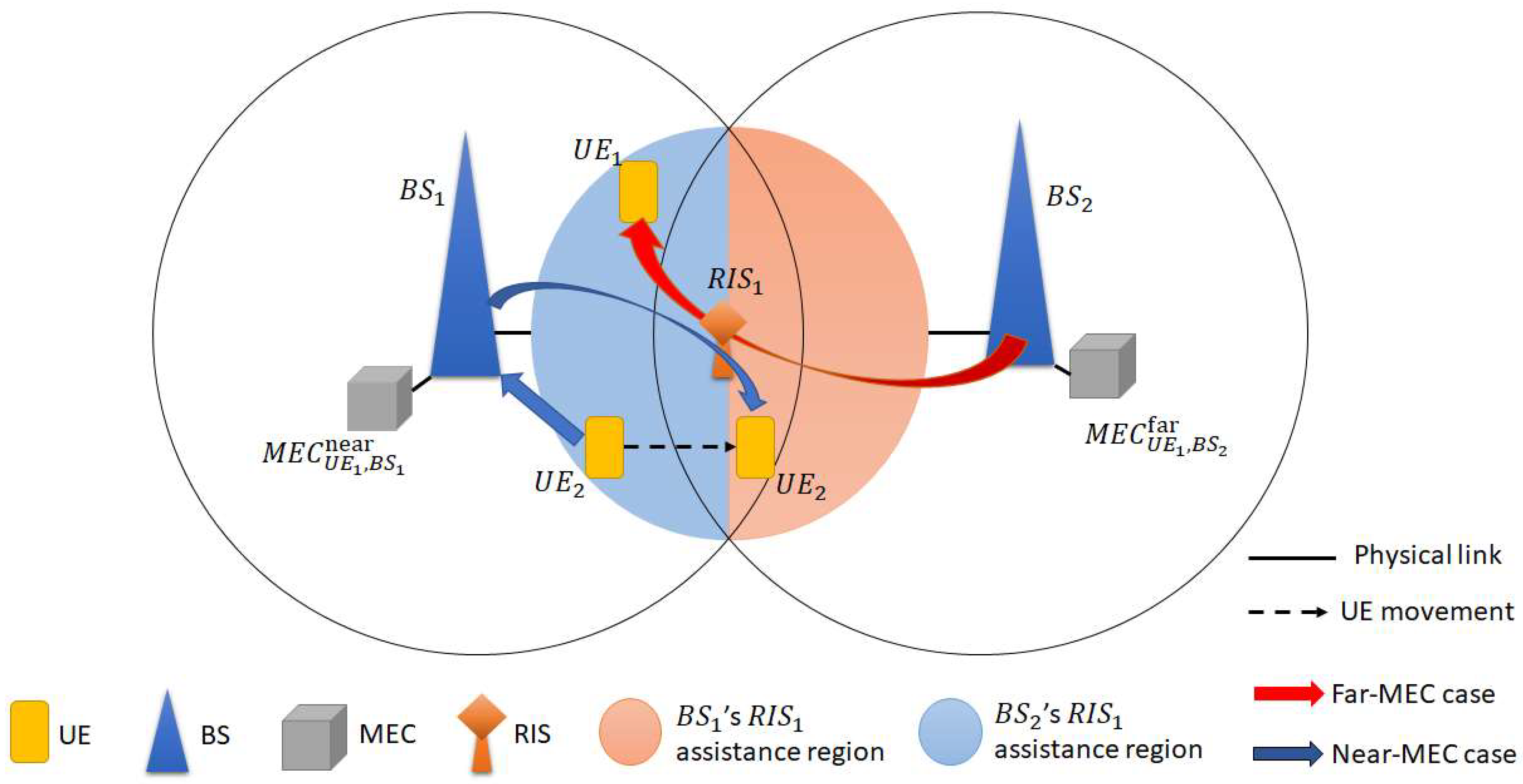

). As illustrated in

Figure 1, each BS defines a circular coverage area, and six adjacent BSs are placed around it at equal angular spacing of 60 degrees, forming the surrounding topology. All BSs are interconnected via reliable wired links, so inter-BS transmission errors can be neglected. Each BS is co-located with an MEC server; since the MEC is deployed adjacent to the BS, the transmission delay between them is negligible. Adjacent BS coverage areas overlap, and RISs are deployed at the boundaries of these overlapping regions. To capture this deployment formally, we consider a set of RISs, denoted by

(indexed by

), with each BS associated with six RIS panels. For tractability, each RIS is modeled as a sectorized reflector composed of

equal-angle facets. The default configuration sets

. Here, “facets” refer to angular sectors in the coverage model rather than physical panels. While a physical RIS panel typically covers approximately 180° in the front half-space, our tractable model adopts a 360° sectorized approximation to simplify analysis at BS coverage boundaries. A UE is eligible for RIS-assisted reflection only if its incident angle falls within the field of view of at least one facet. To capture the directional nature of RIS beamforming, RIS gain is assumed to scale with facet count

: narrower facets yield higher directivity. For calibration, RIS gain is set to 20 dB at

facets, serving as an idealized reference point rather than a fixed empirical standard. Reported RIS prototypes typically achieve 5–15 dB gain, with some large-scale designs occasionally exceeding 20 dB in specific indoor scenarios [

56,

57,

58]. The detailed scaling rule and the sensitivity/robustness to alternative gain values are analyzed in

Section 5.3. This abstraction maps element-level beamforming benefits into a tractable facet-based representation, reflecting the effective gain of phase optimization without explicitly modeling per-element structures. For clarity, each RIS is assumed to form a single main beam directed toward the selected facet, with boundary angles treated as inside by convention. This single-beam assumption ensures tractability while preserving the directional nature of RIS reflection; extending to multi-beam RIS with energy-splitting models is left for future work. In practice, BSs and RISs employ directional antennas to enable beamforming, and future extensions may incorporate antenna patterns for added realism. We further consider a set of UEs, denoted by

(indexed by

), across the network. Both UEs and BSs are equipped with transmission and reception buffers. Specifically, the transmission and reception buffer sizes of

are denoted by

and

, respectively. Similarly, the transmission and reception buffer sizes of

are denoted by

and

, respectively. Each UE generates multiple packets per second of identical size and service type, where the probability that

generates a packet of service type

is denoted by

, with

, where

. Uplink and downlink transmissions are allocated to orthogonal channels, which do not interfere with each other and both support multi-user access. Let

and

denote the transmit powers of

and

, respectively.

In designing the relay strategy, different considerations are applied to uplink and downlink. For downlink transmission, the BS has sufficient transmit power, and RIS can help extend the BS’s coverage area, potentially supporting UEs located near or slightly outside the original cell boundary. Consistent with the single-beam RIS model introduced earlier, downlink employs RIS-only assistance, with RIS panels strategically placed at coverage edges to maximize service extension. In contrast, uplink transmission is constrained by the limited transmit power of UEs. Even with RIS gain, poor channel conditions cannot be fully compensated. Therefore, RIS is not employed in uplink due to UE power constraints, as discussed above; instead, a helper-assisted D2D scheme is introduced to provide alternative, higher-quality transmission paths. Consequently, uplink employs the helper-assisted D2D scheme, while downlink relies solely on RIS assistance.

To illustrate the operation of this framework, we present two representative cases, as depicted in

Figure 1. In the first case,

adopts the helper-assisted D2D scheme in the uplink, forwarding its packet to a helper UE (

), which then relays the packet to its serving BS (

). Upon reception,

partitions the packet: one portion is processed locally at

’s MEC and returned directly to

, while the other portion is offloaded to the neighboring

’s MEC for computation and subsequently returned to

via

. Consistent with the single-beam RIS model introduced earlier,

forms a single directed beam toward

, which can help extend

’s effective coverage for the downlink transmission. In the second case,

transmits its packet directly to

without D2D assistance. After computation at

’s MEC, the result is delivered back to

, where

employs

for the downlink transmission.

similarly operates under the facet-based abstraction, forming one main beam toward

, in line with the tractable RIS design described in this section.

3.2. Helper-Assisted D2D Scheme

In this subsection, we design a helper-assisted D2D scheme that offers UEs an alternative uplink transmission option in addition to conventional direct communication. At the beginning of each scheduling period, denoted as , the BS broadcasts a signal to identify UEs that can serve as helpers. A UE that successfully receives this signal, is idle (i.e., has no transmission demand), and has a mobility speed below the threshold becomes eligible to act as a helper. The set of such UEs is denoted as helpers (set , indexed by ).

To ensure that helpers remain close to the BS and maintain favorable channel conditions, the BS sets its broadcast power to , where is the maximum transmit power of a UE, and denotes a power scaling factor indicating the fraction of used for BS broadcasting. Once a UE becomes a helper, it broadcasts a signal with the same power, enabling UEs within its coverage to recognize it as a helper. At this stage, each with transmission demand computes the time required for direct communication with its serving , as well as the time required when using the helper-assisted D2D transmission. If no helper is available, this time is set to ∞.

Through signaling interactions with

,

can estimate the channel condition and calculate the transmission time for conventional communication as

where

Here,

denotes the uplink payload size of service type

, and

represents the system bandwidth allocated for uplink transmission, and

and

respectively denote the SINR observed at

and the corresponding data rate when

directly transmits the

-th packet of service type

to

. Equations (1) and (2) follow the conventional transmission time definition [

59] and the Shannon capacity formulation [

60], respectively. It should be noted that this formulation is a simplified representation compared with full 5G system-level models. This deliberate choice ensures tractability and provides a common foundation for evaluating diverse transmission paths. Specifically, helper-assisted D2D transmission in the uplink, MEC offloading during computation, and RIS-assisted reflection in the downlink each influence these quantities by altering payload distribution or channel conditions, thereby influencing the modeled latency performance in the proposed 6G MEC framework. For helper-assisted D2D transmission, the total delay consists of two segments: from

to

, and from

to

. The transmission time from

to

is

where

Here,

and

respectively denote the SINR observed at

and the corresponding data rate when

transmits the

-th packet of service type

destined for

via

. The channel condition of this segment can be estimated by

from the broadcast signal of

. Equations (3) and (4) are consistent with (1) and (2), respectively [

59,

60]. The transmission time from

to

is

where

Here,

and

respectively denote the SINR observed at

and the corresponding data rate when

forwards the

-th packet of service type

, originally transmitted from

, to

. Since helpers are selected by the BS, each

is assumed to be aware of the channel condition to its serving

. Equations (5) and (6) are consistent with (1) and (2), respectively [

59,

60].

Subsequently, selects its uplink transmission mode based on the shorter delay:

then

adopts conventional direct communication.

then

competes for the corresponding

to assist its uplink transmission. The pairing between requesting UEs and helpers is established through the request-to-send (RTS)/clear-to-send (CTS) handshake mechanism in wireless collision-avoidance protocols. UEs that fail in the contention revert to conventional direct communication. Specifically, within a scheduling period, once a helper is successfully paired with a UE, it cannot be selected by other UEs. After completing the transmission for that UE, the helper loses its eligibility. If a helper is not selected by any UE until the end of the scheduling period, it stops broadcasting and relinquishes its helper status. The signaling overhead associated with helper discovery, contention (RTS/CTS handshake), and related control exchanges is not explicitly modeled in this subsection; its treatment is specified later in the performance evaluation setup (

Section 5.1). In the default setting, these overheads are assumed to be zero to provide a consistent basis for comparing diverse transmission paths, while the impact of non-zero overheads is examined in the sensitivity analysis (

Section 5.4) to validate the robustness of the proposed framework.

3.3. MEC Selection and Proportional Allocation

Although MEC servers provide a certain level of data processing capability, they may become overloaded when traffic is excessively high. To address this issue, we propose a cooperative MEC offloading mechanism that allows nearby MECs to collaborate. Each packet is processed by at most two MECs to reduce computational complexity. Specifically, when a UE offloads a packet to its local MEC, part of the packet may be further distributed to a nearby selected MEC depending on the load status and the service type. If the environment contains only one BS (and thus only one MEC), the distribution mechanism is not triggered. For clarity in subsequent descriptions, each BS is regarded as equivalent to its corresponding MEC.

To accurately capture the computation demand associated with different service-type packet sizes and the sub-packet structure introduced by packet partitioning, the instantaneous load of

, denoted as

, is defined as

Here,

denotes the set of all packets or sub-packets of service type

currently residing at

;

represents the computation demand (in million instructions (MI)) of the

-th (sub-)packet of service type

; and

is the computation capacity (in million instructions per second (MIPS)) of

. The metric

thus reflects the fraction of MEC resources consumed within one scheduling period. In this work, we classify the load level as medium when

, and as high when

. For clarity, the MEC server associated with the BS currently serving

is denoted as

.

