1. Introduction

Generative AI (GenAI) agents have progressed from experimental demonstrations of concept to infrastructural actors mediating research, writing, coaching, and choice in education, finance, and the government [

1,

2]. As the agents are scaled up, adoption is a function not merely of technical ability but also of user familiarity with the system—whether the system is understandable, restricted by reasonable safeguards, useful to the task at hand, and unlikely to subject the user to harm [

2,

3]. Emerging evidence from user-centered research on explainable AI (XAI) suggests that experienced transparency—understanding the reasoning, sources, and limits of a model—can counteract negative perceptions and enhance trust and adoption, but these effects are typically small and sensitive to design. Meanwhile, policy and design efforts within responsible AI prioritize the importance of open guardrails—discernible limits, refusals, and policy revelations with controlled risk and explicit acceptable use [

2,

3]. Collectively, these strands suggest that reliable explanations and reliable safeguards must be dealt with simultaneously in order to achieve trust in real-world settings.

On the level of individual decision, modern acceptance studies exhibit a benefit–hazard calculus: perceived utility (possible performance improvements) and perceived risk (possible harms such as error costs or loss of privacy) both contribute to intention to use. Throughout domains—health, education, customer service, and organizational settings—ease of use and performance expectancy come before intention and use, yet their effects are inconsistent when credibility and risk are more prominent (e.g., in high-stakes or private settings) [

4,

5]. Findings from certain studies indicate that usefulness is more prominent than intention, while others conclude that usefulness declines after risk and trust are made explicit, or that organizational and social issues dominate sheer beliefs on performance when adoption is new [

6,

7,

8]. These differences most probably index heterogeneity in context, measurement, and interface signaling and motivate models that predict for utility as well as risk and trust in one structural explanation [

4,

6].

Trust constantly acts as the proximal cause of dependence, with results converging that illustrated automation-trust measures generalize effectively across AI environments [

1]. Conversely, user-focused tests warn that explanations are not enough; perceived explainability must reach salience and clarity levels in order to have an effect on trust or perceived usefulness, and affective aspects of the explanatory process may act as mediators of these outcomes. These findings validate keeping transparency as a user impression, not as a developer metric, and to quantify its effect along with risk and trust separately and not in aggregate [

1,

2]. A second, less frequently modeled mechanism is psychological reactance—the aversive response to perceived threats to freedom or agency. In automated or surveillant settings, reactance can be triggered by interface choices that signal control (e.g., preventive monitoring), by curation that narrows perceived choice (e.g., echo-chamber dynamics), or by social mimicry that feels inauthentic, producing downstream avoidance, lower attitudes, and disengagement [

9,

10]. Conversely, transparent expectations and supportive framings can de-threaten and restore agency. For GenAI assistants, this implies that the same design intended to reassure or “humanize” can backfire if it inadvertently heightens freedom threat. Incorporating reactance alongside trust is therefore critical for explaining why transparency and guardrail cues sometimes underperform in practice [

9,

10,

11].

Despite rapid development, the existing literature has four limitations that hinder the development of cumulative theory and design guidance. First, research combines the constructs of safety and transparency: “transparency” is operationalized as a general disclosure or explanation cue, and guardrails (visible boundaries, refusals, and policy cues) are excluded or absorbed into the same construct [

12]. These blurs separate psychological mechanisms—diagnosticity/traceability vs. assurance/risk containment—through which interface cues affect adoption. Second, while trust is firmly grounded as an antecedent of intention, reactance is seldom represented together with trust in a composite path; where present, it is more often a trait or post hoc rationalization than a design-sensitive mediator [

12,

13]. Third, results for usefulness are contingent on domains: usefulness occasionally overshadows intention, but in privacy-sensitive or high-consequence settings it attenuates when risk and credibility enter the picture. Previous research has the habit of assessing usefulness and risk separately, using heterogeneous operationalizations of risk (privacy vs. error cost vs. liability), or leaves out the joint estimation of usefulness, risk, trust, and reactance necessary to adjudicate between rival accounts [

14,

15]. Fourth, the majority of evidence is based on single-method, single-model inferences: experiments find small, design-sensitive explanation effects with zero external validity, and surveys apply linear SEM without experimenting with non-linearities, thresholds, or interactions that would detail under what conditions transparency and guardrails do alter behavior; invariance and heterogeneity checks are reported occasionally, and multilingual, ecologically based retrospective-use samples are still rare [

12,

16].

With these in mind, we identify four target user perceptions and two socio-cognitive mediators [

17,

18,

19]. Perceived transparency (PT) is the sense that the reasoning, steps, and sources of an assistant can be traced; perceived safety/guardrails (PSG) is how clearly limits, refusals, and policy guardrails are established and enacted; perceived usefulness (PU) is the anticipated task usefulness; and perceived risk (PR) is the expected downside of dependence [

19,

20]. We hypothesize that PT and PSG are design-perception levers offering two complementary channels: a risk–trust pathway (guardrails diminish perceived risk, which increases trust and intention) and a freedom–trust pathway (traceable reasoning and transparent rules diminish reactance, which increases trust and intention). This specification explicitly responds to the tendency to confuse transparency with measurement safety and the lack of modeling reactance and trust as concurrent mediators from interface signals to adoption [

17,

21].

To empirically test the dual-pathway model, a structural model of GenAI adoption was formulated and estimated to determine the relationships among transparency perceptions, guardrails, usefulness, risk, trust, reactance, and behavioral intentions using variance-based structural equations. To supplement the structural equation model with non-linear predictive insights, a Stage 2 artificial neural network model was applied to explore if these importance measures would still hold when flexible functional forms are permitted.

The rest of the paper is organized as follows.

Section 2 provides the literature review on GenAI adoption, separating design perception levers from evaluative lenses, with trust and reactance serving the role of mediators.

Section 3 introduces the conceptual framework, or the proposed model for the study.

Section 4 describes the study’s methodical framework, from sampling techniques to the procedure underlying the two levels of the study, namely the second level on predictive diagnostics, which is performed with ANN.

Section 5 interprets the study’s findings, from structural levels to predictive diagnostics, while

Section 6 presents the application usage of the study, including its application to policymaking, management, and educational circles.

Section 7 provides the study’s conclusions, with the synthesis of its contributions, followed by its limitations and future paths.

