1. Introduction

The development of effective and precise drug delivery systems remains one of the most pressing challenges in modern medicine [

1]. Despite significant progress in pharmaceutical research, conventional drug delivery methods including systemic administration of small-molecule drugs, liposomes, polymeric nanoparticles, and micelles often face several limitations. These include poor solubility of drugs, rapid clearance from the bloodstream, lack of specificity toward target tissues, off-target effects, dose-limiting toxicities, and induction of immune responses. These obstacles are especially pronounced in the treatment of complex diseases such as cancer, chronic infections, and degenerative conditions, where therapeutic efficacy requires not only the delivery of active agents but also their sustained and controlled release at the site of action.

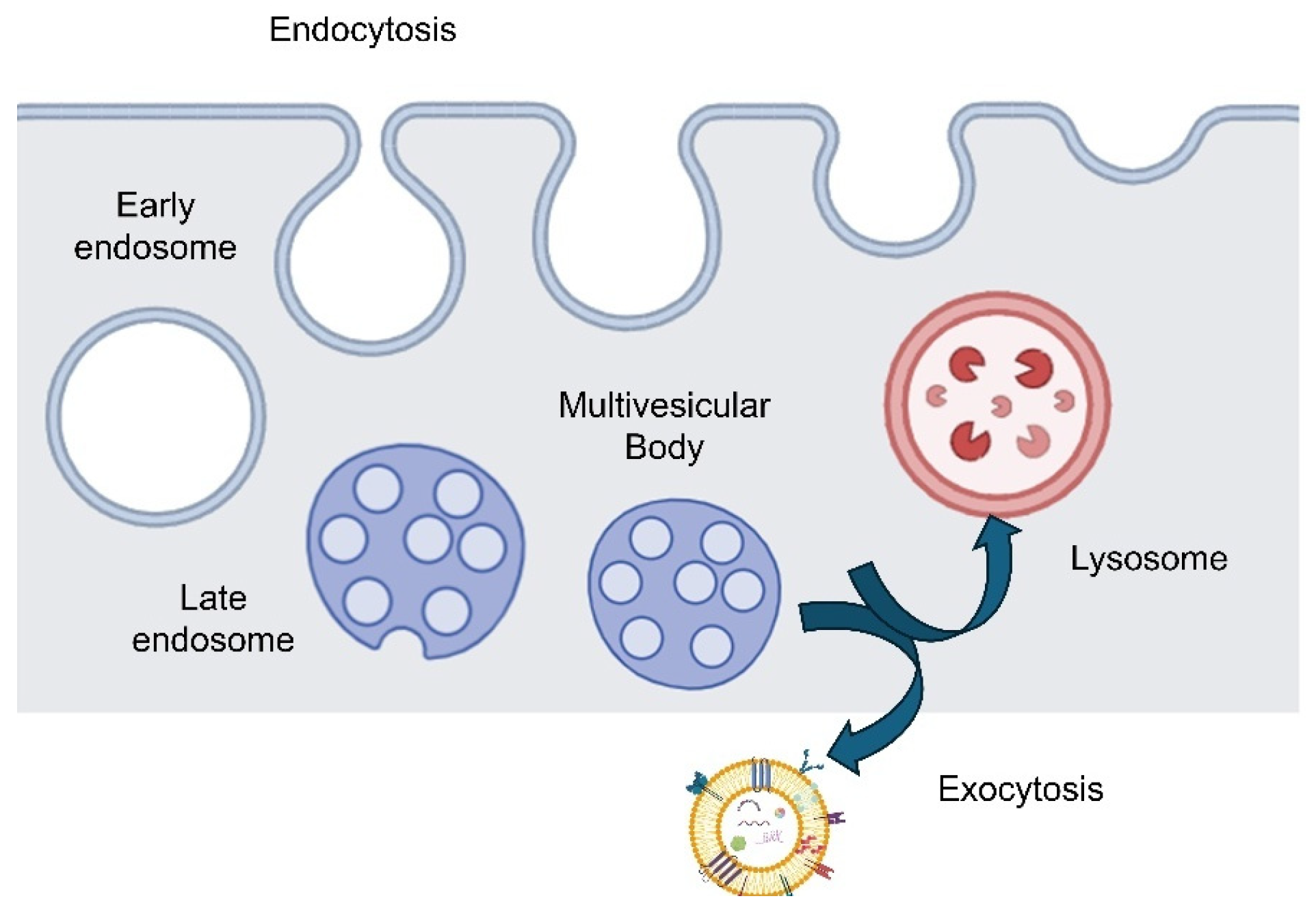

Over the past decade, exosomes have emerged as a highly promising platform for overcoming these limitations. Exosomes are a subtype of extracellular vesicles (EVs), typically ranging from 30 nm to 150 nm in diameter, and are naturally secreted by a wide variety of cell types. They originate from the inward budding of multivesicular bodies and are released into the extracellular space upon fusion with the plasma membrane. Exosomes carry a rich cargo of biologically active molecules, including proteins, lipids, RNAs (such as mRNAs and microRNAs), and metabolites, which they can transfer to recipient cells. Through this intercellular communication mechanism, exosomes play critical roles in regulating physiological and pathological processes, including immune responses, tissue regeneration, and disease progression [

2].

One of the most attractive features of exosomes as drug delivery vehicles lies in their natural origin and inherent biocompatibility [

3]. Being derived from the body’s own cells, exosomes are typically well-tolerated by the immune system, reducing the risk of immunogenicity often associated with synthetic delivery systems. In addition, exosomes possess intrinsic targeting capabilities, with surface proteins such as tetraspanins (CD9, CD63, CD81), integrins, and other adhesion molecules that can influence biodistribution and cell-specific uptake. These features provide a foundation for the development of personalized, cell-derived therapeutics with reduced systemic toxicity and improved pharmacokinetics [

4].

Moreover, exosomes can be engineered to enhance their therapeutic potential. Techniques such as electroporation, sonication, extrusion, and chemical conjugation can be employed to load exosomes with various therapeutic agents, including chemotherapeutic drugs, siRNA, miRNA, proteins, or CRISPR/Cas9 components. In parallel, surface modifications can be used to improve targeting or circulation time. Importantly, exosomes can also be produced from specific donor cells, such as mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs), immune cells, or cancer cells, each imparting unique biological properties that may enhance therapeutic effectiveness depending on the disease context [

5].

Given these capabilities, exosome-based drug delivery systems are gaining significant attention in three major biomedical domains: oncology, regenerative medicine, and infectious disease treatment. In cancer therapy, exosomes offer the ability to deliver cytotoxic agents or gene therapies directly to tumor sites, bypassing some of the resistance mechanisms associated with conventional therapies [

6]. In regenerative medicine, stem-cell-derived exosomes have shown potential in promoting tissue repair, angiogenesis, and anti-inflammatory responses, offering a cell-free alternative to stem cell transplantation [

7]. In the context of infectious diseases, exosomes may serve both as therapeutic agents by delivering antimicrobial drugs or immune modulators and as diagnostic biomarkers, given their ability to reflect the physiological status of their parent cells [

8].

Exosomes can be viewed not only as vesicular carriers but also through the lens of compartmentalization principles—in a similar conceptual space to biomolecular coacervates, liposomes, and phase-separated microdroplets. Like coacervates, exosomes feature selective partitioning of biomolecules: specific RNAs, proteins, or lipids are enriched inside relative to the surrounding cytosol or extracellular milieu. The mechanisms underlying this enrichment (e.g., affinity interactions, electrostatics, binding motifs, membrane microdomains) share conceptual parallels with driven phase separation in coacervate droplets. Moreover, exosomes exhibit responsive behavior (e.g., cargo release triggered by pH, redox, or enzyme cues) akin to stimuli-responsive coacervates. Exploring these analogies helps us think more broadly about cargo sorting, stability, and triggerable release in therapeutic exosome engineering [

9,

10].