In a multi-BS environment, when transmits a packet to and offloads it to , three cases are considered:

High load at the local MEC: If is determined to be under high load, all packets in the transmission buffer of are discarded (discarded during preliminary simulations before actual transmission).

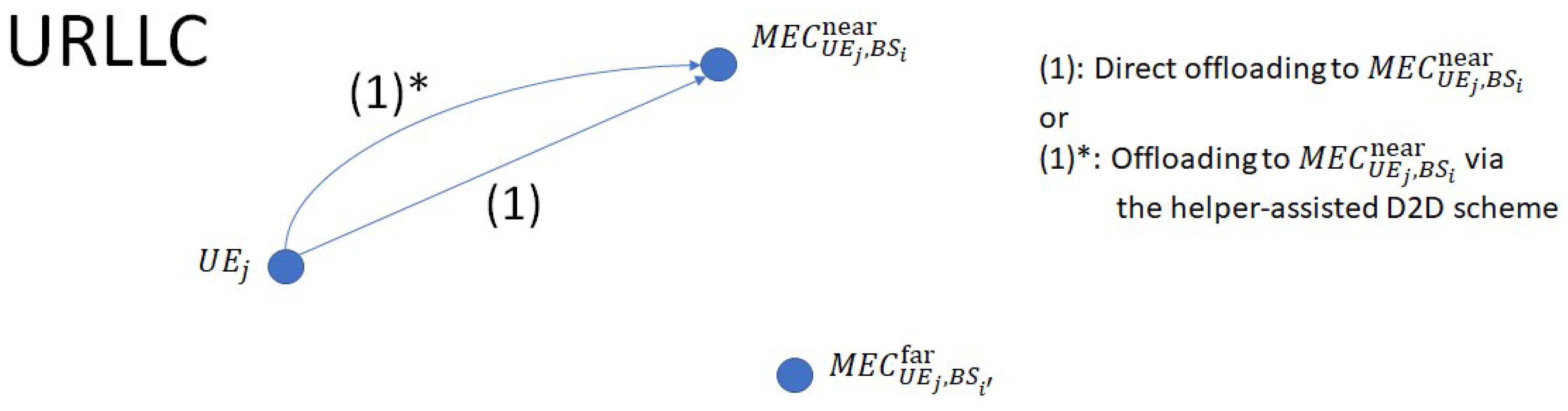

Medium load at the local MEC with URLLC packets: If

is under medium load and the packet belongs to the URLLC service type, the packet is processed directly at

(see

Figure 2).

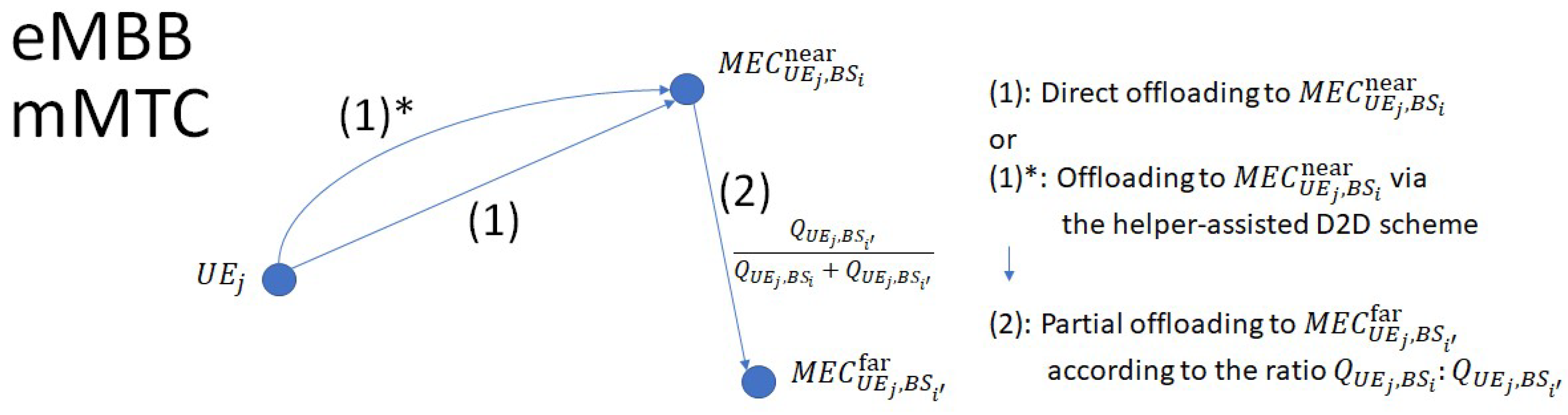

Medium load at the local MEC with eMBB or mMTC packets: If

is under medium load and the packet belongs to eMBB or mMTC, packet splitting is adopted to balance computational load between MECs and cope with latency constraints. Let

and

denote the CQIs perceived by

from

and from

, respectively. The packet is divided into two parts with ratio

(see

Figure 3). The first part is processed at

, while the second part is offloaded to the MEC corresponding to the selected neighboring BS, denoted as

. The selection of

follows the descending order of the

values among nearby BSs. The BS with the highest CQI is selected first; if its corresponding MEC is under medium- or high-load, the next BS in descending CQI order is then considered. If this MEC is also under medium or high load, all packets in the transmission buffer of

are discarded (discarded during preliminary simulations before actual transmission). Let

denote the computation demand (in MI) of a full packet of service type

. Let

and

denote the computation demands (in MI) of the near and far portions of the

-th packet generated by

for service type

, respectively. When packet splitting is applied, the computation demands of the near and far sub-packets are determined proportionally according to the splitting ratio

. Specifically,

and

are given by

and

, respectively, which satisfy

.

In the case where only one BS exists in the environment, only is available. If it is under high load, all packets in the buffer of are discarded (discarded during preliminary simulations). In all other cases, packets are processed directly at .

For clarity in subsequent descriptions, packets processed at are denoted as , while packets processed at are denoted as .

3.4. RIS-Assisted Transmission and Deployment Design

Figure 4 illustrates the RIS-assisted transmission scenario. To establish a clear basis for the subsequent discussion, we introduce the following definition:

Assistance region: The outer semicircular area supported by the RIS of

. For instance, in

Figure 4, the assistance region of

corresponds to the light-orange sector, while that of

corresponds to the light-blue sector.

We consider two representative cases where RIS is employed to assist transmission:

Far-MEC case: For a packet labeled that has been processed by , if lies within the assistance region of associated with , then forwards the processed packet to via .

Near-MEC case: For a packet labeled that has been processed by , if lies within the assistance region of associated with , then delivers the processed packet to through .

As an example, consider

Figure 4. In the first case, once

completes the processing of packet

, if

detects that

is located in the assistance region of

, then

forwards the packet to

through

, which may help improve transmission efficiency. In the second case, after

processes packet

, if

moves into the assistance region of

associated with

, then

transmits the packet to

through

. In this case, the RIS can help enhance the received signal strength at

, helping it to remain above the handover threshold and potentially reducing unnecessary handovers and the additional latency they incur.

To maximize RIS effectiveness, we design its placement strategy by explicitly accounting for both transmission scenarios. In the far-MEC case, RIS units are best deployed at the cell edge to extend coverage, whereas in the near-MEC case, they should be positioned at the center of the overlapping region to reinforce signals and reduce handovers. A joint placement strategy at the overlap center thus addresses both cases simultaneously, which can help improve overall system performance.

Facet selection in downlink transmission follows a geometric rule: the facet whose angular sector contains the incident angle of the UE associated with the packet currently scheduled for downlink transmission is selected as the active reflection path. When multiple UEs are located in different facets simultaneously, only the facet corresponding to the scheduled UE is activated, while other UEs are not assisted during that transmission instance, consistent with the single-beam assumption. When multiple UEs are located within the same facet, only the UE selected under the downlink scheduling policy is assisted by RIS in that instance, while other UEs in the same facet are not served until they are scheduled in subsequent transmissions. In each downlink scheduling instance, the RIS forms only one directed beam toward the scheduled UE; beam switching within the same instance is not considered, to preserve tractability and avoid switching overhead. For clarity, RIS operation in both far-MEC and near-MEC cases follows the tractable facet-based model introduced in

Section 3.1, ensuring consistency with the single-beam assumption and avoiding multi-beam energy splitting or inter-beam interference. The placement strategy described above refines the boundary deployment introduced in

Section 3.1 by distinguishing far-MEC and near-MEC cases. The transmission procedures defined here are explicitly quantified in

Section 3.5 through the uplink and downlink delay formulas.

3.5. Definition of Uplink and Downlink Transmission Procedures

3.5.1. Uplink Transmission Procedure

In our design, uplink transmission can be realized through two communication modes: Uplink Mode A (conventional/direct transmission) or Uplink Mode B (helper-assisted D2D transmission).

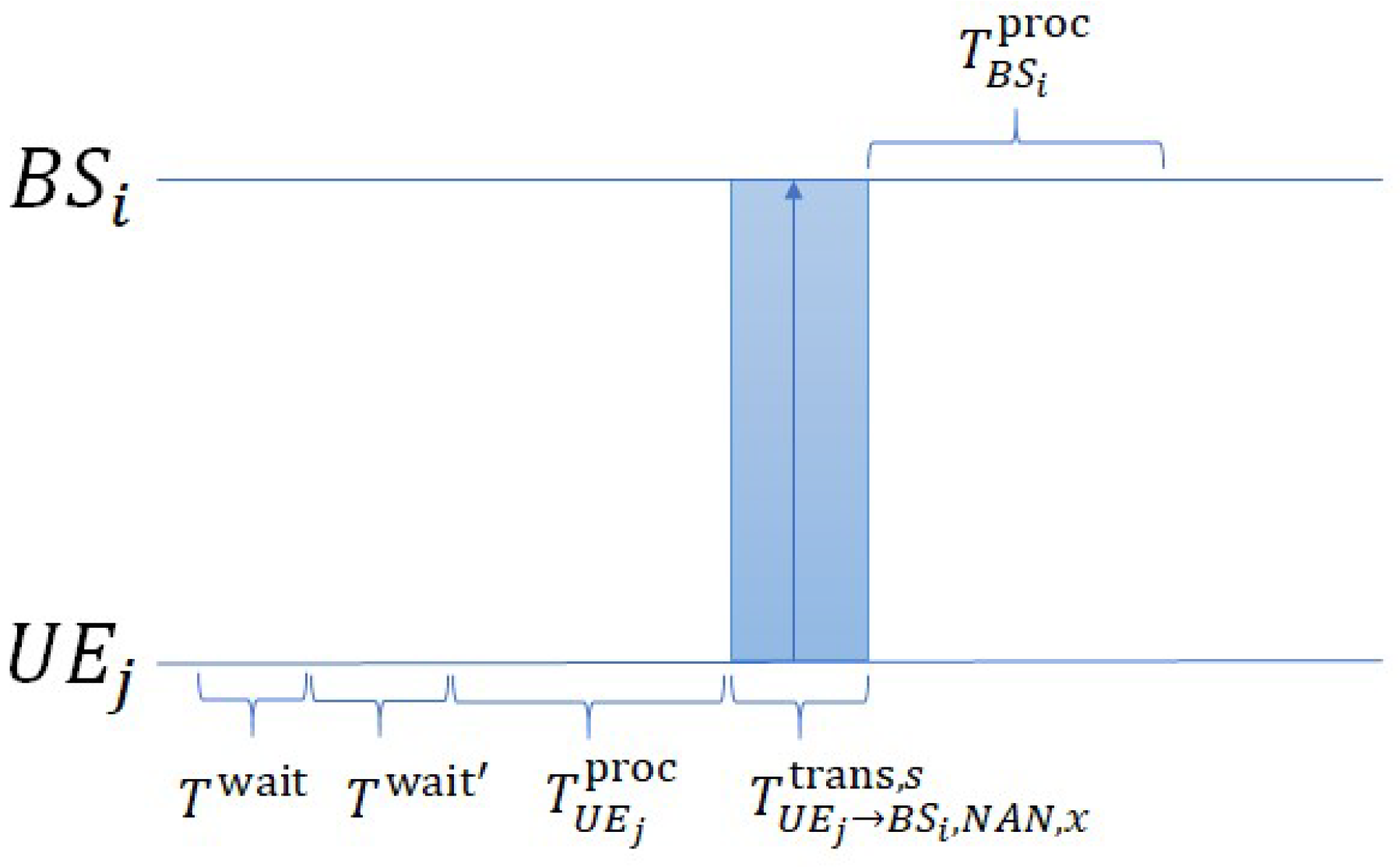

Uplink Mode A (conventional/direct transmission): If

adopts Uplink Mode A, the packet flow follows the procedure illustrated in

Figure 5. The delay is composed of four stages: (1) Scheduling delay:

