1. Introduction

Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) refers to a group of chronic inflammatory conditions that affect the gastrointestinal (GI) tract. The two predominant forms of IBD are ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease (CD). UC is typically localized to the innermost mucosal layer and predominantly occurs in the distal colon. In contrast, CD can involve multiple regions of the GI tract and is characterized by inflammation that penetrates deeper tissue layers, including the muscular layer [

1,

2]. Although extensive studies have been conducted over the past decades, the precise cause and pathogenesis of IBD remain incompletely understood. Individuals genetically susceptible to IBD are thought to possess immunological and physiological traits that trigger an aberrant immune response, leading to unrelenting inflammation when exposed to environmental stimuli that challenge immune homeostasis [

2,

3].

Conventional pharmacotherapy for IBD includes small-molecule drugs and biologics aimed at controlling inflammation and prolonging remission. Standard treatments such as aminosalicylates, corticosteroids, and immunosuppressants are often associated with limited anti-inflammatory efficacy or substantial adverse effects. Biologics, including anti-TNF-α agents, offer improved therapeutic outcomes but can still pose challenges related to safety, resistance, patient compliance, and medical cost [

4,

5]. More recently, small-molecule agents such as Janus kinase inhibitors and sphingosine-1-phosphate receptor modulators have been introduced, classified pharmacologically as immunosuppressants or immunomodulators. Despite these advances, issues like systemic toxicity, drug resistance, and parenteral administration continue to hamper long-term therapeutic success [

6,

7].

Drug repurposing (DR), also known as drug repositioning, is a strategy that seeks to identify new indications for existing or previously withdrawn drugs [

8,

9]. Given the high cost, failure rates, and extended timelines of de novo drug development, DR has garnered increasing interest, particularly for diseases lacking effective treatments. Repurposed drugs benefit from known pharmacokinetic profiles and established safety data, enabling faster and less expensive development. However, this approach is not without its challenges, including regulatory and medical hurdles [

10]. In the case of DR for the treatment of IBD, colon-specific drug delivery has been explored as a means to improve the safety and efficacy of repurposed therapeutics [

11,

12].

Colon-specific drug delivery (CSDD) can be achieved through prodrug design or pharmaceutical formulations, allowing the active drug to bypass degradation and absorption in the upper GI tract and be released predominantly in the large intestine [

13]. This site-specific delivery increases colonic drug concentration while minimizing systemic exposure, which enhances therapeutic effects and reduces side effects. CSDD is therefore particularly beneficial for diseases primarily affecting the large intestine [

13,

14]. For instance, mesalazine-based therapies are chemically modified or encapsulated to ensure delivery from the ileum to the distal colon [

15]. Recent efforts have applied this strategy to DR, exploiting the advantages of CSDD to enhance efficacy and safety of repurposed drugs [

11,

16].

Sulfonylureas are orally active agents used in the management of type 2 diabetes mellitus. These compounds act on sulfonylurea receptors associated with ATP-sensitive potassium (KATP) channels, promoting insulin secretion by depolarizing pancreatic beta cells through calcium influx [

17]. Notably, KATP channels are also expressed in monocytes and macrophages, where they modulate inflammatory responses via the MAPK and NF-κB signaling pathways. Accordingly, sulfonylureas have been reported to exhibit anti-inflammatory effects by attenuating cytokine release under both diabetic and non-diabetic conditions [

18,

19,

20,

21,

22]. Furthermore, some sulfonylureas can inhibit inflammasome activation independently of KATP channel blockade by binding to sulfonylurea receptors [

23,

24]. Structural analysis suggests that the sulfonylurea moiety itself may underlie this activity, with variations in potency influenced by drug-specific chemical features [

25].