3. Research Methodology

3.1. Conceptual Model and Rationale

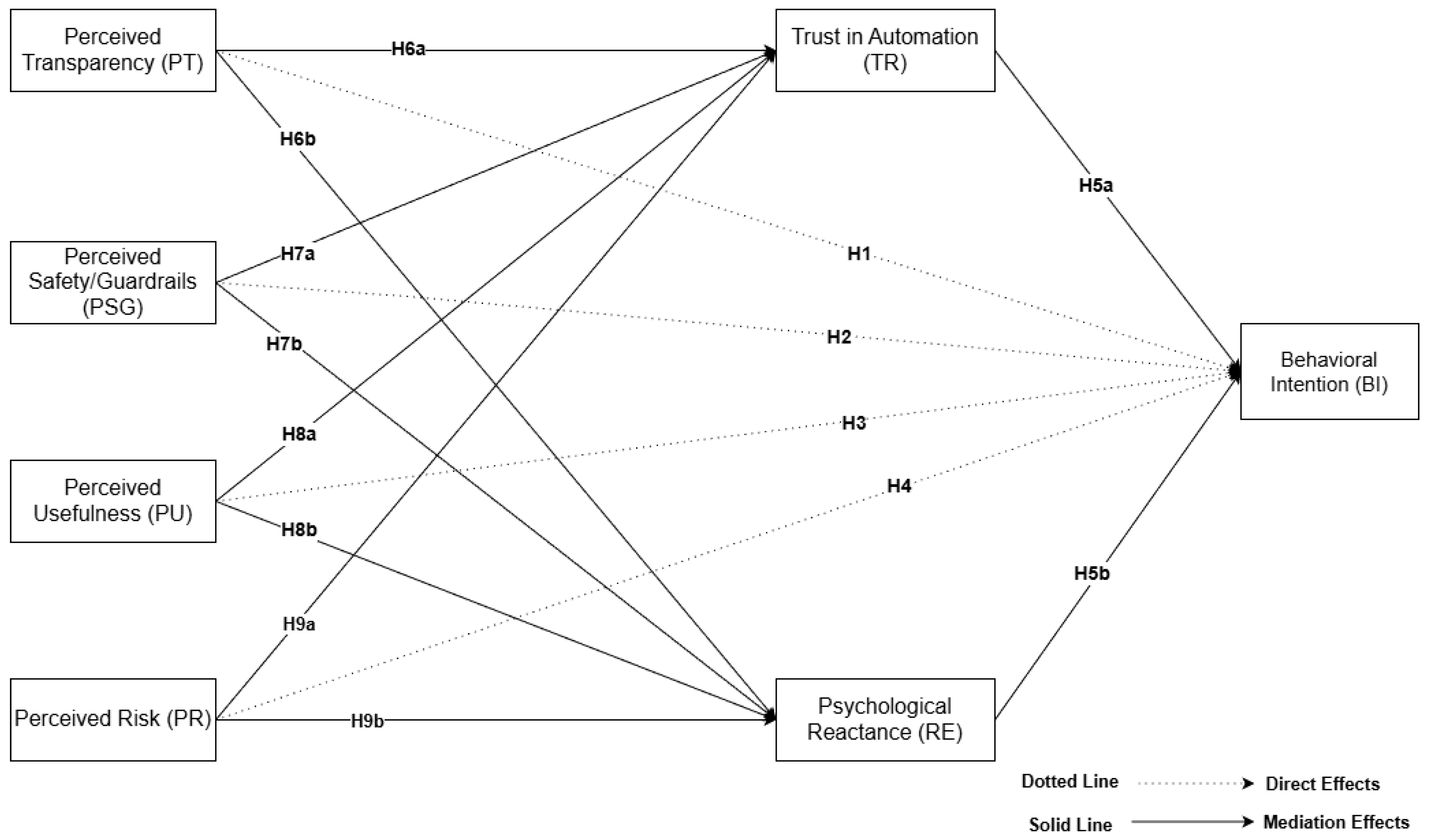

This research presents a design-oriented explanation of GenAI adoption by differentiating between two perceptions of interfaces—perceived transparency (PT) and perceived safety/guardrails (PSG)—and integrating them with perceived usefulness (PU) and perceived risk (PR) in an overarching, socio-cognitive framework to explain behavioral intention (BI). The model integrates ideas from TAM/UTAUT, trust in automation, XAI, risk communication, and reactance theory psychology to fill three gaps: pervasive blurring of transparency and safety, under-expression of RE as the complement of TR in adoption streams, and dis-integrated management of usefulness and risk that prevents intelligent design direction. By positioning PT and PSG as levers at interfaces and inferring PU and PR in conjunction, the architecture closes the gap between what systems signal and how they signal boundaries to the appraisals that regulate dependence in real-world contexts (

Figure 1).

Conceptually, PT is users’ expectation of an assistant’s reasoning traceability, steps, and sources; PSG is boundary, refusal, and policy protection transparency; PU is anticipated task value; PR is anticipated downside from reliance; TR is willingness to depend on the assistant in ambiguity; and RE is the aversive state after constraint or manipulation perception [

12,

16]. The model identifies two interactive routes: a risk–trust route via which guardrail cues influence hazard appraisals that impact trust and, derivatively, intention; and a freedom–trust route via which traceable explanation and explicit guidelines influence autonomy appraisals that impact reactance, which restricts trust and intention. PU and PR also have a straightforward connection with intention, in line with acceptance theory and with areas where performance beliefs or risk salience are most pivotal; they also affect trust as a consolidating belief regarding the advisability of leaning [

4,

5]. Fewer straightforward connections from PT and PSG are treated as robustness checks to maintain parsimony.

This specification has theoretic significance in the respect that it isolates comprehension-based effects (PT’s diagnosticity and sourceability) from assurance-based effects (PSG’s boundary-setting and error-containment), and explains why explanation cues sometimes mediate attitudes only when salient, credible, and user-interpretable, and safety cues redirect adoption particularly where task stakes or privacy salience is present. It also makes reactance a design-sensitive mediator instead of an unchangeable personality and describes the interface conditions under which “humanizing” or limiting features can suppress cooperation even if technical performance is sufficient [

19,

20,

21]. In practice, the model provides actionable knobs: invest in transparency features where threat of autonomy is high; reveal guardrails where hazard assessments predominate; and align performance messaging with guarantees to prevent signaling control or peril involuntarily. Empirically, it is projected using PLS-SEM based on a survey-only, multilingual, retrospective sample of ecologically developed attitudes, supported by a Stage 2 ANN to analyze plausible thresholds and interactions inapproachable via linear models. In so doing, it offers a balanced explanation of how interface hints influence judgments of usefulness and risk, how they move through trust and reactance, and when these flows create intention to use GenAI helpers.

3.2. Data Collection and Sampling

This research used a quantitative cross-sectional design and an online self-administered survey to explore the interrelationship between the respondents’ previous experience with GenAI advisors and perceived transparency, perceived risk, privacy concern, psychological reactance, trust, perceived usefulness, and intention to use [

62,

63,

64]. Sampling and data collection methods conformed to the theoretical model of the study—technology-adoption and trust-in-automation pathways estimated using SEM supplemented with a Stage 2 ANN for non-linear predictive diagnostics—and to the psychometric requirements for valid analysis of latent variables.

Sampling utilized a stratified purposive quota method conducted via a quality-checked online research panel supplemented with purposeful recruitment, seeking to recruit adults with recent exposure to AI-supported online services (e.g., university websites, bank or helpdesk chatbots) [

65,

66,

67]. Gender, age ranges (18–24, 25–34, 35–44, 45–54, 55+), and educational attainment (non-tertiary vs. tertiary) were used as quotas to procure maximum subgroup equilibrium for measurement invariance and multi-group SEM. Within strata, recruitment was conducted with invitations issued to fill quotas. This approach prioritizes conceptual relevance—asserting respondents’ capacity to report on GenAI experience meaningfully—while maintaining external validity through controlled representation of demographics. The co-deployment of an online panel of EU citizen members with prior experience with GenAI sets specific boundaries for generalization. Uninitiated persons and non-EU members are not included, and among those surveyed, knowledge level of GenAI varies greatly, with a large proportion with low knowledge, which could systematically differ from those with more knowledge about interface perceptions and evaluation.