, where

denotes the random waiting time for the packet in the transmission buffer of

to first contend for channel resources from

, and

denotes the additional waiting time until the packet successfully obtains channel resources after the first contention. Here,

is the number of contention attempts made by

before successfully acquiring channel resources from

. (2) Processing time at

:

. (3) Direct transmission time from

to

:

. (4) Processing time at

:

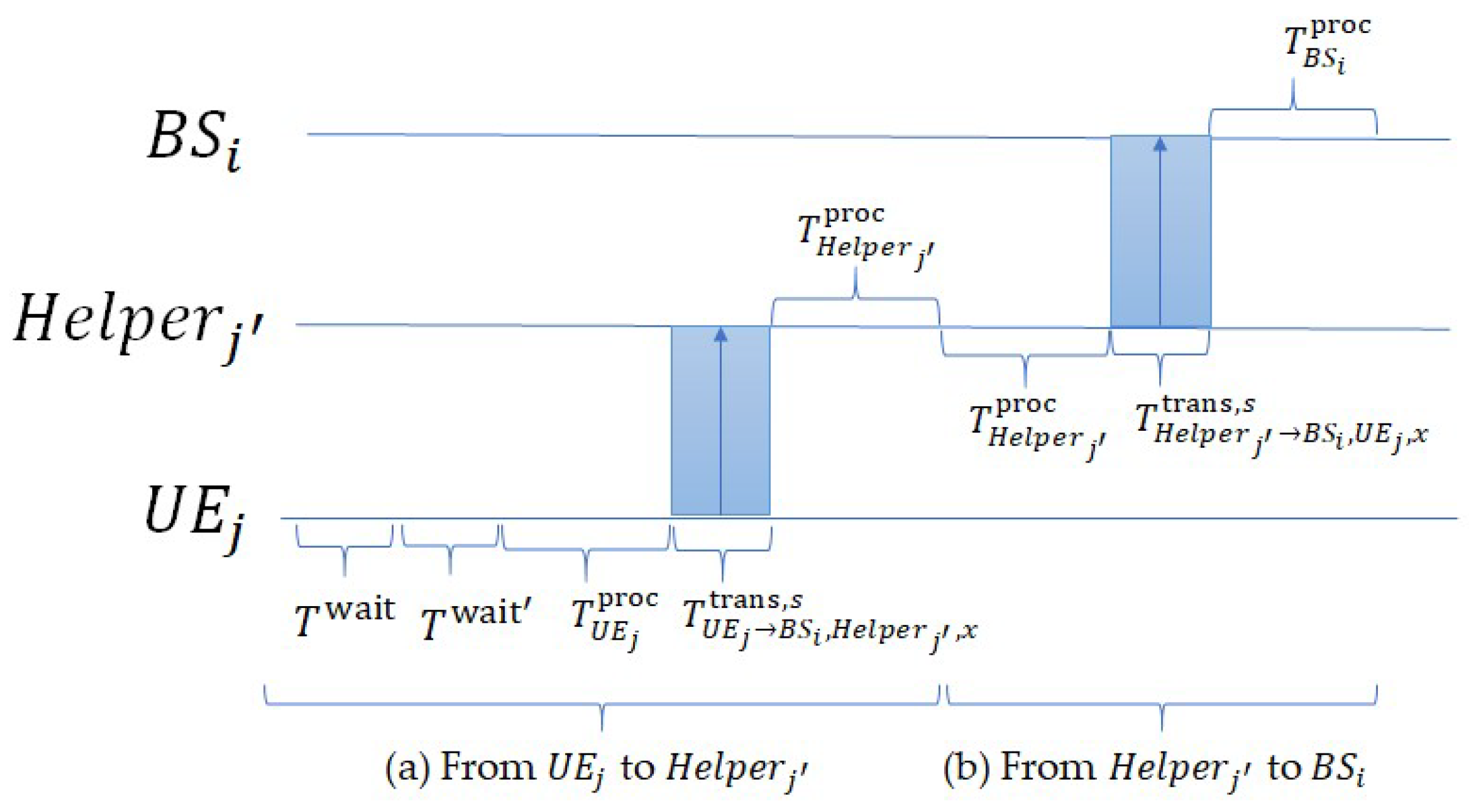

Uplink Mode B (helper-assisted D2D transmission): If

employs Uplink Mode B, the packet flow follows the procedure in

Figure 6 and is divided into two paths: (a) from

to its helper

, and (b) from

to

. For path (a), the delay is composed of four stages: (1) Scheduling delay:

. (2) Processing time at

:

. (3) Transmission time from

to

:

. (4) Processing time at

:

. For path (b), the delay is composed of three stages: (1) Processing time at

:

. (2) Transmission time from

to

:

. (3) Processing time at

:

.

Accordingly, the total uplink delay is expressed as:

3.5.2. Downlink Transmission Procedure

Downlink transmission can be realized through four modes: Downlink Mode A (local BS direct transmission), Downlink Mode B (local BS transmission via RIS), Downlink Mode C (non-local BS transmission without RIS), or Downlink Mode D (non-local BS transmission via RIS).

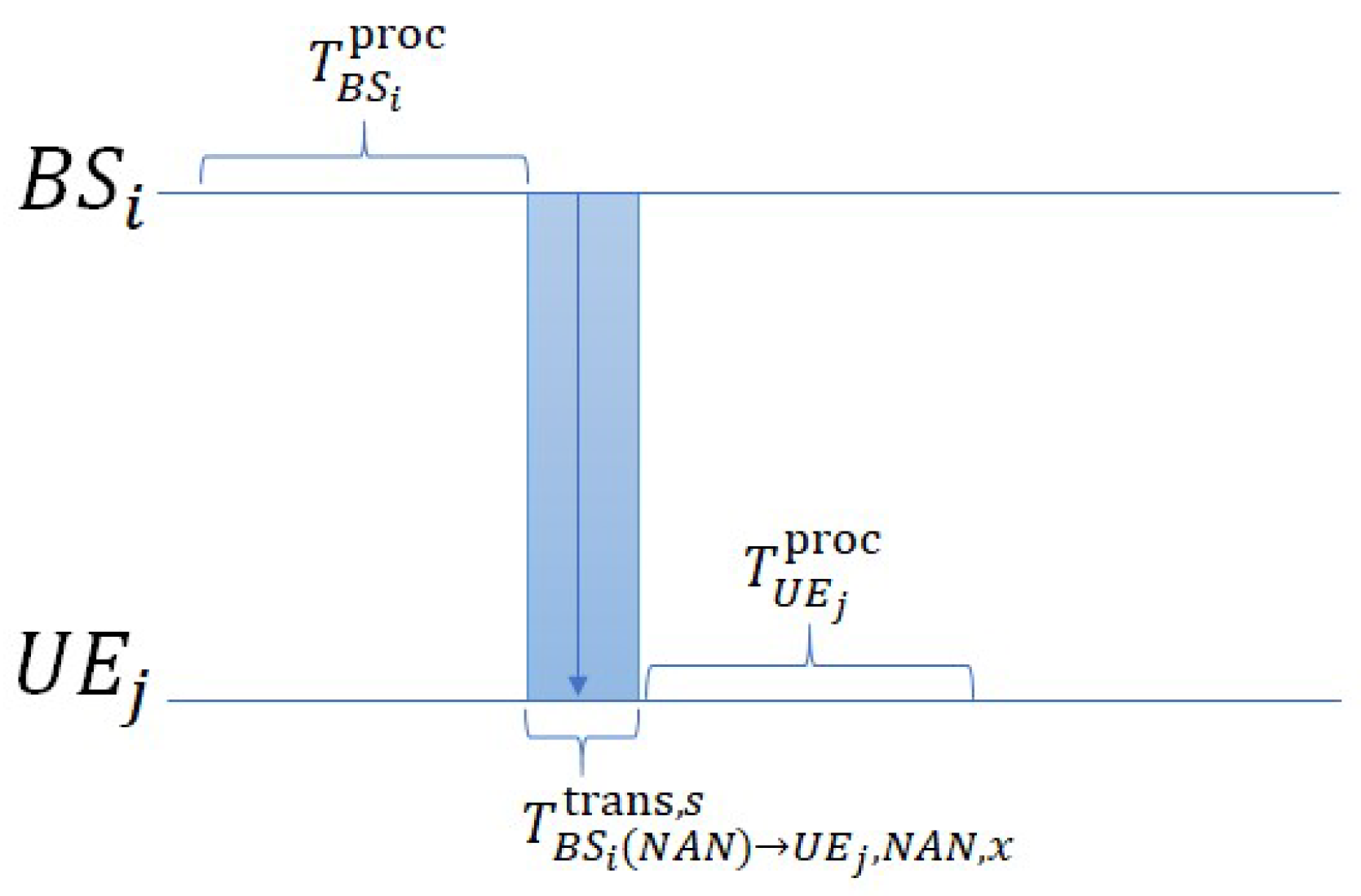

Downlink Mode A (local BS direct transmission): If

adopts Downlink Mode A, the packet flow follows the procedure illustrated in

Figure 7. The delay is composed of three stages: (1) Processing time at

:

. (2) Transmission time directly from

to

:

. (3) Processing time at

:

