Clinical and Immunological Recovery Trajectories in Severe COVID-19 Survivors: A 12-Month Prospective Follow-Up Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

- (i)

- characterize longitudinal changes in lymphocyte subsets, activation markers, NK cells, immunoglobulins, and complement components;

- (ii)

- examine associations between immune recovery and persistent clinical symptoms; and

- (iii)

- explore whether immune trajectories differ according to the initial severity of illness.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Participants

2.2. Follow-Up Schedule and Clinical Data Collection

- A structured interview to assess persistent symptoms (fatigue, dyspnea, exercise intolerance, neurocognitive complaints, musculoskeletal symptoms, and others); participants were asked whether each symptom was new compared with their pre-COVID condition. Only new or worsened symptoms were recorded as post-COVID manifestations according to the WHO clinical case definition (symptoms persisting ≥ 3 months and not explained by alternative diagnoses),

- All participants were asked about immunomodulatory medication use during the 12-month follow-up,

- A targeted clinical evaluation,

- Peripheral blood sampling for immunological analysis.

2.3. Laboratory Assessments

2.4. Missing Data Analysis

2.5. Statistical Analysis

2.6. Ethical Considerations

3. Results

3.1. Study Population and Follow-Up Completion

3.2. Symptom Recovery over Time

3.3. Immune System Recovery

3.3.1. Cellular Immunity

- Activated T cells (CD3+HLA-DR+) declined from 20% at 3 months to 13% at 12 months (p < 0.001).

- CD3+CD8+ T cells decreased significantly by 12 months (572 vs. 632 cells/µL at 3 months, p = 0.020).

- The CD4/CD8 ratio showed a gradual upward trend, suggesting immune homeostasis restoration.