Data were gathered via Google Forms. After screening for eligibility and electronic informed consent, participants initially read a short, unbiased definition of a GenAI assistant to ensure uniform understanding, then filled in all items retrospectively on their own use of such systems during the past 12 months. The tool merged scale-trialed Likert-type items (4–5 items per factor, five-point scales) for the target focal latent variables—perceived transparency, safety perception, perceived risk, privacy concern, psychological reactance, trust, perceived usefulness, and behavioral intention, along with demographic items and short digital-literacy indicators. The survey was administered in Greek and English; translation–back-translation by bilingual specialists and cognitive pretesting (≈10 participants) were employed to ensure semantic equivalence and readability. Responses were voluntary and anonymous, and no manipulation was used in experiments.

Inclusion criteria asked for adults (≥18 years), with very good Greek or English proficiency, residence in the EU, and self-report of having used AI-supported online services over the past year on an aided device (desktop, laptop, or mobile). These inclusion criteria allowed the participants to offer informed consent, understand the questionnaire, and report experience-based judgments regarding GenAI interaction. Exclusion criteria—pre-registered for internal validity—excluded cases with no applicable prior exposure, greater than one attention/consistency check failure, implausibly brief completion times (less than one-third of median page time), stereotypical “long-string” responding, irrational open-ended attention probe responses, or duplicates suspected by panel/device/IP controls. Automated red flags were complemented by hand coding of open-ended content.

Pretesting in a small convenience sample (≈30–40) was conducted in order to assess timing, wording, and salience of the framing definition; small textual and layout modifications ensued. In the main wave, procedural controls against common-method bias involved psychological distance between predictors and outcomes (with a brief neutral filler section intervening), randomized item presentation, mixed stems/anchors, and verification of anonymity. Measurement quality was established using internal consistency (Cronbach’s α and composite reliability), convergent validity (average variance extracted ≥0.50), and discriminant validity (Fornell–Larcker criterion and HTMT < 0.85) and full-collinearity VIFs (<3.3). For the ANN stage, standardized latent scores of the exogenous constructs were used to train a multilayer perceptron with early stopping, predictive performance (MAE/RMSE) was benchmarked against linear baselines, and interpretability was supported with importance values and individual conditional expectation plots.

An aggregate of approximately 420 completes was planned to include anticipated 10–15% quality-based exclusions to yield an analytical sample of approximately 360–380 observations. This sample size was a priori warranted: inverse square-root and gamma-exponential strategies provided ≥0.80 power to detect small-to-medium structural effects (β ≈ 0.15–0.20) in the most challenging parts of the model, the conservative “10-times rule” was met [

68,

69,

70], CB-SEM sensitivity analyses (robust ML) at N ≈ 350–400 yield detection of standardized loadings ≥0.55 and paths ≥0.15 with 0.80 power, and the SEM–ANN stage was aided by N ≥ 350 for stable 70/30 train–validation–test splits with 10-fold cross-validation and respectable non-linear importance diagnostics.

The study was cleared by the authors’ institutional ethics committee (insert committee name and ID). Voluntary participation was requested, and electronic informed consent was collected before data collection; respondents were free to withdraw at any time without consequence. No identifying information was retained other than panel identifiers necessary for compensation reconciliation. Processing was in line with GDPR principles of lawfulness, purpose limitation, and data minimization, and encrypted institutional drives with limited access were used to store files. Vulnerable adults and minors were not recruited, and the eligibility screen kept them from registering. The research was preregistered (hypotheses, design, exclusion criteria, and analysis plan), and—upon publication—de-identified data, code, prompts, and a data dictionary will be stored in an open repository.

3.3. Measurement Scales

All latent constructs were operationalized reflectively using multi-item Likert scales (see

Appendix A,

Table A1). Perceived transparency (PT) measured users’ perception of traceability and diagnosticity of assistant responses with four items (PT1–PT4: “I could see how the assistant arrived at its answers”; “The assistant’s explanations were clear and detailed”; “I could verify sources or evidence behind its answers”; “It was easy to follow the steps the assistant took”), drawn from validated XAI/transparency tools [

12,

14]. Perceived safety/guardrails (PSG) measured salience of boundaries, refusals, and policy guardrails on four items (PSG1–PSG4, e.g., “The assistant clearly delineated what it would and wouldn’t do”; “I had the sense that protection was built-in to stop dangerous advice”), adapted from risk-communication and responsible-AI disclosure scales [

71,

72]. Perceived usefulness (PU) measured anticipated benefits of performing tasks using four items (PU1–PU4, e.g., “Using such an assistant makes me more productive”), adopted from TAM/UTAUT performance-expectancy items [

73,

74]. Psychological reactance (RE) evaluated perceived threat of freedom while being guided by humans and AI with four items (RE1–RE4, e.g., “I become irritated when an assistant attempts to guide me towards a specific action”), adopted from established psychological reactance scales for technology use [

15,

16]. The items were measured at the level of their relevance for “such assistants” (e.g., feeling irritation at steering and constraining) rather than at a pure statement level. It should be noted, however, that these items still reflect responsiveness to freedom threats which can combine with design-induced responses and relate to state-like readiness to disregard guidance when engaging with human and artificial intelligence systems—that topic will be addressed below when considering the null findings. Trust in automation (TR) was used to assess willingness to trust in conditions of uncertainty with four items (TR1–TR4, e.g., “I believe such assistants are trustworthy”), based on human–automation/AI trust scales [

13]. Behavioral intention (BI) was used to assess short-term adoption likelihood with four items (BI1–BI4, e.g., “I would use such assistants in the next 3 months”), derived from TAM/UTAUT intention measures. Item stems and phrasing were equated to a survey-only, retrospective frame (“such assistants”), with neutral, non-leaded phrasing and no double-barreled phrasing [

75].

3.4. Sample Profile

A total of 365 adults participated in the survey, with 51.2% of them women (

Table 1). The age breakdown was 18 to 24 (31.5%), 25 to 34 (25.8%), 35 to 44 (23.6%), 45 to 54 (11.5%), and 55 or older (7.7%). The educational levels reported for the group consisted of secondary or below (21.9%), post-secondary/vocational qualifications (34.8%), baccalaureates (31.2%), and master’s degrees or higher (12.1%). Regarding the main uses of GenAI, the responses received covered search/everyday tasks (29.9%), coding/data/tech work (27.4%), educational/learning/teaching (11.0%), or office/customer support tasks (6.3%); the other 25.5% reported other or all-of-the-above uses. Responses about how familiar the interviewees actually are with the available AI resources also indicated low/very low familiarity levels in 43.3%, moderate familiarity levels in 21.4%, or high/very high levels of familiarity in 36.4% of the cases examined. Turning to the question about its treatment of users’ data, 44.1% reported sometimes providing their own data, which is regarded, nonetheless, as non-sensitive or perhaps sensitive, 20.8% often included personal data, 21.9% rarely or never did so, and 9.6% preferred not to say. Usage frequency was daily or almost daily for 18.4%, several times per week for 15.6%, weekly for 21.1%, monthly for 25.2%, and less than monthly for 19.7%.

4. Data Analysis and Results

We applied structural equation modeling in SmartPLS 4 (v4.1.1.4). According to Nitzl et al. [

76], variance-based SEM is suitable for business and social science applications. PLS-SEM was chosen because it maximizes explained variance of endogenous constructs and has a focus on predictive relevance [

77]. Multi-Group Analysis explored unobserved heterogeneity by comparing structural paths across subpopulations, thus detecting contextual differences that would not have been possible with standard regression [

78]. Estimation followed the guidelines of Wong [

79] in the computation of path coefficients, standard errors, and reliability indices. For reflective measures, indicator loadings ≥0.70 were considered acceptable as threshold levels to establish convergent validity. This workflow has enabled us to rigorously test the structural relationships and perform robust measurement evaluation within and across respondent groups.