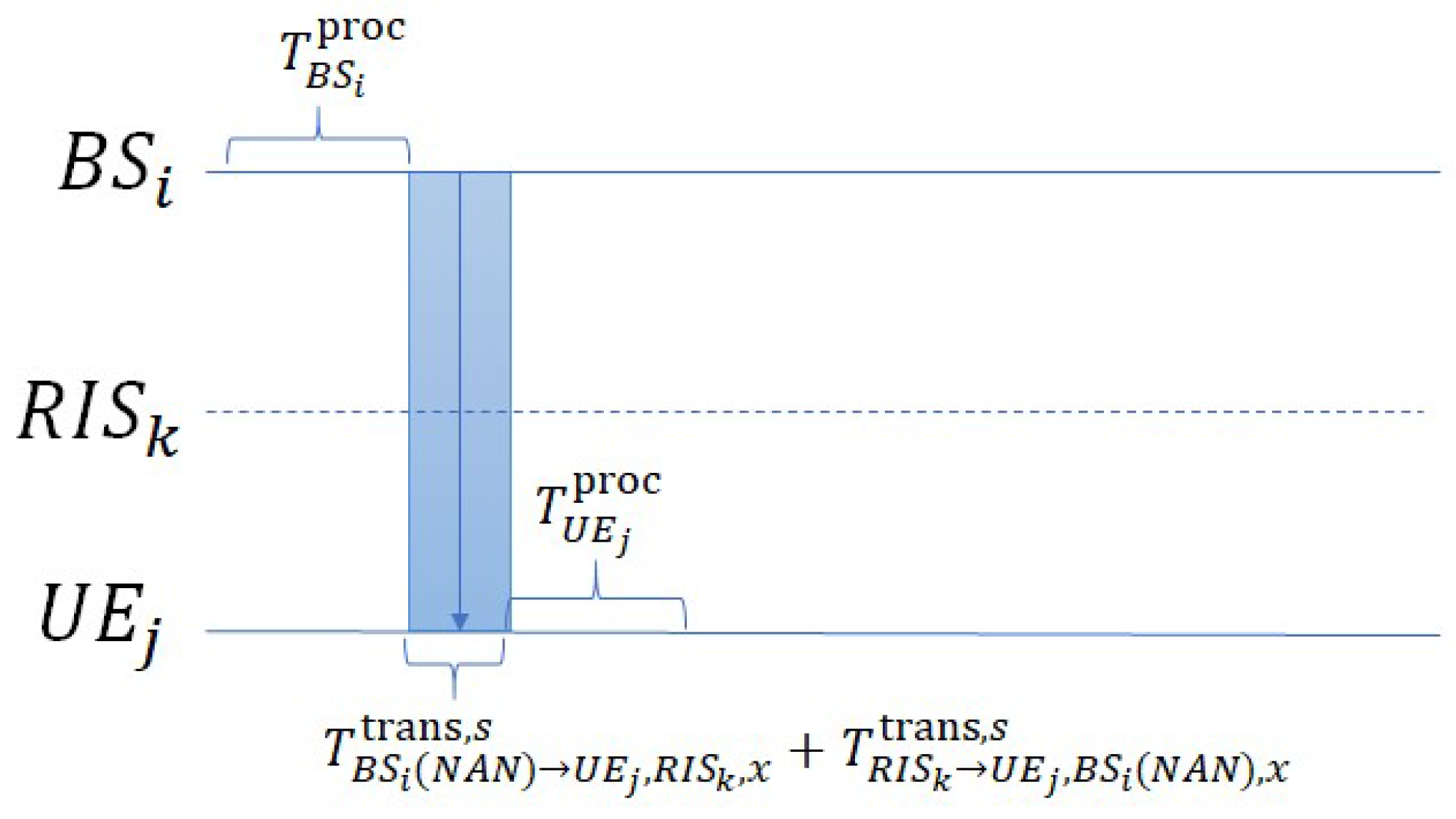

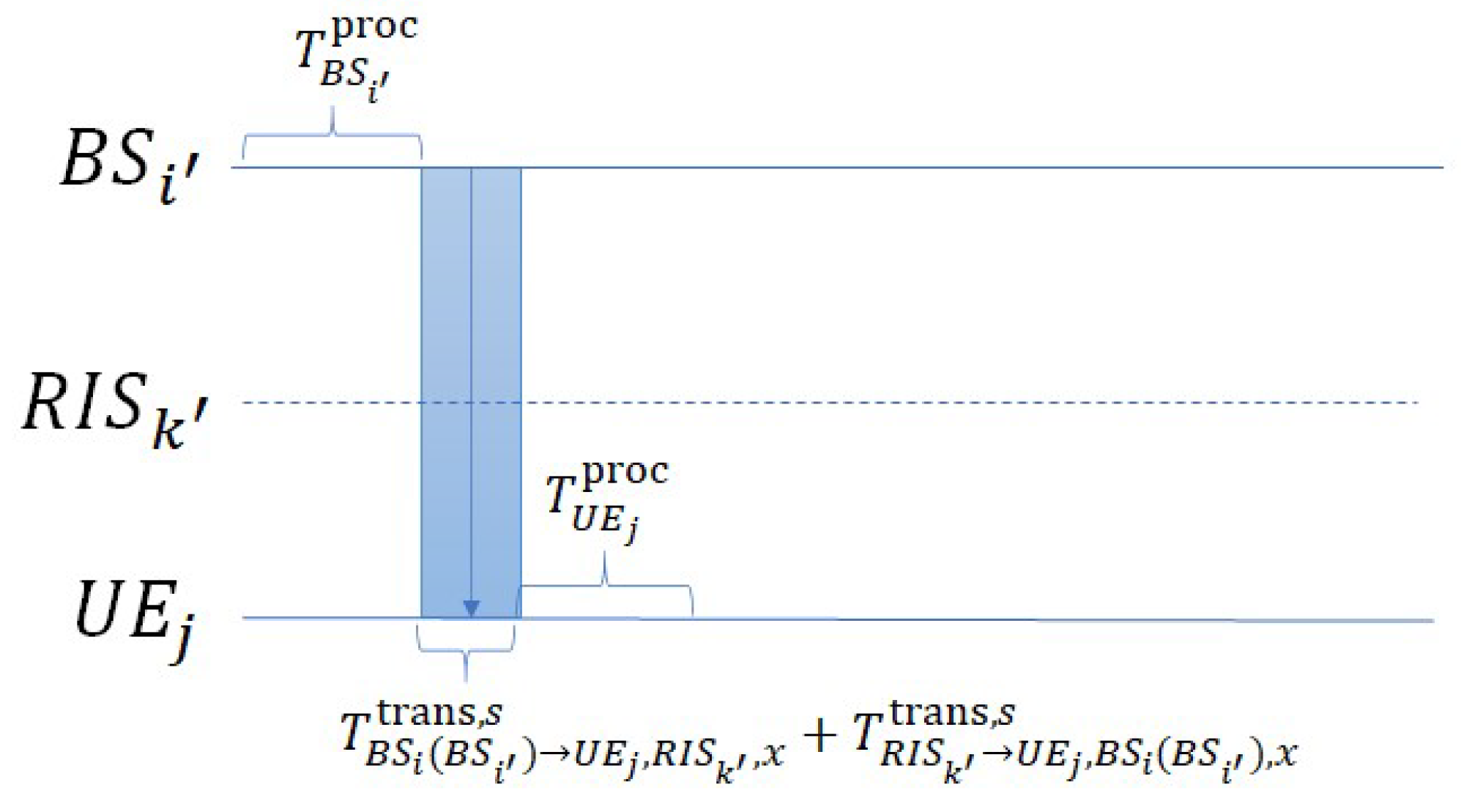

Downlink Mode B (local BS transmission via RIS): If

adopts Downlink Mode B, the packet flow follows

Figure 8. The delay is composed of three stages: (1) Processing time at

:

. (2) Transmission time from

to

via

:

. (3) Processing time at

:

.

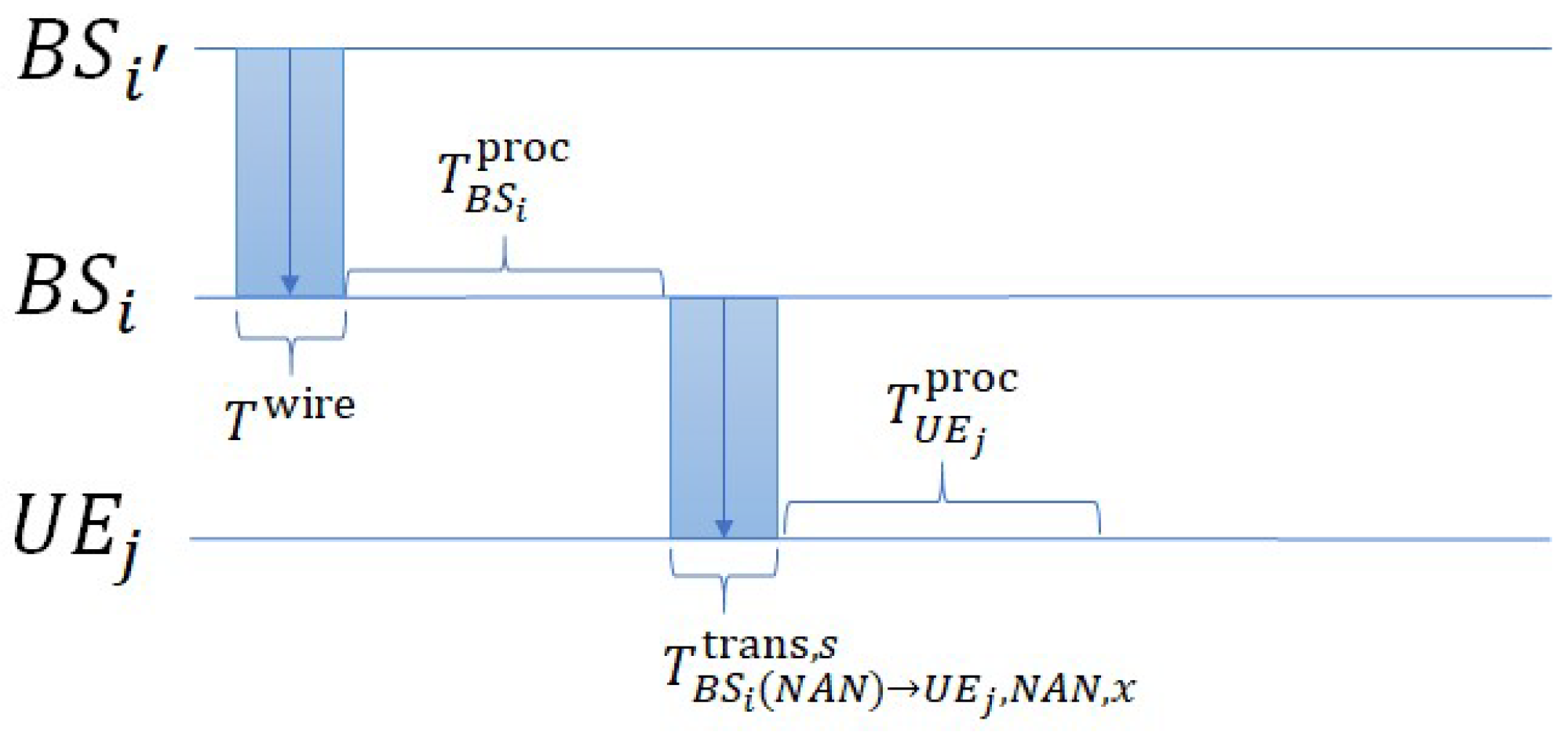

Downlink Mode C (non-local BS transmission without RIS): If

adopts Downlink Mode C, the packet flow follows

Figure 9. The delay is composed of four stages: (1) Backhaul propagation delay from the non-local BS

to the serving BS

:

. (2) Processing time at

:

. (3) Transmission time directly from

to

:

. (4) Processing time at

:

. This backhaul step exists because

cannot employ RIS; thus, the computed packet must first be forwarded to

.

Downlink Mode D (non-local BS transmission via RIS): If

adopts Downlink Mode D, the packet flow follows

Figure 10. The delay is composed of three stages: (1) Processing time at the non-local BS

:

. (2) Transmission time from

to

via

:

. (3) Processing time at

:

.

For packets processed by the local BS

(labeled

) or by the non-local BS

(labeled

), the downlink delay is:

For simplicity, the downlink payload size is set as , where denotes the downlink/uplink payload ratio. The corresponding transmission times and capacities are then expressed as follows:

Here,

and

respectively denote the SINR observed at

UEj and the corresponding data rate obtained as the calculation result when

directly transmits to

the

-th packet of service type

associated with

. Equations (13) and (14) are consistent with (1) and (2), respectively [

59,

60].

Here,

and

respectively denote the SINR observed at

and the corresponding data rate obtained as the calculation result when

transmits to

the

-th packet of service type

associated with

for subsequent forwarding to

. Equations (15) and (16) are consistent with (13) and (14), respectively [

59,

60].

Here,

and

respectively denote the SINR observed at

and the corresponding data rate obtained as the calculation result when

forwards to

the

-th packet of service type

associated with

. Equations (17) and (18) are consistent with (13) and (14), respectively [

59,

60].

Here,

and

respectively denote the SINR observed at

and the corresponding data rate obtained as the calculation result when

transmits to

the

-th packet of service type

associated with

for subsequent forwarding to

. Equations (19) and (20) are consistent with (13) and (14), respectively [

59,

60].

Here,

and

respectively denote the SINR observed at

and the corresponding data rate obtained as the calculation result when

forwards to

the

-th packet of service type

associated with

. Equations (21) and (22) are consistent with (13) and (14), respectively [

59,

60].

Note that the SINR terms in (18) and (22) include the signal-power gain contributed by RIS.

3.5.3. Total Delay

First, the total delay for a packet labeled

(or

), denoted as

(or

), is defined as the sum of four components: (1) The uplink delay:

. (2) The MEC computation time:

(or

). (3) The downlink delay:

(or

). (4) The inter-BS propagation delay:

(if applicable for a packet labeled

). Thus,

and

are expressed as

It should be noted that

already appears in the downlink delay expressions of (12), where it denotes the propagation delay associated with the returning transmission from the non-local BS

back to the serving BS

. Here, the additional

term accounts for the propagation delay of the forwarding transmission from the serving BS

to the non-local BS

when the packet is offloaded to a remote MEC server. Since

is defined as the propagation delay between two neighboring BSs over wired links, determined by distance and medium properties (e.g., fiber or copper), it is inherently direction-independent. Therefore, the same notation is consistently used in both cases. To model the MEC computation time, an equal-sharing abstraction is adopted. Let

denote the number of packets and sub-packets of service type

currently residing at

, and let

denote the corresponding quantity at the neighboring

. The total computation capacity allocated to service type

s is

, where

is the computation weight assigned to service type

. Similarly,

denotes the computation capacity of the neighboring MEC server

. Under the equal-sharing model, each (sub-)packet receives an equal share of the allocated computation capacity, yielding an effective computation rate of

at

and

at

. The corresponding MEC computation times are given by

This formulation captures the congestion-induced slowdown of MEC processing through a simple equal-sharing abstraction, without introducing explicit queueing delay.

Accordingly, the total delay of the original packet, denoted as

, is defined as the maximum of the near-part and far-part delays (when packet splitting occurs), since the packet is regarded as delivered only when both parts have been received:

If packet splitting does not occur, the total delay reduces to the near-part delay.

3.6. Problem Formulation

As introduced in

Section 1, we adopt the effective packet-delivery success percentage as the key performance metric, which intuitively represents the probability that packets are successfully delivered within the required latency bound. Formally, we denote this metric as

, defined as the fraction of packets that are transmitted to the BS, processed by the MEC, and returned to the originating UE within the latency requirement. Compliance with the latency bound is evaluated using the total delay

, which accounts for the entire process including uplink transmission, MEC computation, and downlink delivery.

