Drug-Integrating Amphiphilic Nano-Assemblies: 3. PEG-PPS/Palmitate Nanomicelles for Sustained and Localized Delivery of Dexamethasone in Cell and Tissue Transplantations

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

2.2. Synthesis of Polymeric Amphiphilic Diblock Copolymers

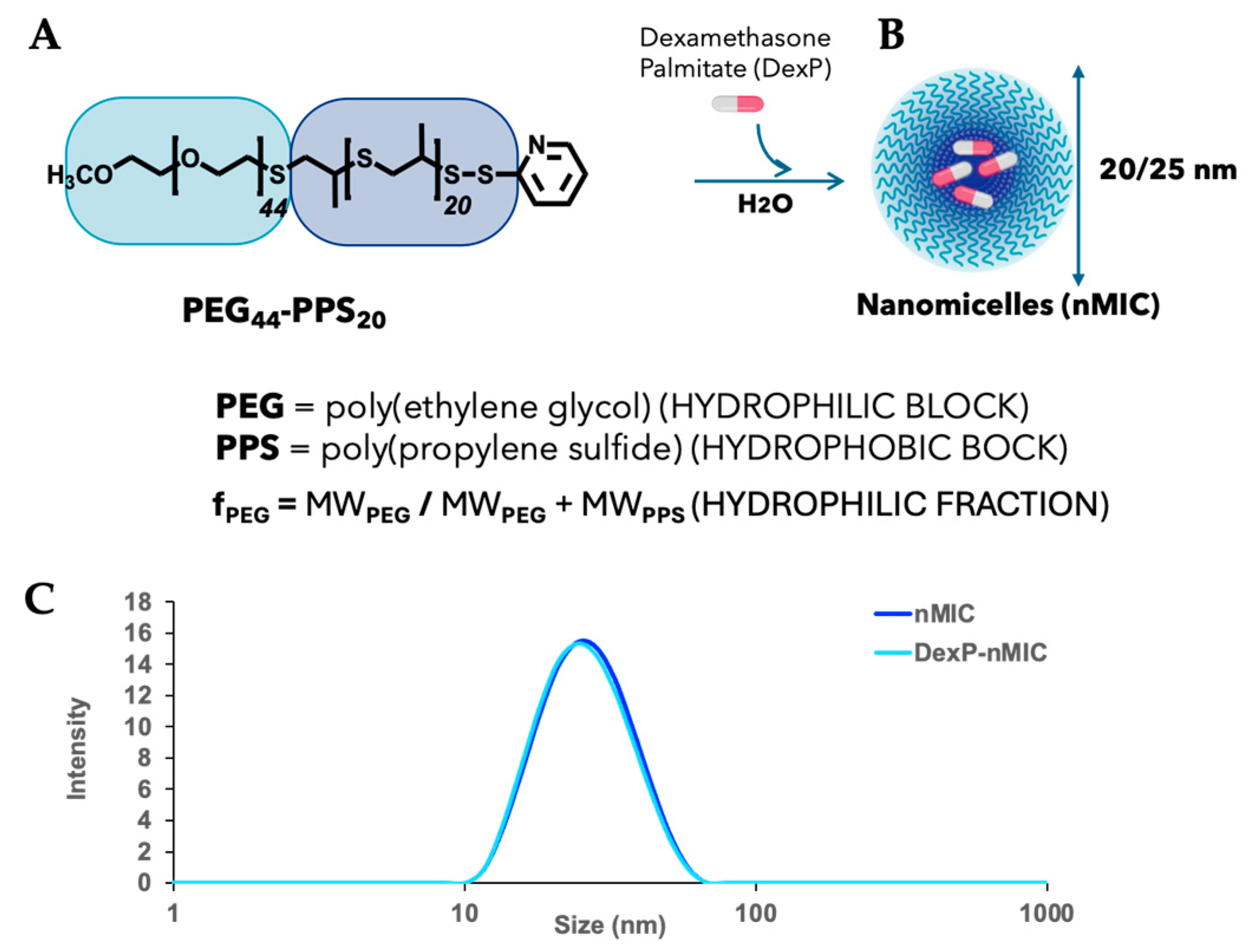

2.3. Preparation and Characterization of Drug-Integrating Amphiphilic Nanomaterial Assemblies (DIANAs)

2.4. Nanomicelle Drug-Loading Efficiency

2.5. Preparation of Fluorescently Labeled nMIC

2.6. Drug Release Study

2.7. Inhibition of Interleukin-6 Secretion from Mouse Macrophages In Vitro

2.8. Inhibition of NF-kB Secretion from Human Monocytes In Vitro

2.9. Perifusion Studies with Human Islets

2.10. Animal Work

2.10.1. Pharmacokinetic Study in Mice and Rats

2.10.2. Mouse Allogenic Skin Transplant Model

3. Results and Discussion

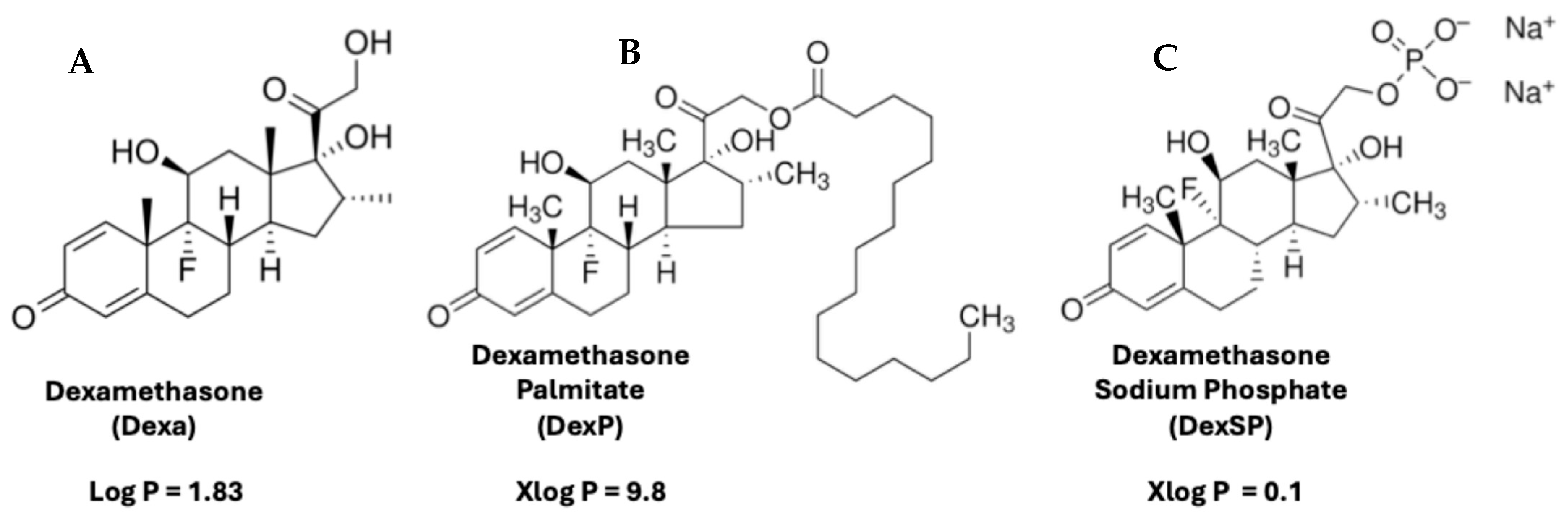

3.1. Synthesis and Self-Assembling of PEG44–PPS20 Block Copolymers

3.2. Drug Release