4.1. Common Method Bias (CMB)

The potential of common method bias was measured by following the procedures of Podsakoff et al. [

80]. It checks whether a single latent factor dominates the covariance by the Harman single-factor test. A factor analysis without rotation resulted in the first factor explaining 25.452% of the variance, well below the conventional threshold of 50%. Therefore, CMB is unlikely to pose a threat to the findings. By documenting low CMB, this study has enhanced the construct validity and the credibility of the relationships between constructs, reducing the problem of systematic measurement bias [

80,

81].

4.2. Measurement Model

The PLS-SEM workflow followed next with the assessment of the reflective measurement model. In concert with Hair et al. [

77], we evaluated composite reliability (CR), indicator reliability, convergent validity, and discriminant validity to establish psychometric adequacy before the interpretation of the structural paths. Indicator reliability was defined as the proportion of item variance explained by its latent construct and examined via outer loadings following Vinzi et al. [

82]. Following Wong [

79] and Chin [

82,

83], loadings ≥0.70 were treated as acceptable indicators of item quality. Acknowledging that social science measures often fall below this benchmark [

83], item retention was not automatic. All deletion decisions were based on incremental gains in model quality: the rule of thumb was to retain indicators that increased CR and AVE and remove them only when their exclusion produced a clear, substantive enhancement in these indices as a means of avoiding discarding potentially informative measures prematurely.

The items with loadings between 0.40 and 0.70 were removed only if their removal substantially improved the CR or AVE of the respective construct. Based on these criteria and guided by the decision rules of Gefen et al. [

84], two indicators, RE4 and TR4, which demonstrated loadings less than 0.50, were dropped in the process of purifying the measurement model. As shown in

Table 2, this parsimonious refinement enhanced the quality of the measurement model without substantially reducing construct representation, thus being sufficient for further structural estimation and hypothesis testing (

Table 2).

Reliability was examined by using Cronbach’s alpha, rho_A, and composite reliability (CR). In line with Wasko et al. [

85], the 0.70 threshold was reached for BI, PR, PSG, PT, PU, RE, and TR, while for the other constructs, rho_A also showed a moderate to high reliability as found in previous studies as well [

86,

87]. Given that rho_A conceptually falls between alpha and CR, its values were above 0.70 for most constructs, thus supporting the findings of rho_A regarding reliability by Sarstedt et al. [

88] as well as the criteria related to consistency by Henseler et al. [

87].

There was also support for convergent validity, since the AVE surpassed 0.50 for most constructs. Following Fornell et al. [

89], AVE scores slightly less than 0.50 were still considered acceptable when combined with CR > 0.60, a requirement that was met in those cases. Discriminant validity was established based on the Fornell–Larcker criterion, as the square root of the AVE for each construct was greater than its interconstruct correlations, but was also further established using HTMT ratios below the conservative threshold of 0.85 suggested by Henseler et al. [

87]. Overall, these diagnostics suggest good construct validity and a strong degree of internal consistency across the measurement model. Specific indices (alpha, rho_A, CR, AVE, interconstruct correlations, and HTMT) are presented in

Table 3 and

Table 4.

4.3. Structural Model

Reliability was assessed by Cronbach’s alpha, rho_A, and composite reliability (CR). In line with Wasko et al. [

85], the 0.70 threshold was surpassed for BI, PR, PSG, PT, PU, RE, and TR; even the remaining constructs revealed reliability ranging from moderate to high, as suggested in previous studies [

78,

90]. This is viewed as a coefficient that is conceptually positioned between alpha and CR; thus, in most cases, rho_A exceeded the threshold of 0.70, in support of the reliability estimates shown by Sarstedt et al. [

90], hence meeting the consistency threshold recommended by Kock et al. [

68].

The coefficient of determination, predictive relevance, and path significance were used to check the structural model [

78]. It accounted for 47% of the variance in behavioral intention, with an R

2 of 0.470, 25.7% in psychological reactance with an R

2 of 0.257, and 19.5% in trust with an R

2 of 0.195, thus having a moderate explanatory power. Predictive relevance was established when the cross-validated redundancy or Q

2 showed values of 0.231, 0.174, and 0.393 for the endogenous constructs, which is consistent with moderate-to-strong out-of-sample prediction.

Hypotheses were tested using nonparametric bootstrapping following Hair et al. [

91], yielding path estimates and standard errors. Indirect effects were assessed with a bias-corrected, one-tailed bootstrap procedure with 10,000 resamples, as described by Preacher et al. [

92] and Streukens et al. [

93]. Overall, these diagnostics substantiate the model’s structural adequacy and predictive capability. Full estimates are presented in

Table 5.

Path coefficients (β), bootstrap standard errors (SE), t values, and exact p-values were used to test direct effects on BI. As expected, PT exhibited the highest positive relation with BI: β = 0.386, SE = 0.050, t = 7.75, p < 0.001 (H1 supported). In turn, TR was positively related to BI: β = 0.264, SE = 0.047, t = 5.68, p < 0.001 (H5a supported). PSG showed a smaller association with BI that was still statistically significant: β = 0.133, SE = 0.053, t = 2.52, p = 0.006 (H2 supported). In addition, PU demonstrated a modest positive relation with BI: β = 0.093, SE = 0.050, t = 1.85, p = 0.032 (H3 supported). In contrast, PR did not have a significant association with BI: β = −0.017, SE = 0.048, t = 0.34, p = 0.366 (H4 not supported), and RE was not a significant predictor: β = 0.064, SE = 0.047, t = 1.37, p = 0.085 (H5b not supported). In general, these findings indicate that BI is most strongly associated with perceptions of transparency and trust, with additional, smaller contributions from perceived safety/guardrails and usefulness. Neither risk nor reactance explained unique variance in BI in the presence of the other predictors.

4.4. Mediation Analysis Results

We adopted bias-corrected bootstrapping with 10,000 resamples to test indirect effects, reporting standardized coefficients (β), bootstrap standard errors (SE), t values, and

p values. Total effects were also investigated to contextualize mediation in terms of direct paths (

Table 6).