We define an eight-element link configuration as (

), where

,

,

, and

. Here,

denotes the total number of packets of service type

s transmitted from

to

. The auxiliary elements in the link configuration are defined as follows. The variable

indicates whether a helper is employed, with

denoting that a helper

is used and

denoting that no helper is used. Similarly,

specifies whether a non-local BS is selected, with

denoting that a non-local

is adopted and

denoting that no non-local BS is used. Finally, RIS selection is represented by two binary indicators:

denotes whether

is employed (

) or not (

), and

denotes whether

is employed (

) or not (

). To ensure that at most one RIS is selected, we impose the constraint

. Let

denote the set of all such eight-element link configurations generated under the system parameters and assumptions. We further define

as the projection of

onto its first four elements, i.e., (

). The optimization problem is then expressed as

s.t.

C1 (Configuration membership):

C3 (Binary constraints):

where

denotes the maximum tolerable delay for packets of service type

. Constraint C1 ensures that each link configuration belongs to the feasible set

, while C2 ensures that a packet is counted as successful only if its total delay does not exceed the service-specific threshold. Constraint C3 enforces the binary nature of the auxiliary variables (

) and guarantees that at most one RIS can be selected by requiring

.

The optimization problem formulated above is applicable to general multi-cell scenarios, where handoff-like behaviors such as BS reassignment and path redirection naturally arise.

Since the formulated problem is an integer nonlinear programming problem, which is generally NP-hard, obtaining the exact optimal solution in large-scale scenarios is computationally intractable. Therefore, in

Section 4, we develop an efficient transmission-path selection algorithm with joint computation and communication resource allocation to tackle this problem. This algorithm is designed as a practical approximation of the optimization problem defined above. In particular, the binary indicators for helper selection (

), non-local BS selection (

), and RIS selection (

) are sequentially applied in the heuristic procedure to construct feasible transmission paths under latency constraints. In this way, the mathematical formulation is translated into implementable scheduling decisions. The proposed algorithm thereby provides a practical approximation of the optimization objective function, while respecting constraints C1–C3 and maintaining consistency with the mathematical formulation. This design ensures computational tractability in large-scale scenarios.

4. Proposed Transmission-Path Selection Algorithm

The proposed algorithm is organized as follows.

Section 4.1 introduces the remaining lifetime estimation, which evaluates the feasibility of candidate transmission paths.

Section 4.2 presents the downlink path selection strategy, distinguishing between near-MEC and far-MEC cases under different UE locations.

Section 4.3 describes the integrated transmission-path selection procedure, which combines all components into a unified framework for dynamic path determination.

4.1. Remaining Lifetime Estimation for Path Feasibility

After completing the preliminary simulations for MEC selection and proportional allocation, we compute the remaining lifetime

and

for packets labeled as

and

.

and

are defined as

and

respectively.

Here, the uplink delay, MEC computation time, and downlink delay are obtained from the preliminary simulations. For packets labeled

, the downlink delay applies only to Downlink Mode A (local BS direct transmission) in

Section 3.5.2, since

does not appear in the RIS-assisted region of

during the preliminary simulations. It should be noted that the delay values obtained from preliminary simulations may not fully match those observed during actual transmission.

4.2. Downlink Path Selection Strategy

For clarity, we define the internal service region of a BS as its coverage area excluding the overlap with its RIS-assisted region. When a computed packet enters the downlink queue (provided it has not overflowed), the BS determines the appropriate transmission strategy according to the packet label and the relative position of the UE. In scenarios where RIS assistance is applicable, facet selection is determined by the angular sector of the UE associated with the packet currently scheduled for downlink transmission. Under the single-beam assumption introduced in

Section 3.1, only this facet is activated, while other UEs in different facets are not assisted during that transmission instance. When multiple UEs are located within the same facet, only the UE selected under the downlink scheduling policy is assisted by RIS in that instance, while other UEs in the same facet are not served until they are scheduled in subsequent transmissions. In each downlink scheduling instance, the RIS forms only one directed beam toward the scheduled UE; beam switching within the same instance is not considered, to preserve tractability and avoid switching overhead.

The subsequent discussion is therefore divided into two cases: (a) packets labeled and (b) packets labeled . In case (a), where the packet is labeled , is regarded as a local user of . Three positional scenarios are then distinguished: Scenario (1) corresponds to the case where is located within the internal service region of ; Scenario (2) arises when is located in the RIS-assisted region of ; Scenario (3) occurs if is outside both the internal service region and the RIS-assisted region of . In case (b), where the packet is labeled , a portion of the packet has been allocated to even though is not directly connected to it. Similarly, three positional scenarios are distinguished: Scenario (1) corresponds to the case where is outside both the internal service region and the RIS-assisted region of ; Scenario (2) arises when is located in the RIS-assisted region of ; Scenario (3) occurs if is within the internal service region of

4.2.1. Packets Labeled

In the first scenario, the distance between

and

is relatively short, and direct communication is established between them. In the second scenario,

moves away from

and enters the RIS-assisted region of

. At this point, the received power from the serving BS tends to decrease, while that from the forward BS

may increase. In this situation,

is employed to help maintain the required signal strength above the handover threshold, which may help reduce additional delay. In the third scenario,

is located outside both regions. In this case, the computed packet is forwarded via wired backhaul to the forward BS

, which reconnects with the UE and continues the subsequent transmission following the rules defined above. These scenarios are summarized in

Table 2.

4.2.2. Packets Labeled

In the first scenario, the computed packet is returned via wired backhaul to the original BS

, which then handles the downlink transmission according to the rules defined in

Section 4.2.1. In the second scenario, the packet is transmitted from

to

with the assistance of

. In the third scenario,

is regarded as a local user of

, and the packet is directly transmitted by

. These scenarios are summarized in

Table 3.

4.3. Integrated Transmission-Path Selection Procedure

The proposed algorithm selects an efficient transmission path for each communication session through preliminary simulations. When generates packets (since multiple packets may be generated by at the same time, some may be discarded if they exceed ), it sends a signaling request to to indicate transmission demand. Every , executes the channel resource allocation algorithm for users with pending requests but without ongoing transmissions. Only users that successfully compete for transmission rights proceed to subsequent simulations, while unsuccessful users must wait for the next contention round. Since all packets generated by share identical service type and size, the preliminary simulation between and is performed using the first packet as a representative.

Once transmission rights are obtained,

performs a preliminary simulation of the uplink path, selecting between conventional communication and the helper-assisted D2D scheme described in

Section 3.2. The information on the chosen uplink path and packet size is then reported to

, which subsequently conducts the MEC selection and proportional allocation simulation described in

Section 3.3. If the packet is deemed processable, the algorithm further determines whether it will be handled solely by

or jointly by

and

. If the packet is deemed unprocessable, all packets in

’s buffer are discarded.

Next, the remaining lifetimes

and

are computed according to

Section 4.1. If no packet splitting is required (i.e., only packets labeled

), then two cases arise: (i) if

, the packet cannot be delivered within

, and all packets in

’s buffer are discarded; (ii) if

,

begins transmitting the packets in its buffer. If packet splitting occurs (i.e., packets labeled

and

), the remaining lifetimes

and

must be computed separately for both parts, and transmission proceeds only if both satisfy

and

. During transmission, if packets overflow

, they are discarded. Successfully received packets are forwarded either to

alone, or jointly to

and

, depending on the outcome of the preliminary simulation between

and

. Once all packets in

’s buffer have been transmitted, the transmission rights are released, and new packets must re-enter the contention process. The uplink transmission procedure is illustrated in

Figure 11.

After computation, a packet labeled

is returned from

to the transmission buffer of

, while a packet labeled

is returned from

to the transmission buffer of

. If the computed packet successfully enters the buffer, it undergoes the downlink transmission decision described in

Section 4.2; otherwise, it is discarded. At this stage, the BS selects the appropriate transmission method based on the packet label and the relative position of

. If the packet overflows

, it is discarded. Successful reception by

(for split packets, both the near and far parts must be received) indicates that the original packet has been completely delivered in both uplink and downlink, even if the delivery exceeds

. The corresponding downlink transmission procedure is illustrated in

Figure 12.

4.4. Complexity and Scalability Analysis

The proposed transmission-path selection algorithm is designed to remain tractable in large-scale MEC systems, consistent with the system model introduced in

Section 3. Each UE operates independently through localized simulations and binary decisions, while the serving BS performs MEC selection and proportional allocation only for UEs that successfully contend for transmission rights. Uplink path selection reduces to a binary choice between conventional and helper-assisted D2D, and downlink strategy relies on geometric classification into three positional scenarios per packet label. These operations are executed sequentially and locally, without requiring global optimization or joint scheduling across UEs.

The computational complexity per UE per cycle is , since each UE executes a constant number of simulations and binary decisions, independent of the total number of UEs or BSs. At the BS level, the aggregate computation scales as , where denotes the set of UEs associated with a given BS that have pending transmission requests but are not currently transmitting when that BS performs resource allocation. Only these UEs trigger BS-side contention resolution, MEC selection, and proportional allocation, so each contributes a constant processing cost in that cycle. Idle UEs and those already transmitting do not add overhead, ensuring that the per-cycle workload grows linearly with . Moreover, each BS interacts only with its own users and, if applicable, one candidate forward BS, so the per-BS complexity remains localized and independent of the global BS population.

This decentralized structure avoids coordination overhead and helps maintain scalability as both UE and BS populations increase. Consequently, the proposed algorithm strikes a practical balance between modeling fidelity and tractability, supporting real-time implementation in large-scale MEC networks.

5. Simulation Results and Discussion

To maintain clarity and computational tractability, our simulations focus on single-BS and dual-BS environments. The formulation introduced in

Section 3.6 and the algorithm described in

Section 4 remain structurally extensible to larger multi-cell scenarios.

5.1. Simulation Environment and Parameter Settings

We employ the network simulator 3 (NS-3) (version 3.42) to simulate both single-BS and dual-BS environments. Each BS is modeled as a micro cell with a coverage radius of 200 m. At the beginning of each simulation, 200 UEs are randomly deployed within the coverage area of each BS. The mobility of UEs follows the ConstantVelocityModel in NS-3: each UE is initially assigned a random velocity uniformly distributed between 20 and 100 km/h and a random direction between 0° and 360°. During the simulation, each UE moves according to its assigned velocity and direction. Once a UE moves beyond the coverage area of its serving BS, it continues at the same speed but reverses direction. In each BS environment, six RISs are deployed at angular positions of 0°, 60°, 120°, 180°, 240°, and 300°, each located 180 m from the BS. For calibration, each RIS provides a 20 dB gain for reflected signals when modeled with six equal-angle facets (default

). This 20 dB gain corresponds to the calibration reference defined in

Section 3.1; sensitivity to alternative gain values is examined in

Section 5.3 to validate robustness under the tractable facet-based RIS model. The single-beam assumption ensures that only one directed beam is formed toward the scheduled UE in each downlink scheduling instance. For simplicity, explicit phase-shift optimization is not incorporated; instead, the RIS contribution is modeled as a constant reflection gain within each facet, consistent with this abstraction. This approximation captures coverage geometry while deliberately avoiding the complexity of beamforming design, which lies beyond the scope of this study. A representative work on RIS phase optimization can be found in [

61]; extending our framework to incorporate optimized phase shifts is left for future work.

The system parameters are configured as follows.

MHz,

MHz,

,

,

ms, and

km/h. For all

, each BS is assigned identical parameter settings, including

MIPS,

dBm,

ms,

KB, and

KB. Similarly, for all

, each UE is configured with

dBm,

ms,

KB, and

KB. Since each helper is instantiated by a UE, helpers adopt the same configuration parameters as UEs. These processing times of 0.14 ms at the BS, UE, and helper follow a tractable NS-3-level abstraction and should be interpreted as simplified processing delays rather than detailed hardware-level implementations.

is randomly generated from a uniform distribution over the interval [0, 1] ms. In addition, service-type–related parameters are summarized in

Table 4. These parameter values constitute the default ideal values for subsequent analyses, unless explicitly varied in later sections. In the default simulation setting, the signaling overhead of the RTS/CTS handshake for helper-assisted D2D is assumed to be zero. This provides a consistent basis for comparing diverse transmission paths. The impact of non-zero overhead is examined in the sensitivity analysis presented later.