3.3. Inhibition of Interleukin-6 Secretion In Vitro Using Mouse Macrophages

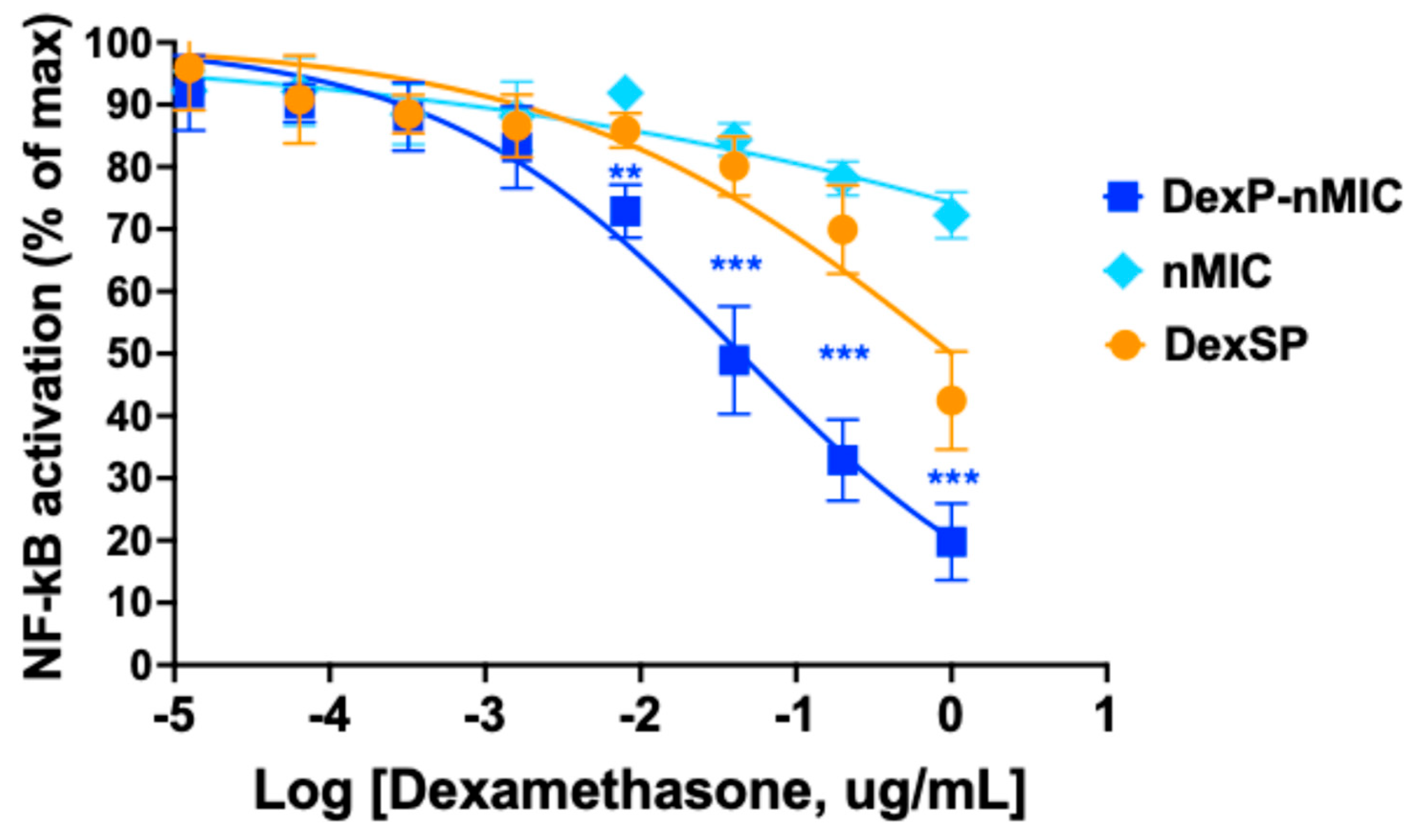

3.4. Inhibition of the NF-κB Pathway in Human Monocytes

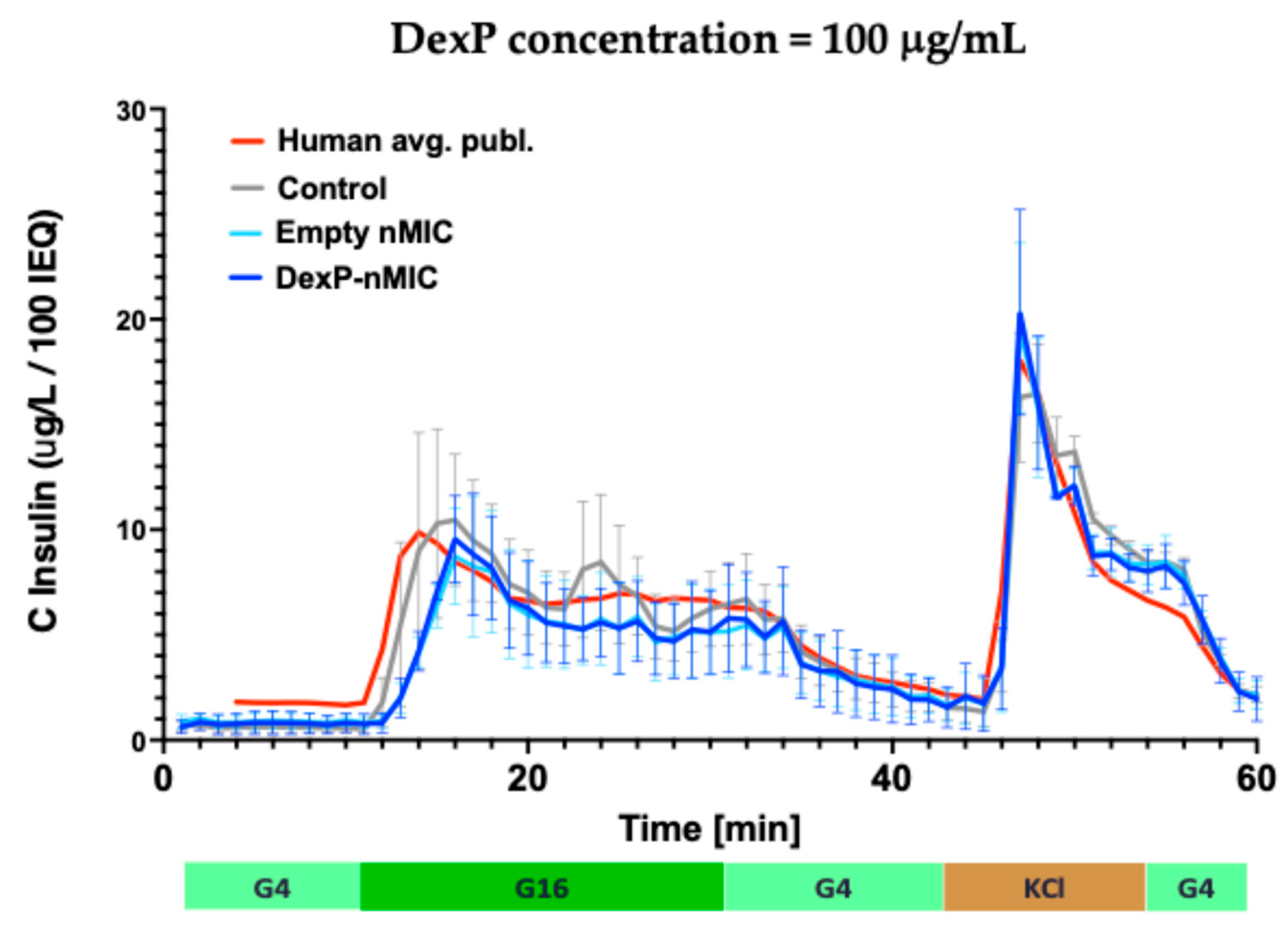

3.5. Effect on GSIS in Human Islets

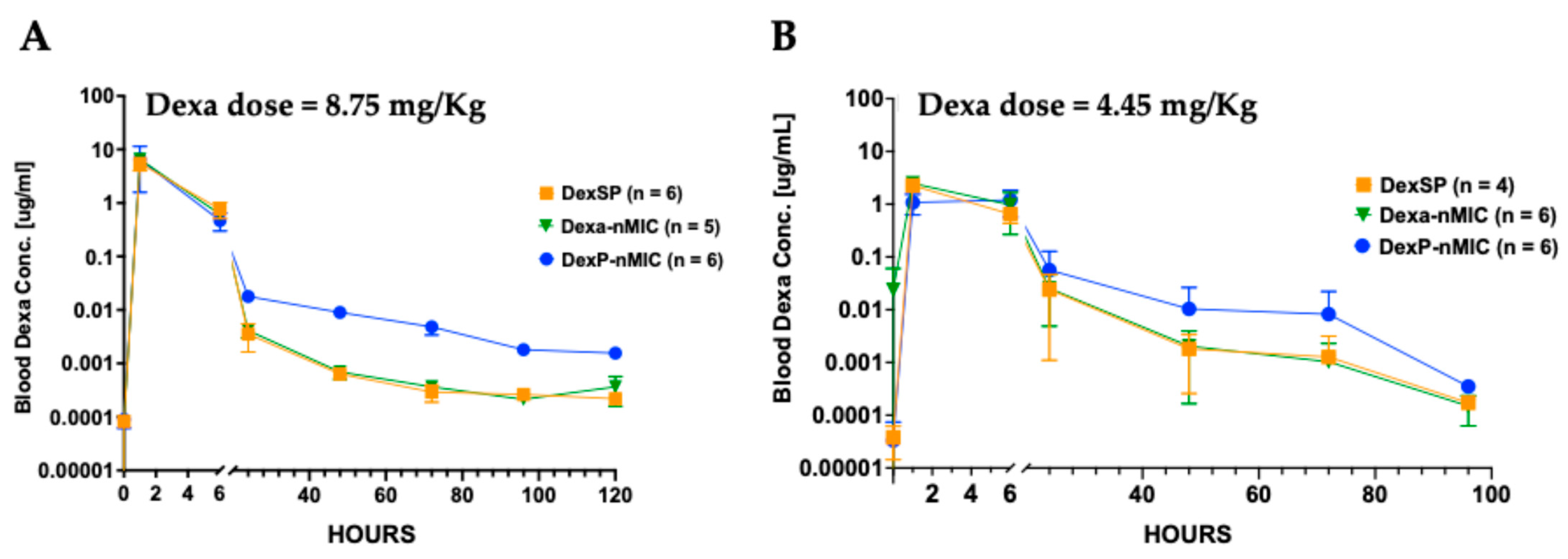

3.6. Pharmacokinetic (PK) Study in Mice and Rats

3.7. Allogeneic Mouse Skin Transplant Model

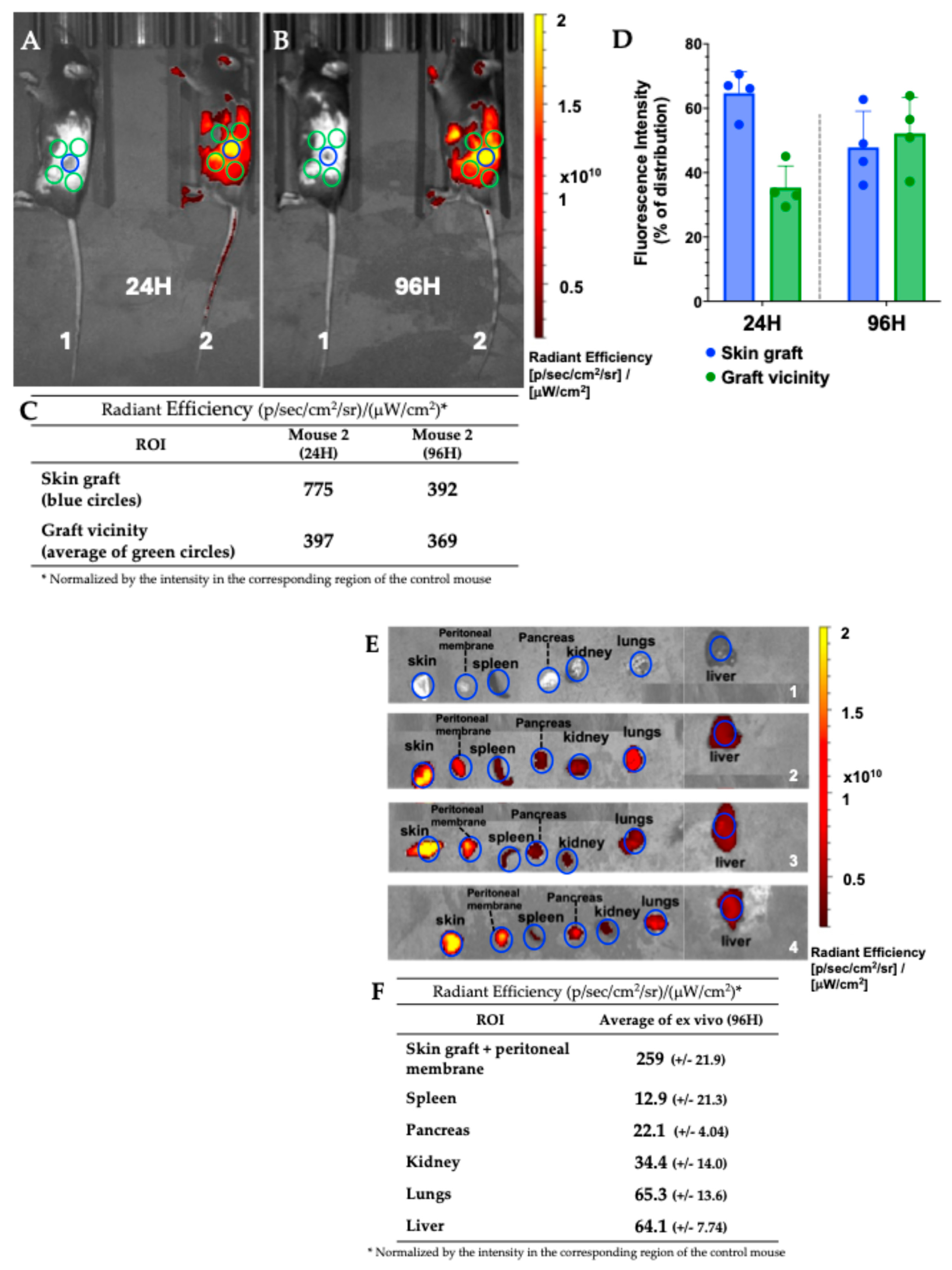

3.7.1. Mouse Skin Transplant Live Imaging

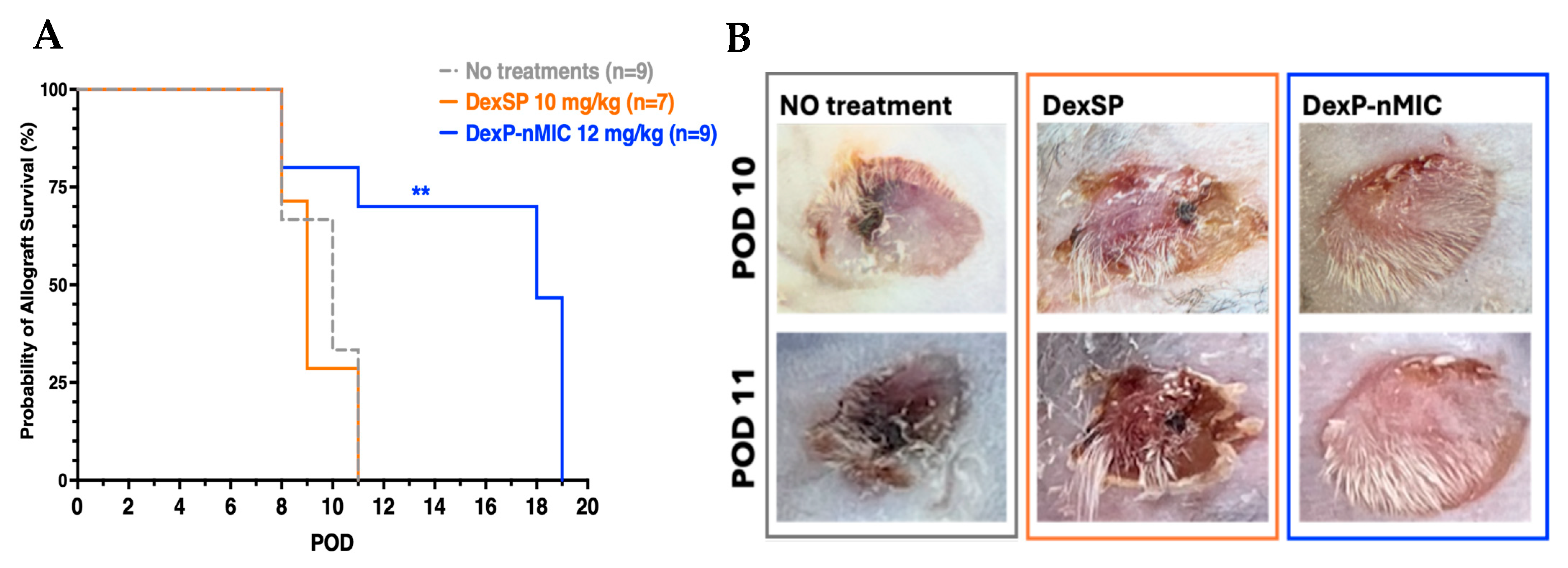

3.7.2. Allogeneic Mouse Skin Transplant Survival

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| 1H NMR | Proton nuclear magnetic resonance |

| CoSE | Cosolvent evaporation |

| Dexa | Dexamethasone |

| DexP | Dexamethasone palmitate |

| DexSP | Dexamethasone sodium phosphate |

| DIANAs | Drug-Integrating Amphiphilic Nano-Assemblies |

| DLS | Dynamic light scattering |

| IVIS | In Vivo Imaging System |

| LISAI | Local Immune Suppression and Anti-inflammatory |

| MeOH | Methanol |

| nMICs | Nanomicelles |