PT had a significant total effect on BI: β = 0.473, SE = 0.048, t = 9.93, p < 0.001, which was larger than its direct effect: β = 0.386, SE = 0.050, t = 7.75, p < 0.001. The indirect effect of PT → trust (TR) → BI was significant: β = 0.071, SE = 0.020, t = 3.56, p < 0.001, thus supporting H6a with partial mediation, while the PT → psychological reactance (RE) → BI path was not significant: β = 0.016, SE = 0.013, t = 1.21, p = 0.113, hence not supporting H6b. For PSG, there was a significant total effect on BI: β = 0.210, SE = 0.050, t = 4.17, p < 0.001, and a smaller but significant direct effect: β = 0.133, SE = 0.053, t = 2.52, p = 0.006. The indirect effect of PSG → TR → BI was significant: β = 0.058, SE = 0.019, t = 2.97, p = 0.002, hence supporting H7a, while the PSG → RE → BI path was insignificant: β = 0.020, SE = 0.016, t = 1.29, p = 0.098, hence not supporting H7b. These results support partial mediation through TR. PU had a significant total effect on BI: β = 0.104, SE = 0.053, t = 1.96, p = 0.025, with a modest direct effect: β = 0.093, SE = 0.050, t = 1.85, p = 0.032. The PU → TR → BI indirect effect was not statistically significant at α = 0.05, β = 0.015, SE = 0.015, t = 1.02, p = 0.055 (H8a supported under conventional criteria), and the PU → RE → BI path also did not reach significance: β = −0.004, SE = 0.005, t = 0.75, p = 0.227 (H8b not supported). Overall, results are most consistent with no mediation for PU. PR had a non-significant direct effect on BI: β = −0.017, SE = 0.048, t = 0.34, p = 0.366, and a non-significant total effect: β = −0.027, SE = 0.051, t = 0.53, p = 0.299. The indirect path PR → TR → BI was significant: β = −0.014, SE = 0.018, t = 0.78, p = 0.018 (H9a supported), but the path PR → RE → BI was not: β = 0.004, SE = 0.006, t = 0.57, p = 0.286 (H9b not supported). Because the direct effect is non-significant and the indirect effect via TR was significant, findings point to indirect-only (full) mediation via TR for PR.

Collectively, mediation occurred consistently via trust (for PT and PSG: partial; for PR: indirect-only), with no support for reactance-based indirect effects. It is concluded that these patterns are in line with a risk–trust channel, whereby interface signals improving transparency and guardrails mainly have their impact on intention through trust rather than through reactance.

4.5. Neural Network Augmentation (Stage 2 ANN)

Conventional linear techniques—such as multiple regression and covariance- or variance-based SEM—are well suited for theory testing, but often underrepresent the complexity of adoption decisions that can involve non-linear, non-compensatory, and interactive relationships among perceptions of transparency, safety, risk, and trust. Complementing our linear structural tests, therefore, we added a Stage 2 artificial neural network—a technique noted for flexible function forms without strict distributional assumptions and strong predictive accuracy in technology-adoption contexts [

94,

95,

96]. Because ANNs are not designed for hypothesis testing and offer limited causal interpretability—the so-called “black-box” caveat [

97,

98]—we used them strictly as a second-stage, predictive complement once SEM had already identified significant structural paths, following the recommended hybrid, two-stage logic in prior work [

97].

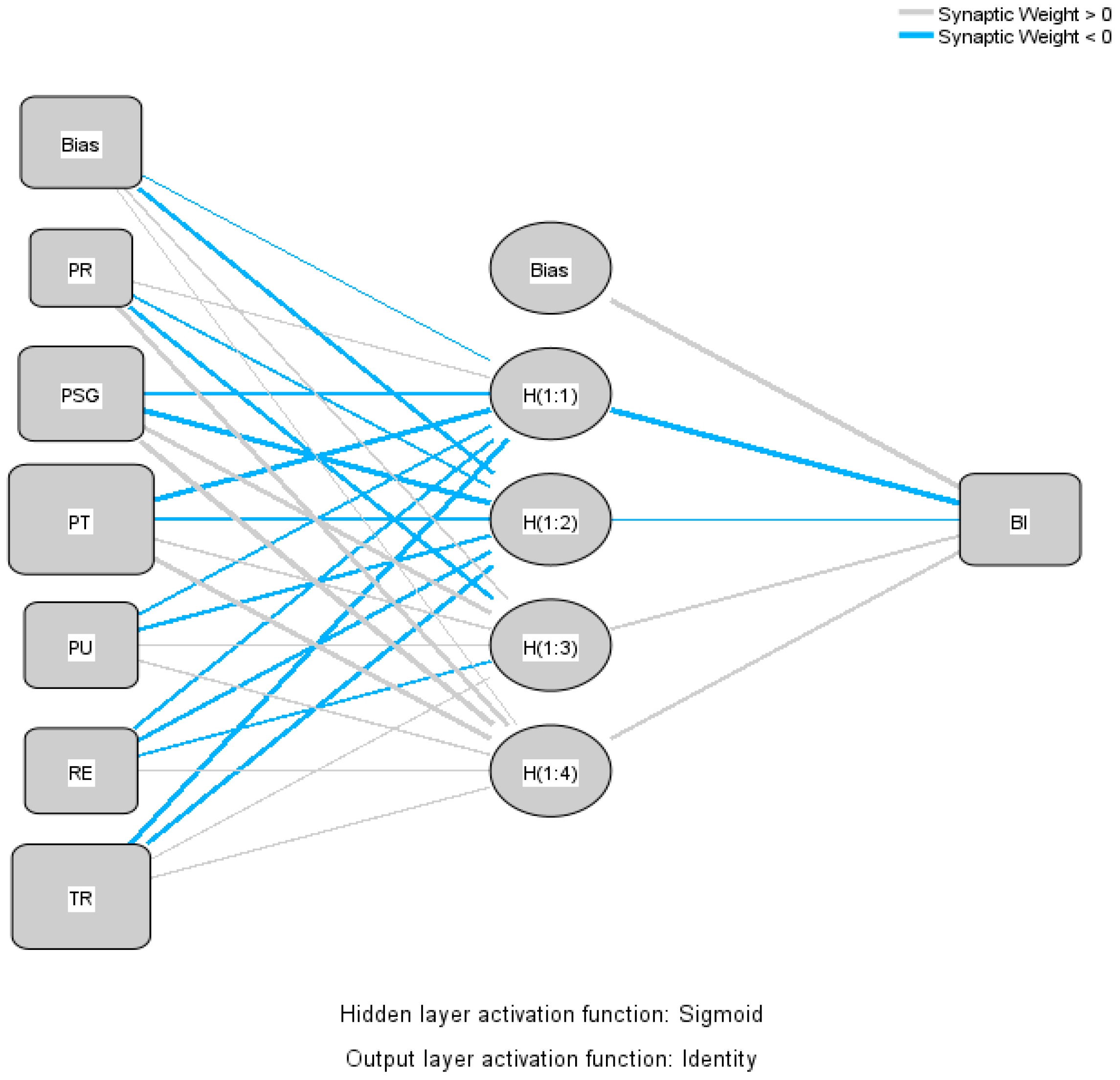

We implemented a feed-forward multilayer perceptron (MLP) in IBM SPSS Statistics v.29, and a feed-forward multilayer perceptron (MLP), taking the continuous latent score for behavioral intention as the target [

94,

95,

96]. Predictors were the latent composites perceived transparency, perceived safety/guardrails, perceived usefulness, perceived risk, trust, and reactance, which were entered as standardized covariates. Cases were randomly partitioned into 70% training/30% testing, with early stopping on the testing loss guarding against overfitting. Consonant with common guidance that one hidden layer is sufficient to approximate continuous functions in adoption models [

99,

100], we used one hidden layer with sigmoid activation; the output layer used identity (linear) activation, appropriate for a continuous criterion. The number of hidden neurons was set to a small intermediate size (between the number of inputs and the output), following common rules-of-thumb and a brief trial-and-error process to balance prediction accuracy and overfitting risk [

94,

95,

96]. Optimization employed SPSS’s scaled conjugate gradient backpropagation. Model outputs included the network diagram, case-processing summary, and predicted-versus-observed and residual-versus-predicted plots. Independent-variable importance was computed and normalized to assess the relative contribution of PT, PSG, PU, PR, TR, and RE to BI. To ensure robustness, ten MLPs with different random initializations (Networks 1–10 in

Table 7) were trained and evaluated on the hold-out set, and the network with the lowest testing RMSE was subsequently used for the importance analysis.