Carbutamide (CBT), the first orally available anti-diabetic sulfonylurea, was originally derived from antimicrobial sulfonamides [

26,

27]. As a first-generation agent, CBT has been superseded by more modern sulfonylureas such as gliclazide, glipizide, glibenclamide, and glimepiride [

26]. In addition to its potential anti-inflammatory effects, CBT and other sulfonylureas have been shown to inhibit peptide transporter 1 (PepT1), a transporter implicated in intestinal inflammation [

28]. Inhibition of PepT1 has demonstrated efficacy in ameliorating experimental colitis by reducing uptake of pro-inflammatory peptides [

29,

30,

31,

32]. In this study, CBT-despite its discontinued clinical use due to cases of severe bone marrow and kidney toxicity reported in post-marketing surveillance—was selected for repurposing as an anticolitic agent using a colon-specific prodrug strategy [

33]. This decision was based on three key factors: (1) CBT is expected to possess anti-inflammatory activity through inhibition of PepT1 in addition to inhibition of inflammasome and KATP channels, (2) CBT contains an aniline group suitable for azo-bond formation—a validated approach for colon-specific delivery [

34], and (3) CBT is more hydrophilic than other sulfonylureas, which favors prodrug design for colonic delivery. Furthermore, major adverse effects associated with repurposing of CBT as an anti-IBD drug, including hypoglycemia and bone marrow suppression, may be mitigated through CSDD, potentially improving its safety profile. Notably, inhibition of inflammasome or PepT1 typically requires higher drug concentrations than KATP channel blockade, which are unlikely to be reached in plasma following standard oral dosing of sulfonylureas [

25,

28].

To this end, CBT was chemically linked to the anti-inflammatory agent mesalazine (5-ASA) via an azo bond, forming CBT azo-linked with salicylic acid (CAA) designed to deliver both agents to the large intestine. The colonic delivery performance of CAA was evaluated in parallel with sulfasalazine (SSZ), a clinically approved colon-specific 5-ASA prodrug [

35]. While olsalazine, balsalazide, and sulfasalazine (SSZ) are all clinically relevant azo-prodrugs of 5-ASA, previous comparative studies have shown that their therapeutic efficacy is largely similar [

35]. The therapeutic efficacy of CAA was assessed in a dinitrobenzene sulfonic acid (DNBS)-induced rat colitis model and benchmarked against SSZ. Additionally, potential synergy between CBT and 5-ASA was explored via intracolonic administration of the individual drugs and their combination. Finally, systemic safety was examined by comparing CBT plasma concentrations and hypoglycemic responses following oral administration of CBT versus CAA.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

Salicylic acid and DNBS were sourced from Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc. (Waltham, MA, USA), while CBT was obtained from BLD Pharmatech Ltd. (Shanghai, China). 5-ASA, SSZ and Fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-dextran (average molecular weight 4000) were supplied by Sigma-Aldrich Chemical Co. Inc. (St. Louis, MO, USA). Valacyclovir (VCV) was obtained from Ambeed, Inc. (Arlington Heights, IL, USA). Sodium nitrite (NaNO2) and sulfamic acid (HOSO2NH2) were purchased from Tokyo Kasei Kogyo Co. (Tokyo, Japan). Solvents used for reactions and those of HPLC grade were procured from Junsei Chemical Co. (Tokyo, Japan) and DAEJUNG Chemicals & Metals Co., Ltd. (Gyeonggi-do, Republic of Korea), respectively. The cytokine-induced neutrophil chemoattractant-3 (CINC-3) ELISA kit was obtained from R&D Systems (Minneapolis, MN, USA). Unless otherwise specified, all chemicals used in this study were of commercially available reagent grade. TLC analysis was performed using silica gel F254s plates (Merck Millipore, Burlington, MA, USA), and spot detection was carried out under UV light at 254 nm. High-resolution LC-MS/MS spectra were acquired using a ZenoTOF 7600 system (SCIEX, Framingham, MA, USA). Infrared spectra were recorded using a Varian FT-IR spectrophotometer, and proton nuclear magnetic resonance (1H-NMR) spectra were obtained with a Varian NMR instrument (Palo Alto, CA, USA). Chemical shifts in the 1H-NMR spectra are reported in parts per million (ppm) relative to tetramethylsilane as the internal standard.