3.3.2. Complement Activation and Immunoglobulin Changes

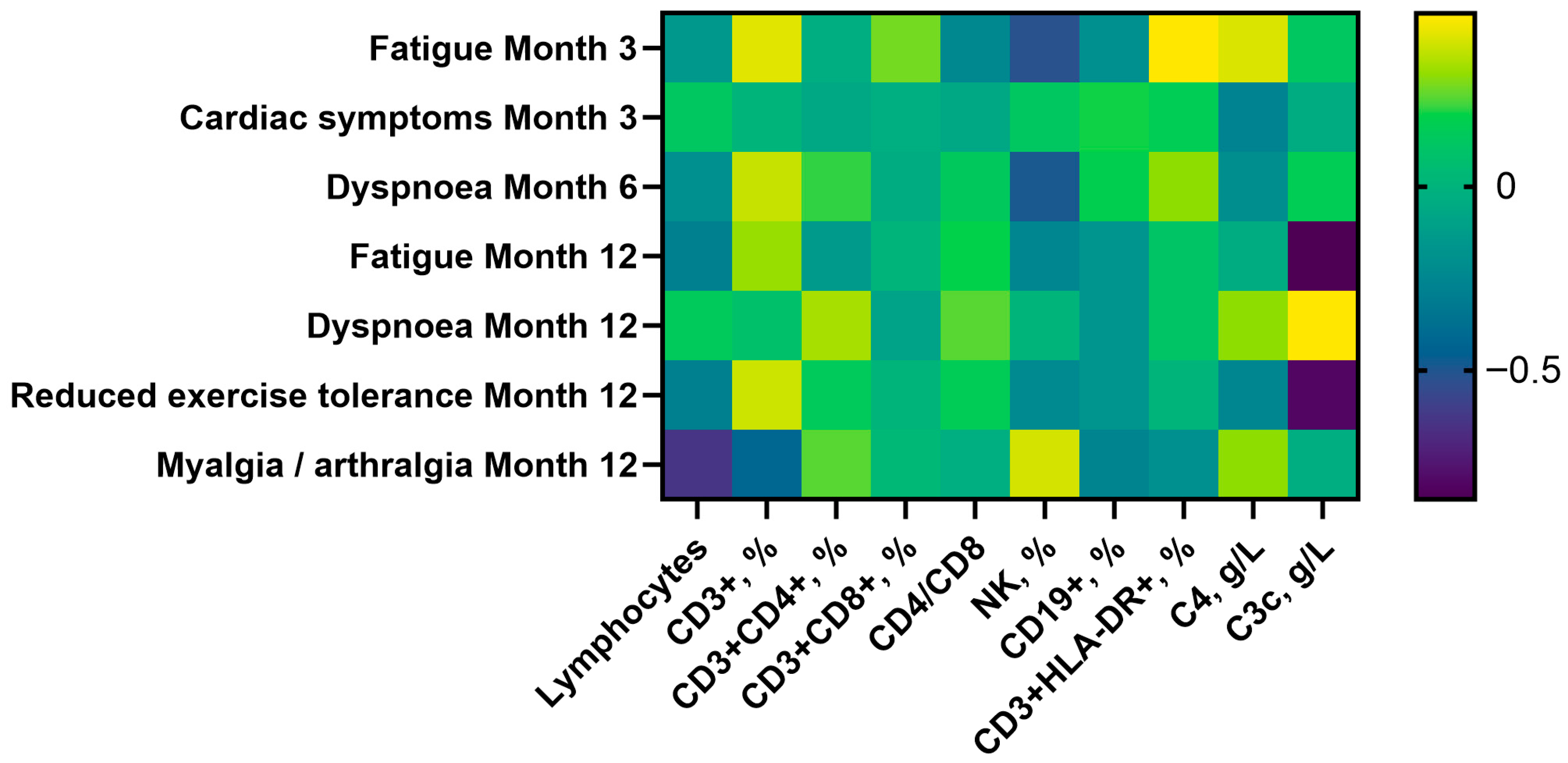

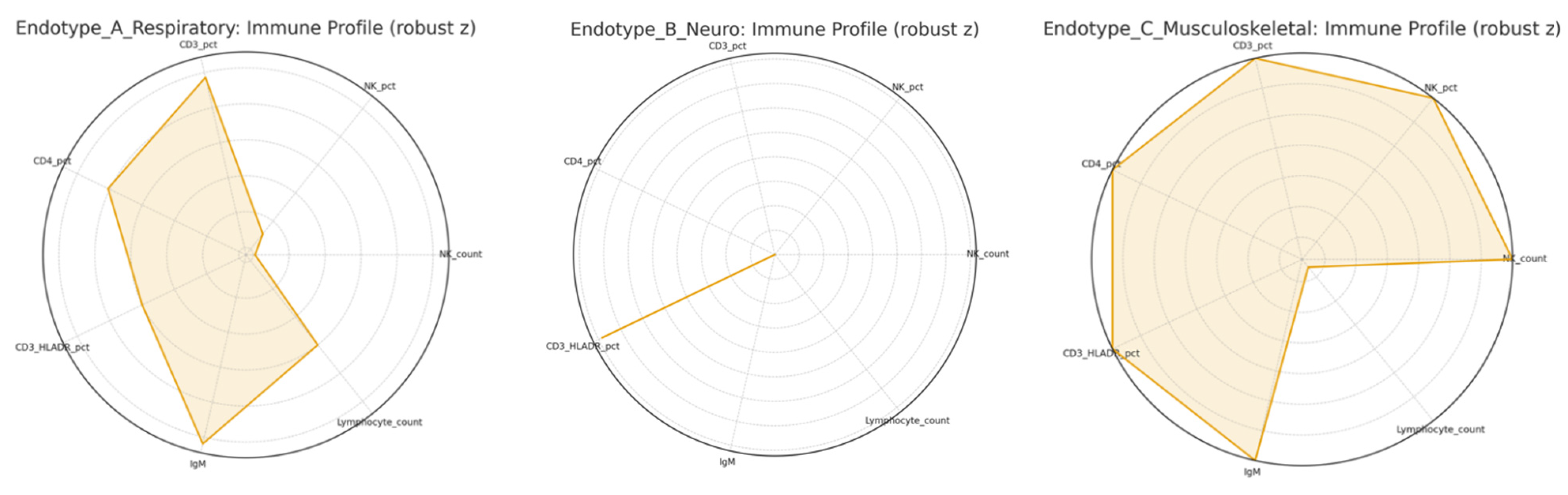

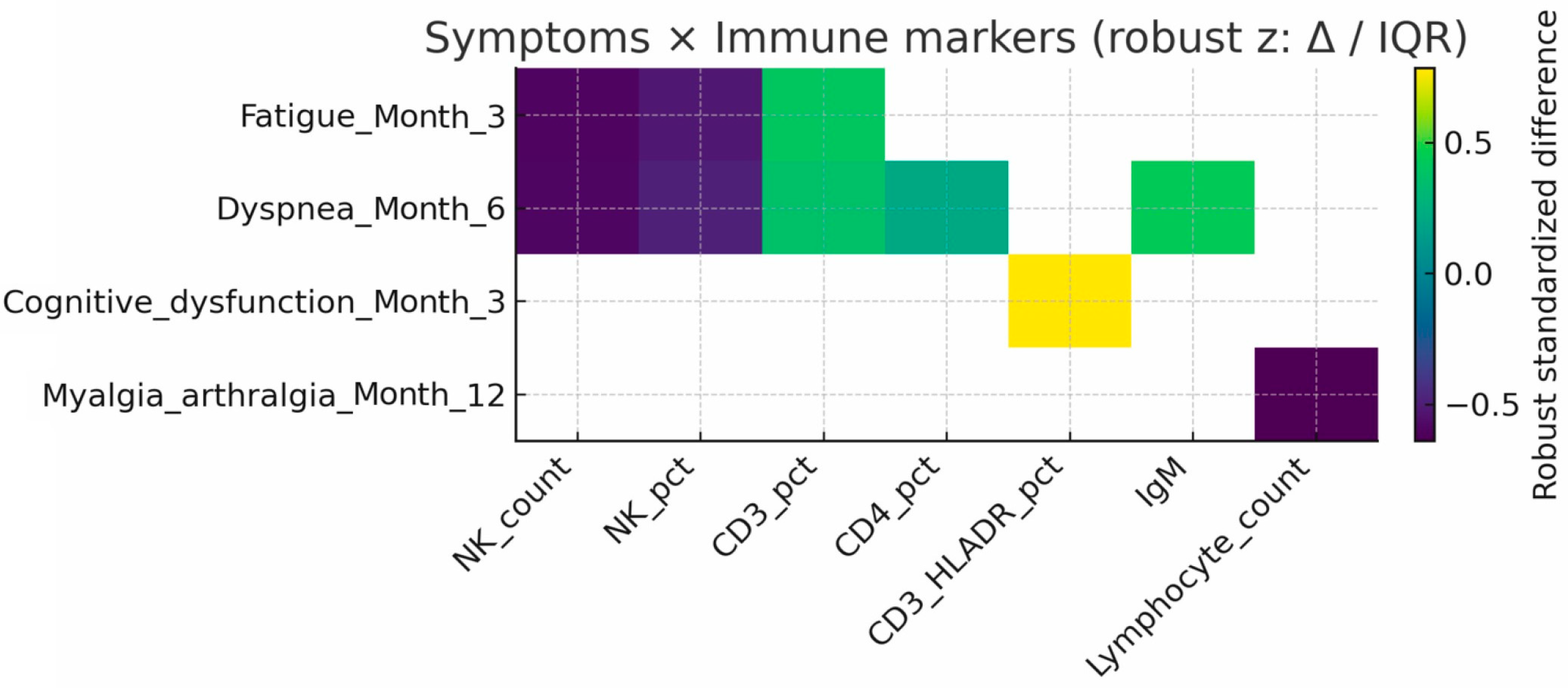

3.4. Clinical-Immunological Correlations

- Fatigue (3 months): linked to lower NK counts (293 vs. 478 cells/µL, p = 0.005) and higher CD3+ T-cell percentages (72% vs. 68%, p = 0.029).

- Dyspnea (6 months): associated with reduced NK counts (240 vs. 426 cells/µL, p = 0.006) and higher CD3+CD4+ T-cell percentages (40% vs. 38%, p = 0.045).

- Myalgia/arthralgia (12 months): associated with lower lymphocyte, CD3+, CD3+CD4+, and CD19+ cell counts.

- Cardiac symptoms (3 months): associated with higher C3c (1.37 vs. 1.20 g/L, p = 0.026).