| PEG | Poly(ethylene glycol) |

| PK | Pharmacokinetic |

| POD | Post-operation day |

| PPS | Poly(propylene sulfide) |

| RP-HPLC | Reverse-phase high-performance liquid chromatography |

| T1D | Type 1 Diabetes |

References

- Rech Tondin, A.; Lanzoni, G. Islet cell replacement and regeneration for type 1 diabetes: Current developments and future prospects. BioDrugs 2025, 39, 261–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liblau, R.S.; Wong, F.S.; Mars, L.T.; Santamaria, P. Autoreactive CD8 T cells in organ-specific autoimmunity: Emerging targets for therapeutic intervention. Immunity 2002, 17, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, P.J.; Pipella, J.; Rutter, G.A.; Gaisano, H.Y.; Santamaria, P. Islet autoimmunity in human type 1 diabetes: Initiation and progression from the perspective of the beta cell. Diabetologia 2023, 66, 1971–1982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quattrin, T.; Mastrandrea, L.D.; Walker, L.S.K. Type 1 diabetes. Lancet 2023, 401, 2149–2162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bloomgarden, Z.T. Diabetes complications. Diabetes Care 2004, 27, 1506–1514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gregg, E.W.; Li, Y.; Wang, J.; Burrows, N.R.; Ali, M.K.; Rolka, D.; Williams, D.E.; Geiss, L. Changes in diabetes-related complications in the United States, 1990–2010. N. Engl. J. Med. 2014, 370, 1514–1523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathis, D.; Vence, L.; Benoist, C. β-Cell death during progression to diabetes. Nature 2001, 414, 792–798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lablanche, S.; Vantyghem, M.C.; Kessler, L.; Wojtusciszyn, A.; Borot, S.; Thivolet, C.; Girerd, S.; Bosco, D.; Bosson, J.L.; Colin, C.; et al. Islet transplantation versus insulin therapy in patients with type 1 diabetes with severe hypoglycaemia or poorly controlled glycaemia after kidney transplantation (TRIMECO): A multicentre, randomised controlled trial. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2018, 6, 527–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markmann, J.F.; Rickels, M.R.; Eggerman, T.L.; Bridges, N.D.; Lafontant, D.E.; Qidwai, J.; Foster, E.; Clarke, W.R.; Kamoun, M.; Alejandro, R.; et al. Phase 3 trial of human islet-after-kidney transplantation in type 1 diabetes. Am. J. Transplant. 2021, 21, 1477–1492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shapiro, A.M.; Pokrywczynska, M.; Ricordi, C. Clinical pancreatic islet transplantation. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 2017, 13, 268–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lacy, P.E.; Kostianovsky, M. Method for the isolation of intact islets of Langerhans from the rat pancreas. Diabetes 1967, 16, 35–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruni, A.; Gala-Lopez, B.; Pepper, A.R.; Abualhassan, N.S.; Shapiro, A.J. Islet cell transplantation for the treatment of type 1 diabetes: Recent advances and future challenges. Diabetes Metab. Syndr. Obes. 2014, 7, 211–223. [Google Scholar]