The channel model in this study involves both fading and path loss. Direct uplink channels (UE→BS) are modeled as Rayleigh fading with path loss exponent 3. In the helper-assisted D2D scheme, the UE→Helper link is modeled as Rician fading with path loss exponent 2.7 and a Rician K-factor of 3 dB, while the Helper→BS link is modeled as Rician fading with path loss exponent 2.5 and a fixed Rician K-factor of 6 dB. Downlink channels without RIS are modeled as Rayleigh fading with path loss exponent 3. RIS-assisted downlink channels (BS→RIS→UE) are modeled as Rician fading with a fixed Rician K-factor of 6 dB and path loss exponent 2.5. In addition, thermal noise is modeled with a density of −174 dBm/Hz at 290 K. For the uplink bandwidth of 40 MHz and BS noise figure of 5 dB, the resulting noise power is approximately −93 dBm. For the downlink bandwidth of 80 MHz and UE noise figure of 7 dB, the resulting noise power is approximately −88 dBm. These channel-related parameter values are substituted into the SINR-based transmission time and capacity formulas defined in

Section 3, providing the basis for all subsequent analyses.

To demonstrate the advantage of the proposed transmission-path selection algorithm, we establish a baseline algorithm that excludes both the helper-assisted D2D scheme and RIS-assisted transmission. Importantly, the baseline algorithm retains the same MEC cooperation framework as the proposed design, so inter-BS offload and the associated apply equally in both designs. This controlled benchmark isolates the incremental performance gains introduced by RIS and D2D, while ensuring that MEC cooperation effects are consistently accounted for in both designs. Resource allocation among multiple UEs contending for channel access is then carried out using two scheduling policies, the modified MR and the modified PF, yielding four strategies in total: proposed-MR, proposed-PF, baseline-MR, and baseline-PF. Both scheduling policies operate on the set . In the modified MR policy, the scheduling metric for each UE in is defined as its value, multiplied by the corresponding service-type weight (0.5 for URLLC, 0.3 for eMBB, and 0.2 for mMTC). The weighted values are sorted in descending order, and the top UEs are scheduled for transmission. In the modified PF policy, the scheduling metric for each UE in is defined as the ratio of its instantaneous transmission rate ( or ) to its historical average rate (). This ratio is then multiplied by a service-type weight (0.5 for URLLC, 0.3 for eMBB, and 0.2 for mMTC). The weighted metrics are sorted in descending order, and the top UEs are selected for simultaneous transmission. When the helper-assisted D2D uplink scheme is employed, the contention is represented by the originating UE for the entire path. Once the first hop successfully acquires channel resources, the second hop does not need to contend again.

We define as the packet generation rate of each UE (packets/s), and as the total packet generation rate in the environment, i.e., . The parameter is varied to evaluate performance. Using the FlowMonitor module in NS-3, we collect statistics for the four strategies under different values, focusing on two performance metrics: (i) the effective packet-delivery success percentage , and (ii) the average total delay , defined as , which represents the mean total delay of all successfully delivered packets of service type across all UEs in the environment, regardless of whether individual delays exceed their service-specific latency thresholds. Packets dropped due to buffer overflow, negative remaining lifetime, or MEC overload are excluded from this calculation. For the dual-BS environment, results are averaged across both BSs. For clarity, we denote _proposed-MR and _proposed-PF as the performance of the proposed-MR and proposed-PF strategies for service type , respectively, and _baseline-MR and _baseline-PF as the performance of the baseline-MR and baseline-PF strategies for service type . These four terms serve as generic placeholders for performance, which may represent either the effective packet-delivery success percentage or the average total delay, depending on the metric under discussion. By contrast, the notations total_proposed-MR, total_proposed-PF, total_baseline-MR, and total_baseline-PF are reserved exclusively for the effective packet-delivery success percentage aggregated across all service types. Finally, we conduct 10,000 independent simulation runs for each value ranging from 1000 to 6000 packets/s, with each run lasting 10 s.

5.2. Results Analysis

Section 5.2 provides a comprehensive performance analysis under the reference values defined in

Section 5.1, establishing a clear basis for comparison before sensitivity analysis in

Section 5.4.

5.2.1. Performance in the Single-BS Environment

Figure 13 compares the effective packet-delivery success percentages of different service types achieved by the proposed-MR and baseline-MR strategies in the single-BS environment. For the proposed-MR strategy, when

< 2000 packets/s, URLLC reaches approximately 93%, while both Total and eMBB remain above 85%, and mMTC achieves around 70%. Across

= 1000–6000, all four proposed-MR curves consistently outperform their baseline counterparts. The performance gap becomes more pronounced at higher traffic loads, particularly for mMTC, while Total and eMBB also maintain a relative advantage of approximately 3–4 percentage points. Even at

= 6000, the proposed-MR strategy shows a slower rate of degradation compared with the baseline-MR strategy. In contrast, for the baseline-MR strategy, the success percentages of Total, URLLC, eMBB, and mMTC remain relatively stable when

< 3000 packets/s (URLLC ~90%, Total/eMBB ~80%, mMTC ~67%), but once

exceeds 3000 packets/s, all four curves exhibit a sharp decline, with mMTC experiencing the steepest drop. This degradation is consistent with the increased likelihood of packet drops under higher

, where MEC load and uplink buffer occupancy tend to rise. These observations confirm that the proposed-MR strategy consistently outperforms the baseline-MR strategy across all service types, with the advantage increasingly significant under heavy traffic.

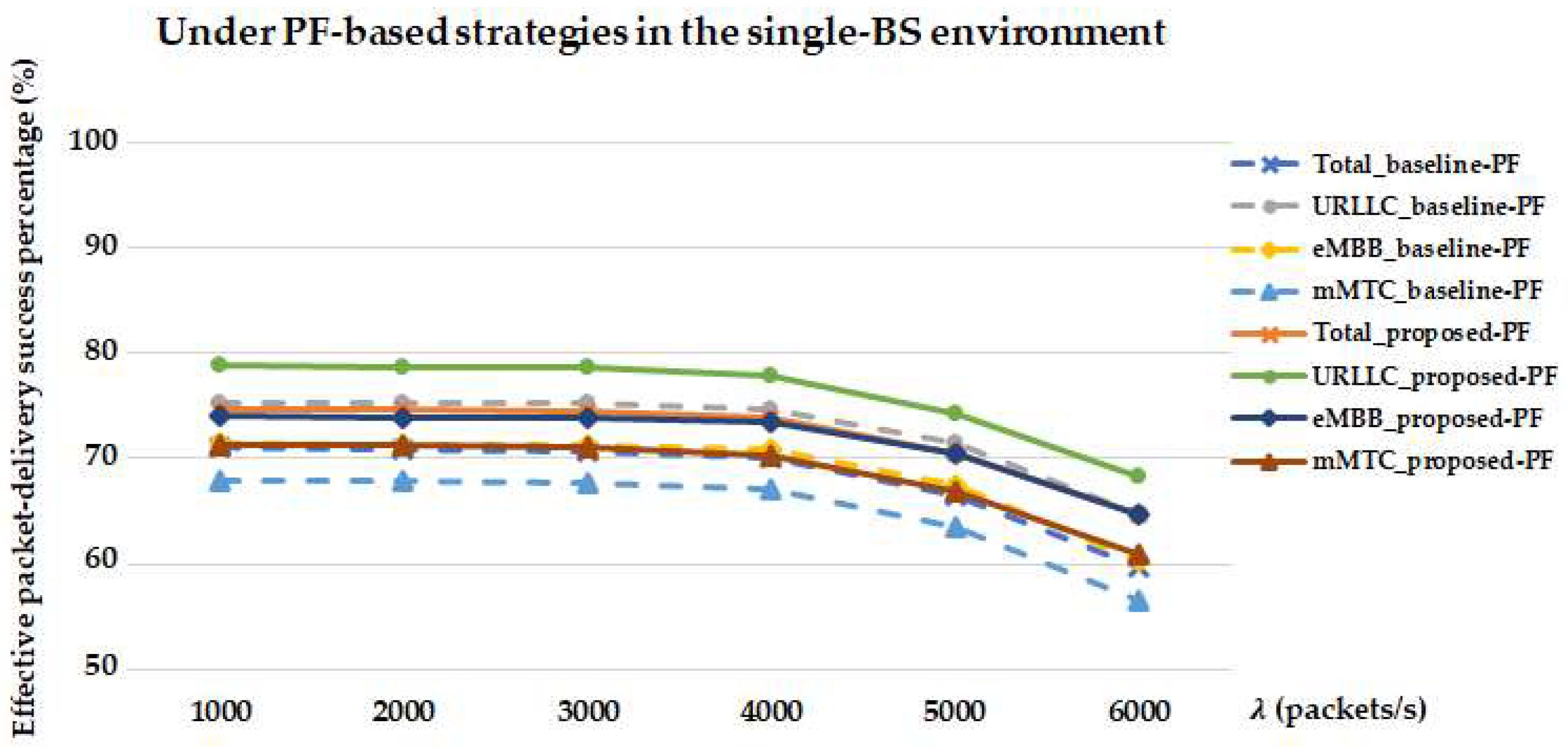

Figure 14 compares the effective packet-delivery success percentages of different service types achieved by the proposed-PF and baseline-PF strategies in the single-BS environment. For the proposed-PF strategy, although the success percentages are already below 80% at

= 1000 packets/s, which may be related to the modified PF scheduling occasionally selecting UEs with poor instantaneous channel conditions, increasing the likelihood of deadline violations, the proposed-PF strategy still achieves higher success percentages than the baseline. As

increases, all four proposed-PF curves consistently remain above their baseline counterparts, and the performance gap becomes more evident under heavy traffic loads. In particular, mMTC_proposed-PF shows the clearest advantage, while Total_proposed-PF and eMBB_proposed-PF also maintain a mid single-digit margin (about 5–7%). Even at

= 6000, the proposed-PF strategy continues to outperform the baseline-PF strategy, with a noticeably slower rate of degradation. In contrast, for the baseline-PF strategy, the success percentages of Total, URLLC, eMBB, and mMTC start below 80% at

= 1000 and decline further as

increases. Once

exceeds 4000 packets/s, all four baseline-PF curves drop sharply due to MEC overload and uplink buffer overflow, with mMTC experiencing the steepest degradation. These observations confirm that the proposed-PF strategy consistently provides better performance than the baseline-PF strategy across all service types, and that its relative advantage becomes increasingly significant under heavy traffic.

As shown in

Figure 13 and

Figure 14, MR-based strategies generally achieve higher success percentages than PF-based strategies for Total, URLLC, and eMBB, with the performance gap becoming more pronounced under heavy traffic. However, PF scheduling provides relative advantages for mMTC under heavy load due to its fairness-oriented allocation, while MR scheduling tends to favor latency-sensitive services by prioritizing UEs with higher instantaneous CQI. In both families, the proposed strategies benefit from helper-assisted D2D and RIS-assisted transmission paths, which increase route diversity and improve success percentages compared with their baselines. These observations are consistent with prior studies on QoS-aware scheduling [

62] and PF scheduling [

63], which highlight the throughput–fairness trade-off.