Despite the promising outlook, the clinical translation of exosome-based therapies still faces several challenges. Standardization of isolation, purification, and characterization methods remains an ongoing issue, with various techniques yielding exosomes of different purity, size, and functionality [

11]. There is also a need for scalable and reproducible manufacturing processes that comply with regulatory standards for clinical-grade materials [

12]. Furthermore, questions remain about pharmacokinetics, biodistribution, and long-term safety of exosome-based therapeutics. Addressing these challenges will be essential to realizing the full potential of exosomes in clinical applications.

In this review, we aim to provide a comprehensive overview of the current state and prospects of exosome-based drug delivery systems, with a focus on their applications in cancer, regenerative medicine, and infectious diseases. Biogenesis, composition, and isolation methods of exosomes will be covered, followed by different strategies for drug loading and engineering. We then explore specific therapeutic applications in each of the three focal areas, highlighting preclinical and clinical findings, as well as the mechanisms by which exosomes exert their therapeutic effects. Finally, we discuss the translational hurdles that must be addressed and propose future directions for advancing the field.

3. Exosome Isolation and Characterization Techniques

Accurate and reproducible isolation and characterization of exosomes are critical for both fundamental research into intercellular communication and the development of exosome-based drug delivery systems. Exosomes, typically 30 nm–150 nm in diameter, exist in complex biological matrices co-present with other EV types, soluble proteins, lipoproteins, and nucleic acids making extraction nontrivial. Among standard approaches, ultracentrifugation (UC), whether as differential spin or density-gradient methods, remains widely employed. In differential UC, sequential low-speed centrifugations remove cells and debris, while high-speed spins at >100,000×

g pellet small EVs. Despite its landmark status, differential UC often yields moderate purity, with co-sedimentation of protein aggregates and lipoproteins, and can induce structural disruption via shear forces. Density-gradient UC, for example, using sucrose or iodixanol cushions offers higher purity by separating vesicles by buoyant density, yet at the cost of lower yield, extended ultracentrifugation times, and laborious layering steps. Both formats require specialist instrumentation, rigorous protocol standardization, and can suffer from limited reproducibility across labs [

34].

To overcome these challenges, size-exclusion chromatography (SEC) has gained traction as a gentle and reproducible alternative. In SEC, biofluids or concentrated samples are passed through columns packed with porous beads: larger particles such as exosomes elute in early fractions, while smaller proteins or aggregates are retained. Because SEC does not subject vesicles to high shear or osmotic pressure, it preserves structural and functional integrity. SEC yields higher purity than UC and maintains exosome bioactivity, while being both scalable and cost-effective no ultracentrifuge required making it attractive for clinical-grade exosome manufacturing (particularly when combined with upstream pre-concentration via ultrafiltration or tangential flow filtration) [

35].

Ultrafiltration (UF), which employs membrane filters with tuned pore sizes, serves primarily as a rapid means to concentrate large fluid volumes and remove debris. With membranes layered by molecular weight cutoff or pore size (~0.1 µm–0.2 µm), UF can reduce sample volumes efficiently. However, unmodified UF on its own does not separate contaminants from EVs effectively and may incur membrane clogging or shear-induced deformation of vesicles. As a result, UF is frequently used as a preparative step prior to SEC or other purification techniques. Notably, tangential flow filtration (TFF) in which flow tangentially sweeps contaminants off the membrane surface has emerged as superior to dead-end UF in minimizing fouling and improving recovery, especially in scalable workflows meant for therapeutic exosome production [

34].

Beyond physical separation, immunoaffinity-based isolation provides highly specific enrichment of exosome subtypes by targeting surface markers such as CD9, CD63, and CD81. Using antibody- or aptamer-functionalized magnetic beads or chromatography surfaces, this method can isolate defined exosome populations with exceptional purity ideal for biomarker discovery or functional studies. However, its output is typically low-yield and biased toward marker-positive subsets; costs per capture are high; and scaling to produce therapeutic quantities is limited. Thus, immunoaffinity is best suited for diagnostic or analytical applications rather than bulk drug delivery formulations [

34].

Microfluidics-based platforms often termed lab-on-chip devices have innovated exosome isolation via size-based filtration, affinity capture, acoustic or electric field manipulation (e.g., dielectrophoresis, acoustofluidics), and integrated detection. These devices can simultaneously isolate and characterize exosomes from minute sample volumes, often delivering high purity and rapid processing times (minutes rather than hours). Examples include herringbone micromixers coated with anti-CD63, nano-structured deterministic lateral displacement chips, and magneto-electrochemical sensors coupled with immunoaffinity capture. These systems offer promise for point-of-care diagnostics and small-volume studies. However, their throughput is currently limited, scaling is immature, and device fabrication remains expensive and non-standardized, though as microfabrication matures, clinical-grade microfluidic platforms may become more viable for integrated EV workflows [

36].

Increasingly, hybrid workflows combining multiple methods are favored. A common pipeline might begin with UF or TFF for concentration, followed by SEC for high purity, and optionally immunoaffinity capture for subtype-specific isolation. Such workflows can balance yield, purity, throughput, and functional preservation, and are consistent with the MISEV2018 guidelines, which recommend combining orthogonal separation modalities and testing for both positive (e.g., tetraspanins, TSG101, ALIX) and negative markers (e.g., nuclear or mitochondrial proteins) to assess contamination [

37].

When comparing methods holistically, ultracentrifugation offers moderate yield and purity but risks vesicle damage and poor reproducibility; SEC, especially when paired with UF or TFF, delivers high purity and scalability; immunoaffinity capture offers specificity but limits throughput; and microfluidic platforms enable rapid, automated isolation but are not yet optimized for large-volume workflows. Therefore, context-specific decisions are necessary: preclinical work may tolerate hybrid UC/SEC workflows, while therapeutic exosome production demands strict reproducibility and purity (best met via SEC + TFF pipelines). For diagnostic biomarker discovery, immunoaffinity and microfluidics may be especially valuable. A comparison of different isolation methods is depicted in

Table 3.

Physical loading methods such as electroporation and sonication can perturb exosomal membranes, with measurable consequences for how vesicles behave in vivo. Electroporation has repeatedly been shown to induce vesicle aggregation and alter basic surface properties, unless carefully buffered; these changes can impair the native ‘identity’ that guides biodistribution (e.g., increased size/aggregation and surface charge shifts that favor rapid uptake by the mononuclear phagocyte system) [

38]. Beyond general colloidal effects, specific surface proteins are causally linked to organ tropism in vivo: for example, swapping exosomal integrins re-routes uptake to lung vs. liver and redirects metastatic seeding in mice, demonstrating that altered surface-marker presentation can profoundly change biodistribution and biological outcomes [

39]. Protein corona remodeling can also retarget EVs in vivo—bound albumin was shown to steer EVs away from hepatic macrophages, further underscoring the sensitivity of biodistribution to surface chemistry [

40].

Consistent with these mechanisms, sonication and related membrane-perturbing workflows have been reported to disrupt exosomal membranes and/or membrane proteins, which multiple reviews note can translate into altered in vivo distribution and efficacy if not controlled [

41]. Mitigations exist: trehalose buffers reduce electroporation-induced aggregation, and optimized, low-stress electroporation protocols have achieved high drug loading and improved therapeutic responses without obvious loss of vesicle function, suggesting that careful parameterization can preserve integrity while gaining efficiency [

38]. Altogether, available in vivo and mechanistic evidence supports that changes to exosomal surface markers or membrane properties—whether from cargo-loading or corona formation—can significantly affect biodistribution and therapeutic effect, and thus should be characterized (size, zeta potential, surface proteins) and, where possible, stabilized by formulation [

42].

Following isolation, multi-modal characterization ensures exosome identity and quality (

Figure 3). Nanoparticle tracking analysis (NTA) estimates size distribution and particle concentration by tracking Brownian motion under laser illumination. NTA provides rapid quantitative insight, though results can be sensitive to instrument settings and may over- or under-estimate size due to subdiffusive motion artifacts; correction tools like Finite Track Length Adjustment (FTLA) have been proposed to improve accuracy [

43].

Transmission (TEM) and scanning electron microscopy (SEM) deliver nanoscale images of exosomes, confirming morphology (such as characteristic cup-shaped vesicles) and validating size. These techniques, however, are low throughput, time-intensive, and subject to sample preparation artifacts (e.g., dehydration, fixation). Thus TEM/SEM are best used to complement quantitative sizing data rather than serve as primary characterization tools.