- Ricordi, C.; Lacy, P.E.; Finke, E.H.; Olack, B.J.; Scharp, D.W. Automated method for isolation of human pancreatic islets. Diabetes 1988, 37, 413–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stabler, C.L.; Russ, H.A. Regulatory approval of islet transplantation for treatment of type 1 diabetes: Implications and what is on the horizon. Mol. Ther. 2023, 31, 3107–3108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, S.M.; Kim, K.W. Is islet transplantation a realistic approach to curing diabetes? Korean J. Intern. Med. 2017, 32, 62–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hering, B.J.; Clarke, W.R.; Bridges, N.D.; Eggerman, T.L.; Alejandro, R.; Bellin, M.D.; Chaloner, K.; Czarniecki, C.W.; Goldstein, J.S.; Hunsicker, L.G.; et al. Phase 3 trial of transplantation of human islets in type 1 diabetes complicated by severe hypoglycemia. Diabetes Care 2016, 39, 1230–1240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, B.X.; Teo, A.K.K.; Ng, N.H.J. Innovations in bio-engineering and cell-based approaches to address immunological challenges in islet transplantation. Front. Immunol. 2024, 15, 1375177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Q.; Huang, Y.X.; Liu, L.; Zhao, X.H.; Sun, Y.; Mao, X.; Li, S.W. Pancreatic islet transplantation: Current advances and challenges. Front. Immunol. 2024, 15, 1391504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- The Lancet Diabetes and Endocrinology. Stem-cell therapy for diabetes: The hope continues. Lancet Diab. Endocrinol. 2024, 12, 775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czarnecka, Z.; Dadheech, N.; Razavy, H.; Pawlick, R.; Shapiro, A.M.J. The current status of allogenic islet cell transplantation. Cells 2023, 12, 2423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grattoni, A.; Korbutt, G.; Tomei, A.A.; Garcia, A.J.; Pepper, A.R.; Stabler, C.; Brehm, M.; Papas, K.; Citro, A.; Shirwan, H.; et al. Harnessing cellular therapeutics for type 1 diabetes mellitus: Progress, challenges, and the road ahead. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 2025, 21, 14–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barton, F.B.; Rickels, M.R.; Alejandro, R.; Hering, B.J.; Wease, S.; Naziruddin, B.; Oberholzer, J.; Odorico, J.S.; Garfinkel, M.R.; Levy, M.; et al. Improvement in outcomes of clinical islet transplantation: 1999–2010. Diabetes Care 2012, 35, 1436–1445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernandez-Fisac, I.; Pizarro-Delgado, J.; Calle, C.; Marques, M.; Sanchez, A.; Barrientos, A.; Tamarit-Rodriguez, J. Tacrolimus-induced diabetes in rats courses with suppressed insulin gene expression in pancreatic islets. Am. J. Transplant. 2007, 7, 2455–2462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marzorati, S.; Bocca, N.; Molano, R.D.; Hogan, A.R.; Doni, M.; Cobianchi, L.; Inverardi, L.; Ricordi, C.; Pileggi, A. Effects of systemic immunosuppression on islet engraftment and function into a subcutaneous biocompatible device. (Abstr.). Transplant. Proc. 2009, 41, 352–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruhlmann, A.; Nordheim, A. Effects of the immunosuppressive drugs CsA and FK506 on intracellular signalling and gene regulation. Immunobiology 1997, 198, 192–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abraham, R.T.; Wiederrecht, G.J. Immunopharmacology of rapamycin. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 1996, 14, 483–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gruppuso, P.A.; Boylan, J.M.; Sanders, J.A. The physiology and pathophysiology of rapamycin resistance: Implications for cancer. Cell Cycle 2011, 10, 1050–1058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silva, I.B.B.; Kimura, C.H.; Colantoni, V.P.; Sogayar, M.C. Stem cells differentiation into insulin-producing cells (IPCs): Recent advances and current challenges. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 2022, 13, 309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maffi, P.; Bertuzzi, F.; De Taddeo, F.; Magistretti, P.; Nano, R.; Fiorina, P.; Caumo, A.; Pozzi, P.; Socci, C.; Venturini, M.; et al. Kidney function after islet transplant alone in type 1 diabetes: Impact of immunosuppressive therapy on progression of diabetic nephropathy. Diabetes Care 2007, 30, 1150–1155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Velluto, D.; Bojadzic, D.; De Toni, T.; Buchwald, P.; Tomei, A.A. Drug-integrating amphiphilic nanomaterial assemblies: 1. Spatiotemporal control of cyclosporine delivery and activity using nanomicelles and nanofibrils. J. Control. Release 2021, 329, 955–970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lansberry, T.R.; Stabler, C.L. Immunoprotection of cellular transplants for autoimmune type 1 diabetes through local drug delivery. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2024, 206, 115179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiggins, S.C.; Abuid, N.J.; Gattas-Asfura, K.M.; Kar, S.; Stabler, C.L. Nanotechnology approaches to modulate Immune responses to cell-based therapies for type 1 diabetes. J. Diabetes Sci. Technol. 2020, 14, 212–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plumblee, L.; Atkinson, C.; Jaishankar, D.; Scott, E.; Tietjen, G.T.; Nadig, S.N. Nanotherapeutics in transplantation: How do we get to clinical implementation? Am. J. Transplant. 2022, 22, 1293–1298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brubaker, C.E.; Velluto, D.; Demurtas, D.; Phelps, E.A.; Hubbell, J.A. Crystalline oligo(ethylene sulfide) domains define highly stable supramolecular block copolymer assemblies. ACS Nano 2015, 9, 6872–6881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cerritelli, S.; Velluto, D.; Hubbell, J.A. PEG-SS-PPS: Reduction-sensitive disulfide block copolymer vesicles for intracellular drug delivery. Biomacromolecules 2007, 8, 1966–1972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Toni, T.; Dal Buono, T.; Li, C.M.; Gonzalez, G.C.; Chuang, S.T.; Buchwald, P.; Tomei, A.A.; Velluto, D. Drug integrating amphiphilic nano-assemblies: 2. Spatiotemporal distribution within inflammation sites. Pharmaceutics 2024, 16, 652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Velluto, D.; Demurtas, D.; Hubbell, J.A. PEG-b-PPS diblock copolymer aggregates for hydrophobic drug solubilization and release: Cyclosporin A as an example. Mol. Pharm. 2008, 5, 632–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Velluto, D.; Thomas, S.N.; Simeoni, E.; Swartz, M.A.; Hubbell, J.A. PEG-b-PPS-b-PEI micelles and PEG-b-PPS/PEG-b-PPS-b-PEI mixed micelles as non-viral vectors for plasmid DNA: Tumor immunotoxicity in B16F10 melanoma. Biomaterials 2011, 32, 9839–9847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madamsetty, V.S.; Mohammadinejad, R.; Uzieliene, I.; Nabavi, N.; Dehshahri, A.; Garcia-Couce, J.; Tavakol, S.; Moghassemi, S.; Dadashzadeh, A.; Makvandi, P.; et al. Dexamethasone: Insights into pharmacological aspects, therapeutic mechanisms, and delivery systems. ACS Biomater. Sci. Eng. 2022, 8, 1763–1790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Recovery Collaborative Group; Horby, P.; Lim, W.S.; Emberson, J.R.; Mafham, M.; Bell, J.L.; Linsell, L.; Staplin, N.; Brightling, C.; Ustianowski, A.; et al. Dexamethasone in hospitalized patients with Covid-19. N. Engl. J. Med. 2021, 384, 693–704. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Rautio, J.; Kumpulainen, H.; Heimbach, T.; Oliyai, R.; Oh, D.; Järvinen, T.; Savolainen, J. Prodrugs: Design and clinical applications. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2008, 7, 255–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Daull, P.; Paterson, C.A.; Kuppermann, B.D.; Garrigue, J.S. A preliminary evaluation of dexamethasone palmitate emulsion: A novel intravitreal sustained delivery of corticosteroid for treatment of macular edema. J. Ocul. Pharmacol. Ther. 2013, 29, 258–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simon-Vazquez, R.; Tsapis, N.; Lorscheider, M.; Rodriguez, A.; Calleja, P.; Mousnier, L.; de Miguel Villegas, E.; Gonzalez-Fernandez, A.; Fattal, E. Improving dexamethasone drug loading and efficacy in treating arthritis through a lipophilic prodrug entrapped into PLGA-PEG nanoparticles. Drug Deliv. Transl. Res. 2022, 12, 1270–1284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, J.L.; Weiss, R.E. Steroid-induced diabetes: A clinical and molecular approach to understanding and treatment. Diabetes Metab. Res. Rev. 2014, 30, 96–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, D.; Rodrigues, B. Glucocorticoids produce whole body insulin resistance with changes in cardiac metabolism. Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab. 2007, 292, E654–E667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rilo, H.L.; Carroll, P.B.; Zeng, Y.J.; Fontes, P.; Demetris, J.; Ricordi, C. Acceleration of chronic failure of intrahepatic canine islet autografts by a short course of prednisone. Transplantation 1994, 57, 181–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shapiro, A.M.; Ricordi, C.; Hering, B.J.; Auchincloss, H.; Lindblad, R.; Robertson, R.P.; Secchi, A.; Brendel, M.D.; Berney, T.; Brennan, D.C.; et al. International trial of the Edmonton protocol for islet transplantation. N. Engl. J. Med. 2006, 355, 1318–1330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Segura, T.; Hubbell, J.A. Synthesis and in vitro characterization of an ABC triblock copolymer for siRNA delivery. Bioconjug. Chem. 2007, 18, 736–745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buchwald, P.; Bernal, A.; Echeverri, F.; Tamayo-Garcia, A.; Linetsky, E.; Ricordi, C. Fully automated islet cell counter (ICC) for the assessment of islet mass, purity, and size distribution by digital image analysis. Cell Transplant. 2016, 25, 1747–1761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buchwald, P.; Tamayo-Garcia, A.; Manzoli, V.; Tomei, A.A.; Stabler, C.L. Glucose-stimulated insulin release: Parallel perifusion studies of free and hydrogel encapsulated human pancreatic islets. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 2018, 115, 232–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alcazar, O.; Buchwald, P. Concentration-dependency and time profile of insulin secretion: Dynamic perifusion studies with human and murine islets. Front. Endocrinol. 2019, 10, 680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cerritelli, S.; O’Neil, C.P.; Velluto, D.; Fontana, A.; Adrian, M.; Dubochet, J.; Hubbell, J.A. Aggregation behavior of poly(ethylene glycol-bl-propylene sulfide) di- and triblock copolymers in aqueous solution. Langmuir 2009, 25, 11328–11335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bearinger, J.P.; Terrettaz, S.; Michel, R.; Tirelli, N.; Vogel, H.; Textor, M.; Hubbell, J.A. Chemisorbed poly(propylene sulphide)-based copolymers resist biomolecular interactions. Nat. Mater. 2003, 2, 259–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grund, S.; Bauer, M.; Fischer, D. Polymers in drug delivery-state of the art and future trends. Adv. Eng. Mat. 2011, 13, B61–B87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siepmann, J.; Lecomte, F.; Bodmeier, R. Diffusion-controlled drug delivery systems: Calculation of the required composition to achieve desired release profiles. J. Control. Release 1999, 60, 379–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hult, M.; Ortsater, H.; Schuster, G.; Graedler, F.; Beckers, J.; Adamski, J.; Ploner, A.; Jornvall, H.; Bergsten, P.; Oppermann, U. Short-term glucocorticoid treatment increases insulin secretion in islets derived from lean mice through multiple pathways and mechanisms. Mol. Cell. Endocrinol. 2009, 301, 109–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rafacho, A.; Marroqui, L.; Taboga, S.R.; Abrantes, J.L.; Silveira, L.R.; Boschero, A.C.; Carneiro, E.M.; Bosqueiro, J.R.; Nadal, A.; Quesada, I. Glucocorticoids in vivo induce both insulin hypersecretion and enhanced glucose sensitivity of stimulus-secretion coupling in isolated rat islets. Endocrinology 2010, 151, 85–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lund, T.; Fosby, B.; Korsgren, O.; Scholz, H.; Foss, A. Glucocorticoids reduce pro-inflammatory cytokines and tissue factor in vitro and improve function of transplanted human islets in vivo. Transpl. Int. 2008, 21, 669–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chou, D.H.; Bodycombe, N.E.; Carrinski, H.A.; Lewis, T.A.; Clemons, P.A.; Schreiber, S.L.; Wagner, B.K. Small-molecule suppressors of cytokine-induced β-cell apoptosis. ACS Chem. Biol. 2010, 5, 729–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zawalich, W.S.; Tesz, G.J.; Yamazaki, H.; Zawalich, K.C.; Philbrick, W. Dexamethasone suppresses phospholipase C activation and insulin secretion from isolated rat islets. Metabolism 2006, 55, 35–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tijani, O.K.; Moreno-Lopez, M.; Louvet, I.; Acosta-Montalvo, A.; Coddeville, A.; Gmyr, V.; Kerr-Conte, J.; Pattou, F.; Vantyghem, M.C.; Saponaro, C.; et al. Impact of therapeutic doses of prednisolone and other glucocorticoids on insulin secretion from human islets. Ann. Endocrinol. 2025, 86, 101676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dane, K.Y.; Nembrini, C.; Tomei, A.A.; Eby, J.K.; O’Neil, C.P.; Velluto, D.; Swartz, M.A.; Inverardi, L.; Hubbell, J.A. Nano-sized drug-loaded micelles deliver payload to lymph node immune cells and prolong allograft survival. J. Control. Release 2011, 156, 154–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monk, N.J.; Hargreaves, R.E.; Simpson, E.; Dyson, J.P.; Jurcevic, S. Transplant tolerance: Models, concepts and facts. J. Mol. Med. 2006, 84, 295–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, H.S.; Liu, W.; Misra, P.; Tanaka, E.; Zimmer, J.P.; Itty Ipe, B.; Bawendi, M.G.; Frangioni, J.V. Renal clearance of quantum dots. Nat. Biotechnol. 2007, 25, 1165–1170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cybulski, P.; Bravo, M.; Chen, J.J.; Van Zundert, I.; Krzyzowska, S.; Taemaitree, F.; Uji, I.H.; Hofkens, J.; Rocha, S.; Fortuni, B. Nanoparticle accumulation and penetration in 3D tumor models: The effect of size, shape, and surface charge. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2024, 12, 1520078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Drug | Drug/Polymer Initial Ratio (mg/mg) | EE (%), Mean ± SD | DL (wt/wt), Mean ± SD |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dexamethasone (Dexa) | 1:10 | 34.06 ± 8.56 | 0.0346 ± 0.008 |