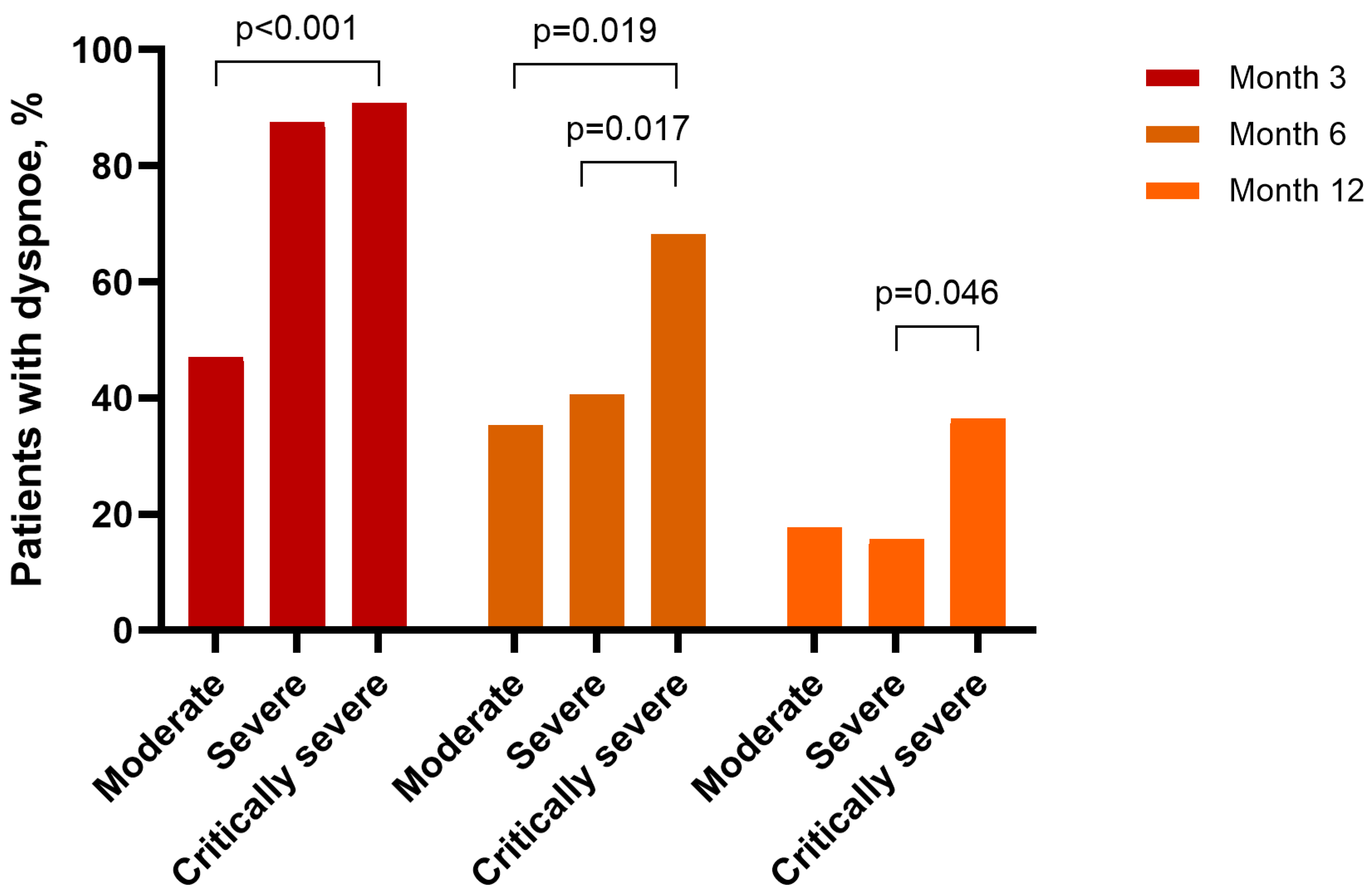

3.5. Influence of Disease Severity

4. Discussion

5. Study Limitations

6. Clinical and Research Implications

7. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Soriano, J.B.; Murthy, S.; Marshall, J.C.; Relan, P.; Diaz, J.V. WHO Clinical Case Definition Working Group on Post-COVID-19 Condition. A Clinical Case Definition of Post-COVID-19 Condition by a Delphi Consensus. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2022, 22, e102–e107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Davis, H.E.; McCorkell, L.; Vogel, J.M.; Topol, E.J. Long COVID: Major Findings, Mechanisms and Recommendations. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2023, 21, 133–146, Erratum in Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2023, 21, 408. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41579-023-00896-0. PMID: 36639608; PMCID: PMC9839201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, H.E.; Assaf, G.S.; McCorkell, L.; Wei, H.; Low, R.J.; Re’em, Y.; Redfield, S.; Austin, J.P.; Akrami, A. Characterizing Long COVID in an International Cohort: 7 Months of Symptoms and Their Impact. eClinicalMedicine 2021, 38, 101019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Lucas, C.; Wong, P.; Klein, J.; Castro, T.B.R.; Silva, J.; Sundaram, M.; Ellingson, M.K.; Mao, T.; Oh, J.E.; Israelow, B.; et al. Longitudinal Analyses Reveal Immunological Misfiring in Severe COVID-19. Nature 2020, 584, 463–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Taeschler, P.; Adamo, S.; Deng, Y.; Cervia, C.; Zurbuchen, Y.; Chevrier, S.; Raeber, M.E.; Hasler, S.; Bächli, E.; Rudiger, A.; et al. T-Cell Recovery and Evidence of Persistent Immune Activation 12 Months After Severe COVID-19. Allergy 2022, 77, 2468–2481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Sekine, T.; Perez-Potti, A.; Rivera-Ballesteros, O.; Strålin, K.; Gorin, J.B.; Olsson, A.; Llewellyn-Lacey, S.; Kamal, H.; Bogdanovic, G.; Muschiol, S.; et al. Robust T Cell Immunity in Convalescent Individuals with Asymptomatic or Mild COVID-19. Cell 2020, 183, 158–168.e14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Huang, C.; Huang, L.; Wang, Y.; Li, X.; Ren, L.; Gu, X.; Kang, L.; Guo, L.; Liu, M.; Zhou, X.; et al. 6-Month Consequences of COVID-19 in Patients Discharged from Hospital: A Cohort Study. Lancet 2023, 401, e21–e33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Huang, L.; Yao, Q.; Gu, X.; Wang, Q.; Ren, L.; Wang, Y.; Hu, P.; Guo, L.; Liu, M.; Xu, J.; et al. 1-Year Outcomes in Hospital Survivors with COVID-19: A Longitudinal Cohort Study. Lancet 2021, 398, 747–758, Erratum in Lancet 2022, 399, 1778. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(22)00795-4. PMID: 34454673; PMCID: PMC8389999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-de-Las-Peñas, C.; Palacios-Ceña, D.; Gómez-Mayordomo, V.; Florencio, L.L.; Cuadrado, M.L.; Plaza-Manzano, G.; Navarro-Santana, M. Prevalence of Post-COVID-19 Symptoms in Hospitalized and Non-Hospitalized COVID-19 Survivors: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Eur. J. Intern. Med. 2021, 92, 55–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Vanichkachorn, G.; Newcomb, R.; Cowl, C.T.; Murad, M.H.; Breeher, L.; Miller, S.; Trenary, M.; Neveau, D.; Higgins, S. Post-COVID-19 Syndrome (Long Haul Syndrome): Description of a Multidisciplinary Clinic at Mayo Clinic and Characteristics of the Initial Patient Cohort. Mayo Clin. Proc. 2021, 96, 1782–1791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Wu, X.; Liu, X.; Zhou, Y.; Yu, H.; Li, R.; Zhan, Q.; Ni, F.; Fang, S.; Lu, Y.; Ding, X.; et al. 3-Month, 6-Month, 9-Month, and 12-Month Respiratory Outcomes in Patients Following COVID-19-Related Hospitalization: A Prospective Study. Lancet Respir. Med. 2021, 9, 747–754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Afzali, B.; Noris, M.; Lambrecht, B.N.; Kemper, C. The State of Complement in COVID-19. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2022, 22, 77–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Mastellos, D.C.; Pires da Silva, B.G.P.; Fonseca, B.A.L.; Fonseca, N.P.; Auxiliadora-Martins, M.; Mastaglio, S.; Ruggeri, A.; Sironi, M.; Radermacher, P.; Chrysanthopoulou, A.; et al. Complement C3 vs C5 Inhibition in Severe COVID-19: Early Clinical Findings Reveal Differential Biological Efficacy. Clin. Immunol. 2020, 220, 108598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Sterlin, D.; Mathian, A.; Miyara, M.; Mohr, A.; Anna, F.; Claër, L.; Quentric, P.; Fadlallah, J.; Devilliers, H.; Ghillani, P.; et al. IgA Dominates the Early Neutralizing Antibody Response to SARS-CoV-2. Sci. Transl. Med. 2021, 13, eabd2223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Isho, B.; Abe, K.T.; Zuo, M.; Jamal, A.J.; Rathod, B.; Wang, J.H.; Li, Z.; Chao, G.; Rojas, O.L.; Bang, Y.M.; et al. Persistence of Serum and Saliva Antibody Responses to SARS-CoV-2 Spike Antigens in COVID-19 Patients. Sci. Immunol. 2020, 5, eabe5511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Sousa, G.F.; Carpes, R.M.; Silva, C.A.O.; Pereira, M.E.P.; Silva, A.C.V.F.; Coelho, V.A.G.S.; Costa, E.P.; Mury, F.B.; Gestinari, R.S.; Souza-Menezes, J.; et al. Immunoglobulin A as a Key Immunological Molecular Signature of Post-COVID-19 Conditions. Viruses 2023, 15, 1545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Sheikh-Mohamed, S.; Isho, B.; Chao, G.Y.C.; Zuo, M.; Cohen, C.; Lustig, Y.; Nahass, G.R.; Salomon-Shulman, R.E.; Blacker, G.; Fazel-Zarandi, M.; et al. Systemic and Mucosal IgA Responses Are Variably Induced in Response to SARS-CoV-2 mRNA Vaccination and Are Associated with Protection Against Subsequent Infection. Mucosal Immunol. 2022, 15, 799–808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- World Health Organization (WHO). Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19): Post COVID-19 Condition. 28 March 2023. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/questions-and-answers/item/coronavirus-disease-(covid-19)-post-covid-19-condition (accessed on 9 December 2025).