Flow cytometry, especially specialized ‘nano-flow cytometry’ systems, enables surface marker profiling of exosomes at the single-vesicle level via fluorescent antibody labeling. Conventional cytometers struggle to resolve particles under ~200 nm and may suffer from “swarm detection” artifacts (multiple vesicles counted as one event). Nonetheless, where high-sensitivity instruments are available, flow cytometry can distinguish subpopulations by marker expression valuable in studying exosome heterogeneity across donor cell types or treatments [

44].

Western blotting, ELISA, or mass spectrometry-based proteomics enable molecular-level validation. Western blotting is commonly applied to detect canonical markers such as CD9, CD63, CD81, ALIX, TSG101, and HSP70/HSP90 and to verify absence of contaminating markers (e.g., nuclear or mitochondrial proteins). Such marker profiling aligns with MISEV guidelines and is essential for confirming vesicle identity and purity, though it is not quantitative in terms of particle count [

45].

Emerging techniques like tunable resistive pulse sensing (TRPS) measure size and zeta-potential via nanopore blockade, providing high-resolution size distribution and charge data. Super-resolution microscopy and Raman spectroscopy also enable single-vesicle-level molecular and structural profiling, though these remain primarily research tools at present [

45].

Ultimately, standardizing exosome isolation and characterization workflows is a key hurdle for translation. The lack of uniform reference materials, interlaboratory variability, and absence of established GMP-compliant protocols all pose barriers. Integrating methods that preserve bioactivity, quantify yield, ensure marker verification and scalability is essential to advance exosome-based drug delivery from bench to bedside.

4. Strategies for Drug Loading into Exosomes

The potential of exosomes as therapeutic delivery vehicles has garnered immense interest due to their inherent biocompatibility, stability in circulation, low immunogenicity, and natural ability to traverse biological barriers such as the blood–brain barrier (BBB) [

46]. A critical aspect of developing exosome-based drug delivery systems lies in efficiently loading therapeutic cargo ranging from small molecules and proteins to nucleic acids into exosomes. Broadly, drug loading strategies are categorized into endogenous (pre-secretory) and exogenous (post-secretory) methods. Each approach presents unique advantages and limitations in terms of efficiency, cargo stability, scalability, and translational applicability.

4.1. Endogenous Loading Strategies

Endogenous loading leverages the intrinsic cellular machinery to package therapeutic agents into exosomes during their biogenesis. This is typically achieved via either genetic engineering or passive incubation of donor cells with drugs.

One of the most precise and targeted approaches to loading exosomes is through the genetic engineering of parent cells, enabling selective incorporation of therapeutic molecules such as miRNAs, siRNAs, or therapeutic proteins. In this method, cells are transfected or transduced with plasmids encoding the desired therapeutic cargo, often fused with exosomal membrane proteins like CD63, Lamp2b, Alix, or TSG101, facilitating active sorting into exosomes [

47].

For example, Alvarez-Erviti et al. demonstrated that exosomes derived from dendritic cells expressing Lamp2b fused with a neuron-specific RVG peptide could deliver siRNA specifically to the brain in mice, resulting in gene knockdown [

48]. Similarly, Kojima et al. engineered exosomes to express synthetic RNA-binding domains, enabling programmable RNA loading through the EXOtic (EXOsomal transfer into cells) system [

49].

One of the main advantages of this approach is its highly specific and programmable cargo loading, allowing for precise delivery of desired molecules. It also ensures stable incorporation during exosome formation, which enhances the reliability of the delivery system. Additionally, it enables the incorporation of hard-to-load cargo such as proteins or large RNAs, expanding the range of therapeutic applications. However, there are notable limitations. The process is time-consuming and technically complex, which may hinder widespread adoption. There is also potential safety concerns associated with the use of viral vectors, raising regulatory and ethical considerations. Furthermore, the method faces challenges with scalability, limiting its feasibility for clinical translation.

An alternative endogenous approach involves passive incubation of donor cells with small-molecule drugs or nucleotides. These agents are internalized by cells and subsequently encapsulated into exosomes via natural sorting mechanisms. For instance, Pascucci et al. loaded paclitaxel into mesenchymal stromal cells (MSCs), which then secreted drug-loaded exosomes with potent anti-tumor effects [

50]. This approach is especially suitable for hydrophobic drugs that are easily internalized by cells and can integrate into exosomal membranes or lumens during exosome formation.

This method offers several advantages, including its simplicity and scalability, making it suitable for broader applications. It is non-invasive to the cellular machinery, minimizing potential disruption to cell function. Additionally, it avoids the use of complex vector systems, reducing technical challenges and safety concerns. However, it also presents some limitations. Loading efficiency is generally low and can be variable, which may affect consistency and effectiveness. There is also less control over cargo targeting or sorting, limiting precision in delivery. Moreover, there is a risk of drug degradation within the cells, which could compromise therapeutic outcomes.

4.2. Exogenous Loading Strategies

Exogenous or post-secretory loading involves manipulating isolated exosomes to encapsulate cargo after secretion. This strategy bypasses the complexities of cellular engineering and allows direct loading of purified exosomes.

Electroporation is one of the most widely used exogenous methods for loading nucleic acids into exosomes. By applying an electric field, transient pores are formed in the exosomal membrane, enabling cargo molecules particularly siRNAs or miRNAs to diffuse into the vesicle lumen. For instance, Wahlgren et al. successfully used electroporation to load siRNA into exosomes derived from human blood cells, demonstrating efficient delivery to recipient cells [

51]. However, electroporation has been reported to cause exosome aggregation or siRNA precipitation, potentially compromising vesicle integrity and reducing cargo bioavailability [

52].

This approach is particularly efficient for loading hydrophilic molecules such as RNA, making it valuable for nucleic acid-based therapies. It is also scalable and reproducible, supporting its potential for larger-scale applications. However, the method has several limitations. It may cause damage to exosomes or lead to their aggregation, which can affect their integrity and function. Loading efficiency can be inconsistent, posing challenges for standardization. Additionally, there is a risk of RNA degradation or precipitation during the process, which could reduce the effectiveness of the final therapeutic product.

Sonication uses ultrasonic waves to disrupt the exosomal membrane, allowing passive diffusion of cargo into the vesicles. This mechanical method has been shown to significantly enhance drug loading efficiency, especially for small hydrophobic molecules. Haney et al. demonstrated that macrophage-derived exosomes sonicated with catalase had improved drug encapsulation and therapeutic efficacy in a Parkinson’s disease model [

53].

This method offers high loading efficiency and is versatile, accommodating both hydrophilic and hydrophobic drugs, which broadens its therapeutic potential. However, it also presents important limitations. The process can cause structural damage to exosomes, potentially compromising their stability and function. It requires careful optimization to prevent degradation of the cargo, ensuring therapeutic efficacy. Additionally, the technique may alter surface markers or affect the biological activity of exosomes, which could impact targeting ability and safety profiles.

Perhaps the simplest method, incubation involves mixing exosomes with the drug under physiological or mildly acidic conditions, allowing spontaneous diffusion of cargo into the exosome membrane or lumen. This method is particularly effective for small hydrophobic drugs like curcumin or paclitaxel [

54]. For example, Sun et al. loaded curcumin into exosomes via passive incubation and reported enhanced anti-inflammatory activity in vitro [

55].

This method is non-invasive and easy to implement, making it an attractive option for exosome loading. It preserves the integrity of exosomes, which is crucial for maintaining their natural structure and function. Additionally, it is scalable and compatible with Good Manufacturing Practice (GMP) standards, supporting its potential for clinical translation. However, the method has limitations, including low loading efficiency, particularly for hydrophilic molecules. The loading process is largely uncontrolled, which may affect consistency and reliability. Furthermore, it is not well-suited for macromolecules like RNA, limiting its applicability for certain therapeutic cargos.