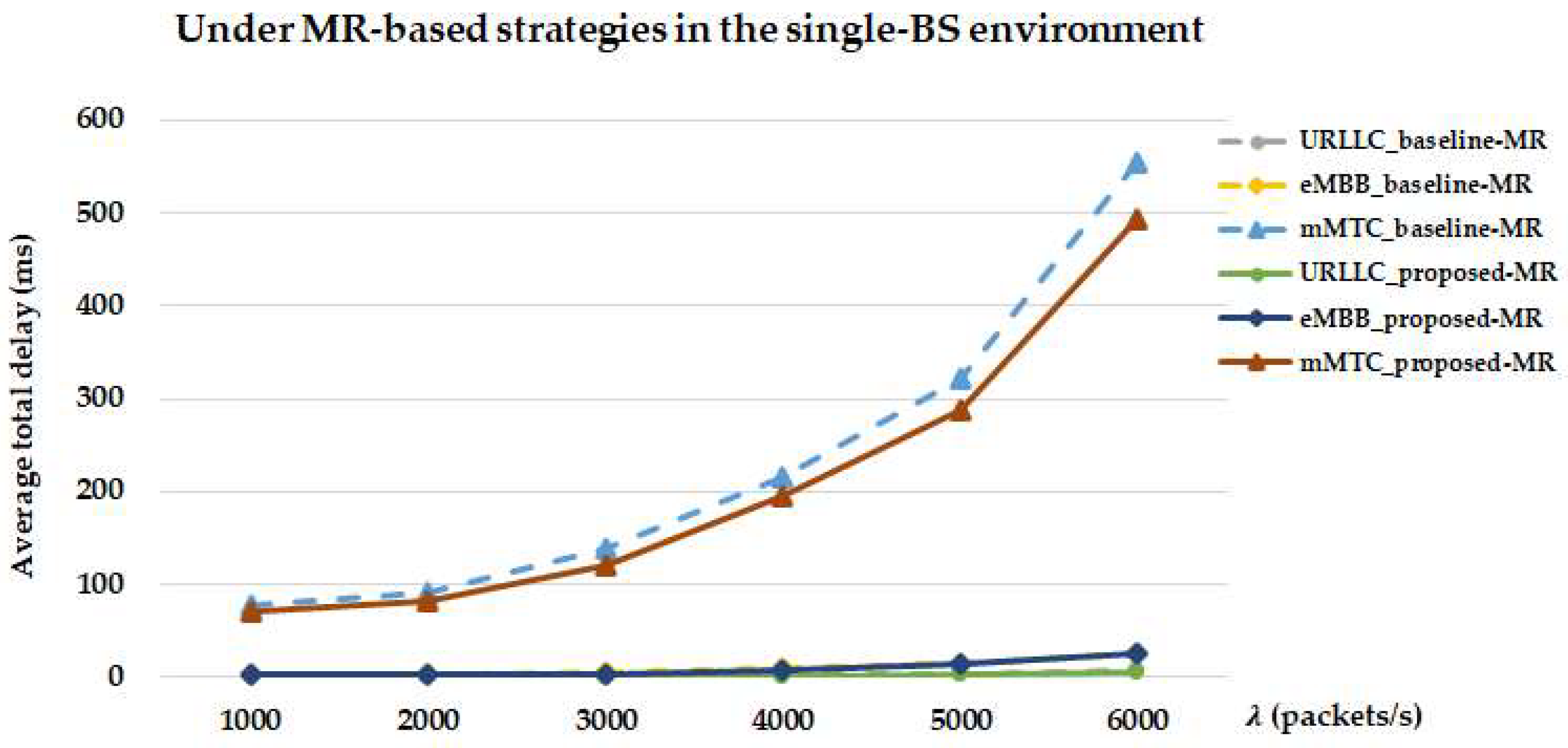

Figure 15 compares the average total delays of different service types achieved by the proposed-MR and baseline-MR strategies in the single-BS environment. For the proposed-MR strategy, when

,

, and

packets/s, the delays of URLLC_proposed-MR/eMBB_proposed-MR/mMTC_proposed-MR are 0.71, 1.97, 5.54/2.79, 8.08, 25.53/71.39, 195.58, 493.47 ms, respectively. In contrast, for the baseline-MR strategy, the corresponding delays of URLLC_baseline-MR/eMBB_baseline-MR/mMTC_baseline-MR are 0.95, 2.31, 8.71/3.33, 9.24, 26.15/78.45, 216.15, 554.32 ms. Across all traffic loads, the proposed-MR strategy consistently achieves lower delays than the baseline-MR strategy. This improvement is consistent with the additional helper-assisted D2D and RIS-assisted transmission paths, which can potentially provide alternative routes for UEs with poor channel conditions. Moreover, both strategies exhibit a sharp increase in delay at

compared with

and

. This trend is consistent with the increased queueing pressure at higher

, where later arriving packets tend to experience longer waiting times. In addition, UEs that pass the pre-simulation stage may carry more packets under higher

, which can lead to longer channel occupation times. A larger number of simultaneously transmitting UEs is consistent with lower SINR levels, which can prolong transmission time. Although URLLC exhibits the lowest delay across all service types, its latency still increases markedly under heavy traffic, demonstrating that even the highest-priority services cannot remain unaffected by network congestion. These observations confirm that the proposed-MR strategy consistently achieves lower delays than the baseline-MR strategy across all service types, with the advantage becoming increasingly significant under heavy traffic conditions.

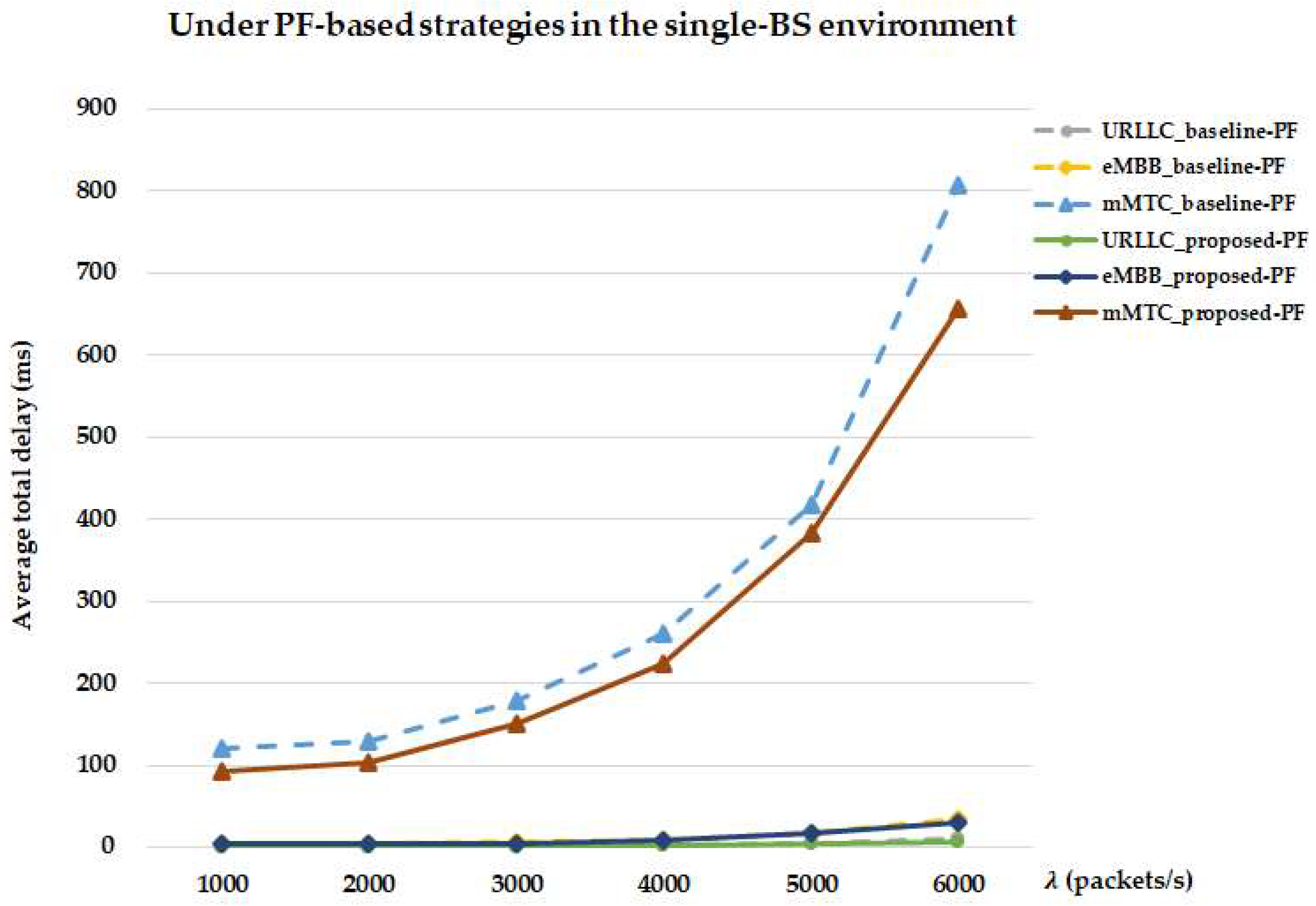

Figure 16 compares the average total delays of different service types achieved by the proposed-PF and baseline-PF strategies in the single-BS environment. For the proposed-PF strategy, when

,

, and

packets/s, the delays of URLLC_proposed-PF/eMBB_proposed-PF/mMTC_proposed-PF are 1.04, 2.56, 7.61/4.17, 9.08, 30.43/92.91, 224.55, 657.47 ms, respectively. In contrast, for the baseline-PF strategy, the corresponding delays of URLLC_baseline-PF/eMBB_baseline-PF/mMTC_baseline-PF are 1.31, 2.75, 10.73/5.05, 9.37, 34.15/119.77, 260.67, 806.32 ms. For any given

, the delays of the proposed-PF strategy are consistently lower than those of the baseline-PF strategy. The performance gain is consistent with the helper-assisted D2D and RIS-assisted mechanisms providing additional transmission opportunities for UEs with poor channel conditions. These observations confirm that the proposed-PF strategy consistently provides lower delays than the baseline-PF strategy across all service types, and that its relative advantage becomes increasingly significant under heavy traffic conditions.

As shown in

Figure 15 and

Figure 16, MR-based strategies consistently achieve lower average delays than PF-based strategies across all service types, with the performance gap becoming more pronounced under heavy traffic. MR scheduling tends to shorten transmission time by prioritizing UEs with better instantaneous channel quality, while PF scheduling aims to enforce fairness, which may lead to allocating resources to UEs with poorer channel conditions, thereby potentially increasing delay. Among all service types, mMTC exhibits the largest delay gap, highlighting that MR scheduling is particularly effective in mitigating latency. These delay results are consistent with prior studies on QoS-aware scheduling [

62] and PF scheduling [

63], which emphasize the throughput–fairness trade-off in latency performance under heavy traffic.

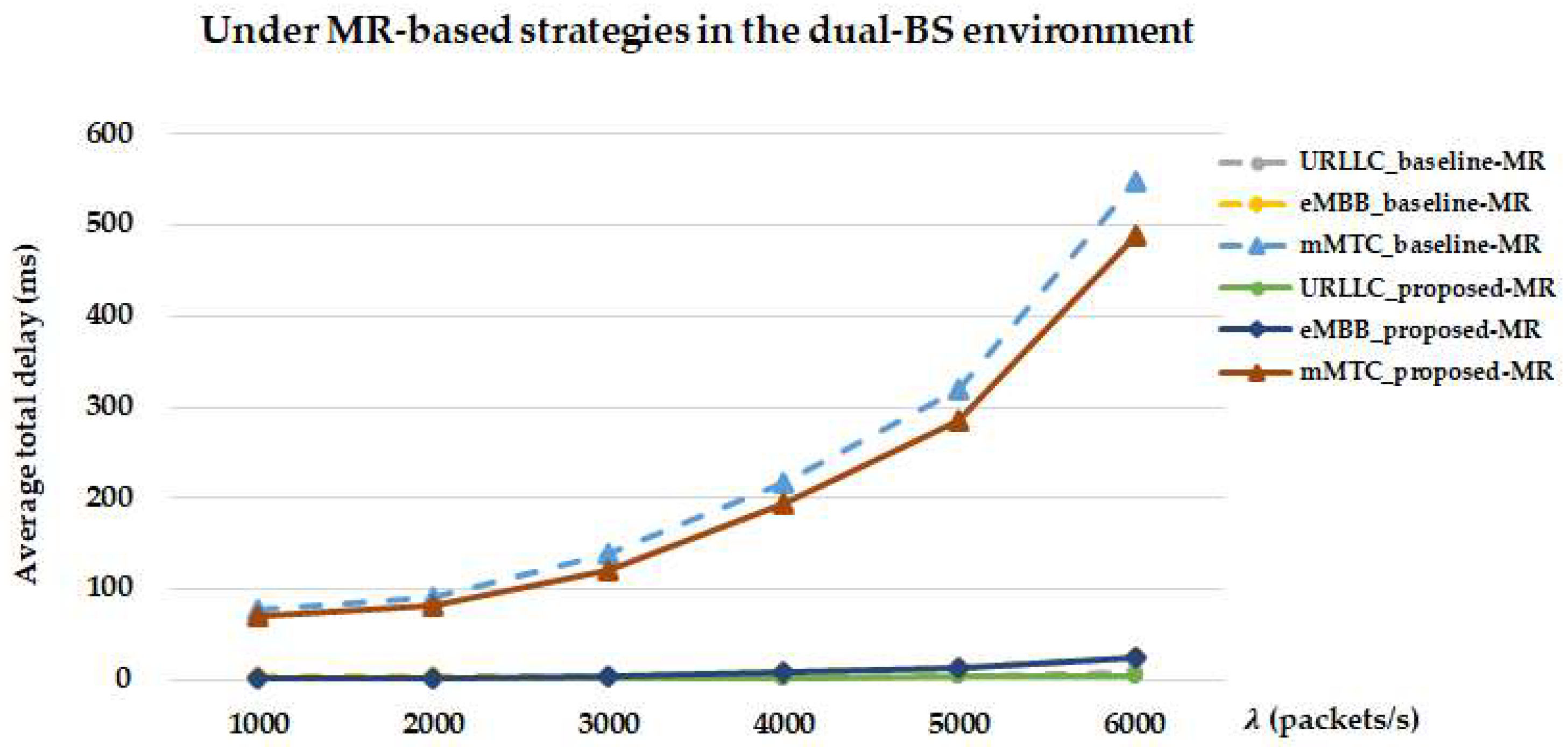

5.2.2. Performance in the Dual-BS Environment

Figure 17 compares the effective packet-delivery success percentages of different service types achieved by the proposed-MR and baseline-MR strategies in the dual-BS environment. Across the entire range of

from 1000 to 6000 packets/s, the proposed-MR strategy consistently outperforms its baseline counterpart for all service types (i.e., Total_proposed-MR > Total_baseline-MR, URLLC_proposed-MR > URLLC_baseline-MR, eMBB_proposed-MR > eMBB_baseline-MR, mMTC_proposed-MR > mMTC_baseline-MR). This improvement is consistent with the availability of helper-assisted D2D and RIS-assisted transmission paths, which may help provide additional diversity. The performance gap widens under heavy traffic, with mMTC showing the clearest relative advantage. For example, when

= 1000 and 6000 packets/s, the effective packet-delivery success percentages of Total_proposed-MR/URLLC_proposed-MR/eMBB_proposed-MR/mMTC_proposed-MR are 84%, 68%/94%, 76%/87%, 70%/70%, 58%, respectively, whereas those of Total_baseline-MR/URLLC_baseline-MR/eMBB_baseline-MR/mMTC_baseline-MR are 81%, 65%/91%, 73%/85%, 68%/68%, 54%.