2.2. Synthesis of CBT Azo-Linked with Salicylic Acid (CAA)

To CBT (271 mg) dissolved in pre-cooled 5 M HCl (15 mL), sodium nitrite (NaNO2, 103 mg) was gradually introduced under continuous stirring on ice for 30 min. Sulfamic acid (49 mg) was subsequently added to remove excess nitrite. In parallel, salicylic acid (138 mg) was solubilized in 1 M NaOH (5 mL), and the resulting solution was subsequently introduced into the diazonium mixture while maintaining the pH within 8–9 at a temperature of 20–25 °C for 6 h. Once the reaction was complete, the mixture was subjected to centrifugation at 3000× g for 10 min. The precipitate was rinsed three times with chilled distilled water and then dried under reduced pressure to obtain 5-((4-(N-(butylcarbamoyl)sulfamoyl)phenyl)diazenyl)-2-hydroxybenzoic acid (CBT azo-linked with salicylic acid, CAA) as reddish brown powder. Synthesis of CAA was verified using FT-IR, 1H-NMR spectroscopy, and time-of-flight mass spectrometry. CAA (M.W.: 420.44); Yield: 78%; mp: 186 °C (decomp.); FT-IR (nujol mull), νmax (cm−1): 1672 (C=O, carboxylic and sulfonylurea, broad); 1H-NMR (500 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ = 8.39 (s, 1H), 8.11 (d, J = 9 Hz, 1H), 8.08 (d, J = 8.5 Hz, 2H), 8.03 (d, J = 8.5 Hz, 2H), 7.19 (d, J = 8.9 Hz, 1H), 2.95 (m, 2H), 1.31 (p, J = 7 Hz, 2H), 1.18 (sx, J = 7.3 Hz, 2H), 0.80 (t, J = 7.3, 3H); [M+H]+: m/z = 421.1177.

2.3. HPLC Analysis

The HPLC system consisted of a Gilson model 306 pump, a 151 variable UV detector, and a model 234 autoinjector (Gilson, WI, USA). Chromatographic separation was carried out using a Symmetry C18 column (250 mm × 4.6 mm, 5 μm; VDS Optilab Chromatographietechnik GmbH, Berlin, Germany). Prior to HPLC injection, all samples were passed through 0.45 μm membrane filters. The mobile phase A was composed of distilled water and acetonitrile in a 6:4 volume ratio, while mobile phase B consisted of 1.0 mM phosphate buffer (pH 7.0), supplemented with 0.5 mM tetrabutylammonium chloride, and mixed with ACN in an 8.5:1.5 volume ratio (v/v). The chromatographic run was conducted at a fixed flow rate of 1 mL/min. Ultraviolet detection was carried out at wavelengths of 270 nm for CBT and 300 nm for 5-ASA, with the sensitivity adjusted to AUFS 0.01. Under these analytical settings, retention times were recorded as 6.5 min for CBT (in mobile phase A) and 9.5 min for 5-ASA (in mobile phase B).

2.4. Distribution Coefficient

Following the dissolution of CBT and CAA (1.0 mM) in 10.0 mL of 1-octanol pre-equilibrated with pH 6.8 phosphate buffer saline (PBS), an equal volume of the buffer (10.0 mL), which had been pre-saturated with 1-octanol, was layered onto the organic phase. The resulting biphasic system was gently agitated on an orbital shaker at 200 rpm for 12 h and then allowed to stand at 25 °C for 4 h to ensure complete phase separation. Absorbance at 270 nm was measured to determine the amount of each compound remaining in the 1-octanol layer using a UV-Vis spectrophotometer (Shimadzu, Kyoto, Japan). The distribution coefficient (log

D6.8) was derived from the initial concentration in the organic phase (C

O), the equilibrium concentration in the aqueous phase (C

W), and the concentration in the 1-octanol phase at equilibrium (C

Oc).

2.5. Chemical Stability

To evaluate the chemical stability of CAA, the compound (0.1 mM) was incubated for 10 h in two different buffer systems: an HCl-NaCl buffer at pH 1.2 and PBS. The drug concentrations over time were analyzed by HPLC to monitor potential degradation.

2.6. Animals

Seven-week-old male Sprague-Dawley (SpD) rats (Samtako Bio Korea, Gyeonggi-do, Republic of Korea) were maintained at the animal facility of Pusan National University (Busan, Republic of Korea) under standardized environmental conditions, including regulated temperature, humidity, and a 12-h light/dark cycle. All experimental procedures involving animals were reviewed and approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Pusan National University (PNU-IACUC), in accordance with ethical guidelines and scientific care standards (Approval No: PNU-2021-2942; Approval data: 23 March 2021).