Comparable to other studies on SEM-ANN modeling in technology-adoption research, to keep matters manageable and stay well within the needed sample size of N = 365 at this exploratory pilot phase of research, we limited ourselves to a single hidden-layer multilayer perceptron neural net architecture which has enough power to model continuous outcomes with small- to mid-sized datasets like ours but with much lower risks of overparameterization [

94,

95,

96], which may come with more complex neural nets with more hidden layers like those with swarm intelligence optimizations commonly applied, for example, to engineering models of outcomes like prediction problems typically found at more applied rather than more basic or foundation research studies akin to ours [

96,

101]. Correspondingly, we chose not to conduct these benchmarks with other machine learning models (such as random forests or support vector machines) because we are principally interested in comparison with the linear SEM model on this particular problem, and because we are using the ANN merely to explore potential non-linear patterns of importance rather than to propose or evaluate these models as tools for either general or specific predictive tasks. Exploring these alternatives would necessarily significantly broaden the technical focus of this manuscript’s contribution to SEM research. This semi-parametric approach combines the explanatory strengths of SEM, used for the evaluation of theoretical models, with the capabilities of the ANN to explore the value of thresholds, curvatures, or interaction-like terms, which could be nonlinearly related to the response, beyond the capabilities of linear models [

96,

101,

102]. The SEM coefficients, inference, or the ANN out-of-sample predictive accuracy, along with its importance, will be presented in the Structural Results section, to contribute to the confirmation of the relevance of the BI determinants (

Figure 2).

We then fitted ten feed-forward multilayer perceptron (MLP) networks on the 70% training split with BI as the dependent variable and PT, PSG, PU, PR, TR, and RE as standardized input covariates. For each run, a different random initialization was used, and the remaining 30% of the sample was held out for testing. Across the ten networks (labeled Network 1–Network 10 in

Table 7), the mean testing RMSE was 0.535 (SD = 0.027), indicating stable prediction accuracy with low variability (coefficient of variation ≈ 5%). The network with the lowest testing error was Network 4 (testing RMSE = 0.500 for 110 test cases), followed by Network 5 (RMSE = 0.503) and Network 8 (RMSE = 0.518). The average training RMSE was 1.969 (SD = 0.058). Testing error was consistently lower than training error, and together with the small dispersion across runs, this pattern suggests no substantial overfitting under the chosen architecture (one hidden layer, sigmoid hidden activation, and identity output).

In terms of the interpretation of the BI latent construct, with an RMSE value of about 0.50, the average prediction error is about one-half standard deviation, which is moderate precision on the individual prediction score, but is adequate for ranking/selection purposes only, not for individuated forecasting techniques. The ANN outcomes are consistent with the SEM in underscoring the concerted, independent predictive value of the same set of BI perceptual variables over time. Network 4, the best-performing model in

Table 7, was selected for subsequent sensitivity and importance analyses.

To validate the SEM results, we also evaluated the importance of variables on the out-of-sample data of the ten multilayer perceptron models with the following parameters (70/30 split; one hidden layer; sigmoid hidden activation; identity output) (

Table 8). The importance scores are scaled on each network, with the average score reported, along with a normalized score in which the importance of perceived transparency (PT) = 100%. In all models, the variables with the highest importance in the prediction of behavioral intention (BI) were trust (TR) and perceived transparency (PT). The mean importance across all models was: PT = 100%, TR = 88%, perceived safety/guardrails (PSG) = 55%, perceived usefulness (PU) = 30%, psychological reactance (RE) = 26%, and perceived risk (PR) = 8%. The importance values were consistent across different random initializations, with TR = 0.75 to 0.98, PSG = 0.36 to 0.81, PU = 0.17 to 0.41. The pattern is consistent with the structural model, with PT and TR having the largest predictive value, followed by PSG, while PU and RE had smaller but still meaningful contributions, but with little predictive value from PR in the ANN stage, consistent with its nonsignificant direct effect in SEM with only a weak indirect effect. The ANN diagnostics show that, inclusive of non-linear and possibly non-compensatory relationships, the perceptions of users’ transparency and trust are the most important, along with visibility of the value. Guardrails are the secondary leverage point, with usefulness important mostly once credibility is signaled, reactance having only a modest role, with risk having only trivial predictive value over and above the other perceptions accounted for. This pattern is consistent with the RMSE analysis, where the network with the best test RMSE was around 0.50, consistent with the dual-pathway account for which the interface cues that increase perceptions of transparency and build trust are the most predictive for GenAI adoption on the problem suite described.

5. Discussion

5.1. Direct Relationships

This structural model highlights the importance of interface-level perceptions for the adoption of GenAI. PT was observed to have the strongest correlation with BI, even greater than the effect sizes of PSG, PU, or other precursors combined. This is in line with user-focused XAI studies, which have found the traceability of reasoning, steps, and sources to be crucial proximal cues predictive of trust and utilization, once salient and well-understood by the end-users (e.g., [

7,

45]). In the current study, the effect size of PT is consistent with the notion that explainability perceptions, over the availability of explanation itself, are the drivers for downstream cognitive evaluations, including trust perceptions, usefulness, or the citizen’s propensity to adopt the technology.

Trust in automation (TR) also had a strong positive correlation with BI, confirming the generality of the result that trust is the proximal correlate of reliance across the board in AI, robotics, and service robots alike (e.g., [

12,

13]). The joint importance of PT and TR indicates strong entwinement between explanation salience and confidence in the relation, with users preferring to enter the relation-cognitive stage if and only if they can see how the system works (PT) and if they trust the system to perform well and genuinely (TR).

A smaller, but significant, association was also found with BI in the case of PSG. This is consistent with the view that visibility of safeguards, refusals, and policy cues affects perceptions of assurance and feelings of vulnerability in those seeking to protect their privacy or prevent harm [

43,

57]. The result is also consistent with the view that the effect of guardrails on system adoption is largely one of signaling the bounds of system acceptability, which is more concerned with signaling that the system will respect those bounds, and hence is theoretically consistent with the pattern we see compared with PT, even if less strong, because the value of the effect is largely one of signaling, which is weaker than the strong signal sent by PT, but consistent with the view that adoption occurs because the system provides assurance, but also because the system provides its users with the necessary explanation regarding how the system operates to be justified in its operation on a daily basis to prevent BI.

PU had only a modest positive effect on BI. This result occupies a middling position in a split literature, wherein, on the one hand, usefulness is seen to play a prominent role in particular areas, while, on the other hand, its effect is diminished once credibility and risk are represented in the model. However, the current study indicates that usefulness provides explanatory value independent of PT, PSG, or TR, implying that users do, in fact, evaluate the system on the basis of both its value proposition and its credibility attributes. The magnitude of the effect is also enlightening, wherein, within contexts of working with competent but sometimes fallible agents, credibility, legibility, and reputation may be seen to carry greater importance than actual performance expectations, particularly with reference to tasks involving reputation or error penalties [

71,

74].