| Dexamethasone palmitate (DexP) | 1:10 | 58.35 ± 9.69 | 0.058 ± 0.009 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Palummieri, G.; Saadat, S.; Chuang, S.-T.; Buchwald, P.; Velluto, D. Drug-Integrating Amphiphilic Nano-Assemblies: 3. PEG-PPS/Palmitate Nanomicelles for Sustained and Localized Delivery of Dexamethasone in Cell and Tissue Transplantations. Pharmaceutics 2025, 17, 1337. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmaceutics17101337

Palummieri G, Saadat S, Chuang S-T, Buchwald P, Velluto D. Drug-Integrating Amphiphilic Nano-Assemblies: 3. PEG-PPS/Palmitate Nanomicelles for Sustained and Localized Delivery of Dexamethasone in Cell and Tissue Transplantations. Pharmaceutics. 2025; 17(10):1337. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmaceutics17101337

Chicago/Turabian StylePalummieri, Giulio, Saeida Saadat, Sung-Ting Chuang, Peter Buchwald, and Diana Velluto. 2025. "Drug-Integrating Amphiphilic Nano-Assemblies: 3. PEG-PPS/Palmitate Nanomicelles for Sustained and Localized Delivery of Dexamethasone in Cell and Tissue Transplantations" Pharmaceutics 17, no. 10: 1337. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmaceutics17101337

APA StylePalummieri, G., Saadat, S., Chuang, S.-T., Buchwald, P., & Velluto, D. (2025). Drug-Integrating Amphiphilic Nano-Assemblies: 3. PEG-PPS/Palmitate Nanomicelles for Sustained and Localized Delivery of Dexamethasone in Cell and Tissue Transplantations. Pharmaceutics, 17(10), 1337. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmaceutics17101337