2.7. Drug Release in Rat Small Intestinal and Cecal Contents

Male SpD rats were killed via carbon dioxide asphyxiation. Following euthanasia, a midline incision was performed on the abdomen to access the GI tract. The luminal contents of the small intestine and cecum were individually extracted and suspended in PBS to create a 20% (w/v) suspension. To maintain anaerobic conditions, cecal samples were processed inside a nitrogen-filled bag (AtmosBag, Sigma-Aldrich, MO, USA). A 2.0 mM solution of CAA, prepared in 3.0 mL of PBS, was mixed in equal parts (3.0 mL) with either intestinal or cecal suspensions and incubated at 37 °C. For cecal samples, the incubation was conducted under nitrogen atmosphere. At pre-determined time points, 0.5 mL of the mixture was withdrawn and centrifuged at 10,000× g for 10 min at 4 °C. From the resulting supernatant, 0.1 mL was transferred to 0.9 mL of MeOH, mixed using a vortex mixer, and centrifuged again under the same conditions. The final supernatants were filtered through 0.45 μm pore-size membrane filters, and CBT concentrations were quantified using HPLC.

2.8. Transport Assay Using Everted Gut Sacs of Rats

Male SpD rats underwent a 24 h fasting period, during which water was available without restriction. Rats were killed using carbon dioxide asphyxiation, and the jejunum (6 cm) were excised immediately. The jejunal was used for transport assay of CBT and CAA at 1.0 mM, respectively. The intestinal segments were well-rinsed with pre-warmed (37 °C) Krebs solution (120.0 mM NaCl, 5.0 mM KCl, 2.0 mM CaCl

2, 1.0 mM MgCl

2, 5.5 mM HEPES, and 1.0 mM

d-glucose) adjusted to pH 7.4 and filtered through a 0.45 μm membrane filter for sterilization. The intestinal segments were gently everted using glass rods and forceps, and the apical surface was washed with the pre-warmed Krebs solution. One end of each segment was tied with thread, and the sac was filled with pre-warmed Krebs solution (600 μL), which was placed into a 15 mL tube containing pre-warmed Krebs solution (8 mL), ensuring that the sac was submerged to the solution so that the level of the internal solution became same with that of external solution. After securing 50 μL of the internal solution 10 min later as a blank used for background correction in UV absorption analysis, based on a preliminary experiment as described in

Supplementary Information S1, the opposite end of the tube was loosely tied with thread and affixed to the outer surface of the tubing to hold the sac in place during the ex vivo studies. The assembled tubes were maintained at 37 °C, and aliquots (50 µL) were withdrawn from the basolateral (inner) side at scheduled time points, with an equal volume of fresh Krebs solution replenished each time. For quantitative analysis of CBT and CAA in the transport assay using jejunal segments, the samples and the blank obtained were mixed with MeOH (575 μL), centrifuged at 10,000×

g at 4 °C for 10 min. The concentrations of CBT and CAA present in the supernatants were quantified at 270 nm (for CBT) and 355 nm (for CAA) using a UV-Vis spectrophotometer (Shimadzu, Kyoto, Japan).

For the assessment of intestinal barrier integrity, an additional assay was conducted using FITC-dextran (100 μM) co-applied with either CAA (1 mM) or CBT (1 mM) to the apical side under the same experimental conditions as described in

Supplementary Information S2.