This technique involves subjecting exosomes and cargo to cycles of freezing and thawing, which transiently disrupts the exosomal membrane, facilitating cargo encapsulation. This method is commonly used in conjunction with proteins and peptides [

56]. This method is simple and does not require specialized equipment, making it accessible and easy to adopt in various settings. It is particularly suitable for loading peptides and proteins, offering a straightforward approach for incorporating biologically active molecules. However, it comes with several limitations. There is a risk of vesicle aggregation, which can affect the stability and function of the exosomes. Repeated loading cycles may lead to cargo leakage or degradation, reducing overall efficiency. Additionally, sensitive drugs are at risk of denaturation during the process, potentially compromising their therapeutic efficacy.

Each loading technique presents a trade-off between efficiency, vesicle integrity, cargo stability, and translational scalability. A comprehensive comparison is summarized in

Table 4:

Sonication and electroporation yield higher drug loading efficiency, but these methods may compromise the functional properties or surface markers of exosomes, affecting biodistribution and targeting. Conversely, endogenous methods, though labor-intensive, offer better control over cargo specificity and vesicle homogeneity. Furthermore, cargo type and intended therapeutic application often dictate the optimal loading strategy. For nucleic acid therapies targeting the central nervous system, electroporation combined with targeting ligand modification may be preferable. In contrast, hydrophobic small-molecule drugs can be effectively loaded via simple incubation methods without compromising exosomal integrity (

Figure 4).

The choice of strategy is highly dependent on the nature of the therapeutic agent, desired targeting, and clinical application. A growing trend toward hybrid loading approaches combining endogenous and exogenous techniques is emerging to maximize efficiency and therapeutic efficacy. Moreover, advances in microfluidics, synthetic biology, and membrane engineering are expected to further refine loading technologies, enhancing the scalability, reproducibility, and clinical translatability of exosome-based drug delivery systems. Future research should also prioritize standardization of quantitative metrics for loading efficiency, stability assays, and in vivo functional validation to ensure consistent and safe clinical outcomes.

7. Advantages of Exosome-Based Systems

One of the key strengths of exosomes as drug delivery vehicles lies in their endogenous origin they are naturally secreted by cells and composed of native lipids, proteins, and nucleic acids, which make them inherently biocompatible and minimally immunogenic (

Table 7). Unlike synthetic nanoparticles or viral vectors, exosomes avoid provoking adverse immune reactions, even upon repeat administration [

97]. This low immunogenicity enables safer and more prolonged systemic exposure, reducing the risk of clearance and anti-carrier immune responses. Indeed, exosome-based delivery systems have demonstrated significantly reduced toxicity and immune activation, offering a safer profile particularly important for chronic or repeated treatments in fields like oncology and neurology [

98].

Exosomes possess natural targeting capabilities derived from surface proteins and lipids that reflect their cell of origin. These molecular signatures—such as tetraspanins, integrins, and other adhesion molecules—can mediate specific interactions with recipient cells or tissues, enabling homing without the need for external modifications [

99]. Such intrinsic targeting supports both passive and active delivery. Passive targeting occurs through biodistribution and physiological tropism, particularly in tumors or inflamed tissues. Active targeting can arise from exosomes sourced from specific cells; for example, exosomes derived from brain-homing cells may preferentially deliver cargo to the central nervous system. Exosome delivery can occur across barriers such as the blood–brain barrier (BBB), which is notoriously difficult for other carriers to penetrate. This natural tropism reduces off-target effects and enhances delivery precision, making exosomes attractive for therapeutic areas like neurodegeneration, oncology, and organ-specific regenerative medicine [

99].

A vital advantage of exosome carriers is their lipid bilayer encapsulation, which shields sensitive therapeutic cargo such as RNA, protein, or small molecules from degradation by enzymes, pH changes, or serum nucleases in circulation [

98]. Compared to free cargo or cargo encapsulated within synthetic nanoparticles, exosome-loaded molecules retain structural integrity and bioactivity for longer durations. This encapsulation also helps promote endosomal escape and efficient functional delivery to the cytoplasm of recipient cells [

67]. Furthermore, exosomes exhibit longer circulation half-lives relative to many synthetic nanocarriers. This extended presence in the bloodstream enhances the probability of reaching target tissues, increases dosing flexibility, and reduces the frequency of administration required for therapeutic efficacy [

65].

Exosomes can carry a broad spectrum of therapeutic agents, including nucleic acids (mRNA, miRNA, siRNA), proteins, peptides, and small molecules. This versatility allows exosome platforms to accommodate complex biologics and gene therapies that often suffer from poor delivery efficiency in traditional systems [

100]. For example, exosome carriers are being engineered for delivery of CRISPR-Cas RNPs, enabling genome editing in neurological disease models, something conventional vectors struggle to achieve with precision and reduced immunogenicity [

67].

One of the most notable features of exosomes is their ability to penetrate physiological barriers, particularly the BBB. This property allows delivery of therapeutic agents to the brain via systemic administration, unlocking opportunities in neurodegenerative disorders such as Alzheimer’s, Huntington’s, and Parkinson’s diseases. Additionally, exosomes have demonstrated efficient tissue permeation in models of tumor targeting, organ regeneration, and cardiovascular repair. This capability arises from their small size (30 nm–150 nm), natural trafficking routes, and interactions with target cell receptors [

101].

Advances in bioengineering and surface engineering have enabled the development of engineered exosomes with tuned tropism, modified surface ligands, pH-sensitive release motifs, or magnetic guidance yet still preserving the biocompatible and low-immunogenic core [

67].

Moreover, several groups are improving manufacturing processes to support scalable, reproducible GMP-grade production of exosomes with controlled cargo loading and batch consistency. Combined with advances in microfluidic isolation, ultrafiltration, and size-exclusion techniques, these manufacturing innovations strengthen the industrial viability of exosome platforms [

102].

8. Limitations and Challenges

Although exosome-based drug delivery systems offer promising advantages, their translation into clinical use remains impeded by significant technical, production, and regulatory hurdles. The key challenges include low isolation yield and purity, lack of standardized production protocols, limited loading efficiency and reproducibility, regulatory and scalability issues, and the potential for immunological effects depending on the exosome source (

Table 8).

A fundamental barrier facing exosome research is the inherently low yield and inconsistent purity of exosome preparations. Typical isolation from cell culture media yields less than 1 µg of exosome protein per mL of conditioned medium, whereas therapeutic dosing in preclinical animal studies often requires tens to hundreds of micrograms per subject [

103]. Common isolation techniques—such as ultracentrifugation, ultrafiltration, size-exclusion chromatography, or polymer precipitation—frequently co-isolate contaminants including protein aggregates, lipoproteins, and cellular debris, compromising exosome purity and downstream functionality [

103]. These limitations impose high input requirements, increase cost, and limit scalability for therapeutic applications.

The fragmentation of methodologies across exosome studies undermines comparability and reproducibility. There is no universally accepted protocol for critical steps such as cell source selection, culture conditions, isolation, quantification, or quality control—resulting in high variability in exosome composition and bioactivity between labs and batches [

104]. Such heterogeneity impedes establishment of reliable potency assays and comparability across preclinical and clinical studies. Recognizing this, professional bodies like the International Society for Extracellular Vesicles (ISEV) and others have called for standardized reporting of key experimental parameters and adherence to minimal information guidelines [

105].

Efficient and consistent cargo loading remains a major technical challenge. Passive techniques like simple incubation tend to result in low encapsulation rates (often <10%), highly influenced by the physicochemical properties of the cargo and limited by non-specific associations rather than true luminal loading [

65]. More active methods like electroporation, sonication, detergent permeabilization, and freeze/thaw can improve cargo load but introduce issues such as RNA degradation, vesicle aggregation, vesicle damage, or inconsistent loading across batches [

105]. For example, electroporation may result in RNA aggregation and particle aggregation, reducing actual loading below 0.05% in some cases [

104]. Reproducibility remains low in part because standardized metrics and experimental details such as EV-to-cargo ratios, temperature/time profiles, or post-loading purification are often incompletely reported [

105].