- World Health Organization (WHO). Obesity and Overweight. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/obesity-and-overweight (accessed on 9 December 2025).

- World Medical Association. Declaration of Helsinki: Ethical Principles for Medical Research Involving Human Subjects. JAMA 2013, 310, 2191–2194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, L.; Li, X.; Gu, X.; Zhang, H.; Ren, L.; Guo, L.; Liu, M.; Wang, Y.; Cui, D.; Wang, Y.; et al. Health Outcomes in People 2 Years After Surviving Hospitalization with COVID-19: A Longitudinal Cohort Study. Lancet Respir. Med. 2022, 10, 863–876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Karuturi, S. Long COVID-19: A Systematic Review. J. Assoc. Physicians India 2023, 71, 82–94. [Google Scholar]

- Leitner, M.; Pinter, D.; Ropele, S.; Koini, M. Functional Connectivity Changes in Long-Covid Patients with and without Cognitive Impairment. Cortex 2025, 191, 74–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Subramanian, A.; Nirantharakumar, K.; Hughes, S.; Myles, P.; Williams, T.; Gokhale, K.M.; Taverner, T.; Chandan, J.S.; Brown, K.; Simms-Williams, N.; et al. Symptoms and Risk Factors for Long COVID in Non-Hospitalized Adults. Nat. Med. 2022, 28, 1706–1714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Robineau, O.; Hüe, S.; Surenaud, M.; Lemogne, C.; Dorival, C.; Wiernik, E.; Brami, S.; Nicol, J.; de Lamballerie, X.; Blanché, H.; et al. Symptoms and Pathophysiology of Post-Acute Sequelae Following COVID-19 (PASC): A Cohort Study. eBioMedicine 2025, 117, 105792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Bertoletti, A.; Le Bert, N.; Tan, A.T. SARS-CoV-2-Specific T Cells in the Changing Landscape of the COVID-19 Pandemic. Immunity 2022, 55, 1764–1778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yin, K.; Peluso, M.J.; Luo, X.; Thomas, R.; Shin, M.G.; Neidleman, J.; Andrew, A.; Young, K.C.; Ma, T.; Hoh, R.; et al. Long COVID Manifests with T Cell Dysregulation, Inflammation and an Uncoordinated Adaptive Immune Response to SARS-CoV-2. Nat. Immunol. 2024, 25, 218–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Santa Cruz, A.; Mendes-Frias, A.; Azarias-da-Silva, M.; André, S.; Oliveira, A.I.; Pires, O.; Mendes, M.; Oliveira, B.; Braga, M.; Lopes, J.R.; et al. Post-Acute Sequelae of COVID-19 Is Characterized by Diminished Peripheral CD8+β7 Integrin+ T Cells and Anti-SARS-CoV-2 IgA Response. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 1772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Santopaolo, M.; Gregorova, M.; Hamilton, F.; Arnold, D.; Long, A.; Lacey, A.; Oliver, E.; Halliday, A.; Baum, H.; Hamilton, K.; et al. Prolonged T-Cell Activation and Long COVID Symptoms Independently Associate with Severe COVID-19 at 3 Months. eLife 2023, 12, e85009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Krämer, B.; Knoll, R.; Bonaguro, L.; ToVinh, M.; Raabe, J.; Astaburuaga-García, R.; Schulte-Schrepping, J.; Kaiser, K.M.; Rieke, G.J.; Bischoff, J.; et al. Early IFN-α Signatures and Persistent Dysfunction Are Distinguishing Features of NK Cells in Severe COVID-19. Immunity 2021, 54, 2650–2669.e14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maucourant, C.; Filipovic, I.; Ponzetta, A.; Aleman, S.; Cornillet, M.; Hertwig, L.; Strunz, B.; Lentini, A.; Reinius, B.; Brownlie, D.; et al. Natural Killer Cell Immunotypes Related to COVID-19 Disease Severity. Sci. Immunol. 2020, 5, eabd6832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Leem, G.; Cheon, S.; Lee, H.; Choi, S.J.; Jeong, S.; Kim, E.S.; Jeong, H.W.; Jeong, H.; Park, S.H.; Kim, Y.S.; et al. Abnormality in the NK-Cell Population Is Prolonged in Severe COVID-19 Patients. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2021, 148, 996–1006.e18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Tsao, T.; Buck, A.M.; Grimbert, L.; LaFranchi, B.H.; Altamirano Poblano, B.; Fehrman, E.A.; Dalhuisen, T.; Hsue, P.Y.; Kelly, J.D.; Martin, J.N.; et al. Long COVID Is Associated with Lower Percentages of Mature, Cytotoxic NK Cell Phenotypes. J. Clin. Investig. 2024, 135, e188182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Holter, J.C.; Pischke, S.E.; de Boer, E.; Lind, A.; Jenum, S.; Holten, A.R.; Tonby, K.; Barratt-Due, A.; Sokolova, M.; Schjalm, C.; et al. Systemic Complement Activation Is Associated with Respiratory Failure in COVID-19 Hospitalized Patients. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2020, 117, 25018–25025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Lo, M.W.; Kemper, C.; Woodruff, T.M. COVID-19: Complement, Coagulation, and Collateral Damage. J. Immunol. 2020, 205, 1488–1495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cervia-Hasler, C.; Brüningk, S.C.; Hoch, T.; Fan, B.; Muzio, G.; Thompson, R.C.; Ceglarek, L.; Meledin, R.; Westermann, P.; Emmenegger, M.; et al. Persistent Complement Dysregulation with Signs of Thromboinflammation in Active Long Covid. Science 2024, 383, eadg7942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Padoan, A.; Sciacovelli, L.; Basso, D.; Negrini, D.; Zuin, S.; Cosma, C.; Faggian, D.; Matricardi, P.; Plebani, M. IgA-Ab Response to Spike Glycoprotein of SARS-CoV-2 in Patients with COVID-19: A Longitudinal Study. Clin. Chim. Acta 2020, 507, 164–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Pisanic, N.; Antar, A.A.R.; Hetrich, M.K.; Demko, Z.O.; Zhang, X.; Spicer, K.; Kruczynski, K.L.; Detrick, B.; Clarke, W.; Knoll, M.D.; et al. Early, Robust Mucosal Secretory Immunoglobulin A but Not Immunoglobulin G Response to Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 Spike in Oral Fluid Is Associated with Faster Viral Clearance and Coronavirus Disease 2019 Symptom Resolution. J. Infect. Dis. 2025, 231, 121–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Baraniuk, J.N.; Eaton-Fitch, N.; Marshall-Gradisnik, S. Meta-Analysis of Natural Killer Cell Cytotoxicity in Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome. Front. Immunol. 2024, 15, 1440643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eaton-Fitch, N.; du Preez, S.; Cabanas, H.; Staines, D.; Marshall-Gradisnik, S. A Systematic Review of Natural Killer Cells Profile and Cytotoxic Function in Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome. Syst. Rev. 2019, 8, 279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Hickie, I.; Davenport, T.; Wakefield, D.; Vollmer-Conna, U.; Cameron, B.; Vernon, S.D.; Reeves, W.C.; Lloyd, A. Dubbo Infection Outcomes Study Group. Post-Infective and Chronic Fatigue Syndromes Precipitated by Viral and Non-Viral Pathogens: Prospective Cohort Study. BMJ 2006, 333, 575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Sorensen, B.; Streib, J.E.; Strand, M.; Make, B.; Giclas, P.C.; Fleshner, M.; Jones, J.F. Complement Activation in a Model of Chronic Fatigue Syndrome. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2003, 112, 397–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lam, M.H.; Wing, Y.K.; Yu, M.W.; Leung, C.M.; Ma, R.C.; Kong, A.P.; So, W.Y.; Fong, S.Y.; Lam, S.P. Mental Morbidities and Chronic Fatigue in Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Survivors: Long-Term Follow-Up. Arch. Intern. Med. 2009, 169, 2142–2147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Post-COVID-19 Symptom | Month 3 | Month 6 | Month 12 | 3 vs. 6 Months | 3 vs. 12 Months | 6 vs. 12 Months |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fatigue | 66 (70.97) | 37 (39.78) | 23 (24.73) | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.001 |