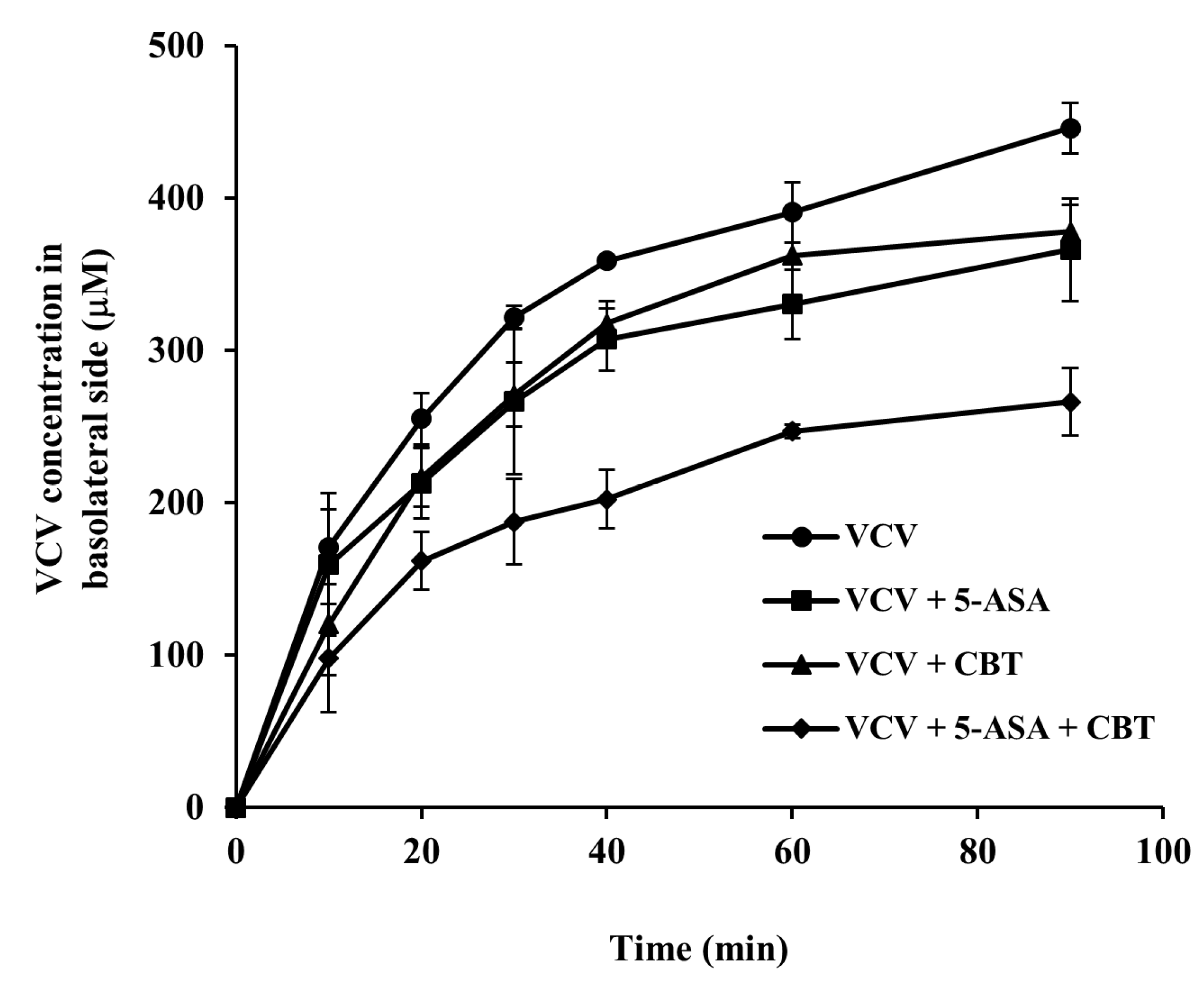

2.9. Competition Study Using Everted Gut Sacs of Rats

Male SpD rats underwent a 24 h fasting period, during which water was available without restriction. Rats were killed using carbon dioxide asphyxiation, and distal colon (6 cm) were excised immediately. The colonic segments prepared and set as in

Section 2.8 were used for competition study for transport via pepT1 using the pepT1 substrate VCV (0.5 mM) in the presence of 5-ASA or/and CBT (each at 5.0 mM). For quantitative analysis of VCV in the competitive study, the samples obtained from the basolateral side (50 µL) at scheduled time points were subjected to ethylacetate (EA) extraction to remove CBT, which interfered with the fluorescence analysis of VCV, and the aqueous layers isolated (25 µL) were mixed with MeOH (545 µL), centrifuged at 10,000×

g at 4 °C for 10 min. VCV concentrations in the collected supernatant samples were determined at 280 nm (excitation)/370 nm (emission) using a fluorescence spectrophotometer (RF-6000, Shimadzu, Kyoto, Japan), following acidification of the supernatant (500 µL) with 1 M HCl (25 µL) [

36]. FITC-dextran transport assay was conducted in the presence of CBT, 5-ASA, and CBT + 5-ASA under the same experimental conditions to confirm that the treatments did not affect epithelial barrier integrity as described in

Supplementary Information S3.