Clinical translation requires reliable large-scale GMP production systems with rigorous control of quality, potency, and safety. However, scaling current laboratory-based workflows to manufacturing scale is challenging due to low yield, heterogeneous product, and the absence of robust potency or batch-release assays [

106]. Regulatory bodies—such as the FDA, EMA, and national agencies—have yet to establish specific guidelines tailored for exosome-based products, meaning developers must align with broader cell therapy and biologics frameworks. This creates ambiguity regarding classification (as biologics, ATMPs, or drug delivery systems), as well as for required testing—including characterization of identity, purity, potency, biodistribution, pharmacokinetics, dose-finding, immunogenicity, and tumorigenicity [

107]. Without standardized safety/efficacy endpoints, translation is slowed by inconsistent regulatory expectations across jurisdiction.

While exosomes are often lauded for low immunogenicity, immune responses may still arise depending on the cell source or purification quality. Serum-derived or MSC-derived exosomes can carry immunomodulatory molecules (MHC proteins, cytokines, small RNAs) that may trigger unintended immune activation or tolerance. Moreover, contaminating proteins or residual cell components can act as immunogens if not removed thoroughly [

103]. Additionally, differences in biodistribution and clearance such as uptake by the reticuloendothelial system (RES) are influenced by membrane composition and zeta-potential, potentially triggering rapid clearance or inflammatory responses [

65]. Without full profiling of exosome surface proteins and cargo, immune safety remains an open question.

Another understudied yet critical challenge is stability—many formulations of exosomes are stored at ultra-low temperatures (e.g., −80 °C), which is impractical for commercial or clinical deployment. Publication-level data on shelf-life, formulation stability, or stability under typical shipping and handling conditions is largely lacking. Such gaps pose hurdles for translation into off-the-shelf products and influence decisions around lyophilization, cryopreservation, or buffer formulation [

65].

Among these challenges, the most significant current barrier is manufacturing scale-up and standardization for clinical-grade production. Conventional isolation methods such as ultracentrifugation or polymer precipitation typically yield heterogeneous vesicle populations of limited purity, which undermines batch-to-batch reproducibility and complicates compliance with Good Manufacturing Practice (GMP) requirements. Without robust scalable technologies (e.g., bioreactor-based production, tangential-flow filtration, microfluidics), achieving consistent therapeutic doses is not feasible for late-phase clinical trials. Closely linked to this are regulatory acceptance hurdles, since agencies such as FDA and EMA require clear criteria for product identity, potency, and release testing—standards that are difficult to establish without reliable large-scale production platforms. In contrast, targeting specificity, although an important determinant of therapeutic efficacy, is advancing rapidly through surface engineering strategies, ligand display, and exosome–nanoparticle hybrids. Therefore, while all three remain relevant, the primary bottleneck for translation is manufacturing and regulatory readiness, with targeting specificity considered a more tractable technical challenge under active development [

108].

To improve the clinical viability of exosome therapeutics, several strategies are emerging (

Figure 5):

Enhanced production platforms: Utilization of bioreactors (e.g., stirred-tank, hollow-fiber, suspension systems) and optimized cell culture media enhances exosome yield while improving batch consistency [

98].

Standardized protocols and reporting: Adoption of ISEV-recommended guidelines for minimal data reporting and methodology will help improve experimental rigor and cross-study comparability [

105].

Hybrid and engineered exosomes: Membrane-hybrid approaches that combine synthetic liposomes and natural EVs may improve cargo loading and stability while preserving targeting capability [

65].

Optimized active loading strategies: Refinements in electroporation parameters, microfluidic loading, or novel permeabilization tools may increase reproducibility while limiting cargo degradation or vesicle damage [

105].

Regulatory engagement: Early and sustained dialogue with regulatory agencies to co-develop guidance on product classification, potency assays, and acceptable quality attributes will foster translational progress [

107].

Figure 5.

Limitations of Exosome Therapeutics and Strategies to Overcome Them. Schematic summary of the key limitations of exosome-based drug delivery—including low yield, heterogeneous populations, rapid clearance, and limited targeting specificity—and strategies under investigation to address these challenges. Solutions depicted include scalable bioreactor production, advanced purification methods, surface engineering for improved tropism, and hybrid exosome–nanoparticle systems.

Figure 5.

Limitations of Exosome Therapeutics and Strategies to Overcome Them. Schematic summary of the key limitations of exosome-based drug delivery—including low yield, heterogeneous populations, rapid clearance, and limited targeting specificity—and strategies under investigation to address these challenges. Solutions depicted include scalable bioreactor production, advanced purification methods, surface engineering for improved tropism, and hybrid exosome–nanoparticle systems.

While exosome-based systems deliver compelling advantages in drug delivery, their translation is limited by multiple challenges including low and impure yields, inconsistent production protocols, weak cargo-loading reproducibility, unclear regulatory pathways, potential immunogenicity, and poor stability. Addressing these limitations through technological innovation, standardized practices, and regulatory alignment is essential. As the field matures, coordinated efforts across academia, industry, and regulatory stakeholders will be key to unlocking the full therapeutic potential of exosome-based therapeutics.

9. Market for Exosomes and Regulatory Challenges

A growing number of biotechnology companies are advancing exosome-based therapeutics and establishing scalable manufacturing platforms for clinical use (

Table 9). Aegle Therapeutics (Miami, FL, USA) is a regenerative medicine company advancing extracellular vesicle (EV) therapies to address rare and debilitating dermatological diseases, notably Recessive Dystrophic Epidermolysis Bullosa (RDEB). Their lead candidate, AGLE-102, a composite of EVs including exosomes derived from bone marrow–mesenchymal stem cells (BM-MSCs), is currently in a Phase 1/2 clinical trial for RDEB. These EVs, isolated using Aegle’s proprietary harvesting technology, serve as key bioactive agents of MSCs, delivering proteins and nucleic acids (such as microRNAs and mRNAs) that influence tissue regeneration through paracrine signaling. This signaling enhances cell proliferation, migration, and survival, both locally and systemically. Notably, BM-MSC EVs are capable of transferring essential skin basement membrane proteins like collagen IV and VII, which are directly relevant to the pathology of RDEB. With MSCs known for their ability to differentiate into various mesodermal tissues, Aegle’s approach harnesses their regenerative potential through the targeted use of secreted EVs, offering a novel therapeutic avenue for cutaneous repair and broader systemic applications [

109].

Capricor Therapeutics (San Diego, CA, USA) is advancing a multi-stage pipeline centered on allogeneic cardiosphere-derived cells (CDCs) and exosome-based therapies to address a wide range of serious diseases. Their lead candidate, deramiocel (CAP-1002), consists of CDCs stromal cells derived from healthy human heart tissue originally discovered by Capricor’s scientific founder, Dr. Eduardo Marbán, at Johns Hopkins University. CDCs have been extensively studied, featured in over 100 peer-reviewed publications, and administered in multiple clinical trials involving more than 200 patients. In the context of Duchenne muscular dystrophy (DMD), deramiocel exerts immunomodulatory, anti-inflammatory, pro-angiogenic, and anti-fibrotic effects, largely mediated through exosomes containing bioactive molecules such as microRNAs. These exosomal contents modulate immune responses, particularly by altering gene expression in macrophages, thereby reducing inflammation and promoting tissue regeneration. Capricor’s ongoing research also focuses on characterizing and expanding deramiocel’s potential, including its use in combination with other emerging DMD therapies to address the broader pathophysiology of this chronic inflammatory condition [

110].

Evox Therapeutics (Oxford, UK) is pioneering the use of engineered exosomes to safely and effectively deliver genome-editing tools for the treatment of neurological and neurodegenerative diseases. Their approach combines the precision of CRISPR-Cas genome editing with the natural delivery capabilities and safety profile of exosomes, overcoming limitations associated with traditional CNS-targeting methods like viral vectors or lipid nanoparticles. Evox’s exosome-based platform enables targeted, transient delivery of Cas ribonucleoproteins, minimizing off-target effects, reducing immunogenicity, and allowing for safe re-dosing. These exosomes exhibit broad tissue tropism and effective neuronal penetration, making them ideal for CNS applications. Evox is developing therapies for diseases with well-defined genetic drivers, including Spinocerebellar Ataxia type 2 (SCA2) via ATXN2 targeting, and Huntington’s disease through MSH3 suppression, with potential relevance to other repeat expansion disorders. Their modular exosome platform supports diverse genome-editing technologies and is being expanded through strategic partnerships, aiming to unlock treatment options for a broad range of severe genetic conditions beyond the CNS [

111].