However, neither perceived risk (PR) nor reactance (RE) contributed to the prediction of BI, once the other variables had been controlled for. The nonsignificant direct effect of PR is consistent with interpretations involving the mediator role of trust (risk damages trust, which in turn hurts intent) instead of risk acting alone as an intimidator. It is also consistent with the notion that the salience of risk is highly context-dependent, specifically with the focus of the measure or question asked—from error cost to liability and privacy concerns). There appear to be two interpretations of RE: First: For the predominantly retrospective, real-world-use scenarios described above, GenAI interfaces could occasionally express threats to autonomy strongly enough to establish state-level reactance measures, given that users can easily opt to disregard or opt-out of the recommended guidance provided. Second: While the items taken together assess “such assistants,” they instead tap more broadly into an individual’s tendency to feel annoyance at being directed or limited, which could lack adequate detail to capture specific design-level threats to freedom related to guardrail or nudge designs. The lack of significance of RE supports the idea that under the interface treatments addressed within this study, perceived threat to freedom was probably well below what was needed to induce reactance and that this operationalization of the construct could easily fall somewhere between state-level and design-level reactance notions of constructs like RE. Future research should carefully tease these apart with measures of state-level reactance together with manipulations at the interface level to see if more design-sensitive notions of reactance can instead capture mediation of safety cues on intention directly.

5.2. Mediation Analysis

The mediated model confirms the risk–trust view of GenAI adoption and the respective functions of the two interface levers in the model. To answer the second question, the effect of both PT and PSG was partially mediated by TR on BI, with PT → TR → BI and the paths from both PT and PSG to BI retaining their direct significance. This result supports the view from user-focused XAI that perceptions of explainability are seen as increasing trust largely if they implicate feelings of competency and integrity, with PT influencing trustful enactment of BI on the lines of [

7,

45], who both argued that perceptions of explainability improve trustful usage largely if the explanation impinges on feelings of competency, integrity, or other pseudo-character attributes, with the trust in automation arguing that trust is the proximal, discretionary mediator of adoption, implying that interface levers must be seen to work on the trust mechanism, with traceability or refusals acting on users’ feelings of competency or integrity rather than just informing users about the system, to improve adoption outcomes.

Second, the construct “perceived risk” (PR) also demonstrated indirect-only significant mediation with a non-significant direct effect on BI, with the “full mediation” pattern having clear theoretical interpretation. This indicates that the proposed generalized downside perceptions of privacy risks or error costs of influencing BI are mostly mediated by trust, meaning that the deterrent is not about discouraging the service itself but about the undermining of trust. A design implication of the study is the importance of turning the management of risk into trust-building cues, instead of trying to reduce the perceptions of risk on their own [

11,

49].

Thirdly, the paths on reactance-based hypotheses were always non-significant. Given existing findings that social mimicry, coercive monitoring, or restricted choice can provoke freedom-threat responses, the result indicates that the interface in the current study did not trigger the reactance process strongly enough to propagate the effect to the intended target, intention [

16,

19,

21]. There are two possible interpretations of the result. Either the PT/PSG implementations de-threatened agency, perhaps by requiring clear rules but being seen, rather than restrictive, or the reactance process is context-dependent, manifesting in designs that emphasize human qualities, more restrictive refusals, or surveillance framing. Theoretical implication would be that reactance is just one particular type of process involved in the adoption of GenAI that is highly design-dependent, having value only if seen in the context of explicit preventive EPM, but not otherwise [

19,

47,

52].

A small total effect with a modest direct effect on BI was found for PU, with no significant mediation effect involving TR (PU → TR → BI: p = 0.055, marginal at best). This subtle complexity resolves the mixed support in the literature, with instrumental value being important but, with the underlying credibility paths specified, perhaps having only modest, or trivial, indirect value in influencing BI, unless the task is high-stakes or the claim of competence is ambiguous.

5.3. SEM-ANN Synthesis

The semi-parametric SEM-ANN model provides insights on how the interface signals are linked with adoption and the importance of the signals once non-linear, possibly non-compensatory relationships are enabled between them. Regarding the SEM part, trust was always carrying the effect of design perceptions to the intention: perceived transparency (PT) had partial mediated relationships via trust, while for both perceived safety/guardrails (PSG) and perceived risk (PR), there were indirect-only, fully mediated relationships via trust. There were no mediated relationships involving psychological reactance (RE). All these result support the risk–trust conduit due to the involvement of trust between the variables, traceability on trust conduit due to the involvement of traceability, and perhaps an inactive freedom-threat dynamics process on the current interface map.

The conclusions reached by the ANN are sustained by the following structure from the predictive view. The average value of the hold-out RMSE over the ten multilayer perceptron models (0.500, with SD = 0.027) indicated stable, moderate prediction accuracy on the individual level of behavioral intention, with the best iteration also achieving 0.500, just below the baseline average. The sensitivity analysis revealed PT, followed by the importance of trust (TR) normalized to 100% and 88%, respectively, followed by the mid-tier effect of the importance of PSG, followed by the PU importance of 30% with the smallest, but still incrementally significant, importance of RE = 26%, with the addition of PR = 8% having only trivial predictive value beyond the inclusion of the other perceptions. Taken together, the SEM mediation and ANN importance profiles converge on the view that the appropriation mechanism is trust-focused, wherein TR, transparency, or the lack thereof, is the decisive factor, followed by the importance of usefulness, followed by the generalized risks, but the latter exercising its influence largely on TR, rather than on the adjustment of intent itself.

In terms of theoretical implications, there is reason to distinguish between PT and PSG on theoretical grounds. Despite common aggregation into “transparency,” the current findings reveal the presence of paths that are almost but not completely identical: traceability/comprehension for PT and assurance/boundary interpretation for PSG. Both are primarily trust-calibrating, consistent with user-focused XAI interpretations that perceived explainability needs to attain salience thresholds before achieving fall-back, with assurance cues fixing points for credibility. Second, the only indirect pattern supported by PR situates trust itself within the immediately decisive role in the benefit–risks calculus, believing risk will deter primarily by undermining trust itself. Third, the lack of reactance support indicates boundary constraints on freedom-threat explanation, reactance being instead design-dependent, rather than generally applicable, becoming consequential under stronger autonomy-threat framings (e.g., coercive monitoring, heavy anthropomorphic mimicry) documented elsewhere.

Taking a closer look at perceived risk (PR), it appears that structural equation modeling (SEM) and artificial neural networks (ANN) find complementary rather than contradictory results about it. On analyzing using the SEM model, PR shows an indirect-only effect on intention mediated by trust, which fits well with risk–trust–intention models where high perceived risk chiefly affects adoption negatively through lower trust rather than directly affecting intention. On the other hand, using an ANN model, PR receives relatively low normalized importance (8%) when considering PT, TR, PSG, PU, and RE simultaneously; hence, concerning a general-use scenario for GenAI applications where diverse applications are involved, PR appears relatively insignificant compared to other factors related to transparency and trust perceptions for out-of-sample predictive models rather than models inside samples. These findings together imply that PR tends to work like an antecedent to trust rather than an actor on intention onstage in this particular sample, probably because of moderate concerns rather than specific ones involved diffusely; hence, these findings can neither refute nor state conclusively any specific models related to detailed segment designs with or without expertise due to of sample unfitness, but rather seem plausible when assuming that specific applications would receive relatively higher concerns of perceived risk compared to general-use applications like those of GenAI assistance systems. Although structural paths and mediation patterns are grounded in theory, empirical estimates involve cross-sectional and retrospective self-report measures. Therefore, reported effects should be viewed only as directional associations but not causal paths. There may still be bidirectional influences among perceived transparency, safety, risk, trust, and prior uses of GenAI, which can only be addressed through longitudinal or experimental studies.