2.10. Determination of Drug Concentration in Blood and Cecum

Male SpD rats were subjected to a 24 h fasting period, during which they had free access to water. Each rat received one of the following oral treatments via gavage: CBT (20.4 mg/kg, corresponding to 31.5 mg/kg of CAA), CAA (31.5 mg/kg, equimolar to 30.0 mg/kg of SSZ), or SSZ (30.0 mg/kg). All compounds were suspended in 1.0 mL of PBS prior to administration. At 2, 5, and 8 h post-dosing, whole blood was obtained through cardiac puncture. Plasma was isolated by centrifuging the samples at 10,000× g for 10 min at 4 °C. To measure the plasma concentrations of CBT, 0.1 mL of plasma was combined with 0.9 mL of MeOH, vortex-mixed briefly, and centrifuged again under the same conditions. The supernatants were filtered through 0.45 μm membrane filters, and 20.0 μL aliquots were injected into the HPLC system to quantify concentrations of CBT. For analysis of drugs’ distribution in the cecum, SSZ (30.0 mg/kg) and CAA (31.5 mg/kg) were orally administered as PBS suspensions. At 2, 5, and 8 h post-administration, cecal contents were excised and suspended in PBS to create 10% (w/v) homogenates. After centrifugation (10,000× g, 10 min, 4 °C), 0.1 mL of the supernatant was mixed with 0.9 mL of MeOH, followed by vortexing. The solution was filtered through a 0.45 μm membrane filters, and aliquots (20.0 μL) were injected into the HPLC system to quantify concentrations of CBT and 5-ASA.

2.11. Determination of Blood Glucose Concentrations

Male SpD rats underwent an 18 h fasting period with unrestricted access to water. After receiving CBT (122.4 mg/kg) or its equimolar dose of CAA (190.5 mg/kg), each dissolved in 1.0 mL of PBS, blood glucose concentrations were assessed at appropriate time intervals. For this assessment, blood samples were collected from the murine tail vein. Briefly, anesthetized rats were firmly restrained to ensure clear visualization of the distal tail vein. The tail was thoroughly disinfected with alcohol, and the vein was punctured directly with a syringe needle, which was inserted in an upward direction, following the vessel’s path. The syringe plunger was slowly retracted to prevent venous collapse. After obtaining the desired volume of blood, the needle was removed, and the puncture site was compressed with gauze until hemostasis is achieved. The animals were then returned to their cages and carefully monitored for any signs of distress. Glucose levels were determined using the CareSens N Premier monitoring device (i-Sens Inc., Seoul, Republic of Korea), following the protocol recommended by the manufacturer.

2.12. DNBS-Induced Rat Colitis

Experimental colitis was established in rats following a previously reported method [

37]. In short, male SpD rats were subjected to 24 h fasting with unrestricted access to water. Anesthesia was induced using isoflurane (Hana Pharm, Hwaseong, Republic of Korea) delivered through the Small Animal O

2 Single Flow Anesthesia System (LMS, Pyeongtaek, Republic of Korea), with concentrations set at 3% for induction and maintained at 2.5% using 1 L/min of oxygen. Once anesthesia was confirmed by lack of response to tactile stimulation, a 2 mm outer-diameter rubber cannula was gently inserted into the rectum, positioning the tip approximately 8 cm from the anus at the level of the splenic flexure. A solution of DNBS (48.0 mg in 0.4 mL of 50% ethanol in water) was then administered through the cannula.

2.13. Evaluation of Anticolitic Effects

Two separate animal experiments were conducted to evaluate the therapeutic effects of various treatments against colitis. Treatment groups for the two animal experiments are shown in

Supplementary Information S4. Three days after the induction of inflammation, colitic rats were medicated with each drug once per day via oral or rectal route, and the anticolitic effects were evaluated 24 h after receiving the medication. Colonic damage scores (CDS) were assigned based on a modified scoring system, in which 0 indicated normal tissue appearance; 1, localized hyperemia without ulceration; 2, linear ulcers with minimal inflammation; 3, a 2–4 cm region of ulceration and inflammation; 4, the same extent of inflammation with serosal adhesions to adjacent organs; and 5, the presence of strictures, multiple serosal adhesions involving several intestinal loops, and diffuse inflammation over 4 cm. For evaluation of myeloperoxidase (MPO) activity in inflamed colonic tissue, distal colon segments (4 cm) were finely chopped and transferred to tubes containing 1 mL of hexadecyltrimethylammonium bromide (HTAB) buffer (0.5% HTAB in 0.05 M phosphate buffer, pH 6.0). The samples were homogenized on ice using a T 10 basic ULTRA-TURRAX