Aruna Bio’s (Athens, GA, USA) lead therapeutic exosome, AB126, is uniquely engineered for central nervous system (CNS) specificity; its surface carries neural-derived receptors and proteins, enabling it to cross the blood–brain barrier and naturally home to brain regions such as the cerebellum and basal ganglia. In preclinical studies, AB126 exhibits innate therapeutic activity without additional payloads: it reduces neuroinflammation, protects neurons, and promotes neuroregeneration, including enhanced stem-cell proliferation and remyelination. Moreover, AB126 engages an anti-inflammatory mechanism via degradation of extracellular ATP into adenosine mediated by its intrinsic CD39/CD73 enzymatic markers supporting modulation of the immune cascade in both acute and chronic CNS disease models. The FDA has cleared its IND for a Phase 1b/2a clinical trial in acute ischemic stroke, making AB126 the first exosome therapy to enter human trials for a neurological indication; enrollment is planned in patients with poor prognosis following thrombectomy. Aruna also piloted AB126 in preclinical ALS (SOD1) mouse models, where it extended survival, reduced inflammation, and lowered neurofilament light chain biomarkers after weekly dosing. Complementing its therapeutic profile, Aruna has developed a scalable cGMP manufacturing platform with proprietary expertise in exosome purification, concentration, and batch consistency, enabling production of clinical-grade material and eventual scale-up through Phase 3 and potential commercialization [

112].

EverZom (Paris, France), founded in 2019 by researchers from CNRS and Université Paris Cité, is a pioneering biotech developer of exosome-based regenerative therapies, recognized as a winner of the prestigious European EIC Accelerator Program. Its mission is to become a leader in therapeutically leveraging exosomes across diverse clinical contexts. The company has built a comprehensive, patent-protected innovation platform covering the entire exosome value chain from cell sourcing and exosome generation to cargo loading and formulation. This platform is optimized for high-yield, scalable and reproducible manufacturing, including mechanical stimulation methods that boost exosome output by orders of magnitude and facilitate clinical-grade production. EverZom’s lead product, EVerGel, targets digestive tissue healing, specifically Crohn’s-related perianal fistulas and post-surgical anastomotic healing. The therapeutic combines stem cell-derived exosomes with a thermosensitive hydrogel to enable controlled, localized release. Preclinical studies across multiple animal models have shown rapid healing, reduced inflammation, and minimized fibrosis. IND-enabling studies are expected by late 2024, with first-in-human dosing anticipated in early 2026. A second candidate, administered intravenously, is designed to promote organ regeneration, beginning with treatment of liver failure in chronic insufficiency settings such as cirrhosis. EverZom’s platform has already validated the manufacture of its first GMP-grade exosome batch at scale in a 10 L bioreactor, developed in partnership with the French Blood Establishment (EFS), achieving unprecedented yields and paving the way to clinical translation by early 2025 [

113].

Aposcience AG (Vienna, Austria) is a leading innovator in regenerative medicine, developing therapies based on the secretome, a potent, cell-free mixture of bioactive molecules secreted by apoptotic peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs). Unlike exosome-only therapies, which isolate a specific extracellular vesicle subtype, secretome-based therapies encompass a broader range of biologically active components including proteins, lipids, cytokines, growth factors, and exosomes, offering multi-modal regenerative effects. This comprehensive approach is designed to restore tissue function rather than merely repair damage. Aposcience’s core platform uses PBMCs that are driven into apoptosis through controlled stress (e.g., irradiation), triggering the release of a highly active secretome. This secretome has shown superior efficacy in promoting wound healing, skin regeneration, and recovery from ischemic inflammatory conditions such as myocardial infarction, stroke, and spinal cord injury. Two formulations are under development: APO-1 (systemic) and APO-2 (topical), both produced from the secretome of healthy donor blood using a proprietary process. These formulations enhance healing by stimulating keratinocyte and fibroblast migration, improving angiogenesis, and increasing oxygen and nutrient delivery to damaged tissue. The company’s flagship clinical program, APO-1, is currently being evaluated in the MARSYAS II multinational, randomized, double-blind clinical trial for the treatment of acute myocardial infarction (MI). In preclinical models, APO-1 significantly reduced infarct size and preserved heart function, both with and without reperfusion, demonstrating its potential to prevent adverse cardiac remodeling in over 700,000 patients globally who undergo reperfusion therapy annually. If successful, APO-1 could address a market opportunity of € 1–2 billion per year [

114].

Codiak BioSciences (Cmabridge, MA, USA) was a recognized leader in this space [

115]. Codiak’s exoASO-C/EBPβ was a novel therapeutic that selectively targets the transcription factor C/EBPβ in immunosuppressive myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSCs), leading to immune modulation and potent systemic anti-tumor activity across multiple MDSC-rich, checkpoint-resistant tumor models. By leveraging exosome surface glycoproteins, the therapy enables precise uptake of antisense oligonucleotide (ASO) payloads by MDSCs and monocytes, facilitating effective delivery to distant, extra-hepatic tumor sites. This targeted delivery results in modulation of the tumor microenvironment and activation of T-cell-mediated anti-tumor responses, which are further enhanced when combined with anti-PD1 checkpoint inhibitors. Preclinical studies demonstrated robust monotherapy efficacy across several administration routes, underscoring the platform’s potential applicability in various cancers. Transcriptomic analyses using data from The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) further identified C/EBPβ and MDSC-related gene signatures enriched across diverse tumor types, supporting broad clinical relevance. In parallel, exoASO-STAT6, another candidate from Codiak’s exoASO™ platform, targets STAT6 in tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs), particularly within hepatic tumors such as hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC). Systemic administration in preclinical models resulted in durable, dose-dependent liver retention of the ASO and sustained downregulation of STAT6 mRNA, along with modulation of downstream immune pathways. STAT6 and IL-4 receptor (IL4R) expression in human HCC TAMs, along with the identification of a STAT6-related transcriptional signature associated with poor prognosis in HCC and other cancers, supports the rationale for clinical development [

116]. However, the financial risk of exosome-based companies is high. For example, Codiak Biosciences filed for bankruptcy in 2023.

In the manufacturing domain, several companies are building GMP-compliant infrastructure to support clinical and commercial needs. EXO Biologics (Lieja, Belgium), headquartered in Liège, Belgium, is a leader in developing therapeutics based on mesenchymal stromal cell-derived exosomes. Its proprietary ExoPulse™ platform supports GMP-compliant production, purification, and characterization of exosomes for clinical use [

117]. The company’s subsidiary CDMO, ExoXpert, was launched to meet growing global demand for clinical-grade exosomes. ExoXpert operates a state-of-the-art GMP facility utilizing ExoPulse™, offering full-scale production capacity for both internal projects and external partners. Their lead therapeutic candidate, EXOB-001, is an MSC-derived exosome formulation currently in an EMA-approved Phase I/II clinical trial (EVENEW) for the prevention of bronchopulmonary dysplasia (BPD) in preterm infants. This program represents the first European Medicines Agency-authorized exosome-based therapy in clinical development [

118]. Additional milestones include grant of Orphan Drug Designation and Rare Pediatric Disease Designation by both EMA and FDA for EXOB-001, and ExoXpert receiving GMP certification from the Belgian medicines agency, enabling the first specialized exosome CDMO in Europe and demonstrating capability to reliably produce GMP-grade exosomes, including loading of mRNA and DNA payloads with up to ~80% retention, paving the path for exosome-based gene delivery applications [

119].

Kimera Labs (Miramar, FL, USA) is a biotechnology company specializing in exosome-based innovations, with a strong commercial focus on topical skin health and cosmetic applications. Their flagship product, Vive, represents the culmination of years of exosome research, formulated specifically to support skin vitality, hydration, and youthful appearance. Vive contains 2 trillion microvesicles per 5 mL vial, including billions of biologically active exosomes, derived from mesenchymal stem cells. These exosomes act as cellular messengers, promoting intercellular communication that may support skin texture, elasticity, and regeneration. The formula also combines amino acids (the building blocks of proteins), hyaluronic acid (for deep hydration), and trehalose (for cellular protection and moisture retention), making it a multifunctional skin therapy [

120]. Unlike pharmaceutical exosome platforms still in clinical development, Vive is already commercially available and widely used as a topical cosmetic product, often in conjunction with aesthetic procedures such as microneedling, laser resurfacing, or RF therapy. This positions Kimera Labs at the intersection of regenerative science and luxury skincare, offering consumers access to non-invasive, cell-derived regenerative treatments that tap into the biological power of exosomes for visible skin rejuvenation.