6. Practical Implications

The results suggest the existence of pervasive trust-building paths to the adoption of GenAI, with the main drivers being perceived transparency (PT) and perceived safety/guardrails (PSG), supported by—rather than instead of—perceived usefulness (PU). The role played by perceived risk (PR) remains mediated by trust, while reactance is significant only in the more autonomy-threatening design conditions, with the following steps taken by stakeholders.

Transparence on result-focused assurance, over broad disclosure, must be the priority. Best practices for standards must differentiate between traceability—ability to trace steps, trace sources, and trace well beyond the limit—and guardrails—scope, refusal reasons, and notices on policy matters. Certification or audit processes can evaluate traceability and guardrails formally for their respective contributions to trust-building. Since trust is the operative factor in risk, risk communication must be refined—to specific, brief notices linked with mitigation strategies, rather than broad warnings, which can reduce confidence without enhancing understanding. When GenAI is involved in public services, explanation on request, with accessible, understandable reasons, must be required, with assurance by default, in view of equitable adoption.

Roadmap design allocations can focus on legibility aspects (reasoned justifications, citations, links to checked facts, and “why this answer” areas) and assurance aspects (definition of scope, refusal messages, safety/privacy overviews, and data management controls). Consider these UX basics, not optional help text or nice-to-have UI polishing. The sensitivity of the ANN adoption model indicates the biggest adoption benefits will come from PT improvements, with trust also highly beneficial, followed by the secondary tactic of PSG, with PU messages working better if credibility indications are already in place. Instrument and A/B test trust diagnostics on task outcomes, perceived explainability, and perceived safeguard clarity, looking out for autonomy-threatening cues (overly restrictive nudges) that may provoke reactance or resistance from users who feel their agency has been usurped.

When incorporating GenAI into the curriculum, link skill development with the literacies of transparency (evaluate reasoning and sources) and assurance (evaluate limitations and refusals). Classroom policies need to reflect the rules of the PSG, specifying acceptable uses, the boundary conditions of error, and academic integrity in the interface paradigm itself, perhaps with templates defining the bounds of scope and refusal logic. The role of PU, since it makes contributions only after the formation of credibility, must be featured in the credible workflow, “explain → verify → apply,” before the efficiency application itself.

7. Conclusions, Limitations, and Future Directions

This work moves the frontier on a dual-path model of GenAI adoption, wherein interface-level cues primarily influence intention via trust. In the SEM, perceived transparency (PT) was the strongest direct predictor of intention, followed by the strong direct impact of trust (TR). The effect of perceived safety/guardrails (PSG) was more modest, yet significant, with the inclusion of perceived usefulness (PU) adding modestly to the model. Neither perceived risk (PR) or reactance (RE) explained unique variance beyond other variables specified in the SEM. The set of mediated models revealed that PT, and the effect of PSG, operated partially via trust, with the effect of perceived risk operated fully/indirectly via trust, confirming the risk-to-trust mechanism proposed. The mediational paths involving reactance appreciated none of the hypothesized relationships, failing to support the proposed relationships fully. The diagnostics on the Stage 2 ANN supported the structural modeling, wherein PT, followed by TR, provided well-driven predictive priority, with the inclusion of PSG, PU, and RE offering some modest, incremental predictive boost, with the inclusion of PR offering some slight predictive value beyond the other variables.

To move the existing body of work forward, a number of promising lines of work are proposed. It relied on a stratified purposive quota sample recruited using an online panel composed of EU citizens with previous experience with GenAI systems. Thus, external validity factors can only relate to circumstances with parallel regulatory and cultural factors; it cannot inform or guide studies among those unexposed to systems like GenAI. Consistency among respondents was found to differ with regard to experience level (with considerable numbers of low- or moderate-experience holders paralleled with more expert types); this could dampen specific-domain patterns identifiable among those expert or so-called “power” system-users. Still, for this specific article’s purposes, the focus was on how well the core perceptual pathway (PT, PSG, PU, PR → TR/RE → BI) model could work together with or benefit from using structural equation modeling–artificial neural network (SEM–ANN) hybrids which were necessary to explain and show effects rather than to exhaustively probe all possible subgroup differences among EU system users interested in or using GenAI systems for their own benefits or purposes. Second, this study relied only on a single wave of cross-sectional, self-report data to infer perceptions and usage over time, which limited causal interpretations. Specifically, these measures assess intention at a particular point in time with no distinction between those who maintained, escalated, or discontinued using GenAI systems once they were adopted for initial purposes. Future studies would benefit from using experience-sampling designs or other techniques that would track these samples longitudinally with multiple points separated to differentiate initial adopters versus persistent patterns (e.g., sustained usage or dropouts). Incorporating these longitudinal constructs with field experimentation of cues of transparency would significantly clarify matters concerning cause and effect. Field A/B tests with independent manipulation of transparency (traceability, source links and step-by-step rationales), CRLS/SG, and guardrails (scope boundaries, refusal rationales and policy prompts), may help elucidate thresholds, diminishing marginal returns or context-dependent trade-offs between them. Panel studies alongside the A/B work would help illustrate the unfolding perceptions of PT, PSG, risk, trust, and reactance over time, with longitudinal study design allowing for the discrimination between study variables’ treatment periods or A/B groups. Risk and agency are due for some attention as intervening variables, with the treatment instead taken on its own multifaceted terms, rather than an oversimplified one-dimensional construct, with attention to the particular facets of each, specifically, on the side of risk [

11,

49,

75]. Since freedom-threat responses are design-sensitive, simultaneous manipulations of trait reactance and autonomy threats (e.g., preventive or developmental framing, choice architectures, override controls) can help disambiguate the activation of the freedom–trust link and the role of agency-restoring attributes in its process [

32,

75]. Future models will require the inclusion of outcomes other than intention, namely, the quality of reliance: well-calibrated trust, second opinions, error correction, and human–AI cooperation effectiveness. These outcomes are relevant to analysts concerned with policy/behavioral impacts on safety, who may identify conditions wherein greater system openness leads to over-reliance, unless coupled with well-engineered safety bounds or just-in-time warnings with adjustable levels over time. The predictive pathway will be improved. Side by side with single-hidden-layer MLP, compare GBM, GAM, or calibrated logistic/ordinal models with respect to repeated k-fold CV, temporal holdouts, or learning curves [

35]. Post hoc methods (permutation importance, partial dependencies, and cumulative local effects) or sparse additive models can help integrate the sometimes-conflicting needs for accuracy and explainability, while SEM with its potential for interactions in the underlying constructs, or LMS/PLS product indicators, can attempt to probe the non-linear synergy that the ANN model implies.

In conclusion, the implications of our discoveries outline the promise that exists within complex systems: if computers can reveal their process and stick to their bounds, humans will help them out along the way, meeting them halfway. The answer, then, to the question of trust is neither on nor off but rather the road we walk, guided by reason, lined with the gentle hand of human moderation. A future of system design holding to these lines—showing the user just enough to understand the process, stopping just in time for the user to feel secure—may propel GenAI from an intelligent solution to a trusted sidekick in the work we do each day. When these solutions are able to speak more clearly, to say “no” in due time, perhaps we will too, learning to target better, build higher, with the confidence of silence in the process we create.