® homogenizer (IKA Werke GmbH & Co. KG, Staufen im Breisgau, Germany). The homogenizer was rinsed with additional HTAB solution, and the pooled homogenate was diluted to a final concentration of 100 mg tissue/mL. The mixture was then centrifuged at 10,000×

g at 4 °C. A 0.1 mL aliquot of the resulting supernatant was mixed with 2.9 mL of 0.1 M phosphate buffer (pH 6.0) containing o-dianisidine (0.3 mg/mL) and hydrogen peroxide (0.01%). The absorbance change at 460 nm was recorded for 5 min at 25 °C using a UV spectrophotometer (Shimadzu, Kyoto, Japan). One unit of MPO activity was defined as the amount of enzyme that catalyzes the degradation of 1.0 μmol of hydrogen peroxide per minute at 25 °C.

2.14. ELISA for CINC-3

Quantification of the pro-inflammatory chemokine CINC-3 in inflamed distal colonic tissue was carried out using enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) kits. Tissue samples from the distal colon were finely chopped in potassium phosphate buffer (pH 6.0), mechanically homogenized, and subsequently subjected to centrifugation at 10,000× g for 10 min at 4 °C. ELISA procedures were conducted in accordance with the protocols provided by the manufacturer.

2.15. Data Analysis

Data are presented as mean values accompanied by standard deviations (SD). Statistical comparisons among multiple groups were performed using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA), followed by Tukey’s post hoc test. For CDS analysis, the non-parametric Mann–Whitney U test was employed. A p-value below 0.05 was considered indicative of statistical significance.

4. Discussion

CBT, though no longer in clinical use, is an orally active first-generation sulfonylurea anti-diabetic agent [

17,

27]. Based on accumulating evidence that sulfonylureas exhibit anti-inflammatory properties [

19], CBT was considered a candidate for therapeutic repurposing as an anti-inflammatory agent for the treatment of IBD. To facilitate this repurposing, a colon-specific prodrug strategy was adopted.

A colon-specific derivative of CBT was synthesized by linking it to salicylic acid through an azo bond, forming CBT azo-linked with salicylic acid (CAA). This azo linkage, commonly used in prodrug design for compounds containing an aniline structure like CBT, is well established for its selective activation in the colon [

13,

44]. This structural modification enables CAA to release both CBT and 5-ASA specifically in the large intestine through microbial reduction of the azo bond by colonic azo reductases [

13]. Our findings confirmed that the azo bond in CAA remained intact in the small intestine and acidic conditions, but was effectively cleaved in the cecal environment, fulfilling a key requirement for colon-selective activation [

13]. Additionally, azo linkage with SA significantly increased the hydrophilicity of CBT, as reflected by a lower log D

6.8 value for CAA. This enhanced polarity, attributed to salicylic acid’s hydroxyl and carboxyl groups, likely contributed to the reduced passive transport of CAA across the intestinal wall, as demonstrated by ex vivo transport studies using the jejunum isolated from rats. These physicochemical and transport characteristics align with our in vivo data, which showed that CAA reached the cecum intact and efficiently released 5-ASA at levels comparable to those achieved by SSZ, a clinically used colon-specific prodrug of 5-ASA [

4].

The design of this colon-specific prodrug was intended not only to enhance the local activity of CBT in the colon, but also to promote therapeutic cooperation with 5-ASA in suppressing colitis. Supporting this concept, our in vivo results demonstrated that orally administered CAA alleviated colonic inflammation and tissue injury more effectively than SSZ or a physical mixture of CBT and 5-ASA. This suggests that the therapeutic advantage of CAA over SSZ stems from cooperative interplay between its two active components specifically delivered to the target site. The cooperative action was further supported by rectal co-administration studies, where the combination of CBT and 5-ASA showed greater efficacy in reducing rat colitis than monotherapies with either compound alone.