ExoCoBio’s (Geumcheon-gu, Seoul) Derma Signal SRLV (marketed as ASCE+ SRLV) is a next-generation topical skin regeneration treatment that leverages the therapeutic power of exosomes, nano-sized extracellular vesicles involved in cellular communication and repair. Utilizing ExoCoBio’s proprietary ExoSCRT™ purification technology, the exosomes in Derma Signal SRLV are highly purified and bioactive, enabling them to modulate skin repair processes at the cellular level. Clinical and preclinical data suggest impressive regenerative effects, including up to a 690% increase in collagen production, a 300% boost in elastin, and a 75% reduction in melanin, contributing to visibly firmer, brighter, and more even-toned skin. The treatment is particularly effective for deep skin rejuvenation, accelerated healing after cosmetic procedures (such as laser, microneedling, or chemical peels), and hydration enhancement, while also offering benefits for sensitive or inflamed skin conditions such as rosacea or acne. It helps reduce pigmentation, improve skin texture, and minimize scarring by promoting keratinocyte and fibroblast activity. Administered typically via microneedling, the recommended protocol involves a minimum of three sessions spaced 3–4 weeks apart, targeting the face, neck, and décolleté. Already in commercial use in aesthetic clinics, Derma Signal SRLV exemplifies how exosome science is being effectively translated into high-performance cosmetic dermatology [

121].

RION (Rochester, MN, USA), founded in 2017 through the Mayo Clinic Employee Entrepreneurial Program and headquartered in Rochester, MN, is a clinical-stage regenerative medicine company pioneering a novel exosome therapeutic platform. Its core innovation, Purified Exosome Product™ (PEP™), is a shelf-stable lyophilized powder derived from human platelets and discovered within the Mayo Clinic’s Van Cleve Cardiac Regenerative Medicine Program [

122]. PEP™ exosomes are engineered to accelerate tissue repair by promoting cell proliferation, angiogenesis, and inflammation resolution while stabilizing cellular microenvironment integrity. Leveraging a proprietary biomanufacturing platform, RION has scaled PEP™ production to clinical and commercial standards, supported by over 30 peer-reviewed publications and multiple IND-enabling preclinical programs across wound healing, musculoskeletal, cardiovascular, pulmonary, and women’s health indications. Clinically, PEP™ is advancing through human trials: a Phase 2A study in Diabetic Foot Ulcers (DFUs) commenced dosing in May 2024, enrolling 59 patients and focusing on safety and healing efficacy versus standard care. A separate Phase 1b trial launched in early 2025 evaluates intra-articular injection of PEP™ for knee osteoarthritis, with enrollment initiated in March 2025 across multiple U.S. centers. RION’s platform exemplifies how platelet-derived exosomes can transform regenerative medicine through off-the-shelf, clinically scalable solutions that empower the body’s innate healing mechanisms [

122].

In addition to product developers, contract manufacturing organizations like SCTbio (Praha, Czech Republic) and Lonza (Basilea, Switzerland) are providing essential GMP production and testing services to support exosome therapeutics at scale [

123,

124]. RoosterBio (Frederick, MD, USA), in collaboration with Thermo Fisher Scientific (Waltham, MA, USA), offers engineered MSC platforms and bioprocess tools to streamline exosome manufacturing workflows for clinical-grade applications [

125].

Collectively, these companies are laying the foundation for the clinical and commercial translation of exosome-based therapies, addressing key challenges in scalability, reproducibility, and regulatory compliance while expanding therapeutic possibilities across oncology, regenerative medicine, infection and rare diseases.

Table 9.

Leading companies in the manufacturing of exosomes.

Table 9.

Leading companies in the manufacturing of exosomes.

| Company | Focus Area | Lead Candidate | Modality | Development Stage | Ref |

|---|

| Aegle Therapeutics | Dermatology (RDEB) | AGLE-102 | BM-MSC-derived EVs | Phase 1/2 Clinical Trial | [109] |

| Capricor Therapeutics | Muscular dystrophy, Inflammation | Deramiocel (CAP-1002) | Cardiosphere-Derived Cells (CDCs) and Exosomes | Clinical Trials (DMD, others) | [110] |

| Evox Therapeutics | Neurological diseases (e.g., SCA2, HD) | Genome-editing exosome platform | Engineered Exosomes + CRISPR-Cas RNPs | Preclinical/Strategic partnerships | [111] |

| Aruna Bio | CNS (e.g., Stroke, ALS) | AB126 | Neural Exosomes with BBB penetration | Phase 1b/2a Clinical Trial | [112] |

| EverZom | Digestive healing, Organ regeneration | EVerGel | Stem cell-derived Exosomes + Hydrogel | Preclinical; IND-enabling by 2024 | [113] |

| Aposcience AG | Cardiovascular, Skin regeneration | APO-1, APO-2 | PBMC-derived Secretome (incl. Exosomes) | Phase 2 (MI), Preclinical | [114] |

| Codiak BioSciences | Oncology (Checkpoint-resistant tumors) | exoASO-C/EBPβ, exoASO-STAT6 | Engineered Exosomes + ASOs | Preclinical (Bankruptcy in 2023) | [116] |

| EXO Biologics/ExoXpert | Neonatal lung disease (BPD) | EXOB 001 | MSC-derived Exosomes | Phase 1/2 Clinical Trial (EMA-approved) | [119] |

| Kimera Labs | Cosmetics, Skin health | Vive | Topical MSC-derived Exosomes | Commercial (Cosmetic Use) | [120] |

| ExoCoBio | Aesthetic Dermatology | Derma Signal SRLV (ASCE+) | Topical Exosomes (ExoSCRT™ tech) | Commercial (Aesthetic Clinics) | [121] |

| RION | Regenerative medicine | PEP™ | Platelet-derived Exosomes (Lyophilized) | Phase 2A (DFU), Phase 1b (OA) | [122] |

| RoosterBio/Thermo Fisher | GMP Manufacturing Tools | MSC + Bioprocess Platforms | Clinical-grade MSC-derived Exosomes | Manufacturing Support | [125] |

| SCTbio, Lonza | Contract Manufacturing | Not applicable | CDMO Services for Exosomes | GMP-compliant manufacturing | [123,124] |

In addition to the well-established oncology and regenerative medicine programs already discussed, several emerging or exploratory clinical studies illustrate the widening therapeutic scope of exosome-based interventions. Trials such as NCT02310451 investigated the role of exosomes in melanoma pathogenesis, underscoring their diagnostic and mechanistic relevance in cancer biology. Other studies have explored regenerative and anti-inflammatory applications, including NCT04270006 (adipose-derived stem cell exosomes for periodontitis) and NCT06853522 (human umbilical cord MSC-derived exosomes for active ulcerative colitis). Novel neuromodulatory approaches have also been initiated, such as NCT04202783, assessing exosomes for craniofacial neuralgia, and a recent project combining focused ultrasound with exosome delivery for depression, anxiety, and dementias. Cosmetic and dermatologic uses are beginning to emerge, exemplified by NCT06932393, a not-yet-recruiting trial evaluating exosomes for hair loss treatment [

126].

Although many of these trials remain early-stage or exploratory, collectively they demonstrate the diversification of exosome therapeutics beyond classical indications, expanding toward inflammatory, neurological, metabolic, and aesthetic domains. This expansion highlights both the translational promise and the ongoing regulatory and methodological challenges associated with defining optimal sources, dosing, and endpoints for exosome-based therapies.