| Dyspnoea | 76 (81.72) | 49 (52.69) | 24 (25.81) | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Reduced exercise tolerance | 66 (70.97) | 47 (50.54) | 23 (24.73) | 0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Myalgia/arthralgia | 19 (20.43) | 12 (12.90) | 14 (15.05) | 0.092 | 0.424 | 0.824 |

| Cardiac symptoms | 11 (11.83) | 2 (2.15) | 3 (3.23) | 0.004 | 0.057 | 1.000 |

| Insomnia/anxiety | 11 (11.83) | 9 (9.68) | 9 (9.68) | 0.791 | 0.815 | 1.000 |

| Cognitive dysfunction/memory impairment | 9 (9.68) | 10 (10.75) | 7 (7.53) | 1.000 | 0.754 | 0.453 |

| Miscellaneous | 33 (35.48) | 21 (22.58) | 15 (16.13) | 0.043 | 0.002 | 0.180 |

| Parameter | N | Absolute Number (Median, IQR), Cells/mm3 | Percentage (Median, IQR) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Month 3 | |||

| Lymphocytes | 93 | 2079(1636–2788) | 36 (30–45) a |

| CD3+ | 88 | 1462(1145–2171.50) a | 72 (68–77.75) a,b |

| CD3+CD4+ | 93 | 818 (643–1082.50) | 39 (33–47) |

| CD3+CD8+ | 93 | 632 (389.5–984.50) b | 31 (21–39.5) a,b |

| CD4/CD8 | 92 | 1.2 (0.85–2.20) | |

| NK | 93 | 325 (194.50–506.50) | 16 (10–21.5) |

| CD19+ | 93 | 184 (135–255.50) | 8 (6–11) |

| CD3+HLA-DR+ | 88 | 413 (242.75–689.25) a,b | 20 (14–26.75) a,b |

| Month 6 | |||

| Lymphocytes | 93 | 2014(1682.50–2518) | 34 (27–42) a |

| CD3+ | 92 | 1438(1090.75–1884.50) a | 71 (65–75.75) a |

| CD3+CD4+ | 92 | 791.50(598.25–1029.25) | 39.50 (34–43.50) |

| CD3+CD8+ | 93 | 619 (430–928.50) c | 31 (21–40) a,c |

| CD4/CD8 | 93 | 1.30 (0.95–2.30) | |

| NK | 93 | 320 (184–499) | 17 (11–23.25) |

| CD19+ | 93 | 172 (124.50–247.50) | 9.67 (6.70–12) |

| CD3+HLA-DR+ | 92 | 337.50 (192–530) a,c | 16 (12–22) a,c |

| Month 12 | |||

| Lymphocytes | 85 | 2016(1565–2 530.5) | 34.80 (29–42) |

| CD3+ | 84 | 1415.5(1025.75–1926) | 72 (65–78) b |

| CD3+CD4+ | 85 | 778 (623–1054.50) | 40 (35.5–46) |

| CD3+CD8+ | 85 | 572 (405–891) b,c | 29 (22–39) b,c |

| CD4/CD8 | 85 | 1.26 (0.92–2.25) | |

| NK | 85 | 321 (174.50–543) | 15 (10.65–23.45) |

| CD19+ | 85 | 177 (131.50–248.50) | 9 (6.25–12) |

| CD3+HLA-DR+ | 82 | 285 (162.25–456) b,c | 13 (9.98–20) b,c |

| Parameter | Month 3 | Month 6 | Month 12 |

|---|---|---|---|

| C4, g/L | 0.25 (0.22–0.29) a | 0.26 (0.19–0.29) a | 0.24 (0.20–0.30) |

| C3c, g/L | 1.23 (1.10–1.39) a,b | 1.30 (1.05–1.39) a,c | 1.35 (1.17–1.51) b,c |