Interestingly, when orally given as a simple mixture, CBT and 5-ASA failed to show significant protective effects, implying that the CAA-mediated therapeutic enhancement is closely related to local action resulting from site-specific release of CBT and 5-ASA within the colon. Therefore, we propose that the combined therapeutic efficacy may be partially mediated by cooperative inhibition of PepT1, a transporter that is overexpressed in the colonic epithelium of IBD patients and believed to facilitate uptake of bacterial pro-inflammatory peptides [

29,

32,

45]. Our study found that both CBT and 5-ASA suppressed transport of VCV, a substrate of PepT1, across the distal colon, and their combined use resulted in a stronger inhibition than either compound alone [

42]. Notably, CBT’s inhibitory capacity was comparable to that of 5-ASA, aligning with previous findings on 5-ASA’s activity [

41]. Although the precise mechanism of their cooperative therapeutic action requires further clarification, the observed additive inhibition of PepT1 supports its involvement in their combined efficacy against colitis. In addition, these result may be clinically relevant, given that the presence of PepT1 mRNA and protein expression in the distal colonic epithelium of rats and humans and PepT1 protein upregulated in colonic epithelia of inflammatory bowel disease patients [

43].

Beyond its therapeutic benefit, CAA also offers a safety advantage by potentially minimizing systemic exposure to CBT. This was demonstrated by pharmacokinetic analysis, where plasma CBT concentrations were significantly lower following oral CAA administration than with direct CBT administration, with peak levels reduced by approximately half. The delayed systemic appearance of CBT (as shown in

Figure 6A) after oral CAA administration suggests that absorption primarily occurred in the colon, facilitated by the time required for CAA to transit to the lower intestine before drug release. Given the large intestine’s relatively low fluid content, reduced motility, and wider lumen—factors that impede efficient drug absorption—CBT liberated from CAA was absorbed to a lesser extent than orally administered CBT, which was primarily absorbed in the small intestine. Importantly, while CBT was still detectable in circulation after oral CAA administration, it did not induce the hypoglycemic effect observed with oral CBT administration at an equimolar dose, highlighting the attenuation in systemic effects via CSDD. These findings underscore CAA’s potential to mitigate adverse effects such as hypoglycemia and bone marrow toxicity [

33] upon drug repositioning of CBT to an anti-IBD drug.

Although the DNBS-induced colitis model is widely used to study intestinal inflammation, it has inherent limitations in recapitulating the complex pathophysiology of human inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) [

46]. DNBS-induced colitis primarily represents an acute, T cell-mediated immune response, whereas human IBD is characterized by a chronic and relapsing course involving multifactorial immune dysregulation, microbial interactions, and genetic susceptibility. Furthermore, the DNBS model lacks the genetic and environmental heterogeneity seen in patients and does not fully reproduce the epithelial barrier dysfunction and microbiome alterations that contribute to human disease progression [

47]. Therefore, our findings should be interpreted with caution, and extrapolation to clinical settings should be made carefully, acknowledging these translational limitations.

Historical reports have documented that high systemic doses of CBT may cause bone marrow suppression and kidney toxicity, raising concerns about its safety profile [

48]. In this study, our colon-targeted prodrug approach is designed to deliver CBT locally to the colon, which is expected to significantly reduce systemic exposure and consequently minimize these toxicities. Nevertheless, the potential for bone marrow and other systemic toxicities cannot be excluded, especially with long-term treatment. Therefore, future preclinical studies are essential to systematically evaluate these safety concerns.

In this study, we primarily focused on the functional inhibition of PepT1-mediated substrate transport rather than direct modulation of PepT1 protein expression in colonic tissue. While molecular or immunohistochemical analyses could provide additional mechanistic insights, to date, no small molecules have been reported to reduce PepT1 protein levels in normal colonic tissue. Future investigations incorporating molecular and immunohistochemical approaches will be essential to elucidate whether the tested compounds also influence PepT1 mRNA and protein expression in the colon.

In conclusion, CAA, produced by azo conjugation of CBT with salicylic acid, acts as a colon-specific mutual prodrug with superior efficacy to SSZ against rat colitis and reduces the risk of systemic side effects of CBT. Therefore, CAA may provide a promising therapeutic option for the treatment of IBD substituted for SSZ.