The clinical translation of exosome-based therapies faces substantial regulatory challenges arising from their complex biological nature, heterogeneous manufacturing processes, and lack of tailored guidance. The regulatory landscape for exosome-based therapeutics is still evolving, reflecting the novelty and heterogeneity of these biological nanocarriers. Both the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and the European Medicines Agency (EMA) currently classify exosome therapeutics under existing frameworks for biological products or advanced therapy medicinal products (ATMPs), depending on their origin, manipulation level, and intended use [

127]. In the United States, the FDA’s Center for Biologics Evaluation and Research (CBER), through the Office of Tissues and Advanced Therapies (OTAT), oversees clinical development of extracellular vesicle (EV)-based products, treating them similarly to human cell- and tissue-based products (HCT/Ps) that require comprehensive demonstration of safety, identity, purity, potency, and consistency under Good Manufacturing Practice (GMP) conditions. In Europe, most exosome candidates fall within the ATMP category, necessitating compliance with the EMA’s guidelines on Investigational Medicinal Products (IMPs) and centralized authorization for commercialization [

128]. Up to date, no exosome-based therapy has yet achieved approval from the FDA or EMA; in the U.S., exosome products are classified as 351 biologics and must meet rigorous standards akin to those for other biologic drugs [

108]. The absence of specific, globally harmonized regulatory guidelines means developers often rely on frameworks for cell and tissue products as proxies, leading to inconsistencies and ambiguity across jurisdictions [

129]. Regulatory agencies consistently emphasize the need for standardized analytical characterization to define exosome identity and potency. The International Society for Extracellular Vesicles (ISEV) and the International Society for Cell & Gene Therapy (ISCT) have issued consensus guidelines (MISEV2018) describing essential physicochemical and molecular markers—including tetraspanins (CD9, CD63, CD81), TSG101, and Alix—as well as recommended assays for particle quantification, sterility, and residual nucleic acids [

130]. Despite these advances, no harmonized potency assays or release criteria yet exist, representing a critical gap for both the FDA and EMA. Current efforts focus on establishing fit-for-purpose regulatory standards that align exosome product quality testing with biologics and cell-therapy benchmarks, while ensuring scalability and reproducibility of manufacturing under GMP.

In contrast, exosomes have already reached the commercial market in cosmetics and dermatology, where regulatory requirements are lighter. Companies such as BENEV (Mission Viejo, CA, USA) Company Inc., Kimera Labs (Miramar, FL, USA), and RION (Rochester, MN, USA) Aesthetics sell topical exosome-containing serums, skin rejuvenation solutions, and post-procedure products for aesthetic use. These exosomes are often derived from mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) and marketed as cosmeceutical products that claim to enhance skin appearance without therapeutic claims, thereby avoiding the strict clinical standards required for drug approval. Although widely used in medical spas and aesthetic clinics, such products are not FDA-approved drugs, and their safety and efficacy claims are largely unverified in peer-reviewed clinical trials [

120,

131,

132].

Overall, the convergence of regulatory initiatives and academic standardization efforts is gradually shaping a coherent framework for exosome-based therapeutics, but ambiguities remain in classification, potency evaluation, and long-term safety assessment. Addressing these issues will be essential to enable consistent regulatory approval and clinical adoption of exosome-derived medicines worldwide.

10. Future Directions and Emerging Trends

Exosome-based technologies have reached a pivotal point, with several therapeutic programs progressing through clinical trials. However, to fully unlock their translational potential, the field is rapidly evolving along several key technological and scientific axes. These emerging directions aim to overcome current challenges related to reproducibility, targeting, therapeutic efficacy, and scalability while expanding the scope of applications.

To address issues of low yield and scalability, exosome-mimetic nanoparticles—artificial vesicles designed to mimic the biological composition, size, and functional properties of natural exosomes—are under investigation. These can be created via top-down approaches such as cell extrusion, or bottom-up assembly using synthetic lipids and engineered proteins. Exosome-mimetics offer advantages such as higher production yields, easier functionalization, and tunable pharmacokinetics compared to naturally derived exosomes. Several platforms are now producing hybrid vesicles that combine biological membranes with synthetic carriers, integrating exosomal targeting capabilities with the controlled payload delivery of liposomes or polymeric nanoparticles [

133].

Exosomes are being actively engineered as precision delivery systems for complex biologics. Recent advances have demonstrated successful exosomal delivery of CRISPR-Cas9 ribonucleoproteins, mRNA constructs, and siRNAs targeting disease-driving genes in neurodegenerative and oncologic contexts. This approach not only enhances delivery specificity but also reduces the immunogenicity and off-target risks associated with viral or synthetic carriers. Engineered exosomes carrying immune checkpoint inhibitors, tumor-associated antigens, or tolerogenic peptides are also being explored to modulate immune responses in cancer, autoimmune diseases, and transplantation [

134].

Examples include the exoASO™ platform from Codiak BioSciences, which targets transcriptional regulators like STAT6 in tumor-associated macrophages [

116], and Evox Therapeutics’ genome-editing exosomes, developed for disorders like Spinocerebellar Ataxia 2 and Huntington’s disease [

111]. These innovations point toward a future where exosomes serve not just as delivery vehicles, but as highly programmable, multifunctional nanomedicines.

Artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning are increasingly being leveraged to optimize exosome development pipelines. From predicting optimal cell sources and culture conditions to identifying key surface markers for targeting, AI offers powerful tools to accelerate discovery and standardize exosome production. For instance, algorithms can be trained on high-dimensional omics data (proteomics, lipidomics, transcriptomics) to classify exosome subtypes with superior therapeutic potential or design synthetic ligands that enhance targeting efficiency [

135,

136]. AI is also emerging in image-based tracking and biodistribution studies, enabling non-invasive evaluation of exosome uptake, clearance, and interaction with specific tissues. As more datasets from clinical and preclinical studies become available, the role of AI in exosome drug development is expected to expand substantially, particularly in personalized medicine contexts.

Cell source heterogeneity remains a bottleneck for reproducible exosome production. To address this, current trends favor the use of clonally engineered cell lines, such as human embryonic kidney (HEK293) cells or immortalized mesenchymal stem cells, engineered for stable exosome output, surface marker consistency, and reduced immunogenicity. Some platforms now incorporate genetic circuits to modulate exosome biogenesis, control secretion rates, or direct loading of specific cargo into the intraluminal space [

137].

In parallel, stem cell-derived exosomes, particularly those from mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs), continue to be a preferred source due to their inherent anti-inflammatory and regenerative properties. Companies like EXO Biologics and Aruna Bio are advancing cGMP-compatible production systems based on MSC and neural stem cell lines, respectively, aiming for consistency in clinical-grade batches [

112,

119]. These efforts are expected to support standardized, scalable, and regulatory-compliant manufacturing processes across various therapeutic indications.

Another innovative trend is the integration of exosomes with stimuli-responsive delivery systems that enable spatiotemporal control of therapeutic release. These hybrid systems incorporate environmental triggers such as pH, temperature, enzymatic activity, redox gradients, or ultrasound to selectively release exosomal cargo in diseased tissues. For instance, tumor microenvironments often exhibit acidic pH or elevated matrix metalloproteinases, which can be used to trigger drug release from modified exosomes only within the tumor site, thereby enhancing therapeutic index and reducing systemic toxicity [

138].

Additionally, exosome–hydrogel composites are being developed for localized, sustained release, particularly in regenerative medicine and wound healing. Thermo-sensitive gels, loaded with exosomes, allow for site-specific application and prolonged therapeutic activity. EverZom’s EVerGel platform exemplifies this trend, combining MSC-derived exosomes with hydrogel matrices for tissue repair in Crohn’s-related perianal fistulas [

113].

Together, these emerging trends highlight a rapidly maturing field that is actively addressing its early limitations through interdisciplinary innovation. The future of exosome-based therapeutics lies not just in natural vesicles, but in rationally designed, multifunctional, and customizable delivery systems capable of addressing complex diseases. Continued integration of bioengineering, synthetic biology, and computational design, along with rigorous regulatory frameworks, will be essential for unlocking the full clinical impact of exosome science.

As novel formulations enter clinical pipelines and next-generation platforms become commercially viable, exosome systems are poised to become a cornerstone of precision nanomedicine, bridging the gap between biologics, gene therapy, and personalized drug delivery.