| IgA, g/L | 2.06 (1.53–2.67) a,b | 2.42 (1.81–3.74) a | 2.72 (1.82–3.35) b |

| IgG, g/L | 11.14 (9.54–12.39) | 11.16 (9.98–12.94) | 11.72 (10.11–12.49) |

| IgM, g/L | 0.92 (0.61–1.35) | 0.77 (0.47–1.34) | 0.69 (0.44–1.37) |

| IgE, g/L | 20.50 (12.50–52.80) | 21.90 (13.80–112.60) | 22.10 (10.05–167.90) |

| Parameter | Moderate COVID-19 | Severe COVID-19 | Critically Severe COVID-19 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Month 3 | |||

| C4, g/L | 0.28 (0.22–0.29) | 0.25 (0.20–0.28) | 0.25 (0.22–0.32) |

| C3c, g/L | 1.26 (1.13–1.46) | 1.29 (1.12–1.40) | 1.20 (1.08–1.39) |

| IgA, g/L | 1.61 (1.29–2.33) | 2.37 (1.45–3.02) | 2.07 (1.68–2.52) |

| IgG, g/L | 10.67 (9.51–12.27) | 10.27 (9.27–11.49) * | 11.67 (10.07–12.85) * |

| IgM, g/L | 0.96 (0.67–1.35) | 0.75 (0.44–1.24) * | 1.01 (0.73–1.46) * |

| IgE, g/L | 14.40 (8.08–28.25) | 21.00 (12.50–86.60) | 32.50 (13.95–51.58) |

| Month 6 | |||

| C4, g/L | 0.24 (0.20–0.31) | 0.27 (0.20–0.30) | 0.26 (0.18–0.29) |

| C3c, g/L | 1.24 (0.86–1.38) | 1.34 (1.26–1.52) | 1.25 (1.04–1.38) |

| IgA, g/L | 2.33 (1.54–4.22) | 2.37 (1.42–3.54) | 2.57 (2.18–3.71) |

| IgG, g/L | 11.26 (10.30–12.55) | 10.71 (9.70–13.40) | 11.50 (9.95–13.06) |

| IgM, g/L | 0.93 (0.46–1.59) | 0.60 (0.30–0.78) * | 0.96 (0.52–1.77) * |

| IgE, g/L | 18.70 (8.40–193.73) | 48.85 (17.08–213.23) | 21.90 (10.60–86.85) |

| Month 12 | |||

| C4, g/L | 0.26 (0.24–0.31) | 0.25 (0.17–0.31) | 0.24 (0.19–0.33) |

| C3c, g/L | 1.38 (1.18–1.47) | 1.47 (1.06–1.59) | 1.30 (1.17–1.53) |

| IgA, g/L | 2.21 (1.77–3.65) | 3.20 (1.82–4.37) | 2.58 (1.80–3.23) |

| IgG, g/L | 11.46 (10.81–12.31) | 11.86 (10.05–12.24) | 11.67 (9.15–13.86) |

| IgM, g/L | 0.54 (0.37–1.19) | 0.45 (0.40–1.13) * | 0.92 (0.66–2.62) * |

| IgE, g/L | 33.65 (18.15–186.60) | 52.10 (14.18–431.90) | 14.80 (6.60–58.50) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Strumiliene, E.; Malinauskiene, L.; Urboniene, J.; Jurgauskienė, L.; Zablockienė, B.; Jancoriene, L. Clinical and Immunological Recovery Trajectories in Severe COVID-19 Survivors: A 12-Month Prospective Follow-Up Study. Viruses 2025, 17, 1610. https://doi.org/10.3390/v17121610

Strumiliene E, Malinauskiene L, Urboniene J, Jurgauskienė L, Zablockienė B, Jancoriene L. Clinical and Immunological Recovery Trajectories in Severe COVID-19 Survivors: A 12-Month Prospective Follow-Up Study. Viruses. 2025; 17(12):1610. https://doi.org/10.3390/v17121610

Chicago/Turabian StyleStrumiliene, Edita, Laura Malinauskiene, Jurgita Urboniene, Laimutė Jurgauskienė, Birutė Zablockienė, and Ligita Jancoriene. 2025. "Clinical and Immunological Recovery Trajectories in Severe COVID-19 Survivors: A 12-Month Prospective Follow-Up Study" Viruses 17, no. 12: 1610. https://doi.org/10.3390/v17121610

APA StyleStrumiliene, E., Malinauskiene, L., Urboniene, J., Jurgauskienė, L., Zablockienė, B., & Jancoriene, L. (2025). Clinical and Immunological Recovery Trajectories in Severe COVID-19 Survivors: A 12-Month Prospective Follow-Up Study. Viruses, 17(12), 1610. https://doi.org/10.3390/v17121610