Figure 18 compares the effective packet-delivery success percentages of different service types achieved by the proposed-PF and baseline-PF strategies in the dual-BS environment. A similar trend is observed: across

= 1000–6000 packets/s, the proposed-PF strategy consistently outperforms the baseline PF for all service types (i.e., Total_proposed-PF > Total_baseline-PF, URLLC_proposed-PF > URLLC_baseline-PF, eMBB_proposed-PF > eMBB_baseline-PF, mMTC_proposed-PF > mMTC_baseline-PF). For instance, when

= 1000 and 6000 packets/s, the effective packet-delivery success percentages of Total_proposed-PF/URLLC_proposed-PF/eMBB_proposed-PF/mMTC_proposed-PF are 75%, 67%/79%, 72%/74%, 67%/71%, 63%, respectively, whereas those of Total_baseline-PF/URLLC_baseline-PF/eMBB_baseline-PF/mMTC_baseline-PF are 72%, 62%/75%, 67%/71%, 62%/68%, 58%.

Figure 18 further shows that the effective packet-delivery success percentages of Total, URLLC, and eMBB are lower than their counterparts in

Figure 17, whereas the mMTC success percentage is higher. This pattern is consistent with PF-based scheduling distributing resources more evenly, which may lead to more balanced performance across service types, relatively higher mMTC success percentages but lower Total, URLLC, and eMBB success percentages. By comparing

Figure 17 and

Figure 18 with

Figure 13 and

Figure 14 (single-BS results), it is clear that both proposed and baseline strategies achieve higher success percentages and slower degradation in the dual-BS environment, which is consistent with the expected benefit of BS diversity. Across all scenarios, URLLC consistently maintains the highest success percentage, eMBB and Total remain in the middle range, while mMTC is the most sensitive to traffic load. These observations are consistent with prior studies on QoS-aware scheduling [

62] and PF scheduling [

63], which emphasize the throughput–fairness trade-off under diverse traffic conditions.

Figure 19 compares the average total delay performance of different service types achieved by the proposed-MR and baseline-MR strategies in the dual-BS environment. When

exceeds 3000 packets/s, the average total delay of all service types shows a clear upward trend, which becomes increasingly pronounced under heavier traffic. Specifically, when

= 1000, 3000, and 6000 packets/s, the average total delays of URLLC_proposed-MR/eMBB_proposed-MR/mMTC_proposed-MR are 0.70, 1.02, 5.21 ms/2.76, 4.30, 24.18 ms/71.24, 121.07, 488.03 ms, respectively, whereas those of URLLC_baseline-MR/eMBB_baseline-MR/mMTC_baseline-MR are 0.94, 1.32, 8.41 ms/3.27, 5.06, 25.17 ms/78.39, 138.18, 548.84 ms, respectively. Compared with the single-BS MR case (

Figure 15), all service types exhibit slightly reduced average total delays in the dual-BS MR case (

Figure 19). This modest reduction is consistent with the assumed parameter settings (

Section 5.1), under which the RIS provides sufficient reflection gain and the backhaul propagation delay

is modeled as having negligible impact on the overall latency. Under these assumptions, one BS could, in principle, segment portions of eMBB and mMTC packets and offload them to the other BS for parallel processing, which may help alleviate local MEC load in a model-consistent manner. These assumed conditions create a scenario in which the potential benefit of such parallelism can appear; otherwise, transmission overhead could offset the advantage, making single-BS processing preferable. Although the numerical reduction is modest, the trend is consistent across all three service types, with the relative gain more noticeable for mMTC and smaller for URLLC and eMBB.

Figure 20 compares the average total delay performance of different service types achieved by the proposed-PF and baseline-PF strategies in the dual-BS environment. When

> 4000 packets/s, the average total delays of all service types increase sharply compared with the case when

< 4000. Specifically, when

= 1000, 4000, and 6000 packets/s, the average total delays of URLLC_proposed-PF/eMBB_proposed-PF/mMTC_proposed-PF are 1.03, 2.47, 7.38 ms/4.21, 8.99, 29.16 ms/92.89, 224.52, 652.43 ms, respectively, whereas those of URLLC_baseline-PF/eMBB_baseline-PF/mMTC_baseline-PF are 1.31, 2.74, 10.49 ms/5.04, 9.33, 33.86 ms/119.76, 260.51, 801.34 ms, respectively. Compared with the single-BS PF-based case (

Figure 16), all service types exhibit slightly reduced average total delays in the dual-BS PF case (

Figure 20). As in the MR-based case (

Figure 19 vs.

Figure 15), this modest reduction is consistent with the assumed dual-BS environment, in which offloading between BSs could, in principle, redistribute computation load and alleviate local MEC pressure in a model-consistent manner. In addition, the steeper increase in delays under heavy traffic is consistent with the design of the modified PF policy, which balances instantaneous and historical rates and may limit the extent to which short-term channel peaks can be utilized under high load. While this balanced allocation helps prevent starvation, it may also reduce the likelihood of fully exploiting favorable instantaneous channel conditions, which may contribute to the sharper delay growth observed under heavy traffic.

Taken together,

Figure 19 and

Figure 20 demonstrate that, compared with the single-BS environment, the dual-BS environment yields modest but consistent reductions in average total delay across all service types under both modified MR and modified PF scheduling. However, their relative behavior under heavy traffic differs: with modified MR, delays increase more smoothly, which is consistent with resources being biased toward users with favorable channel conditions and allowing the system to better exploit instantaneous throughput opportunities. In contrast, modified PF enforces a more balanced allocation across users, which helps prevent starvation but may limit the ability to prioritize the best instantaneous channels. This behavior may contribute to a steeper increase in overall delays when the load becomes very high. These complementary observations highlight the throughput–fairness trade-off between MR and PF scheduling in the dual-BS setting, consistent with prior studies on QoS-aware scheduling [

62] and PF scheduling [

63].

5.2.3. Generality and Fairness in Comparative Analysis

The comparative evaluation across single-BS and dual-BS environments demonstrates the robustness of the proposed framework. By integrating helper-assisted D2D and RIS-assisted transmission, the framework consistently improves both effective packet-delivery success percentage and average delay compared with the baseline algorithm. These gains are evident under diverse scheduling policies, confirming that the improvements are not tied to a specific scheduler or topology.

To provide a more complete evaluation, we also report fairness results using Jain’s fairness index [

64], a widely adopted metric for quantifying the equity of resource allocation among UEs:

where

denotes the per-UE effective packet-delivery success percentages. The index satisfies

, with higher values indicating more equitable performance across UEs.

Table 5 summarizes Jain’s fairness indices for both single-BS and dual-BS environments. PF-based strategies consistently achieve higher fairness than MR-based strategies across all loads, reflecting their proportional allocation that mitigates UE starvation. Dual-BS diversity modestly improves fairness for all strategies. However, this fairness advantage is often accompanied by lower success percentages and higher delays most notably for latency-sensitive services under the modified PF scheduling, whereas the modified MR scheduling maintains superior latency and reliability for such services at the cost of reduced fairness under heavy load. Overall, these results highlight the trade-off between modified MR scheduling, which favors throughput-oriented prioritization, and modified PF scheduling, which balances resource allocation.

The core advantage of the proposed framework—integrating helper-assisted D2D and RIS-assisted transmission—over the baseline lies in its ability to potentially enhance performance under network resource bottlenecks by enabling diverse transmission-path selection. The results demonstrate that these mechanisms tend to provide consistent improvements across scenarios, systematically outperforming the baseline across all major performance metrics (success percentage, delay, and fairness). This advantage becomes especially critical under heavy traffic loads, where resource bottlenecks are most severe and fairness considerations become increasingly important. Overall, MR-based strategies tend to maintain higher reliability and lower latency under heavy load, reflecting their prioritization of users with favorable instantaneous channel conditions. In contrast, PF-based strategies generally achieve higher fairness across UEs, though this may come with lower success percentages and higher delays, particularly for latency-sensitive services. These observations highlight the inherent throughput–fairness trade-off between the two scheduling approaches.

5.3. Sensitivity Analysis of RIS Facet Number

This subsection performs a sensitivity analysis of the tractable facet-based RIS approximation by varying the facet number

, in order to evaluate its robustness. In the RIS literature, under ideal far-field conditions with perfect phase alignment, the effective gain scales approximately as

, where

denotes the number of controllable reflecting elements [

57]. In our tractable approximation, we do not explicitly model individual elements but instead discretize the reflector into

angular facets. Each facet corresponds to an angular sector of the reflector, representing the aggregate directional effect rather than a one-to-one mapping to individual elements. Thus, while

and

are not identical,

serves as a tractable proxy for effective gain. For calibration, we define

facets to correspond to an effective gain of 20 dB, thereby aligning the tractable approximation with the scaling law at a reference calibration point. This calibration point is somewhat optimistic compared to reported gains in current RIS prototypes, but it provides a convenient reference for sensitivity analysis. Other choices such as

or

would yield equivalent sensitivity trends once recalibrated, and thus the conclusions are not dependent on the specific calibration point. Other values of

are scaled using the following relation:

which preserves the monotonic scaling law while ensuring consistency with the chosen reference calibration point. The evaluation was performed in the single-BS environment under moderate mixed-service load (

= 3000 packets/s), using the modified PF scheduling policy. Results under the modified MR policy exhibited consistent relative trends and are omitted for brevity.

Table 6 reports aggregated outcomes computed over all delivered packets across URLLC, eMBB, and mMTC. The aggregated success percentage denotes the fraction of packets whose latency satisfies their respective thresholds. The aggregated average total delay is defined as the mean of the total delay experienced by each packet, regardless of whether individual delays exceed service-specific thresholds. Fairness is quantified by Jain’s index, computed per UE based on its individual success percentage, consistent with the definition in

Section 5.2.3. Here, the aggregated outcomes adopt the same definitions of success percentage and average total delay as in

Section 5.1, but differ in scope: they are computed across all service types (URLLC, eMBB, and mMTC) with packet-count weighting, whereas

Section 5.1 reports per-service results.

As shown, increasing

enhances the effective gain according to (35). With smaller

, the calibrated gain is reduced, which may lead to lower reliability in RIS-assisted transmissions. Larger

values correspond to higher gain, which can result in modest improvements in aggregated success percentage, aggregated average total delay, and fairness. For example, increasing

from 6 to 12 raises the aggregated success percentage from 74.5% to 77.2%, reduces the aggregated average total delay from 52.4 ms to 49.5 ms, and improves fairness from 0.88 to 0.90. Although absolute values vary with

, the overall performance trends remain consistent, and the proposed framework consistently outperforms the baseline across all tested values. These results suggest that the tractable sectorized approximation is reasonably robust to different choices of facet number, ensuring that the modeling approach in

Section 3.1 remains valid and reliable.

5.4. Sensitivity to System Parameters in the Dual-BS Environment

This subsection evaluates the robustness of the proposed framework under practical variations in backhaul propagation delay (

), RIS reflection gain, and helper-assisted D2D signaling overhead. The evaluation is conducted in the dual-BS setting with mixed service load (

= 3000 packets/s) using the modified PF scheduler. Aggregated metrics follow the definitions in

Table 6, except that

Table 7 reports service-level averages equally weighted across URLLC, eMBB, and mMTC (1/3 each), independent of the traffic generation probabilities in